Give your opinion

The danger of philosophising

Víctor Maspons, student of the 1st year of Philosophy and Law, warns about

some of the dangers involved in the difficult search for truth.

Excessive abstractions, the gentrification of reason and a distancing from reality.

and the distancing from reality. As we can see, it is all very topical.

The Philosophy is born of wonder. We are fascinated by reality and we try to understand it, and this is what Philosophy does. And the deeper we go into it, the greater our capacity to philosophise. It is clear that reality is intelligible, for if it were not, why do we continue to wonder about it, and why do we succeed in understanding it in various fields? If the search for truth had yielded absolutely nothing result, we would have given up, and wonder would have died. However, the results have been enormously positive, and the history of human thought and progress attests to this. Nevertheless, this search for truth has certain dangers, which have had dire consequences in history. There are three main ones: excessively logical abstractions, the gentrification of reason and detachment from reality. All three are interrelated, and a wander into one can lead to the others.

The first of these holds that one, in abstracting, has to be particularly logical and rational (Stebbing, 1939). We think that everything is black or white and we forget about the nuances, about those concepts that are not quite delimited. We think that everything is clearly defined in the mind, which is not true, and we apply these concepts to reality, which is much richer than it seems. For example, in the field of ethics, we can make the mistake of saying that if something is wrong then it must be illegal. We link the reprehensible with the unlawful and the plausible with the lawful, and it is true that they are related, but they are not fully identified. Of course, there are very bad actions that must be illegal and very good ones that must be legal, but there are others that lie somewhere in between. They are not as harmful, but their over-regulation can cause greater harm. For example, drinking alcohol to excess may be wrong, but social realities must be taken into account when deciding whether to legalise or criminalise it. Otherwise, what happened in the 20th century in the United States, and the consequences of "Prohibition", can happen. Citizens continued to consume alcohol, only this time they were supplied by the black market, run by the mafia. We can see it in the cinema classics, such as The Godfather o GoodfellasThe murders rained down, corruption and power struggles broke out among the mafias.

We link the reprehensible with the unlawful and the plausible with the lawful.

with the lawful, and it is true that they are related,

but they are not fully identified.

Secondly, we must beware of the gentrification of our reason. According to classical thought, reason is a determined use of intelligence, which allows us to understand contingent reality. We can always know new things and keep learning, there is no limit: reason has infinite power (hence its spiritual character). And yet, although it has inexhaustible capacities, it cannot know everything and its knowledge does not arise from itself, but from contingent reality. Clearly, this can be forgotten and we can come to believe that reason is self-sufficient. We can come to have unlimited faith in our aptitude to reason, without taking into account its fallibility and dependence on the data provided by reality. This is the gentrification of reason.

During the Modern Age, with the Enlightenment, man was characterised by an extreme reliance on reason, causing serious social problems. The History of Law is a good example of this: between the 18th and 19th centuries, the revolutionary bourgeoisie overthrew the pillars of the Ancien Régime and established itself in power. At the same time, philosophers and jurists emerged who, with the strong support of the bourgeoisie, tried to create a new law based solely on "Man" in the abstract. A concept of man that does not take into account social, economic or political reality, but only the universal nature of the human being. In other words, reason alone was to draw general principles about man and then create a law based on them. This ideal led to the failure of codification, because reason alone could not encompass the whole of reality. It constantly surpassed written law: the law promulgated equality, but society overflowed with inequalities (Caroni, 1993). Man cannot be thought of only in the abstract, he is real. And without that reality he ceases to be man. The gentrification of reason leads us to think in an idealistic, rigid, inhuman way.

The philosopher is not only there to contemplate ideas,

but to bring others closer to them, to educate in truth.

in the truth.

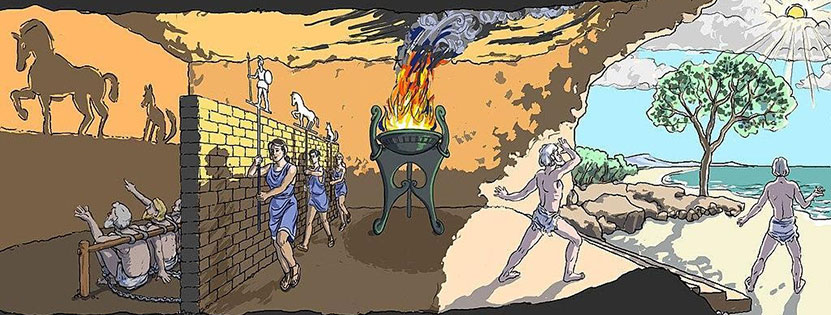

Finally, the two previous risks lead to a third, which is, in itself, contradictory: distancing oneself from reality. One philosophises in order to understand reality in its foundations, but, by falling in love with his reason, he distances himself from the object and the cause of Philosophy. He ends up philosophising for the sake of philosophising, losing sight of its purpose. PlatoThe philosopher, in the fourth century B.C., was the first to detect this danger. In fact, it is ironic, because Plato argued that the true reality is not the one in which we find ourselves, but the intelligible world of Ideas. Thus, one philosophises in order to move progressively away from the body and towards the Ideas. However, Plato does not argue for our complete independence from corporeal reality. Rather, he proposes a distancing at the epistemological level (from knowledge), not at the ethical level. This is what the Allegory of the Cave is about. When the man leaves the cave and contemplates the Ideas, he decides to return to get the rest out of the cave, even if his return means death. The philosopher is not only there to contemplate the ideas, but to bring others closer to them, to educate in truth. Plato realised this from the beginning. In his thought there is a clear connection between ontology and epistemology with ethics and politics through Education (Vallejo, 2017). In final, man, enlightened by the eternal Ideas, must educate others so that his earthly life is truly good.

Certainly, there is great danger in philosophising, but this does not mean that we should desist from understanding reality. Let us philosophise in the spirit of Socrates, who was aware of his ignorance and that his reasoning could fail. Even if we are wrong, let us not give up the search for truth. Let us never lose our capacity for wonder.

An Illustration of The Allegory of the Cave, from Plato's Republic, 2018.

By 4edges (cc),

Wiki

bibliography

L. Susan Stebbing Thinking to Some Purpose (Hardmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1939). READ online or download from Internet Archive library.

Ruth Barcan Marcus Moral Dilemmas and Consistency", The Journal of Philosophy 77/3 (1980). READ in JSTOR.

Pio Caroni Lessons in the history of codification, 2013. READ.

Vallejo and Vigo, Greek philosophers: from the sophists to Aristotle (2017). BUY.

PlatoThe Republic, books VI, VII. BUY.