Bells: tangible and intangible heritage. The largest in use in Spain, in Pamplona.

FotoMiguelBretos/Campaneros with the bell Maria in the cathedral on the day of Santiago de Compostela in 2021.

In addition to their material value as tangible cultural assets, bells also hold many of the secrets of intangible heritage, reminding us, with their different tolls, of the daily life of our ancestors, who lived attentive to their sounds, marking and organising their daily lives.

In the West they were adopted by the Church in the 5th century, although they had been known for centuries. The Romans called them tintinabula and the Christians signum, because they were used to announce their services. At least from the 7th century onwards, they were called bells. According to documentary references and testimonies that have survived to the present day, the early medieval models were small in size, although over time they successively increased in size until, in the 13th century, they became large, in a process that continued to grow thereafter. The most common shape of the bells is an inverted cup, rung by means of a rope attached to the clapper.

Traditionally they have been cast in bronze, although different alloys have been used depending on the period and territory, with iron, silver and even gold being used. Many of them bear inscriptions from psalms and liturgical hymns and, of course, usually have their name engraved on them. The ritual for their blessing, as well as being recorded in liturgical books, can be recreated visually in an engraving by B. Picart which illustrates the edition of the Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde ( 1723).

Blessing of the bell, according to an engraving by B. Picart in the work Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde ( 1723).

Blessing of the bell, according to an engraving by B. Picart in the work Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde ( 1723).

Bells are always housed in towers and belfries. The towers, which also housed the conjuratories, acquired a great development as the uses of the bells multiplied, not only to call the faithful and signal religious festivals, but also to govern civic life with the advertisement of the hours, warnings of fires, wars and other events of a civil nature.

Their sounds on all subject of parties and celebrations.

The functions of the bells have been secularly liturgical and horary, with some bells being used for liturgical purposes as well as for a tower clock. The ceremonial for the divine worship of cathedrals and temples had codified the different tolls as an external expression of festivities of a different character. Their sounds were linked to the festive, but also to the funereal and even to the conjuration of clouds and plagues. Their use is defined by these Latin phrases: Laudo Deum verum (I praise the true God), plebem voco (I call the people), congrego clerum (I congregate the clergy), defunctos ploro (I mourn the dead), pestem fugo (I drive away the plague), daemonia ejicio (I drive out the demons) et festa decoro (I rejoice the feast). In addition to these canonical uses, we know that they were also used for other more heterodox uses, such as the summoning of councils, auctions and even a rebato to deal with serious contingencies. In some cases, the Visitor could only raise his voice, as in 1625 in Lezáun, when he saw that not even the abbot of the place could stop the custom of call, by ringing the bell, the bringing of the oxen so that the oxen could be grazed by the oxen keeper or boyarico.

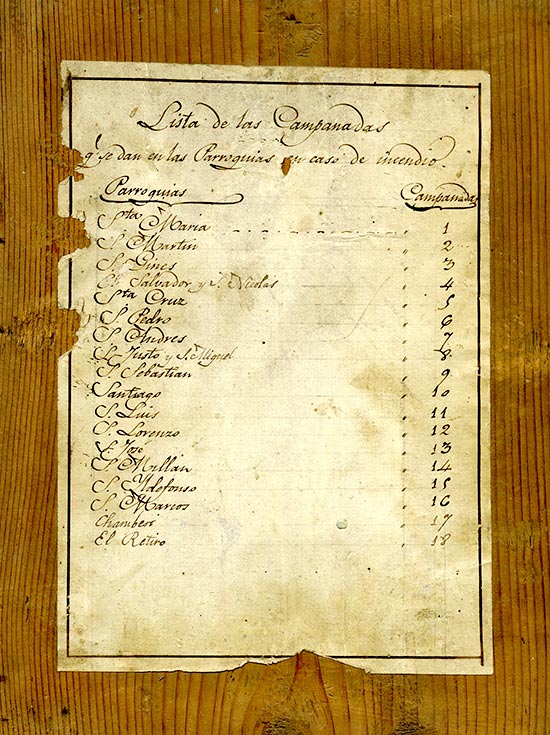

Tablet with a handwritten folio, dating from the early 19th century, which lists the bells that were rung in the event of fire in the parishes of Madrid. Private Collection

In the cathedral of Pamplona, the bell María

The bells of Pamplona's cathedral have been known about since the Middle Ages average and we also know that they took on special significance from the year 1092, when King Sancho Ramírez decided that the towns that saw the mother church and heard its bells should come to celebrate certain special feasts of rogation. The cathedral chroniclers and, especially in the Age of Enlightenment, Don Fermín de Lubián, prior, a diligent, highly educated man with a great knowledge of diocesan and cathedral history, echoed that custom. The aforementioned canon noted in the middle of the 18th century that this privilege was kept unalterably over time, until in the middle of the 17th century, due to the distance, up to fifty localities were freed from this obligation and, later, at the end of the same century, the rest, leaving only the churches of Burlada and Ansoain, which were dispensed by the cathedral chapter "so that in attention to the bad work of their parishioners, they could return before the rogation of the cathedral".

Inside one of its two towers, Pamplona cathedral conserves a bell called the María, made in 1584 by the master builder Villanueva, which is the largest bell in use in Spain. Its clapper weighs 300 kilos and the bell 13,000 kilos. This verse has been passed down from generation to generation:

Maria called me

one hundred quintals weight

and whoever doesn't believe it

take me to the weight

It was built at a time when divine worship was the object of magnificence on the part of dignitaries, canons and bishops. Late chronicles that copied old documentation show that, after being cast on 15th September 1584, the old tower was climbed on 27th October of the same year, in less than three hours, without any misfortune whatsoever.

Bell ringers with the Maria bell in the cathedral on St James' Day 2021. Photo Miguel Bretos

The author of the bell, Pedro de Villanueva, was originally from the town of Güemes, in the Trasmiera merindad, and arrived in Navarre in search of commissions around 1576. He died in 1591, after having worked on "very good and chosen" bells. Since the end of the 16th century, the sounds of the great bell María have accompanied the cathedral ceremonial on the days of great liturgical feasts, processions, deaths of bishops and members of the chapter, as well as other historical events all over the world subject.

To find out more

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "Los trabajos y los días. La campana María", Cuando las cosas hablan. La historia contada por cincuenta objetos de Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2915, pp. 131-135.

URSÚA IRIGOYEN, I., Las campanas de la catedral de Pamplona, Pamplona, Imprenta Zubillaga, 1984.