Give your opinion

HOW NICE, WHAT A BORE!

(On Joseph Brodsky's In Praise of Boredom )

|

|

Boredom does not enjoy much prestige today. Exciting", "fun", "exciting", "exciting", rough antonyms of "boring", are the adjectives we use when we want to praise something. Can we imagine a travel agency inviting us to a Wayside Cross in the Bahamas with the argument that it guarantees we will be bored, otherwise we will get our money back? Can we imagine a bored gentleman in his deckchair, looking at the camera: "Be bored with us, take advantage of our special offer, call now"? And yet it is obvious that boredom is only the flip side of a great achievement: that which only begins when the most peremptory needs are not only satisfied but assured. It is inconceivable that our Cro-Magnon ancestor, busy as he was with hunting, dodging vermin, getting a good fire, etc., would have been bored for long. Boredom begins with that question- "What now?" - that arises within us when we have procured the essentials.

What happens when the little lexicographer in all of us turns to the DRAE? It finds a few surprises. Of course, boredom is "weariness, weariness, tediousness, boredom, caused by displeasure or annoyance, or by not having something to distract and amuse". Nothing that we would not have foreseen in the first place. However, if we turn to the word "bored" we find that it comes from the Latin abhorrere, which means "to tire, annoy or annoy", which was formerly used to refer to the rejection of their offspring by some animals and which in fact in one of its meanings is synonymous with "to abhor". And if instead of etymology we turn to thymology - that fanciful game with the origin of words that runs through the most unpredictable twists and turns - we soon conclude that "aburrir" comes from "burro", and that is why we advise the child who says he is bored not to behave like one and to put a bit of wit into his hours; or we notice that gap in the language that forces us to call a speaker who wears us out "boring", when in fact we should consider him "boring", since one can very well bore others and at the same time be very entertaining.

I'M BORED!

BUY A DONKEY!

(The most famous scream of a funny hopelessness by now)

Of course, I doubt that the DRAE will pick up my proposal, but that does not mean that the Academy is completely oblivious to the issue. I remember a friend of mine starting a thesis on Philosophy about boredom a whopping twenty-five years ago. I don't think she finished it - perhaps she got bored along the way - but her attempt helped the rest of us to realise how important boredom is in our lives. And also in literature. It is enough to take a look at its various names, at the different categories it has given rise to: the acidia or acedia of the Castilian mystics, that "sluggishness", that aridity of the soul that finds no recreation in prayer; the "boredom" in which Wilde, who was familiar with the word "boredom", was the first to describe it. tedium vitae Wilde, who knew the cloth, was able to see where the path of excess leads; that of the French symbolists, the ennui of the French Symbolists, that radical disgust which inspires the world in "Au lecteur", the portico to Les fleurs du mal. Boredom would thus have a metaphysical scope, a distaste inseparable from existence itself that contains a whole amendment to Creation (although revealing its underbelly, as in the case of Baudelaire, can be great fun). To be bored is to abhor, it is to feel true horror. Hélas!

In fact, a brief survey of the entire literary cast yields a rather substantial duality. On the one hand, a Moravia who in his masterly The Boredom told us the story of a painter who decided one day to smash the canvas he was working on and never paint again; the boredom announced by degree scroll would be a substitute for Sartrian nausea, a difficulty in relating to what is around us; in other words, the perception of the blandness of everything, of the inability of the real to interest us; and when a figurative painter is no longer interested in reality, that's the end of the story. On the other hand, a Max Jacob who, in his Conseils à un jeun poète, encouraged his correspondent to be consciously bored, "because that is where ideas come from", he said; in order to be truly entertained, to be interested, to be passionate, it is necessary to distance oneself a little from the noise and to have some experience of calm, slowness, silence. In other words, there would be a negative and a positive boredom, one sterile and the other fertile. Boredom subject A and subject B.

To become truly entertained,

to be interested, to be passionate,

it is necessary to move away from the noise

and to have some experience of calm,

slowness, silence.

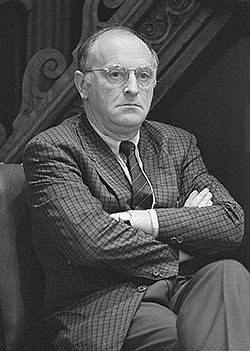

When you go back to In Praise of Boredomone of the prose works of that atrabiliary character named Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996)It is unavoidable to recall this duality of meanings. It is also necessary to note the insightfulness with which the Russian poet knew how to turn this dreaded boredom into an ally, a friend, a companion on the path of life (and of writing).. It is enough, for example, to note the provocative play of the title and the quotation at the head of the text, some verses from AudenAgainst the well-known "In Praise of Limestone", one of his master and friend's most celebrated pieces, against that eulogy of limestone which summed up the English poet's native landscape, Brodsky was proposing a praise of tedium. To tedium! A rupture of expectation, by means of provocation. That, the game that disrupts everything, was one of the richest resources against boredom, and the poet devoted himself to it conscientiously. But in order to disrupt everything, the everything must be there, in order to break the cliché, there must be such a cliché.

