Feast of the infants in Pamplona Cathedral on the day of the Holy Innocents

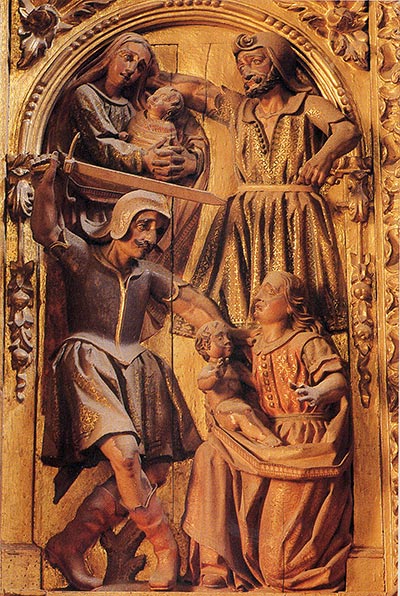

FotoCedida/Painting of conference room the Slaughter of the Innocents in the chapterhouse of Pamplona Cathedral, second half of the 16th century.

In the past, cathedrals, collegiate churches and some particularly important parishes had their own schools of choirboys or choirboys, in order to solemnise the liturgy with the singing of the white voices. In Pamplona Cathedral they are documented in detail from the 16th century onwards.

Children's voices chosen from different villages sang for a short period of years in the cathedral choir. Their names are known from various documents. The chapel master was responsible for training for these children and for teaching them music and some instruments. As there was a great deal of work to be done, solutions were often found within the chapels so that the work of care and learning could be shared with other clerics in the service of the cathedral.

The infantes of the cathedral formed a collegiate body until the 19th century, similar to other Spanish cities. The issue of four that existed in the 16th century was increased to twelve by Bishop Antonio Zapata, at the same time as he reorganised the chapel and provided it with new income. Some of the teachers made an effort and even protected the infants. We cannot fail to mention the attitude of Urbán de Vargas, chapel master who, in 1640, opposed the transfer of the infante Miguel Jordán to Madrid, at the request of the Count of Castrillo, suspecting that there he would become part of the castrados or "caponcillos".

Leocadio Hernández Ascunce (1883-1965), chapel master of Pamplona Cathedral from 1939 until his retirement in 1953, was choir infante between 1892 and 1900. With his knowledge of the institution within the walls, he reminds us that the choirboys lived together and in their little chapel they celebrated their own functions and novenarios, for which purpose they composed their own way and with their own knowledge, gozos, songs and motets. Goñi Gaztambide has dealt with how they lived, studied, amused themselves and sang on a daily basis, their musical, academic and moral training in the 17th century in a documented study, while for the 18th century, María Gembero provides us with abundant information data , in her magnificent work on music in the cathedral in the 18th century.

The bishopric in Spanish cathedrals

In most Spanish cathedrals, the feast of the bishop was celebrated by electing one of the infants to exercise jurisdiction on April Fool's Day. The biographer of Fray Hernando de Talavera, the first archbishop of Granada, gives us an account of this custom when he states that in all the cathedrals of the 16th century a bishop was elected on the day of Saint Nicholas, "whose dignity lasted until the day of Innocents: in which the offices of the elders were exchanged for those of the minors, with the latter commanding and the former obeying....On April Fool's Day, the bishop was taken from his high school to the choir, dressed as a pontifical, and accompanied by the other officials, who in their robes and surplices represented the new dean and chapter of the church, and the dignitaries and canons served as chaplains and servants of the bishop...".

In Tudela, we have news informing us that, in 1724, the suppression of masks, disguises and innocents was ordered for the altar boys, both on the eve and on the 28th itself. In the cathedral of Calahorra, the tints of the celebration at the end of the Age average were truly grotesque, judging by the following agreement adopted by the canons on 29 December 1491, probably chastened by what had happened the previous day: "they ordered that from now on the choir boys should not wear horns on April Fool's Day, nor preach, nor do they commit any other dishonesty, except that they sit on the chairs, according to the use and custom, nor should they carry horns to the dignitaries and canons". Years later, these reminiscences of the fiestas de locos seem to have been banished, as in 1587 the only thing that the chapter prohibited was that the choirboys "should make a bishopric and be given half a ram and 16 reales, as usual, and that they should strike outside the church so as not to disturb it". The Calaguritan infants, as in other places, were to leave the church for this very common entertainment in medieval Europe, which gradually abandoned the sacred space from the 16th century onwards.

