Breadcrumb

Blogs

Pandemic reinforces the value of production centers in the same subregions

The free trade zones of Central America and the Caribbean have been an important driving force for the economies of the region. Favored by the increasing globalization of recent decades, they could now be boosted by a phenomenon in the opposite direction: "glocalization", the desirability of having production centers in the same sub-region, close to major markets, to avoid the problems in distant supply chains seen during this Covid-19 crisis that has so affected transportation and communications. The two leading Latin American free trade zone countries, the Dominican Republic and Costa Rica, offer affordable and sufficiently skilled labor at the doorstep of the United States.

![One of the free trade zones of the Dominican Republic [CNZFE]. One of the free trade zones of the Dominican Republic [CNZFE].](/documents/10174/16849987/zonas-francas-blog.jpg)

▲ One of the Dominican Republic's free trade zones [CNZFE].

article / Paola Rosenberg

The so-called free trade zones, also known in some countries as free zones, are strategic areas within a national territory that have certain tax and customs benefits. In them, commercial and industrial activities are carried out under special export and import rules. It is a way of promoting investment and employment, as well as production and exports, thus achieving the economic development of a part of the country or of the country as a whole.

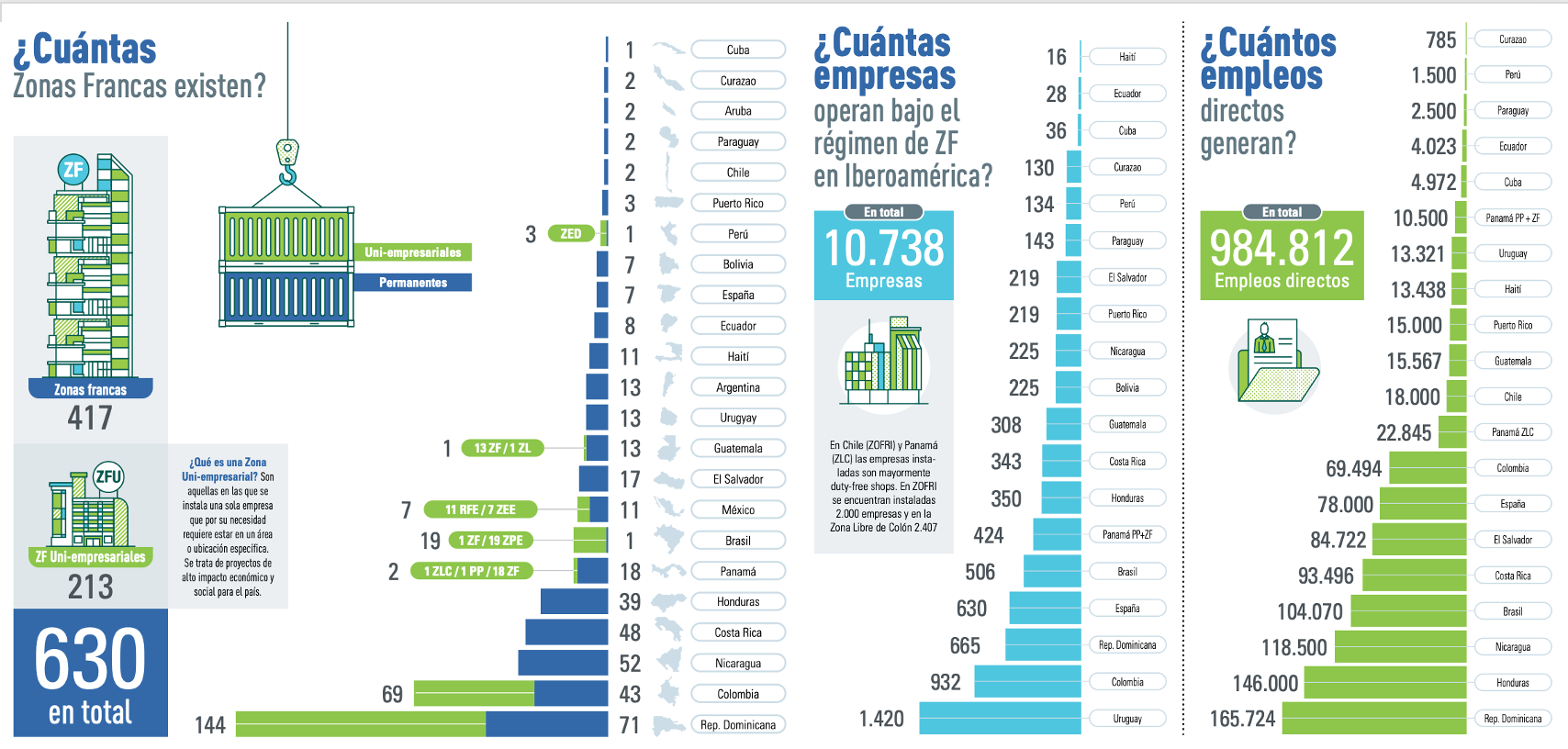

Free trade zones are important in Latin America and, in the case of the smaller economies, they are the main production and export hubs. agreement to the association of Free Trade Zones of the Americas (AZFA), there are some 3,500 free trade zones in the world, of which 400 are in Latin America, representing 11.4% of the total. Within this region, they have a special weight in the countries of Central America and the rest of the Caribbean basin. They are particularly important in the Dominican Republic and Costa Rica, as well as in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Colombia and Uruguay (also in Puerto Rico).

These countries benefit from having abundant labor (especially trained in the Costa Rican case) and at low cost (especially in the Nicaraguan case), and this close to the United States. For manufacturers wishing to enter the U.S. market, it may be interesting to invest in these free trade zones, taking advantage of the tax advantages and labor conditions, while their production will be geographically very close to their destination.

The latter is gaining ground in a post-Covid-19 world. The trend toward subregionalization, in the face of the fractured dynamics of globalization, has been highlighted for other areas of the American continent, as in the case of the Andean Community, but it also makes a great deal of sense for greater integration between the United States and the Greater Caribbean. To the extent that the United States moves towards a certain decoupling from China, the free trade zones in this geographic area may also become more relevant.

Reproduction of the graphic report of the association of Free Trade Zones of the Americas (AZFA), 2018.

Export processing zones

Free zones can be export-oriented (external market), import substitution (internal market) or both. The former may have a high industrial component, either seeking diversification or depending on maquilas, or emphasizing logistics services (in the case of Panama's free zones).

Free zones for exporting products have been particularly successful in the Dominican Republic and Costa Rica. As AZFA indicates, of the $31.208 billion exported from Latin American free zones in 2018, first place went to the Dominicans, with $5.695 billion, and second to Costa Ricans, with $4.729 billion (third place went to Puerto Rico, with $3 billion). Exports from the Dominican Republic's free trade zones accounted for 56% of all exports made by that country; in the case of Costa Rica it was 48% (the third in the ranking was Nicaragua, with 44%).

The Dominican Republic is the country with the highest issue of free trade zones (71 multi-company zones) and its 665 companies generated the highest number of direct jobs (165,724). Costa Rica has 48 free zones (in third position, after Nicaragua), and its 343 companies generated 93,496 direct work (in fifth position).

In terms of the profitability for the country of this economic modality , for every dollar exempted between 2010 and 2015, Costa Rica's free zones generated an average of US$6.2 and US$5 for those of the Dominican Republic (El Salvador ranked second, with US$6).

With specific reference to Costa Rica, a report at the end of 2019 by the Costa Rican foreign trade promotion agency, Procomer, placed the contribution of free trade zones at 7.9% of GDP, generating a total of 172,602 work, both direct and indirect, with annual growth in the issue of jobs averaging 10% per year between 2014 and 2018. These areas account for 12% of the country's formal private sector employment . An important fact about the contribution to the development the local Economics is that 47% of the purchases made by the companies located in the free trade zones were from national companies. An important social dimension is that the zones contributed 508 million dollars to the Costa Rican Social Security Fund in 2018.

The Dominican Republic's free trade zone regime is particularly applauded by the World Bank, which describes the country as a pioneer in this subject productive and commercial promotion instrument, presenting it as "the best-known success story in the Western Hemisphere". agreement to the statistics of the Nationalcommittee of Export Processing Zones (CNZFE), these have contributed in recent years to 3.3% of GDP, thus contributing to the significant growth of the country's Economics in recent years (one of the highest fees in the region, with an average of over 6% until the onset of the current global crisis). The geographical proximity to the United States makes its free trade zones ideal for US companies (almost 40% of investment comes from the US) or for companies from other countries that want to export to the large North American market (34% of exports go to the US).

[Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization. Oxford University Press. Oxford (New York), 2006. 822 p.]

July 2, 2020

review / Salvador Sánchez Tapia

Among the numerous authors who have written on the war phenomenon in recent decades, the name of Azar Gat shines with its own light. From his Chair at Tel-Aviv University, this author has devoted an important part of his academic degree program to theorizing from different angles on the war, a phenomenon that he knows directly from his position as a reservist in the Tsahal (Israel Defense Forces).

