Ruta de navegación

Blogs

US Southern Command highlights Iranian interest in consolidating Hezbollah's intelligence and funding networks in the region

-

Throughout 2019, Rosneft tightened its control over PDVSA, marketing 80% of production, but US sanctions forced it to leave the country.

-

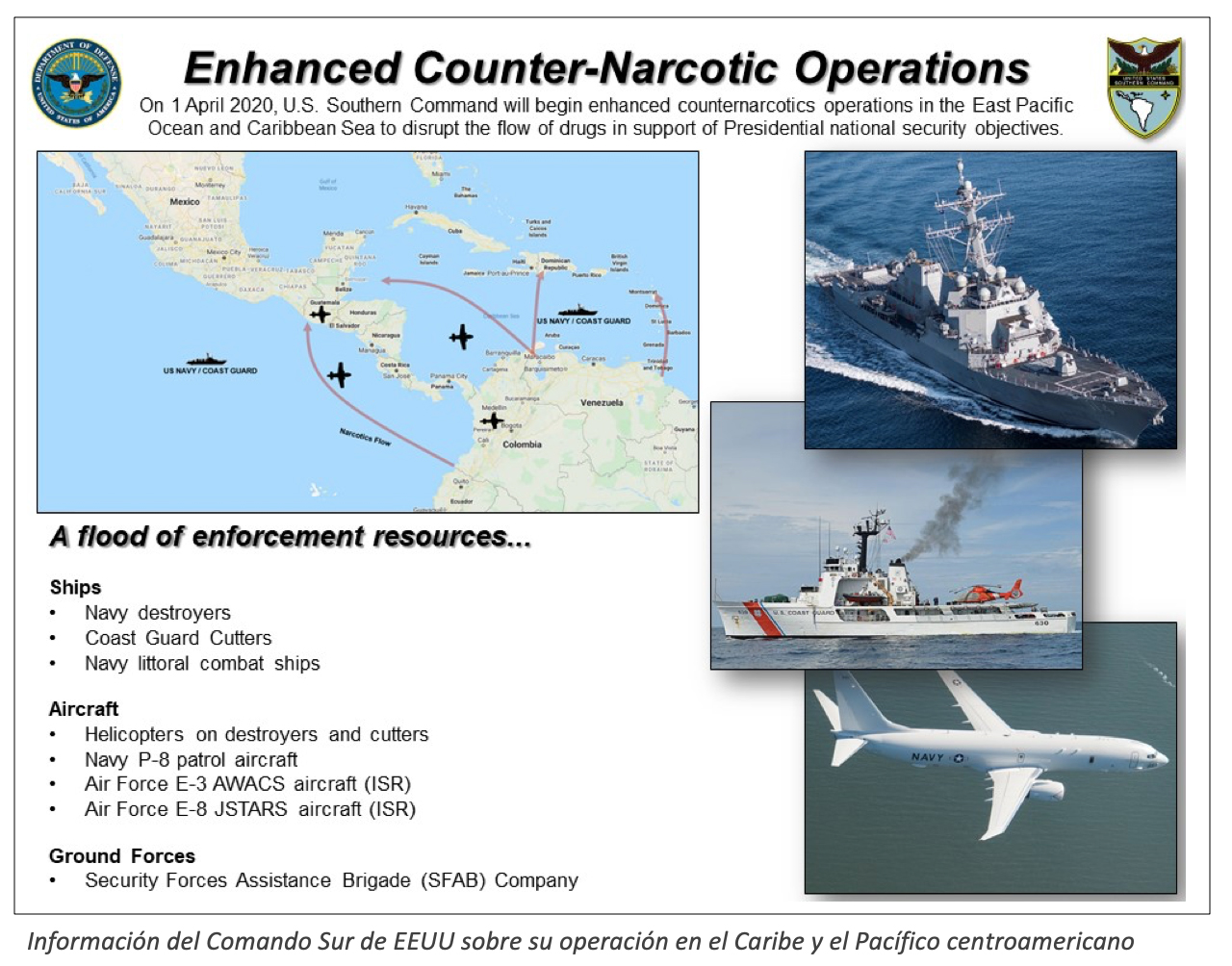

The arrival of Iranian Revolutionary Guard troops comes amid a US naval and air deployment in the Caribbean, not far from Venezuelan waters.

-

The Iranians, once again beset by Washington's sanctions, return to the country that helped them circumvent the international siege during the era of the Chávez-Ahmadinejab alliance.

![Nicolás Maduro and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at meeting in Tehran in 2015 [Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency]. Nicolás Maduro and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at meeting in Tehran in 2015 [Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency].](/documents/10174/16849987/sra-2020-venezuela-iran-blog.jpg)

▲ Nicolás Maduro and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at a meeting in Tehran in 2015 [Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency].

report SRA 2020 / Emili J. Blasco [PDF version].

financial aid In a short period of time, Venezuela has gone from depending on Chinese loans to relying on the Russian energy sector (as was particularly evident in 2019) and then to asking for the help of Iranian oil technicians (as was seen at the beginning of 2020). If the Chinese public loans were supposed to keep the country running, Rosneft's aid was only intended to save the national oil company, PDVSA, while the Iranian Revolutionary Guard's financial aid only aims to reactivate some refineries. Whoever assists Venezuela is getting smaller and smaller, and purpose is getting smaller and smaller.

In just ten years, China's big public banks granted 62.2 billion dollars in loans to the Venezuelan government. The last of the 17 loans came in 2016; since then Beijing has ignored the knocks Nicolás Maduro has made on its door. Although since 2006 Chavismo had also received credits from Moscow (some $17 billion for the purchase of arms from Russia itself), Maduro turned to pleading with Vladimir Putin when the Chinese financial aid ended. Unwilling to give any more credit, the Kremlin articulated another way of helping the regime while ensuring immediate benefits. Thus began Rosneft's direct involvement in various aspects of the Venezuelan oil business, beyond the specific exploitation of certain fields.

This mechanism was particularly relevant in 2019, when the progressive US sanctions on Venezuela's oil activity began to have a major effect. To circumvent the sanctions on PDVSA, Rosneft became a marketer of Venezuelan oil, controlling the marketing of most of the total production (between 60 and 80 per cent).

Washington's threat to punish Rosneft also led the company to shift its business to two subsidiaries, Rosneft Trading and TNK Trading International, which in turn left the business when the US pointed the finger at them. Although Rosneft generally serves the Kremlin's geopolitical interests, the fact that it is owned by BP or Qatari funds means that the company does not so easily risk its bottom line.

The departure of Rosneft, which also saw no economic sense in continuing its involvement in reactivating Venezuela's refineries, whose paralysis has plunged the country into a generalised lack of fuel supply to the population, left Maduro with few options. The Russians abandoned the Armuy refinery at the end of January 2020, and the following month Iranians were already trying to get it up and running again. Within weeks, Iran's new involvement in Venezuela became public: Tarek el Assami, the Chavista leader with the strongest connections to Hezbollah and the Shia world, was appointed oil minister in April, and in May five cargo ships brought fuel oil and presumably refining machinery from Iran to Venezuela.

The supply did not solve much (the gasoline was barely enough for a few weeks' consumption) and the Iranian technicians, at least some of them led by the Revolutionary Guard, were unlikely to be able to fix the refining problem. Meanwhile, Tehran was getting substantial shipments of gold in return for its services (nine tonnes, according to the Trump Administration). The Iranian airline Mahan, used by the Revolutionary Guards in their operations, was involved in the transports.

Thus, suffocated by the new outline sanctions imposed by Donald Trump, Iran returned to Venezuela in search of economic oxygen and also of political partnership vis-à-vis Washington, as when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad allied with Hugo Chávez to alleviate the restrictions of the first sanctions regime that the Islamic nation suffered.

US naval and air deployment

Iran's "interference" in the Western Hemisphere had already been mentioned, among the list of risks to regional security, in the appearance of the head of the US Southern Command, Admiral Craig Faller, on Capitol Hill in Washington (in January he went to the Senate and in March to the House of Representatives, with the same written speech ). Faller referred in particular to Iran's use of Hezbollah, whose presence on the continent has been aided by Chavismo for years. According to the admiral, this Hezbollah-linked activity 'allows Iran to gather intelligence and carry out contingency planning for possible retaliatory attacks against the United States and/or Western interests'.

However, the novelty of Faller's speech lay in two other issues. On the one hand, for the first time the head of the Southern Command placed China's risk ahead of Russia's, in a context of growing rivalry between Washington and Beijing, which is also manifested in the positioning of Chinese investments in strategic infrastructure works in the region.

On the other hand, he announced a forthcoming 'increased US military presence in the hemisphere', something that began to take place at the end of March 2020 when US ships and aircraft were deployed in the Caribbean and the Pacific to reinforce the fight against drug trafficking. In the context of its speech, this increased military activity in the region was understood as a necessary notice towards extra-hemispheric countries.

"Above all, what matters in this fight is persistent presence," he said, "we have to be present on the field to compete, and we have to compete to win. Specifically, he proposed more joint actions and exercises with other countries in the region and the "recurring rotation of small special operations forces teams, soldiers, sailors, pilots, Marines, Coast Guardsmen and staff National Guard to help us strengthen those partnerships".

But the arrival of US ships close to Venezuelan waters, just days after the announcement on 26 March from New York and Miami of the opening of a macro-court case for drug trafficking and other crimes against the main Chavista leaders, including Nicolás Maduro and Diosdado Cabello, gave this military deployment the connotation of a physical encirclement of the Chavista regime.

That deployment also gave some context to two other developments shortly thereafter, offering misleading readings: the failed Operation Gideon on 3 May by a group group of mercenaries who claimed they intended to infiltrate the country for Maduro (the increased transmission capabilities acquired by the US in the area, thanks to its manoeuvres, were not used in principle in this operation), and the arrival of the Iranian ships at the end of the month (the US deployment raised suspicions that Washington could intercept the ships' advance, which did not happen).

