Cultural heritage and identity

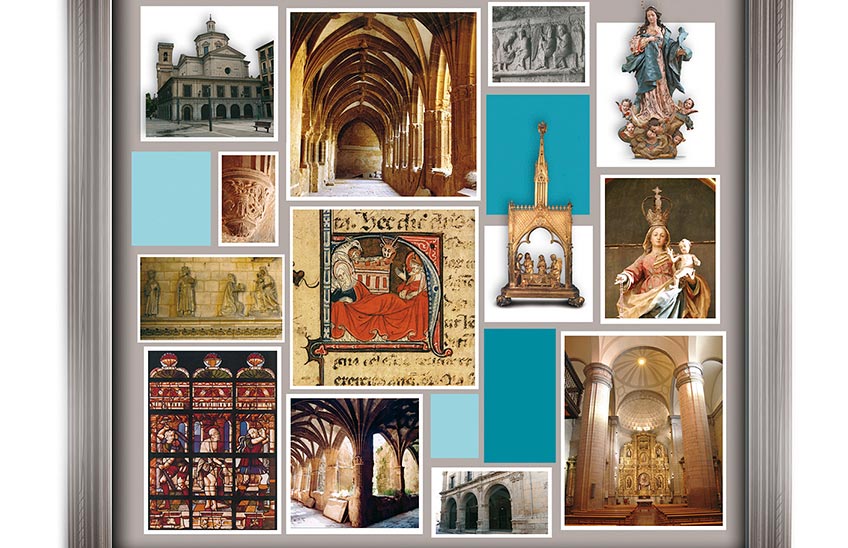

FotoCedida/Coverpageof the report of the Chair de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro (2008)

It is not advisable to take texts out of context, as they run the risk of becoming pretexts. But I will start with a suggestive degree scroll that I. Gabilondo used for one of his journalistic collaborations: "A society without common ground is a society without common sense". It is very useful for reflecting on cultural heritage as a sign of common identity and an element of cohesion and structuring of our towns and cities.

Recently, 2018 was declared the European Year of Cultural Heritage, with the goal to encourage discovery and engagement with the rich heritage received from our elders, reinforcing the feeling of belonging to a common space. The motto adopted was "Our heritage: where the past meets the future".

Heritage, tradition and identity are three concepts that are related but have their own sphere. Heritage, tangible and intangible, constitutes the expression of the culture of a human group and establishes a link between generations. By tradition we mean what has been handed down to us from the past, although it must be borne in mind that it is not immobile and unalterable, but dynamic, changing and adaptive. Identity refers to tradition and heritage, always bearing in mind that human beings are gregarious and seek coincidences, in order to feel like members of a collective, developing a sense of belonging.

The identity of our peoples linked to their heritage

The cultural identity of a people is defined through multiple aspects in which its culture is embodied, such as the historical-artistic bequest , the language, social relations, rites, ceremonies, social behaviour and other immaterial elements. Monuments and objects are specifically effective as condensers of values. Because of their material and singular presence, as concrete cultural assets, they have a high symbolic meaning, which they assume and summary the essential character of their historical context. Cultural assets help to deepen the history of peoples and outline their own identity, staff and collective.

The concept and idea of heritage took shape in the 19th century, after the experiences of destruction caused by wars and revolutions, which made many traces of an abhorred past disappear. A circular of the French National Convention of 1794, after the multiple destructions, recalled: "You are only the depositaries of the property donated to the great family, which has the right to ask you for an account. Barbarians and slaves detest science and destroy artistic monuments. Free men love them and preserve them". In Spain, after the disastrous consequences of Mendizábal's Disentailment, provincial Monuments Commissions were soon set up to try to stop a catastrophe of movable and immovable, bibliographical, musical and documentary heritage.

By appreciating our cultural heritage, we can discover our diversity and initiate an intercultural dialogue on what we have in common with other realities. In this regard, nothing better than to recall this reflection by Mahatma Gandhi: "I do not want my house walled in on all sides or my windows sealed. I want the cultures of the whole world to blow into my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be swept away by any of them".

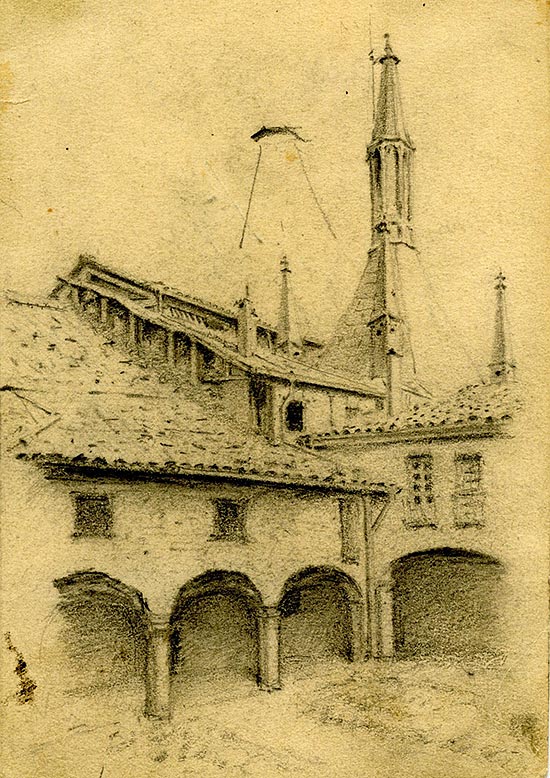

Pencil drawing of the archdeaconry of Pamplona Cathedral, early 20th century. Private Collection

The past of a town and its heritage belong to all its inhabitants.

In the presentation of this blog, we recall the reflection of Julio Valdeón when he reminds us that the history of a town belongs to all its inhabitants and constitutes the best support for knowing where we are heading. If this past is linked to material testimonies, the collective conscience will be much stronger. Alex de Tocqueville expressed this idea with this thought: "If the past no longer illuminates the future, the spirit walks in darkness". Octavio Paz stated that "architecture is the least bribable witness of history" and Francisco Umbral wrote that "painting is the great blackboard of history". These last two thoughts can be extrapolated to the rest of the arts and cultural heritage.

Losing the references of the past is tantamount to erasing the path and favouring disorientation. Faustino Menéndez Pidal recalled in one of his reflections that "the people who do not know their past, who ignore the ways by which they came to be where they are and to be what they are, are at the mercy of those who want to show them a falsified history for sectarian ends. The installation in history is man's most solid base, because it conditions all the Structures that situates him in society. When he loses it, he is left without roots, deprived of elements of judgement and choice". source In this respect, it should be borne in mind that history and heritage itself have also been used by political power on numerous occasions as a means of legitimisation and justification, as the past is often rewritten according to the needs and interests of the moment.

The monuments, artefacts and objects we have received defy time, constitute a gateway to the past and are a form of journey through history that, on many occasions, entail something transcendent. Without all these testimonies of the past, the citizen runs the risk of getting lost in a world lacking in tangible references, where the present can seem eternal. Contemplating, thinking and reasoning about cultural assets financial aid to understand the past, to live in the present and to project oneself into the future without complexes.

Historical heritage, as the most important testimony of the cultural identity of a people, is a non-renewable wealth and constitutes a solid test of the existence of links with the past because it constitutes the report on which one has to reconstruct one's own history. J. A. Alzate wrote in Mexico in 1790 the following reflection: "the architectural monuments of ancient nations which remain, in spite of the injuries of time, serve as a great resource to recognise the character of those who built them..., as well as to make up for the omission or bad faith of historians".