Among the numerous authors who have written on the war phenomenon in recent decades, the name of Azar Gat shines with its own light. From his Chair at Tel-Aviv University, this author has devoted an important part of his academic degree program to theorizing from different angles on the war, a phenomenon that he knows directly from his position as a reservist in the Tsahal (Israel Defense Forces).

War in Human Civilization is a monumental work in which the author sample his great erudition, together with his capacity to treat and study the war phenomenon combining the employment fields of knowledge as diverse as history, Economics, biology, archaeology or anthropology, putting them at the service of the goal of his work, which is none other than to elucidate what has moved and moves human groups towards war.

Throughout the almost seven hundred pages of this extensive work, Gat makes a study of the historical evolution of the phenomenon of war in which he combines a chronological approach that we could call "conventional" with a synchronic one in which he puts in parallel similar stages of evolution of war in different civilizations to compare cultures that, at a given historical moment, were in different Degrees of development and show how in all of them war went through a similar process of evolution.

In his initial approach, Gat promises an analysis that transcends any particular culture to consider the evolution of war in a general way, from its beginning to the present day. The promise, however, is broken when he reaches the medieval period because, from that moment on, he adopts a clearly Eurocentric vision that he justifies with the argument that the Western model of war has been exported to other continents and adopted by other cultures, which, without being totally false, leaves the reader with a somewhat incomplete vision of the phenomenon.

Azar Gat dives into the origin of the human species to try to elucidate if the phenomenon of war makes it different from the rest of the species, and to try to determine if conflict is an innate phenomenon in the species or if, on the contrary, it is a learned behavior.

On the first question, the work concludes that nothing makes us different from other species because, despite Rousseaunian visions based on the "good savage" that were so in vogue in the 1960s, the reality sample that intra-species violence, which was considered unique to humans, is in fact something shared with other species. Regarding the second question, Gat adopts an eclectic position according to which aggressiveness would be both innate and optional; a basic survival option that is exercised, however, in an optional manner, and which is developed through social learning.

Throughout the historical journey of the work, the idea, formulated in the first chapters, that the ultimate causes of war are evolutionary in nature and have to do with the struggle for the survival of the species, appears as a leitmotiv.

According to this approach, conflict would have its origin in the competition for resources and better reproductive opportunities. Although human development towards increasingly complex societies has obscured it, this logic would still guide human behavior today, mainly through the bequest of proximate mechanisms involving human desires.

An important chapter in the book is the author's dissection of the theory, first advanced during the Enlightenment, of the Democratic Peace. Gat does not refute the theory, but puts it in a new light. If, in its original definition, it advocates that liberal and democratic regimes are averse to war and that, therefore, the expansion of liberalism will advance peace among nations, Gat argues that it is the growth of wealth that really serves that expansion, and that welfare and the interrelationship favored by trade are the real engines of democratic peace.

Two are, then, the two main conclusions of the work: that conflict is the rule in a nature in which organisms compete with each other for survival and reproduction in an environment of scarce resources, and that, recently, the development of liberalism in the Western world has generated in this environment a feeling of repugnance towards war that translates into an almost absolute rejection of it in favor of other strategies based on cooperation.

Azar Gat recognizes that an important part of the human race is still far from liberal and democratic models, much more from the attainment of the Degree well-being and wealth which, in his view, goes hand in hand with the rejection of war. Although he does not say it openly, it can be inferred from his speech that this is, nevertheless, the direction towards which humanity is heading and that, the day it reaches the necessary conditions for this, war will finally be eradicated from the Earth.

Against this idea, one could argue the ever-present possibility of regression of the liberal system as a result of the demographic pressure to which it is subjected, or because of some global event that provokes it; or that other systems, equally rich but not liberal, replace the world of democracies in world domination.

The work is a must reference letter for any scholar or reader interested in the nature and evolution of the war phenomenon. Written with great erudition, and with a profusion of data that, at times, makes it a bit rough, War in Human Civilization is, without a doubt, an important contribution to the knowledge of war that is essential reading.

finding of a "significant" amount of oil in off-shore wells puts the former Dutch colony on the heels of neighboring Guyana

The intuition has proved to be correct and the prospections carried out under Suriname's territorial waters, together with the successful hydrocarbon reserves being exploited in Guyana's maritime limits, have found abundant oil. The finding could be a decisive boost for the development of what is, after Guyana, the second poorest country in South America, but it could also be an opportunity, as is the case with its neighbor, to accentuate the economic and political corruption that has been hindering the progress of the population.

![Suriname's presidential palace in the country's capital, Paramaribo [Ian Mackenzie]. Suriname's presidential palace in the country's capital, Paramaribo [Ian Mackenzie].](/documents/10174/16849987/surinam-oil-blog.jpg)

▲ Suriname's presidential palace in the country's capital, Paramaribo [Ian Mackenzie].

article / Álvaro de Lecea

So far this year, drilling in two 'off-shore' oil fields in Suriname has result positive, confirming the existence of "significant" oil in block 58, operated by the French company Total, in partnership with the American company Apache. Everything indicates that the same success could be obtained in block 52, operated by the also American ExxonMobil and the Malaysian Petronas, which were pioneers in prospecting in Surinamese waters with operations since 2016.

Both blocks are adjacent to the fields being exploited under the waters of neighboring Guyana, where for the moment it is estimated that there are some 3.2 billion barrels of extractable oil. In the case of Suriname, the prospections carried out in the first viable field, Maka Central-1, discovered in January 2020, speak of 300 million barrels, but the estimates from Sapakara West-1, discovered in April, and subsequent programmed prospections have yet to be added. It is considered that some 15 billion barrels of oil reserves may exist in the Guyana-Suriname basin.

Until this new oil era in the Guianas (the former English and Dutch Guianas; the French Guianas remains an overseas dependency of France), Suriname was considered to have reserves of 99 million barrels, which at the current rate of exploitation left two decades to deplete. In 2016, the country produced just 16,400 barrels per day.

political, economic and social status

With just under 600,000 inhabitants, Suriname is the least populated country in South America. Its Economics depends largely on the export of metals and minerals, especially bauxite. The fall in commodity prices since 2014 particularly affected the country's accounts. In 2015, there was a GDP contraction of 3.4% and 5.6% in 2016. Although the evolution then became positive again, the IMF forecasts for this 2020, in the wake of the global crisis due to Covid-19, a 4.9% drop in GDP.

Since gaining independence in 1975 from the Netherlands, its weak democracy has suffered three coups d'état. Two of them were led by the same person: Desi Bouterse, the country's president until this July. Bouterse staged a coup in 1980 and remained at the helm of power indirectly until 1988. During those years, he kept Suriname under a dictatorship. In 1990 he staged another coup d'état, although this time he resigned the presidency. He was accused of the 1982 murder of 15 political opponents, in a long judicial process that finally ended in December 2019 with a twenty-year prison sentence and is now appealed by Bouterse. He has also been convicted of drug trafficking in the Netherlands, for which the resulting international arrest warrant prevents him from leaving Suriname. His son Dino has also been convicted of drug and arms trafficking and is imprisoned in the United States. Bouterse's Suriname has come to be presented as the paradigm of the mafia state.

In 2010 Desi Bouterse won the elections as candidate of the National Democratic Party (NDP); in 2015 he was re-elected for another five years. In the elections last May 25, despite some controversial measures to limit the options for civil service examination, he lost to Chan Santokhi, leader of the Progressive Reform Party (VHP). He tried to delay the counting and validation of votes, citing the health emergency caused by the coronavirus, but finally at the end of June the new National Assembly was constituted and it should appoint the new president of the country during July.

![Total's operations in Suriname and Guyana waters [Total]. Total's operations in Suriname and Guyana waters [Total].](/documents/10174/16849987/surinam-oil-mapa.png)

Total's operations in Suriname and Guyana waters [Total].

Relationship with Venezuela

Suriname intends to take advantage of this prospect of an oil bonanza to strengthen Staatsolie, the state-owned oil company. In January, before the Covid-19 crisis became widespread, it announced the purpose of expanding its presence in the bond market in 2020 and also, conditions permitting, to list its shares in London or New York. This would serve to raise up to $2 billion to finance the national oil company's exploration campaign in the coming years.

On the other hand, Venezuela's territorial claims against Guyana, which affect the Essequibo -the western half of the former British colony- and which are being studied by the International Court of Justice, include part of the maritime space in which Guyana is extracting oil, but do not affect Suriname, whose delimitations are outside the scope of this old dispute.

