Breadcrumb

Blogs

![Joe Biden and Barack Obama in February 2009, one month after arriving at the White House [Pete Souza]. Joe Biden and Barack Obama in February 2009, one month after arriving at the White House [Pete Souza].](/documents/16800098/0/biden-obama-blog.jpg/ad49fcda-889d-4b84-14cc-87cf326fc61c?t=1621883654693&imagePreview=1)

▲ Joe Biden and Barack Obama in February 2009, one month after arriving at the White House [Pete Souza].

COMMENTARY / Emili J. Blasco

This article was previously published, somewhat abbreviated, in the newspaper 'Expansión'.

One of the great mistakes revealed by the U.S. presidential elections is to have underestimated the figure of Donald Trump, believing him to be a mere anecdote, and to have disregarded, as whimsical, a large part of his policies. In reality, the Trump phenomenon is a manifestation, if not a consequence, of the current American moment and some of his major decisions, especially in the international arena, have more to do with national imperatives than with fickle occurrences. The latter suggests that there are aspects of foreign policy, manners aside, in which Joe Biden as president may be closer to Trump than to Barack Obama, simply because the world of 2021 is already somewhat different from that of the first half of the previous decade.

First, Biden will have to confront Beijing. Obama began to do so, but the more assertive character of Xi Jinping's China has been accelerating in recent years. In the superpower struggle, especially for dominance in the new technological era, the United States has everything at stake vis-à-vis China. It is true that Biden has referred to the Chinese not as enemies but as competitors, but the trade war was already started by the Administration of which he was Vice-President and now the objective rivalry is greater.

Nor is the withdrawal of the United States the result of Trump's madness. Basically, it has to do, to simplify somewhat, with the energy independence achieved by the Americans: they no longer need oil from the Middle East and they no longer have to be in all the oceans to ensure the free navigation of tankers. The 'America First' was somehow already started by Obama and Biden will not go in the opposite direction. So, for example, no major involvement in European Union affairs and no firm negotiations for a free trade agreement between the two Atlantic markets can be expected.

In the two main achievements of the Obama era - the nuclear agreement with Iran sealed by the United States, the EU and Russia, and the reestablishment of diplomatic relations between Washington and Havana - Biden will find it difficult to follow the path then defined. There may be attempts at a new rapprochement with Tehran, but there would be greater coordination against it on the part of Israel and the Sunni world, instances that now converge more. Biden may find that less pressure on the ayatollahs pushes Saudi Arabia toward the atomic bomb.

As for Cuba, the return to dissent will be more in the hands of the Cuban government than in those of Biden himself, who in the electoral loss in Florida has been able to read a rejection of any condescension with Castroism. Some of the new restrictions imposed by Trump on Cuba may be dismantled, but if Havana continues to show no real willingness to change and open up, the White House will no longer have to continue betting on political concessions to credit .

In the case of Venezuela, Biden will probably withdraw a good part of the sanctions, but there is no longer room for a policy of inaction like that of Obama. That Administration did not confront Chavismo for two reasons: because it did not want to bother Cuba given the secret negotiations it was holding with that country to reopen its embassies and because the level of lethality of the regime had not yet become unbearable. Today, international reports on human rights are unanimous on the repression and torture of the Maduro government, and also the arrival of millions of Venezuelan refugees in the different countries of the region make it necessary to take action on the matter. Here it is to be hoped that Biden can act in a less unilateral manner and, without ceasing to exert pressure, seek coordination with the European Union.

It often happens that whoever arrives at the White House takes care of national affairs in his first years and later, especially in a second term, focuses on leaving an international bequest . Because of age and health, it is possible that the new tenant will only be in office for a four-year term. Without Obama's idealism of wanting to "bend the arc of history" - Biden is a pragmatist, a product of the American political establishment - nor businessman Trump's rush for immediate gain, it is hard to imagine that his Administration will take serious risks on the international scene.

Biden has confirmed his commitment to begin his presidency in January by reversing some of Trump's decisions, notably on climate change and the Paris agreement ; on some tariff fronts, such as the outgoing administration's unnecessary punishment of European countries; and on various immigration issues, especially concerning Central America.

In any case, even if the Democratic left wants to push Biden towards certain margins, believing that they have an ally in Vice-President Kamala Harris, the president-elect can make use of his moderation staff : the fact that he has obtained better result in the elections than the party itself gives him, for the time being, sufficient internal authority. For the rest, the Republicans have held up quite well in the Senate and the House of Representatives, so that Biden arrives at the White House with less support on Capitol Hill than his predecessors. That, in any case, may help to reinforce one of the traits most valued today in the Delaware politician: predictability, something that the economies and foreign ministries of many of the world's countries are anxiously awaiting.

EPP, the Paraguayan guerrilla group that grew out of political carelessness

Emerged in 2008, the Paraguayan People's Army has created a conflict that has already claimed a hundred dead.

Emerged in 2008, the Paraguayan People's Army has created a conflict that has already claimed a hundred dead.

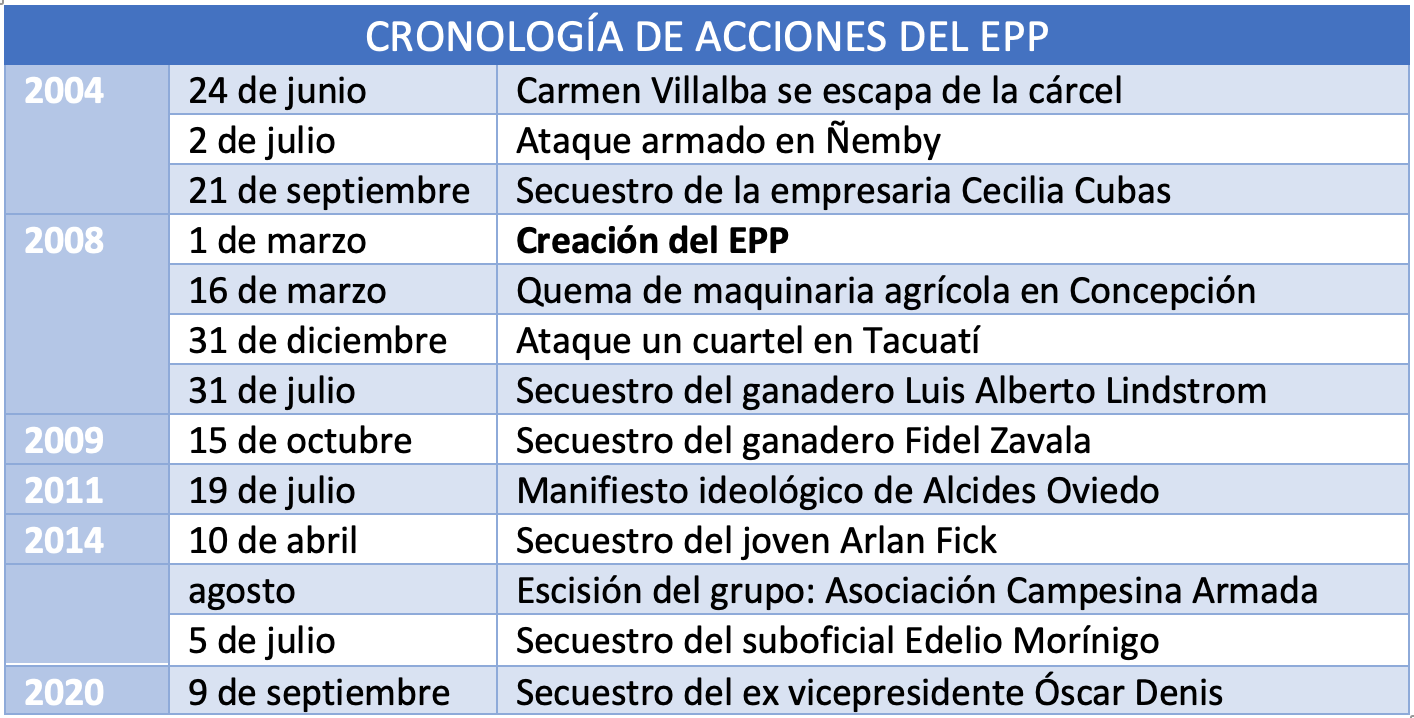

Marxist guerrillas in Latin America are a thing of the past. That conviction led to underestimate the emergence in 2008 of the Paraguayan People's Army (EPP), which since then has carried out a hundred violent actions, especially in rural areas of the northeast of the country. The conflict has claimed a hundred dead and as many wounded; there have also been kidnappings of personalities, which have given the EPP special media coverage. The creation of a controversial special military-police corps has not achieved the goal of putting an end to the group, which has led to criticism of the government's management of the problem.