Regional security in the Americas has been the focus of concern over the past year in Venezuela. We also review Russia and Spain's arms sales to the region, Latin America's presence in peacekeeping missions, drugs in Peru and Bolivia, and homicides in Mexico and Brazil.

![Igor Sechin, director Rosneft executive, and Nicolás Maduro, in August 2019 [Miraflores Palace]. Igor Sechin, director Rosneft executive, and Nicolás Maduro, in August 2019 [Miraflores Palace].](/documents/10174/16849987/sra-2020-resumen-ejecutivo-blog.jpg)

▲ Igor Sechin, director Rosneft executive, and Nicolás Maduro, in August 2019 [Miraflores Palace].

report SRA 2020 / summary executive[PDF version].

Throughout 2019, Latin America had several hotspots of tension - violent street protests against economic measures in Quito, Santiago de Chile and Bogotá, and against political decisions in La Paz and Santa Cruz, for example - but as these conflicts subsided (in some cases, only temporarily), the constant problem of Venezuela as the epicentre of insecurity in the region re-emerged.

With Central American migration to the United States reduced to a minimum by the Trump administration's restrictive measures, it has been Venezuelan migrants who have continued to fill the roadsides of South America, moving from one country to another, and now number more than five million refugees. The difficulties that this population increase entails for the host countries led several of them to increase their pressure on the government of Nicolás Maduro, approving in the OAS the activation of the Inter-American Reciprocal Treaty of attendance (TIAR). But that did not push Maduro out of power, nor did the assumption in January 2019 by Juan Guaidó of the position as president-in-charge of Venezuela (recognised by more than fifty countries), the failed coup a few months later or the alleged invasion of Operation Gideon in May 2020.

While Maduro may appear stabilised, the geopolitical backdrop has been shifting. The year 2019 saw Rosneft gain a foothold in Venezuela as an arm of the Kremlin, once China had stepped back as a credit provider. The risk of not recovering everything it had borrowed meant that Russia acted through Rosneft, benefiting from trading up to 80 per cent of the country's oil. However, US sanctions finally forced the departure of the Russian energy company, so that in early 2020 Maduro had no other major extra-hemispheric partner to turn to than Iran. The Islamic republic, itself subject to a second sanctions regime, thus returned to the close relationship it had maintained with Venezuela in the first period of international punishment, cultivated by the Chávez-Ahmadinejad tandem.

This Iranian presence is closely watched by the United States (coinciding with a deployment of the Southern Command in the Caribbean), which is always alert to any boost that Hezbollah - an Iranian proxy - might receive in the region. In fact, 2019 marked an important leap in the disposition of Latin American countries against this organisation, with several of them classifying it as a terrorist organisation for the first time. Argentina, Paraguay, Colombia and Honduras approved such a declaration, following the 25th anniversary in July of the AMIA bombing attributed to Hezbollah. Brazil and Guatemala pledged to do so shortly. Several of these countries have drawn up lists of terrorist organisations, which allows them to pool their strategies.

The destabilisation of the region by status in Venezuela has a clear manifestation in the reception and promotion of Colombian guerrillas in that country. issue In August, former FARC leader Iván Márquez and some other former leaders announced, presumably from Venezuelan territory, their return to arms. Both this dissident core of the FARC and the ELN had begun to consolidate at the end of the year as Colombian-Venezuelan groups, with operations not only in the Venezuelan border area, but also in the interior of the country. Both groups together have some 1,700 troops in Venezuela, of which almost 600 are Venezuelan recruits, thus constituting another shock force at Maduro's service.

Russia's exit from Venezuela comes at a time when Moscow is apparently less active in Latin America. This is certainly the case in the field of arms sales. Russia, which had become a major exporter of military equipment to the region, has seen its sales decline in recent years. While during the golden decade of the commodity boom several countries spent part of their significant revenues on arms purchases (which also coincided with the spread of the Bolivarian tide, better linked to Moscow), the collapse in commodity prices and some governmental changes have meant that in the 2015-2019 period Latin America is the destination of only 0.8 per cent of Russia's total arms exports. The United States has regained its position as the largest seller to the rest of the continent.

Spain occupies a prominent position in the arms market, as the seventh largest exporter in the world. However, it lags behind in the preferences of Latin American countries, to which it sells less defence materiel than it would be entitled to in terms of the overall volume of trade it maintains with them. Nevertheless, the level of sales increased in 2019, after a year of particularly low figures. In the last five years, Spain has sold 3.6% of its global arms exports to Latin America; in that period, its main customers were Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, Peru and Colombia.

Better military equipment might suggest greater participation in UN peacekeeping missions, perhaps as a way of keeping an army active in a context of a lack of regional deployments. However, of the total of 82,480 troops in the fourteen UN peacekeeping missions at the beginning of 2020, 2,473 came from Latin American countries, which represents only 3 per cent of the total contingent. Moreover, almost half of staff was contributed by one country, Uruguay (45.5% of regional troops). Another small country, El Salvador (12%), is the next most committed to missions, while large countries are under-represented, notably Mexico.

In terms of public safety, 2019 brought the good news of a reduction in homicides in Brazil, which fell by 19.2% compared to the previous year, in contrast to what happened in Mexico, where they rose by 2.5%. If in his first year as president, Jair Bolsonaro scored an important achievement, thanks to the management of the super security minister Sérgio Moro (a success tarnished by the increase in accidental deaths in police operations), in his first year Andrés Manuel López Obrador failed to fulfil one of his main electoral promises and was unable to break the upward trend in homicides that has invariably occurred annually throughout the terms of office of his two predecessors.

In terms of the fight against drug trafficking, 2019 saw two particularly positive developments. On the one hand, coca crops were eradicated for the first time in the VRAEM, Peru's largest production area. Given its difficult accessibility and the presence of Shining Path strongholds, the area had previously been excluded from the operations of subject. On the other hand, the change of presidency in Bolivia meant, according to the US, a greater commitment by the new authorities to combat illicit coca cultivation and interdict drug shipments coming from Peru. In recent years Bolivia has become the major cocaine distributor in the southern half of South America, connecting Peruvian and Bolivian production with the markets of Argentina and especially Brazil, and with its export ports to Europe.

![Venezuelans leaving the country to seek a livelihood in a host country [UNHCR UNHCR]. Venezuelans leaving the country to seek a livelihood in a host country [UNHCR UNHCR].](/documents/10174/16849987/informe-precovid-blog.jpg)

Venezuelans leaving the country to look for a livelihood in a place of refuge [UNHCR UNHCR].

report SRA 2020 / presentation

The Covid-19 pandemic has radically altered security assumptions around the world. The emergence of the coronavirus moved from China to Europe, then to the United States and then to the rest of the Western Hemisphere. Already economically handicapped by its dependence on commodity exports since the beginning of the Chinese slowdown, Latin America suffered from the successive restrictions in the different geographical areas, and finally also entered a crisis of production and consumption and a health and labour catastrophe. The region is expected to be one of the hardest hit, with effects also in the field of security.

This annual report , however, focuses on American regional security in 2019. Although in some respects it includes events from the beginning of 2020, and therefore some early effects of the pandemic, the impact of the pandemic on issues such as regional geopolitics, state budgetary difficulties, organised crime and citizen security can be found at report next year.

To the extent that other security developments in 2019 have been somewhat transitory in recent months, Venezuela has remained the main focus of regional insecurity over the past year. At report we analyse Iran's return to the Caribbean country, after first China and then Russia preferred not to see their own economic interests harmed; we also note the consolidation of the ELN and part of the ex-FARC as binational Colombian-Venezuelan groups.

In addition, we highlight the progress made in the first time that Hezbollah has been designated by several countries as a terrorist organisation, group , and we provide figures on the drop in Russian arms sales to Latin America and the relative lack of marketing in the region of the defence material produced by Spain. We also quantify the contribution of Latin American troops to UN peacekeeping missions, as well as Bolsonaro's success and AMLO's failure in the evolution of homicides in Brazil and Mexico. In terms of drug trafficking, 2019 saw the first coca crop eradication operation in the VRAEM, the most complicated area of Peru in the fight against drugs.

