Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs European Union .

essay / Andrea Pavón-Guinea [English version].

-

Introduction

The combination of terrorist attacks on European soil, the rise of the Islamic State, the Syrian civil war and the refugee crisis have highlighted the importance of intercultural dialogue between the European Union and the Islamic world. In this context of asymmetric warfare and non-traditional security challenges, the European Union is focusing its resources on soft power-based civil society initiatives that can contribute to the prevention of radicalization. Through the creation of the Anna Lindh Foundation for Intercultural development , the European Union has a unique instrument to bring civil societies on both shores of the Mediterranean closer together and contribute to the improvement of Euro-Mediterranean relations.

-

Euro-Mediterranean relations and intercultural dialogue

Relations between the European Union and the Southern Mediterranean began[1] to be formally regulated with the creation of the Barcelona Process in 1995[2].

The Barcelona Declaration would give rise to the creation of the association Euro-Mediterranean; a forum for multilateral relations which, 'based on a spirit of association', aims to turn the Mediterranean basin into a 'area of dialogue, exchange and cooperation guaranteeing peace, stability and prosperity'. The Barcelona Process would thus bring to mind one of the founding principles of the European Union, that of achieving common objectives through a spirit of co-responsibility (Suzan, 2002). The Declaration pursues three fundamental objectives: firstly, the creation of a common area of peace and stability through the reinforcement of security and political dialogue (this would be the so-called 'political basket'); secondly, the construction of a zone of shared prosperity through the economic and financial association ('economic and financial basket'); and, thirdly, the promotion of understanding between cultures through civil society networks: the so-called intercultural dialogue ('social, cultural and human affairs' basket).

More than twenty years after the Declaration, the claims of today's politics in the Southern Mediterranean underline the importance of development intercultural dialogue for European security. Although European politicians rejected Huntington's thesis of the clash of civilizations when it was first articulated, it would nevertheless become a scenario to be considered after the September 11 attacks: a scenario, however, that could be avoided through cooperation in the 'third basket' of the Euro-Mediterranean association , i.e. through enhanced dialogue and cultural cooperation (Gillespie, 2004).

-

Fighting radicalization through intercultural dialogue: the Anna Lindh Foundation

Thus, emphasizing that dialogue between cultures, civilizations and religions throughout the Euro-Mediterranean region is more necessary than ever for promote mutual understanding, the Euro-Mediterranean partners agreed during the fifth Euro-Mediterranean Foreign Ministers' meeting lecture in Valencia in 2002 to establish a foundation whose goal would be the development of intercultural dialogue. Thus was born the Anna Lindh Foundation for the Dialogue between Cultures which, based in Alexandria, would start operating in 2005.

It should be noted that Anna Lindh is unique in its representation and configuration, as it brings together all Euro-Mediterranean partners in the promotion of intercultural dialogue, which is its only goal. To this end, it relies on the coordination of a regional network of more than 4,000 civil society organizations, both European and Mediterranean.

Although it has been in operation for more than ten years now, its work is currently focused on development intercultural dialogue in order to prevent radicalization. This emphasis has been continuously highlighted in recent years, for example at the Anna Lindh Foundation's Mediterranean Forum in Malta in October 2016, its mandate on intercultural dialogue contained in the new European Neighborhood Policy (18.11.2015) and in High Representative Mogherini's strategy for the promotion of culture at International Office.