article / Eduardo Villa Corta

The Paraguayan People's Army (EPP) was considered since its emergence as a small group of radicals that would have little to do. However, in just ten years it has become an organization capable of confronting the Paraguayan State: it has carried out a hundred terrorist actions, including a dozen kidnappings, causing some sixty deaths and a hundred wounded.

![EPP influence zones (light red) and places where there have been group instructions (dark red) [Mikelelgediento].](/documents/portlet_file_entry/16800098/epp-paraguay-mapa.png/604d99a8-454a-4a1c-3e01-b6bd6a1a799c?imagePreview=1)

EPP influence zones (light red) and places where there have been group instructions (dark red) [Mikelelgediento].

With an issue of activists ranging from thirty of its hard core to two hundred if its support networks are considered, the EPP has been a problem for the government for several years, which has not been able to dismantle it: 30 militants have died in confrontations with the forces of law and order and a hundred have been arrested, but the image offered by the authorities is one of ineffectiveness. The Paraguayan government's negative credit is also the fact that it did not take seriously the threat posed by the group 's constitution and its first actions.

The EPP was officially formed on March 1, 2008. Although its founders and main leaders had already planned the creation of this group prior to this date, its roots go back to 1992 and the Patria Libre Party, as documented by researcher Jeremy McDermott. The EPP presents itself as an armed group against the "bourgeois liberal" parliamentary system, but above all it is a Marxist movement that promotes the uprising of Paraguay's peasantry, hence its attempt to take root in the rural northeast of the country.

The 2008 presidential victory of Fernando Lugo at the head of a leftist alliance, putting an end to six decades of political dominance by the Colorado Party, may have encouraged the formation of the EPP, which then believed it was justified in its actions with the removal of Lugo in 2012 through a controversial impeachment trial carried out by the Parliament and labeled by Lugo's supporters as a coup d'état.

The first EPP attack, on March 16, 2008, consisted of the burning of agricultural machinery in the department of Concepción. The next was in December of the same year, with an attack on a barracks in Tacuatí, in the department of San Pedro. Since then, their movements have been centered especially between the south of the first of these Departments and the north of the second.

Despite being a more or less delimited zone, dismantling the EPP is not easy because the EPP's modus operandi makes its movements unpredictable. This is because, as McDermott explains, the group does not act like other insurgent organizations, such as the FARC. The core of the EPP is made up of some 30 full-time fighters, most of whom have family ties. They are led by ringleaders Alcides Oviedo and his wife Carmen Villalba, who are in jail; one of the leaders on the ground is Oswaldo Villalba. In addition, there are about fifty part-time activists, a logistical network that could reach two hundred people and local sympathizers who, without being very involved in the cause, provide information on search operations of the security forces. The group suffered in 2014 the split of one of its columns, which was renamed the Armed Peasant association (ACA) and in 2018, in agreement with the authorities, the EPP split into two groups to face the pressure of the security forces.

The aforementioned figures speak of a small group , far from the 8,000 members that the FARC had in 2016 at the time of their demobilization or the 4,000 members that the ELN currently has in Colombia, or the 3,000 that were attributed to Chile's Manuel Rodriguez Patriotic Front. Although the EPP is more similar to the latter, its operational cessation in 1999 left the FARC as the main training group for those who would later create the EPP, as evidenced by the documentation found in the computer of FARC leader Raul Reyes and the kidnapping of businesswoman Cecilia Cubas, daughter of a former Paraguayan president, at the end of 2004.

This action marked what has been a line of action for the EPP. Since 2008, in addition to extortion and assaults in order to finance itself, the group has carried out kidnappings in order to achieve greater media impact. These have been carried out against relatives of former presidents of the country or personalities with a high political profile , for whose release ransoms in excess of five million dollars have been order , although lower figures have been agreed in negotiations. It is usually agreed to submit part of the money in cash and part in food for the towns surrounding the EPP's area of operations.

The group has also carried out extortions and assaults in those areas where it operates, demanding "revolutionary taxes" from landowners and cattle ranchers, from whom they also steal cattle and food to meet the organization's daily sustenance needs.

Other notable actions carried out by the EPP are bombings. For example, there was an attack against the Supreme Court of Justice in Asunción at the beginning of the group's operations. A more recent attack was perpetrated on August 27, 2016 against a military vehicle in the eastern zone of Concepción: the explosives exploded as the convoy passed by and then the terrorists liquidated the survivors with firearms; eight military personnel were killed in the attack. According to authorities, this event marked a leap in the EPP's operations, from a group seeking economic resources to an organization with greater operational and military capacity.

To confront the EPP, President Horacio Cartes created the Joint Task Force (FTC) in 2013 in response to evidence that police action was ineffective, in part due to possible internal corruption. The JTF is composed of members of the Armed Forces, the National Police and the National Anti-Drug administrative office , under the command of a military officer and reporting directly to the president. The more expeditious nature of this unit has generated some controversy in the social and political discussion .

The EPP's most recent operation was the kidnapping of former Paraguayan vice-president Óscar Denis on September 9, 2020. For the release of Denis, leader of the Authentic Radical Liberal Party and active participant in Lugo's impeachment, the terrorists demand the release of their leaders, Alcides Oviedo and Carmen Villalba, as well as the submission of food supplies for the rural areas where they operate. The deadline set by the organization expired a few days later without the Government attending their request. There have been citizen mobilizations demanding Denis' freedom and the status is being followed in the country with concern, putting President Mario Abdo Benítez in a tight spot.

