Don Juan de Palafox y Mendoza. A surname in core topic of acrostics

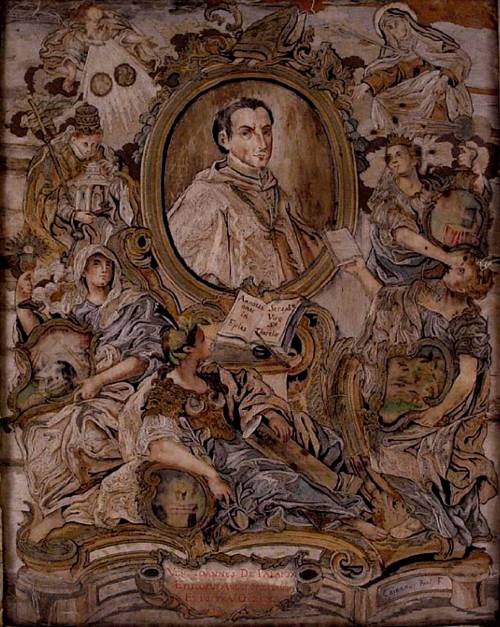

Photo / Portrait of Palafox in the Carmelitas de Ayacucho with symbolic elements copied from the engraving of the character made by Pedro Villafranca in 1665.

Some years ago, in the context of a congress on La Emblemática en el Siglo de Oro, we presented a hypothesis about the use and meaning that Palafox makes of surname Mendoza. In later publications we explained and justified it. Since the death of his father on February 25, 1625, he used it regularly.

Don Juan de Palafox, as an illegitimate son -a very serious disadvantage in that 17th century- translated, as in other similar cases, into an obsession for loyalty to his family and his father in particular. Also, from the point of view of the Count-Duke, who captured him and promoted him to the tasks of government, the subject of subordinates, lacking a secure place in society and affected by the circumstances of their birth and, therefore, dependent on the royal favor for the promotion of their careers, were suitable.

Until the mid-twenties, she had signed her documents as Juan de Palafox or Juan de Palafox y Rebolledo, since the latter surname was inseparable from the Palafox lineage. For Cristina de Arteaga, the surname Mendoza, of solid nobiliary resonances, constituted a cover letter for her relations in Castilian lands and was carried by her great-great-grandmother, being these two reasons what would have led her to introduce such a novelty. To this we must add the wishes of the monarch himself and of Olivares, expressed on numerous occasions, in the sense that the Palafox family should be Castilianized, for which his younger brothers Francisco and Lucrecia arrived at the royal palace itself.

Juan de Palafox in an embroidery signed by Cayetanus Pasi, following the composition of the engraving by Franz Regis Goetz, c. 1770. Private collection

Trying to find out more about the spatio-temporal circumstances in which Don Juan de Palafox adds the Mendoza to his name, we observe that it coincides with the beginning of his public life (Cortes de Monzón-Calatayud, 1625), with the death of his father (February 27, 1625), with his visits to Zaragoza and the arrival of his natural mother Ana de Casanate (then Ana de la Madre de Dios) to the Aragonese capital to found the convent of Santa Teresa (1624). In final, when he appeared before the society and needed a second surname with which to give an answer to so many and so many questions and interrogations about his mother, since it was of public domain that he was the natural son of the Marquis of Ariza, he decided for the surname Mendoza.

She concealed her mother's name in public and private documents. Among the former, let us cite her Interior Life or autobiography, where she states that "shebecame a nun and was prelate several times and foundress in that holy and harsh recollection and lived and died with singular example, spirit and penitence". Among those of a private nature, let us remember the plea to the pope in 1635 not to declare the name of her mother if it was necessary to make any transcript, preserved in the Vatican file . From its contents, we extract these sentences, where she affirms that she lived and was "prelate in a certain monastery of nuns, which universally enjoys excellent fame and authority.... and if the name of the aforementioned was declared, she would be in danger of her life and notorious infamy, as well as her most noble house and also the convent, and probably capital enmities and rivalries would arise between the two houses of father and mother in the kingdom of Aragon, from where they originate".