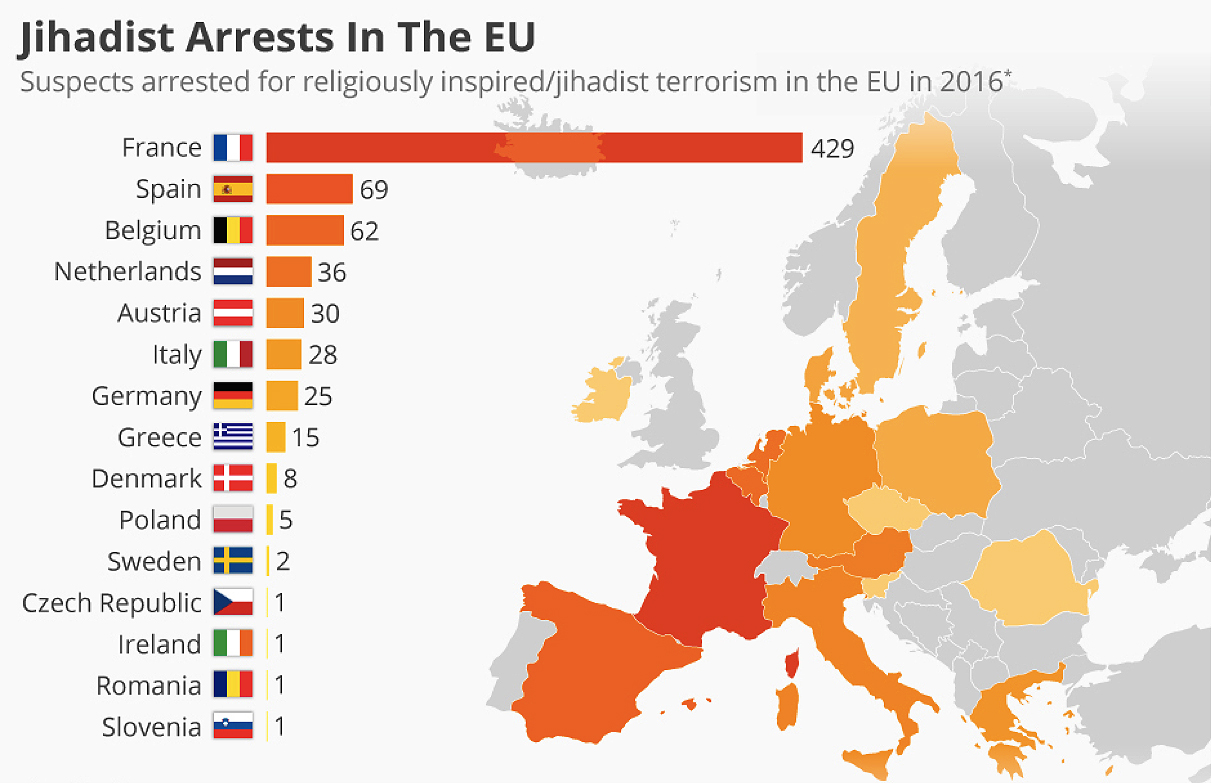

However, it has been the recent terrorist attacks in Europe that have highlighted the urgent need to address the phenomenon of radicalization[3], which can ultimately written request lead to violent extremism and terrorism. In this sense, the prevention of radicalization[4] is a piece core topic in the fight against terrorism, as has been highlighted by the diary European Security in 2015[5]. This is so because most of the terrorists suspected of attacks on European soil are European citizens, born and raised in EU member states, where they have undergone radicalization processes that would culminate in acts of terrorist violence. This fact evidences 'the transnational dimension of Islamist terrorism' (Kaunert and Léonard, 2011: 287), as well as the changing nature of the threat, whose drivers are different and more complex than previous radicalization processes: 'Today's radicalization has different foundations, operates on the basis of different recruitment and communication techniques and is marked by globalized and mobile targets inside and outside Europe, growing in diverse urban contexts'[6]. The following map sample the issue of arrests for suspected jihadist terrorism in Europe in 2016.

|

source: Europol (2016) |

Consequently, the Anna Lindh Foundation can be understood as an alternative and non-confrontational response to the speech of the clash of civilizations and the US-led war on terror (Malmvig, 2007). Its main goal which is to create 'a space of prosperity, coexistence and peace' by 'restoring confidence in dialogue and reducing stereotypes' is based on the importance given by the European Union to development intercultural dialogue between civilizations as a crucial element of any political and strategic program aimed at neighboring Mediterranean countries (Rosenthal, 2007). In other words, the creation of a area of dialogue, cooperation and exchange in the southern Mediterranean is a priority core topic of the European Union's foreign policy. Furthermore, with the creation of the Anna Lindh Foundation, the European Union is recognizing that for the Euro-Mediterranean association to work, dialogue between civil society organizations, and not only between political elites, is essential.

Thus, Anna Lindh, as an organization based on network of civil society networks, becomes a crucial instrument to address the prevention of radicalization. Along these lines, the group of work of the United Nations counter-terrorism implementation[7] has argued that the State alone does not have the necessary resources to combat terrorist radicalization, and therefore needs to cooperate with partners of a different nature to carry out this task. The involvement of civil society and local communities would thus serve to increase trust and social cohesion, even becoming a means of reaching out to certain segments of society with which governments would find it difficult to interact. The nature of local actors, as highlighted by the European Union through the creation of the Anna Lindh Foundation, would be the most successful in preventing and detecting radicalization in both the short and long term deadline[8].

Conclusion

In this way, intercultural dialogue constitutes a tool to address the phenomenon of radicalization in the Southern Mediterranean region, where the legacies of a colonial past demand that 'more credible interlocutors be found among non-governmental organizations' (Riordan, 2005: 182). With the goal of preventing terrorist radicalization inside and outside Europe, and assuming that practices based on dialogue and mutuality can offer a suitable framework for the development and improvement of Euro-Mediterranean relations, the European Union should move towards real partnerships aimed at building trust between people and reject any unilateral action program that involves a reproduction of the speech of the clash of civilizations (Amirah and Behr, 2013: 5).

[1] Prior to the Barcelona Declaration, an attempt was made to regulate Euro-Mediterranean cooperation through the Euro-Arab Dialogue (1973-1989); however, although conceived as a forum for dialogue between the then European Economic Community and the Arab League, the tensions of the Gulf War would end up frustrating its work (Khader, 2015).

[2] The association Euro-Mediterranean would be complemented by the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP) in 2004. Based on the European enlargement policy, its underlying logic is the same: "To try to export the norms and values of the European Union to its neighbors" (Gsthöl, 2016: 3). In response to the conflicts in the Southern Mediterranean regions, the rise of extremism and terrorism and the refugee crisis in Europe, the ENP has undergone two major revisions, one in 2011 and the other in 2015, outlining a more differentiated approach among ENP countries to achieve further stabilization of the area. The ENP is based on differential bilateralism (Del Sarto and Schumacher, 2005) and abandons the prevalence of the multilateral and regional principle inherent to the Barcelona Process.

[3] Although several types of political extremism can be differentiated, this grade focuses on Islamist extremism and jihadist terrorism, as it is Sunni extremism that has been manager of the largest issue of terrorist attacks in the world (Schmid, 2013). It should also be noted in this regard that there is still no universally valid definition of the concept of 'radicalization' (Veldhuis and Staun 2009).

[4] Since 2004, the term 'radicalization' has become central to terrorism studies and counter-terrorism policy-making in order to analyze 'homegrown' Islamist political violence (Kundnani, 2012).

