Breadcrumb

Blogs

![Minneapolis street crossing where George Floyd was stopped by local police [Fibonacci Blue]. Minneapolis street crossing where George Floyd was stopped by local police [Fibonacci Blue].](/documents/10174/16849987/george-floyd-blog.jpg)

▲ Minneapolis street crossing where George Floyd was stopped by local police [Fibonacci Blue].

COMMENTARY / Salvador Sánchez Tapia [Brigadier General (Res.)].

In a controversial public statement made on June 2, U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to deploy units of the Armed Forces to contain riots sparked by the death of African-American George Floyd at the hands of a police officer in Minnesota, and to maintain public order if they escalate in the level of violence.

Regardless of the seriousness of the event, and beyond the fact that the incident has been politicized and is being employee as a platform for expressing rejection of Trump's presidency, the possibility raised by the president poses an almost unprecedented challenge to civil-military relations in the United States.

For reasons rooted in its pre-independence past, the United States maintains a certain caution against the possibility that the Armed Forces can be employed domestically against citizens by whoever holds power. For this reason, when the Founding Fathers drafted the Constitution, while authorizing congress to organize and maintain armies, they explicitly limited their funding to a maximum of two years.

Against this background, and against the background of the tension between the Federation and the states, U.S. legislation has tried to limit the employment the Armed Forces in domestic tasks. Thus, since 1878, the Posse Comitatus limits the possibility of employing them in the fulfillment of missions for the maintenance of public order which it is the responsibility of the states to carry out with their own means, including the National Guard.

One of the exceptions to this rule is the Insurrection Act of 1807, invoked precisely by President Trump as an argument in favor of the legality of an eventual employment decision. This, despite the fact that this law has a restrictive spirit, since it requires the cooperation of the states in its application, and because it is designed for extreme cases in which they are unable, or unwilling, to maintain order, circumstances that do not seem applicable to the case at hand.

The controversial nature of the advertisement is attested to by the fact that voices as authoritative and so little inclined to publicly break its neutrality as that of Lieutenant General (ret.) James Mattis, Secretary of Defense of the Trump Administration until his premature relief in December 2018, or that of Lieutenant General (ret.) Martin Dempsey, head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Board between 2011 and 2015, have spoken out against this advertisement , thus joining the statements made by former presidents as diverse as George W. Bush and George W. Bush, who have spoken out against it. ) Martin Dempsey, head of the board Chiefs of Staff between 2011 and 2015, have spoken out against this employment, joining the statements made by former presidents as diverse as George W. Bush and Barak Obama, or those of the Secretary of Defense himself, Mark Esper, whose position against the possibility of using the Armed Forces in this status has recently been made clear.

The presidential advertisement has opened a crisis in the usually stable US civil-military relations (CMR). Beyond the scope of the United States, the question, of deep significance and affecting the core of CMR in a democratic state, is none other than whether or not to use the Armed Forces in public order or, in a broader sense, domestic tasks, and the risks associated with such a decision.

In the 1990s, Michael C. Desch, one of the leading authorities in the field of CMR, identified the correlation between the missions entrusted to the Armed Forces by a state and the quality of its civil-military relations, concluding that externally oriented military missions are the most conducive to healthy CMRs, while internal missions that are not purely military are likely to generate various pathologies in such relations.

In general, the existence of the Armed Forces in any state is primarily due to the need to protect it against any threat from outside. In order to carry out such a high task with guarantees, armies are equipped and trained for the lethal employment force, unlike police forces, which are equipped for a minimal and gradual use of force, which only becomes lethal in the most extreme, exceptional cases. In the first case, it is a matter of confronting an armed enemy that is trying to destroy one's own forces. In the second, force is used to confront citizens who may, in some cases, use violence, but who remain, after all, compatriots.

When military forces are employed in tasks of this nature, there is always a risk that they will produce a response in accordance with their training, which may be excessive in a law and order scenario. The consequences, in such a case, can be very negative. In the worst case scenario, and above all other considerations, the employment may result in a perhaps avoidable loss of life. Moreover, from the point of view of CMR, the soldiers that the nation submission for its external defense could become, in the eyes of the citizenry, the enemies of those they are supposed to defend.

The damage this can produce for civil-military relations, for national defense and for the quality of a state's democracy is difficult to measure, but it can be intuited if one considers that, in a democratic system, the Armed Forces cannot live without the support of their fellow citizens, who see them as a beneficial force for the nation and to whose members they extend their recognition as its loyal and disinterested servants.

Abuse in the employment the Armed Forces in domestic tasks may, in addition, deteriorate their already complex preparation, weakening them for the execution of the missions for which they were conceived. It may also end up conditioning their organization and equipment to the detriment, once again, of their essential tasks.

On the other hand, and although today we are far away and safe from such a scenario, this employment may gradually lead to a progressive expansion of the tasks of the Armed Forces, which would extend their control over purely civilian activities, and which would see their range of tasks increasingly broadened, displacing other agencies in their execution, which could, undesirably, atrophy.

In such a scenario, the military institution could cease to be perceived as a disinterested actor and come to be seen as another competitor with particular interests, and with a control capacity that it could use for its own benefit, even if this were opposed to the nation's interest. Such a status, in time, would lead hand in hand to the politicization of the Armed Forces, from which would follow another damage to the CMR that would be difficult to quantify.

Decisions such as the one targeted by President Trump may ultimately place members of the Armed Forces in the grave moral dilemma of using force against their fellow citizens, or disobeying the President's orders. Because of its gravity, therefore, the decision to commit the Armed Forces to such tasks should be made on an exceptional basis and after careful consideration.

It is difficult to determine whether the advertisement made by President Trump was just a product of his temperament or whether, on the contrary, it contained a real intention to use the Armed Forces in the disturbances that are dotting the country, in a decision that has not occurred since 1992. In any case, the president, and those advising him, must assess the damage that can be inferred from it for civil-military relations and, therefore, for the American democratic system. This without forgetting, moreover, the responsibility that falls on America's shoulders in the face of the reality that a part of humanity looks to the country as a reference letter and a model to imitate.

