The image of loneliness in the arts and some examples in Navarre

PhotoJ. L. Larrión/Nonovo-Hispanic painting by Blas Enríquez, c. 1780, on framework of silver punched in Mexico. Private collection.

Devotion to the Virgin's sorrows was promoted in the 13th century by the Servite Order. Its feast dates back to 1413 in Cologne, when it replaced the celebration of Our Lady of the Passion - whose iconography aroused controversy as theologians saw her syncope or fainting as not in keeping with Mary - and thus counteracted the iconoclastic movement of the followers of John Huss.

The cult and the feast spread throughout Europe and Latin America during the Ancien Régime. Until a few decades ago there were two festivals in the liturgical calendar dedicated to the Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin: the first on Passion Friday, also called Friday of Sorrows, and the second on 15 September, the day on which the Glorious Sorrows of Our Lady are commemorated. Both spread widely, although the first was already very popular in plenary session of the Executive Council 16th century. The second was extended to the universal Church by Pope Pius VII in 1815, to commemorate its liberation from Napoleonic captivity. The duplication of the same invocation has recently led to the suppression of that of Friday of Sorrows, although it is maintained wherever there is a deep-rooted devotion.

Image of the Soledad by Gaspar Becerra, 1565, made with the sponsorship of Queen Isabella of Valois and dressed as a Spanish widow at the request of the Queen's hostess, the Countess of Ureña.

Until the 16th century, figurative artists used three main types to express the Virgin's sorrows. The first corresponds to the last scene of Christ's Passion, at the moment of leaving his dead body in the tomb. Mary appears accompanied by St John, the Marys, Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, contemplating the corpse of her Son. Another way of depicting the topic of Sorrows is the Virgin with her son in her lap after, according to pious tradition, he was placed there by the holy men after being taken down from the cross. It is a medieval topic with strength in the Renaissance and known as the Pietà or the Virgin of Sorrows. Finally, the third consists of presenting Mary at the foot of the cross, with seven daggers alluding to her seven sorrows, or a single sword as a recapitulation of all of them. Numerous engravings and paintings, especially from the Counter-Reformation period, adopted this subject.

The topic de la Soledad de la Virgen is very Hispanic and a new way of representing the Virgin's sorrows. Outside Spain, the version of the Virgin alone, unaccompanied, self-absorbed, after the burial of Christ, dressed in widow's robes and not with a sword stuck in her chest, but at most contemplating or holding some of the instruments of the Passion, was hardly ever depicted.

development With precedents in some Flemish prints and specific French sculptures by Germain Pilon, the topic would become very popular in Spain with the sculpture made by Gaspar Becerra in 1565, with the sponsorship of Queen Isabella of Valois and her chambermaid the Countess of Ureña, to whom we owe the dress of the image, in the style of Spanish widows, with monk's robes and a large black cloak. Throughout the following centuries, the model spread throughout the peninsular territories, always obeying the Madrid reference. Paintings, candlestick and round images, engravings, medals and scapulars bear witness to this.

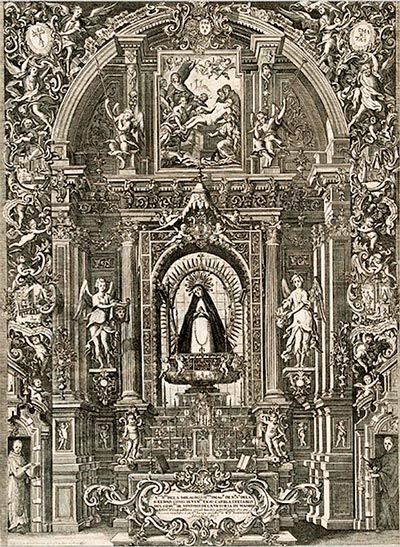

Engraving of the altarpiece Soledad de la Victoria de Madrid, by Fray Matías de Irala, 1726. Private collection

Artists such as Alonso Cano, José de Mora, La Roldana and Carmona left exquisite examples of this iconography, despite the civil service examination of some theologians who criticised their tears and other extremes. Juan Interián de Ayala, in his work El pintor cristiano y erudito... ( Latin edition in 1730 and Spanish edition in 1782), in which he states: "The Blessed Virgin Mary, deprived of her Son after He had been buried, is too often painted in the manner in which noble widows dressed in the time of our ancestors. You will see there the whole body of the Virgin clothed in black garments covering other thinner ones made of white linen; so that she is seen not only clothed from neck to toe, but also with her arms girded together before her breast, showing the fingers of her hands in a complicated manner; and even a veil of transparent silk is placed before her face, covering them, which leave reaches down to her feet. And finally, a rosary is foolishly placed around her neck. These are not such holy things to be joked about, but to be treated with due reverence; for at least the most learned consider them to be not only far removed from historical truth and faith, but also from solid piety and proper dignity. Nor can it be objected that in this way the sadness and grief of the Virgin is better represented than in any other, for she is compared to a widow in anguish and weeping at the death of her husband or her son. I am not of this opinion...".