Venezuela and Suriname have maintained special relations during Chavismo and while Desi Bouterse has been in power. Occasionally, a certain connection has been pointed out between drug trafficking under the protection of Chavista authorities and that attributed to Bouterse. The offer made by his son to Hezbollah to have training camps in Suriname, a matter for which he was arrested in 2015 in Panama at the request of the United States and tried in New York, can be understood in light of the relationship maintained by Chavism and Hezbollah, to whose operatives Caracas has provided passports to facilitate their movements. Suriname has supported Venezuela in regional forums at times of international pressure against the regime of Nicolás Maduro. In addition, the country has been increasingly strengthening its relations with Russia and China, from which in December 2019 it obtained the commitment of a new credit .

With the political change of the last elections, in principle Maduro's Venezuela loses a close ally, while it may gain an oil competitor (at least as long as Venezuelan oil exploitation remains at a minimum).

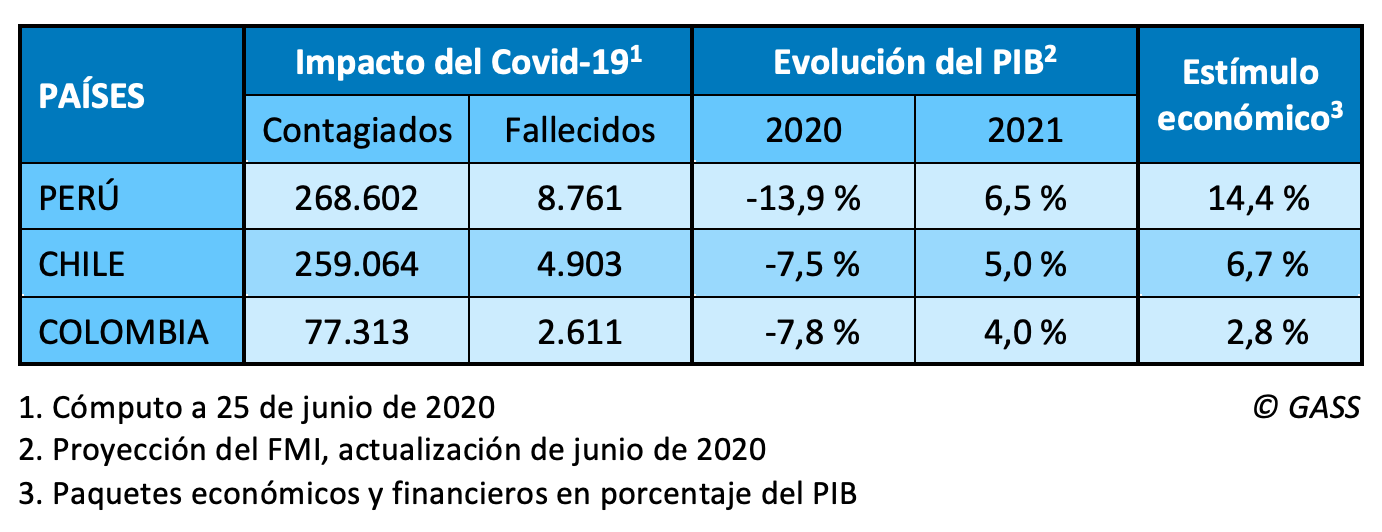

The high incidence of Covid-19 in the country contrasts with the government's swiftness in implementing measures

Peru has been an example in the Covid-19 crisis for its speed in applying containment measures and for approve one of the largest economic stimulus packages in the world, close to 17% of GDP. However, the high incidence of the pandemic, which has made Peru the second Latin American country in coronavirus cases and the third in deaths, has made it necessary to prolong the restrictions on activity longer than expected. This and lower external demand, weaker than initially forecast, have "more than eclipsed" the government's significant economic support, according to the IMF, which forecasts a 13.9% drop in GDP for Peru in 2020, the largest of the region's main economies.

![lecture by Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra (r), in the presence of the head of Economics, María Antonieta Alva (l) [Gov. of Peru]. lecture by Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra (r), in the presence of the head of Economics, María Antonieta Alva (l) [Gov. of Peru].](/documents/10174/16849987/peru-covid-blog.jpg)

lecture by Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra (r), in the presence of the head of Economics, María Antonieta Alva (l) [Gov. of Peru] [Gov. of Peru].

ARTICLE / Gabriela Pajuelo

International media such as Bloomberg y The Wall Street Journal have shown admiration for Peru's young Economics Minister, Maria Antonieta Alva. At 35, after a master's degree from Harvard and some experience in Peru's own administration, Alva designed one of the most ambitious economic stimulus plans in all of South America at the beginning of the crisis.

"From a Latin perspective, Peru is a clear leader in terms of macro response; I could have imagined a very different result if Toni wasn't there," he said. Ricardo Hausmannwho was Alva's professor during his stay at Harvard and leads a team of experts advising Peru and ten other countries to mitigate the effects of the coronavirus. The minister has also become one of the best known faces of President Martin Vizcarra's government among the popular classes.

Peru was one of the first countries in Latin America to apply a state of emergency, limiting freedom of meeting and transit in Peruvian territory and restricting economic activity. To prevent the massive spread of the virus, the government decreed the closure of borders, restrictions on interprovincial movement, a daily curfew and a mandatory period of national isolation, which has been extended several times and has become one of the longest in the world.

This extension, which was agreed upon due to the high incidence of the pandemic, has damaged the economic outlook more than expected. In addition, the prolongation of the emergency in countries to which Peruvian exports are destined has weakened their demand for raw materials and damaged the resurgence of Peru's Economics . This is what the IMF estimates, which between its April forecast and the one updated in June has added nine more points to the fall in Peruvian GDP for 2020. The IMF now considers that Peruvian Economics will fall by 13.9% this year, the highest among the region's main countries. Although the ambitious stimulus package will not have prevented this decline, it will boost the recovery, with a GDP increase of 6.5% in 2021, in turn the strongest rebound among the largest Latin American economies. Regarding this last forecast, the IMF specifies that, nevertheless, "there are significant leave risks, linked to national and global challenges to control the epidemic".

A socioeconomic context that does not financial aid to confinement

Despite restrictive social distancing measures, the pandemic has had a high incidence in Peru, with 268,602 diagnosed cases (in Latin America, second only to Brazil) and 8,761 deaths (behind Brazil and Mexico) as of June 25. These high figures are partly due to the fact that the country's socioeconomic conditions have meant that compliance with containment has not been very strict in certain situations. The social context has hindered compliance with mandatory quarantine due to structural problems such as the fragility of health services and infrastructure, the difficulty in making efficient public purchases, prison overcrowding and the digital divide.

The high level of labor informalityThe fact that in 2019 it was 72%, explains why many people must continue working to ensure their subsistence, without following certain protocols or access to certain material; at the same time, this informality prevents greater tax collection that would help to improve budget items such as healthcare. Peru is the second Latin American country with the lowest investment in healthcare.

On the other hand, inequalityThe Gini index, which in 2018 was 42.8, is aggravated by the territorial distribution of the expense, linked to the centralization of employment of the rural population in Lima. During the pandemic, workers from the country's highlands who have migrated to the capital have wanted to return to their places of origin, as many are not on the payroll and do not have labor rights, in contravention of mobility restrictions.

This social context makes it possible to question some of the approved economic measures, according to some Peruvian academics. The president of the Peruvian Institute of Economics (IPE), Roberto Abusada, warned that Peru's macroeconomic strengths will not help forever. He considered that certain regulations cannot be complied withThe "setting parameters such as body mass index (BMI) or an age limit generates obstacles for this group of people, who could be highly qualified, and could not return to their workcenter".

Economic package

At the end of April, Minister Alva presented a $26 billion economic stimulus package, representing 12% of GDP. Additional measures raised this percentage to 14.4% of GDP a month later, and even then it would have been closer to 17%. Comparatively, this is one of the largest stimulus packages adopted in the world (in Latin America, the second country is Brazil, with a stimulus of 11.5% of GDP).

In agreement with the monitoring that the IMF Peru has adopted measures in three different areas: fiscal, monetary and macro-financial, and in terms of the exchange rate and balance of payments.

First, in terms of fiscal measures, the government approved 1.1 billion soles (0.14% of GDP) to address the health emergency. In addition, different measures have been implemented, among which two stand out: the "Stay in your home" bonus and the creation of the Business Support Fund for Micro and Small Enterprises (FAE-MYPE).

The first measure, for which the government approved approximately 3.4 billion soles (0.4% of GDP) in direct transfers, is a 380 soles (US$110) bond, targeted at poor households and vulnerable populations, of which there have been two disbursements. The second measure refers to the creation of a fund of 300 million soles (0.04% of GDP) to support MSEs, in an attempt to guarantee credit for work capital and to restructure or refinance their debts.

Among other fiscal measures, the government approved a three-month extension of the income tax declaration for SMEs, some flexibility for companies and households in the payment of tax obligations, and a deferral of household electricity and water payments. The entire fiscal support package accounts for more than 7% of GDP.

