Festivities and art around the Immaculate Conception in Navarre (I)

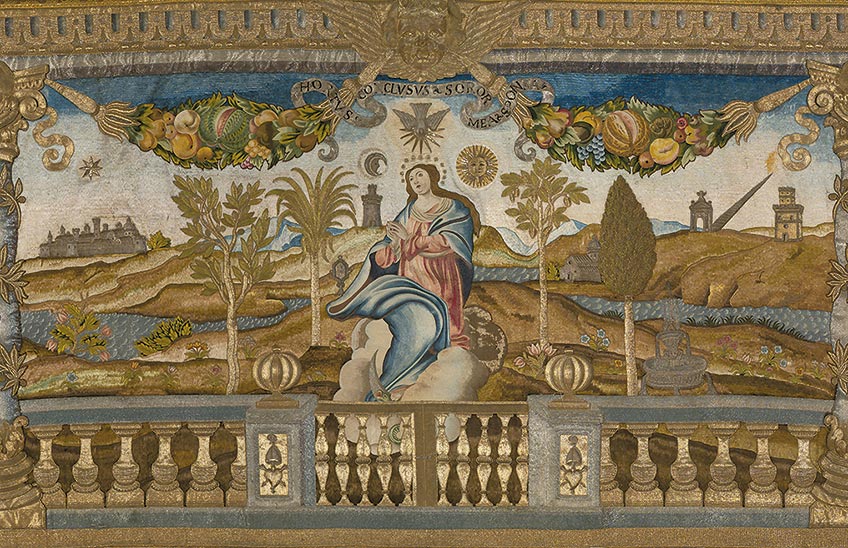

PhotoJ. L. Larrión/Neapolitan front of the Augustinian Recollect Nuns of Pamplona. 1665

A social and cultural phenomenon that surpassed the religious fact.

Some religious events of subject , with enormous cultural content, became sociological. Among them, we can cite that of the Immaculate Conception. Its entrance in art, literature and popular piety in the Hispanic world during the 17th century was a phenomenon that involved the entire social fabric. Its images, in different spheres and with different techniques, transcended the strictly religious to become part of a broader dimension: the cultural. The topic gave rise to unique experiences on the part of the people, as well as a veritable hotbed of ideas, images and writings by theologians, artists and members of other social elites.

Navarrese society also lived that mystery and pious belief with intensity, as it was not dogma until 1854. Some towns proclaimed her patron saint, others denounced the Dominicans who preached against popular sentiment and others took their own particular conceptionist vows. Countless vows, brotherhoods, congregations, greetings, festivals and tournaments bear witness to how the mere religious fact became sociological and cultural.

Canvas of the Benedictine Sisters of Lumbier, today in Alzuza, by Diego González de la Vega, 1677. Photo J. L. Larrión

Vows of the institutions and co-patronage of the kingdom

The immaculist movement was present early on in Navarre's institutions, both in those of the Kingdom and in local and diocesan institutions, as well as in those of the religious orders - especially the Jesuits and Franciscans - and of many confraternities. The Conceptionist oath of the Cortes of Navarre in 1621 and the vows of the main town councils (Pamplona in 1618, Tudela in 1619, Estella in 1622, Olite in 1624 and Sangüesa in 1625) are a good example of this sample . The same sentiment led to the obligation to swear an oath to defend the mystery for all those who settled or became naturalised in these lands, or who became part of a strictly civil or religious institution, either the Cortes of Navarre or the cathedral chapter. To all this must be added the festive celebrations, processions, music, tournaments and amusements with which the people celebrated the fiesta in an extrovert manner. The pleasure of feeling and the joy of celebrating were very much in tune with the art and culture of the Baroque, which always tended to captivate people through the senses, which were more fragile than the intellect.

In 1760 the Pope, at the request of Charles III, declared the Immaculate Conception to be the patron saint of Spain. The Diputación de Navarra received the royal missive in 1761 and left the decision on how to celebrate the feast to be determined by the Kingdom gathered in Cortes. In 1765, the latter institution decided to commemorate the feast as was done with the patron saints, with the Immaculate Conception appearing, in successive years, as co-patron saint of the Kingdom in its official acts.