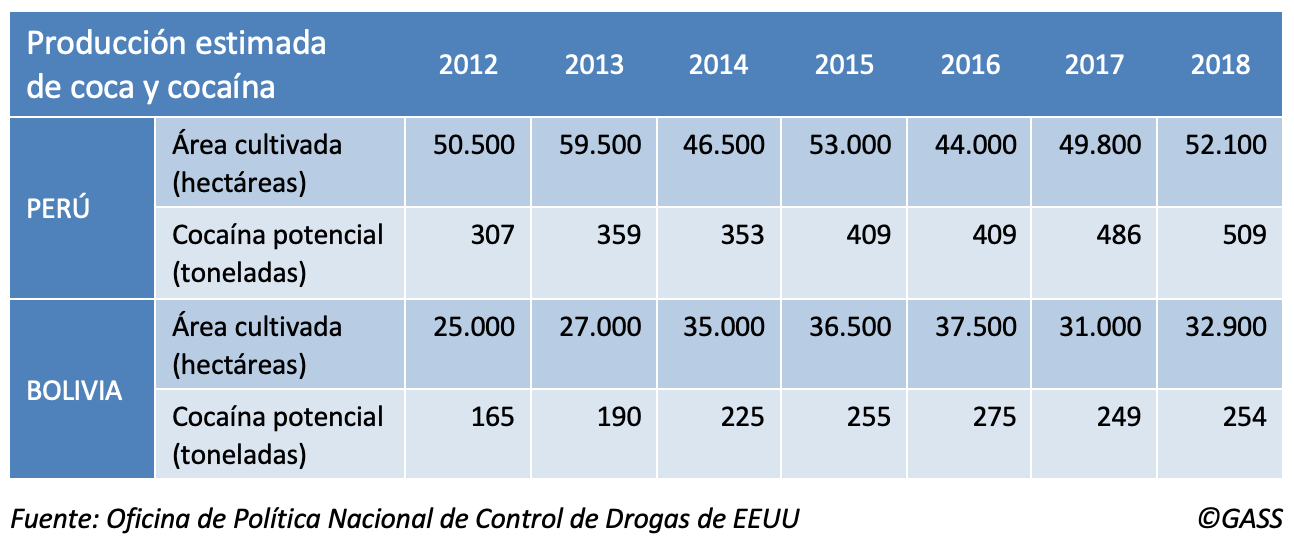

Bolivia has consolidated its role in distributing Peruvian cocaine and its own cocaine for consumption in South America and export to Europe.

-

In 2019, the government of Martin Vizcarra eradicated 25,526 hectares of coca cultivation, half of the estimated total extension of plantations.

-

Peru had a record potential cocaine production of 509 tons in 2018; Bolivia's was 254, one of the historically highest, according to US

-

The US accused Morales towards the end of his term of office of having "manifestly failed" to fulfill his international obligations with his 2016-2020 counter-narcotics plan.

▲ Coca eradication operation in Alto Huallaga, Peruproject CORAH].

report SRA 2020 / Eduardo Villa Corta [PDF version] [PDF version].

MAY 2020-Since Peru's national plans against coca cultivation began in the 1980s, eradication campaigns have never reached what is known as the VRAEM (Valley of the Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro Rivers), a difficult-to-access area in the center of the southern half of the country. Organized crime operates in this area, especially the remnants of the old Shining Path guerrillas, now dedicated to drug trafficking and other illicit businesses. The area is the source of 64% of the country's potential cocaine production. Peru is the second largest producer in the world, after Colombia.

The government of President Martin Vizcarra carried out in 2019 a determined policy of suppression of illicit crops. The eradication planproject Especial de Control y Reducción del Cultivo de Coca en el Alto Huallaga or CORAH) was applied last year to 25,526 hectares of coca crops (half of the existing ones), of which 750 would have corresponded to the VRAEM (operations took place in the areas of Satipo, Tambo River and Alto Anapati, in the Junín region).

These actions should translate, when the figures for 2019 are presented, into a reduction in total coca cultivation and potential cocaine production, thus breaking the increase experienced in recent years. According to the latest International Narcotics Control Strategyreport (INCSR) of the US State department , which closely follows this illicit activity in the countries of the region, in 2018 there were 52,100 hectares of coca in Peru (compared to 44,000 in 2016 and 49,800 in 2017), whose extension and quality of cultivation could generate a record production of 509 tons of cocaine (compared to 409 in 2016 and 486 in 2017). Although in 2013 there was a larger cultivated area (59,500 hectares), then the cocaine potential stood at 359 tons.

From Peru to Bolivia

This increase in recent years in the generation of cocaine in Peru has consolidated Bolivia's role in the trafficking of that drug, since in addition to being the third largest producer country in the world (in 2018 there were 32,900 hectares cultivated, with a potential production of 254 tons of narcotic substance, according to the US), it is a transit zone for cocaine of Peruvian origin.

The fact that only about 6% of the cocaine reaching the United States comes from Peru (the rest comes from Colombia), indicates that most of the Peruvian production goes to the growing market in Brazil and Argentina and to Europe, and therefore its natural exit point is through Bolivia. Thus, Bolivia is considered a major "distributor".

Some of the drugs arrive in paste form and are refined in Bolivian laboratories. The goods are smuggled into Bolivia using small planes, which sometimes fly at less than 15 meters above the ground and drop the cocaine packages in uninhabited rural areas; they are then picked up by elements of the organization. The movement is also carried out by road, with the drugs camouflaged on cargo roads, and to a lesser extent using Lake Titicaca and other waterways connecting the two countries.

Once across the border, the drugs from Peru, along with those produced in Bolivia, travel to Argentina and Chile, especially through the Bolivian city of Santa Cruz and the Chilean border crossing of Colchane, or enter Brazil -- directly or through Paraguay, using for example the crossing between the Paraguayan town of Pedro Juan Caballero and the Brazilian town of Ponta Pora -- for consumption in South America's largest country, whose Issue has climbed to second place in the world, or to reach international ports such as Santos. This port, which is Sao Paulo's outlet to the sea, has become the new hub of the global narcotics trade, from which almost 80% of Latin America's drugs leave for Europe (sometimes via Africa).

Production in Bolivia has been growing again since the middle of the last decade, although in the Bolivian case there is a notorious difference between the often divergent figures offered by the United States and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Both estimates agree that there was a previous decline, attributed by the La Paz government to the so-called "rationalization of coca production", which reduced production by 35% and adjusted cultivation areas to those permitted by law, in a country where traditional uses of coca are allowed.

However, the Coca Law promoted in 2017 by President Evo Morales (his political degree program originated in the coca growers' unions, whose interests he later continued to defend) protected an extension of production, raising the permitted hectares from 12,000 to 22,000. The new law covered an increase that was already occurring and encouraged greater excesses that have far exceeded the Issue required for traditional uses, which programs of study by the European Union put at less than 14,700 hectares. In fact, the UNODC estimated in its 2019 report that between 27% and 42% of the coca leaf grown in 2018 was not sold in the only two local markets authorized for it, indicating that at least the rest was destined for cocaine production.

For 2018, the UNODC determined a production of 23,100 hectares, in any case above what is allowed by law. US data speak of 32,900 hectares, which was an increase of 6% over the previous year, and a potential cocaine production of 254 tons (up 2%).

Sixty-five percent of Bolivian production takes place in the Yungas area, near La Paz, and the remaining 35% in Chapare, near Cochabamba. In the latter area, crops are expanding, encroaching on the Tipnis natural reservation . The park, which goes deep into the Amazon, suffered in 2019 important fires: intentional or not, the annihilated tropical vegetation could give way to clandestine coca plantations.