On the other hand, in terms of monetary and macro-financial measures, the Central reservation Bank (BCR) reduced the reserve requirement rate by 200 basis points, bringing it to 4%, and is monitoring the evolution of inflation and its determinants to increase monetary stimulus if necessary. It has also reduced reserve requirements , provided liquidity to the system with a package backed by government guarantees of 60 billion soles (more than 8% of GDP) to support loans and the chain of payments.

In addition, exchange rate and balance of payments measures have been implemented through the BCR's intervention in the foreign exchange market. By May 28, the BCR had sold approximately US$2 billion (0.9% of GDP) in foreign exchange swaps. International reserves remain significant at over 30% of GDP.

On the other hand, in the area of trade relations, Peru agreed not to impose restrictions on foreign trade operations, while liberalizing the loading of goods, speeding up the issuance of certificates of origin, temporarily eliminating some tariffs and waiving various infractions and penalties contained in the General Customs Law. This was especially true for transactions with strategic partners, as the European UnionAccording to Alberto Almendres, the president of Eurochambres (the association of European Chambers in Peru). 50% of foreign investment in Peru comes from Europe.

Peruvian exports, although the emergence of the coronavirus in China at the beginning of the year led to a slowdown in transactions with that country, mining and agricultural exports remained positive. in the first two months of the yearas indicated by the research and development Institute of Foreign Trade of the Lima Chamber of Commerce (Idexcam). Subsequently, the impact has been greater, especially in the case of raw material exports and tourism.

Comparison with Chile and Colombia

The status in Peru can be analyzed in comparison with its neighbors Chile and Colombia, which will have a somewhat smaller drop in GDP in 2020, although their recovery will also be somewhat smaller.

In terms of the issue of confirmed Covid-19 cases as of June 25, Chile (259,064 cases) is similar in size to Peru (268,602), although the issue of deaths is almost half (4,903 Chileans and 8,761 Peruvians), which corresponds to the proportion of its total population.

In response to the pandemic, Chilean authorities implemented a series of measures, including the declaration of a state of catastrophe, travel restrictions, school closures, curfews and bans on public gatherings, and a telework law. This crisis came only a few months after the social unrest experienced in the country in the last quarter of 2019.

On the economic front, Chile approved a stimulus of 6.7% of GDP. On March 19, the authorities presented a fiscal package of up to US$11.75 billion focused on supporting corporate employment and liquidity (4.7% of OPIB), and on April 8, an additional US$2 billion of financial aid to vulnerable households was announced, as well as a credit guarantee scheme of US$3 billion (2%). In its June forecast update , the IMF expects Chile's GDP to fall by 7.5% in 2020 and increase by 5% in 2021.

As for Colombia, the level of contagion has been lower (77,313 cases and 2,611 deaths), and its economic package to deal with the crisis has also been smaller: 2.8% of GDP. The Government created a National Emergency Mitigation Fund, which will be partially financed by regional and stabilization funds (about 1.5% of GDP), complemented by the issuance of national bonds and other budgetary resources (1.3%). In its recent update, the IMF forecasts that Colombia's GDP will fall by 7.8% in 2020 and rise by 4% in 2021.

[Tae-Hwan Kwak and Seung-Ho Joo (eds). One Korea: visions of Korean unification. Routledge. New York, 2017. 234 p.]

review / Eduardo Uranga

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, tensions between superpowers in East Asia made this part of the world a hot spot in International Relations. Tensions remain today, such as the trade war that since 2018 has pitted the United States and the People's Republic of China against each other. However, over the past 70 years, one territory in particular has been affected by a continuing conflict that has several times claimed the world's attention. This region is undoubtedly the Korean peninsula.

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, tensions between superpowers in East Asia made this part of the world a hot spot in International Relations. Tensions remain today, such as the trade war that since 2018 has pitted the United States and the People's Republic of China against each other. However, over the past 70 years, one territory in particular has been affected by a continuing conflict that has several times claimed the world's attention. This region is undoubtedly the Korean peninsula.

This book, co-edited by Tae-Hwan Kwak and Seung-Ho Joo and bringing together various experts on inter-Korean relations, outlines the various possibilities of a future reunification of the two Koreas, as well as the various problems that need to be solved in order to achieve this goal. The perspectives of the various world powers on the conflict are also analyzed.

The Korean issue comes from World War II: after the country was occupied by Japan, its liberation ended up dividing the peninsula in two: North Korea (occupied by the Soviet Union) and South Korea (controlled by the United States). Between 1950 and 1953, the two halves fought a conflict, which eventually consolidated the partition, with a demilitarized zone in between known as the 38th Parallel or KDZ.

One of the formulas for Korean unification described in this book is unification through neutralization, proposal by both Koreas. However, the constant long-range nuclear missile tests conducted by North Korea in recent years present a major obstacle to this formula. In this atmosphere of mistrust, Korean citizens play an important role in promoting cooperation and friendship on both sides of the border with the goal of achieving the denuclearization of North Korea.

Another aspect that plays an important role in forcing a change in North Korea's attitude is its strategic culture. This must be differentiated from the traditional Korean strategic culture. North Korea has adopted various unification strategies over the years while maintaining the same principles and values. This strategic culture blends elements from the country's strategic position (geopolitically), history and national values. All this under the authority of the Juche ideology. This ideology contains some militaristic elements and promotes the unification of Korea through armed conflict and revolutionary actions.

As for the perspectives of the various world superpowers on a future Korean reunification, China has stated that it favors unification in the long term; a process undertaken in the short term would collide with Chinese national interests, as Beijing would first have to settle its disputes with Taiwan, or end the trade war against the United States. China has stated that it will not accept Korean unification influenced by a military alliance between the United States and South Korea.

On the other hand, the United States has not yet opted for a specific Korean unification policy. Since the 1950s, the Korean peninsula has been but one part of the overall U.S. strategic policy for the entire Asia Pacific region.

The unification of the Korean peninsula will be truncated as long as the United States, China and other powers in the region continue to recognize the status quo on the peninsula. It could be argued that perhaps an armed conflict would be the only way to achieve unification. According to the authors of this book, this would be too costly in terms of resources used and human lives lost. On the other hand, such a war could trigger a conflict on a global scale.

The trade dependence between the two countries - greater in the case of Brazil, but the Chinese also need certain Brazilian products, such as soybeans - ensures the understanding between the two countries.

The relationship between Brazil and China has proven to be particularly pragmatic: neither Jair Bolsonaro has reviewed the link with the Asian country as he promised before becoming president (in his first year in office he has not only kept Brazil in the BRICS but even made a highly publicized official trip to Beijing), nor has Xi Jinping punished his partner for having accused him of mismanaging the coronavirus pandemic, as has happened with other countries. The convenience of mutual trade relations, revalued by the trade war between China and the US and by the present world crisis, has prevailed.

![Jair Bolsonaro and Xi Jinping in Beijing in October 2019 [Planalto Palace]. Jair Bolsonaro and Xi Jinping in Beijing in October 2019 [Planalto Palace].](/documents/10174/16849987/pragmatismo-china-blog.jpg)

▲ Jair Bolsonaro and Xi Jinping in Beijing in October 2019 [Planalto Palace].

article / Túlio Dias de Assis

After years of criticizing the "perverse communist government of Beijing", Jair Bolsonaro surprised at the end of last October with a state visit to the Forbidden City, which he himself specially publicized on social networks. On that trip he gave Xi Jinping the jersey of the Club de Regatas do Flamengo (the soccer team that at that time represented Brazil in the Libertadores Cup, which he would end up winning) and expressed his total conviction of being in a capitalist country. In November he hosted a BRICS summit in Brasilia.

Bolsonaro's policy toward China had already begun to change since shortly after acceding to the presidency in January 2019, in contrast to his anti-China messages during the election campaign.

In fact, diplomatic relations between the two countries date back to the time of the military board of which Bolsonaro sample so proud. In 1974, Brazil recognized the People's Republic of China as the only China, thus allowing, despite being unaware of it at the time, the creation of a huge trade link between the two nations of continental proportions. Since then, as China's openness to China progressed, relations between China and Brazil have been increasing, so that for almost a decade now China has been Brazil's main trading partner . China's dependence on Brazil is also remarkable in relation to some products, such as soybeans, although for the Chinese Brazil is the twentieth trading partner , since logically they are economies of very different sizes.

When in 1978 Deng Xiaoping decided to open up Chinese Economics to the rest of the world, Chinese GDP was close to $150 billion, 75% of Brazil's, which was already over $200 billion. Four decades later, in 2018, Brazilian GDP was $1.8 trillion and Chinese GDP was $13.6 trillion.

Soybeans and swine

Brazil's greatest commercial and even political rapprochement with China occurred during the presidency of Luiz Inácio 'Lula' da Silva, during which the BRICS was formed, a club that helped create a greater level of economic and diplomatic proximity between member countries. This rapprochement led China to become Brazil's leading trading partner in terms of exports and imports. Brazil's sales to China almost double exports to the US.