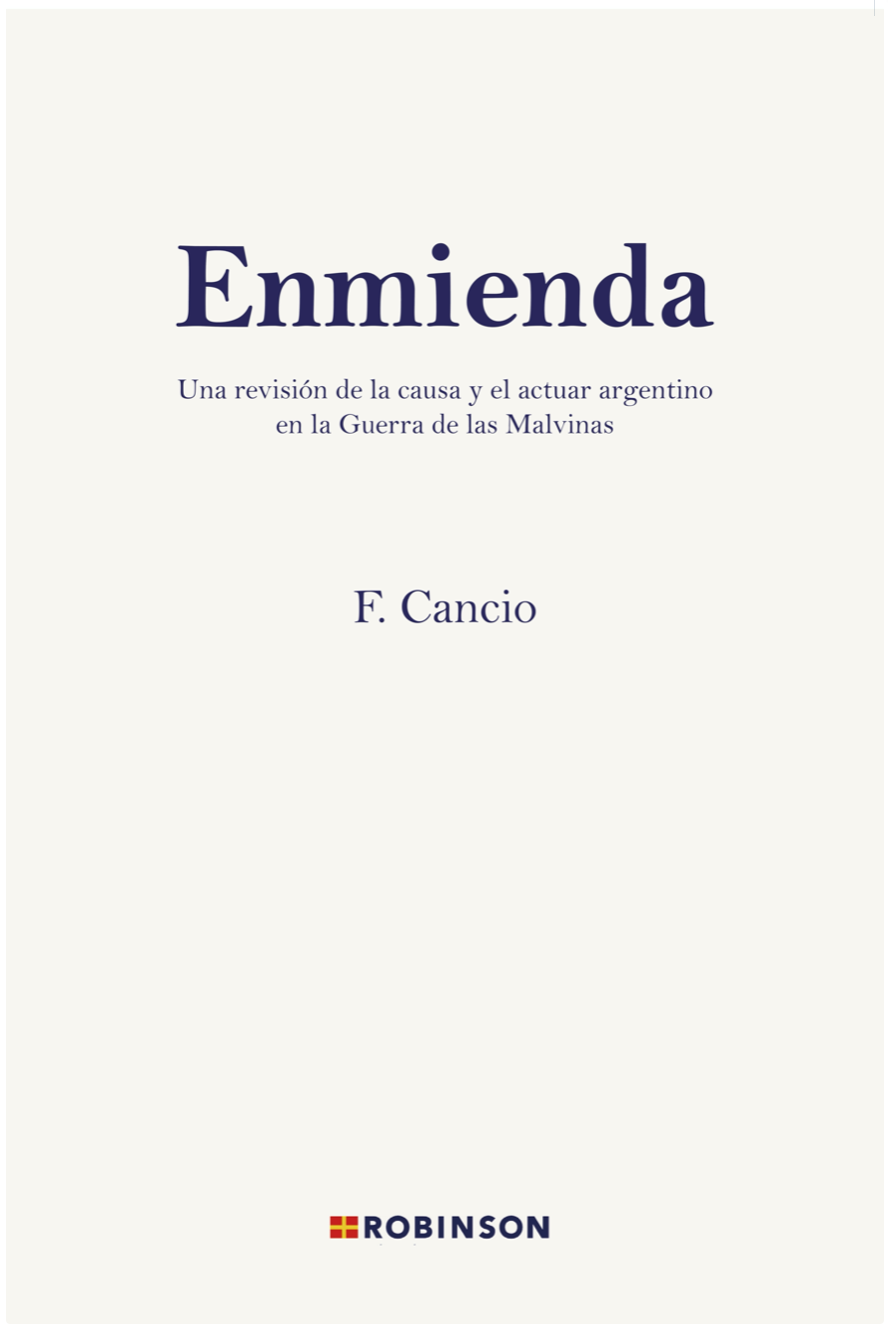

[Francisco Cancio, Enmienda: una revisión de la causa y el actuar argentino en la Guerra de las Malvinas (Náutica Robinsón: Madrid, 2020), 406 pp.]

review / Ignacio Cristóbal

This is an excellent book that analyzes some controversial issues of the Malvinas War (1982). The author, Francisco Cancio, is an expert on the subject and has made a conscientious search for information over the years in his visits to Argentina and the United Kingdom.

This is an excellent book that analyzes some controversial issues of the Malvinas War (1982). The author, Francisco Cancio, is an expert on the subject and has made a conscientious search for information over the years in his visits to Argentina and the United Kingdom.

It is not a book on the history of the Malvinas War; there are other manuals that explain it very well, but here the author has tried something else. Whoever opens the book should have some knowledge of what happened then in the South Atlantic or else obtain it before going into its pages.

In my case, it was not difficult to get "hooked" by reading the book. From the data the author gives, he had similar experiences to mine. I was also watching the news in the spring of 1982 sitting next to my father, a military man; for our generation it was our first war. And like him, who on his trips to the United Kingdom, I imagine to practice his English language skills, would dive into British bookstores in search of documentation, I also learned about the Falklands when I was in those lands perfecting my English, going to museums and bookstores and to the barracks of Colchester, the city where I spent two summers, to talk to veterans of the conflict. You will be forgiven if, because of this staff involvement, I let my sympathy for the Argentine side go a little, while admiring the professionalism shown by the British troops.

The Malvinas War was a complete war from the military point of view. There were air and naval combats; intervention of submarines and satellites; landing and ground operations of special operations units, as well as actions of units at battalion level. It is very welcome that the first chapter, graduate "Genesis", while introducing the conflict begins to "prick balloons" about the real reason for going to war.

And the chapters go on and on with issues such as the "Super Etendart and the Exocet", where we imagine the Argentine naval pilots training in Brittany, France and leaving the flag very high, as it should have been. The interest increases when the author gets into the intelligence operations to "arm", without an "instruction book", the missiles that were already in Argentina. The French government played a complicated role in the conflict, but the diplomatic aspect (it was a member of NATO) took precedence over the commercial aspect. The French technicians sent to Argentina were the ones who gave the "do de pecho" by siding with Argentina and juggling to avoid creating more problems in the international balance.

The chapter on land operations is excellent and makes a spear in favor of the Argentine forces that had to deal with the enemy and the lack of logistic support from the continent. In those days there was a discussion in the public opinion about the dichotomy "conscript army" versus "professional army". It is clear in the chapter the damage that the Argentines inflicted on the reconquerors, but also their adverse status : the lack of basic means for resistance, counterattack and, why not to say it, hunger and cold.

The naval part is dealt with in two interesting chapters that tell the story of the submarine "San Luis", which was bothering the British fleet during the whole war. If there had been no war, that submarine would have stayed in port. This is the level of those brave submariners. The other chapter is about the failed meeting, due to the lack of wind, of the two fleets. It is possibly one of the most critical moments of the battle. Had there been wind, the A-4 Skyhawk of the Argentine Navy could have driven the British fleet back to its home ports.

A separate chapter is "La guerra en los cielos" (The war in the skies), which gathers some of the most courageous operations of the Argentine pilots in those days. The author puts us in the cockpits of the fighters whose images still make our hair stand on end. Without wanting to give anything away to the reader, the interview with the former head of the Argentine Air Force in those days is for me the best part of the book. We must not forget that he was a member of the military board and the data he reveals about the "Russianfinancial aid " are very interesting and unknown.

And finally the long-awaited chapter "The Attack on the Invincible", which deals with probably the most compromising war action of the entire conflict. The author scrupulously analyzes the operation of attacking one of the two British aircraft carriers, the Invincible, with a clarity that makes it evident that something happened.

"Amendment" is, therefore, a highly recommendable book for those who already have some knowledge about the Falklands War, but at the same time it can provoke curiosity in other people who, without being initiated in this conflict, can help themselves in the reading by consulting basic information available on the Internet. It was a singular conflict, in which a country in the south of the world put in check the second power of NATO, helped without limits by the first and by a neighboring country. As Admiral Woodward, commander of the British fleet, said in his memoirs: "people do not know how close Britain came to losing the war". A fine final epitaph from a military professional who surely recognized the professionalism, bravery and courage of the enemy.