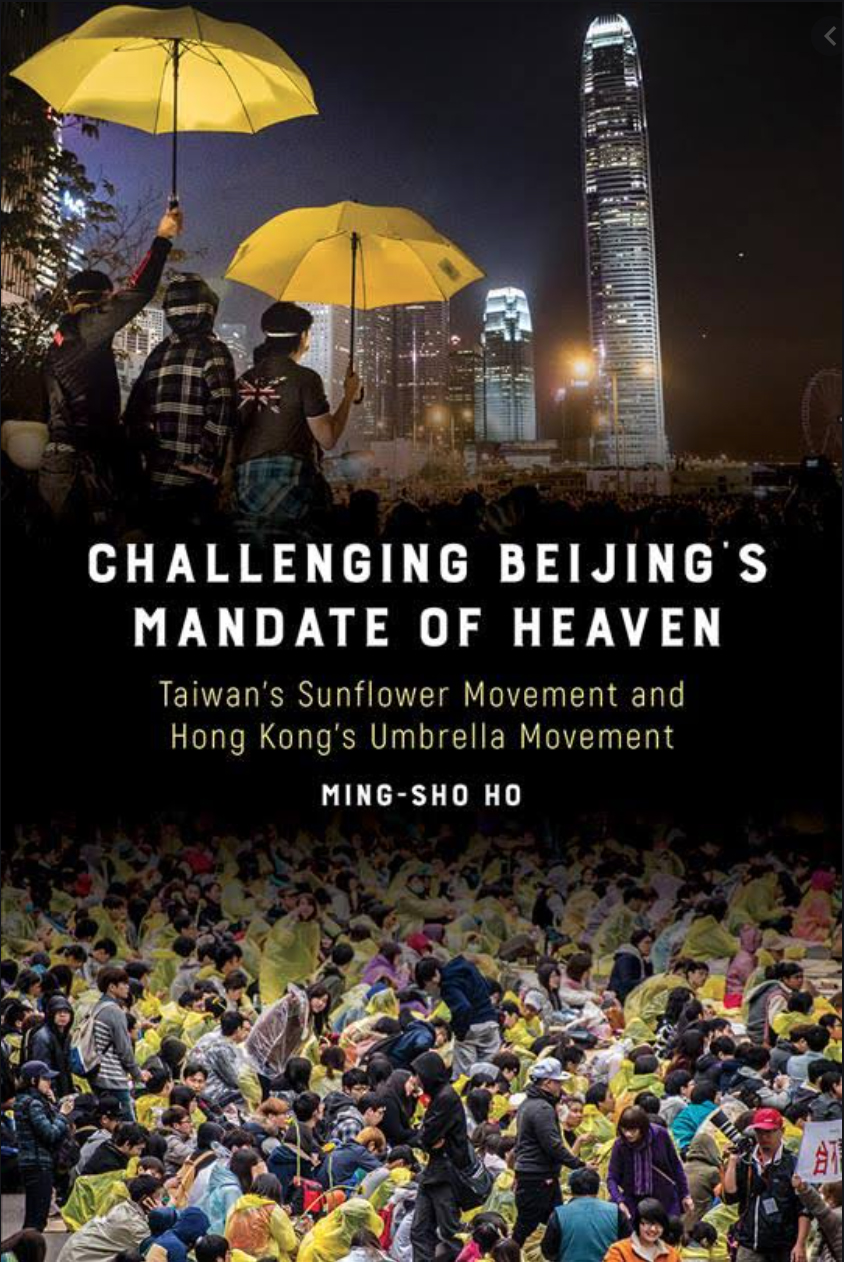

[Ming-Sho Ho, Challenging Beijing's Mandate of Heaven. Taiwan's Sunflower and Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement. Temple University Press. Philadelphia, 2019. 230 p.]

review / Claudia López

Taiwan's Sunflower Movement and Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement achieved international notoriety during 2014, when they challenged the Chinese regime's 'Mandate of Heaven', to use the image that gives degree scroll to the book. The book analyses the origins, processes and also the outcomes of both protests, at a time of consolidation of the rise of the People's Republic of China. Challenging Beijing's Mandate of Heaven provides a detailed overview of where, why and how these movements came into being and achieved relevance.

Taiwan's Sunflower Movement and Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement achieved international notoriety during 2014, when they challenged the Chinese regime's 'Mandate of Heaven', to use the image that gives degree scroll to the book. The book analyses the origins, processes and also the outcomes of both protests, at a time of consolidation of the rise of the People's Republic of China. Challenging Beijing's Mandate of Heaven provides a detailed overview of where, why and how these movements came into being and achieved relevance.

Taiwan's Sunflower Movement developed in March and April 2014, when citizen demonstrations protested against the approval of a free trade agreement with China. Between September and December of the same year, the Umbrella Movement staged 79 days of protests in Hong Kong demanding universal suffrage to elect the highest authority in this enclave of special status within China. These protests attracted international attention for their peaceful and civilised organisation.

Ming-Sho Ho begins by describing the historical background of Taiwan and Hong Kong from their Chinese origins. He then analyses the status of the two territories so far this century, when Taiwan and Hong Kong have begun to face increased pressure from China. It also reviews the similar economic circumstances that produced the two waves of youth revolts. The second part of the book analyses the two movements: the voluntary contributions, the decision-making process and its improvisation, the internal power shift, the political influences and the challenges of the initiative. The book includes appendices with the list of Taiwanese and Hong Kong people interviewed and the methodology used for the analysis of the protests.

Ming-Sho Ho was born in 1973 in Taiwan and has been a close observer of the island's social movements; during his time as a student of doctorate in Hong Kong he also closely followed the political discussion in the former British colony. He is currently researching initiatives for promote renewable energy in East Asian nations.

Being from Taiwan gave him access to the Sunflower Movement and allowed him to build close relationships with several of its key activists. He was able to witness some of the students' internal meetings and conduct in-depth interviews with students, leaders, politicians, NGO activists, journalists and university professors. This provided him with a variety of sources for his research.

Although they are two territories with different characteristics - Hong Kong is under the sovereignty of the People's Republic of China, but enjoys autonomy management assistant; Taiwan remains independent, but its statehood is challenged - both represent a strategic challenge for Beijing in its consolidation as a superpower.

The author's sympathy for these two movements is obvious throughout the book, as is his admiration for the risk taken by these student groups, especially in Hong Kong, where many of them were convicted of 'public nuisance' and 'disturbing the peace' and, in many cases, sentenced to more than a year in prison.

The two movements had a similar beginning and a similar development beginning, but each ended in a very different way. In Taiwan, thanks to the initiative, the free trade agreement with China failed and was withdrawn, and the protesters were able to call hold a farewell rally to celebrate this victory. In Hong Kong, police repression succeeded in stifling the protest and a final massive raid brought a disappointing end for the protesters. However, it is possible that without the experience of those mobilisations, the new student reaction that throughout 2019 and early 2020 in Hong Kong has put the highest Chinese authorities on the ropes would not have been possible.

ESSAY / Emilija Žebrauskaitė

Introduction

While the Western Westphalian State - and, consequently, the Western legal system - became the default in most parts of the world, Africa with its traditional ethics and customs has a lot to offer. Although the positive legalism is still embraced, there is a tendency of looking at the indigenous traditions for the inspiration of the system that would be a better fit in an African setting. Ubuntu ethics has a lot to offer and can be considered a basis for all traditional institutions in Africa. A great example of Ubuntu in action is the African Traditional Justice System which embraces the Ubuntu values as its basis. This article will provide a conceptualization of Ubuntu philosophy and will analyse its applications in the real-world scenarios through the case of Gacaca trials in Rwanda.

Firstly, this essay will define Ubuntu: its main tenants, how Ubuntu compares with other philosophical and ethical traditions, and the main criticism of Ubuntu ethics. Secondly, the application of Ubuntu ethics through African Indigenous Justice Systems will be covered, naming the features of Ubuntu that can be seen in the application of justice in the African setting, discussing the peace vs. justice discussion and why one value is emphasized more than another in AIJS, and how the traditional justice in Africa differs from the Western one.

Lastly, through the case study of Gacaca trials in post-genocide Rwanda, this essay seeks to demonstrate that the application of the traditional justice in the post-genocide society did what the Western legalistic system failed to do - it provided a more efficient way to distribute justice and made the healing of the wounds inflicted by the genocide easier by allowing the community to actively participate in the judicial decision-making process.

It is the opinion of this article that while the African Traditional Justice System has it's share of problems when applied in modern-day Africa, as the continent is embedded into the reality of the Westphalian state, each state being a part of the global international order, the Western model of justice is eroding the autonomy of the community which is a cornerstone of African society. However, the values of Ubuntu ethics persist, providing a strong basis for traditional African institutions.

Conceptualization of Ubuntu

The word Ubuntu derives from the Bantu language group spoken widely across sub-Saharan Africa. It can be defined as "A quality that includes the essential human virtues; compassion and humanity" (Lexico, n.d.) and, according to Mugumbate and Nyanguru, is a homogenizing concept, a "backbone of African spirituality" in African ontology (2013). "Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu" - a Zulu phrase meaning "a person is a person through other persons" is one of the widely spread interpretations of Ubuntu.

In comparison with non-African philosophical thoughts, there can be found similarities between Ubuntu and the traditional Chinese as well as Western ethics, but when it comes to the modern Western way of thought, the contrast is striking. According to Lutz (2009), Confucian ethics, just like Ubuntu ethics, view the institution of family as a central building block of society. An Aristotelian tradition which prevailed in the Western world until Enlightenment had some characteristics similar to Ubuntu as well, namely the idea of Aristotle that human being is a social being and can only reach his true potential through the community (Aristotle, 350 B.C.E.). However, Thomas Hobbes had an opposite idea of human nature, claiming that the natural condition of man is solidarity (Hobbes, 1651). The values that still prevail in Ubuntu ethics, therefore, are rarely seen in modern liberal thought that prevails in the Western World and in the international order in general. According to Lutz (2009) "Reconciling self-realization and communalism is important because it solves the problem of moral motivation" which Western modern ethics have a hard time to answer. It can be argued, therefore, that Ubuntu has a lot to offer to the global ethical thought, especially in the world in which the Western ideas of individualism prevail and the values of community and collectivism are often forgotten.

Criticisms

However, while Ubuntu carries values that can contribute to global ethics, as a philosophical current it is heavily criticised. According to Metz (2011), there are three main reasons why Ubuntu receives criticism: firstly, it is considered vague as a philosophical thought and does not have a solid framework; secondly, it is feared that due to its collectivist orientation there is a danger of sacrificing individual freedoms for the sake of society; and lastly, it is thought that Ubuntu philosophy is applicable and useful only in traditional, but not modern society.

When it comes to the reproach about the vagueness of Ubuntu as a philosophical thought, Thaddeus Metz examines six theoretical interpretations of the concept of Ubuntu:

U1: An action is right just insofar as it respects a person's dignity; an act is wrong to the extent that it degrades humanity.

U2: An action is right just insofar as it promotes the well-being of others; an act is wrong to the extent that it fails to enhance the welfare of one's fellows.

U3: An action is right just insofar as it promotes the well-being of others without violating their rights; an act is wrong to the extent that it either violates rights or fails to enhance the welfare of one's fellows without violating rights.

