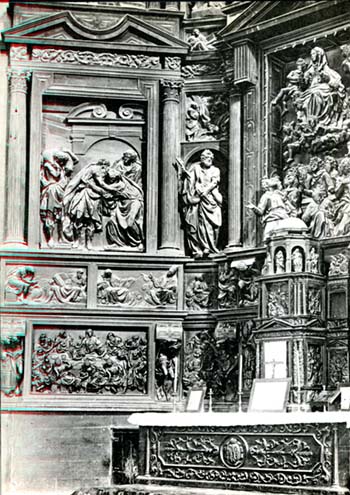

The missing main altarpiece of the Asunción de Cascante, seen by Juan Antonio Fernández in 1787.

Photofrom Georg Weise's 1959 monograph/Performance of the missing main altarpiece of Cascante.

Documents like the one we are about to transcribe for the history of Navarrese art are not frequent. It is neither a contract, nor an appraisal, nor accounts, nor the legal proceedings of a lawsuit. They are historical notes, together with the reflections and judgments of a Navarrese from the Age of Enlightenment, Juan Antonio Fernández (1752-1814), a famous archivist, a man of letters and a connoisseur like few others of the history of Tudela and its merindad.

For one of his works, the Descripción histórico-geográfica de la ciudad de Tudela y de los pueblos de su Merindad (1787), he wrote a text on one of the great Romanesque altarpieces of Navarre, that of the parish of the Assumption of Cascante, which unfortunately disappeared as a result of a great fire in May 1940. The text, dated at the end of the 18th century, is exceptional because we hardly have that subject of descriptions and valuations of outstanding works, prior to the last quarter of the 19th century, a fortiori if the piece has disappeared, as is the case with the Cascante altarpiece.

That altarpiece was, without a doubt, the most expensive in Navarre. Its cost was calculated at no more and no less than the astronomical figure of 7,500 ducats. Its authors were Pedro González de San Pedro and Ambrosio de Bengoechea, disciples of Juan de Anchieta, who contracted it in 1592. Its execution was fixed at deadline in five years. The execution process was surrounded by several incidents since neither Gonzalez nor Bengoechea, willingly accepted Degree to share the business. Once the five years had elapsed, the altarpiece was not finished, which gave rise to a litigation process in the Navarrese Royal Courts. Finally, the work was finished in 1601.

Detail of the main altarpiece of Cascante. Photo Mas (1916). Photo library of the file General of Navarra

Juan Antonio Fernández's text is a son of those years, when academicism prevailed and the neoclassical taste was definitely imposed. From his reading it can be inferred that he knew the volumes of the Viaje de España by Antonio Ponz, secretary of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, to whom quotation was an authority. The historical and iconographic reading data are accurate.

Among the concepts he handles are those of correctness, good taste, delicacy, elegance, truth and beauty in the formal aspect, and propriety in the historical aspect. All of them are in line with the appraisals widely used in the artistic literature of the time and in the correspondence of academics.

From the content of the text we have to emphasize the news that contributes on the existence of a wooden model made for the main group of the Assumption of the Virgin, that Francisco de Villanova owned and that, unfortunately, it has not been possible to locate. This last personage belonged to a noble lineage, was mayor of the city, was born in 1743 and died in 1801, being buried in the Victoria. One of his daughters, María Antonia, married Francisco González de Castejón y Veráiz, mayor of the Court of Navarra.

Juan Antonio Fernández regrets in his text that the final result in the Assumptionist group was not adapted to the aforementioned model , much more appropriate in its forms, for the purpose pursued in that passage.

The photographs we know of the piece were published by Professor Georg Weise in his work on Renaissance and early Baroque art (Tübingen, 1959).

A couple of evaluations of the illustrious tudelano

His appreciation of the inadequacy of the passage of the Embrace of St. Joachim and St. Anne, as a prefiguration of the Conceptionist mystery, must be interpreted in the light of the iconographic criticism of some authors. It should be remembered that, until well into the 16th century, it seemed that topic of the Embrace was the one that represented the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. However, the scene did not lend itself, with its naturalism, to visualize an abstract idea. The kiss signified the beginning of the Virgin's conception and led theologians to search for other more ad hoc representations. Velázquez's father-in-law and teacher, Francisco Pacheco, in his Art of Painting, wrote about the convenience of banishing the idea transmitted with that iconography, since some interpreted "that by that kiss, without any other means, the Virgin Our Lady was conceived". The topic of the embrace of Joaquín and Ana in front of the Golden Door began to be less and less used to represent the Conceptionist mystery until it was formally prohibited in 1677 by Innocent XI.

Embrace before the Golden Door of St. Joachim and St. Anne of the disappeared main altarpiece of Cascante. Photo from Georg Weise's monograph of 1959.

