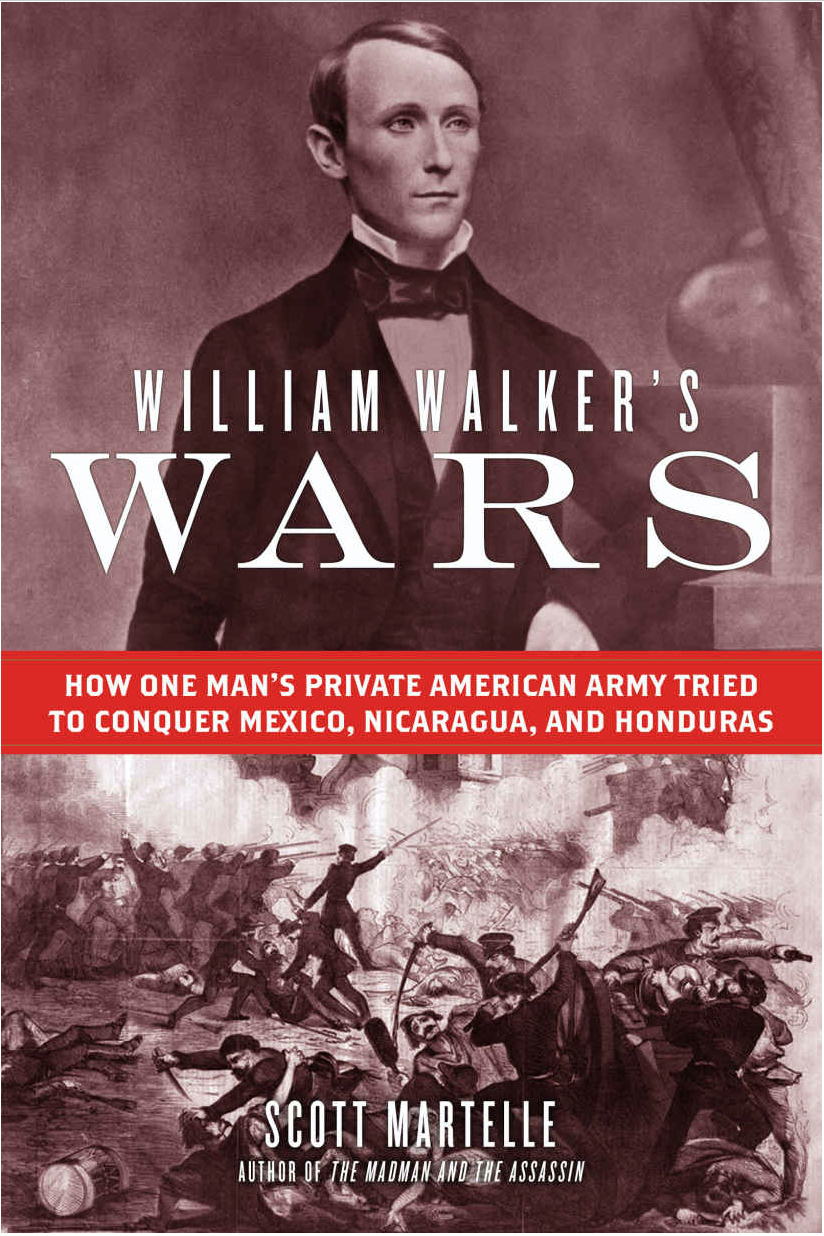

[Scott Martelle, William Walker's Wars. How One Man's Private Army Tried to Conquer Mexico, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Chicago Review Press. Chicago, 2019. 312 p.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

The history of U.S. interference in Latin America is long. In plenary session of the Executive Council Manifest Destiny of westward expansion in the mid-nineteenth century, to extend the country from coast to coast, there were also attempts to extend sovereignty to the South. Those who occupied the White House were satisfied with half of Mexico, which completed a comfortable access to the Pacific, but there were personal initiatives to attempt to purchase and even conquer Central American territories.

