Burials, Offerings and Suffrages: Graphic Testimonies of a Lost Religiosity (I)

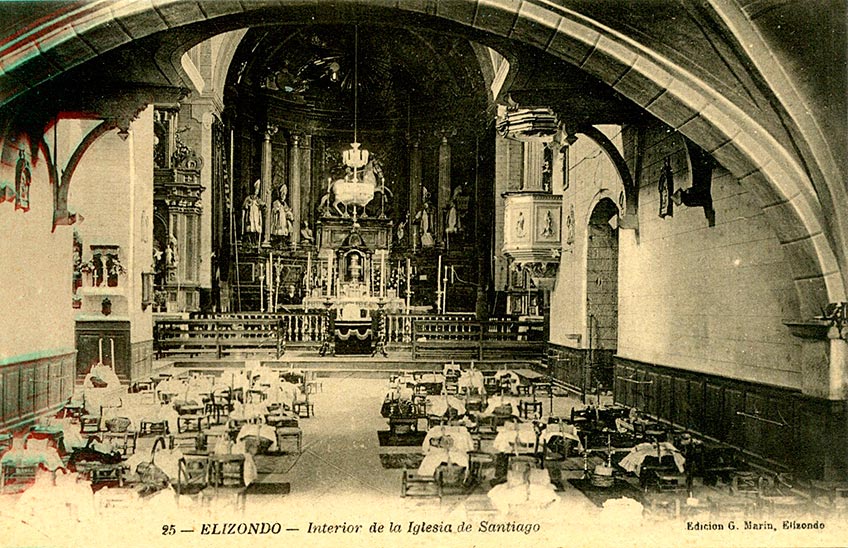

PhotoPostcardmarketed by G. Marín de Elizondo/Interior of the old parish church of Elizondo on All Souls' Day, at the beginning of the 20th century.

The custom of burying bodies by Christians dates back to the first centuries of our era, when they opted for the burial of bodies, as opposed to the Roman custom of cremation. At first, they did so in the gardens of the houses of certain faithful, then in the catacombs and, later, in stone sepulchres.

During the Middle Ages, average, it was widely believed that the bodies of those buried inside churches benefited more from the liturgical services celebrated in them and, therefore, attained divine forgiveness sooner. This is why the tombs closer to the altar were more valuable than those further away.

The Partidas of Alfonso X Wise established in Castile which persons could be buried in churches: "kings and queens and their fixed ones, and the bishops and abbots, and the priors and masters and the commanders who are perlados of the conventual churches, and the rich ommes and the other ommes onrados that fiziessen new churches or monasteries and scogiessen in them their sepulchres; and all other omme quier fuesse member of the clergy or layman, that they put it by sanidat of good life and of good works".

The interiors of the parish churches had their own plan of family tombs or boxed sepulchres which, in many cases, have been preserved or are known to us by design. Other cemeteries located in the atriums or next to the temples have interesting funerary stelae bequest .

Corresponding to the different periods, we find as many discourses, symbols and images next to the most important tombs, in some cases with classical motifs that allude to immortality, in others with numerous reminders of the vanity of earthly things and in others of the resurrection of the dead and eternal life. In most of them there is no lack of heraldry as a sign of the lineage's identity.

The celebration of All Souls' Day or All Souls' Day was important because it was prescribed that, from noon on 1 November, the feast of All Saints, to the evening of the following day at average , with certain prayers, responsories and the petition for the intentions of the Roman Pontiff, a special indulgence was gained, applicable to the souls in purgatory.

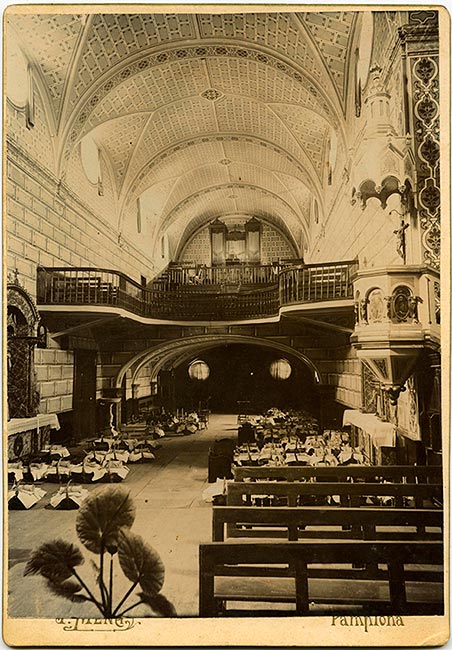

Two interiors of churches in Baztanes on the day of Ánimas

The snapshot captured on a postcard marketed by the local establishment of G. Marín de Elizondo at the beginning of the 20th century, sample shows what the inside of the parish church looked like on the day of All Souls' Day or its novena, with everything ready to sing the response with absolution to the catafalque, the piece we see in front of the altar, next to the communion rail. But it is the entire floor of the nave of the church, from the undercroft onwards, which is striking because it is covered by family tombs with offerings of candles and loaves of bread. As is well known, in traditional society, the burial place was considered an extension of the native house. It was located in the church and was known by the names of fosa or fuesa. The aforementioned offerings were placed on the grave, covered with a cloth for the dead, usually black, on top of which there was a support for candles or axes, or for the match twisted into the argizaiola, a basket and a kneeler. The postcard belongs to a series from the locality and must be dated, of course, before the construction of the new parish church in 1916, perhaps as much as average a dozen years earlier.

|

|

|

Interior of the parish church of Arizcun on All Souls' Day, 1924. Photograph by Félix Mena. |

The photo library of the file General of Navarre has a high quality photograph of the parish church of Arizcun, seen from the presbytery towards the foot, on the same dates in November. It is a snapshot taken by Félix Mena. On the front it bears the following inscription: registration: "F. Mena - Pamplona". On the back: "PHOTOGRAPH OF F. MENA. AWARDED WITH A GOLD MEDAL. Calle Mayor, 86. FLOOR leave. PAMPLONA". The photograph is interesting not only because it shows us the church on a day of services, but also because it is taken at a time before the latest alterations that eliminated the lateral wings of the choir and tore out the original oculi to convert them into large windows. The author of the photograph, Félix Mena (Burgos, 1861 - Pamplona, 1935), settled in the Navarrese capital around 1884 and soon became a partner with José Roldán between 1888 and 1899. Later, when he became independent, he worked in Pamplona and Elizondo. In trying to establish the chronology of the photograph of Arizcun, it was essential to check the account book of the aforementioned town at enquiry and to verify that between 1923 and 1924 the church was painted and many other works were carried out, including the organ. Therefore, the photo is from 1924 and is of great value because it is prior to the reforms carried out fifty years later, which were very unfortunate from the point of view of cultural heritage.