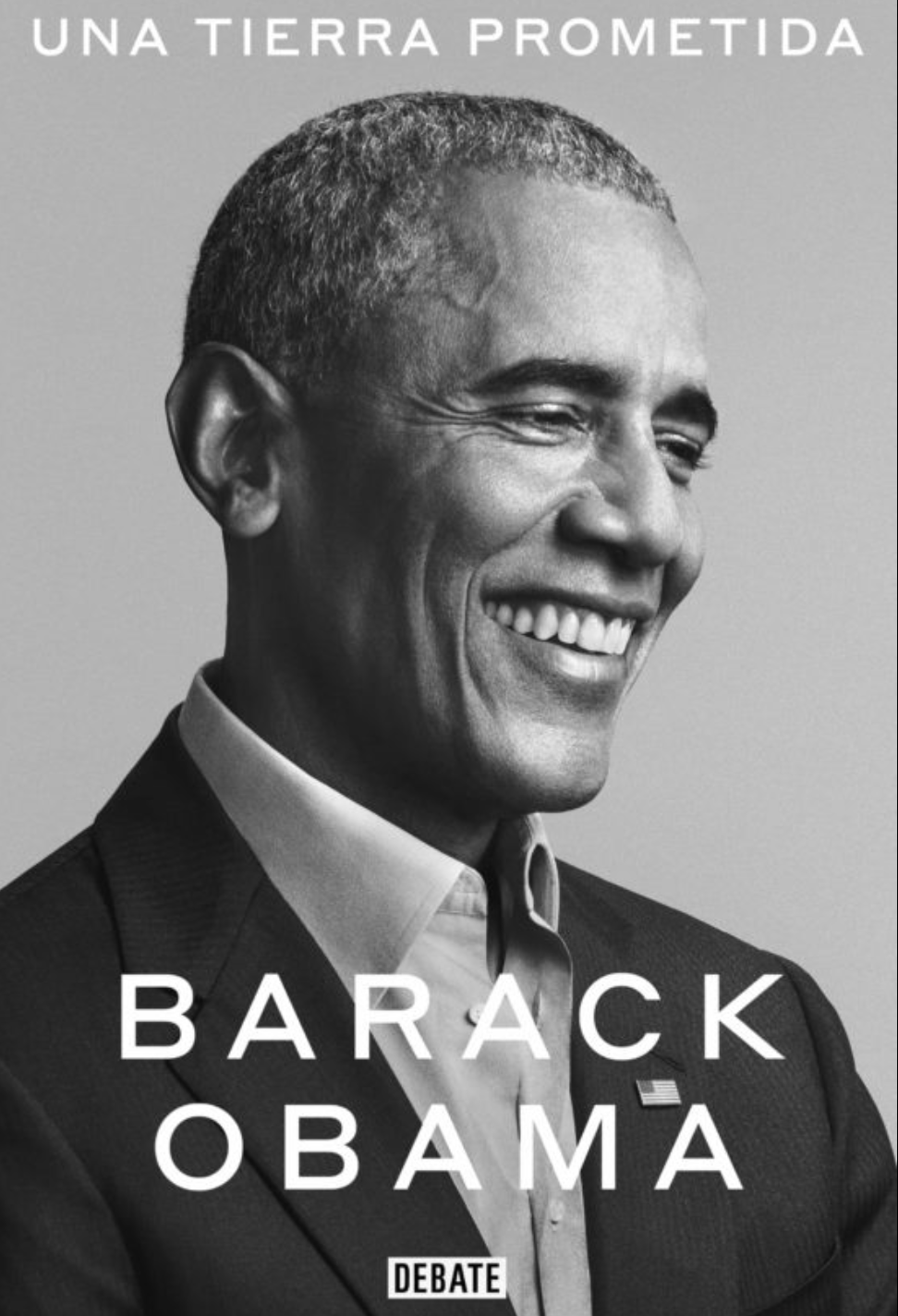

[Barack Obama, A Promised Landdiscussion: Madrid, 2020), 928 pp.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

A president's memoirs are always an attempt to justify his political actions. Having employee George W. Bush less than five hundred pages in "Decision Points" to try to explain the reasons for a more controversial management in principle, that Barack Obama uses almost a thousand pages for the first part of his memoirs (A promised land only covers the third year of his eight-year presidency) seems an excess: in fact, no U.S. president has ever required so much space in this exercise of wanting to tie up his bequest.

A president's memoirs are always an attempt to justify his political actions. Having employee George W. Bush less than five hundred pages in "Decision Points" to try to explain the reasons for a more controversial management in principle, that Barack Obama uses almost a thousand pages for the first part of his memoirs (A promised land only covers the third year of his eight-year presidency) seems an excess: in fact, no U.S. president has ever required so much space in this exercise of wanting to tie up his bequest.