* Expert in military affairs

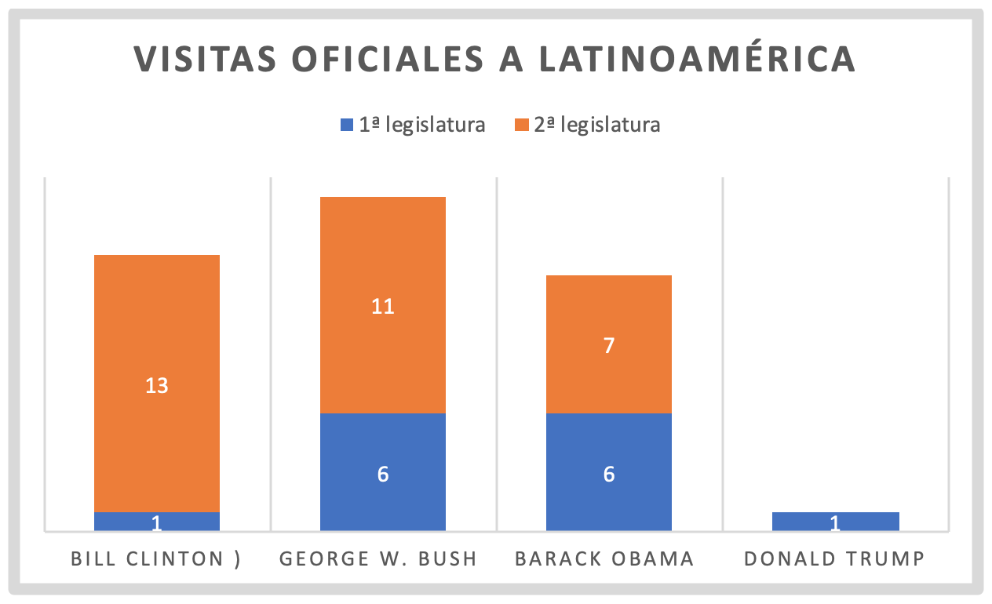

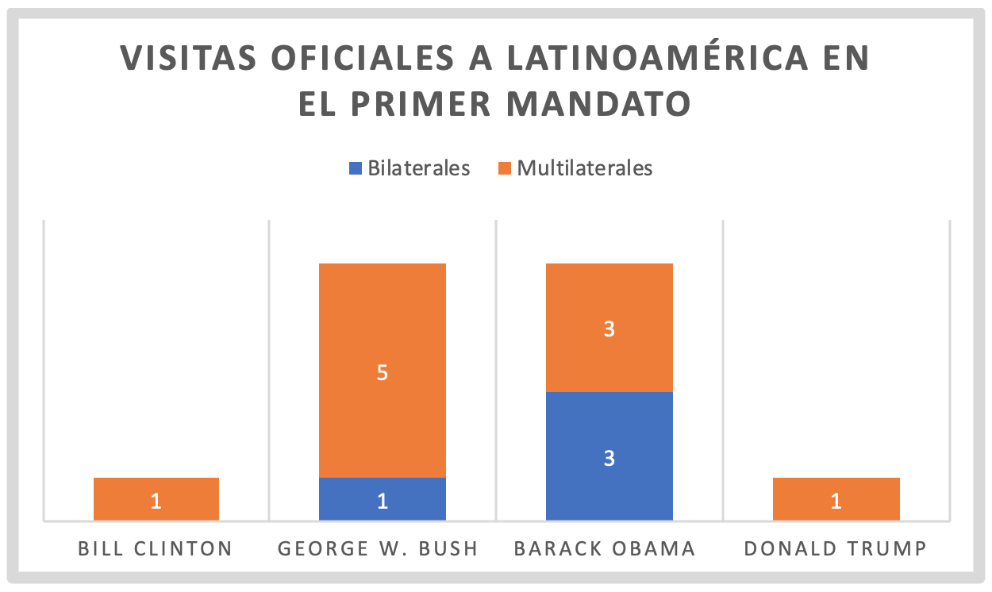

The current president made only one visit, also in the framework the G-20, compared to the six that Bush and Obama made in their first four years.

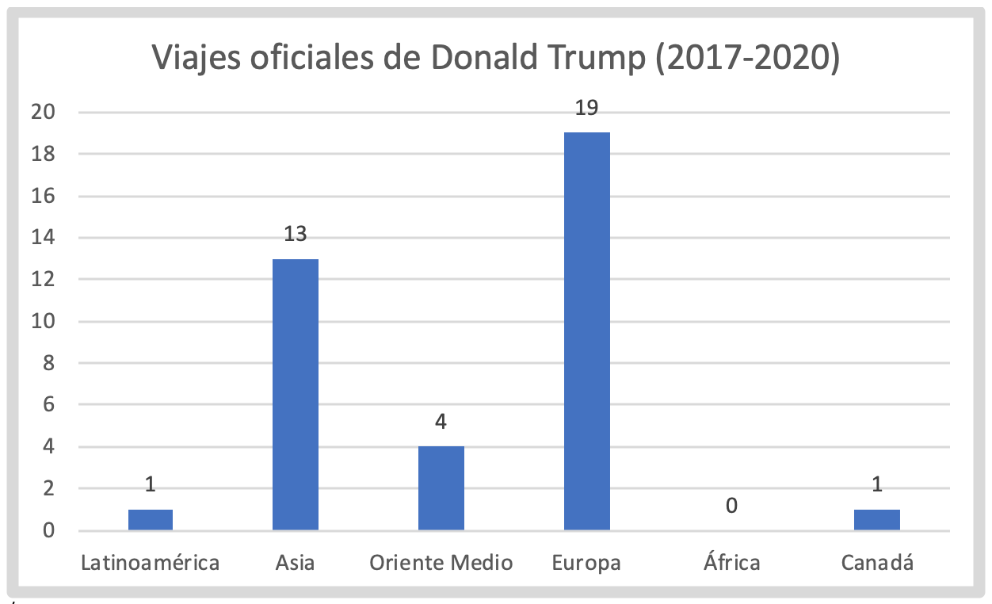

International travel does not tell the whole story about a president's foreign policy, but it does give some clues. As president, Donald Trump has only traveled once to Latin America, and then only because the G-20 summit he was attending was being held in Argentina. It is not that Trump has not dealt with the region -of course, the policy towards Venezuela has been very present in his management, but not having made the effort to travel to other countries of the continent reflects well the more unilateral character of his policy, little focused on gaining sympathy among his peers.

![signature in Mexico in 2018 of the free trade agreement between the three North American countriesdepartment Statedepartment , USA]. signature in Mexico in 2018 of the free trade agreement between the three North American countriesdepartment Statedepartment , USA].](/documents/16800098/0/viajes-trump-blog.jpg/157ee6c8-c573-2e22-6911-3ae54fe8a0a8?t=1621883760733&imagePreview=1)

▲ signature in Mexico in 2018 of the free trade agreement between the three North American countriesdepartment of State, USA].

article / Miguel García-Miguel

With only one visit to the region, the U.S. president is the one who has made the fewest official visits since Clinton's first legislature, who also visited the region only once. In contrast, Bush and Obama paid more attention to the neighboring territory, both with six visits in their first legislature. Trump focused his diplomatic campaign on Asia and Europe and reserved Latin American affairs for visits by the region's presidents to the White House or to his Mar-a-Lago resort.

In fact, the Trump Administration spent time on Latin American issues, taking positions more quickly than the Obama Administration, as the worsening Venezuelan problem required defining actions. At the same time, Trump has discussed regional issues with Latin American presidents during their visits to the United States. There has been, however, no effort at multilateralism or empathy, going out to meeting them in their home countries to discuss their problems there.

Clinton: Haiti

The Democratic president made only one visit to the region during his first term in office. After the Uphold Democracy operation to refund Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power, on March 31, 1995, Bill Clinton traveled to Haiti for the transition ceremony organized by the United Nations. The operation had consisted of a military intervention by the United States, Poland and Argentina, with UN approval, to overthrow the military board that had forcibly deposed the democratically elected Aristide. During his second term, Clinton paid more attention to regional affairs, with thirteen visits.