Although trade with Brazil represents less than 4% of the total value of goods imported by China annually, the South American country continues to be an important trading partner for the People's Republic, due to the fact that the main product imported from Brazil is soybeans, one of the usual per diem expenses instructions for a large part of the Chinese population. More than half of the soybeans imported by China come from Brazil and the trend is to increase, mainly due to the trade war with the USA - the second main exporter of soybeans to China -, thus making Brazil practically the breadbasket of the Middle Kingdom. China is the destination of more than 70% of Brazilian soybean production.

Dependence on China, from the Brazilian consumer's perspective, was accentuated at the end of 2019 due to an exorbitant rise in the price of meat. The average between the different Brazilian states hovered between 30% and 40% compared to previous months. Producers were able to substantially increase their profits in the short term, but the popular classes openly protested the uncontrolled price of a product very present in the usual per diem expenses of the average Brazilian. The rise in prices was due to a combination of factors, among them an outbreak of swine fever that devastated a large part of Chinese production. Faced with a shortage of supply in its domestic market, China was forced to diversify its suppliers, and being in the midst of a trade war with the USA, China had no choice but to turn to the Brazilian agricultural potential, one of the few capable of meeting the great Chinese demand for meat. During this period - a brief one, as it gradually returned to the previous status - Brazil obtained a certain coercive power over the Asian giant.

Huawei and credits

Brazil is in a status of extreme dependence on China in technological subject : more than 40% of Brazil's purchases from China are machinery, electronic devices or parts thereof. Already in the last decade, with the arrival of the smartphone and fiber optics revolution in Latin America, Brazil decided to bet more on Chinese technology, thus becoming one of the main international markets for the now controversial Huawei brand, which has come to dominate 35% of the Brazilian cell phone market. While the US and Europe were suspicious of Huawei and from the beginning placed limits on its markets, Brazil saw Chinese technology as a cheaper way to develop and never let itself be swayed by suspicions of Chinese government interference in privacy subject . Even several deputies of the PSL (former party to which Bolsonaro belonged) visited China in early 2020 to evaluate the possibility of acquiring Chinese facial recognition equipment to help state security forces in the fight against organized crime, a proposal that was ultimately rejected by the Parliament.

With the rise of the controversy about the risks of espionage that the use of the Chinese multinational's technology may pose, some voices have warned of the threat that Huawei's contracting may pose to many government agencies and offices: a couple of embassies and consulates, part of the infrastructure of the Chamber of Deputies, and even the headquarters of the Federal Prosecutor's Office and the Federal Justice in some federal states. Although given the lack of accusatory evidence against Huawei, little has been done by the government about it; only the cancellation of some purchases of Huawei devices has been given.

Brazil is the country that has received the second most public loans from China in Latin America: $28.9 billion (Venezuela is the first with $62.2 billion), spread over eleven loans between 2007 and 2017, of which nine come from the Chinese development Bank and two others from the Export-Import Bank of China. Despite being a high value, it represents a very small percentage of the Brazilian public debt, which already exceeds one trillion dollars. Most of the loans granted by Beijing have been earmarked for the construction of infrastructure for resource extraction. In addition, Chinese companies have invested in the construction of two ports in Brazil, one in São Luís (Maranhão State) and the other in Paranaguá (Paraná State).

Coronavirus rhetoric

Bolsonaro soon realized his dependence on China and opted for a policy of accommodation towards Beijing, far from his election campaign messages. Once again, then, Brazil was betting on pragmatism and moderation, as opposed to ideology and radicalism, in terms of Itamaraty (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) policy. Likewise, in the face of the instability caused by the US-China trade war and Trump's current weak position, Bolsonaro was demonstrating pragmatism by not closing himself off to high-potential trade partners because of his ideology, as was seen last November at the BRICS summit in Brasilia.

But sometimes a rhetoric emerges that is in line with the original thinking. In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, Bolsonaro has copied Trump's anti-China narrative in some messages. A good example is the exchange of tweets that took place between Eduardo Bolsonaro, federal deputy and eldest son of the president, and the Chinese ambassador, Yang Wanming. The former compared the coronavirus to the Chernobyl accident, insinuating total irresponsibility, negligence and concealed information on the part of the Chinese Communist Party. The ambassador responded that the president's son "on his last trip to the US did not contract the coronavirus, but a mental virus", referring to his ideological proximity to Trump.

However, all this status seems to have calmed down after a call between the presidents of both countries, in which both reaffirmed their commitments, especially those of a commercial and financial nature. Also, once again Bolsonaro seems to follow Itamaraty's traditional line of neutrality, despite the constant insistence of his instructions to blame China for the current tragedy. It is clear that the economic dependence on China is still much stronger than the ideological principles of Bolsonaro's political base, however Trumpist it may be.

![VCR 8x8 Programframework Romero/MDE]. VCR 8x8 Programframework Romero/MDE].](/documents/10174/16849987/ddn-blog.jpg)

▲ VCR 8x8 programframework Romero/MDE].

COMMENTARY / Salvador Sánchez Tapia

After a gap of eight years since the publication of the last one in 2012, last June 11, the President of the Government signed a new National Defense Directive (DDN), thus marking the beginning of a new Defense Planning cycle which, in agreement with the provisions of Defense Order 60/2015, must be valid for six years.

The DDN 20 essay is a praiseworthy effort to bring National Defense up to date in order to adapt to the challenges of a complex strategic environment in continuous transformation. Your essay also offers an excellent opportunity to build along the way an intellectual community on such a relevant issue, which will be fundamental throughout the cycle.

This article provides a preliminary analysis of the DDN 20 focusing on its most relevant aspects. In a first approach, the official document follows the line, already enshrined in other Directives, of subsuming the essentially military concept of Defense within the broader concept of Security, which affects all the capabilities of the State. In this sense, the first difficulty that the DDN 20 has had to overcome is precisely the lack of a statutory document similar to the DDN, drafted at the level of National Security, to illuminate and guide it. To tell the truth, the void has not been total, since, as stated by the DDN 20 in its introduction, there is a National Security Strategy (ESN) which, although published in 2017, has served as a reference letter in its elaboration, despite the evident lack of consistency that can be seen between the strategic scenarios described in both documents.

In this regard, it is worth noting the lack of specificity with which the new DDN defines the strategic scenario, in comparison with the somewhat greater specificity of the ESN. The DDN 20 draws a vague, almost generic scenario, applicable almost unchanged to any nation in the world, without reference to specific geographical areas; an accumulation of threats and risks to security with an impact on defense, none of which appears to be more likely or more dangerous, and to which is added the recognition of changes in the international order that once again bring the possibility of major armed conflicts closer.

Such an approach makes it difficult to subsequently define defense objectives and guidelines for action and, perhaps for this reason, certain inconsistencies can be observed among the three parts of the document. It is striking that, although the document raises the somewhat hasty certificate of the emergence of COVID-19, the possibility of a pandemic not being triggered is not considered in the description of the strategic scenario, something that, on the other hand, is included in ESN 17.

Along with the description of this scenario, the DDN 20 is interspersed with a set of considerations of a programmatic nature, in themselves positive and relevant, but which have little to do with what is to be expected in a document of this nature, designed to guide the planning of National Defense. In some cases, such as the promotion of the gender perspective, or the improvement of the quality of life of the staff in its dimensions of improving living facilities, reconciliation of professional and family life, and reintegration into civilian life once the link with the Armed Forces has ended, the considerations are more typical of the department 's staff Policy than of a DDN. In others, such as the obligation to respect local cultures in military operations, they seem to be more the subject of the Royal Ordinances or another subject of a code of ethics.

Undoubtedly motivated by the COVID-19 emergency, and in view of the role that the Armed Forces have assumed during it, the DDN emphasizes the importance of partnership missions with and support to civilian authorities, something, moreover, consubstantial to the Armed Forces, and establishes the specific goal of acquiring capabilities that enable partnership and support to such authorities in crisis and emergency situations.

The management the pandemic may have highlighted gaps in response capabilities, shortcomings in coordination tools, etc., thus opening a window of opportunity to make progress in this area and produce a more effective response in the future. However, it is advisable to guard against the possibility, open in this DDN, of losing sight of the central tasks of the Armed Forces, to prevent an excessive focus on missions in support of the civilian population from ending up distorting their organization, manning and training, thereby impairing the deterrence capacity of the armies and their combat operability.

The DDN also contains the usual reference letter, obligatory and necessary, to the promotion among Spaniards of a true Defense Culture. The accredited specialization is justified by the role that the Ministry of Defense must play in this effort. However, it is not the field of defense that needs to be reminded of the importance of this issue. The impact of any effort to promote the Culture of Defense will be limited if it is not assumed as its own by other ministerial Departments , as well as by all the administrations of the State, being also aware that it is not possible to generate a Culture of Defense without a prior consensus at the national level on such essential issues as the objectives or values shared by all. It is, perhaps, on this aspect that the emphasis should be placed.