It is true that Obama has a taste for the pen, with some previous books in which he has already shown good narrative skills, and it is possible that this literary inclination has defeated him. But probably more decisive has been Obama's vision of himself and his presidency: the conviction of having a mission statement, as the first African-American president, and his ambition of wanting to bend the arc of history. When, with the passage of time, Obama begins to be just one more in the list of presidents, his book vindicates the historical character of his person and his achievements.

The first third of A Promised Land is particularly interesting. There is a cursory review of his life prior to entrance politics and then the detail of his degree program leading up to the White House. This part has the same inspirational charge that made so attractive My Father's Dreams, the book that Obama published in 1995 when he launched his campaign for the Illinois State Senate (in Spain it appeared in 2008, as a result of his campaign for the presidency). We can all draw very useful lessons for our own staff improvement: the idea of being masters of our destiny, of becoming aware of our deepest identity, and the security that this gives us to carry out many enterprises of great value and transcendence; to put all our efforts into a goal and take advantage of opportunities that may not come again; in final, to always think out of the box (when Obama saw that his work as senator of Illinois had little impact, his decision was not to leave politics, but to jump to the national level: He ran for senator in Washington and from there, only four years later, he reached the White House). These pages are also rich in lessons on political communication and electoral campaigns.

But when the narrative begins to address the presidential term, which began in January 2009, that inspirational tone falters. What was once a succession of generally positive adjectives for everyone begins to include diatribes against his Republican opponents. And here is the point that Obama does not manage to overcome: giving himself all the moral merit and denying it to those who, with their votes in congress , disagreed with the legislation promoted by the new president. It is true that Obama had a very frontal civil service examination from the Republican leaders in the Senate and the House of Representatives, but they also supported some of his initiatives, as Obama himself acknowledges. For the rest, which came first, the chicken or the egg? Large sectors of the Republicans immediately jumped on the bandwagon, as soon evidenced by the Tea Party tide in the 2010 mid-term elections (in a movement that would eventually lead to support for Trump), but it is also because Obama had arrived with the most left-wing positions in American politics in living memory. With his idealistic drive, Obama had set little example of bipartisan effort in his time in the Illinois and Washington Senate; when some of his reforms from the White House were blocked in congress, instead of seeking an accommodation -accepting a politics of the possible- he went to the streets to confront citizens with politicians who opposed his transformations, further entrenching the trenches of one and the other.

The British historian Niall Ferguson has pointed out that the Trump phenomenon would not be understood without Obama's previous presidency, although the bitter political division in the United States is probably a matter of a deep current in which leaders play a less leading role than we would suppose. Obama saw himself as the ideal person, because of his cultural mix (black, but raised by his white mother and grandparents), to bridge the widening rift in American society; however, he was unable to build the necessary ideological bridges. Bill Clinton faced a similar Republican blockade, in the congress led by Newt Gingrich, and made useful compromises: he reduced the ideological burden and brought an economic prosperity that relaxed public life.

A Promised Land includes many of Obama's reflections. He generally provides the necessary context to understand the issues well, for example in the gestation of the 2008 financial crisis. In foreign policy he details the state of relations with the major powers: animosity towards Putin and suspicion towards China, among other issues. There are aspects with different possible ways forward in which Obama leaves no room for a legitimate alternative position: thus, in a particularly emblematic topic , he charges against Netanyahu without admitting any mistake of his own in his approach to the Israeli-Palestinian problem. This is something that other reviews of the book have pointed out: the absence of self-criticism (beyond admitting sins of omission in not having been as bold as he would have wished), and the failure to admit that in some respects perhaps the opponent could have been right.

The narrative runs with a good internal rhythm, despite the many pages. The volume ends in 2011, at a random moment determined by the extension foreseen for a second submission; however, it has a climax with sufficient force: the operation against Osama bin Laden, for the first time told in the first person by the person who had the highest level of command. Although the Degree involvement of other hands in the essay is unknown, the work has a point of lyricism that connects directly with Los sueños de mi padre and that financial aid to attribute it, at least to a great extent, to the former president himself.

The book contains many episodes of the Obamas' domestic life. Obama's constant compliments to his wife, his admiration for his mother-in-law and the continuous references to his devotion to his two daughters could be considered unnecessary, especially because of their recurrence, in a political book. Nevertheless, they give the story the staff tone that Obama has wanted to adopt, giving human warmth to someone who was often accused of having a public image of a cold, distant and overly reflective person.