After Morales

The 2020 US State department report highlights the increased anti-drug commitment of the Bolivian authorities who in November 2019 succeeded the Morales government, which had maintained "inadequate controls" over coca cultivation. The US considers that Morales' 2016-2020 anti-drug plan "prioritized" actions against criminal organizations rather than combating coca growers' production that exceeded the permitted Issue . Shortly before leaving office in September, Morales was singled out by the US for having "manifestly failed" to comply with international obligations subject drug control.

According to the US, the transitional government "has made important strides in drug interdiction and extradition of drug traffickers". This increased control by the new Bolivian authorities, together with the determined action of the Vizcarra government in Peru, should lead to a reduction in coca cultivation and cocaine production in both countries, and therefore in its export.

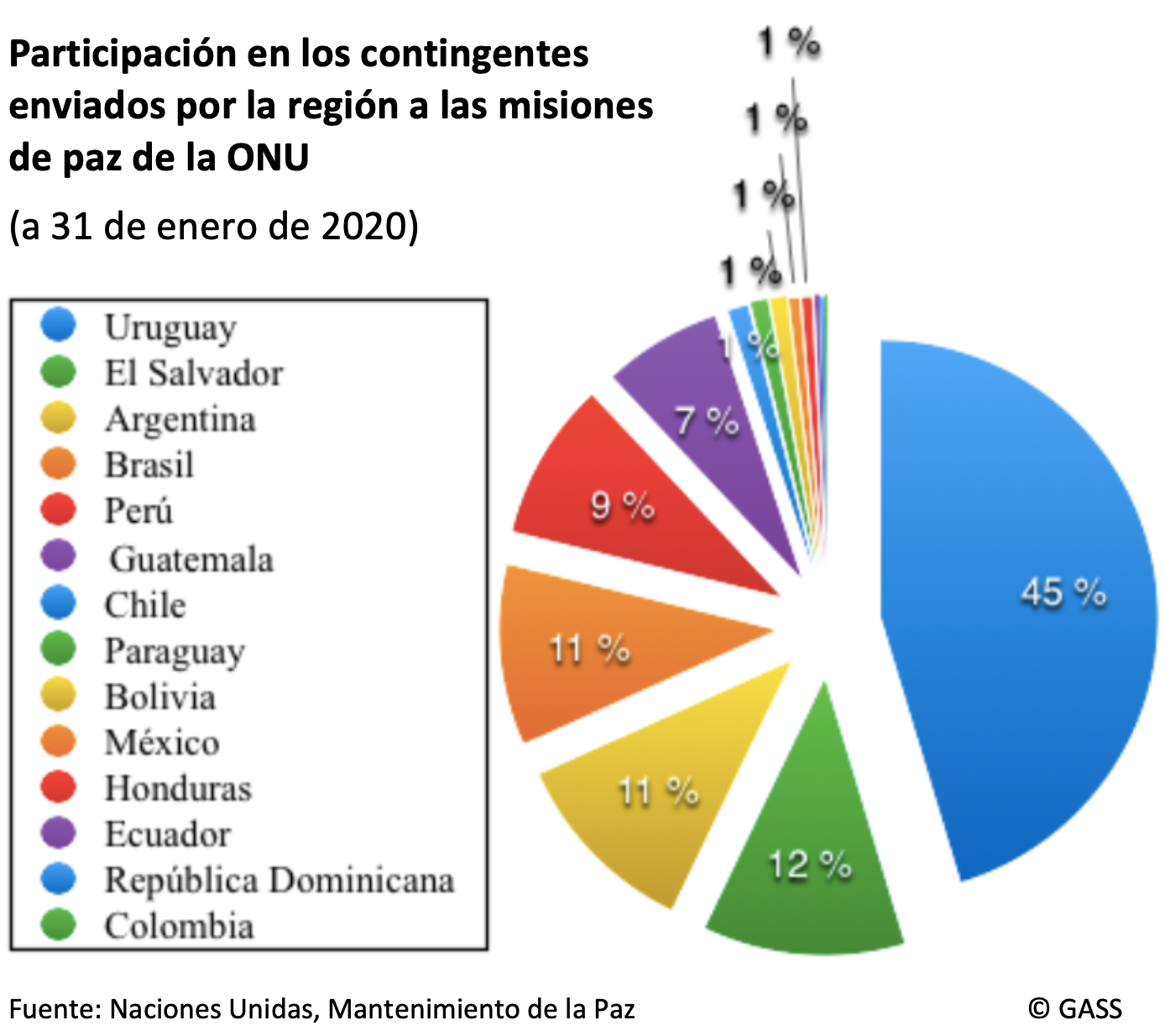

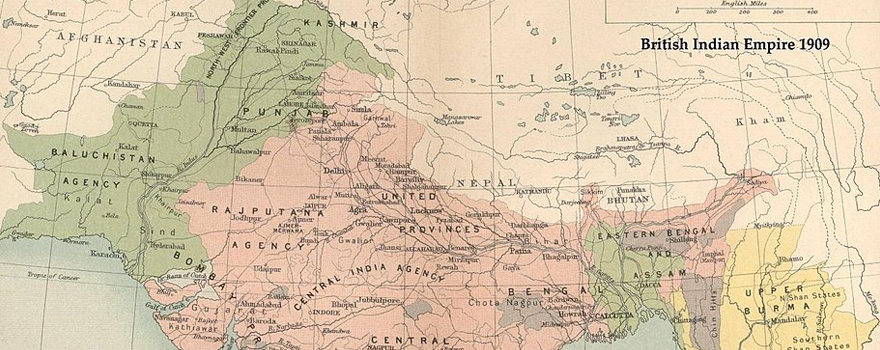

Uruguay contributes 45.5% of the Latin American workforce and El Salvador is second with 12%, both ahead of the regional powers.

-

Of the total 82,480 troops in the fourteen UN peacekeeping missions at the beginning of 2020, 2,473 came from Latin American countries, most of them military and police.

-

Nearly all troops from the region serve in missions in Africa; 45.4% serve in the DRC stabilization plan.

-

After Uruguay and then El Salvador come Argentina, Brazil, Peru and Guatemala; Mexico, on the other hand, is one of the lowest contributors (only 13 experts and employees, not troops).

![Bolivian soldier in training exercises for UN peacekeeping missions, 2002 [Wikipedia]. Bolivian soldier in training exercises for UN peacekeeping missions, 2002 [Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/cascos-azules-blog.jpg)

▲ Bolivian soldier in training exercises for UN peacekeeping missions, 2002 [Wikipedia].

report SRA 2020 / Jaime Azpiri[PDF version].

MAY 2020-Latin America's contribution to international peacekeeping missions sponsored by the United Nations is below the weight of its population and Economics in the world (around 8% and 7%, respectively). Of the total of 82,480 people participating in the various UN missions as of January 31, 2020, only 2,473 were from Latin American countries, representing 2.9% of the total. A similar percentage (3%) was recorded when considering only the military or police staff of the missions (about 2,150 uniformed personnel, out of a total of 70,738; the rest corresponded to employees and experts).

