San Sebastian, advocate against the plague

PhotoJ. L. Larrión/Tablet of Saint Michael and Saint Sebastian from the Burlada altarpiece -today in the Museum of Navarre-, by Juan del Bosque, 1540-1546.

Saint Sebastian was a Christian soldier of the Imperial Guard in the 3rd century. One of his companions denounced the young man's beliefs to an officer, who did not dare arrest him because of his high rank, although he put him on knowledge to the Emperor. The emperor - traditionally identified with Diocletian - sent for Sebastian and reproached him for his ingratitude in introducing a religion he considered harmful to the empire. Sebastian was not deterred and replied that no better service could be done than to convert his subjects to the religion of Christ. Irritated by this reply, he ordered him to be tied to a log and sawn to death. He was left for dead, and a holy woman, named Irene, went to bury him and found him alive, taking him home to dress his wounds. On hearing of this, the emperor ordered him to be taken to the circus and beaten to death.

Plague Lawyer

Beliefs in the protection of the saints at momentous times of illness and death developed their role as intercessors and thaumaturges and were expressed in hagiographic texts and visual representations. The case of Saint Sebastian, as an advocate against the plague, is illustrative, as was the case with Saint Roque from the 15th century onwards.

The origin of Saint Sebastian's protection from the plague dates back to the year 680, when he freed Rome from a great epidemic, a fact reported by Paul Deacon in his Historia Longobardorum. At the time, it should be remembered that the plague coincided with a rain of arrows, both in classical sources - a passage from the Iliad in which Apollo unleashes the plague with the shot of his arrow - and in biblical sources (Psalms 7 and 64). The Golden Legend played a decisive role in the spread of his cult and iconography. In its text it is stated that the saint was left like a hedgehog after his asaeteamiento. From the middle of the 14th century, during the Black Death, his popularity grew enormously.

By the end of the Middle Ages, average, he had become the martyr saint par excellence, with great notoriety throughout Europe. The parallels with Christ were glossed over, not only because of his relationship with the passage of Christ tied to the pillar or with the Ecce Homo - in the case of appearing with his arms forward - but also because of the tree to which he was tied in analogy with the wood of the cross and because of the symbolic issue of his arrows. issue If there were three of them, they evoked Christ's nails, and if there were five, they evoked his wounds.

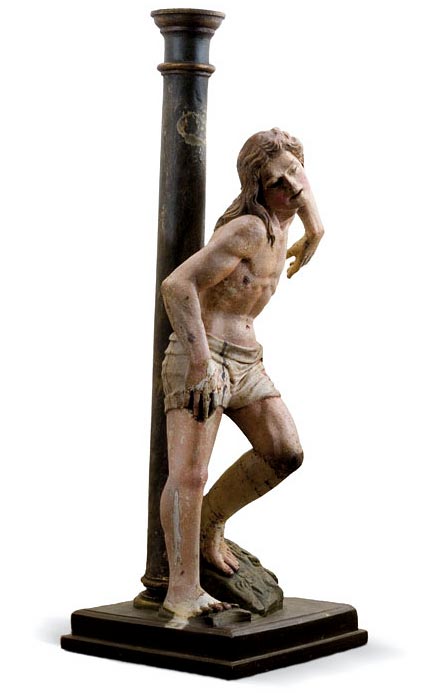

Image of Saint Sebastian from the monastery of Fitero, an Aragonese work from the mid-16th century. Photo J. L. Larrión

From the Middle Ages onwards, the municipal authorities of towns and villages made vows to the saints, which were translated into promises to keep their feast days, in gratitude for favours received. They were very frequent and some towns had several, as was the case in Pamplona and Sangüesa, with eight and six respectively.

One of the first documented vows to Saint Sebastian in Navarre is that of Olite, in 1413, as a result of the plague of that year. Some of those vows ended in the patronage of certain towns. In Tafalla, the legendary miracle of the beret in 1426 led to the growth of his cult, with numerous donations coming through his confraternity. Its famous stone image is attributed to the sculptor Johan Lome and in 1422, the royal secretary Sancho de Navaz left a commission for its creation.

An extensive and documented study on the patron saint of Sangüesa is by Juan Cruz Labeaga. The vow was already being celebrated in 1543, before the great plagues of 1566 and 1599. The town council appointed the preacher for the festival and the annual procession was attended by all the guilds.

Iconography: predominance of the martyr figure

Artistic representations of Saint Sebastian are very abundant in Navarre, the most common being those depicting him as a young, naked, beardless boy tied to the trunk of a tree or a column. The very position of the martyr allowed artists to study the human body strained by a forced position, as well as to express everything related to pain, agony and ecstasy.

A number of sculptures have survived from the Gothic period or with the imprint of its aesthetic. The polychrome alabaster image in the cathedral of Tudela, a work attributed by C. Lacarra and S. Janke to the master Hans Piet d'Anso or Hans of Swabia, sculptor of the altarpiece in the Cathedral of Zaragoza and resident in that city between 1467 and 1478. Heirs to the Gothic aesthetic we find some images in Navarre around 1500, among which those of Muniáin de la Solana, Asarta and Villafranca stand out.

Sculptures and reliefs of the saint in the Comunidad Foral multiplied throughout the 16th century. There is no doubt that the model of the naked young man lent itself to recreating the human body, albeit a suffering one, in the context of Renaissance humanism. His representation was an excellent excuse for many masters to show a naked male Anatomy without fear of ecclesiastical censorship, in times when decorum was a rule and artistic principle.

On some occasions, the isolated figure is accompanied by executioners with bows and even crossbows.

Preparations for the asaeteamiento of Saint Sebastian by Pedro Ibiricu, 1687. Parish church of San Pedro de la Rúa in Estella. Photo J. L. Larrión

To find out more

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "San Sebastián, protector against the plague, in the heritage of Navarre". Diario de Navarra, 13 January 2017, pp. 64-65.