Bush: free trade agreements

Bush made his first presidential trip to neighboring Mexico, where he met with then-President Fox to discuss a variety of issues. Mexico paid attention to the U.S. government's attention to Mexican immigrants, but the two presidents also discussed the operation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which came into force in 1994, and joint efforts in the fight against drug trafficking. The U.S. president had the opportunity to visit Mexico three more times during his first term to attend multilateral meetings. Specifically, in March 2002, he attended the International lecture on Financing for development, organized by the United Nations and which resulted in the Monterrey Consensus; Bush also took the opportunity to meet again with the Mexican president. In October of the same year he attended the APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) summit, which that year was held in the Mexican enclave of Los Cabos. Finally, he set foot on Mexican soil once again to attend the Special Summit of the Americas held in Monterrey in 2004.

During his first term in office, Bush promoted the negotiation of new free trade agreements with several American countries, which marked his Administration's policy in relation to the Western Hemisphere. In the framework of this policy, he traveled to Peru and El Salvador on March 23 and 24, 2002. In Peru he met with the President of that country and with the Presidents of Colombia, Bolivia and Ecuador, in order to reach an agreement to renew the ATPA (Andean Trade Promotion Act), by which the US granted tariff freedom on a wide range of exports from those countries. The matter was finally resolved with the enactment in October of the same year of the ATPDEA (Andean Trade Promotion and Drug Eradication Act), which maintained tariff freedoms in compensation for the fight against drug trafficking, in an attempt to develop the region economically to create alternatives to cocaine production. Finally, in the case of El Salvador, he met with the Central American presidents to discuss the possibility of a Free Trade Agreement with the region (known in English as CAFTA) in exchange for a reinforcement of security in the areas of the fight against drug trafficking and terrorism. The treaty was ratified three years later by the U.S. congress . Bush revisited Latin America up to eleven times during his second term.

Own elaboration with data from the Office of the Historian.

Obama: two Summits of the Americas

Obama began his tour of diplomatic visits to Latin America by attendance the V Summit of the Americas, held in Port-au-Prince (Trinidad and Tobago). The Summit brought together all the leaders of the sovereign countries of the Americas except for Cuba and was aimed at coordinating efforts to recover from the recent crisis of 2008 with mentions of the importance of environmental and energy sustainability. Obama attend again in 2012 the VI Summit of the Americas held this time in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia). No representatives from Ecuador or Nicaragua attended this Summit in protest against the exclusion of Cuba to date. Neither the President of Haiti nor the Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez attended, alleging medical reasons. The summit again discussed Economics and security issues with special relevance to the war against drugs and organized crime, as well as the development of environmental policies. He also took advantage of this visit to announce, together with Juan Manuel Santos, the entrance into effect of the Free Trade Agreement between Colombia and the US, negotiated by the Bush Administration and ratified after some delay by the US congress . The Democratic president also had the opportunity to visit the region on the occasion of the G-20 meeting in Mexico, but this time the main topic revolved around solutions to curb the European debt crisis.

In terms of bilateral meetings, Obama made a diplomatic tour between March 19 and 23, 2010 to Brazil, Chile and El Salvador, meeting with their respective presidents. He used the occasion to reestablish relations with the Brazilian left that had governed the country since 2002, to reiterate his economic and political alliance with Chile and to announce a US$200 million fund to strengthen security in Central America. During his second term he made up to seven visits, including the resumption of diplomatic relations with Cuba, which had been paused since the triumph of the Revolution.

Trump: T-MEC

Donald Trump only visited Latin America on one occasion to attend the G-20 meeting , a meeting that was not even regional, held in Buenos Aires in December 2018. Among the various agreements reached were the reform of the World Trade Organization and the commitment of the attendees to implement the measures adopted in the Paris agreement , with the exception of the US, since the president had already reiterated his determination to withdraw from the agreement. Taking advantage of the visit, he signed the T-MEC (Treaty between Mexico, the United States and Canada, the new name for the renewed NAFTA, whose renegotiation had been a Trump demand) and met with the Chinese president in the context of the trade war. Trump, on the other hand, did not attend the VIII Summit of the Americas held in Peru in April 2018; the trip, which was also supposed to take him to Colombia, was canceled at the last minute because the US president preferred to remain in Washington in the face of a possible escalation of the Syrian crisis.

The reason for the few visits to the region has been that Trump has directed his diplomatic campaign towards Europe, Asia and to a lesser extent the Middle East, in the context of the trade war with China and the loss of power in the US international landscape.

Own elaboration with data from the Office of the Historian.

Only one trip, but monitoring of the region

Despite having hardly traveled to the rest of the continent, the Republican candidate has paid attention to the region's affairs, but without leaving Washington, as there have been seven Latin American presidents who have visited the White House. The main focus of the meetings has been economic development and the strengthening of security, as usual. Depending on the reality of each country, the meetings revolved more around the possibility of future trade agreements, the fight against drugs and organized crime, preventing the flow of illegal immigration to the United States or the search to strengthen political alliances. Although the US government website does not list it as an official visit , Donald Trump also met at the White House in February 2020 with Juan Guaidó, recognized as president in charge of Venezuela.

Precisely, if there has been a common topic to all these meetings, it has been the status of the economic and political crisis in Venezuela. Trump has sought allies in the region to encircle and pressure the Maduro government, which is not only an example of continuous human rights violations, but also destabilizes the region. The strong civil service examination the regime served Donald Trump as propaganda to gain popularity and try to save the Latino vote in the November 3 elections, and that had its award at least in the state of Florida.

Own elaboration with data from Office of the Historian.

COMMENTARY / Rafael Calduch Torres*.

As tradition dictates since 1845, on the first Tuesday of November, on the 3rd, the voting inhabitants of the fifty states that make up the United States will take part in the fifty-ninth Election Day, the day on which the Electoral high school is formed, which will have to choose between keeping the forty-fifth President of the United States of America, Donald Trump, or electing the forty-sixth, Joe Biden.

But the real problem facing not only the inhabitants of the USA, but also the rest of the world's population is that both Trump and Biden have their international strategy as a core topic at home, following in the wake of the change that took place in the country after the 9/11 attacks and whose fundamental result has been the absence of effective leadership of the American superpower in the last twenty years. For if there is one thing that must be clear to us, it is the fact that none of the candidates, as their predecessors did not, has a plan that would allow them to resume the international leadership that the United States enjoyed until the end of the 1990s; On the contrary, what urges them is to solve domestic problems and subordinate international issues, which a superpower of the stature of the United States must face, to the solutions adopted internally, which is one of the serious strategic errors of our era, since strong international leaderships that are coherent with the management of domestic problems have historically allowed the creation of meeting points in American society that cushion divisions and bring cohesion to the country.

However, despite these general similarities there is a clear difference between the two candidates when it comes to addressing international issues that will affect the results of the choice Americans will make on Tuesday.

"The Power of America's example". With this slogan, Biden's general proposal , much clearer and more accessible than Trump's, develops a plan to lead the democratic world in the 21st century based on using the way in which America's domestic problems will be solved as an example, binding and sustaining its international leadership; it goes without saying that the mere assumption that the internal problems of the United States are not exactly extrapolable to the rest of the international actors is not even taken into account.

Thus, the Democratic candidate , using a rather traditional rhetoric on the dignity of leadership, uses the connection between domestic and international reality to propose a program of national regeneration without specifying how this will restore the lost international leadership. This approach will be based on two main pillars: the democratic regeneration of the country and the reconstruction of the US class average which, in turn, will make it possible to underpin other international projects.

Democratic regeneration will be based on the strengthening of the educational and judicial systems, transparency, the fight against corruption or the end of attacks on the media, and is proposed as an instrument for the reestablishment of the country's moral leadership which, in addition to inspiring others, would serve for the US to transfer these US national policies to the international arena, for others to follow and imitate them through a sort of global league for democracy that seems very nebulous.

In the meantime, the reconstruction of the class average, the same to which Trump appealed four years ago, would involve greater investment in technological innovation and supposedly greater global equity in international trade, from which the United States would benefit the most.