This is a smaller external presence than might be expected, given the insistence of many countries in the region on multilateralism and the desirability of strong international institutions to limit the expansionary impulses of the great powers. A special exception is Uruguay, precisely the most coherent nation in its defense of international arbitration, which, despite its small population, is by far the largest contributor of staff to peacekeeping missions. Its 1,125 envoys make up 45.5% of the total Latin American contingent.

While Uruguay's strong contribution is not surprising, it is surprising that the second country with the highest participation is El Salvador, with 293 people (12% of Latin America's contribution). This is followed by two very important countries, Argentina and Brazil, (272 and 252 envoys, respectively); then Peru (231) and Guatemala (176). On the other hand, Mexico, despite all its economic and human potential, is particularly absent from these international missions (only 13 people, moreover as employees or experts, not troops), both due to constitutional restrictions and political doctrine. In the case of Colombia (only 2 experts), this may be due to the need to devote its military force entirely to the pacification of the country itself, although one would expect greater capacity and availability from a NATO global partner , the only designation in Latin America that it achieved in 2018.

The most attended international assignment, which brings together 45.4% of the total contingent in the region, is that of the UN mission statement for the stabilization of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, from whose name in French comes the acronym MONUSCO. It involves 1,123 Latin Americans, the majority of whom are Uruguayan envoys (934), with the greatest participation also of Guatemalans on military missions abroad (153).

Previous outstanding missions

Although Latin American countries generally do not participate much in military missions abroad, the sending of troops abroad is not alien to the history of the American republics after their independence. A first intervention was the so-called "ABC", a coalition formed by Argentina, Brazil and Chile in the context of the Mexican Revolution, at the beginning of the last century, to prevent civil war in the North American country. Another conflict that required mediation was the Chaco War in the 1930s. In this confrontation between Paraguay and Bolivia, the interventions of Chile and Argentina were crucial to subsequently define the reaffirmation of the nationality of the Chaco region.

At the end of the 20th century, the most important mission statement was the one aimed at pacifying the former Yugoslav republics, called UNPROFOR by the UN. Argentina was the Latin American country with the largest presence of troops in that scenario. Shortly afterwards, in the 1990s, two international missions were implemented, this time in the Western Hemisphere itself, to secure the agreements that put an end to the civil wars in El Salvador (ONUSAL) and Guatemala (MINUGUA). At the end of that decade, the MOMEP was articulated to impose an armistice between Peru and Ecuador, which were at war in the Cenepa War.

Also in Colombia, some leaders at some point considered the possibility of apply for the presence of blue helmets in order to control and, in the long term, put an end to the FARC insurrection. Later Colombian President Álvaro Uribe proposed in 1998 the presence of international troops in the face of the inability of the government of the time to control the situation, but the initiative was not carried out. After the peace agreement in 2016, the signatory parties asked the UN for a mission statement to monitor compliance with the terms of the agreement, known as UNVMC, which operates with a maximum of 120 people (some civilians and a hundred military and police), of which, in January 2020, 94 came from Latin American countries.

The contrast between Uruguay and Mexico

Today, the countries of the region are present in 14 different peace missions (out of the total of 21 promoted by the UN), especially in Africa but also in other parts of the world. In MINUSCA, convened for the pacification of the Central American Republic, 9 Latin American nations participate, the same issue as in UNVMC, the mission statement of verification of the peace agreements in Colombia. In UNMISS, mission statement of attendance in South Sudan, 8 countries participate and in MONUSCO, implemented in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 7 do so.

As mentioned above, Uruguay is the largest contributor to the missions underway (1,126 personnel, as of January 31). This staff is basically assigned to MONUSCO (934) and to a lesser extent to UNDOF (170), which ensures security in the Golan Heights as a separation force between Syrians and Israelis; in total, Uruguayan blue helmets are present in 6 different missions. This service has been especially recognized by the United Nations, which values Uruguay's long trajectory in this subject: for example, it highlighted its attendance in the mission statement carried out in Haiti after the disaster caused by hurricane Dean, to which it assigned 13,000 troops between 2007 and 2014. The contribution of Uruguay, a country of only 3.5 million inhabitants, is greater than that of Spain (648), France (732) or Italy (1084).

On the other hand, the case of Mexico is the most striking because of its very limited participation in peacekeeping missions, considering that it is one of the powers in the region. The North American country is the second Latin American nation that uses the most resources for the development its Armed Forces, with a total of 7 million dollars, placing it, by far, behind the first place that corresponds to Brazil, with a total of almost 29.5 million dollars. Historically, Mexico has participated in more than 80 peacekeeping missions, providing troops from the Federal Police and the Army, generally in low issue. The previous president, Enrique Peña Nieto, announced in 2014 that Mexican units would once again participate decisively in armed operations in support of the UN, however today their contribution is reduced to 13 people (9 experts and 4 employees), which represents only 1% of Latin American participation. The most relevant reason to explain the Mexican phenomenon is the long tradition in favor of the Estrada doctrine of non-intervention in the internal affairs of other countries. In addition, the Mexican Constitution restricts the deployment of troops abroad unless Mexico has declared war on an enemy.