Far from these examples of Tudela and Calahorra, we must remember that in Seville, Archbishop Deza reformed the feast in his cathedral, because the dome of the cathedral had collapsed on April Fool's Day, and there were those who believed that it was divine punishment for the profanations that took place in the temple by the bishop and his court.

Relief of the Slaughter of the Innocents on the altarpiece of Santa Catalina in Pamplona Cathedral, 1686.

The fiesta in Pamplona Cathedral

In the Pamplona church, the feast of the Innocents was, par excellence, the day of that small community of children, in which they played a very special role. From two unpublished documents that we have located in the chapterhouse file , we can get an idea of how the most serious aspect of the feast took place: the liturgy. The representation of the slaughter of the children could be seen both in the relief of the altarpiece of Santa Catalina, a work produced in 1686, and in the eighteenth-century painting of the chapterhouse conference room .

The first document from Pamplona to which we refer is a memorial from the master of ceremonies, Don Bernardo Astráin, addressed to the chapter on Christmas Eve 1825. As a connoisseur of ecclesiastical legislation and rubrics, Don Bernardo wrote several works and was sample in his report inflexible with certain customs.

In the first paragraph of his report we read: "The master of ceremonies feels obliged to inform Your Majesty that certain acts that are performed on April Fool's Day are in his opinion irregular and ridiculous. that certain acts that are performed on April Fool's Day are, in his opinion, irregular and ridiculous: namely, dressing the infants in chaplains' costumes, occupying the first seats in the lower choir and performing other ministries that do not correspond to them; the appointment of chaplains to carry the candlesticks, say the verses of the hours and take the sergeant's clothes, and that the Epistle and the Gospel are sung by those who do not do so ordinarily. Songs have also been sung, at times, somewhat profane, and in different languages and farcical style. And on the organ, both on this day and on Christmas Day, they have taken the liberty of playing purely theatrical sonatas and the same ones that are used in the dances".

He immediately goes on to quote numerous authors, texts full of erudition and legislation from the Congregation of Rites. At the end, aware of the harshness of the writing, the aforementioned master of ceremonies feels obliged to state that it was not his "intention to censure the infants on this day to perform the function, provided that it is in an edifying manner and that all ridicule is banished". The chapter agreed that the infantes should wear their own costume on this day, and that the candlesticks should be carried by young boys who had been selected for this purpose.

The text speaks for itself and is so clear in its content and intentions that it leaves little room for comment. We would just like to point out that the whole atmosphere was experienced by the most outstanding choirboy of all time in the Pamplona cathedral, Don Hilarión Eslava himself, who was in the cathedral as a choirboy between 1817 and 1823 and from the latter year until 1828 as an instrumentalist and with other duties in the music chapel. Undoubtedly, the great musician knew all the protagonists of that denunciation, from his companions to the stern master of ceremonies. It is a pity that we do not have a testimony from Eslava to illustrate from his point of view the whole of that passage of the high school of infants. We do not possess a testimony, such as the one that Don Hilarion recalls of the famous Miguel de Arrózpide, known as the "President", who clung to his shawm and protested against the introduction of violins into the music chapel. These allusions to Arrózpide are difficult to elucidate, as he himself was a violinist and the preference for the shawm is interpreted by María Gembero in the case of the accompaniment used in the processions of the Diputación del Reino, when he attended religious functions.

Despite the severity of the master of ceremonies' report , the infants continued to play a leading role in later years and even decades. A text, in the form of a chronicle of some cathedral events, which covers the festive calendar from St. Martin's Day 1829 and the following year, possibly the work of Astráin himself, informs us that on 27 December, the third day of Christmas Easter, the choirboys were already taking centre stage. The text reads: "A Prima canta un infante la calenda. At Vespers they all sing the Antiphon of Innocents and from Compline, as well as at the station they sing the sochantres. Day 28. From Prima in which one of them also sings the calenda and they sing the whole official document and the infants sing the mass. One of them played the organ at first Vespers and at mass, the violins two, and the others sang it with mass. At second vespers they intoned and their feast was over".