U4: An action is right just insofar as it positively relates to others and thereby realises oneself; an act is wrong to the extent that it does not perfect one's valuable nature as a social being.

U5: An action is right just insofar as it is in solidarity with groups whose survival is threatened; an act is wrong to the extent that it fails to support a vulnerable community.

U6: An action is right just insofar as it produces harmony and reduces discord; an act is wrong to the extent that it fails to develop community (Metz, 2007).

While arguing that the concept U4 is the most accepted in literature, Matz himself argues in favour of the concept U6 as the basis of the ethics is rooted not in the subject, but in the object (Metz, 2007).

The fear that Ubuntu tenants make people submissive to authority and collective goals, giving them a very strong identity that might result in violence against other groups originates, according to Lutz (2009), from a faulty understanding of Ubuntu. Even though the tribalism is pretty common in the African setting, it does not derive from the tenants of Ubuntu, but a corrupted idea of this ethical philosophy. Further criticism on the idea that collectivism might interfere with individual rights or liberties can also be denied quoting Lutz, who said that "Ethical theories that tell us we must choose between egoism and altruism, between self-love and love of others, between prudence and morality, or one's good and the common good are individualistic ethical theories" and therefore have nothing in common with ideas of Ubuntu, which, unlike the individualistic theories, reconciles the common and staff good and goals.

The third objection, namely the question of whether Ubuntu ethics remain useful in the modern society which functions according to the Westphalian State model is challenged by Metz (2011). While it is true that Ubuntu developed in a traditional setting in which the value of human beings was based on the amount of communal life a human has lived (explaining the respect for the elders and the ancestors in African setting), a variant concept of dignity that in no way can be applied in a modern setting, there are still valuable ethical norms that can be thought by Ubuntu. Metz (2011) provides a concept of human dignity based on Ubuntu ideas, which, as he argues, can contribute to ethics in the modern African setting: "individuals have dignity insofar as they have communal nature, that is, the inherent capacity to exhibit identity and solidarity with others".

The Ubuntu ethics in African Indigenous Justice System

The institutionalisation and centralisation of power in the hands of the Westphalian State takes away the power from the communities which are central to the lifestyle in Africa. However, the communal values have arguably persisted and continue to directly oppose the centralisation. While the Westphalian State model seems to be functioning in the West, there are many good reasons to believe that Africa must look for inspiration in local traditions and customs (Malisa & Nhengeze, 2018). Taking into consideration the Ubuntu values, it is not difficult to understand why institutionalisation has generally not been very successful in African setting (Mugumbate & Nyanguru, 2013), as a place where the community is morally obliged to take care of its members, there is little space for alienated institutions.

Generally, two justice systems are operating alongside each other in many African societies: the state-administered justice system and the African Indigenous Justice System (AIJS). According to Elechi, Morris & Schauer, the litigants can choose between the state tribunal and AIJS, and can apply to be judged by the state if they do not agree with the sentence of the AIJS (Elechi, Morris, & Schauer, 2010). However, Ubuntu values emphasise the concept of reconciliation: "African political philosophy responds easily and organically to the demands for the reconciliation as a means of restoring the equilibrium of the flow of life when its disturbed" (Nabudere, 2005). As the national court interventions often disharmonize the community by applying the "winner takes it all" approach, and are sometimes considered to be corrupt, there is a strong tendency for the communities to insist on bringing the offender to the AIJS tribunal (Elechi, Morris, & Schauer, 2010).

African Indigenous Justice System is a great example of Ubuntu values in action. The system operates on the cultural norm that important decision should be reached by consensus of the whole group as opposed to the majority opinion. AIJS is characterised by features such as the focus on the effects the offence had on victims and the community, the involvement of the litigants in the active definition of harms and the resolution of the trial, the localisation and decentralisation of authority, the importance of the restoration of harm, the property or relationship, the understanding that the offender might be a victim of the socioeconomic conditions; with the main objective of the justice system being the restoration of relationships, healing, and reconciliation in the community (Elechi, Morris, & Schauer, 2010). Underlying this system is the concept of Ubuntu, which "leads to a way of dealing with the social problems which are very different from the Western legalistic, rule-based system which had become the global default" (Baggini, 2018).

One of the reasons why AIJS can be considered exemplary is its ability to avoid the alienation of the Western courts in which the victim, the offender, and everybody else seem to be represented, but neither victim nor offender can directly participate in the decision making. The system which emphasises reconciliation and in which the community is in charge of the process is arguably much more effective in the African setting, where communities are generally familiar and close-knit. As the offender is still considered a part of the community and is still expected to contribute to its surroundings in the future, the participation in the trial and the decision making is important to the reconciliation: "unlike adjudicated justice, negotiated justice is not a winner take it all justice. Resolution can be reached where the offender, the community, and the victim are each partially wrong" (Elechi, Morris, & Schauer, 2010). As there is very little hope for an offender to be reintegrated into a close community without forgiving and forgiveness from both parties, this type of approach is pivotal.

Another interesting feature of AIJS is the assumption that the offender is not inherently bad in himself, but is primarily a marginalised victim, who does not have the same opportunities as other members of the community to participate in the economic, political, and social aspects of the group, and who can be made right if both the offender and the community make effort (Elechi, Morris, & Schauer, 2010). This concept differs from the Western Hobbesian idea of human beings being inherently corrupt and is much closer to traditional Western Aristotelian ethics. What makes the African concept different, however, is the focus which is not on the virtue of the person himself, but rather on the relationship the offender has with his family and community which, although violated by the offence, can and should be rebuilt by amendments (Elechi, Morris, & Schauer, 2010).

The Gacaca Trials

The Gacaca trials are the state-administered structure which uses communities (around a thousand of them) as a basis for judicial forums (Meyerstein, 2007). They were introduced by the Rwandan government as an alternative to national justice after the Rwandan genocide.

During the colonial times, Rwanda was indirectly ruled by the colonisers through local authorities, namely the Tutsi minority (Uvin, 1999). The Hutu majority were considered second class citizens and by the time of independence were holding deep grievances. The Rwandan Revolution of 1959-1961 overthrew the monarchy and the ruling Tutsi elite. After the independence from the colonial regime, Rwanda was ruled by the Party of Hutu Emancipation Movement, which was supported by the international community on the grounds of the idea that the government is legitimate as it represents the majority of the population - the Hutu (ibid.) During the period of transition, ethnic violence against Tutsi, forcing many of them to leave the country, happened (Rettig, 2008). In 1990 the Rwandan Patriotic Army composed mostly by the Tutsi exiles invaded Rwanda from neighbouring Uganda (ibid.) The incumbent government harnessed the already pre-existing ethnic to unite the Hutu population to fight against the Tutsi rebels. The strategy included finding a scapegoat in an internal Tutsi population that continued to live in Rwanda (Uvin, 1999). The genocide which soon followed took lives of 500,000 to 800,000 people between April and July of the year 1994 when the total population at the time is estimated to have been around 8 million (Drumbl, 2020). More than 100,000 people were accused and waited in detention for trials, creating a great burden on a Rwandan county (Schabas, 2005).

According to Meyerstein (2007), the Gacaca trials were a response to the failure of the Western-styled nation court to process all the suspects of the genocide. Gacaca trials were based on indigenous local justice, with Ubuntu ethics being an underlying element of the system. The trials were traditionally informal, organic, and patriarchal, but the Rwandan government modernised the indigenous justice system by establishing an organisational structure, and, among other things, making the participation of women a requirement (Drumbl, 2020).

The application of Gacaca trails to do justice after the genocide was not always well received by the international community. The trials received criticism for not complying with the international standards for the distribution of justice. For example, Amnesty International invoked Article 14 of the ICCPR and stated that Gacaca trials violated the right of the accused to be presumed innocent and to the free trial (Meyerstein, 2007). There are, undoubtedly, many problems that can be assigned to the system of Gacaca when it comes to the strict norms of the international norms.

The judges are drawn from the community and arguably lack the official legal training, the punitive model of the trials that arguably have served for many as an opportunity for staff revenge, and the aforementioned lack of legal protection for the accused are a few of many problems faced by the Gacaca trials (Rettig, 2008). Furthermore, the Gacaca trials excluded the war criminals from the prosecution - there were many cases of the killings of Hutu civilians by Tutsis that formed the part of the Rwandan Patriotic Front army (Corey & Joireman, 2004). This was seen by many as a politicised application of justice, in which, by creating two separate categories of criminals - the crimes of war by the Tutsis that were not the subject of Gacaca and the crimes of the genocide by the Hutus that were dealt with by the trials - the impunity and high moral ground was granted for the Tutsi (ibid). This attitude might bring results that are contrary to the initial goal of the community-based justice - not the reconciliation of the people, but the further division of the society along the ethnic lines.

However, while the criticism of the Gacaca trials is completely valid, it is also important to understand, that given the limited amount of resources and time, the goal of bringing justice to the victims of the genocide is an incredibly complex mission. In the context of the deeply wounded, post-genocidal society in which the social capital was almost non-existent, the ultimate goal, while having justice as a high priority, was first of all based on Ubuntu ethics and focused more on peace, retribution, and social healing. The utopian perfectness expected by the international community was nearly impossible, and the Gacaca trials met the goal of finding the best possible solutions in the limits of available resources. Furthermore, the criticism of international community often seemed to stem not so much from the preoccupation for the Rwandan citizens, as from the fact that a different approach to justice threatens the homogenising concept of human rights "which lashes out to squash cultural difference and legal pluralism by criticising the Gacaca for failures to approximate canonised doctrine" (Meyerstein, 2007).