Finally, all of the above would be complemented by a new era in international arms control through a new START treaty between the US and Russia, US leadership in the fight against climate change, an end to interventions on foreign soil, particularly in Afghanistan, and the reestablishment of diplomacy as the backbone of US foreign policy.

"Promises Made, Promises Kept!What is Trump's alternative? The current President does not reveal what his projects are, but he does propose a review of his "achievements" which, we understand, will give us an idea of what his foreign policy will be, which will revolve around the continuity of the US trade rebalancing based, as up to now, on shielding US companies from foreign investment, the imposition of new tariffs, the fight against fraudulent trade practices, especially by China, and the restoration of US relations with its allies in Asia/Pacific, the Middle East and Europe, but without specific proposals.

With regard to the area of security, treated in a differentiated manner by Trump, the recipe is the increase in defense spending, the shielding of US territory against terrorism and opposition to North Korea, Venezuela and Iran, which will be joined by the maintenance and expansion of the recent campaign of actions directed specifically against Russia, with the declared goal of containing it in Ukraine and preventing cyber-attacks.

But the reality is that both candidates will have to face global challenges that they have not considered in their programs and that will condition them decisively in their mandates, starting with the management of the pandemic and its economic effects on a global scale and including the growing competition from the European Union, especially as its common military and defense capabilities develop.

As we have just seen, none of the candidates will offer new solutions and therefore the situation is not likely to improve, at least in the short term.

* PhD in Contemporary History, graduate in Political Science and Administration. Professor at UNAV and UCJC.

[Iván Garzón, Rebeldes, Románticos y Profetas. La responsabilidad de sacerdotes, políticos e intelectuales en el conflicto armado colombiano (Bogotá: Ariel, 2020) 330 pp].

review / Paola Rosenberg

The book "Rebels, Romantics and Prophets" written by Iván Garzón sample the role played by priests, politicians and intellectuals in the internal armed conflict in Colombia and the responsibility they had in it. A war that marked the country politically, economically, socially and ideologically. Revolutionary movements in Latin America were characterized by the use of violence and the employment weapons to reach power; more or less strong depending on the country, guerrilla groups had in any case a great influence on the course of events in the region during the second half of the twentieth century. The essay by Garzón, professor of Political Theory at the Universidad de La Sabana, focuses especially on the role of the Catholic Church in the different movements and on the contradictory ideas and actions that sustained the conflict over time [he summarizes his purpose in this essay as follows video].

The book "Rebels, Romantics and Prophets" written by Iván Garzón sample the role played by priests, politicians and intellectuals in the internal armed conflict in Colombia and the responsibility they had in it. A war that marked the country politically, economically, socially and ideologically. Revolutionary movements in Latin America were characterized by the use of violence and the employment weapons to reach power; more or less strong depending on the country, guerrilla groups had in any case a great influence on the course of events in the region during the second half of the twentieth century. The essay by Garzón, professor of Political Theory at the Universidad de La Sabana, focuses especially on the role of the Catholic Church in the different movements and on the contradictory ideas and actions that sustained the conflict over time [he summarizes his purpose in this essay as follows video].

"Rebels, Romantics and Prophets" questions and criticizes the responsibility of these groups regarding the resource violence and the use of weapons to achieve social change in Colombia. Iván Garzón challenges the participants of the armed conflict in Colombia to reflect on their role in it and to assume their responsibility to build a better society. In addition, the book aims to open a discussion on the past, present and future of the role and influence of the Catholic Church and intellectuals in society.

The revolutionary waves in Latin America in those years were strengthened by the Marxist ideas of the time. Those ideas defended that the economic development of third world countries was not possible without a rupture of the capitalist market; due to social inequality and class struggle. Therefore, it was necessary to advocate the use of violence in order to come to power. After the triumph of the Cuban revolution in 1959, guerrilla ideas spread rapidly throughout Latin America. Cuba demonstrated that revolution was possible: through armed struggle and Marxist ideas, social development could be achieved. This is how strong revolutionary movements began to emerge in these countries. Colombia was definitely no exception.

One of the young and main protagonists mentioned in the book is Camilo Torres, who was swept up in the revolutionary waves in Colombia. Also known as "the guerrilla priest" or the "Che Guevara of the Christians", Torres was a very influential leader in Colombia in the second half of the 20th century. A guerrilla priest, a hero to some, but a villain to others. Only 37 years old, he died in a troop clash on February 15, 1966, a year after joining the National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrillas. Willing to sacrifice his life and take up arms for his country and social change, Torres affirmed that revolution was inevitable and that it was necessary to contribute to it. Different intellectuals evaluate his figure in the book: some criticize the priest for his "failure" and his incorrect decision to take up arms, others justify him by pointing out that he submitted to a "just war".

Camilo Torres represents the group of rebels, whom the author describes as the "warriors of a failed revolution. They used arms out of an often religious commitment. They justified violence and saw it as a representation of honor, bravery and submission. The rebels decided to take up arms, go out into the bush and join the guerrillas in order to make the Christian faith effective and help the poor. Many of these rebels like Torres focused on Christianity's primary mandate to love their neighbor. They felt an obligation to collaborate in bringing about radical change in the country's political, economic and social Structures . They desired a more just society and sacrificed their lives to achieve it, no matter the means. Many came to the conclusion that the only way to achieve this change was through violent struggle. Their actions sample how the dominant ideas of the time justified the use of violence, going against purely Christian ideas.

In the conflict there was also the group of the "romantics", those who approved of the cause, respected it, but did not get their hands dirty. They were priests, politicians and intellectuals who intervened in the moral and intellectual discussion to justify the reasons for the revolution. They were the passionate ones, the minds behind the acts that directly influenced the warriors who went to the mountains to fight.

Finally, there were the "prophets": the priests, politicians and intellectuals who were completely opposed to armed struggle and the use of violence to bring about change in society. The prophets refused to make a pact with the devil and betray the moral values of the Church. They thought that there were other means to achieve social justice; peaceful and bloodless means. In the end, these were the ones who were right; it was a useless, costly and unwinnable struggle.

In conclusion, both the rebels and the Romantics found in their moral and political views a full justification for the use of violence. The prophets never approved of this cause, but rather criticized it by emphasizing its secularized and contradictory character. Iván Garzón seeks to open a discussion on the legitimacy or illegitimacy of the use of violence as a political means to achieve justice.

Today, the word revolution continues to be linked to violence due to the many traumatic conflicts experienced by many Latin American nations. In Colombia, as in many other countries, the revolutionaries won ideologically, but not in practice. For this reason, it can be concluded that in general, violent internal conflicts only lead to destabilize countries and end innocent lives. The book attempts to make religious and intellectual participants in the armed conflict reflect on their responsibility or guilt in the armed conflict. This discussion between criticism or justification of the armed struggle is still necessary today due to the constant threat to democratic institutions in Latin America.

WORKING PAPER / María del Pilar Cazali

ABSTRACT

The Brexit deal has led to a shift in the UK's relationship not only with the European Union but also with other countries around the world. Africa is key in the new relationships the UK is trying to build outside from the EU due to their historical past, the current Commonwealth link, and the important potential trade deals. This article looks to answer how hard the UK will struggle with competition in the African country as an individual state, no longer member of the EU. These struggles will be especially focused on trading aspects, as they are the most important factors currently for the UK in the post-Brexit era, and it's also the strongest focus of the EU in Africa.

[Peter Zeihan, Desunited Nations. The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World (New York: Harper Collins, 2020) 453 pgs]

October 14, 2020

review / Emili J. Blasco

The world seems to be heading towards what Peter Zeihan calls "the great disorder". His is not a catastrophist vision of the international order for the mere pleasure of wallowing in pessimism, but rather a fully reasoned one. The retreat of the United States is leaving the globe without the ubiquitous presence of the one who ensured the global structure we have known since World War II, forcing other countries into more insecure intercontinental trade and to make a living in an environment of "disunited nations".