Some Navarrese towns such as Fitero, Cintruénigo, Corella, Olite and Arróniz proclaimed her patron saint or co-patron saint around 1643, with the corresponding vote if they had not done so previously, while others denounced the Dominican friars who preached against popular belief.

Sculpture from Valladolid from 1681 from the seminar Conciliar de Pamplona, from the high school of the Jesuits.

The fiesta multiplied in Pamplona and a great tournament in Tudela

In the capital of Navarre, the cathedral, the Franciscans, the Augustinian Recollect nuns in a very special way, and the Capuchins competed with services and celebrations around the 8th of December, in some cases with a novena and, in general, with a very solemn octave. The kingdom and the Pamplona regiment did the same. issue The cathedral's chapel of music had to attend to perform such a large number of functions that the timetables of the different services had to be rationalised. Even the congregation of the Immaculate Conception of the Jesuits, established in 1613, was obliged to celebrate its main feast day on 21 December, as the 8th and its octave were full of services in other churches in the city. Its congregants organised a peal of bells on the eve, accompanied by shawms, a large bonfire in front of the prefect's house and the placing of an image of the Immaculate Conception between two luminaries in the windows of all their houses.

In the capital of La Ribera and in honour of the Immaculate Conception, a A tournament was organised in 1620, perhaps the most important of those held in the city in the centuries of the Modern Age. As is well known, a tournament was reminiscent of medieval chivalric exercises with mock battles. It was considered the noblest exercise for knights, although it declined in Castile and was maintained with some strength in the territories of the Crown of Aragon. Its protagonists were the nobles, from whose ranks the actors and even the spectators were recruited, in many cases.

As in festivals of this kind, the poster announcing the event listed the gentlemen taking part, and their relationship explains everything related to the stage, the pomp, the luxury and the ostentation of the event, all of them with one purpose: to captivate the spectators through the power of the senses, by means of oral and plastic means. The spaces of the festival, as expected, were transformed for the event with banners, pennants, and rich taffeta hangings and banners.

There was no shortage of music on his development , both of purely civil and military content. In this respect, it should be remembered that music was in this, as in other religious and recreational festivities, a real soundtrack, which underlined moments charged with symbols, ceremonies that spoke with their gestures, as well as the wordless actions of those who acted. Gunpowder, drums, fifes and snares cooperated in that world of sounds to underline some moments with sublime effectiveness, such as the arrival of the infernal monster, a kind of machine with fires and rockets of all kinds subject.

A sanctuary of special significance in Cintruénigo

For a long time the primacy of this sanctuary in Navarre and even in Spain in its dedication to the Immaculate Conception has been defended. Today it cannot be maintained, not even in Navarre, where it is half a century ahead of the Shrine of Our Lady of Fair Love de la Concepción del Monte de Torralba del Río. Nevertheless, the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception has been one of the most important places of devotion to the Immaculate Conception in the whole of Navarre.

Its confraternity dates back to 1580. Coinciding with this date, the primitive sanctuary was built and the image was commissioned, a work that fits perfectly with the style of a Romanist master resident in Tudela, Bernal de Gabadi, who had trained with Gaspar Becerra in one of the masterpieces of the Hispanic Renaissance: the altarpiece of Astorga. The sanctuary was enlarged between 1654 and 1662. The current altarpiece is the work of Francisco San Juan (1674). plenary session of the Executive Council In the 18th century a sumptuous chapel was built and a new doorway was constructed.

The festivities of subject that the Cintrúenigo regiment prepared on several occasions were extremely important, especially in the 17th century. They included bullfights, bonfires, music, comedies, religious functions, processions and transfers of the image, carried by the brotherhood of the crossbowmen of the Holy Cross.

Image of the Immaculate Conception of Cintruénigo, by Bernal de Gabadi, c. 1580

To find out more

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., The Immaculate Conception in Navarre. Art and devotion during the centuries of the Baroque. Mentors, artists and iconography, Pamplona, Eunsa, 2004.