While it is true that even Rwandan citizens often saw Gacaca as problematic, whether the problems perceived by them were similar to those criticised by the international community is dubious. For example, Rwanda's Supreme Court's response to the international criticism was the provision of approach to human rights which, while not denying their objectivity, also advocates for the definition that better suits the local culture and unique circumstances of post-genocide Rwanda (Supreme Court of Rwanda, 2003). After all, the interventions from the part of the Western world on behalf of the universal values have arguably created more violence historically than the defended values should ever allow. The acceptance that Gacaca trials, while imperfect, contributed positively to the post-genocide Rwandan society has the grave implications that human rights are ultimately a product of negotiation between global and local actors" (Meyerstein, 2007) which the West has always refused to accept. However, it is the opinion of this article that exactly the opposite attitude, namely that of better intercultural understanding and the search for the solutions that are not utopian but fit in the margins of the possibilities of a specific society, are the key to both the efficiency and the fairness of a justice system.

Conclusion

The primary end of the African Indigenous Justice System is to empower the community and to foster reconciliation through a consensus that is made by the offenders, the victims, and the community alike. It encourages to view victims as people who have valuable relationships: they are someone's daughters, sons, fathers - they are important members of society. Ubuntu is the underlying basis of the Indigenous Justice System and African ethnicity in general. While the AIJS seems to be functioning alongside the state's courts, in the end, the centralization and alienation from the community are undermining these traditional values that flourish in the African setting. The Western legalistic system helps little when it comes to the main goal of justice in Africa - the reconciliation of the community, and more often than not only succeeds in creating further discord. While the criticism of Gacaca trials was undoubtedly valid, it often stemmed from the utopian idealism that did not take the actual situation of a post-genocide Rwanda into consideration or the Western universalism, which was threatened by the introduction of a justice system that in many ways differs from the positivist standard. It is the opinion of this article, therefore, that more autonomy should be granted to the communities that are the basic building blocks of most of the African societies, with the traditional values of Ubuntu being the basis of the African social institutions.

REFERENCES

Lexico. (n.d.). Lexicon. Retrieved from https://www.lexico.com/definition/ubuntu

Mugumbate, J., & Nyanguru, A. (2013). Exploring African Philosophy: The Value of Ubuntu in Social Work. African Journal of Social Work, 82-100.

Metz, T. (2011). Ubuntu as a moral theory and human rights in South Africa. African Human Rights Law Journal, 532-559.

Metz, T. (2007). Towards an African Moral Theory. The Journal of Political Philosophy.

Lutz, D. W. (2009). African Ubuntu Philosophy and Global Management. Journal of Business Ethics, 313-328.

Hobbes, T. (1651). Leviathan.

Aristotle. (350 B.C.E.). Politics.

Malisa, M., & Nhengeze, P. (2018). Pan-Africanism: A Quest for Liberation and the Pursuit of a United Africa. Genealogy.

Elechi, O., Morris, S., & Schauer, E. (2010). Restoring Justice (Ubuntu): An African Perspective. International Criminal Justice Review.

Baggini, J. (2018). How the World Thinks: A Global History of Philosophy. London: Granta Books.

Meyerstein, A. (2007). Between Law and Culture: Rwanda's Gacaca and Postolocial Legality. Law & Social Inquiry.

Corey, A., & Joireman, S. (2004). African Affairs. Retributive Justice: the Gacaca Courts in Rwanda.

Nabudere, D. W. (2005). Ubuntu Philosophy. Memory and Reconciliation. Texas Scholar Works, University of Texas Library.

Rettig, M. (2008). Gacaca: Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation in Postconflict Rwanda? African Studies Review.

Supreme Court of Rwanda. (2003). Developments on the subject of the report and different correspondences of Amnesty International. Départements des Jurisdictions Gacaca.

Drumbl, M. A. (2020). Post-Genocide Justice in Rwanda. Journal of International Peacekeeping.

Uvin, P. (1999). Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence. Comparative Politics, 253-271.

Schabas, W. A. (2005). Genocide Trials and Gacaca Courts. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 879-895.

![Artistic image of a Pakistani Rupee [Pixabay]. Artistic image of a Pakistani Rupee [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-country-risk-report-blog.jpg)

▲ Artistic image of a Pakistani Rupee [Pixabay].

COUNTRY RISK REPORT / M. J. Moya, I. Maspons, A. V. Acosta

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The government of Prime Minister (PM), Imran Khan, was slowly moving towards economic, social, and political improvements, but all these efforts might be hampered by the recent outbreak of the COVID-19 virus since the government must temporarily shift its focus and resources to keeping its population safe. Additionally, high logistical, legal, and security challenges still generate an uncompetitive operating environment and thus, an unattractive market for foreign investment in Pakistan.

Firstly, in relation to the country's economic outlook, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was expected to gradually recover around 5% in the upcoming years. However, according to latest estimates, this growth will suffer a negative impact and fall to around 2%, straining the country's most recent recorded improvements. On the other hand, in the medium to long-term, Pakistan will benefit from the success of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is a strategic economic project aiming to improve infrastructure capacity in the country. Pakistan is also facing an energy crisis along with a growing demand from a booming population that hinder a proper economic progress.

Secondly, Pakistan's political future will be shaped by Khan's ability to transform his short-term policies into long-term strategies. However, in order to achieve this, the government must tackle the root causes of political instability in Pakistan, such as long-lasting corruption, the constant military influence in decision-making processes, the historical discussion among secularism and Islamism, and the new challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, PM Khan's progressive reforms could represent the beginning towards a "Naya Pakistan" ("New Pakistan").

Thirdly, Pakistan's social stability is contextualized within a high risk of terrorist attacks due to its internal security gaps. The ethnic dilemma among the provinces along with the government's violent oppression of insurgencies will continue to impede development and social cohesion within the country. This will further aggravate in light of a current shortage of resources and the impacts of climate change.

In addition, in terms of Pakistan's security outlook, the country is expected to tackle terrorist financing and money laundering networks in order to avoid being blacklisted by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Nonetheless, due to a porous border with Afghanistan, Pakistan faces drug trafficking challenges that further destabilize national security. Finally, the turbulent Indo-Pakistani relation is the most significant conflict for the South Asian country. The disputed region of Jammu and Kashmir, a possible nuclear confrontation, and the increase of nationalist movements along the Punjab region, hamper regional and international peace.

![Revolutionary Guard Commando Naval Exercises in the Strait of Hormuz in 2015 [Wikipedia]. Revolutionary Guard Commando Naval Exercises in the Strait of Hormuz in 2015 [Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/iran-nueva-guerra-fria-blog.jpg)

▲ Revolutionary Guard Commando Naval Exercises in the Strait of Hormuz in 2015 [Wikipedia].

essay / Ana Salas Cuevas

The Islamic Republic of Iran, also known as Persia, is a country of great geopolitical importance. It is a regional power not only because of its strategic location, but also because of its vast hydrocarbon resources, which make Iran the fourth largest country in terms of proven oil reserves and the first in terms of gas reserves[1].

We are talking about one of the most important countries in the world for three main reasons. The first, mentioned above, is its immense oil and gas reserves. entrance Secondly, because Iran controls the Strait of Hormuz, which is the key to the Persian Gulf and through which most of the hydrocarbon exports of Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain pass[2]. 2] And lastly, because of the nuclear programme in which it has invested so many years.

The Iranian republic is based on the principles of Shia Islam, although there is great ethnic diversity in its society. It is therefore essential to take into account the great "strength of Iranian nationalism" in order to understand its politics. By appealing to its dominant position over other countries, the Iranian nationalist movement aims to influence public opinion. Nationalism has been building for more than 120 years, since the Tobacco Boycott of 1891[4] was a direct response to outside intervention and pressure, and today aims to achieve hegemony in the region. Iran's foreign and domestic policies are a clear expression of this movement[5].

Proxy armies (proxy armies)

War by proxy is a war model in which a country uses third parties to fight or influence a given territory, rather than engaging directly. As David Daoud points out, in Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen and Syria, 'Tehran has perfected the art of gradually conquering a country without replacing its flag'[6]. The Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard (IRGC) is directly involved in this task, militarily training or favouring the forces of other countries.

The GRI was born with the Islamic Revolution led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, in order to maintain the achievements of the movement[7]. 7] It is one of the main political and social actors in the country. It has a great capacity to influence national political debates and decisions. It is also the owner of numerous companies in the country, which guarantees it its own funding source and reinforces its character as an internal power. It is an independent body from the armed forces, and the appointment of its senior officers depends directly on the Leader of the Revolution. Among its objectives is the fight against imperialism, and it expressly commits itself to trying to rescue Jerusalem and return it to the Palestinians[8]. 8] Their importance is crucial to the regime, and any attack on these bodies represents a direct threat to the Iranian government.

Iran's relationship with the Muslim countries around it is marked by two main facts: on the one hand, its Shiite status; on the other, the pre-eminence it has achieved in the past in the region[10]. 10] Thanks to the fact that its external action is supported by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard, Iran has managed to establish strong links with political and religious groups throughout the Middle East. From there, Iran uses a variety of means to strengthen its influence in different countries. Firstly, by using soft power tools. Thus, among other actions, Iran has participated in the reconstruction of mosques and schools in countries such as Lebanon and Iraq[11]. 11] In Yemen, it has provided logistical and economic aid to the Houthi movement. In 2006, it was involved in the reconstruction of South Beirut.

However, the methods used by these forces go to other extremes, moving towards more intrusive(hard power) mechanisms. For example, following the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Iran has established a foothold there over three decades, with Hezbollah as a proxy, taking advantage of complaints about the disenfranchisement of the Shia community. This course of action has allowed Tehran to promote its Islamic Revolution abroad[12].

