Reading in the Nativity Scene: some symbolic aspects (I)

FotoCedida/Birthin Murcian polychrome clay figures from the end of the 19th century from the old Dominican convent in Tudela.

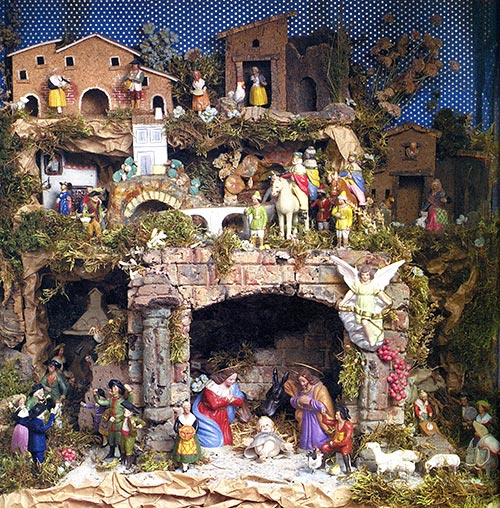

If we visit a modern-day nativity scene, we will find delicate three-dimensional representations of the birth of Christ to scale, with frequently orientalist architecture and figures of a supposedly historicist style. However, until a little over a century ago, the traditional nativity scene was based on other assumptions: portal with classical ruins, large rocks and crags and figures dressed according to the customs and traditions of different regions.

The great change, with respect to the figures, took place at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the last century, when the Church and the nascent Associations of Nativity Scene Makers - especially the Catalan ones - promoted the creation of a new style. From then on, the old polychrome clay figures, made in the workshops of Murcia or Granada, exponents and synthesis of a centuries-old tradition, began to decline. All this was favoured even more by some directives that, after the Civil War, were addressed from the Spanish Falange to the nativity scene makers and their associations in order to banish the anachronisms of the popular nativity scene.

There were a number of reasons behind these innovations. Firstly, the Church's custom of not blessing clay images. The new figures of the Olot school were made of wood paste and had a dignified appearance and, above all, a pretended historical fidelity, as the figures were dressed in timeless attire. Precisely because of its propriety and historicity, Olot's aesthetic captivated personal clients and institutions with its particular historical vision, derived from the group of the Nazarenes, German painters who reacted against the prevailing Neoclassicism on the basis of archaeological discoveries in Palestine. In the same vein, the artists of the Parisian street of Saint Sulpice had a decisive influence in Catalonia on the Olot school with a correct, somewhat sweet style influenced by the Nazarene school. With these budgets, parishes, convents and schools, as well as amateurs, opted for these figures, standardising everything related to the nativity scene, always from an orientalist perspective. For the time being, the figures from the Olot workshops coexisted with the traditional terracotta ones, but they would eventually prevail over the latter, which also underwent their own evolution to adapt to fashion with tunics, cloaks and turbans, which would eventually incorporate glued fabrics.

Large display case with nativity scene made up of Murcian figures from the late 19th century: Private collection.

In contrast to the panorama of the last hundred years, dominated by historicism, ancient nativity scenes were much more symbolic in all their elements, since in an illiterate society it was easier to catechise through simple messages than to speculate on the reality of 1st century Judea. It was not so much a matter of conjecture, or of organising perspectives and scales, but of conveying messages about the ineffable, by means of ideas.

The cave and its characters

If classical ruins were placed in the cave, it was to signify that the coming of Christ surpassed the Old Testament. If rocks and boulders were placed in the cave, it was to insist that the birth of the Saviour took place among beasts, in a cave, outside the inhabited place, after the Holy Family had been rejected by the people. All this gave rise to reflections on how Jesus could be expelled from the hearts of men. Candles and lanterns were placed next to portal and the floor was strewn with crushed glass and shells to reflect the light, since nativity scenes were designed to be admired at night, to be approached with the senses and the spirit to contemplate the "light of the world".

The figures of Joseph and Mary were dressed in precise, symbolic colours. She wore red or pink in her tunic, to indicate the colour of the flesh due to the Incarnation, and blue in her robe, which identified her as the queen of heaven. Often the robe was white, to show her purity. Joseph, on the other hand, combined the purple of suffering and sacrifice with brown, the colour with which carpenters were identified. Sometimes he wore a yellow cloak, because he belonged to the Jewish people. Ordinarily, and following the recommendations of Saint Bridget's visions, both were before the Child "kneeling on their knees, they adored him with immense joy and gladness".

Virgin and Child with sash from the Mendigorría nativity scene, by Juan José Vélaz, 1825, now in the Diocesan Museum of Pamplona.

The Divine Infant was of large proportions, in keeping with the old rules of hierarchical size, and was usually in a cradle of Trinitarian content, as it was adorned with a triangle and the Dove of the Holy Spirit, together with a glory of angels' heads. On some occasions the Child appears with a sash, from agreement with a custom still present in some Latin American countries. This is mentioned in the documents of the "belenera" of the Augustinian Recollect Nuns of Pamplona and was sculpted in the nativity scene of Mendigorría, the work of Juan José Vélaz in 1825.

With regard to the animals, the mule is identified with the Jewish people, hence in some cases it appears kneeling before the mystery, giving way to the New Law, while the ox is assimilated with the pagans and gentility.

Mule worshipper in polychrome wood, 18th century. Private collection

The water of the river or of the source also had a symbolic content, since where there is no water there is no life. The birth of Jesus became a real source of life.

To find out more

ARBETETA MIRA, L., "Metodología y cuestiones previas para el estudio de los Nacimientos españoles", Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares, t. 48 (1993), pp. 169-212.

ARBETETA MIRA, L., Oro, incienso y mirra. Nativity scenes in Spain. Madrid, Telefónica. Fundación Germán Sánchez Ruipérez, 2000.

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., A Belén pastores! Belenes históricos en Navarra, Pamplona, Government of Navarre-Pamplona City Council, 2007.

PEÑA MARTÍN, A., La Navidad en España en el siglo XIX. El Nacimiento y sus tradiciones, A. Peña Martín, 2016.