An allegory of architecture in an academic context: Luquin 1763

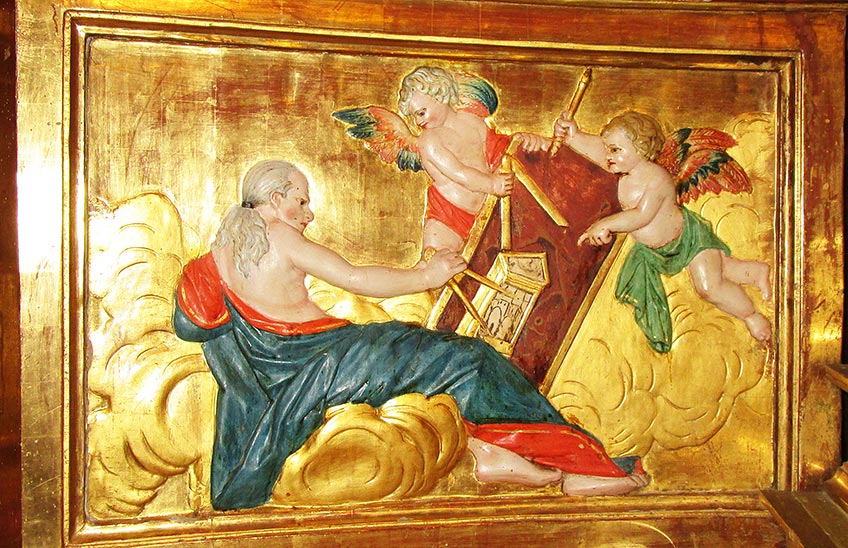

PhotoAlegoryof architecture in a relief of the main altarpiece of Luquin, by Lucas de Mena y Martínez, 1763/.

Truly exceptional in the panorama of Navarrese art from the Age of Enlightenment is the presence of an allegory of architecture that appears in the main altarpiece of the parish church of Luquin. The rarity is even greater if we bear in mind that it is found in a sacred context: the main altarpiece of the parish church. The fact that makes us understand its presence is related to its author, the sculptor Lucas de Mena y Martínez, son and grandson of altarpiece makers, who married the daughter of another artist, Dionisio de Villodas, in 1761, and went to the Royal Academy of San Fernando in Madrid to perfect his art. He enrolled there in October 1762, when he was twenty-five years old. On his return, with a cultural background and new airs, he contracted the Luquin altarpiece at the end of 1763, under the supervision of Silvestre de Soria, a work he was to deliver in 1767. Its architectural lines and the quality of the imagery speak per se of a new style.

On the bench of the altarpiece we find some allegories, with geometry and architecture standing out. The former is accompanied by a globe and compass. The personification of architecture follows the recommendations of Cesare Ripa in his Iconology at design , when he describes her as a woman of mature age with bare arms, accompanied by a compass and square - instruments of geometry - and a parchment on which a plan is drawn. She is also accompanied by two little genies who bring her a pencil-holder, which speaks of the importance of drawing as the father of all the arts, and a square. He explains the age of the personification as "in the maturity of age, the better to show that experience usually coincides in man with the highest Degree of execution of his most ambitious works".

Allegory of geometry in a relief of the main altarpiece of Luquin, by Lucas de Mena y Martínez, 1763. Allegory of geometry in a relief of the main altarpiece of Luquin, by Lucas de Mena y Martínez, 1763. |

The allegorisation is fully in tune with the generalisation of the term "architect" with other connotations than those it had had until then. In Spain, from the mid-16th century, outside the theoretical-artistic context of certain minorities, the architect was a quality assembler, capable of designing and planning an altarpiece, a choir stalls or the façade of a monumental organ. Under the name official document architect, important retablists are documented in all regions who were able to handle the gouge with skill and, above all, those who were able to draw and plan the two- or three-dimensional organisation of altarpieces by means of a design. The production of tracings became so important that Madrid, as the capital of Spain, became a particularly renowned place for their production in the 17th century, given that it was at the Court where the best art was consumed. But it was in the Age of Enlightenment that the discipline of architecture took on a new dimension with the establishment of the Royal Academy of San Fernando. Thanks to the control of the academies, a state architecture was imposed which, in the name of good taste, led to a certain uniformity, and regional peculiarities were also curtailed. The term "architect to the king" was even imposed to replace the old and outdated term "royal master builder".

To find out more

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "En torno a la arquitectura: consideraciones y testimonios de maestros del barroco navarro", Príncipe de Viana, nº 222 (2001), pp. 7-23.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., El retablo barroco en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 2003.

RIPA, C., Iconology, Madrid, Akal, 1996.

MARÍA, F., "El problema del arquitecto en la España del siglo XVI", Academia. bulletin de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, núm. 48 (1979), pp. 173-216.