In Iraq, the GRI sought to destabilise Iraq internally by supporting Shiite factions such as the Badr organisation during the Iranian-Iraqi war of the 1980s. Iran, on the other hand, involved the GRI in Saddam Hussein's uprising in the early 1990s. Through this subject of influences and embodying the proxy army paradigm, Iran has been establishing very direct influence over these places. Even in Syria, this elite Iranian corps is highly influential, supporting the Assad government and the Shia militias fighting alongside it.

For its part, Saudi Arabia accuses Iran and its Guard of supplying arms in Yemen to the Houthis (a movement that defends the Shiite minority), generating a major escalation of tension between the two countries.

The GRI has thus established itself as one of the most important factors in the Middle East landscape, driving the struggle between two opposing camps. However, it is not the only one. In this way, we find a "cold war" scenario, which ends up transcending and becoming an international focus. On the one hand, Iran, supported by powers such as Russia and China. On the other, Saudi Arabia, supported by the US. This conflict is developing, to a large extent, in an unconventional manner, through proxy armies such as Hezbollah and the Shiite militias in Iraq, Syria and Yemen[14].

Causes of confrontation

Tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran have spread throughout the Middle East (and beyond), creating two distinct camps in the Middle East, both seeking to claim hegemony in the region.

To interpret this scenario and better understand civil service examination it is important, first of all, to distinguish between two opposing ideological currents: Shiism and Sunnism (Wahhabism). Wahhabism is an extreme right-wing Muslim religious tendency of the Sunni branch, which is today the majority religion in Saudi Arabia. Shi'ism, as previously mentioned, is the current on which the Republic of Iran is based. However, as we shall see, the struggle between Iran and Saudi Arabia is political, not religious; it is based more on ambition for power than on religion.

Secondly, the control of oil trafficking is another cause of this rivalry. To understand this reason, it is worth bearing in mind the strategic position that the countries of the Middle East play on the global map, as they are home to the world's largest hydrocarbon reserves. issue A large number of contemporary struggles are in fact due to the interference of the major powers in the region, seeking to play a role in these territories. Thus, for example, the 1916 Sykes-Picot[15] agreement for the distribution of European influences continues to condition current events. Both Saudi Arabia and Iran, as we have said, have a special role to play in these confrontations, for the reasons described above.

Under these considerations, it is important to note, thirdly, the involvement in these tensions of external powers such as the United States.

The effects of the Arab Spring have weakened many countries in the region. Not so Saudi Arabia and Iran, which in recent decades have sought to consolidate their position as regional powers, largely thanks to the support provided by their oil production and large oil reserves. The differences between the two countries are reflected in the way they seek to shape the region and the different interests they pursue. In addition to the ethnic differences between Iran (Persians) and Saudi Arabia (Arabs), their alignment on the international stage is also opposite. Wahhabism presents itself as anti-American, but the Saudi government is aware of its need for US support, and the two countries have a reciprocal convenience, with oil as a basis. The same is not true of Iran.

Iran and the US were close allies until 1979. The Islamic Revolution changed everything and since then, with the hostage crisis at the US embassy in Tehran as a particularly dramatic initial moment, tensions between the two countries have been frequent. The diplomatic confrontation has become acute again with President Donald Trump's decision to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed in 2015 for Iran's nuclear non-proliferation, with the consequent resumption of economic sanctions against Iran. Moreover, in April 2019, the United States placed the Revolutionary Guard on its list of terrorist organisations[16], holding Iran responsible for financing and promote terrorism as a government tool [17].

On the one side, then, are the Saudis, supported by the US and, within the region, by the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Bahrain and Israel. On the other side are Iran and its allies in Palestine, Lebanon (pro-Shiite side) and recently Qatar, to which Syria and Iraq (Shiite militias) could be added. Tensions increased after the death of Qasem Soleimani in January 2020. In the latter camp we could highlight the international support of China and Russia, but little by little we can observe a distancing of relations between Iran and Russia.

When talking about the struggle for hegemony in the control of oil trafficking, it is essential to mention the Strait of Hormuz, the crucial geographical point of this conflict, where both powers are directly confronted. This strait is a strategic area located between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. Forty percent of the world's oil passes through it[18]. Control of these waters is obviously decisive in the confrontation between Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as for any of the members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries of the Middle East (OPEC) in the region: Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait.

One of the objectives of Washington's economic sanctions against Iran is to reduce its exports in order to favour Saudi Arabia, its largest regional ally. To this end, the US Fifth Fleet, based in Bahrain, is tasked with protecting commercial shipping at area.

The Strait of Hormuz "is the escape valve Iran uses to relieve pressure from outside the Gulf" [19]. From here, Iran tries to react to economic sanctions imposed by the US and other powers; it is this that gives it a greater voice on the international stage, as it has the ability to block the strategic passage. Recently there have been attacks on oil tankers from Saudi Arabia and other countries[20], which causes great economic and military destabilisation with each new episode[21].

At final, the skill between Iran and Saudi Arabia has an effect not only regionally but also globally. The conflicts that could erupt in this area are increasingly reminiscent of a familiar Cold War, both in terms of the methods on the battlefront (and the incidence of proxy armies on this front), and the attention it requires for the rest of the world, which depends on this result, perhaps more than it is aware of.

Conclusions

For several years now, a regional confrontation has been building up that also involves the major powers. This struggle transcends the borders of the Middle East, similar to the status unleashed during the Cold War. Its main actors are the proxy armies, which are driving struggles through non-state actors and unconventional methods of warfare, constantly destabilising relations between states, as well as within states themselves.

To avoid the fighting in Hormuz, countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have tried to transport oil in other ways, for example by building pipelines. This tap is held by Syria, through which the pipelines must pass in order to reach Europe). In the end, the Syrian war can be seen from many perspectives, but there is no doubt that one of the reasons for the meddling of extra-regional powers is the economic interest in the Syrian coastline.

From 2015 to the present, Yemen's civil war has been raging in silence. At stake are strategic issues such as control of the Mandeb Strait. Behind this terrible war against the Houthis(proxies), there is a latent fear that the Houthis will take control of access to the Red Sea. In this sea and close to the strait is Djibouti, where the major powers have installed instructions to better control the area.

The most affected power is Iran, which sees its Economics weakened by constant economic sanctions. The status affects a population oppressed both by its own government and by international pressure. The government itself ends up misinforming society, leading to a great mistrust of the authorities. This leads to growing political instability, which manifests itself in frequent protests.

The regime has publicised these demonstrations as protests against US actions, such as the assassination of General Soleimani, without mentioning that many of these revolts are due to widespread civilian discontent over the serious measures taken by Ayatollah Khamenei, who is more focused on pursuing hegemony in the region than on resolving internal problems.

Thus, it is often difficult for the majority of the world to realise the implications of these confrontations. Indeed, the use of proxy armies should not distract us from the fact of the real involvement of major powers in the West and East (in true Cold War fashion). Nor should the alleged motives for keeping these fronts open distract us from the true incidence of what is really at stake: none other than the global Economics .

[1] El nuevo mapa de los gigantes globales del petróleo y el gas, David Page, Expansión.com, 26 June 2013. available en

[2] The four points core topic through which oil travels: The Strait of Hormuz, Iran's "weapon", 30 July 2018. available en

[3] In November 2013, China, Russia, France, the United Kingdom and the United States (P5) and Iran signed the Joint Plan of Action (JPOA). This was an initial agreement on Iran's nuclear programme, which was the subject of several negotiations leading to a final pact, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed in 2015, to which the European Union adhered.

[4] The Tobacco Boycott was the first movement against a concrete action of the state; it was not a revolution in the strict sense of the word, but a strong nationalism was rooted in it. It came about because of the tobacco monopoly law granted to the British in 1890. More information in: "El veto al tabaco", Joaquín Rodríguez Vargas, Professor at the Complutense University of Madrid.

[5] notebook de estrategia 137, Ministerio de Defensa: Iran, potencia emergente en Oriente Medio. Implications for Mediterranean stability. high school Español de programs of study Estratégicos, July 2007. available en

[6] Meet the Proxies: How Iran Spreads Its Empire through Terrorist Militias,The Tower Magazine, March 2015. available en

[7] article 150 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran expressly states this.

[8] Tensions between Iran and the United States: causes and strategies, Kamran Vahed, high school Spanish Strategic programs of study , November 2019. available en, p. 5.

[9] One of the six sections of the GRI is the "Quds" Force (commanded by Qasem Soleimani), which specialises in conventional warfare and military intelligence operations. It also manager to conduct extraterritorial interventions.

[11] Iran-US tensions: causes and strategies, Kamran Vahed, high school Spanish Strategic programs of study , November 2019. available en

[13] Yemen: the battle between Saudi Arabia and Iran for influence in the region, Kim Amor, 2019, El Periódico. available en

[14] Iran versus Saudi Arabia, an imminent war?, Juan José Sánchez Arreseigor, IEEE, 2016. available en

[15] The Sykes-Picot agreement was a secret pact between Britain and France during World War I (1916) in which, with the consent of (pre-Soviet) Russia, the two powers divided up the conquered areas of the Ottoman Empire after the Great War.

[17] Statement from the President on the Designation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, Foreign Policy, April 2019. available en

[18] The Strait of Hormuz, the world's main oil artery, Euronews (data checked with Vortexa), 14 June 2019. available en

![Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia]. Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-isi-blog.jpg)

Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia].

