Read

What is it about the ancient world?

Javier Andreu, professor of History and director of Diploma in Archaeology,

reflects on the weight of Roman history in our culture.

Why is Rome so attractive to us, and is its history inexhaustible?

Let's start with the latest literary successes: they seem to echo a veritable renaissance of Roman history.

a veritable renaissance of the Classical Humanities today

The best-selling book in Spain during the two long months of confinement due to the pandemic has been El infinito en un junco: la invención de los libros en el mundo antiguo (The Infinite in a Reed: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World), which has won, in fact, the Ojo Crítico de Narrativa. Irene Vallejo which has, in fact, won the award Ojo Crítico de Narrativa. The second is Y Julia retó a los dioses (And Julia Challenged the Gods), by Santiago Posteguilloanother submission in the series on Julia Domna that the recent award Planeta has given us.

These successes are not the only ones. The delightful essay of the media-accessible Mary Beard SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. Or other non-fiction titles such as A Year in Ancient Rome: The Daily Life of the Romans through their Calendar, by Néstor Marqués Latin lovers, by Emilio del Río; A day in Pompeii, by Fernando Lilloand many more... All of them are still doing very well in the market. And they are not even historical novels. But the Roman world and its perennial topicality is at the heart of them all.

There are many great books to be found in the historical novel. Hadrian's Memoirs by Marguerite Yourcenarfor example, or the famous I, Claudius of Robert Graves are already classics that are recognised as source inspiration for the greats of the genre and for screenwriters.

The peplum film genre (the mythical "Roman" films), in fact, remains source of success. We are still thrilled by William Wilder's reveries as he brought to life Prince Ben-Hur and the terrible Messala. Or with the adventures of the Hispanic Maximus Meridius who challenged, in Gladiator, the emperor Commodus, perhaps the last emperor of the "golden age" of Rome. Ben-Hur y GladiatorIncidentally, they are two of the most awarded blockbusters in the history of cinema.

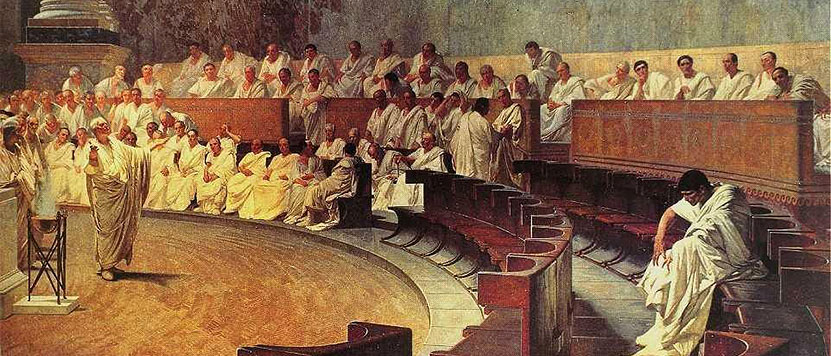

What is it about the ancient world, and in particular the Roman world, that has such a particular fascination? What first comes to mind is the strength of some of its characters. We can often see ourselves reflected in them and find models, and anti-models, of behaviour. But that is not all. In historical narrative we find answers to many problems that would seem new to us today. Rome attracts us because of its topicality, its relevance, its eternity.

What is it about the ancient world, and in particular the Roman world, that has such a particular fascination? What first comes to mind is the strength of some of its characters. We can often see ourselves reflected in them and find models, and anti-models, of behaviour. But that is not all. In historical narrative we find answers to many problems that would seem new to us today. Rome attracts us because of its topicality, its relevance, its eternity.

Just a few months ago, Santiago Posteguillo reminded the students of Degree in Literature and Creative Writing and Diploma in Archaeology at School of Philosophy and Lettersthat "we are Rome", he said, "Rome is relevant to see where we come from". Undoubtedly, we have a lot left of Rome, and Santiago Posteguillo was certainly not wrong in aligning himself with the old statement by Montanelli in the prologue to his History of Rome (1957):

"what makes the History of Rome great is not that it was made by men

that it was made by men different from us

but that it was made by men like us".

We look at Rome and see ourselves. We read the Roman historians and feel that their judgements of the times would also apply to our own times. The knowledge of how Rome ruled the world and how that ruling was perceived by other peoples would also be valid for judging the lights and shadows of our own time. From framework Aurelius we know that the problems that shake the contemporary world are neither new nor surprising (without detracting from their importance, of course).

