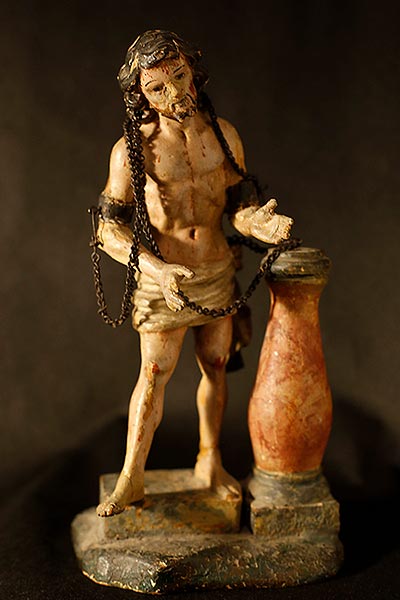

A small sculpture of Christ at the column with Bavarian resonances

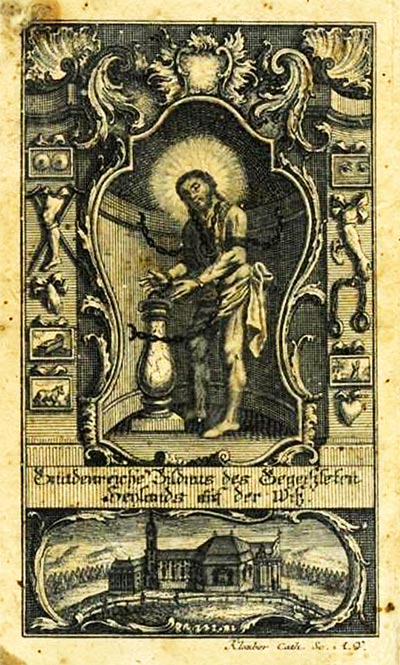

PhotoCedit/Engravedand illuminated print of Christ at the column of the Bavarian shrine of Wies, 1790.

Pass The passage of Christ at the pillar, often glossed in the texts of classics such as those of Fray Luis de Granada or Saint Bridget, which aroused the compassion of the faithful when contemplating a humiliated Christ, bleeding all over his body and accepting suffering, was very popular during the period of Lent and Holy Week.

We know of several small-format images with the topic of the flagellation, but we are going to focus on one from the mid-18th century which, more than for its artistic quality, is A for its iconographic interest. It depicts Christ before a column leave and tied to it by chains that start from his arms to which he is fastened with shackles. With regard to the column leave, there is nothing unusual about a work of this chronology having one, quite the contrary, as from the end of the 16th century the tall column was replaced by another, more reduced in height, related to the one preserved in the church of Santa Praxedes in Rome from the 13th century. This had a more dramatic effect, as the figure lost its point of support and had to hunch over in the face of the lashes which, finding no impediment, would smash the chest and back.

Christ at the column in chains, copying the Bavarian model from the sanctuary of Wies, second half of the 18th century. Photo E. Buxens. Newspaper of Navarre

The chains and rings are even more exceptional, as they lead us to a specific model , which is none other than the head of the Bavarian sanctuary of Wies, an impressive rococo work, built between 1745 and 1754 by the brothers Dominicus and Hojann Baptist Zimmermann, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1983.

The titular image is a touching Christ at the pillar with its own particular history, which dates back to 1730, when the Premonstratensians of Steingaden had an image of the scourged Christ made from pieces of other images and canvases, insisting on the pathetic, with blood and wounds everywhere. After a short time, the sculpture was left without a special cult, until in 1738 the peasant Maria Lory prayed before it and the miracle of Wies occurred, when she felt drops of tears on the face of the image, which led to a great movement of pilgrimages, which made it necessary to build a small chapel that soon proved insufficient to accommodate the pilgrims. As is well known, it is the ropes that take centre stage in the scene of the Scourging, representing Christ's subjection to the pillar, but there were many panegyrists, citing Saint Jerome, who pointed to the presence of chains from the very moment of his imprisonment. The shackles had their point of comparison with those of Saint Peter, preserved in San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, and the chains themselves would be evoked by Saint Basil, when discussing the priest's stole as a reminder of the Passion of Christ. Moreover, for some time and in some circles it was believed and spread that the chains were supposedly kept in Jerusalem with the power to drive away demons that tormented people.

The image of this prototype was widely disseminated through engravings of varying quality, notably those signed by Klauber, and even small sculptures by famous artists such as Franz Ignaz Günter of the Institute of Arts in Detroit, dated 1754, and other much more popular anonymous artists, sometimes with their urns. The fact that it was the object of great pilgrimages favoured this multiplication, in which the chains with the shackles on Christ's forearms and other details such as the bulbous column, the cloth of purity with a hanging part in the upper area, as well as the attitude of the scourged man himself, were never lacking. As in other popular shrines in Europe, prints, medals and reproductions of the sculpture could be acquired on pilgrimage days, making their own particular journey. Some are in museums, such as the sculpture in Detroit, others are in private collections and others are still on sale at auction.

Intaglio engraving of Christ at the column of the Bavarian shrine of Wies, c. 1750 by Klauber.

The image we are commenting on and which has been used for this excursus is one of many that came out of that sanctuary or was made at the request of a devotee in view of its engraved prints. It was probably made in German workshops, from where small polychrome wooden figures intended for nativity scenes were produced in the second half of the 18th century.