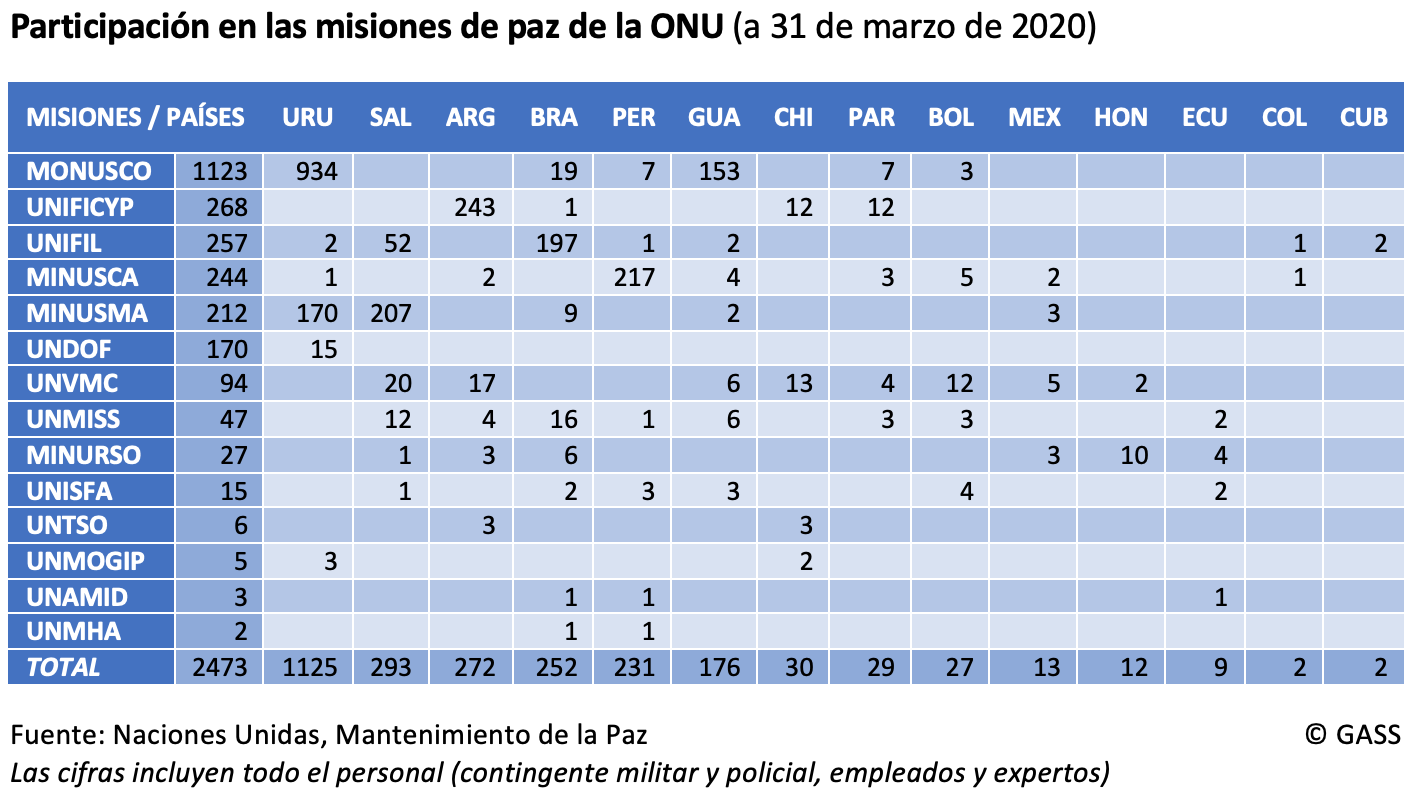

▲ The British Raj in 1909 showing Muslim majority areas in green

ESSAY / Victoria Paternina and Claudia Plasencia

Pakistan's partition from India in 1947 marked the beginning of a long road of various territorial disputes, causing different effects in the region. The geopolitics of Pakistan with India are often linked when considering their shared history; and in fact, it makes sense if we take the perspective of Kashmir as the prominent issue that Islamabad has to deal with. However, neither the history nor the present of Pakistan can be reduced to New Delhi and their common regional conflict over the Line of Control that divides Kashmir.

The turbulent and mistrustful relations between India and Pakistan go beyond Kashmir, with the region of Punjab divided in two sides and no common ground between New Delhi and Islamabad. In the same way, the bitter ties between Islamabad and a third country are not exclusively with India. Once part of Pakistan, Bangladesh has a deeply rooted hatred relationship with Islamabad since their split in 1971. Looking beyond Kashmir, Punjab and Bangladesh show a distinct aspect of the territorial disputes of the past and present-day Pakistan. Islamabad has a say in these issues that seem to go unnoticed due to the fact that they stand in the shadow of Kashmir.

This essay tries to shed light on other events that have a solid weight on Pakistan's geopolitics as well as to make clear that the country is worthy of attention not only from New Delhi's perspective but also from their own Pakistani view. In that way, this paper is divided in two different topics that we believe are important in order to understand Pakistan and its role in the region. Punjab and Bangladesh: the two shoved under the rug by Kashmir.

Punjab

The tale of territorial disputes is rooted deeply in Pakistan and Indian relations; the common mistake is to believe that New Delhi and Islamabad only fight over Kashmir. If the longstanding dispute over Kashmir has raised the independence claims of its citizens, Punjab is not far from that. On the edge of the partition, Punjab was another region in which territorial lines were difficult to apply. They finally decided to divide the territory in two sides; the western for Pakistan and the eastern for India. However, this issue automatically brought problems since the majority of Punjabis were neither Hindus nor Muslims but rather Sikhs. Currently, the division of Punjab is still in force. Despite the situation in Pakistan Punjab remains calm due to the lack of Sikhs as most of them left the territory or died in the partition. The context in India Punjab is completely different as riots and violence are common in the eastern side due to the wide majority of Sikhs that find no common ground with Hindus and believe that India has occupied its territory. Independence claims have been strengthened throughout the years on many occasions, supported by the Pakistani ISI in order to destabilize India. Furthermore, the rise of the nationalist Indian movement is worsening the situation for Punjabis who are realizing how their rights are getting marginalized in the eyes of Modi's government.

Nonetheless, the question of Punjabi independence is only a matter of the Indian side. The Pakistan-held Punjab is a crucial province of the country in which the wide majority are Muslims. The separation of Punjab from Islamabad would not be conceived since it would be devastating. For Pakistan, it would mean the loss of 72 million inhabitants; damaging the union and stability of the country. All of this taking into account that Punjab represents a strong pillar for the national economy since it is the place where the Indus river - one of the most important ones - flows. It can be said that there is no room for independence of the Pakistani side, nor for a rapprochement between both parts of the former Punjab region. They have lost their main community ties. Besides, the disagreements are between New Delhi and Eastern Punjab, so Islamabad has nothing to do here. According to that, the only likely long-term possibility would be the independence of the Indian side of the Punjab due to the growth of the hatred against New Delhi. Additionally, there are many Sikhs living abroad in UK or Canada who support the independence of Punjab into a new country "Khalistan" strengthening the movement into an international concern. Nevertheless, the achievement of this point would probably increase the violence in Punjab, and in case they would become independent it would be at the expense of many deaths.

There is a last point that must be taken into account when referring to India-Pakistan turbulent territorial relations. This is the case of the longstanding conflict over water resources in which both countries have been increasing tensions periodically. Considering that there is a scarcity of water resources and a high demand of that public good, it is easy to realize that two enemies that share those resources are going to fight for them. Furthermore, if they both are mainly agrarian countries, the interest of the water would be even harder as it is the case of Pakistan and India. However, for more than five decades both Islamabad and New Delhi have maintained the Indus Waters Treaty that regulates the consumption of the common waters. It divides the six rivers that flow over Pakistan and India in two sides. The three western ones for Pakistan, and the other three of the eastern part for India. Nevertheless, it does not mean that India could not make any use of the Pakistani ones or vice versa; they are allowed to use them in non-consumptive terms such as irrigation, but not for storage or building infrastructures[1]. This is where the problem is. India is seemed to have violated those terms by constructing a dam in the area of the Pakistani Indus river in order to use the water as a diplomatic weapon against Islamabad.

