Saint Benedict in a cycle of paintings in the monastery of Fitero

Saint Benedict (480-547), patriarch of monasticism and author of the most important monastic rule in the West, is the founder of the Benedictine order, so closely linked to Christian Europe since the Middle Ages average. His person and work are best known through the Dialogues of St. Gregory the Great, which present him as model of continuous asceticism towards perfection, overcoming the passions and temptations of vainglory, lust and anger. His motto of ora et labora is complemented by charity and humility, so present in his rule. The latter would be taken up again in the 9th century by Benedict of Anianus, codifying it and making its great expansion possible. Later on, in the middle of the Age average, it acquired enormous importance, thanks to Cluny and the centralisation of the monasteries, having been fundamental in the spread of the Gregorian reform. His feast day has traditionally been celebrated on 21 March, with the arrival of spring, although after the liturgical reform, it was moved to 11 July. Paul VI affirmed that his sons had carried "with the cross, the book and the plough, Christian civilisation" when he declared him patron saint of Europe in 1964.

|

|

|

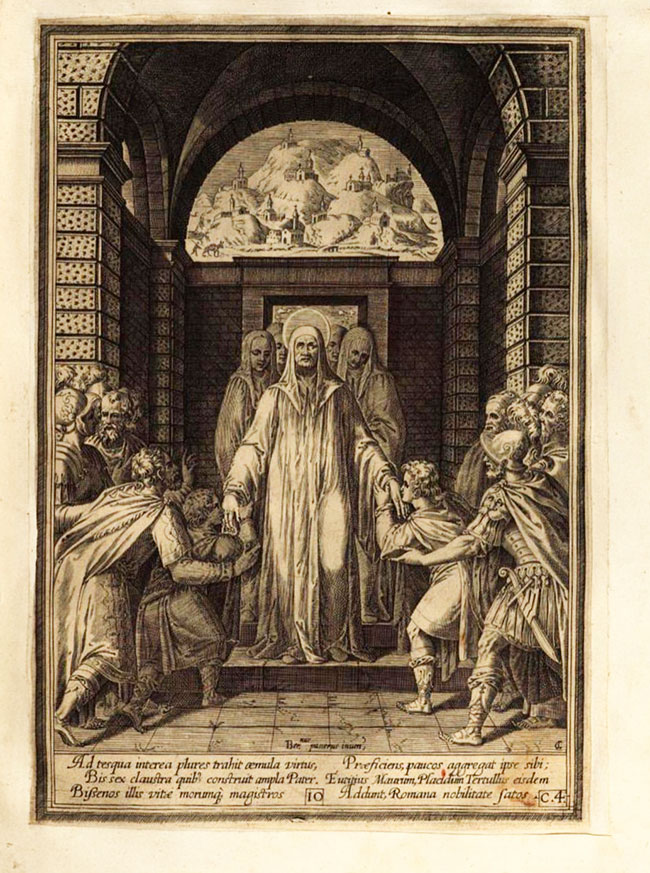

| Engraving of the presentation of Mauro and Placido by their fathers Evicio and Tertulo to Saint Benedict, by Aliprando Capriolo (Rome, 1579) which served as model for the same topic, painted on panel, on the altarpiece of the saint in the monastery of Fitero, c. 1614. | |

The iconographic prototype of the figure of Saint Benedict is very simple. He wears the large black cowl of a Benedictine monk, usually carrying the crosier - the abbey emblem par excellence - and other insignia of his dignity: mitre and pectoral. He is usually bearded and also beardless, with a wiry face and a cheerful look, from agreement with a widespread custom in the Congregation of Saint Benedict of Valladolid. As attributes, he usually carries the book of the rule and, more exceptionally, the cup that recalls the drink with which they wanted to poison him and the crow with the poisoned bread in its beak. Several paintings and sculptures of great quality are preserved in Navarre.