Perhaps the most controversial point of the DDN 20 is that of financing. Achieving the objectives set out in the document requires a sustained financial investment over time that breaks the current ceiling on defense expense . Maintaining the Armed Forces among the technological elite, substantially improving the quality of life of the professional staff -which begins by providing them with the equipment that best guarantees their survival and superiority on the battlefield-, reinforcing the capacity to support civilian authorities in emergency situations, strengthening intelligence and cyberspace capabilities, or meeting with guarantees the operational obligations derived from our active participation in international organizations which, moreover, are committed to be reinforced by up to 50% for a period of one year, is as necessary as it is costly.

The final paragraph of DDN 20 recognizes this when it states that the development the document's guidelines will require the necessary funding. This statement, however, is little more than an acknowledgement of the obvious, and is not accompanied by any commitment or guarantee of funding. Taking into account the important commitments already subscribed by the Ministry with the pending Special Armament Programs, and in view of the economic-financial panorama that is on the horizon due to the effects of COVID-19, which has led the JEME to announce to the Army the arrival of a period of austerity, and which would deserve to be included among the main threats to national security, it seems difficult that the objectives of the DDN 20 can be covered in the terms that it proposes. This is the real Achilles' heel of the document, which may turn it into little more than a dead letter.

In conclusion, the issuance of a new DDN is to be welcomed as an effort to update the National Defense policy, even in the absence of a similar instrument that periodically articulates the level of the Security Policy, in which the Defense Policy should be subsumed.

The emergence of COVID-19 seems to have overtaken the document, causing it to lose some of its validity and calling into question not only the will, but also the real capacity to achieve the ambitious objectives it proposes. At least it is possible that the document may act, even in a limited way, as a sort of shield to protect the defense sector against the scenario of scarce resources that Spain will undoubtedly experience in the coming years.

[John West, Asian Century on A Knife Edge: A 360 Degree Analysis of Asia's Recent Economic Development.. Palgrave Macmillan. Singapore, 2018. 329 p.]

REVIEW / Gabriela Pajuelo

The degree scroll of this book seems to contribute to the generalized chorus that the 21st century is the century of Asia. In reality, the book's thesis is the opposite, or at least it puts that statement "on the razor's edge": Asia is a continent of great economic complexity and conflicting geopolitical interests, which poses a series of challenges whose resolution will determine the region's place in the world in the coming decades. For the time being, according to John West, a university professor in Tokyo, nothing is certain.

The book begins with a preamble on the recent history of Asia, from World War II to the present. Already at the beginning of that period, economic liberalism was established as the standard doctrine in much of the world, including most Asian countries, in a process driven by the establishment of international institutions.

China joined this system, without renouncing its internal doctrines, when it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. Since then, there have been some shocks such as the financial crisis of 2007-2008, which severely affected the U.S. economy and had repercussions in the rest of the world, or the recent tariff tensions between Washington and Beijing, in addition to the current global crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

The principles of protectionism and nationalism deployed by Donald Trump and an increased U.S. resource to the hard power in the region, as well as a more assertive policy of Xi Jinping's China in its geographical environment, also resorting to positions of force, as in the South China Sea, have damaged the multilateralism that had been built up in that part of the world.

The author provides some thought-provoking ideas on the challenges that Asia will face, given that the core topic factors that favored its development have now deteriorated (mainly due to the stability provided by international economic interdependence).

West examines seven challenges. The first is to obtain a better position in global value chains, since since the 1980s the manufacture of components and the production of final products has taken place in different parts of the world. Asia is heavily involved in these supply chains, in fields such as technology and apparel production, but is subject to the business decisions of multinationals whose practices are sometimes not socially responsible and allow the abuse of labor rights, which are important for middle-class development .

The second challenge is to maximize the potential of urbanization, which has grown from 27% of the population in 1980 to 48% in 2015. The region is known for densely populated megacities. This brings with it some difficulties: the population migrating to industrial centers generally moves from leave to high-productivity jobs, and health care capacity is put to the test . But it is also an opportunity to improve environmental practices or encourage innovation through green technologies, even though much of Asia today still faces high levels of pollution.

Another challenge is to give all Asians equal opportunities in their respective societies, from LGBT people to women and indigenous communities, as well as ethnic and religious minorities. The region also faces a major demographic challenge , as many populations either age (such as China's, despite the correction of the "two-child policy") or continue to expand with presumed future supply problems (as in the case of India).

West also reference letter to the barriers to democratization that exist in the region, with China's notable immobility, and to the spread of economic crime and corruption (counterfeiting, piracy, drug trafficking, human trafficking, cybercrime and money laundering).

Finally, the author speaks of the challenge for Asian countries to live together in peace and harmony, while China consolidates its position as a regional leader: if there is a Chinese commitment to thesoft powerThrough the Belt and Road initiative, there is also a more confrontational attitude on the part of Beijing towards Taiwan, Hong Kong and the South China Sea, while players such as India, Japan and North Korea want a greater role.

Overall, the book offers a comprehensive analysis of Asia's economic and social development and the challenges ahead. In addition, the author offers some thought-provoking ideas, arguing that a so-called "Asian century" is unlikely due to the region's lagging economic development , as most countries have not caught up with their Western counterparts in terms of GDP per capita and technological sophistication. Nevertheless, it leaves the future open: if the challenges are successfully met, the time may indeed come for an Asian Century.

![Flood rescue in the Afghan village of Jalalabad, in 2010 [NATO]. Flood rescue in the Afghan village of Jalalabad, in 2010 [NATO].](/documents/10174/16849987/climate-refugees-blog.jpg)

▲ Flood rescue in the Afghan village of Jalalabad, in 2010 [NATO].

June 16, 2020

ESSAY / Alejandro J. Alfonso

In December of 2019, Madrid hosted the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP25, in an effort to raise awareness and induce action to combat the effects of climate change and global warming. COP25 is another conference in a long line of efforts to combat climate change, including the Kyoto Protocol of 2005 and the Paris Agreement in 2016. However, what the International Community has failed to do in these conferences and agreements is address the issue of those displaced by the adverse effects of Climate Change, what some call "Climate Refugees".

Introduction

In 1951, six years after the conclusion of the Second World War and three years after the creation of the State of Israel, a young organization called the United Nations held an international convention on the status of refugees. According to Article 1 section A of this convention, the status of refugee would be given to those already recognized as refugees by earlier conventions, dating back to the League of Nations, and those who were affected "as a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion...". However, as this is such a narrow definition of a refugee, the UN reconvened in 1967 to remove the geographical and time restrictions found in the 1951 convention[1], thus creating the 1967 Protocol.

Since then, the United Nations General Assembly and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have worked together to promote the rights of refugees and to continue the fight against the root causes of refugee movements.[2] In 2016, the General Assembly made the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, followed by the Global Compact on Refugees in 2018, in which four objectives were established: "(i) ease pressures on host countries; (ii) enhance refugee self-reliance; (iii) expand access to third country solutions; and (iv) support conditions in countries of origin for return in safety and dignity".[3] Defined as 'interlinked and interdependent objectives', the Global Compact aims to unite the political will of the International Community and other major stakeholders in order to have 'equitalized, sustained and predictable contributions' towards refugee relief efforts. Taking a holistic approach, the Compact recognizes that various factors may affect refugee movements, and that several interlinked solutions are needed to combat these root causes.

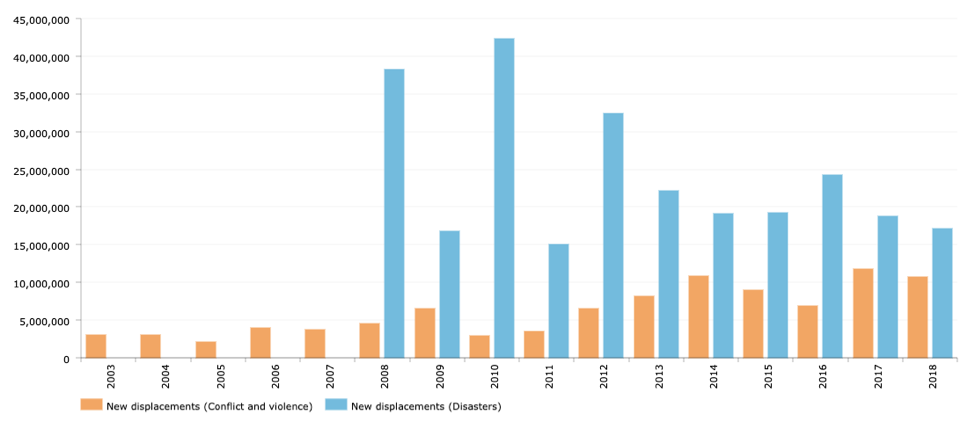

While the UN and its supporting bodies have made an effort to expand international protection of refugees, the definition on the status of refugees remains largely untouched since its initial applications in 1951 and 1967. "While not in themselves causes of refugee movements, climate, environmental degradation and natural disasters increasingly interact with the drivers of refugee movements".3 The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has found that the increase of the average temperature of the planet, commonly known as Global Warming, can lead to an increase in the intensity and occurrence of natural disasters[4]. Furthermore, this is reinforced by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, which has found that the number of those displaced by natural disasters is higher than the number of those displaced by violence or conflict on a yearly basis[5], as shown in Table 1. In an era in which there is great preoccupation and worry concerning the adverse effects of climate change and global warming, the UN has not expanded its definition of refugee to encapsulate those who are displaced due to natural disasters caused by, allegedly, climate change.

