Drawing: creativity and the foundation of the arts

PhotoM. Olmedo/Tiralíneas, 18th and 19th centuries. University of Navarra.

Basis of all arts in the creative process

The internship of drawing has accompanied human beings since the dawn of history, even before writing. It has been a fundamental means for learning and for the expression of ideas and thoughts. Albert Einstein expressed this idea with this phrase: "If I can't draw it, I don't understand it".

Drawing has been the basis and instrument of the creative process in all the arts, from architecture and figurative art to the so-called sumptuary arts. It has formed a major part in the genesis of the work of art and has been the foundation of the Fine Arts up to our times and fundamental in the training of artists, having had, in some countries, academies for their apprenticeship. In the average Age, many artisans obtained their promotion to mastery when they stopped staining their hands with lime and started using ink instead, due to their mastery of drawing.

Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), famous for his biographies of Italian artists, considered drawing to be "the father of the three arts: architecture, sculpture and painting", giving it an intellectual connotation as the plastic projection of the idea. The viceroy Palafox argued, in the following century, that the artist "first makes the idea in the imagination, then the drawing and finally the image".

The drawings can have a sense of a work final or they can be preparatory works for works made in other techniques and media. In this second option, he served for centuries as presentation for the client, as model to work on a larger scale with different supports and techniques.

When a commission was placed with agreement between the commissioner and the artist, the latter immediately proceeded to capture his invention in a drawing, sketch or model . Among the means that artists used to motivate their creativity and to draw, we should note everything they had within sight, written sources and engraved prints. Velázquez's master and father-in-law, Francisco Pacheco, in his Art of Painting (1649), put it this way: "Invention comes from good wit, and from having seen much, and from the imitation, copying and variety of many things, and from the news of history, and through the figure and movement of the significance of the passions, accidents and affections of the mind". The importance of apprenticeship, relationships with artists and patrons and travel were important aspects of the teachers' professional development in order to store visual and cultural sources in their minds. Those who possessed intellectual training were better prepared to include symbolic and allegorical elements in their works, which enriched paintings, building façades, altarpieces and book covers. Alberti, in the 15th century, proposed as model the pictor doctus versed in studia humanitatis and familiar with poets, orators and men of letters, "for from these erudite wits he will obtain not only excellent ornaments, but will also profit from his inventions".

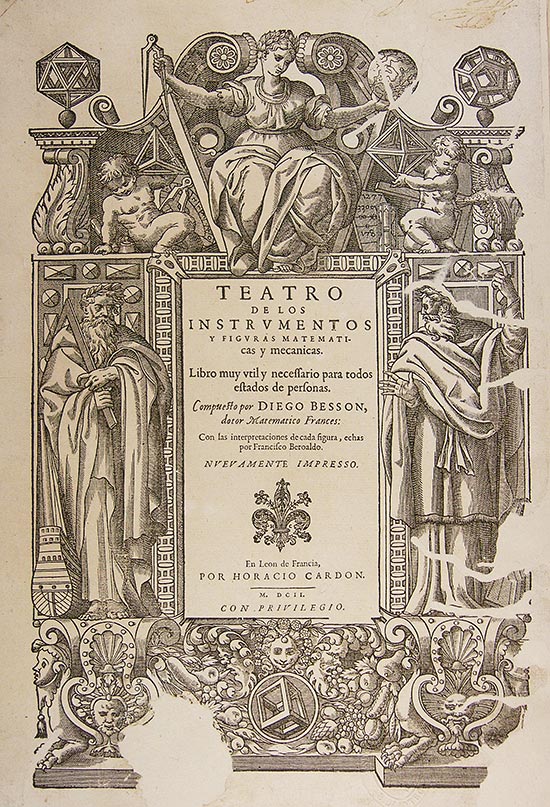

Cover of the 1602 edition of the Teatro de los instrumentos y figuras matematicas y mecanicas ... by Diego Besson. Library Services University of Navarra. Photo M. Calonge

The aim of the creative process traditionally consisted of obtaining beautiful works that would capture the attention, dialogue and empathy of those who approached them, always insisting on constancy, study and work, since, as Picasso pointed out: "Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working".

The testimony of a great creator: Bernini

The brilliant and multifaceted Gian Lorenzo Bernini, during his stay in Paris in June 1665, left his testimony about invention - today we would say creativity - and drawing, recounted by Paul Fréart de Chantelou in his Diary of the Gentleman Bernini's Journey to France. In his text we can read these paragraphs which speak for themselves about the characteristics of the artist's studio and the relationship between creation and drawing. Thus, we read: "Having gone afterwards from his room, where we were then, to his gallery, he told me that in Rome he had one in his house, completely similar, that it is there that he does most of his compositions while walking around; that he marks on the wall, with charcoal, the ideas of things as they come to his mind, which is what lively spirits with great imagination usually do: they pile up on the same topic ideas and ideas. When one comes to them, they draw it, when a second one comes to them, they write it down too, then a third and a fourth, without purging or perfecting any of them, always sticking to the last production for a particular love of novelty. That the thing to do on such an occasion to remedy this defect, is to let these different ideas rest there, without looking at them for a month or two. After that time, one is in a position to choose the one that is best; that if one happens to be in a hurry and the one for whom one is working does not give so much time, one must have recourse to those glasses that change the colour of objects, or those others that make them look bigger or smaller, or look at them upside down. In short, to seek by means of these changes of colour, size and status, to remedy the deception of the love of novelty, which almost always prevents us from choosing the best idea".

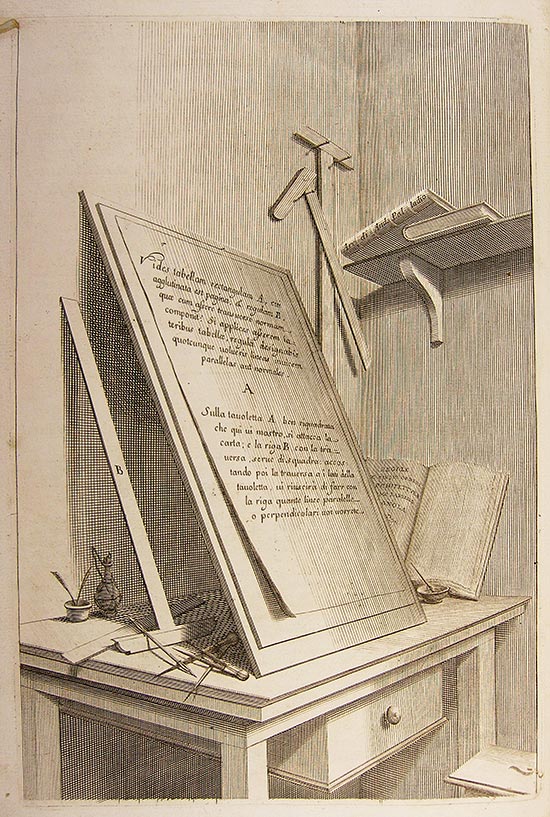

Plate from the book by Andrea Pozzo, Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum published in Rome, 1693-1700. Library Services University of Navarra Photo M. Calonge

To find out more

CHANTELOU, P. F., Diario del viaje del caballero Bernini a Francia, Madrid, high school de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales, 1986.

Instruments for Creativity. Drawing and construction tools from the 17th to the 20th centuries. Collection atelier Joaquín Lorda. exhibition virtual de la Biblitoteca de la Universidad de Navarra, May 2019.

The artist's training from Leonardo to Picasso. Aproximación de la teaching y el aprendizaje de las Bellas Artes. Madrid, Royal Academy of San Fernando. Calcografía Nacional, 1989