[5] The European diary on Security, COM (2015) 185 of 28 April 2015.

[6] The prevention of radicalization leading to violent extremism, COM (2016) 379 of 14 June 2016.

[7] First Report of the Working Group on Radicalization and Extremism that Lead to Terrorism: Inventory of State Programs (2006)

[8] The prevention of radicalization leading to violent extremism, COM (2016) 379 of 14 June 2016.

Bibliography

Amirah, H. and Behr, T. (2013) "The Missing Spring in the EU's Mediterranean Policies", Policy Paper No 70. Notre Europe - Jacques Delors Institute, February, 2013.

Council of the European Union (2002) "Presidency Conclusions for the Vth Euro-Mediterranean Conference of Foreign Ministers" (Valencia 22-23 April 2002), 8254/02 (Presse 112)

Del Sarto, R. A. and Schumacher, T. (2005): "From EMP to ENP: What's at Stake with the European Neighborhood Policy towards the Southern Mediterranean?", European Foreign Affairs Review, 10: 17-38.

European Union (2016) "Towards an EU Strategy for International Cultural Relations, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council" (https://ec.europa.eu/culture/policies/strategic-framework/strategy-international-cultural-relations_en).

European Commission. "Barcelona Declaration and Euro-Mediterranean Partnership", 1995.

Gillespie, R. (2004) "Reshaping the diary? The International Politics of the Barcelona Process in the Aftermath of September 11", in Jünemann, Annette Euro-Mediterranean Relations after September 11, London: Frank Cass: 20-35.

Gstöhl, S. (2016): The European Neighborhood Policy in a Comparative Perspective: Models, Challenges, Lessons (Abingdon: Routledge).

Kaunert, C. and Léonard, S. (2011) "EU Counterterrorism and the European Neighborhood Policy: An Appraisal of the Southern Dimension", Terrorism and Political Violence, 23: 286-309.

Khader, B. (2015): Europe and the Arab world (Icaria, Barcelona).

Kundnani, A. (2012) "Radicalization: The Journey of a Concept", Race & Class, 54 (2): 3-25.

Malmvig, H. (2007): "Security Through Intercultural Dialogue? Implications of the Securitization of Euro-Mediterranean Dialogue between Cultures". Conceptualizing Cultural and Social Dialogue in the Euro-Mediterranean Area. London/New York: Routledge: 71-87.

Riordan, S. (2005): "Dialogue-Based Public Diplomacy: A New Foreign Policy Paradigm?", in Melissen, Jan, The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations, Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan: 180-193.

Rosenthal, G. (2007): "Preface: The Importance of Conceptualizing Cultural and Social Co-operation in the Euro-Mediterranean Area". Conceptualizing Cultural and Social Dialogue in the Euro-Mediterranean Area. London/New York: Routledge: 1-3.

Schmid, A. (2013) "Radicalization, De-Radicalization, Counter-Radicalization: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review", ICCT Research Paper, March 2013.

Suzan, B. (2002): "The Barcelona Process and the European Approach to Fighting Terrorism." Brookings Institute [online] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-barcelona-process-and-the-european-approach-to-fighting-terrorism/ [accessed 14 August 2017].

Veldhuis, T. and Staun, J. (2009) Islamist Radicalisation: A Root Cause Model (The Hague: Clingendael).

I. Introduction

On 31 March 2016, the High Representative of the EU, Federica Mogherini, presented the new cultural diplomacy platform, which goal is to enhance visibility and understanding of the Union through intercultural dialogue. The fact that all influential actors are committed to this platform (from a top-down, bottom-up perspective), means that we need to reconsider three EU factors: (1) the context in which it operates; (2) the domestic constraints it has to address, and (3) the foreign policy it aspires to. However, the EU wants to give a single cultural image, with a single voice that is consistent with its policies; That is why, first and foremost, the EU must uphold its motto 'unity in diversity'. This motto signifies the integration of national cultures into other countries, without this integration endangering the different national identities of the member states. Consequently, in its status as an international actor and regional organisation, the EU is lacking in intercultural dialogue and negotiation between identities (European External Action Service, 2017). For this reason, it must strive both in one and in the other (intercultural dialogue and the negotiation between identities) to face threats to European security such as terrorism, cyber-insecurity, energy insecurity or identity ambiguity.

The goal The aim of this analysis is, on the one hand, to understand the importance of culture as an instrument of soft power, and on the other hand, to reflect on the influence of culture as the theoretical foundation of the new European cultural platform.

II. Unity in diversity through the New Cultural Diplomacy Platform

If the European Union aspires to be a liberal order based on cooperation, then to what extent can the EU be globally influential? What is undeniable is that it lacks a single voice and a coherent common foreign policy.