His justification in an acrostic is perfectly in tune with the symbolic culture of the Baroque and with the refinement and refined Education he had received in Alcalá and Salamanca. For the rest, many of his behaviors in society are typical of the baroque man: he takes off his episcopal cassock and moults it and replaces it with another black one when he leaves the territory of his diocese; he takes the skull in the pulpit, arranges the opening of his heart to introduce in it a pious plate, advises his family to acquire the board of trustees of the parish of Ariza, cries and makes the auditorium cry .... etc.). We also know that he liked very much the employment of metaphors and other literary figures and that the books of his particular Library Services were deeply underlined and annotated in his own handwriting. Let us add that, of agreement with the tastes of the time, he cultivated a fondness for jousting, tournaments and poetic academies, at the same time that he made puns, such as the one referred to by his biographer, when dealing with his humility: "To this purpose he used to say that he could not find such a complete and fitting anagram in both languages, Latin and Castilian, as were these corpus, porcus, body and swine, and that in the human body where the rational soul was imprisoned and captive, were enclosed as many disgusting and filthy things as could be signified.......".

For the onomastic of Mendoça we proposed a reading in the form of an acrostic that is legible both from the beginning of the word and from the end to the beginning, and that developed would read: Ana Cesaraugustae Ordinis Discalceatorum Nomen Est Matris; or, Matris Est Nomen Discalceatorum OrdinisÇesaraugustae Ana; which translated says "The name of our mother is Ana of the Order of the Discalced, of Zaragoza". In this regard, we must remember how acrostics were used for various purposes in all times, being one of the most important resources to sharpen the imagination and ingenuity. Sometimes the complexity surrounding these compositions is great, especially when mixed with other ingenious procedures.

With the aforementioned resource, Juan de Palafox, recognized his mother, Ana de la Madre de Dios (Casanate y Espés, Tarazona, 1570 - Zaragoza, 1638)), a discalced Carmelite nun. The hypothetical Lucrecia de Mendoza, whom the legend even made Marquesa de Mendoza, never existed.

We can still go further in the contents of authentic hieroglyphic of the hypothetical Lucrecia de Mendoza, in this case in the name of her mother, also placed in core topic. We know that, in the Summary of the transcript of Beatification, there is the news that, on a certain occasion, having been asked by a confidant of the bishop what was the name of his mother, the prelate answered that Doña Lucrecia de Mendoza. And again we wonder why the name of Lucrecia, when we know that there was no lady who responded to the real name of Lucrecia de Mendoza? The answer must be sought, once again, in readings that go beyond a name, in this case the myth of Lucrecia itself. Palafox used, when questioned, perhaps inopportunely or insistently, with an assumed name and double reading, in final, with an answer in core topic. If Lucretia in antiquity had put an end to her days after the attack against her chastity made by King Tarquinio, her mother -Ana de Casanate-, as a Catholic of the Counter-Reformation period who believed in the value of penance and forgiveness of sins, was going to purge and do penance, she was going to purge and to make the penance continued in one of the most austere branches of the reformed orders, exchanging this world for another one inside the cloister and enclosure of the Carmelite descalcez, as Palafox affirms in the text before mentioned, extracted of her Confessions or Interior Life.

To find out more

ARTEAGA Y FALGUERA, C., Una mitra sobre dos mundos. La del Venerable Don Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, Seville, Gráficas Salesianas, 1985.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "Alegoría y Emblemática en torno al retrato de don Juan de Palafox", La Emblemática en el Siglo de Oro, Madrid, Akal, 2000, pp. 163-187.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., Birth and Infancy of the Venerable Palafox2nd corrected and enlarged edition, Pamplona, association de Amigos del Monasterio de Fitero, 2000.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "Desde las celosías del Carmelo: la madre de Palafox", En sintonía con Santa Teresa. Juan de Palafox and the Discalced Carmelites in 12 programs of study, Pamplona, Government of Navarra-committee Nacional del V Centenario del V Centenario del Nacimiento de Santa Teresa-Ayuntamiento de Fitero, 2014, pp. 45-79.

ISRAEL, J. I., Razas, clases sociales y vida política en el México colonial 1610-1670, Mexico, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1996.

PALAFOX Y MENDOZA, J., Vida Interior, In Obras Completas, Vol. I, Madrid, Gabriel Ramírez, 1762.