|

|

|

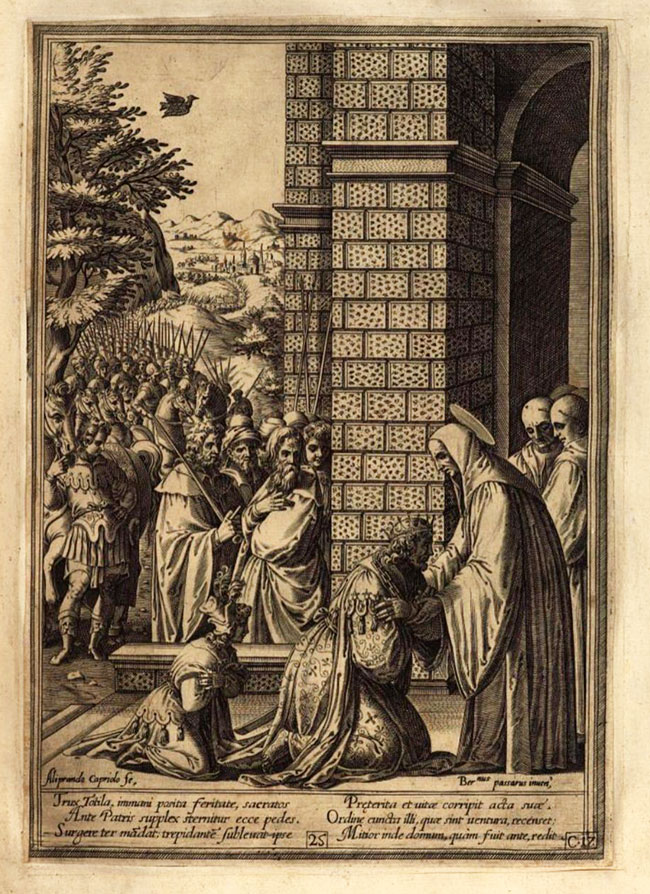

| Engraving of the false king discovered by the saint, by Aliprando Capriolo (Rome, 1579) which served as model for the same topic, painted on panel, in the altarpiece of the saint in the monastery of Fitero, c. 1614. | |

A unique cycle in Navarre based on Roman engravings

The altarpiece of the saint in the monastery of Fitero (1614-1615) has a small series of four mediocre paintings, but they are interesting because they are the only Benedictine cycle preserved in the Comunidad Foral. As on other occasions, the painter-polychromator of the altarpiece excelled in the decorative work and the stuccoes, but the easel painting surpassed him, despite having had the specific models at hand, probably provided by the monks of the abbey.

degree scroll The graphic sources for all of them are to be found in the illustrated life of the saint, which was published in Rome in 1579 under the title Vita et miracula Sanctissimi Patris Benedicti, with engravings by Aliprando Capriolo Trentino, with models by the Roman painter Bernardino Passeri. The business publishing house was made possible by the procurator general in Rome of the Congregation of St. Benedict of Valladolid, Fray Juan de Guzmán, and was reprinted in 1584, 1594 and 1597.

