The compass and its meaning: some examples

A couple of examples from the 16th century

As is well known, art became more erudite during the Renaissance, combining with great force optics, geometry, Anatomy, physiognomy, expression of the passions, natural history, architecture, antiquarianism and mythology. The few depictions we have of 16th-century masters place special emphasis on the use of compasses and squares to distinguish them from journeymen, stonemasons and masons.

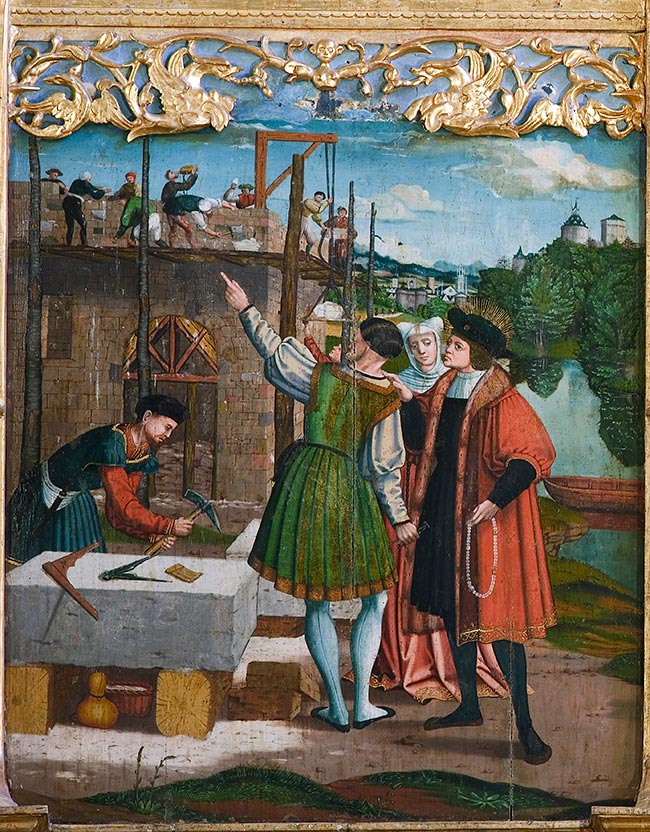

In the main altarpiece at Ororbia (c.1523-24) we find painted stories of Saint Julian the Hospitaller, whose textual sources refer to the Golden Legend. The panel provides a chronicle of how construction was carried out in those decades, with wood playing a major role in the use of falsework, scaffolding and elementary cranes. In the foreground, the patron, Saint Julian, converses with the master manager of the factory, who holds a small, delicate compass in his right hand, while an official cuts an ashlar with a square, compass and brush beside him.

In the sacristy of the chapel of the Holy Spirit in Tudela cathedral is an Early Renaissance panel of Aragonese origin that depicts Saint Joseph in one of the earliest examples in which the saint is depicted as a young man. It is accompanied by a pair of donors and must be dated to around 1540. A large square identifies the saint as a carpenter. However, it is the compass, strategically placed in the central part of the seat, next to the donors, an element that seems to go further than indicating the saint's official document . It is a panel that has its own little secrets to be solved and which requires a very thorough research .

|

Tablet of St Joseph with donors in Tudela Cathedral, c. 1540. Photo J. L. Larrión |

St. Joseph of Subiza with the compass as an attribute

The image of Saint Joseph on the main altarpiece in Subiza is the work of Domingo de Lusa. Instead of the saw, the saint exceptionally carries a compass. In the first decades of the 17th century, Father Jerónimo Gracián, in his work on the saint, states that Saint Joseph practised other mechanical arts, although he devoted himself to the arts of wood, having carried out different works in as many specialities, such as living works (waterwheels, ploughs and carts) and dead works (tables, benches... etc.), of raw work or carving, and even tracings or models, tasks typical of old carpenters.

In dealing with this last aspect, he draws a parallel with the work of the Redemption and the role of the Holy Patriarch in it, explaining the function of the outstanding carpenter and his intervention in the plans of the buildings, at a time when the word architect is used in Spain, at reference letter to the one who designs polychrome wooden altarpieces. This is what the aforementioned Father Jerónimo Gracián wrote about the official document of Saint Joseph: "A great master who wants to build a sumptuous palace usually chooses officers to help him, labourers to serve him, and looks for suitable materials for the building; but before he sets to work, neither orders nor commands the officers who are to work, he looks for an old and experienced carpenter and discusses with him the building he intends to build. And the two of them alone draw the plan, make the design, make the model and, after everything has been foreseen, pointed out and agreed, they set to work".

|

Image of St. Joseph with the child accompanied by the compass. Parish of Subiza, by Domingo de Lusa, beginning of the 17th century. Photo Catalog Monumental de Navarra |

Detail of the panel of the main altarpiece with Saint Julian visiting the hospital works, c. 1523-1524. Photo Historical Heritage Service. Government of Navarre |

Together with all the carpenter's tools in an altarpiece in Puente la Reina.

We finish with a visit to reference letter to the reliefs of the netos of the bench of the altarpiece of San José in the Comendadoras de Sancti Spiritus in Puente la Reina, which presents the most complete example of all the tools of a carpenter's workshop, with the finesse of a master who carved very well in the rococo period. The piece was commissioned along with three other altarpieces for the same church in 1768 by Nicolás Pejón "a sculptor, carver and architect by profession". The gilding of all of them was the work of Juan José del Rey. The following perfectly carved motifs can be seen on the bench of the altarpiece: files, axe, hammer, saw, chisel, gouge, compass, mallet, tongs, square, ruler, sergeant and bench of the official document. This is something exceptional in an altarpiece from Navarre.

|

Tools from the carpentry workshop on the bench of the altarpiece of San José de las Comendadoras de Puente la Reina, by Francisco Nicolás Pejón, 1768. Photo J. I. Riezu |

To find out more

CRIADO MAINAR, J., "Retablo de San José", Tudela el bequest de una catedral. Pamplona, Fundación para la Conservación del Patrimonio Histórico de Navarra, 2006, pp. 199-200.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., El retablo barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2003.

JERÓNIMO GRACIÁN DE LA MADRE DE DIOS, Sumario y excelencias del glorioso San José esposo de María (1597), introduction by J. A. CARRASCO, Valladolid, Centro Español de Investigaciones Josefinas, 1995.

MARTÍNEZ ÁLAVA, C., TARIFA CASTILLA, M. J. and LATORRE ZUBIRI, J., La iglesia de San Julián de Ororbia. Historia y restauración, Ororbia, Concejo de Ororbia, 2014.