As for the final paragraph of Juan Antonio Fernández's text, where he congratulates himself on the fact that the work remained unpolychromed, it is also appropriate to reflect on the reasons he gives: "plaster and brush would put a veil that would obfuscate the most of its beauty and muffle the expression". Undoubtedly, in a century like the 18th, of revaluation of the plastic arts and the use of unpolychromed marble, the reasons were extrapolated to polychromy, at a time when the all-out war against gilded wood altarpieces and, by extension, the typically Spanish genre of polychrome sculpture, was a fact.

The exceptional text by Juan Antonio Fernández

"The main altarpiece is one of the works that by its design has attracted the attention of the friends of beauty. The expression in countenances, actions and postures, correctness in the nude, ease and docility in every place, propriety in the story, everything is found in this monument of the Fine Arts, worthy of the time of the Becerras and Berruguetes and that can compete with the best that has been manufactured after the introduction of good taste. To confession of intelligent in subject of sculpture, it takes many advantages to the one of Tafalla and to the ashlar of Pamplona, works of the immortal Ancheta, so celebrated of don Antonio Ponz .

We will try to make as brief as possible a description of this treasure of beauty. The altarpiece has three architectural bodies. In the main one of Corinthian order are the stories of the Assumption, conception and birth of the Virgin, all larger than the natural; in the intercolumniations St. Peter and St. Paul; on them, on boards their martyrdoms. In the second, which is of composite order the stories of the coronation of the Virgin, presentation in the temple by her Fathers and Assumption, all natural; in the intercolumniations St. John and the Magdalene. In the upper body, supported by botantes Jesus Christ, crucified with Mary and St. John, the circumcision of the Child God and the visitation of Our Lady; in the niches San Diego and San Roque.

group of the Assumption from the disappeared main altarpiece of Cascante. Photo from Georg Weise's monograph of 1959.

The tabernacle is the best and most delicate thing it has. It is reduced to a templete of three bodies, very proportionate, with the stories of the crucifixion of the Lord, Holy Burial and others of the passion. The pedestals of the whole work are between shelves or cartons supported by angels; in the middle are two stories, the legal Supper and the Arrest of the Savior, all arranged with the greatest elegance and naturalness, and in the recessed several stories of half relief.

The architecture is made of pine, the sculpture of strong walnut, from Montaña.

There are also two side altars of the same quality and hand with four stories on boards each and two statues of natural in niches. Their dedications are of the first one of Santa Ana and San Joaquín, of the second one San Lorenzo. The panels of the latter contain the martyrdoms of the saints and those of the former those of the Resurrection, Birth, Assumption of the Lord and Coming of the Holy Spirit.

The statues of the intercolumniations are of the most correct and expressive. The Magdalena stands out, a truly real statue (ideal) and St. Paul with all the authority of an apostle of the people. St. Roch and St. John are remarkable for their expression and truth. The panel of the Annunciation and that of the Birth of the Virgin are remarkable for their drawing and beauty of contorneries and for the characters so appropriate for a story of this nature. Generally, the side of the Epistle is better worked and more correct than the opposite and the opposite side.

It is a known fact that the authors of this work were Pedro González de San Pedro, neighbor of Cabredo and Ambrosio de Bengoechea; that the work was begun in 1593 and that by May 1601 it was already being placed. It was all adjusted at 7,500 ducats, five hundred more or five hundred less according to the law of appraisal. All this is recorded in several requirements made to the existing sculptors in the file Parroquial.

At the time of the placement of the altarpiece, the primicieros complained to the artisans that the altarpiece was not executed according to the plan and that many of the figures were improper and imperfect. And indeed, along with so many beauties, there are absolutely insufferable things. The figure of the conception of the Virgin in an amplex of the grandparents of Christ is either indecent or exposed to error. The body in front, which is the one that should show off the most, contains many imperfections: the Assumption and the sepulcher with the apostles, although it is a very proper composition and of great study, is not made according to the plan that is seen in a little wooden model that Don Francisco Villanova has in which Mary Most Holy has another more graceful and sovereign attitude in her arms; the arch is much more raised and leaves room for the flight and the main figure of more body and floating clothes. If it were executed it would deceive the sight, seeming to ascend Mary to the heavens with all the sovereignty of a Mother of God.

In the story of the Coronation of Mary Most Holy, which is in the second body opposite, the optical proportions are so poorly kept, because of the disproportionate and oppressed figures that it seems they have been forced into the niche, and the Holy Spirit is represented in the form of a vulture. In the Prendimiento there is a dwarf figure of St. John; the panel of the Prayer in the Garden (although it is hidden) is totally imperfect.

This shows that Pedro González, engaged at the same time in many works, and more attentive to interest than to glory, did not do all the parts by himself. There is an injunction that was served on him in Pamplona to return to Cascante, not to engage in new works and to execute the altarpiece on his own in 1596.

It is unpainted and we believe that Gonzalez's invention was to keep it that way. The plaster and the brush would put a veil that would obfuscate the most of its beauties and would muffle the expression".