The fact that the EU lacks a single voice is result of the course of integration throughout history, an integration that has been based more on diversity and not so much on equality. On the other hand, the assertion about the incoherence of the common foreign policy makes reference letter to all those cases in which, in the face of a coordination problem, what was agreed in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty takes precedence (Banús, 2015: 103-105 and Art. 6, TFEU): the competences may be of the member states, of the EU or they may be shared competences

As a result of the acceleration of globalisation, the increase in non-traditional security threats (international terrorism, energy vulnerability, irregular migratory flows, cyber threats or climate change) the idea of a common foreign policy between member states and the EU is challenged. Such threats demand not only a new paradigm of security, but also a new paradigm of coexistence. This paradigm shift would allow the EU to have a greater capacity to reduce radicalisation and to direct coexistence towards the needs of civil societies (see European Commission, 2016). By way of illustration of the new paradigm, we can name the promotion of narratives of a shared cultural heritage that financial aid to the regional integration process. However, at the same time that initiatives such as the above are implemented, scepticism towards immigrants is growing and narratives contrary to the EU narrative projected by the EU are being promoted. These institutional and structural constraints – diversity and shared competences – reflect the dynamics of the cultural landscape and their unintended consequences within the EU. They also give a glimpse of the project European identity as a process of integration (unity in diversity) and European identity as a single voice. Therefore, the EU, as an international actor and regional organisation, based on unity in diversity, has a need to establish an intercultural dialogue and a negotiation of shared identities from within its organisation (EEAS, 2017). This would serve not only to establish favourable conditions for Brussels' policies, but also as an instrument or means for the EU to counter non-traditional and external threats, such as terrorism, populist narratives, cyber threats, energy insecurity and identity ambiguity.

Regarding the difficulty in distinguishing internal constraints and external threats, Federica Mogherini established the New Cultural Diplomacy Platform (NPC) in 2016.

With the goal to clarify the terminology Previously used, 'cultural diplomacy' is understood as a 'balance of power' according to the approach realistic and as a "reflective balance" from a approach (Triandafyllidou & Szucs, 2017). On the one hand, the approach realist understands cultural diplomacy as a subject of dialogue that serves to advance and protect national interests abroad (e.g. joint European cultural events or bilateral programmes, such as film festivals, support for the strengthening of Tunisia's cultural sector, the creation of European cultural houses, the Culture and Creativity, Communication and Culture programme for the development in the Southern Mediterranean region, and the NPC). On the other hand, the approach Conceptually, more reflectively, he understands cultural diplomacy as a policy in itself. The potential of cultural synergies is fostered for a development social and economic sustainability through individuals (e.g. cultural exchanges such as Erasmus Plus, the Instrument for Promoting and Developing Countries). development and Cooperation and its subprogrammes, the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR), the ENI Cross Border Cooperation and the Civil Society Facility). The application of cultural diplomacy to the EU seeks to have global visibility and influence, and on the other hand, seeks to promote economic growth and social cohesion through civil societies (Trobbiani, 2017: 3-5).

Despite being funded by the Partnership Instrument (PI), which has as its goal to promote visibility and understanding of the EU, the NPC is a balance between the approach realistic and the approach (European Commission, 2016b). Consequently, it is a resilience strategy that responds to a new reality (resilience is understood in terms of inclusiveness, prosperity and security of society). In this reality, non-traditional security threats have emerged and in which there has been a change in the position of citizens, who have gone from being independent observers, to being active participants demanding a constructive dialogue involving all stakeholders: national governments, international organizations and civil societies (Higgot, 2017:6-8 and EU, 2016).

The 2016 Global Strategy seeks pluralism, coexistence and respect by "deepening the work In the Education, culture and youth" (EU, 2016). In other words, the platform invests in Structures creative organizations, such as think tanks, cultural institutes, or local artists, to preserve a cultural identity, advance economic prosperity, and enhance soft power.

By seeking global understanding and visibility, we see how the EU's interest in international cultural relations (ICR) and cultural diplomacy (CD) has grown. This, in turn, reflects the EU's internal need for a single voice and a common foreign policy. This effort demonstrates the fundamental role of culture in soft power, thus creating a connection between culture and external power. Perhaps the most appropriate question is: to what extent can Mogherini's NCP turn culture into a tool soft power? And are the strategies – ICR and NCP – a communication and a model effective coordination in the face of internal and external security threats, or will it inevitably undermine their narrative of unity in diversity?

III. Culture and Soft Power

The change in the concept of security requires a revisit of the concept of soft power. In this case, cultural diplomacy must be understood in terms of soft power, and soft power must be understood in terms of attractiveness and influence. Soft power, of agreement with Joseph Nye's notion of persuasion, it arises from "intangible resources of power": "such as culture, ideology and institutions" (Nye, 1992:150-170).

The EU as a product of cultural dialogues is a civil power, a normative power and a soft power. The EU's power of persuasion depends on its legitimacy and credibility in its institutions (EU, 2016a and Michalski, 2005:124-141). For this reason, the coherence between the identity that the EU wishes to show and the practices it will follow is fundamental for the projection of itself as a credible international actor. This coherence will be necessary if the EU is to meet its goal to "reinforce unity in diversity". Otherwise, their liberal values would be contradicted and populist prejudices against the EU would be solidified. Thus, domestic legitimacy and credibility as sources of soft power ultimately depend on the written request of the consistency between the EU's narrative identity and the democratic values reflected in its practices (EU, 2016).

Cultural diplomacy responds to incoherence by requiring reflection, on the one hand, and improving that identity, on the other. For example, optimising Europe's image through the European Neighbourhood Instrument communication programme and association (ENPI) help promote specific geopolitical interests, creating more durable conditions for cooperation with countries such as Algeria, Libya and Syria to the south; and Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine to the east. This is relevant in relation to what Nye coined as "co-optive power": "the ability of a country to manage a status so that other countries develop certain preferences or define their interests in the agreement with their own" (Nye, 1990:168). Soft power applied to culture can work indirectly or directly. It works indirectly when it is independent of government control (e.g., popular culture) and directly through cultural diplomacy (e.g., the NCP). Foreign policy actors can act as defenders of domestic culture, both consciously (e.g., politicians) and unconsciously (e.g., local artists). In doing so, they serve as agents for other countries or channels of soft power.

