A pair of copies in Navarra of the illustrated edition of the Life of St. Bernard of 1587.

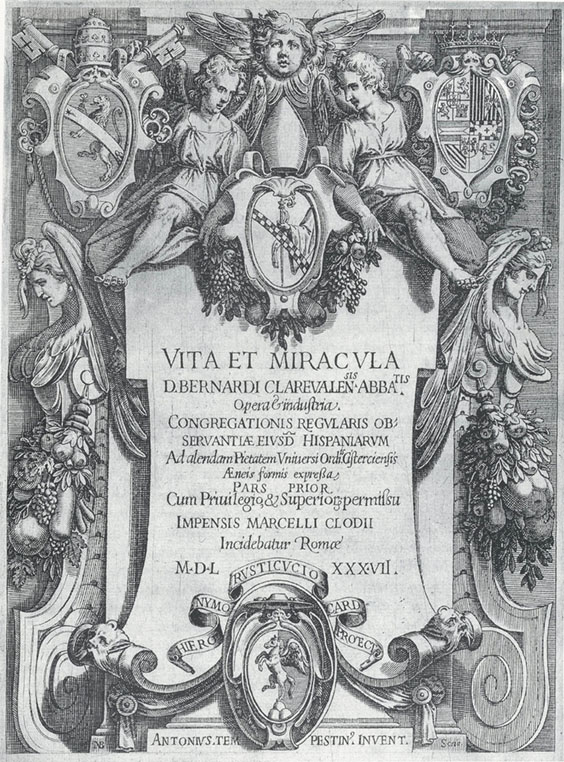

Photo /Detail of the engraving of St. Bernard with the arma Christi, from the illustrated life published in Rome in 1587.

At the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the following century, when the great European printers carried out publishing projects with excellent intaglio illustrations, their elegance dazzled individuals and institutions. That luxury would not reach the Spanish and Navarrese presses until the following century, in plenary session of the Executive Council reign of Charles III, so that illustrated copies were coveted throughout the sixteenth century from different spheres. Nobles and high ecclesiastics, with high purchasing power, were able to obtain those pieces with images, in a context in which time was abundant, and those who approached them "made of contemplation something useful, therapeutic, that elevated their spirit, brought them comfort and inspired fear" (D. Freedberg).

The religious orders, in Rome or Antwerp, commissioned illustrated lives of their founders that were circulated throughout Europe and America, and their compositions were copied in paintings and sculptural reliefs. The handwritten inscriptions of some books allow us to know the particular history of their acquisition and arrival at their destinations.

Cover of the Vita et miracula divi Bernardi Clarevalensis abbatis (Rome, 1587).

The one corresponding to St. Bernard, published in Rome in 1587, with the degree scroll de Vita et miracula divi Bernardi Clarevalensis abbatis, was made possible thanks to the Cistercian Congregation of the Crown of Castile and the sponsorship of Cardinal Jerónimo Rusticucio, protector of the Spanish Bernardines. It was conceived, to a large extent, as an illustration of the Vita Prima of St. Bernard, the most important hagiographic text referring to the saint, of which Fray Juan Álvaro Zapata, monk and future abbot of the monastery of Veruela, published a version at Spanish in 1597. The models of his prints are due to the invention of the famous Antonio Tempesta and their execution to Querubino Alberti, Filippo Galle and other outstanding engravers.

Currently, there are two copies of that edition in Navarre, one in Tulebras and the other in La Oliva, the latter with delicate calligraphic annotations on the backs of the stamps. In the case of the latter having belonged to the aforementioned monastery before the Disentailment, those texts must have been written by Father Compaño, a monk from Poblet, a book writer, who was sent by Abbot Esteban Guerra (1585-1588) to write some beautiful cantorales for the Divine official document .

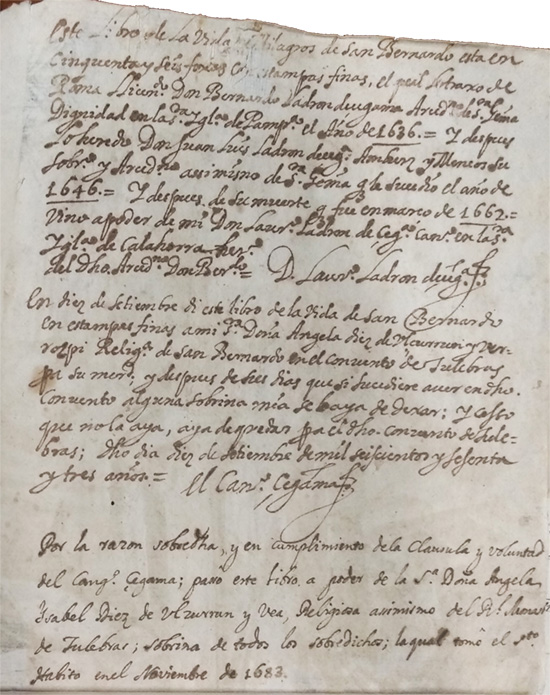

grade manuscript in the copy of Tulebras, which gives an account of its owners since it was acquired in Rome in 1636, until it reached the monastery of Navarre.

Of the copy of Tulebras, we know everything relative to its particular history, thanks to a long handwritten registration on the back of one of its stamps. It was acquired in Rome, in 1633, by the canon of the cathedral of Pamplona and archdeacon of Santa Gema, Bernardo Ladrón de Cegama, warning that it contained "cinquenta y seis foxas con estampas finas". Upon his death, it passed to his nephew Juan Luis Ladrón de Cegama, who occupied the same dignity from 1646. When the latter died, it went to the Calaguritan canon Laurencio Ladrón de Cegama, who gave it in 1663 to the nun of Tulebras, Ángela Díez de Ulzurrun y Berrozpe, "and after her days, if there should be a niece of mine in said convent, she should leave it and if there is none, it should be left for the said convent of Tulebras". A later annotation of 1683, picks up this apostille: "For the aforementioned reason, and in fulfillment of the clause and will of Canon Cegama, this book passed to the power of Mrs. Ángela Ysabel Díez de Ulzurrun y Vea, religious also of the Royal Monastery of Tulebras, niece of all the aforementioned, who took the holy habit in November of 1683" and was abbess, exceptionally, during four quadrenniums.

Another copy must also have arrived, with all certainty, at the Cistercian monastery of Fitero, as attested by paintings of different altarpieces of its abbey church, especially two panels of the main altarpiece, the work of Rolan Mois (1590), which copy the prints of the aforementioned book.