Table 1 / Global Internal Displacement Database, from IDMC

Methodology

This present paper will be focused on the study of Central America and Southeast Asia as my study subjects. The first reason for which these two regions have been selected is that both are the first and second most disaster prone areas in the world[6], respectively. Secondly, the countries found within these areas can be considered as developing states, with infrastructural, economic, and political issues that can be aggravating factors. Finally, both have been selected due to the hegemonic powers within those hemispheres: the United States of America and the People's Republic of China. Both of these powers have an interest in how a 'refugee' is defined due to concerns over these two regions, and worries over becoming receiving countries to refugee flows.

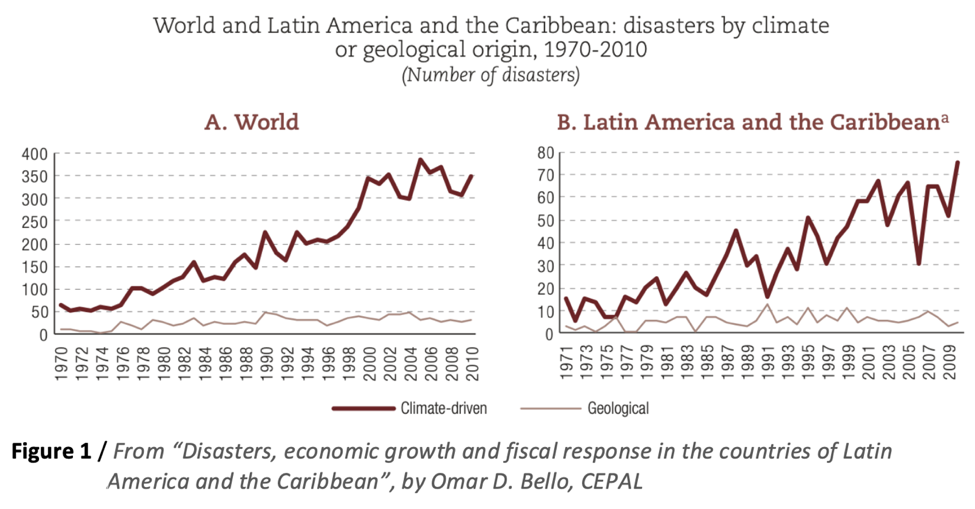

Central America

As aforementioned, the intensity and frequency of natural disasters are expected to increase due to irregularities brought upon by an increase in the average temperature of the ocean. Figure 1 shows that climate driven disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean have slowly been increasing since the 1970s, along with the world average, and are expected to increase further in the years to come. In a study by Omar D. Bello, the rate of climate related disasters in Central America increased by 326% from the year 1970 to 1999, while from 2000 to 2009 the total number of climate disasters were 143 and 148 in Central America and the Caribbean respectively[7]. On the other hand, while research conducted by Holland and Bruyère has not concluded an increase in the number of hurricanes in the North Atlantic, there has been an upward trend in the proportion of Category 4-5 hurricanes in the area[8].

This increase in natural disasters, and their intensity, can have a hard effect on those countries which have a reliance on agriculture. Agriculture as a percentage of GDP has been declining within the region in recent years due to policies of diversification of economies. However, in the countries of Honduras and Nicaragua the percentage share of agriculture is still slightly higher than 10%, while in Guatemala and Belize agriculture is slightly below 10% of GDP share[9]. Therefore, we can expect high levels of emigration from the agricultural sectors of these countries, heading toward higher elevations, such as the Central Plateau of Mexico, and the highlands of Guatemala. Furthermore, we can expect mass migration movements from Belize, which is projected to be partially submerged by 2100 due to rising sea levels[10].

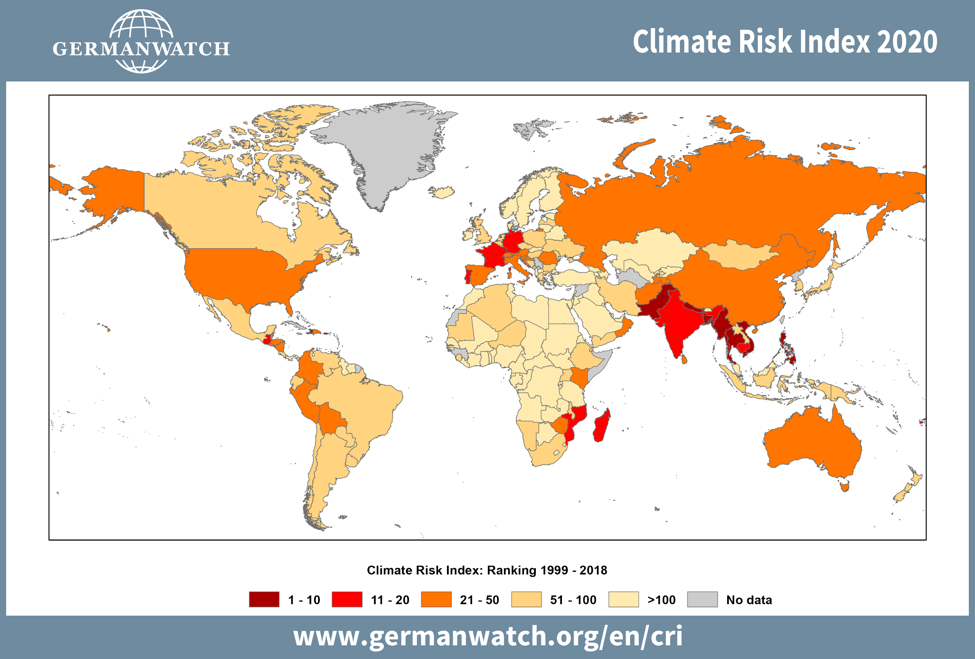

Figure 2 / Climate Risk Index 2020, from German Watch

Southeast Asia

The second region of concern is Southeast Asia, the region most affected by natural disasters, according to the research by Bello, mentioned previously. The countries of Southeast Asia are ranked in the top ten countries projected to be at most risk due to climate change, shown in Figure 2 above[11]. Southeast Asia is home to over 650 million people, about 8% of total world population, with 50% living in urban areas[12]. Recently, the OECD concluded that while the share in GDP of agriculture and fisheries has declined in recent years, there is still a heavy reliance on these sectors to push economy in the future[13]. In 2014, the Asian Development Bank carried out a study analyzing the possible cost of climate change on several countries in the region. It concluded that a possible loss of 1.8% in the GDP of six countries could occur by 2050[14]. These six countries had a high reliance on agriculture as part of the GDP, for example Bangladesh with around 20% of GDP and 48% of the workforce being dedicated to agricultural goods. Therefore, those countries with a high reliance on agricultural goods or fisheries as a proportion of GDP can be expected to be the sources of large climate migration in the future, more so than in the countries of Central America.

One possible factor is the vast river system within the area, which is susceptible to yearly flooding. With an increase in average water levels, we can expect this flooding to worsen gradually throughout the years. In the case of Bangladesh, 28% of the population lives on a coastline which sits below sea level[15]. With trends of submerged areas, Bangladesh is expected to lose 11% of its territory due to rising sea levels by 2050, affecting approximately 15 million inhabitants[16][17]. Scientists have reason to believe that warmer ocean temperatures will not only lead to rising sea levels, but also an intensification and increase of frequency in typhoons and monsoons[18], such as is the case with hurricanes in the North Atlantic.

Expected Destinations

Taking into account the analysis provided above, there are two possible migration movements: internal or external. In respect to internal migration, climate migrants will begin to move towards higher elevations and temperate climates to avoid the extreme weather that forced their exodus. The World Bank report, cited above, marked two locations within Central America that fulfill these criteria: the Central Plateau of Mexico, and the highlands of Guatemala. Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia, climate migrants will move inwards in an attempt to flee the rising waters, floods, and storms.

However, it is within reason to believe that there will be significant climate migration flows towards the USA and the People's Republic of China (PRC). Both the United States and China are global powers, and as such have a political stability and economic prowess that already attracts normal migration flows. For those fleeing the effects of climate change, this stability will become even more so attractive as a future home. For those in Southeast Asia, China becomes a very desired destination. With the second largest land area of any country, and with a large central zone far from coastal waters, China provides a territorial sound destination. As the hegemon in Asia, China could easily acclimate these climate migrants, sending them to regions that could use a larger agricultural workforce, if such a place exists within China.