This term has been used as an Indian strategy to condemn the violence of Pakistan-based groups against India undermining in that way the economy of Pakistan which is highly dependent on water resources. Nevertheless, it is hard to think that New Delhi would violate one of the milestones treaties in its bilateral relations with Pakistan. Firstly, because it could escalate their already existent tensions with Pakistan that would transform into an increase of the violence against India. Islamabad's reaction would not be friendly, and although terrorist activities follow political causes, any excuse is valid to lead to an attack. Secondly, because it would bring a bad international image for PM Modi as the UN and other countries would condemn New Delhi of having breached a treaty as well as leaving thousands of people without access to water. Thirdly, they should consider that rivers are originated in the Tibet, China, and a bad movement would mean a reaction from Beijing diverting the water towards Pakistan[2]. Finally, India does not have enough infrastructure to use the additional water available. It is better for both New Delhi and Islamabad to maintain the issue over water resources under a formal treaty considering their mutual mistrust and common clashes. Nevertheless, it would be better for them to renew the Indus Waters Treaty in order to include new aspects that were not foreseen when it was drafted as well as to preserve the economic security of both countries.

Bangladesh

Punjab is a territory obligated to be divided in two between India and Pakistan, yet Bangladesh separated itself completely from Pakistan and finds itself in the middle of India. Bangladesh, once part of Pakistan, after a tumultuous war, separated into its own country. While India did not explicitly intervene with Bangladesh and Pakistan's split, it did promote the hatred between the two for its own diary and to increase in power. The scarring aspect of the split of Bangladesh from Pakistan is the bloody war and genocide that took place, something that the Bengali people still have not overcome to this day. The people of Bangladesh are seeking an apology from Pakistan, something that does not look like it is going to come anytime soon.

Pakistan and Bangladesh share a bitter past with one another as prior to 1971, they were one country which separated into two as a result of a bloody war and emerging political differences. Since 1971 up to today, India and the Awami league have worked to maintain this hatred between Bangladesh and Pakistan through propagandist programs and different techniques. For example, they set up a war museum, documentaries and films in order to boast more the self-proclamation of superiority on behalf of India against Bangladesh and Pakistan. India and the Awami League ignore the fact that they have committed atrocities against the Bengali people and that in large part they are responsible for the breakup between Pakistan and Bangladesh. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) worked to improve relations with Pakistan under the governments of Ziaur Rahman, Begum Khaldia Zia, and Hossain Mohammad Ershad in Bangladesh, who had maintained distance from India. Five Pakistani heads of government have visited Bangladesh since 1980, along with signing trade and cultural agreements to improve relations between the two nations.[3] While an alliance between Pakistan and Bangladesh against India is not a realistic scenario, what is important for Pakistan and Bangladesh for the next decade to come is attempt to put their past behind them in order to steer clear of India and develop mutually beneficial relations to help improve their economies. For example, a possible scenario for improving Pakistan and Bangladesh relations could be to join the CPEC to better take advantage of the trade opportunities offered within South Asia, West Asia, Central Asia, and China and Russia.[4] The CPEC will be a key player in this process.

Despite decades of improving trade and military links, especially as a defense against Indian supremacy in the region, the two countries continue to be divided by the question of genocide. Bangladesh wants Pakistan to recognize the genocide and its atrocities and teach them as a part of its history. However, Pakistan has refused to do so and has even referred to militant leader executed for war crimes as being killed for his loyalty to Pakistan.[5] Bangladesh is a country with a long history of genocide.

Even though India supported Bangladesh in its independence from Pakistan, Bangladesh thinks that India is self-serving and that they change ideas depending on their own convenience.[6] An alliance of Pakistan and Bangladesh, even though it is against a common enemy, India, is not realistic given the information recently provided. India is a country that yes, even though they helped Bangladesh against Pakistan, they are always going to look out for themselves, especially in search to be the central power in the region. India sees still a lot of potential for their power in the coming decades. Indian PM Narendra Modi is very keen on making strategic choices for the country to transform and increase its global leadership position.[7] India's strategy for the next few years has been to make the right choices for the future.

The hostile relations between Pakistan and India find their peak in its longstanding conflict over Kashmir, but Punjab and Bangladesh must not be put in the shadow. The further directions of both PM Imran Khan and PM Modi could have consequences that would alter the interests of Punjab and Bangladesh as different actors in the international order. In the case of Punjab their mutual feelings of mistrust could challenge the instability of a region far from being calm. It is true that independence claims is not an issue for Pakistan itself since both Islamabad and Pakistan-held Punjab would lose in that scenario, and they both know it. Nonetheless, Indian Punjabis' reality is different. They have crucial problems within New Delhi, again as a historical matter of identity and ethnicity that is still present nowadays. Sikhs have not found common ground with Hindus yet and it does not seem that it will happen in a near future. In fact, tensions are increasing, posing a threat for two nations with their views on Kashmir rather than on Punjab. In the case of Bangladesh, its relations with Pakistan did not have a great start. Bangladesh gained freedom with help from India and remained under its influence. Both Pakistan and Bangladesh took a long time to adjust to the shock of separation and their new reality, with India in between them.

In conclusion, Punjab and Bangladesh tend to be the less important territorial issues, and not a priority neither for Islamabad nor for New Delhi that are more engaged in Kashmir. However, considering the magnitude of both disputes, we should appreciate how the Sikhs in the Indian-held territory of Punjab as well as the Bengali people deserve the same rights as the Kashmiris to be heard and to have these territorial disputes settled once and for all.

BIBLIOGRAPHY .

Ayres, Alyssa. "India: a 'Major Power' Still below Its Potential." Lowy Institute, July 24, 2018.

Iftikhar, Momin. "Pakistan-Bangladesh Relations." The Nation. The Nation, December 15, 2018.

"Indus Water Treaty: Everything You Need to Know". ClearIAS.

Muhammad Hanif, Col. "Keeping India out of Pakistan-Bangladesh Relations." Daily Times, March 6, 2018.

Sami, Shafi. "Pakistan Bangladesh Relations In the Changing International Environment." JSTOR. Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, 2017.

Shakoor, Farzana. "Pakistan Bangladesh Relations Survey." JSTOR. Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, 2017.

[1] "Indus Water Treaty: Everything You Need to Know". Clearias. Accessed March 24.

[2] ibid

[3] Muhammad Hanif, Col. "Keeping India out of Pakistan-Bangladesh Relations." Daily Times, March 6, 2018.

[4] Iftikhar, Momin. "Pakistan-Bangladesh Relations." The Nation. The Nation, December 15, 2018.

[5] Sami, Shafi. "Pakistan Bangladesh Relations In the Changing International Environment." JSTOR. Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, 2017.

[6] Shakoor, Farzana. "Pakistan Bangladesh Relations Survey." JSTOR. Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, 2017.

[7]Ayres, Alyssa. "India: a 'Major Power' Still below Its Potential." Lowy Institute, July 24, 2018.