In Navarre

Numerous examples of this iconography of the Solitude are preserved in Navarre, mostly from the 17th and 18th centuries, almost always in churches. Its images took on special prominence during Holy Week on the occasion of the Procession of the Holy Burial, where it was paraded at the end, after the ecclesiastical and civil presidency and in the functions of the Descent from the Cross or the Desenclavo (Desenclavo).

The dress image of Corella is the work of Pedro Sanz de Ribaflecha (1655), while that of the parish church of San Nicolás in Pamplona is one of the few that we have preserved, with a round figure, but following in all its characteristics Becerra's model . The one in the monastery of Fitero had a confraternity documented in 1627, was donated to the Vera Cruz confraternity in 1659 and in 1679 was transferred to the church by order of the Saint official document.

Round figure of La Soledad in the parish church of San Nicolás in Pamplona, late 17th century.

The candlestick image of the Carmelites of Araceli de Corella was a great devotion of the Goyeneche family of Pamplona, specifically Pedro Fermín Goyeneche and his father made several foundations under their board of trustees in 1734, 1735 and other dates. The 1735 foundation stipulated a perpetual report of a sung mass with incense and a solemn Salve on the day of the Virgen de los Dolores, entrusting it to Doña María Josefa Mendinueta, his wife. On the other hand, the image was to have a lamp lit for three hours every Friday of the year, with candles in the morning and afternoon, and four candles on Fridays during Lent. It is possible that both the image and its decoration, as well as the silver diadem it wears, may have been paid for by them.

Very interesting is the contract signed for that of the parish church of Cintruénigo, which was made by the sculptor Marcos de Angós, position , in 1728. The contract signed for its execution reads as follows: "another effigy of Our Lady of Solitude with the movements of genuflection and others that are customary, denoting the tears that the passage requires, with the liberal movements of head and hands, running the stage design with the greatest dissimulation so that she can raise and lower her head and hands, as well as the necessary action to embrace her son, opening and closing her hands". The one in the parish church of Lesaca, the work of Tomás de Jáuregui, 1751-1754, presides over its altarpiece. Other altarpieces dedicated to him are preserved in Viana, Aguilar de Codés, Miranda de Arga, Olite (Franciscans), Azpilcueta, Labayen, Sumbilla and Cintruénigo. Very interesting is the panel with its depiction of the stalls of the sanctuary of Ujué, the work of Manuel Martín de Ontañón (1774).

Dress image of the Soledad de Corella, the work of Pedro Sanz de Ribaflecha (1655).

The abundance of these images was due to the worship they received throughout the year, but above all to the prominence they took on during Lent and Holy Week, both in the Good Friday processions and in the Descent from the Cross.

Of the bust version of the Soledad, the magnificent sculpture by Pedro de Mena of Recoletas de Pamplona, a work datable to around 1670-1680, stands out. This piece, A in its execution, was attributed by Professor García Gainza. It corresponds to the type of image of Solitude that the famous sculptor from Granada disseminated in different examples located in Alba de Tormes, Malaga Cathedral and the Descalzas Reales.

Among the paintings, mention should be made of the 17th-century paintings of the old main altarpiece of the Barbazana in Pamplona cathedral and the painting of the Rosary in Corella. The Lecároz painting, paid for by the Jáuregui family between 1762 and 1767, also stands out. Of New Spanish origin is an interesting copper painting framed in silver, dated around 1780 and signed by Blas Enríquez. The female cloisters of the different religious orders also conserve numerous canvases from topic, with those of the Recollects of Pamplona, the Poor Clares of Estella and the Capuchin and Dominican nuns of Tudela standing out.

Altar of La Soledad in the parish church of Lecároz, paid for by the Jáuregui brothers, 1762-1767.

The last great icon of this subject of the Soledad was undoubtedly the one carved by the Catalan sculptor Rosendo Nobas for Pamplona City Council in 1884, which is worshipped in the parish church of San Lorenzo in Pamplona. In the capital of Navarre itself, a curious publication of 1888 on the order of the Procession of the Holy Burial states that the Soledad was the eighth and last step of the procession with this paragraph: "Once the official document of the burial of Jesus had finished, his Most Holy Mother, filled with a new sorrow at being alone and deprived not only of her living Son, but also of his dead body, decided to return to Jerusalem, and she did so accompanied in this sorrowful procession by the knights Joseph and Nicodemus. It is not much, then, that twelve knights from Pamplona, invited by the Town Council, precede the procession of the Soledad, illuminating it. This paso has also been enriched with a new platform at the expense of the Corporation".

Her return to the parish of San Lorenzo on Good Friday also has the sense of solitude of the Mother of God.

Photograph of the paso de la Soledad de Pamplona, after the Sermón de las Siete Palabras, in 1954. Photo Julio Cía. file Municipal of Pamplona

To find out more

RODRÍGUEZ G. de CEBALLOS, A., "La literatura ascética y la retórica cristiana reflejados en el arte de la Edad Moderna", Lecturas de Historia del Arte. Ephialte (1990), pp. 80-90.