IV. Culture and foreign policy

Considering soft power as an emergence of culture, values, and national policies, we can say that culture is both a foundation and a foundation. resource of foreign policy (Liland, 1993:8). Foreign policy, in turn, operates within the framework of any society interacting at the international level. Therefore, there is a need for a European cultural context capable of influencing the world (such as the difference in the accession negotiations between Croatia and Turkey and the attractiveness of economic integration or the ability to adjust human rights policies). Culture, in turn, is a resource, as the exchange empowers the EU. This new capacity of the EU allows it to become acquainted with new attitudes, sentiments and popular images that are capable of influencing foreign policy, domestic policy and social life. (Liland, 1993:9-14 and Walt, 1998). Another noteworthy function of culture is the dissemination of information and its ability to obtain favorable opinions in the foreign nation (Liland, 1993:12-13).

Cultural diplomacy is therefore at the forefront of European foreign policy; On the other hand, this does not mean that the use of culture can replace traditional foreign policy objectives – geography, power, security, politics and economics – but that the use of culture serves to support and legitimize them. In other words, culture is not the main agent in the foreign policy process, but is the foundation that reinforces, contradicts, or explains its content – thus, Wilson's idealism in the 1920s can be linked to a domestic culture of "manifest destiny" (Liland, 1993 and Kim, 2011:6).

V. Conclusions

The purpose of this article has been to highlight the importance of culture in relation to soft power and foreign policy, as a theoretical foundation to understand the logic of the new EU Cultural Diplomacy platform. Identifying the role of culture as a fundamental part of social cohesion within the EU, we can conclude that culture has made the EU a global actor with more capacity for influence. Culture, likewise, has been identified as source and as an instrument of foreign policy. But the sources of soft power—culture, political values, and foreign policy—depend on three factors: (1) a favorable context; (2) credibility in values and internship, and (3) the perception of legitimacy and moral authority (see Nye, 2006). The EU must first legitimise itself as a coherent actor with moral authority, in order to be able to deal effectively with its existential crisis (European Union, 2016a:9 and Tuomioja, 2009).

To do so, the EU must overcome its institutional and structural limits by collectively confronting its non-traditional external external security threats. This requires a strategy of resistance in which the EU is not identified as a threat to national identity, but as a cultural, economic and legislative entity.

In this article various topics related to culture, soft power, the EU's foreign policy and its internal dynamics were discussed; However, the impact of a "uniform cultural system" and how foreign policy can influence a society's culture has not been analysed in depth. Culture is not an end in itself, nor are intercultural dialogues and the development of cultural diplomacy.

The Union should avoid the risk of evolving towards a dehumanising bureaucratic structure favouring a standard culture to counter its internal constraints and non-traditional external security threats. According to Vaclav Havel, the EU can avoid this phenomenon by supporting cultural institutions that work for plurality and freedom of culture. These institutions are critical to preserving each nation's national identity and traditions. In other words, culture must be subsidized to better adapt to its plurality and freedom, as is the case with national heritages, libraries, museums and public archives – or the witnesses of our past (Havel, 1992).

As a final touch and as a historical reflection, cultural diplomacy promotes shared narratives about cultural identities. To do otherwise would not only solidify populist rhetoric and domestic prejudice against the Union, but would also make cultural totalitarianism, or worse, cultural relativism, endemic. To aspire to a 'uniform culture system' through an agreed European narrative would be to negotiate pluralism and freedom and, consequently, to contradict firstly the nature of culture and, secondly, the liberal values on which the Union was founded.

Bibliography

Banus E. (2015). Culture and Foreign Policy, 103-118.

Arndt, R. T. (2013). Culture or propaganda? Reflections on Half a Century of U.S. Cultural Diplomacy. Mexican Journal of Foreign Policy, 29-54.

Cull, N. J. (2013). Public Diplomacy: Theoretical Considerations. Mexican Journal of Foreign Policy, 55-92.

Cummings, Milton C. (2003) Cultural Diplomacy and the United States Government: A Survey, Washington, D.C. Center for Arts and Culture.

European Commission. (2016). A new strategy to put culture at the heart of EU international relations. Press re-read.

European Commission. (2016b). Towards an EU strategy for international cultural relations. Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council.

European External Action Service. (2017). Culture – Towards an EU strategy for international cultural relations. Joint Communication.

European Union. (2016). From Shared Vision to Common Action: The EU's Global Strategic Vision.

European Union. (2016b). Towards an EU Strategy for International Cultural Relations. Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council.

European Union (2017) Adminstrative Arrangements developed by the European Union National Institutes for Culture (EUNIC) in partnership with the European Commission Services and the European External Action Service, 16 May (https:// eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/2017-05-16_admin_arrangement_eunic.pdf).

Havel, Vaclav (1992) "On Politics, Morality and Civility in a Time of Transition."Summer Meditations, Knopf.

Higgot, R. (2017). Enhancing the EU's International Cultural Relations: The Prospects and Limits: Cultural Diplomacy. Institute for European Studies.

Howard, Philip K. (2011). Vaclav Havel's Critique of the West. The Atlantic.

Kim, Hwajung. (2011) Cultural Diplomacy as the Means of Soft Power in an Information Age.

La Porte and Cross. (2016). The European Union and Image Resilience during Times of Crisis: The Role of Public Diplomacy. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 1-26.

