Festivities and art around the Immaculate Conception in Navarre (II)

FotoCedida/Detailof the canvas of the Immaculate Conception by Diego González de la Vega (1677) of the Benedictine Sisters of Lumbier, today in Alzuza.

Brotherhoods and festivities all over Navarre: bonfires, music, gunpowder and bells

A total of seventeen parishes are or were under his patronage: Egulbati, Ezperun, Garrués, Naguiz, Ollacarizqueta, Anchóriz, Errea, Ilúrdoz, Arive, Ongoz, Arce, Artozqui, Gurpegui, Ayanz, Uli de Lónguida, Uroz and Tirapu. There were sixteen hermitages, the oldest being that of La Concepción del Monte de Torralba del Río, built by the hermit Juan de Codés in 1540, although the most famous was that of Cintruénigo, with the greatest social, devotional and artistic projection.

Among the confraternities we know of those of Ablitas (documented in 1562), Cintruénigo, Echarri-Aranaz, Lazagurría, Mendavia, Fitero, Corella, Artozqui, Lodosa, Legaria, Falces, Cárcar, Torralba del Río, Caparroso and Sangüesa. high school To these must be added some guilds such as the weavers' guild of Pamplona or the waxmakers' guild of Estella, the congregations of the Society of Jesus and the Lawyers' Guild of Pamplona, who venerated her as their patron saint.

In the different towns in Navarre where the day of the Conception was celebrated, with greater or lesser pomp, we find the typical elements of the traditional festivity: the sermon, the roar of gunpowder, the heat of the bonfires, the sound of the bells ringing in a special way, the chords of music and a rich ceremonial to accompany the authorities to the vespers, the mass and the procession of the day, where the sermon, commissioned specifically to someone with oratorical qualities in order to teach, delight and move people to behave, stood out. In some confraternities, such as that of Echarri-Aranaz, there was no shortage of warnings during pastoral visits about excessive eating and drinking on the pretext of the celebration. In Cintruénigo, there are even records of comedies being performed on the occasion of extraordinary celebrations.

Canvas by Juan Correa (1701) with the Immaculate Conception and Pedro Ramírez de Arellano

On the eve of the dogmatic declaration of 1854

Society lived this pious belief intensely, as it was not dogma until 1854. There were still places in the mid-19th century where neighbours exchanged the angelic greeting as a courtesy when they passed each other in the street. The parish priest of Lacunza, in 1849, reported that the inhabitants of that village used the Ave María Purísima, to greet each other, as "still, thank God, modern greetings have not yet been put in internship, in these people". In some towns where there was neither a confraternity nor a vote, some families defrayed the expenses of the fiesta, as was the case in Santacara, Aoiz and Aibar. Similarly, the custom was widespread on the same dates to begin sermons with the following salutation: "Blessed and praised be the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar and the Immaculate Conception of Mary our Lady conceived without stain of original sin in the first instant of her natural being. Amen". In Ochagavía, at the end of the rosary, the families prayed it like this: "May the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar and the pure and immaculate Conception of Mary Most Holy at the first moment of her natural being be forever blessed and praised. Amen.

These testimonies and many others reached the bishopric of Pamplona from the towns within its jurisdiction, in response to an edict and questionnaire on the topic of the Immaculate Conception in 1849, when the dogmatic declaration of Pius IX was making its way.

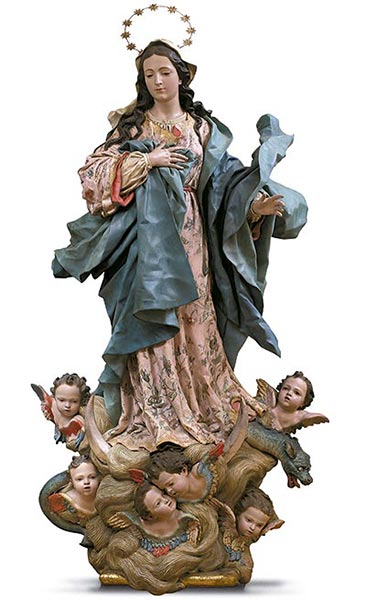

Sculpture by Luis Salvador Carmona de Lesaca c. 1753. Photo J. L. Larrión

Artistic expressions

Along with the festivities, music and public entertainment, the images of the Immaculate Conception, in their pictorial, plastic and engraved or embroidered versions, are the best testimony to the true dimension of this phenomenon. Prominent patrons, institutions, nobles, private individuals and confraternities commissioned sculptures, paintings, engravings, badges, medals and scapulars with the image of the Conception. Many of them have been preserved, constituting key pieces for analysing that reality from different points of view: historical, religious, traditional and artistic.

As for the sculptures, there is a marked difference between those of the 17th century and those of the following century. The former were of Castilian imprint, indebted to the models of the Valladolid sculptor Gregorio Fernández. Those of the main altarpieces of Arróniz and Arellano stand out, as well as that of Berriozar, paid for in 1632 by its abbot Don Nicolás Ezpeleta, from the house of the barons of his surname and viscounts of Val de Erro. From Valladolid came a singular carving, in 1681, destined for the high school of the Jesuits, where there was an important brotherhood of the Immaculate Conception, which today is preserved in the seminar of the capital of Navarre. The contributions of important schools are present in other localities. That of Ablitas suggests Andalusian models by Pablo de Rojas, those of Neapolitan origin are not lacking in some cloisters of nuns and it will not be rare to find some from workshops in La Rioja or Aragon in localities that once belonged to the bishoprics of Calahorra or Tarazona.

Confraternities of the Immaculate Conception and other devotions took vows of conception and commissioned paintings and sculptures. The Confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament of Tudela paid for a dress image in 1682, which is the one that is paraded in the procession on Easter morning in the famous Descent of the Angel.

Bernese delicacy and baroque style prevailed in the pieces imported in the 18th century from Aragon, Naples and the Spanish capital. Coinciding with the proclamation as patron saint of the Hispanic kingdoms in 1760, we find some unique pieces, some of which predate that event. Among those arriving from the Court in Madrid were the Lesaca, the work of Luis Salvador Carmona, those of Falces, Gaztelu by the same master and those of Arizcun and Bacaicoa. From Naples came the one that is venerated on the altarpiece of the Virgen del Camino in Pamplona, paid for by Agustín de Leiza y Eraso in 1772.

The chapter on painting is particularly rich, as Navarre has some unique works. Among those from the 16th century we should mention the panels from the church of Cerco de Artajona and the Renaissance paintings of Tudela and Olite. The works from the centuries of the Baroque period include works from the Madrid school, where the best art was consumed. Signatures by Marcos de Aguilera, González de la Vega, Ezquerra, Escalante, Miranda...etc., make up an outstanding list of canvases that were arriving at the places of reception of the artistic avant-garde which, at that time, were the convents and monasteries. To all these canvases must be added those produced by Vicente Berdusán, the best painter established in Navarre in the 17th century.

Neapolitan sculpture sent by Agustín de Leiza y Eraso for the altarpiece of the Virgen del Camino in Pamplona, in 1772. Photo J. L. Larrión

To find out more

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., The Immaculate Conception in Navarre. Art and devotion during the centuries of the Baroque. Mentors, artists and iconography, Pamplona, Eunsa, 2004.