The world seems to be heading towards what Peter Zeihan calls "the great disorder". His is not a catastrophist vision of the international order for the mere pleasure of wallowing in pessimism, but rather a fully reasoned one. The retreat of the United States is leaving the globe without the ubiquitous presence of the one who ensured the global structure we have known since World War II, forcing other countries into more insecure intercontinental trade and to make a living in an environment of "disunited nations".

Zeihan has long been drawing consequences from his seminal idea, set out in his first book, The Accidental Superpower (2014): the success of fracking has given the United States energy independence, so it no longer needs Middle Eastern oil and will progressively withdraw from much of the world. In his next book, The Absent Superpower (2016), he detailed how American withdrawal will leave other countries unable to secure important maritime trade routes and reduce the proliferation of developed contacts in this era of globalization. The latter has now been accelerated by the Covid pandemic, which came as a third Issue, Desunited Nations (2020), was about to be published. Zeihan did not have time to include a reference letter to the ravages of the virus, but there was no need because his text was in any case heading in the same direction.

Zeihan, a geopolitical analyst who worked with George Friedman at Stratfor and now has his own signature, studies this time how the different powers will adapt to the "great disorder" and which of them have better prospects. The book is "about what happens when the global order is not only crumbling, but when many leaders feel that their countries will be better off tearing it down. And it's not just a Trump Administration thing: "The push for American retreat didn't start with Trump, nor will it end with him," Zeihan says.

The author believes that, in the new outline, the United States will remain a superpower, China will not reach a hegemonic position and Russia will continue its decline. Among other minor powers, France will lead the new Europe (not Germany; while the British "are doomed to a multi-year depression"), Saudi Arabia will give more concern to the world than Iran and Argentina will have a better future than Brazil.

To focus on the US-China rivalry, it would be good to pick up some of the arguments put forward by Zeihan for his skepticism about the consolidation of the Chinese boom.

To be an effective superpower, China needs greater control of the seas. The problem is not to build a large outward-oriented navy, but, since it is already difficult to sustain such a huge effort over time, it must also have simultaneously "a huge defensive navy and a huge air force and a huge internal security force and a huge army and a huge intelligence system and a huge special forces system and a global deployment capability".

For Zeihan, the question is not whether China will be the next hegemon, which "it cannot be", but "whether China can even hold together as a country". Vectors that work against it are the impossibility of feeding its entire population on its own, the lack of sufficient energy sources of its own, the strong territorial imbalances or demographic constraints, such as the fact that there are 41 million Chinese men under 40 years of age who will never be able to get married.

It is not uncommon for American authors to predict a future collapse of China. However, episodes such as the coronavirus, initially seen as a serious stumbling block for Beijing, never end up cutting short the forward march of the Asian colossus, even though, logically, China's economic growth figures have been moderating over the years. Hence, at times, the bad omens of many could be interpreted more as wishful thinking than as an analysis with sufficient doses of realism. Zeihan certainly writes in a somewhat "loose" way, with blunt statements that seek to shake the reader, but his geopolitical axioms seem to be generally endorsed: if we liquefy well what he says in his three books, we have a clear notice where the world is supposed to be going; and that is where it is indeed going.

COMMENTARY / Juan Luis López Aranguren

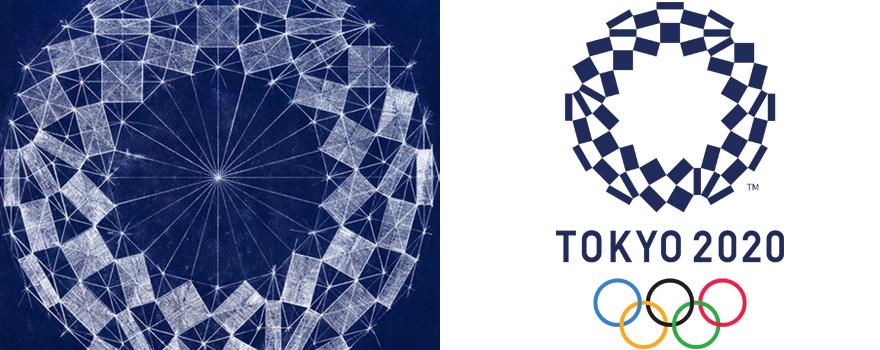

If traditional diplomacy is understood as the relations exercised between official representatives of States, in recent years a new concept of diplomacy has gained popularity and has become increasingly important in relations between nations: cultural diplomacy. Assuming that culture is the vehicle through which nations communicate with each other, cultural diplomacy is the exchange of culture, ideas and information that nations around the world engage in to achieve mutual understanding that will advance the construction of a more just and stable world. In this context, the celebration of the Olympic Games is one of the most important cultural diplomacy events that a nation can achieve to project and share its culture and identity with the rest of the world. In this regard, Japan reaffirmed its position as a global benchmark for this diplomacy with its public appearance at the closing ceremony of the 2016 Rio Olympics. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe appeared in the guise of the world-famous character Mario to pick up the baton for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. Japan thus used an icon of Japanese pop culture to project its cultural identity to the entire planet.

In this dimension of soft power or cultural diplomacy, the Olympic Games are the greatest exponent of it. Already in their origin, in 776 B.C., the Olympic Games revealed themselves as a diplomatic tool of extraordinary strength by forcing a sacred truce between the different city-states that participated in them. Therefore, from its very origin, it was possible to achieve international political objectives by employing this cultural tool . This measure was observed to the point that if any city-state violated this truce, its athletes were expelled from the competition.

This same demonstration has been repeated in more recent times, demonstrating that the Olympics have been a diplomatic battleground throughout history. In 1980 the USA and 65 other countries boycotted the Moscow Olympics in protest against the USSR's invasion of Afghanistan. In retaliation, the USSR and 13 other states boycotted the next Olympics in 1984 in Los Angeles.

The upcoming Tokyo 2021 Olympic Games (delayed one year due to the pandemic) do not carry any controversy of this subject. Instead, they have been conceived as a historic opportunity to reinvent the country internally and globally after the Fukushima catastrophe (or Great East Japan Earthquake). To this end, C official graduate project Tokyo 2020 Action & Legacy Plan 2016 has been designed to achieve three objectives: firstly, to maximize the connection of Japanese citizens and groups with the Tokyo Olympics. Secondly, to maximize cultural projection both nationally and globally. Thirdly and finally, to ensure a bequest of value to future generations, as it was on the occasion of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

These three objectives set by the Japanese government will be expressed in five dimensional pillars on which action will be taken. These five pillars are articulated in the manner of Olympic rings, intertwining with each other and strengthening the domestic and international impact of these Olympic Games. These dimensions are, starting with the most immediate to the purely sporting aspect itself, the promotion of sport and health. The second, connecting with culture and Education. The third, also with great importance for its potential to reform Tokyo in particular and Japan in general, urban planning and sustainability. Not surprisingly, the Japanese government and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government have made great efforts to build ambitious infrastructure to accommodate these Olympics, to the point of relocating the famous and iconic Tsukiji fish market that has been a symbol of the city since 1935. Fourth, the Olympics will be used to revive Economics and technological innovation, just as the 1964 Tokyo Olympics did when it showcased the first Shinkansen, or bullet trains, which have become one of Japan's technological icons. Finally, fifthly, Japan saw the Olympic Games as an opportunity to overcome the crisis and trauma caused by the Fukushima disaster (a catastrophe that in Japan is referred to as the Great East Japan Earthquake).