Liland, Frode (1993). Culture and Foreign Policy: An Introduction to Approaches and Theory. Institutt for Forsvarstudier, 3-30.

Melissen, J. (2005). The New Public Diplomacy: Between Theory and Practice.

Melissen, J. (2005). The New Public Diplomacy: Between Theory and Practice. In The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations (pp. 3-30). Basinggstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Michalski, Anna. (2005). The EU as a Soft Power: The Force of Persuasion. In J. Melissen, The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations (pp. 124-141). New York, N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nye, Joseph S. (2004). Soft power: The means to success in world politics. New York: Oublic Affairs.

Nye, Joseph S., (1992) Soft Power, Foreign Policy, Fall, X, pp. 150-170 1990.

Nye, Joseph. S. (2006) Think Again: Soft Power, Foreign Policy.

Richard Higgot and Virgina Proud. (2017). Populist Nationalism and Foreign Policy: Cultural Diplomacy and Resilience. Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen.

Rasmussen, S. B. (n.d.). Discourse Analysis of EU Public Diplomacy: Messages and Practices.

Triandafyllidou, Anna and Tamas Szucs. (2017). EU Cultural Diplomacy: Challenges and Opportunities. European University Institute.

Trobbiani, Riccardo. (2017). EU Cultural Diplomacy: time to define strategies, means and complementarity with Member States. Institute for European Studies.

Tuomioja, Erkki. (2009) The Role of Soft Power in EU Common Foreign Policy. International Symposium on Cultural Diplomacy. Berlin.

Walt, Stephen M. (1998) International relations: One world, many theories. Foreign Policy. Washington; Spring, pp. 29-35.

essay / Celia Olivar Gil [English version].

The global context continues to pose new challenges to European collective action at subject of development, the most important of which is migration from the Southern Mediterranean and the difficulty of articulating a well-articulated joint reaction. Aware of the urgency of status, the European Union is trying to offer a new and ambitious response in the form of the New Consensus on development (hereafter 'Consensus') which also coincides with the review of the Millennium Development Goals by the United Nations.

The Consensus is a 'framework of action' to promote the integration and coherence of cooperation to development of the European Union and its member states. This framework of action requires the adoption of those changes necessary for both EU and national legislation to comply with the diary 2030 of development Sustainable proposal by the United Nations and with the agreement of Paris on climate change.