When you go back to In Praise of Boredomone of the prose works of that atrabiliary character named Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996)It is unavoidable to recall this duality of meanings. It is also necessary to note the insightfulness with which the Russian poet knew how to turn this dreaded boredom into an ally, a friend, a companion on the path of life (and of writing).. It is enough, for example, to note the provocative play of the title and the quotation at the head of the text, some verses from AudenAgainst the well-known "In Praise of Limestone", one of his master and friend's most celebrated pieces, against that eulogy of limestone which summed up the English poet's native landscape, Brodsky was proposing a praise of tedium. To tedium! A rupture of expectation, by means of provocation. That, the game that disrupts everything, was one of the richest resources against boredom, and the poet devoted himself to it conscientiously. But in order to disrupt everything, the everything must be there, in order to break the cliché, there must be such a cliché.

Another of the most succulent aspects of Brodsky's text is the fact that it comes from a speech at Darthmouth College, before a graduating class. Succulent because, if I may speculate, Brodsky's lecturing the new graduates on boredom presupposes the larger premise that they had not been lectured - or bored - during their programs of study. Or not enough, at least. A thesis that calls into question the nature and purpose of educational institutions as a whole (but which my students could no doubt argue about for hours).

In any case, what did Brodsky advise those young people before the university threw them out into the world? To gather strength, patience, because life - unlike art, which constantly flees from cliché - is fundamentally about repetition. " Boredom", he said, "is pure time, time in all its repetitive and redundant splendour" (so much so, as you can see, that Brodsky himself was tempted to adjectivise with redundancy). And what lesson did the speaker draw from this? That time is not unlimited, that we are finite and therefore insignificant; and that precisely this should invite us to consider the privilege of each minute, of each hour; that is, to shake boredom from us. A particularly sophisticated version of carpe diem, which a stubborn reader of Horace knew all too well. Sinking consciously into boredom served to hit rock bottom and get out of it.

Life - unlike art,

which constantly flees from cliché

consists fundamentally of repetition.

Any reader of Brodsky knows that he had all the authority one can have to speak of boredom, not least because he had swallowed his years in Arctic labour camps, Siberian expeditions and arrests at the hands of the KGB as a dissident. He knew how slowly time can pass in a cell or a dacha lost in the snow, but also the space that opens up for creativity. He knew how alienating and ubiquitous the propaganda of a regime could be, but also the inner freedom that is born in a soul when it is subtracted from those reiterative voices. There is, however, among his discarded proposals one to which I would like to draw attention: that of poverty. "St Francis escaped boredom through poverty," he says, "but today that doesn't seem very viable".

It seems to me that the news from 21st century Europe suggests that in the near future this feasibility will be quite literal, but I don't want to get bogged down in that question. As we have already seen, there are different types of boredom, and each era knows its own. The subject A - that of Moravia - was of existentialist lineage, derived from that vision of nothingness left behind by the horror of the first half of the twentieth century, and hence its negativity. The much more positive subject B -Jacob's- was of ascetic origin and serves to remind us that poverty means frugality. It is not surprising that good old Jacob exchanged wild parties and bohemia for his days in the monastery of Saint Benoît sur Loire: perhaps Montparnasse was too much fun, and ultimately more boring, than monastic life. Perhaps for real fun you have to spend some time in stillness and silence from time to time.

Our everyday situation therefore seems to be a variant of Stendhal's

a variant of Stendhal's malady in which the traveller

no longer needs to travel...

(and so far it can't either)

That, it seems to me, is the boredom we should fear today: an ennui that, like Moravia's, reveals an underlying nihilism, but this time a nihilism that paradoxically swims in abundance. The nihilism of totum revolutum, of the absence of hierarchy, of indifference, of anything goes, as long as there are huge quantities of nothing available, which is another name for triviality. Brodsky, who was writing just before the emergence of the age of Google and the internet, had not foreseen the avalanche of messages, that eme eses, wassaps, calls, shared photos, emails, links, likes, surfing the net, etc., that occupy our time. If the last meaning of "boredom" in the DRAE is "to suffer a state of mind produced by a lack of stimuli", our era has inaugurated a new kind of boredom, in the opposite sense. It is not the lack but the excess of stimuli that can be tedious today. And only that Franciscan frugality that Brodsky dismissed could save us from such a thing.

Of course, no one is proposing to eliminate source from these excesses, only to manage it better. "Get drunk! Of wine, of love, of poetry, of whatever, but get drunk," he demanded. Baudelaire. Well, contemporary sensibility, I'm afraid, has changed the poet's cry to "Get drunk! And we are well aware that, at this time of the year, after the Christmas festivities, the feeling of being drunk is a blunting of taste. It prevents any enthusiasm. When everything is brilliant, sparkling, hallucinating, nothing is. Our everyday status is therefore like a variant of the evil of Stendhal in which the traveller no longer needs to move, all he needs is an internet terminal to be overwhelmed... for a few seconds. And on to the next stimulus. A way of concealing boredom, not coping with it. The question is therefore no longer whether we are bored or not, but which subject boredom we prefer. In other words, how we fill the time that has been freed up from our occupations. To be bored better or worse, with more or less profit. Between the extreme of the unconscious alienation of being that of boredom and that of the asceticism of rigorous frugality, each one of us will have to choose. But I cannot go on any longer. For some time now, dear reader, you have been getting bored.

Ramón Casas,

Decadent young man

Readings mentioned

Joseph Brodsky In Praise of Boredom. DOWNLOAD (EN)

Alberto Moravia The tedium. BUY (Epub, Paper)

Max Jacob Conseils à un jeun poète. BUY (Epub, Paper)

Wystan Hugh AudenIn Praise of Limestone. READ.

HoratioOdes, Odes. BUY.

Why is my boredom such a bitch? The asceticism of confinement

Why is my boredom such a bitch? The asceticism of confinement