From the success of super-minister Sérgio Moro to the failure of 'hugs, not bullets': two different signs in the first year of populist presidents in Brazil and Mexico

-

AMLO promised to end the continuous annual rise in homicides registered in the terms of his two predecessors, but throughout 2019 he accentuated it

-

Improved figures in Brazil are overshadowed by an increase in accidental deaths in police operations and in the issue of temporary inmates in prisons

-

In the first months of 2020 in both Mexico and Brazil homicides have increased, but confinement by Covid-19 could affect annual statistics

![Mexican president at the launch of the National Guard in June 2019 [Gov. of Mexico]. Mexican president at the launch of the National Guard in June 2019 [Gov. of Mexico].](/documents/10174/16849987/homicidios-brasil-mexico-blog.jpg)

▲ The Mexican president at the launch of the National Guard in June 2019 [Gov. of Mexico].

report SRA 2020 / Túlio Dias de Assis and Marcelina Kropiwnicka[PDF version].

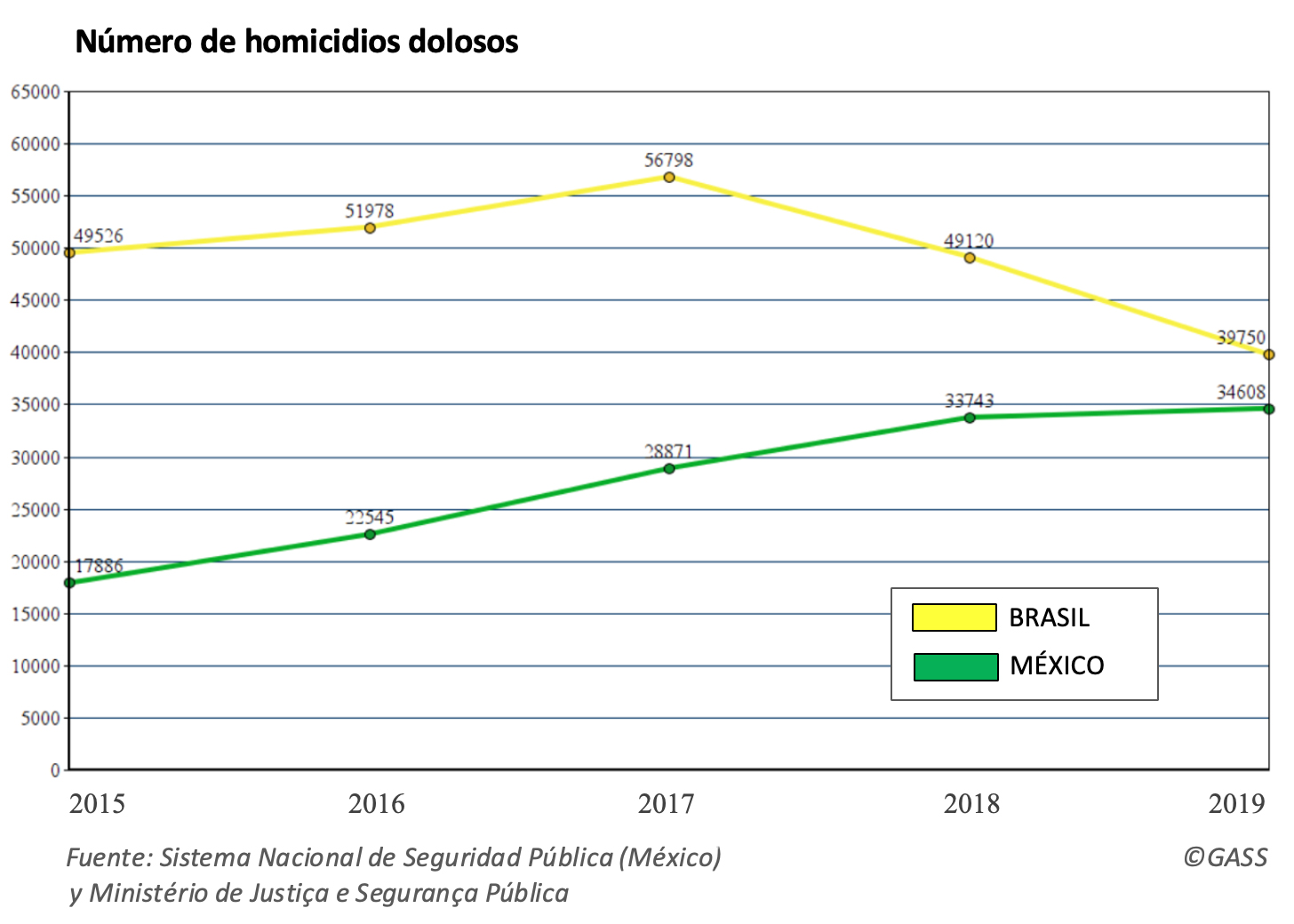

MAY 2020-One of Latin America's best-known conflicts is its high level of violence, often as a consequence of the strong presence of organized crime. Within this regional paradigm, not all leaders face the problem of crime in the same way. While some opt for a more passive policy, others prefer to bet on the iron fist, despite the risks it may entail. 2019 was the first year in office of Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Jair Bolsonaro, populist leaders of opposing ideologies, who came to power barely a month apart. In Brazil homicides went down, in Mexico they went up.

Mexico

Throughout 2019 there were a total of 35,588 victims of intentional homicide in Mexico. This means that, as 2019 came to an end, an all-time high in homicides at the national level was left behind. In doing so, President López Obrador, known by the abbreviation AMLO, failed to fulfill his electoral promise to reduce violence. Although he maintained his approval rating at 72% at the end of 2019, his acceptance has been damaged in the aftermath by his management of the coronavirus health crisis.

Three previous administrations had favored military combat against drug cartels, but López Obrador established a divergent security strategy upon his arrival, focusing more on the self-described "abrazos, no balazos" (hugs, not bullets) approach . This approach led to the release of Ovidio Guzmán, son of Joaquín 'El Chapo' Guzmán, which the government argued was motivated by a desire to avoid an escalation of cartel violence. In addition, AMLO created the National Guard, a new security force that has been deploying tens of thousands of troops, formerly from the Army and Federal Police, to tackle organized crime in core topic areas across the country. While the new strategy aims to strengthen security and tackle violence in the cities, it has so far failed to curb barbarism. The president has even reneged on another promise and announced that for the time being the army will remain on the streets sharing the role of citizen security.

The issue of intentional homicides in 2019 was 34,582, up 2.5% from 33,743 the previous year; femicides reached 1,006, up 10.3% from 912 in 2018, according to the National Public Security System (SNSP). Although in previous years, during the term of Presidents Enrique Peña Nieto, there were greater increases - the previous increases were 15.7% (from 2017 to 2018), 26.5% (from 2016 to 2017) and 25.1% (from 2015 to 2016) - the 2019 homicides represent the highest overall figure recorded in the last two decades. The figures of Felipe Calderón's (PAN) term, the first to take the Army to the streets to fight drug trafficking, were surpassed in Peña Nieto's (PRI) term and now there has been an increase again in the first year of López Obrador (Morena). All three criticized the security management of their predecessors and all three failed in their purpose (AMLO at least for the moment).