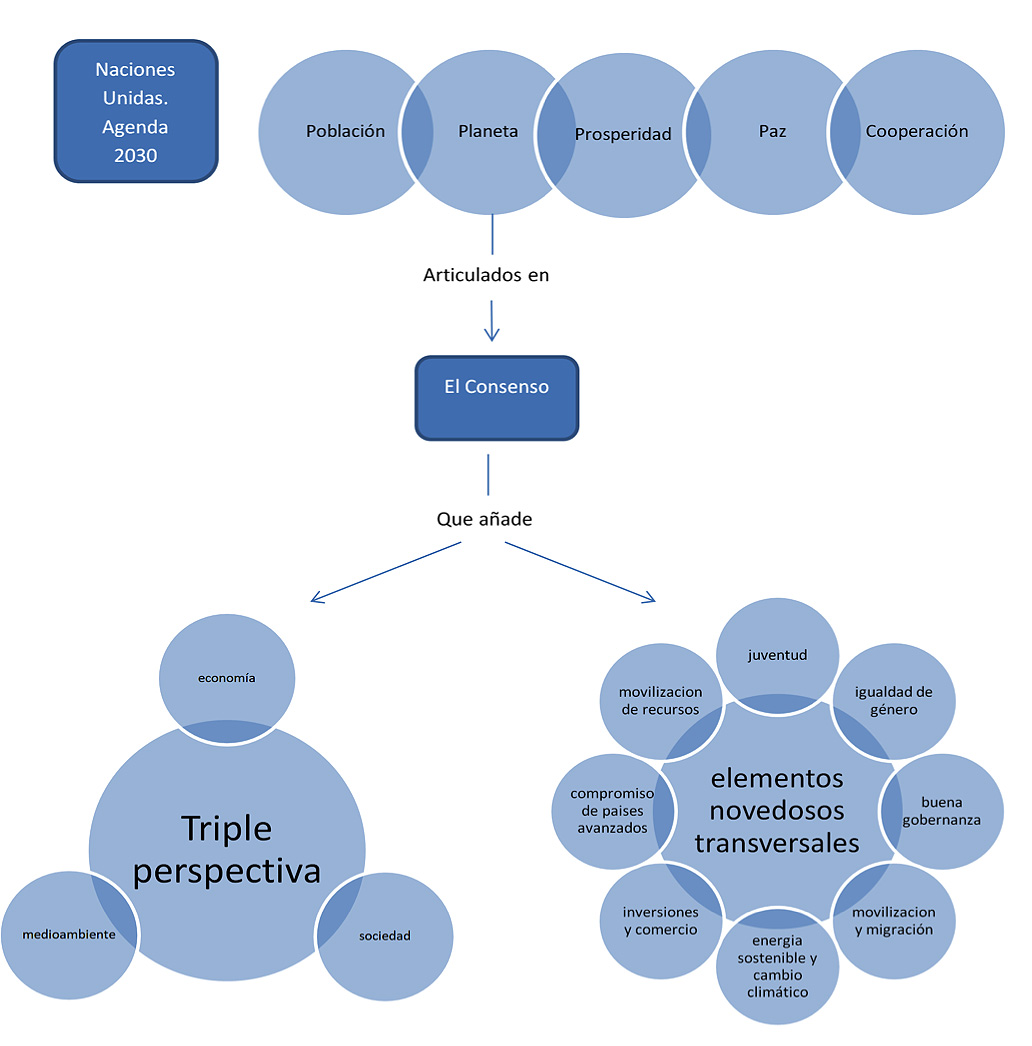

The Consensus maintains the eradication of poverty as its main goal, goal , but includes a novel vision, proposing that poverty be addressed from a triple economic, social and environmental perspective. In addition to the eradication of poverty, the Consensus aims to achieve diary 2030, and to this end articulates its five pillars: population, planet, prosperity, peace and cooperation. To this articulation, the Consensus adds some novel and cross-cutting elements, which are: emphasis on youth (meeting the basic needs of young people such as employment); gender equality; good governance (achieving a rule of law that guarantees human rights, promoting the creation of transparent institutions, participatory decision-making and independent and impartial courts); mobilization and migration; sustainable energy and climate change; Investment and trade; innovative engagement with countries at development more advanced (building new partnerships with these countries to implement diary 2030 here); domestic resource mobilization and use (effective and efficient use of resources through the "raise more, spend better" initiative).

|

|

In order to achieve all the initiatives and objectives set out above, the application of the Consensus extends to both the policies of the European Union and those of all its member states. In addition, it emphasizes that the Consensus should also be applied in new, more tailored and more multilateral partnerships involving civil society and greater participation of partner countries. The means of implementation combine traditional financial aid with more innovative forms of financing for development, such as private sector investments and mobilizing additional domestic resources for development. In terms of follow-up, the new consensus will have a regular monitoring mechanism, including accountability through the European Parliament and national parliaments and reporting obligations.

Initial assessments of the new consensus agree that it is a good synthesis of the international concerns of development. However, it raises some criticisms regarding the effective capacity to address these concerns.

First of all, as the Overseas Development Institute points out, it is not a real strategic plan, but a set of unconnected priorities. development For it to be a real strategy, the roles of the Commission and the member states would need to be determined, the thematic, sectoral and geographic priorities defined (the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) contained in the diary 2030 are treated with equal importance), and new European institutions built or existing ones (such as the International Climate Fund) used to coordinate national funds more effectively. Likewise, the Consensus should determine the form and content of cooperation with income countries average, establishing horizontal, vertical and sectoral coordination. At the same time, this coordination would require the establishment of a division of tasks within the EU to achieve a better use of resources.

Secondly, and from agreement with James Mackie (head of the department learning and quality of the European Center for the development) it is difficult to perceive to whom it is addressed and what exactly it demands. The fact that geographic and sectoral priorities remain undetermined leaves the Degree commitment of member states uncertain and if there is commitment, it will be tactical rather than explicit.

The third criticism is related to its implementation. Although the consensus is ambitious in its objectives, it lacks an adequate institutional framework and an efficient mechanism to implement its new proposals. In addition, it gives the private sector a very important role, without providing it with transparency in cases of human rights abuses or environmental damage, as Marta Latek, researcher at EPRS (European Parliamentary Research Service) explained

In terms of its objectives there are many influential actors such as CARE (the international confederation of development) who agree that it focuses too much on migration control and does not prioritize the needs of the poor. This can be seen in the fact that both in the framework cooperation with other non-EU countries, as well as the external investment plan, it prioritizes the security and commercial interests of the EU before helping the population out of poverty.

A fifth criticism makes reference letter to the political dimension. The new Consensus should integrate a holistic as well as a sustainable security concept to connect the problems of stability and democracy with those of security in EU foreign affairs. A holistic concept of development means a vision of lasting sustainability, encompassing aspects such as the condition of sustainability, social justice or democracy. (Criticism according to Henökl, Thomas and Niels Keijzer of the German Development Institute).

Finally, as far as financing is concerned, the European Parliament continues to ask member states to donate 0.7% of their annual budget for cooperation to development. Given that very few of them are able to give this 0.7%, the consensus is on the importance of private sector participation via the European External Investment Plan.

In conclusion, this document reflects the needs of the current global context but requires a series of changes in order to be fully effective and a true strategy. These changes are necessary to prevent the Consensus from remaining only theoretical.

REFERENCES

Questions and Answers: New European Consensus on development: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-17-1505_es.pdf

The new European Consensus on development: EU and Member States sign a joint strategy to eradicate poverty: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-1503_es.htm

The proposed new European Consensus on Development Has the European Commission got it right? https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/11263.pdf

New European consensus on development Will it be fit for purpose? http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2017/599434/EPRS_BRI(2017)599434_EN.pdf

Seven critical questions for review of 'European Consensus on Development ' https://www.euractiv.com/section/development-policy/opinion/sevencritical-questions-for-review-of-european-consensus-on-development/

The Future of the "European Consensus on Development" https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/average/BP_5.2016.pdf

European Union Development Policy: Collective Action in Times of Global Transformation and Domestic Crisis http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/dpr.12189/full

[Admiral James Stavridis, Sea Power. The History and Geopolitics of the World's Oceans. Penguin Press. New York City, 2017. 363 pages]

review / Iñigo Bronte Barea [English version].

In the era of globalisation and its communication society, where everything is closer and distances seem to fade away, the body of water between continents has not lost the strategic value it has always had. Historically, the seas have been both a channel for human development and instruments of geopolitical domination. It is no coincidence that the great world powers of the last 200 years have themselves been great naval powers. The dispute over maritime space is still going on today and there is nothing to suggest that the geopolitics of the seas will cease to be crucial in the future.

