Think

TEN PÓLIN PHYLÁSEIN

|

|

A few days ago, our good friend Ángel Ventura, from department of Archaeology at the University of Córdoba, shared with us a phrase from a colleague of his, from the Universität Mainz, in Germany, very appropriate for the status that the whole of Europe, and particularly Spain, is going through: "how beautiful it is to write History but how difficult it is to live it". And it is true, with or without jokes, we are all aware that, due to the coronavirus crisis, we are living through a status that will not only have great economic and vital transcendence, but will also be studied in the future as a milestone, perhaps, of a new historical era. In fact, there has been no shortage of media outlets that have made historical comparisons between the lethality of other pandemics and the one we are now suffering (as was done by ABC 21 March) or those who have turned to the past to see what lessons these pandemics can teach us for today's status (as did the BBC on 7 March).

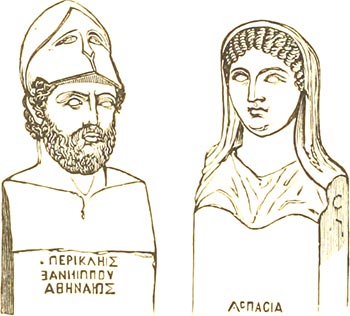

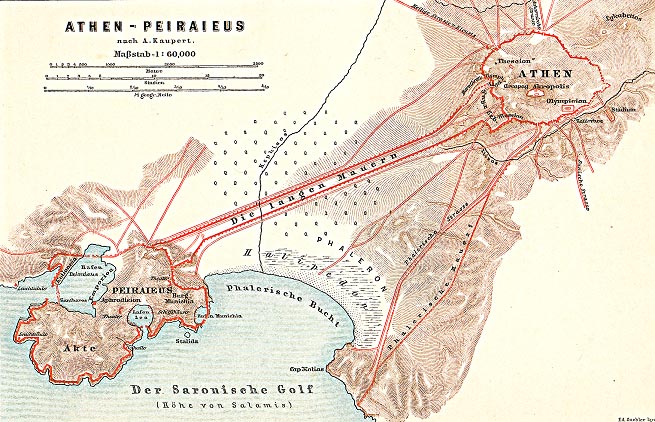

In these comparisons, looking to the classical world can, once again, come in handy, given the enduring importance of the Greco-Roman past as a true school of civilisation (1). Let us go back to classical Athens, to the admired Athens of Pericles, specifically to the period between 431 and 404 BC, the Peloponnesian Wars, one of the most exciting periods, especially in its preparations, in the history of antiquity. In 431 BC, the Greek strategist Pericles had articulated the resistance against the Lacedemonians - against the Spartans - by avoiding combat in the open field, forcing them into a siege war in a city that considered itself autonomous and self-sufficient thanks to the defensive system of the Long Walls, which, established a few years earlier, connected the port with the city centre. Athens - by then a city with a large and heterogeneous population which, decades earlier, had had to be divided into different regions - was thus witnessing the outbreak of war. Pericles exhorted his population to abandon their occupations and homes, to leave their lives in the countryside and to take refuge, all together and for an unknown length of time, in the astý, in the central part of the city, in its historic centre, so to speak. entrance This is Pericles' initial strategy, which will later be altered by the plague (2).

The Long Walls on the map.

It seemed to us that the account Thucydides, in the History of the Peloponnesian WarsWe thought that Thucydides' account of this passage in Book II of the aforementioned work could be relevant to today's status in which - perhapsdue to the irresponsibility of many- we are asked to make the simple gesture of staying at home. The classical world is thus once again present in today's world as a school from which we can learn, especially now that our politicians, probably without being aware of it, use the best of the procedures designed by classical rhetoric. The viewing of this speech, to give an example, of the President of the Government, or this one, of the leader of the civil service examination, can be inspiring in this sense, especially if we have in front of us the comparative graph that ABC has recently published in relation to the first and a historical one of G. Bush before the sad events of 11-S. All this in order to appeal to our sacrifice in the face of the sad events of 9/11 . All this to appeal to our sacrifice staff in favour of victory against this pandemic. Compare, if not, the reader, some of the clichés of these speeches with probably the best political speech of all time, the funeral oration of Pericles, dictated shortly after the events described here.

We leave below only the text of Thucydides, without further commentary, aware that its validity will make it unnecessary for any good reader to comment on it. The comparative and pedagogical nature of the mini-anthology offered here will come to the mind of any critical reader (on this occasion, we follow the translation of the Crítica edition -Barcelona, 2003-, at position of the incombustible and renowned Hellenist Francisco Rodríguez Adrados, almost the last living witness of a generation of scholars of Antiquity that seems unrepeatable).

[I]. A small sacrifice to contribute to a great cause: stay at home.

[13, 2] And, on the present status he gave them the same exhortations as usual; that they should prepare for war and bring into (the city) the things they had in the field; but that they should not go out to fight a battle, but should guard the city, taking refuge in it (...) and that most victories were won by clever planning and plenty of money.

[II]. The rhetoric of empowerment, at status de emergencia.

[13, 3-6 and 9] He exhorted them to be of good cheer, since every year there came into the city, without counting the other revenues, about six hundred talents of the tribute of the allies, and that in the Acropolis there were still then kept six thousand talents in coined silver (....); and, besides or less than five hundred talents in gold and uncoined silver in private and public offerings, in the sacred utensils used in processions and games, in spoils of the Persians, and the like (...) Thus he encouraged them on the financial side (...) Pericles also added other things which he used to say to convince the people that they would win the war.

[III]. The need to obey the authorities, and the discipline.

[14, 1 and 2] The Athenians on hearing him obeyed him and brought in from the camp their children and women and the household goods in general which they used in the camp, and even the timber of their own houses, took with them and transported to Euboea and the nearby islands their sheep and draught animals. They carried the evacuation with pain because most Athenians had generally always lived in the countryside.

[IV]. Change of habits and quarantine requirements.

[16] (... the Athenians) carried out the evacuation with their whole family with difficulty, especially since they had only recently recovered their possessions after the medical wars, and they were saddened and could not bear to leave their homes and their temples (...) and were about to change their way of life.

[V]. The opportunities of an unprecedented, almost unreal status .

[17, 3 and 4] (...) Many also settled in the towers of the walls and wherever each one could, for they were not together in the city, but later they lived in the space between the Long Walls, dividing it up, and in the greater part of Piraeus.

It is clear that, with or without difficulties, but always with resources, resorting to individual sacrifice with the general good in mind and, above all, with great faith in our abilities, we will manage to get out of this test which is beginning to be too long.

(1) Javier talks about it in another post of his.

(2) Which was the focus of a much-visited previous post on this blog at purpose of the coronavirus crisis.

Professor Javier Andreu's blog. READ.