|

|

|

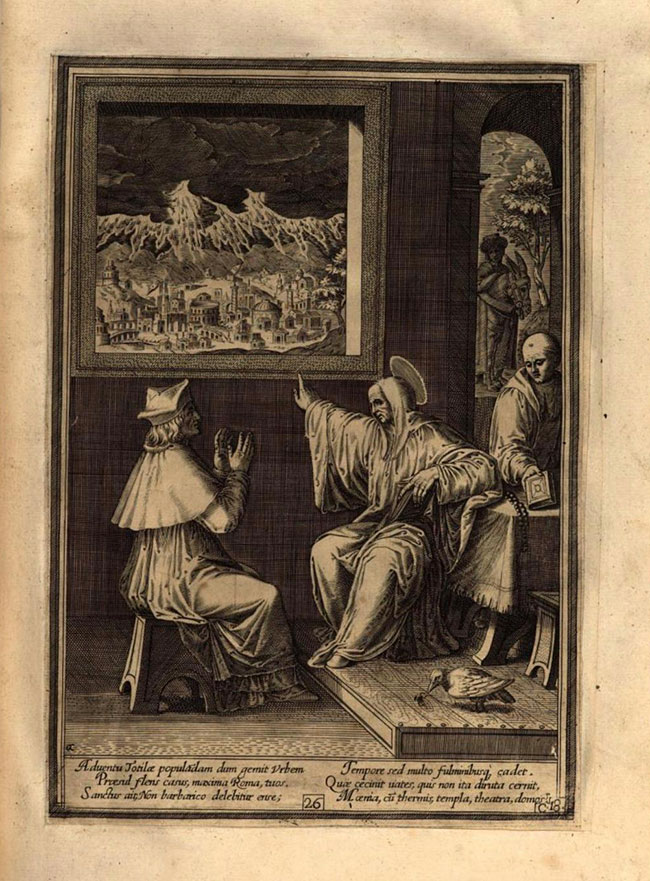

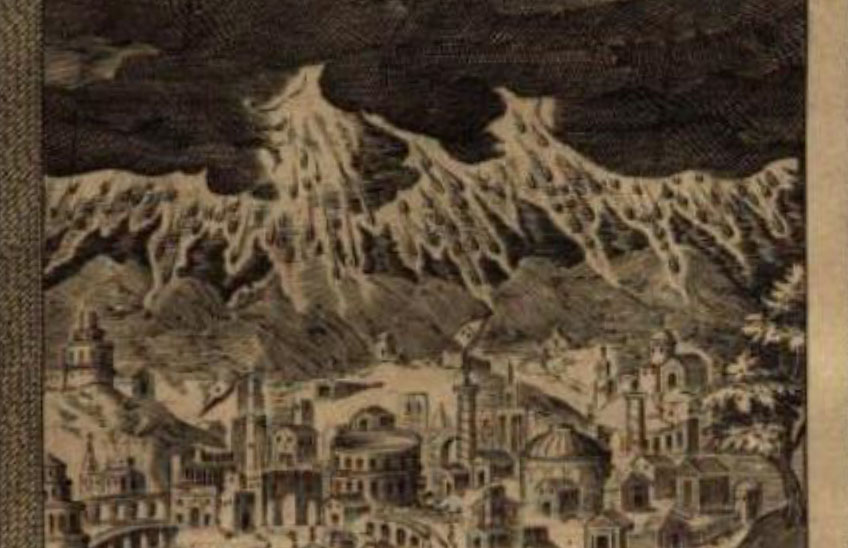

| Engraving of St. Benedict with Totila, by Aliprando Capriolo (Rome, 1579) which served as model for the same topic, painted on panel, on the altarpiece of the saint in the monastery of Fitero, c. 1614. | |

Those prints were used to make the backs of the choir chairs in various Benedictine monasteries. In fact, at least three of those that inspired the Fitero panels can be found in the choir stalls of the monasteries of Veruela, San Martín Pinario, Celanova and San Benito in Valladolid.

The first scene narrates the presentation of Mauro and Placido by their parents Evicius and Tertullus to Saint Benedict so that they could be educated under his jurisdiction, given his growing reputation for virtue. At the time, it should be remembered that as his reputation for sanctity grew, disciples were entrusted to him, and he was obliged to found monasteries and to take under his spiritual guidance various Roman nobles. The topic can be found in Veruela and the seats of San Martín Pinario, Celanova and San Benito in Valladolid.

|

|

|

| Engraving of Saint Benedict and Saint Sabinus, by Aliprando Capriolo (Rome, 1579) which served as model for the same topic, painted on panel, on the altarpiece of the saint in the monastery of Fitero, c. 1614. | |

The second and the third refer to the relationship between Saint Benedict and the barbarian king Totila. In the second, the aforementioned monarch wanted to put the saint's divinatory powers to test and after announcing his arrival, he ordered his servant Rigo to dress up in royal regalia. When Saint Benedict saw him, he ordered him to take off his royal regalia, but the mocker was mocked. The passage can be found in the choir stalls of San Martín Pinario, Veruela, Celanova and that of the laity of San Benito in Valladolid. The third is a continuation of the previous one and narrates the meeting between the abbot and the king. The latter prostrated himself, asking forgiveness for his evil deeds, and the saint warned him about his future, before which he asked for forgiveness and withdrew. The scene can be found in San Martín Pinario and the high choir stalls of San Benito in Valladolid.

The fourth and last tells of the meeting between St. Benedict and St. Sabinus, as St. Gregory recounts in his Dialogues, in this text: "The bishop of the Church of Canosa used to visit the servant of the Lord, and the man of God felt a special affection for him because of his virtuous life. During a conversation about the entrance of King Totila in Rome and the devastation of the city, the bishop said: "This king is going to destroy the city in such a way that from now on it can no longer be inhabited". To which the man of God replied: "Rome will not be exterminated by the barbarians, but will be consumed in itself, devastated by storms, hurricanes, cyclones and earthquakes". The painting is characterised by the rough view of Rome, executed as a painting within a painting.

To find out more

GONZÁLEZ DE ZÁRATE, J. M, "Aportaciones del coro alto de San Benito de Valladolid a la iconografía de San Benito", bulletin del seminar de Arte y Arqueología de Valladolid, t. 52 (1986), pp. 357-368.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., "Heritage and identity (29). San Benito en el patrimonio navarro", Diario de Navarra, March 20, 2020, pp. 56-57.