These principles on the importance of maritime powers have changed little since they were set out in the late 19th century by Alfred T. Mahan. Today, Sea Power. The History and Geopolitics of the World's Oceans, by Admiral James G. Stavridis, who retired in 2013 after leading the US Southern Command, the US European Command and the supreme command of NATO.

The book is the fruit of Mahan's early reading and an extensive degree program of nearly four decades on the seas and oceans with the US Navy. At the beginning of each explanation of the different sea spaces, Stavridis recounts his brief experience in that sea or ocean, then continues with the history, and the development they have had, until arriving at their current context. Finally, there is a projection of the near future of the world from the perspective of marine geopolitics.

Pacific: China's emergence

Admiral J.G. Stavridis begins his voyage in the Pacific Ocean, which he categorises as "the mother of all oceans" because of its immensity, since it alone is larger than the entire land surface of the planet combined. Another remarkable point is that in its vastness there is no considerable landmass, although there are islands all over the world subject, with very diverse cultures. This is why the sea dominates the geography of the Pacific like nowhere else on the planet.

|

The great dominator of this marine space is Australia, which is very much aware of what might happen politically in the island archipelagos in its vicinity. It was Europeans, however, who explored the Pacific well (Magellan was the first, around 1500) and tried to connect it with their world in a way that was not merely transitory and commercial, but stable and lasting.

The United States began its presence in the Pacific with the acquisition of California (1840), but it was not until the annexation of Hawaii (1898) that the huge country was definitively catapulted into the Pacific. The first time this ocean emerged as a total war zone was in 1941 when Pearl Harbour was massacred by the Japanese.

With the return of peace, the Japanese revival and the emergence of China, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong caused trans-Pacific trade to overtake the Atlantic for the first time in the 1980s, and this trend is still continuing. This is because the Pacific region contains the world's major powers on its shores.

degree program At area geopolitics a major arms race is taking place in the Pacific, with North Korea as a major focus of global tension and uncertainty.

Atlantic: from the Panama Canal to NATO

As for the Atlantic Ocean, Stavridis refers to it as the cradle of civilisation, since the Mediterranean is included among its territories, and even more so if we consider it as the nexus between the peoples of the Americas and Africa and Europe. It has two great seas of great historical importance, the Caribbean and the Mediterranean.

Undoubtedly the historical figure of this ocean is Christopher Columbus, since his arrival in America (Bahamas 1492) initiated a new historical period that ended with practically the entire American continent being colonised by the European powers in the following centuries. While Portugal and Spain concentrated on the Caribbean and South America, the British and the French concentrated on North America.

During the First World War, the Atlantic became an essential transit zone for the war development as the United States transported troops, war materials and goods to Europe during the conflict. It was here that the idea of an Atlantic community began to take shape, leading to the creation of NATO.

As for the Caribbean, the author sees it as a region that is rooted in the past. Its colonisation was characterised by the arrival of slaves to exploit the region's natural resources for purposes of economic interest to the Spanish. In turn, this process was characterised by the desire to convert the indigenous population to Christianity.

The Panama Canal is a driving force for the region's Economics , but Central America is also sailing along the coasts of the countries with the highest violence fees on the planet. Admiral Stavridis sees the Caribbean coast as a kind of Wild West, which in some places has evolved little since the days of pirates, and where drug cartels now operate with impunity.

Since the 1820s, with the Monroe Doctrine, the United States carried out a series of interventions through its navy to bolster regional stability and keep Europeans out of places such as Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Central America. In the 20th century, politics was dominated by caudillos, and soon communism and the Cold War came with them to the Caribbean, with Cuba as ground zero.

Indian Ocean and Arctic: from unknown to risky

The Indian Ocean has less history and geopolitics than the other two great oceans. Despite this, its tributary seas have gained geopolitical importance in the post-World War II era with the rise of global shipping and the export of oil from the Gulf region. The Indian Ocean today could be seen as a region for wielding smart power rather than hard power. While the slave trade and piracy have dwindled almost everywhere, they are still present in parts of the Indian Ocean. It is a region where countries around the world could work together to combat these common problems.

The history of the Indian Ocean does not inspire confidence about the potential for peaceful governance in the years to come. An important core topic to unlock the region's potential would be to resolve the existing conflicts between India and Pakistan (a conflict with the risk of nuclear weapons) and the Shia-Sunni divide in the Persian Gulf, issues that make it a very volatile region. Due to tensions in the Gulf countries, the region is today a kind of cold war between the Sunnis, led by Saudi Arabia, and the Shiites, led by Iran, and between these two sides, the United States, with its Fifth Fleet, is at the centre.

Finally, the Arctic is currently an unknown quantity. Stavridis sees it as both a promise and a danger. Over the centuries, all oceans and seas have been the site of epic battles and discoveries, but there is one exception: the Arctic Ocean.

It seems clear that this exceptionality is coming to an end. The Arctic is an emerging maritime frontier with increasing human activity, rapidly melting ice shelves and significant hydrocarbon resources coming within reach. However, there are major risks that will dangerously condition the exploitation of this region, such as weather conditions, unclear governance due to the confluence of five bordering countries (Russia, Norway, Canada, the United States and Denmark), and geopolitical competition between NATO and Russia, whose relations have deteriorated in recent years.

Showing the range 51 - 54 of 54 results.