The history of U.S. interference in Latin America is long. In plenary session of the Executive Council Manifest Destiny of westward expansion in the mid-nineteenth century, to extend the country from coast to coast, there were also attempts to extend sovereignty to the South. Those who occupied the White House were satisfied with half of Mexico, which completed a comfortable access to the Pacific, but there were personal initiatives to attempt to purchase and even conquer Central American territories.

One of those initiatives was led by William Walker, who at the head of several hundred filibusters -the American Falange-, snatched the presidency of Nicaragua and dreamed of a slave empire that would attract the investments of American Southerners if slavery was abolished in the United States. Walker, from Tennessee, first tried to create a republic in Sonora, to integrate that Mexican territory into the United States, and then focused his interest on Nicaragua, which was then an attractive passage for Americans who wanted to cross the Central American isthmus to the gold mines of California, where he himself had sought his fortune. Disallowed and detained several times by the US authorities, due to the problems he caused them with the neighboring governments, he was finally expelled from Nicaragua by force of arms and shot to death when he tried to return by setting foot in Honduras.

Scott Martelle's book is both a portrait of the character - someone without special leadership skills and with a rather delicate appearance unbecoming of a mercenary chief, who nevertheless knew how to generate lucrative expectations among those who followed him (2,518 Americans came to enlist) - and a chronicle of his military campaigns in the South of the United States. It also describes well the mid-19th century atmosphere in cities like San Francisco and New Orleans, full of migrants coming from other parts of the country and in transit to wherever fortune would take them.

It also offers a detailed account of the business developed by the magnate Vanderbilt to establish a route, inaugurated in 1851, that used the San Juan River to reach Lake Nicaragua and from there out to the Pacific, with the aim of establishing a railroad connection and the subsequent purpose to build a canal in a few years. Although the overland route was longer than the one that at that time was also being traced under similar conditions on the Isthmus of Panama, the boat trip from the United States to Nicaragua was shorter than the one that required reaching Panama. The latter explains why during the second half of the 19th century the project Nicaragua Canal had more followers in Washington than the Panama Canal.

Although Panama is one of the symbols of US interference in its "backyard", the success of the transoceanic canal project and its return to the Panamanians largely deactivates a "black legend" that still exists in the Nicaraguan case. Nicaragua is probably the Central American country that has experienced the most US "imperialism". The Walker episode (1855-1857) marks a beginning; then followed the US government's own military interventions (1912-1933), Washington's close support for the Somoza dictatorship (1937-1979) and direct involvement in the fight against the Sandinista Revolution (1981-1990).

Walker arrived in Nicaragua attracted by the U.S. interest in the inter-oceanic passage and with the excuse of helping one of the sides facing each other in one of the many civil wars between conservatives and liberals that were taking place in the former Spanish colonies. Elevated to chief of the Army, in 1856 he was elected president of a country in which he could barely control the area whose center was the city of Granada, on the northern shore of Lake Nicaragua.

As he established his power, he moved away from any initial idea of integrating Nicaragua into the United States and dreamed of forging a Central American empire that would even include Mexico and Cuba. Slavery, which in Nicaragua had been abolished in 1838 and he reinstated in 1856, entered into his strategy. He imagined it as a means of preventing Washington from renouncing to extend its sovereignty to those territories, given the internal balances in the US between slave and non-slave states, and as a capital attraction for southern slaveholders. He was finally expelled from the country in 1857 thanks to the push of an army assembled by neighboring countries. In 1860 he attempted a return, but was captured and shot in Trujillo (Honduras). His adventure was fueled by the belief in the superiority of the white and Anglo-Saxon man, which led him to despise the aspirations of the Hispanic peoples and to overestimate the warlike capacity of his mercenaries.

Martelle's book responds more to a historicist purpose than a divulgative one, so its reading is not so much for the general public as for those specifically interested in William Walker's fulibusterism: an episode, in any case, of convenient knowledge on the Central American past and the relationship of the United States with the rest of the Western Hemisphere.