In the case of Central America, the United States is already a sought-after destination for migrant movements, being the first migrant destination for all Central American countries except Nicaragua, whose citizens migrate in greater numbers to Costa Rica[19]. With the world's largest economy, and with the oldest democracy in the Western hemisphere, the United States is a stable destination for any refugee. In regard to relocation plans for areas affected by natural disasters, the United States also has shown it is capable of effectively moving at-risk populations, such as the Isle de Jean Charles resettlement program in the state of Louisiana[20].

Problems

While some would opine that 'climate migrants' and 'climate refugees' are interchangeable terms, they are unfortunately not. Under international law, there does not exist 'climate refugees'. The problem with 'climate refugees' is that there is currently no political will to change the definition of refugee to include this new category among them. In the case of the United States, section 101(42) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), the definition of a refugee follows that of the aforementioned 1951 Geneva convention[21], once again leaving out the supposed 'climate refugees'. The Trump administration has an interest in maintaining this status quo, especially in regard to its hard stance in stopping the flow of illegal immigrants coming from Central America. If a resolution should pass the United Nations Security Council, the Trump administration would have no choice but to change section 101(42) of the INA, thus risking an increased number of asylum applicants to the US. Therefore, it can confidently be projected that the current administration, and possibly future administrations, would utilize the veto power, given to permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, on such a resolution.

China, the strongest regional actor in Asia, does not have to worry about displeasing the voter. Rather, they would not allow a redefinition of refugee to pass the UN Security Council for reasons concerning the stability and homogeneity of the country. While China does accept refugees, according to the UNHCR, the number of refugees is fairly low, especially those from the Middle East. This is mostly likely due to the animosity that the Chinese government has for the Muslim population. In fact, the Chinese government has a tense relationship with organized religion in and of itself, but mostly with Islam and Buddhism. Therefore, it is very easy to believe that China would veto a redefinition of refugee to include 'climate refugees', in that that would open its borders to a larger number of asylum seekers from its neighboring countries. This is especially unlikely when said neighbors have a high concentration of Muslims and Buddhists: Bangladesh is 90% Muslim, and Burma (Myanmar) is 87% Buddhist[22]. Furthermore, both countries have known religious extremist groups that cause instability in civil society, a problem the Chinese government neither needs nor wants.

On the other hand, there is also the theory that the causes of climate migration simply cannot be measured. Natural disasters have always been a part of human history and have been a cause of migration since time immemorial. Therefore, how can we know if migrations are taking place due to climate factors, or due to other aggravating factors, such as political or economic instability? According to a report by the French think tank 'Population and Societies', when a natural disaster occurs, the consequences remain localized, and the people will migrate only temporarily, if they leave the affected zone at all[23]. This is due to the fact that usually that society will bind together, working with familial relations to surpass the event. The report also brings to light an important issue touched upon in the studies mentioned above: there are other factors that play in a migration due to a natural disaster. Véron and Golaz in their report cite that the migration caused by the Ethiopian drought of 1984 was also due in part to bad policies by the Ethiopian government, such as tax measures or non-farming policies.

The lack of diversification of the economies of these countries, and the reliance on agriculture could be such an aggravating factor. Agriculture is very susceptible to changes in climate patterns and are affected when these climate patterns become irregular. This can relate to a change of expected rainfall, whether it be delayed, not the quantity needed, or no rainfall at all. Concerning the rising sea levels and an increase in floods, the soil of agricultural areas can be contaminated with excess salt levels, which would remain even after the flooding recedes. For example, the Sula Valley in Honduras generates 62% of GDP, and about 68% of the exports, but with its rivers and proximity to the ocean, also suffers from occasional flooding. Likewise, Bangladesh's heavy reliance on agriculture, being below sea level, could see salt contamination in its soil in the near future, damaging agricultural property.

Reliance on agriculture alone does not answer why natural disasters could cause large emigration in the region. Bello and Professor Patricia Weiss Fagen[24] find that issues concerning the funding of local relief projects, corruption in local institutions, and general mismanagement of crisis response is another aggravating factor. Usually, forced migration flows finish with a return to the country or area of origin, once the crisis has been resolved. However, when the crisis has continuing effects, such as what happened in Chernobyl, for example, or when the crisis has not been correctly dealt with, this return flow does not occur. For example, in the countries composing the Northern Triangle, there are problems of organized crime which is already a factor for migration flows from the area[25]. Likewise, the failure of Bangladesh and Myanmar to deal with extremist Buddhist movements, or the specific case of the Rohinga Muslims, could inhibit return flows and even encourage leaving the region entirely.

Recommendations and Conclusions

The definition of refugee will not be changed or modified in order to protect climate migrants. That is a political decision by countries who sit at a privileged position of not having to worry about such a crisis occurring in their own countries, nor want to be burdened by those countries who will be affected. Facing this simple reality should help to find a better alternative solution, which is the continuing efforts of the development of nations, in order that they may be self-sufficient, for their sake and the population's sake. This fight does not have to be taken alone, but can be fought together through regional organizations who have a better understanding and grasp of the gravity of the situation, and can create holistic approaches to resolve and prevent these crises.

We should not expect the United Nations to resolve the problem of displacement due to natural disasters. The United Nations focuses on generalized and universal issues, such as that of global warming and climate change, but in my opinion is weak in resolving localized problems. Regional organizations are the correct forum to resolve this grave problem. For Central America, the Organization of American States (OAS) provides a stable forum where these countries may express their concerns with states of North and Latin America. With the re-election of Secretary General Luis Almagro, a strong and outspoken authority on issues concerning the protection of Human Rights, the OAS is the perfect forum to protect those displaced by natural disasters in the region. Furthermore, the OAS could work closely with the Inter-American Development Bank, which has the financial support of international actors who are not part of the OAS, such as Japan, Israel, Spain, and China, to establish the necessary political and structural reforms to better implement crisis management responses. This does not exclude the collusion with other international organizations, such as the UN. Interestingly, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has a project in the aforementioned Sula Valley to improve infrastructure to deal with the yearly floods[26].

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is another example of an apt regional organization to deal with the localized issues. Mostly dealing with economic issues, this forum of ten countries could carry out mutual programs in order to protect agricultural territory, or further integrate to allow a diversification of their economies to ease this reliance on agricultural goods. ASEAN could also call forth the ASEAN +3 mechanism, which incorporates China, Japan, and South Korea, to help with the management of these projects, or for financial aid. China should be interested in the latter option, seeing as it can increase its good image in the region, as well as protecting its interest of preventing possible migration flows to its territory. The Asian Development Bank, on the other hand, offers a good alternative financial source if the ASEAN countries so choose, in order to not have heavy reliance on one country or the other.

![Rice field terraces in Vietnam [Pixabay]. Rice field terraces in Vietnam [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/vietnam-blog.jpg)

▲ Rice field terraces in Vietnam [Pixabay].

COMMENT / Eduardo Arbizu

The combination of a market Economics and an authoritarian regime dominated by the Communist Party of Vietnam (VCP) has led Vietnam, a country of more than 90 million people, to become a key player in the future of Southeast Asia.

The current Vietnam is the consequence of a confusing and contradictory process of change that has transformed not only the country's Economics , but has also had a profound impact on social life, urban configuration, environment, domestic and foreign policies and whose final effects will be seen in the long term.

An impressive economic turnaround

The transformation of the economic model in Vietnam derives formally from the decision adopted at the sixth VCP congress in December 1986 to open the country to market Economics , but its roots lie earlier, in the economic crisis that followed the war, in the collapse of agricultural production that the radical implementation of a communist model provoked in 1979. This debacle forced to allow the private trade of any production surplus that exceeded the targets set by the State for enterprises or public lands. This sort of state capitalism paved the way for the liberalization that followed the death of the Stalinist leader, Le Duan, in 1986. The approval of the do-moi or renovation policy meant the withdrawal of planning and the option for the free market. It was not an ideological decision but an instrumental one. If the CP wanted to maintain control of the country, it needed to generate one million work a year, guarantee food for 90 million inhabitants and reduce poverty.

It has been an economic and social success: per capita income has increased dramatically and the population below the poverty line has been reduced from 60% to 20%. The US embargo ended in 1993 and in 1997 the two countries signed a new trade agreement . In 2007, Vietnam was admitted to the WTO. In this context of openness, more than 150,000 new enterprises were created under the new enterprise law and large international companies such as Clarks, Canon, Samsung and Intel set up production centers in Vietnam.

The achievements of the process, however, should not hide its weaknesses: an Economics controlled by the State through joint ventures and state-owned companies, a fragile rule of law, massive corruption, a network of families loyal to the PCV that accumulate wealth and own most of the private businesses, growing inequality and a deep ecological deterioration.