In addition to these five objectives, ranging from the more specific to the more general, a sixth goal or unofficial dimension will be added in 2020: to project Japan's recovery from the COVID pandemic domestically and internationally. In this sense, the Olympic Games will not only be a symbol of overcoming a particular Japanese disaster, but may allow the Japanese country to position itself as a model in the management against the pandemic and in the promotion of economic recovery.

The deteriorating status of the small Mediterranean country benefits Hezbollah and its patron saint, Iran.

With four different prime ministers so far this year, it is difficult to escape the vicious circle in which Lebanon finds itself, so that the continuity of the current political system and the severe financial crisis seem inevitable. This perpetuation gives rise to a number of possibilities, almost all of them bleak, for the Lebanese future. Here are some of these scenarios.

![State of the port of Beirut after the explosion on August 4, 2020 [Mehr News Agency/Wikipedia]. State of the port of Beirut after the explosion on August 4, 2020 [Mehr News Agency/Wikipedia].](/documents/16800098/0/libano-futuro-blog.jpg/ed561a7d-5d73-93fa-3cbe-2afacd099fac?t=1621884521341&imagePreview=1)

▲ State of the port of Beirut after the explosion on August 4, 2020 [Mehr News Agency/Wikipedia].

article / Salvador Sánchez Tapia

To say that the Lebanese political system is dysfunctional is nothing new. Based on a sectarian balance of power established in 1989 after a long civil war, it perpetuates the existence of clientelistic networks, encourages corruption, hampers the country's economic development and hinders the creation of a cross-cutting Lebanese national identity that transcends religious denominations.

For some time now, Lebanon has been immersed in an economic and social crisis of such magnitude that it has led many analysts to wonder whether we are facing a new case of a failed state. In October 2019, the country was rocked by a wave of demonstrations that the government itself considered unprecedented, unleashed by the advertisement the Executive to address the severe economic crisis with several unpopular measures including taxing the use of the popular Whatsapp application. The protests, initially focused on this issue, soon incorporated complaints against rampant corruption, the uncontrolled increase in the cost of living, or the lack of employment and opportunities in the country.

This popular pressure forced the resignation of the unity government led by Saad Hariri at the end of the same month. The government was replaced in January 2020 by a more technical government led profile former Education Minister Hassan Diab. The new government had little room for maneuver to introduce reforms before the coronavirus pandemic was declared, and soon found itself beset by the same street pressure that had toppled the previous government, with demonstrations continuing despite the restrictions imposed by the pandemic.

The devastating explosion in early August 2020 in the port of Beirut only further plunged the country into the downward spiral into which it was already plunged. Despite the voices that tried to see the hand of Israel or Hezbollah behind the catastrophe that took the lives of 163 people, the Lebanese population soon sensed that this was but the logical consequence of years of corruption, bureaucratic sloppiness and withdrawal the national infrastructure. Again there was a crescendo of popular indignation; again the government was forced to resign at a plenary session of the Executive Council.

With the echoes of the explosion still alive, at the end of August, Mustafa Adib, former Lebanese ambassador to Germany, was entrusted by President Aoun with the task of forming a government. Unable to complete such an arduous task, among other reasons because of Hezbollah's insistence on controlling the Ministry of Finance, Adib resigned on September 26, leaving the country on the brink of the precipice in which it still finds itself.

It is difficult to make predictions about Lebanon's future, beyond predicting that it looks bleak, as a complex dynamic of internal and external forces is gripping the country. Despite the pressure, at least from the urbanized and cosmopolitan Beirut, to put an end to it, it is enormously complex to untangle the dense skein of clientelistic networks that have controlled the country since its independence, not only because of the benefits it has generated for a small group of privileged people, but also because many fear the alternatives to a model that, with all its flaws, has avoided a reproduction of the savage civil war that took place between 1975 and 1990.

Its geographical status makes it difficult for Lebanon to escape the general climate of instability prevailing in the Middle East and the influence exerted on the country by regional and international actors such as Israel, Iran, Syria and France, especially if one considers that the problems of the Levantine state are so deep and its national leadership so weak that it does not seem to be able to overcome them on its own.

The drama of Lebanon is that its own sectarian division makes it difficult for nations to emerge that are willing to donate with cross-cutting criteria to help bridge the gap that divides the country internally, and that the financial aid it may receive from actors such as Iran or Saudi Arabia only reinforces it. The efforts of French President Emmanuel Macron, self-appointed as the driving force behind Lebanese reconstruction, do not seem, for the moment, to be gaining momentum. At the donors' lecture he convened on July 9 with fifteen heads of state, he obtained contributions worth $250 million to revitalize the moribund Lebanese Economics . Meanwhile, the mayor of Beirut estimates the reconstruction costs of the August explosion in the capital's port at between 3 and 5 billion dollars.

As a mirror image of this difficulty, Lebanese communities, comfortably ensconced in the status quo, reject financial aid, no doubt necessary, if they feel it could be detrimental to their respective power instructions . Hezbollah, for example, does not accept IMF programs, complicating the achievement of the necessary national consensus that would facilitate IMF support. It is difficult to escape from this vicious circle, so that the continuation of the current political system, and with it the continuation of the serious Lebanese financial crisis, seems inevitable. From this perpetuation result some possibilities, almost all of them bleak, for the Lebanese future. The first is that Lebanon will continue to slide down the inclined plane that is turning it into a failed state, and that this condition will eventually lead to a civil war precipitated by events similar to those that occurred during the Arab Spring in other states in the region. This eventuality would resurrect the ghosts of the past, produce regional instability that would be difficult to measure but which would undoubtedly provoke the intervention of regional and international actors, and could end up dismembering the country, a result that would only sow the seeds of further instability throughout the region.

Without going to that extreme, the internal disorder could break the precarious balance of power on which Lebanese political life is based, to the benefit of one of its sectarian groups. Hezbollah, the undisputed leader of the country's Shiite faction, appears here as the most organized and strongest group within the country and, therefore, as the one that stands to gain the most from this breakdown. It should be noted that, in addition to the support of the entire 27 internship of Lebanese Shiites, the militia-organization is viewed favorably by many members of the divided Christian community - some 45 percent of the country's population - who put their desire for internal Security Service in the country before other considerations. Aware of this, the leader of Hezbollah, Hasan Nasrallah, sample moderate in his proposals, seeing in the Sunni community, supported by Saudi Arabia, his real rival, and trying to broaden his power base.

Iran would undoubtedly be the real winner in this scenario, since it does not seem realistic to think of a Hezbollah that, once it has come of age, would have a life of its own outside the regime of the ayatollahs. Tehran would complete, with this new piece, the Shiite arc that connects Iran with Iraq and, through Syria, with the Eastern Mediterranean. The destabilizing effects of such a status, however, cannot be underestimated if one takes into account that the mere possibility of the Islamic Republic of Iran gaining absolute control of Lebanon constitutes a casus belli for Israel.

On a positive grade , the serious crisis the country is going through and the strong popular pressure, at least in urban areas, may be, paradoxically, a spur to overcome the sectarian system that has contributed so much to generate this status. However, such a transition only has a chance of advancing - no matter how tenuous - with strong external wholesale support.

In this scenario, the role of the international community should not be limited to the contribution of economic resources to prevent the collapse of the country. Its involvement must favor the development and support of civic-political movements with an intersecting base that are capable of replacing those who perpetuate the current system. To this end, in turn, it is imperative that the contributing nations lend their financial aid in a high-minded manner, renouncing any attempt to shape a Lebanon to suit their respective national interests, and forcing the elites controlling the factions to abdicate the status quo in favor of a true Lebanese identity. The obvious question is: is there any real chance of this happening? The reality, unfortunately, does not allow for high hopes.

Showing 91 to 100 of 426 entries.