Infants in the organ case of the parish church of San Pedro de Puente la Reina, 18th century.

The decline of the festival with the secularisation of the chapter

The second text we were referring to is found in a compilation of cathedral customs and practices from the end of the 19th century. In dealing with the feast of the Innocents and after narrating the sacred offices, canonical hours, mass, procession ...etc., the compiler makes some important observations for our purpose.

The most substantial information that he gives us about the leading role played by choirboys on the feast of the Innocents lies in an observation that reads: "On this feast of the Holy Innocents, the choir used to be led by the children, according to internship of this church. They sang the antiphons, intoned the psalms... and the chaplains and psalmists sang the verses, that is, they did what the infants did. They also sang the mass, the major conducting the orchestra and they sang carols after the Sanctus until the Communio, and for this purpose they stopped singing the Pater Noster and the Pax Domini, which by the way was quite improper. The infants also incensed and brought the peace to the choir instead of the sacristans. This old internship ceased around the year 1870, no doubt due to a shortage of infants and because they were no longer collegiate and for other reasons".

From these brief but substantial lines, we deduce that some of the secular practices of the choir of infants ended up in the hands of more rigorist canons, in tune with the Cecilianism that triumphed in Europe in those years. Among them we must mention the aforementioned don Pedro María Ilundáin who, as canon and archdeacon, addressed the chapter on several occasions to put an end to certain liturgical and musical anomalies, and canon don Mercader who, in 1866, wrote a report on music in which he echoes Cecilianism and some ideas of don Hilarión Eslava in his writings on sacred music, particularly in 1860 when concluding the Lira Sacro-Hispana (Sacred-Hispanic Lyre). In this regard, it should be remembered that López Calo has considered don Hilarión as the first Spanish musician who proposed a plan for the improvement of religious music at a national level, creating a doctrinal corpus to that effect, as well as the only one who, until the Motu Proprio of St. Pius X a great reform.

Canon Mercader's report envisaged the suspension of music from the music stand in most of the functions, unless the chapel could perform it properly. It also proposed the prohibition of the piano "except in the full orchestra, when it serves as a base and direction for the orchestra, in cases where the tuning of the organ does not correspond" and the figle, "as long as it does not accompany at least twenty other instruments", warning that the latter instrument could be replaced by the bassoon or the euphonium. After arguing their positions, the memorial deals with the ownership of the cathedral's music, its custody and performance.

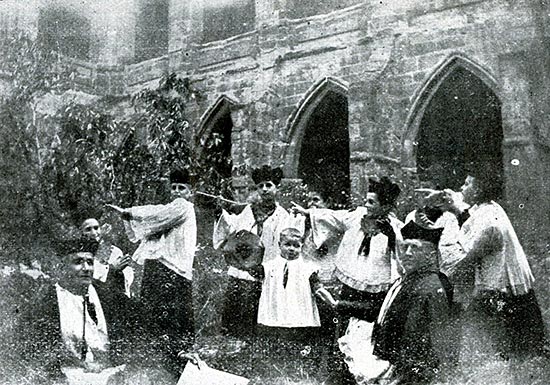

Infantes de Fitero in the cloister of the abbey, 1904. Photograph by Mauro Azcona. Private collection

To find out more

FERNÁNDEZ GRACIA, R., Navidad en la catedral de Pamplona. Rites, festivity and art, Pamplona, department de Historia del Arte. University of Navarre, 2007

GEMBERO USTÁRROZ, M., La música en la catedral de Pamplona, Pamplona, Government of Navarre, 1995.

GOÑI GAZTAMBIDE, J., La capilla musical de la catedral de Pamplona. Desde sus orígenes hasta 1600, Pamplona, Capilla de Música, 1983 and La capilla musical de la catedral de Pamplona en el siglo XVII, Pamplona, Capilla de Música, 1986.