ESSAY / Manuel Lamela

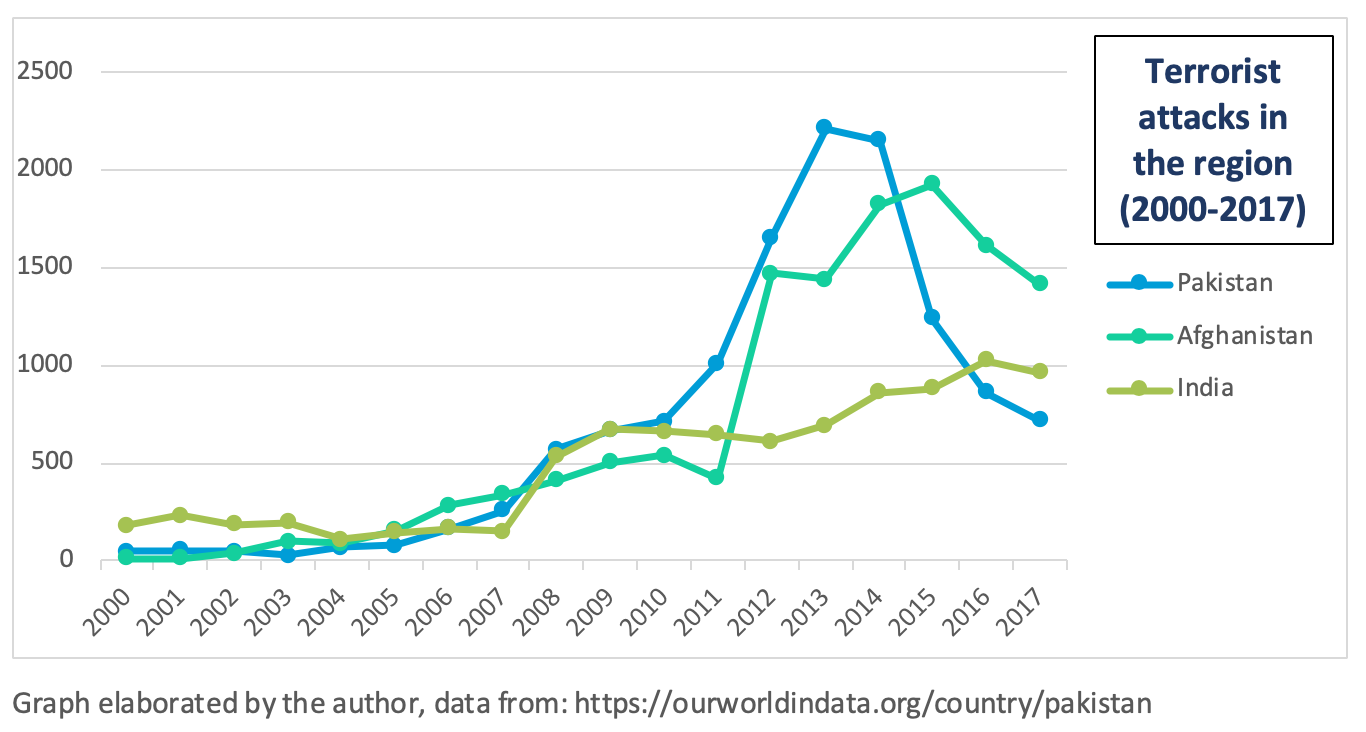

Jihadism continues to be one of the main threats Pakistan faces. Its impact on Pakistani society at the political, economic and social levels is evident, it continues to be the source of greatest uncertainty, which acts as a barrier to any company that is interested in investing in the Asian country. Although the situation concerning terrorist attacks on national soil has improved, jihadism is an endemic problem in the region and medium-term prospects are not positive. The atmosphere of extreme volatility and insistence that is breathed does not help in generating confidence. If we add to this the general idea that Pakistan's institutions are not very strong due to their close links with certain radical groups, the result is a not very optimistic scenario. In this essay, we will deal with the current situation of jihadism in Pakistan, offering a multidisciplinary approach that helps to situate itself in the complicated reality that the country is experiencing.

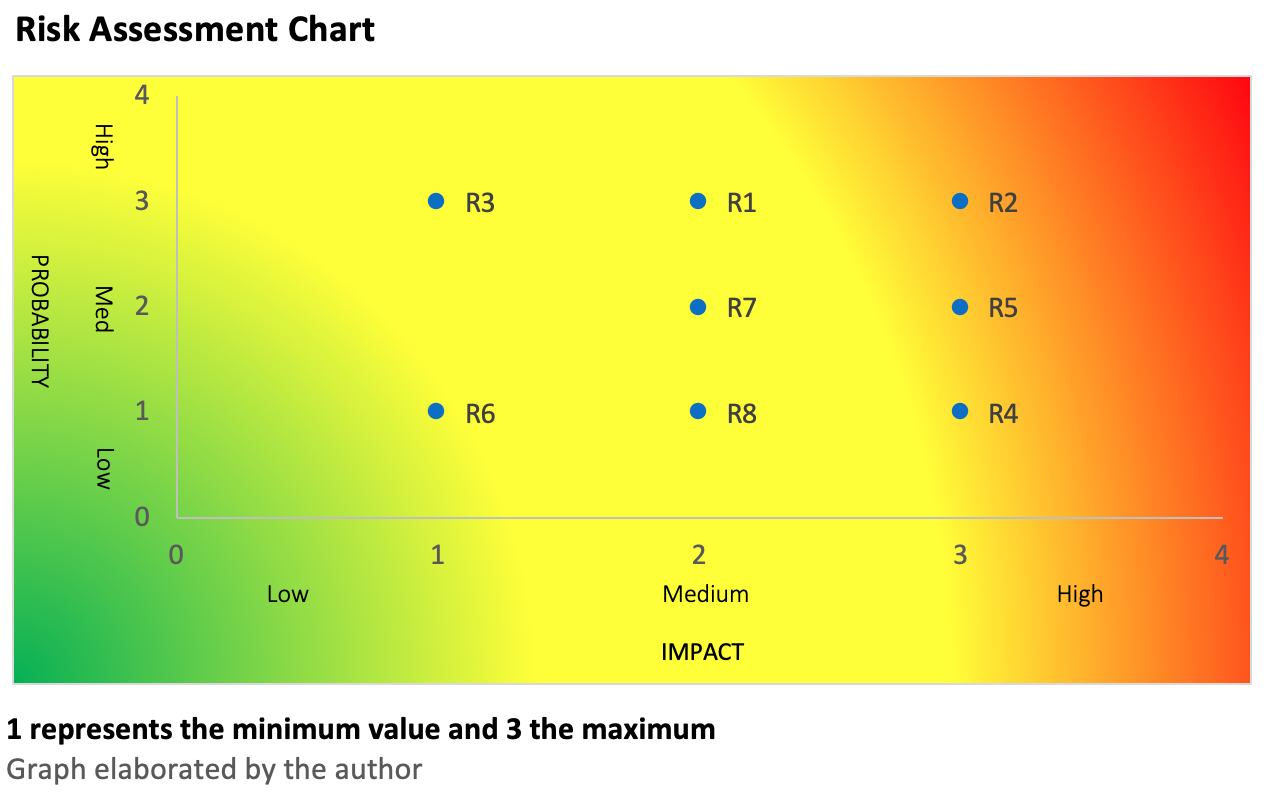

1. Jihadism in the region, a risk assessment

Through this graph, we will analyze the probability and impact of various risk factors concerning jihadist activity in the region. All factors refer to hypothetical situations that may develop in the short or medium term. The increase in jihadist activity in the region will depend on how many of these predictions are fulfilled.

Risk Factors:

A1: US-Taliban treaty fails, creating more instability in the region. If the United States is not able to make a proper exit from Afghanistan, we may find ourselves in a similar situation to that experienced during the 1990s. Such a scenario will once again plunge the region into a fierce civil war between government forces and Taliban groups. The proposed scenario becomes increasingly plausible if we look at the recent American actions regarding foreign policy.

A2: Pakistan two-head strategy facing terrorism collapse. Pakistan's strategy in dealing with jihadism is extremely risky, it's collapse would lead to a schism in the way the Asian state deals with its most immediate challenges. The chances of this strategy failing in the medium term are considerably high due to its structure, which makes it unsustainable over the time.

R3: Violations of the LoC by the two sides in the conflict. Given the frequency with which these events occur, their impact is residual, but it must be taken into account that it in an environment of high tension and other factors, continuous violations of the LoC may be the spark that leads to an increase in terrorist attacks in the region.

R4: Agreement between the afghan Taliban and the government. Despite the recent agreement between Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Albduallah, it seems unlikely that he will be able to reach a lasting settlement with the Taliban, given the latter's pretensions. If it is true that if it happens, the agreement will have a great impact that will even transcend Afghan borders.

R5: Afghan Taliban make a coup d'état to the afghan government. In relation to the previous point, despite the pact between the government and the opposition, it seems likely that instability will continue to exist in the country, so a coup attempt by the Taliban seems more likely than a peaceful solution in the medium or long term

R6: U.S. Democrat party wins the 2020 elections. Broadly speaking, both Republican and Democratic parties are betting on focusing their efforts on containing the growth of their great rival, China.

R7: U.S. withdraw its troops from Afghanistan regarding the result of the peace process. This is closely related to the previous point as it responds to a basic geopolitical issue.

R8: New agreement between India and Pakistan regarding the LoC. If produced, this would bring both states closer together and help reduce jihadist attacks in the Kashmir region. However, if we look at recent events, such a possibility seems distant at present.