The great Greco-Roman historians who, in the times of the Republic (Polybius) or the Principate (Titus Livy), undertook the business task of dealing with the History of Rome, already perceived the power of this civilisation as a historical object.

PolybiusFor example, he said that the History of Rome, as early as the second century BC, was endowed with "a known beginning, a definite duration and a notorious result ".. This made it attractive, tangible and suggestive for the researcher. Using very modern historiographical concepts, the historian of Megalopolis, the great defender of the benefits of Roman imperialism, stated that Roman civilisation was the first to make history "organic".

Under Roman rule, "The facts of Italy and Africa are intertwined with those of Asia and Greece and all begin to refer to a single purpose".that of the spread of a way of life "in private life and on the public administration". A way of life to which, to a large extent, we are heirs, and which was "enviable to contemporaries and unsurpassed by the men of the future".. This is also the reason for its undeniable appeal, which will have powerfully seduced us all at one time or another.

However, in addition to their limited time frame, the events of Roman history are always open to discussion. This makes the classical world, and the Roman period in particular, an adventure for the knowledge. The reality of Roman history, the "knowledge of past events". was already under discussion in the Roman period itself, when, as he said Titus Livy:

"New historians are continually appearing, some claiming that they will

claim, some of them, that they are going to provide more consistent documentation on the

more consistent documentation in the field of facts, others

that their style will surpass the slovenliness of the old authors".

old authors".

As I usually explain to my students at the beginning of the "Classical World" subject , facing a History that is constantly under construction and of which we know a lot (but of which we know even more) is a school. "which enables us to endure with endurance the changes of fortune". (Polybius, in praise of History). Moreover, it opens before us a pathway in which each finding proves to be decisive in order to know in more detail "What was the life, what were the customs, by what men, by what policy in civil and military matters was the Empire of Rome created and enlarged? (Titus Livy).

Each new reading of a classical author, each new light shed by a modern historian or a revision by an ancient scholar, together with the findings of archaeological excavations and the epigraphic and papyrological programs of study are an inexhaustible source of knowledge. It is an adventure that attracts legions of students and readers alike. On final, we are witnessing a real renaissance of the Classical Humanities . The data sales figures with which we began this reflection echo this.

The intense research activity carried out in so many universities and international centres of research on the Roman period, and its transfer through the channels of knowledge dissemination, are the basis of the constancy (and never decadence) of our fascination. Supported by fragmentary but always eloquent sources, we move to that "infinite" that Irene Vallejo claims in the book with which we opened our article.

This "infinity" lives on in our history. We can even say that we are still Rome, so much of it remains (and so much remains to be discovered)! Thanks precisely to the research, this vivacity of the Roman world is increasing, and its central centuries are increasingly discovered as a changing, shocking, irresistible, fascinating, fabulous, eternal period.

Titus Livy himself mentioned in the preface to his Roman History that history is constantly being rewritten. This was recently recalled by the aforementioned Mary Beard when, in the opening lines of her SPQR, she states:

"Rome's history is constantly being rewritten and has always been so

and always has been ... In a way, we know

today more about ancient Rome than the Romans themselves.

Romans themselves. The History of Rome is still at development".

Each new reflection, each new approach to the past and each new finding or piece of evidence transforms and reactivates our perception of the past. Hence, our certainty that the study of the History of Rome remains a work for all time and that it continues, in a rapturous way, to fascinate immense numbers of researchers, writers, journalists... Thus, it is not surprising that more and more students find in Rome, in its characters and vicissitudes, in its greatness and its misery, an authentic and constant source of inspiration source .

Irene VallejoThe infinity in a reed: the invention of books in the ancient world. BUY.

Santiago Posteguillo And Julia challenged the gods. BUY.

Mary Beard SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. BUY.

Néstor Marqués A year in Ancient Rome: the daily life of the Romans through their calendar. BUY.

Emilio del Río Latin lovers. BUY.

Fernando Lillo A day in Pompeii. BUY.

Marguerite Yourcenar Memoirs of Hadrian. BUY.

Robert Graves I, Claudius. BUY.

Indro Montanelli, History of Rome. BUY.

Titus Livy Roman History. BUY.

Polybius of Megalopolis History of Rome. BUY.