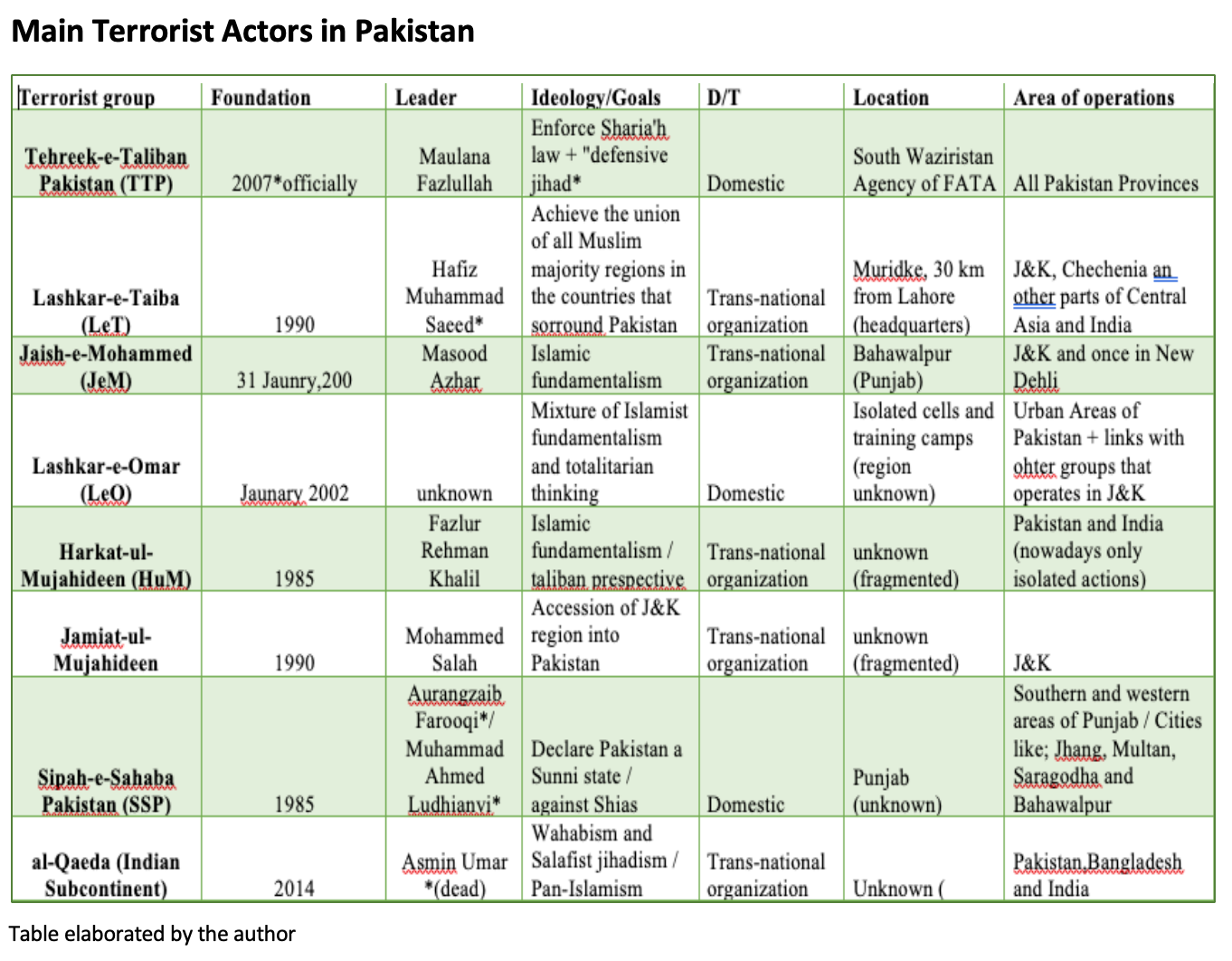

2. The ties between the ISI and the Taliban and other radical groups

Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) has been accused on many occasions of being closely linked to various radical groups; for example, they have recently been involved with the radicalization of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh[1]. Although Islamabad continues strongly denying such accusations, reality shows us that cooperation between the ISI and various terrorist organisations has been fundamental to their proliferation and settlement both on national territory and in the neighbouring states of India and Afghanistan. The West has not been able to fully understand the nature of this relationship and its link to terrorism. The various complaints to the ISI have been loaded with different arguments of different kinds, lacking in unity and coherence. Unlike popular opinion, this analysis will point to the confused and undefined Pakistani nationalism as the main cause of this close relationship.

The Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence, together with the Intelligence Bureau and the Military Intelligence, constitute the intelligence services of the Pakistani State, the most important of which is the ISI. ISI can be described as the intellectual core and center of gravity of the army. Its broad functions are the protection of Pakistan's national security and the promotion and defense of Pakistan's interests abroad. Despite the image created around the ISI, in general terms its activities and functions are based on the same "values" as other intelligence agencies such as the MI6, the CIA, etc. They all operate under the common ideal of protecting national interests, the essential foundation of intelligence centers without which they are worthless. We must rationalize their actions on the ground, move away from inquisitive accusations and try to observe what are the ideals that move the group, their connection with the government of Islamabad and the Pakistani society in general.

2.1. The Afghan Taliban

To understand the idiosyncrasy of the ISI we must go back to the war in Afghanistan[2], it is from this moment that the center begins to build an image of itself, independent of the rest of the armed forces. From the ISI we can see the victory of the Mujahideen on Afghan territory as their own, a great achievement that shapes their thinking and vision. But this understanding does not emerge in isolation and independently, as most Pakistani society views the Afghan Taliban as legitimate warriors and defenders of an honourable cause[3]. The Mujahideen victory over the USSR was a real turning point in Pakistani history, the foundation of modern Pakistani nationalism begins from this point. The year 1989 gave rise to a social catharsis from which the ISI was not excluded.

Along with this ideological component, it is also important to highlight the strategic aspect; we are dealing with a question of nationalism, of defending patriotic interests. Since the emergence of the Taliban, Pakistan has not hesitated to support them for major strategic reasons, as there has always been a fear that an unstable Afghanistan would end up being controlled directly or indirectly by India, an encirclement strategy[4]. Faced with this dangerous scenario, the Taliban are Islamabad's only asset on the ground. It is for this reason, and not only for religious commitment, that this bond is produced, although over time it is strengthened and expanded. Therefore, at first, it is Pakistani nationalism and its foreign interests that are the cause of this situation, it seeks to influence neighbouring Afghanistan to make the situation as beneficial as possible for Pakistan. Later on, when we discuss the situation of the Taliban on the national territory, we will address the issue of Pakistani nationalism and how its weak construction causes great problems for the state itself. But on Afghan territory, from what has been explained above, we can conclude that this relationship will continue shortly, it does not seem likely that this will change unless there are great changes of impossible prediction. The ISI will continue to have a significant influence on these groups and will continue its covert operations to promote and defend the Taliban, although it should be noted that the peace treaty between the Taliban and the US[5] is an important factor to take into account, this issue will be developed once the situation of the Taliban at the internal level is explained.

2.2. The Pakistani Taliban (Al-Qaeda[6] and the TTP)

The Taliban groups operating in Pakistan are an extension of those operating in neighbouring Afghanistan. They belong to the same terrorist network and seek similar objectives, differentiated only by the place of action. Despite this obvious similarity, from Islamabad and increasingly from the whole of Pakistani society, the two groups are observed in a completely different way. On the one hand, as we said earlier, for most Pakistanis, the Afghan Taliban are fighting a legitimate and just war, that of liberating the region from foreign rule. However, groups operating in Pakistan are considered enemies of the state and the people. Although there was some support among the popular classes, especially in the Pashtun regions, this support has gradually been lost due to the multitude of atrocities against the civilian population that have recently been committed. The attack carried out by the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)[7] in the Army Public School in Peshawar in the year 2014 generated a great stir in society, turning it against these radical groups. This duality marks Pakistan's strategy in dealing with terrorism both globally and internationally. While acting as an accomplice and protector of these groups in Afghanistan, he pursues his counterparts on their territory. We have to say that the operations carried out by the armed forces have been effective, especially the Zarb-e-Azb operation carried out in 2014 in North Waziristan, where the ISI played a fundamental role in identifying and classifying the different objectives. The position of the TTP in the region has been decimated, leaving it quite weakened. As can be seen in this scenario, there is no support at the institutional level from the ISI[8], as they are involved in the fight against these radical organisations. However, on an individual level if these informal links appear. This informal network is favoured by the tribal character of Pakistani society, it can appear in different forms but often draw on ties of Kinship, friendship or social obligation[9]. Due to the nature of this type of relationship, it is impossible to know to what extent the ISI's activity is conditioned and how many of its members are linked to Taliban groups. However, we would like to point out that these unions are informal and individual and not institutional, which provides a certain degree of security and control, at least for the time being, the situation may vary greatly due to the lack of transparency.

2.3. ISI and the radical groups that operate in Kashmir

Another part of the board is made up of the radical groups that focus their terrorist attention on the conflict with India over control of Kashmir, the most important of which are: Lashkar-e-Taiba (Let) and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM). Both groups have committed real atrocities over the past decades, the most notorious being the one committed by LeT in the Indian city of Mumbai in 2008. There are numerous testimonies, in particular, that of the American citizen David Haedy, which point to the cooperation of the ISI in carrying out the aforementioned attack.[10]

Recently, Hafiz Saeed, founder of Let and intellectual planner of the bloody attack, was arrested. The news generated some turmoil both locally and internationally and opened the discussion as to whether Pakistan had finally decided to act against the radical groups operating in Kashmir. We are once again faced with a complex situation, although the arrest shows a certain amount of willpower, it is no more than a way of making up for the situation and relaxing international pressure. The above coincides with the FATF's[11] assessment of Pakistan's status within the institution, which is of great importance for the short-term future of the country's economy. Beyond rhetoric, there is no convincing evidence that suggests that Pakistan has made a move against those groups. The link and support provided by the ISI in this situation are again closely linked to strategic and ideological issues. Since its foundation, Pakistani foreign policy has revolved around India[12], as we saw on the Afghan stage. Pakistani nationalism is based on the maxim that India and the Hindus are the greatest threat to the future of the state. Given the significance of the conflict for Pakistani society, there has been no hesitation in using radical groups to gain advantages on the ground. From Pakistan perspective, it is considered that this group of terrorists are an essential asset when it comes to putting pressure on India and avoiding the complete loss of the territory, they are used as a negotiating tool and a brake on Indian interests in the region.