On average, 2,881 murders were committed per month in 2019; the highest issue recorded was 2,993 murders in June and the lowest issue was 2,731 in April. The state with the most homicides was Guanajuato, followed by the state of Mexico and leave California. In terms of homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants, Colima ranked first, with 98.3, followed by leave California (80.6) and Chihuahua (68.7).

Much of the violence that has occurred across the country is directly related to gang formations and drug traffickers, and the struggle for dominance of local markets. It is therefore not surprising that Colima, home to the strategic port of Manzanillo, a hotbed of illicit activities, is the state at the top of the blacklist. In addition, there is a partnership between criminal groups on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border for the mutual supply of drugs and weapons. Seventy percent of homicides are committed with firearms, many of which have been smuggled across the border. The status not only undermines security in Mexico but also in the United States.

Donald Trump has urged Mexico to "wage war" against the cartels. In November he announced he was officially labeling them as terrorist organizations. "The United States is ready, willing and able to engage and do the work quickly and effectively," Trump tweeted at the time. However, he ended up postponing that proclamation at the request of the Mexican president.

In the first quarter of 2020, homicides continued their upward trend, with 269 homicides more than in the same quarter of the previous year. While the social distancing measures adopted during the Covid-19 crisis may change the trend in the second semester, the lower investment in security to direct public expense towards the health and economic sectors may push up the issue of murders.

Brazil

In contrast to Mexico, Brazil has achieved a series of more positive results, following a trend to leave already experienced in the last year of Michel Temer's presidency. This is mainly due to the measures taken by the until recently Minister of Justice and Public Security Sérgio Moro, former federal judge in charge of Operation Car Wash. Bolsonaro's choice of Moro as minister was not random, since Moro is considered by a large part of the population as a hero in the fight against corruption, due to the several trials he led against members of Odebrecht and the political class , including the one that would lead to the imprisonment of former president Lula da Silva. Having promised in the campaign a tough hand against crime and corruption, Bolsonaro decided to merge the ministries of Justice and Public Security and offer Moro its leadership.

The decision was a wise one and one of those that best sustained the Brazilian president's popularity in his first year in office, as test by a significant drop in the issue of violent crimes, including a 19% decrease in the issue of homicides. This is one of the most worrying indicators in Brazil, since it is the country with the highest gross annual homicide issue in the world. In 2018, homicides were 51,558, while in 2019 they dropped to 41,635, a decrease of 19.2%. Excluding larcenies from these figures, the decrease was from 49,120 to 29,750.

In addition, cargo thefts increased by 35% and drug seizures increased by 81%. In Rio de Janeiro, one of the most problematic states in terms of security, larcenies (robbery followed by death) were reduced by 34% and seizures of illegal weapons increased by 32%.

One of the measures that contributed most to this decline was the integration of the different state security force institutions at all levels: federal, state and municipal. This has allowed for a higher level of coordination, especially significant in the area of intelligence services, whose information now flows more easily between institutions. In addition, in this same area, it is worth mentioning the investments made in Big Data and intelligence systems. The main focus has been on facial recognition and video surveillance systems.

Another important policy has been the transfer of gang leaders to more isolated prisons, thus preventing them from communicating and coordinating with gang members on the outside.

Finally, the so-called "anti-crime package" should be mentioned: a series of laws and reforms to the penal code that increase the power of the security forces to act, in addition to establishing harsher penalties for violent crime, organized crime and corruption. The project C approved by the Brazilian Parliament is far from Moro's original proposal , but it has contributed, albeit to a lesser extent, to the decrease in crime.

On the other hand, these positive figures were accompanied by a worrying increase in accidental deaths in police operations, with several cases of children killed by stray bullets in shootouts between drug gangs and security forces going viral. In addition, the issue of provisional prisoners in Brazilian jails increased by 4.3% over the previous year. All this has encouraged criticism from most of the civil service examination and several human rights NGOs, both national and international.

In the first two months of 2020, 548 more deaths were recorded than in the same period of the previous year. This spike occurred in 20 of Brazil's 27 federal states, suggesting that this is a general trend rather than a sporadic episode. However, due to the mandatory quarantine library assistant in several states and municipalities, homicides fell again, making it difficult to extrapolate for the current year as a whole. Another factor to consider for 2020 is the recent resignation of Minister Moro; without him, the likelihood that the reforms initiated in the first year will continue is greatly reduced.

Argentina, Paraguay, Colombia and Honduras have already made C signal, while Brazil and Guatemala have pledged to do so shortly.

-

The 25th anniversary of the AMIA bombing served to trigger a cascade of pronouncements, breaking down the lack of adequate legal instruments against the group.

-

Several countries have established lists of terrorist organizations, allowing for greater coordination with the United States in the fight against terrorism in the region.

-

Hezbollah's involvement in illicit economies in the TBA and in drug trafficking networks explain the decision of the countries concerned in South and Central America.

![report to those killed in the AMIA bombing in Buenos Aires [Nbelohklavek]. report to those killed in the AMIA bombing in Buenos Aires [Nbelohklavek].](/documents/10174/16849987/hezbola-blog.jpg)

▲ report to the deceased in the AMIA bombing in Buenos Aires [Nbelohklavek].

report SRA 2020 / Mauricio Cardarelli [PDF version].

MAY 2020-The 25th anniversary of the largest terrorist attack in Latin America-the attack on the Argentine Israelite Mutual association (AMIA) on July 18, 1994-served as an opportunity for several countries in the region to announce their purpose to declare the Lebanese Shiite organization Hezbollah a terrorist group . Hezbollah is blamed for the AMIA bombing in Buenos Aires, which killed 85 people, as well as the bombing of the Israeli Embassy in the Argentine capital two years earlier, which killed another 22 people.

The year 2019, then, meant an important leap in the confrontation of Hezbollah in the Western Hemisphere, since previously no Latin American nation had declared as terrorist that organization, which is indeed designated as such by the United States, the European Union and other countries. In fact, the Latin American codes of law, beyond the guerrilla phenomenon itself, have hardly taken into account the external terrorist fact, since these are states that have not suffered as other parts of the planet the rise of international terrorism, especially so far this century and especially from the hand of Islamist radicalism.

The round of declarations was opened by Argentina itself in July, on the anniversary of the AMIA massacre. In mid-August it was Paraguay's turn, while Brazil then announced its intention to follow in the same footsteps. Then the United States catalyzed the process, so that in the framework the III Hemispheric Ministerial lecture on Combating Terrorism, held in mid-January 2020 in Bogota, both Colombia and Honduras proceeded to include Hezbollah in lists of terrorist organizations. For his part, the Guatemalan president-elect pledged to take a similar measure when he assumes the presidency.

The cataloguing already effectively carried out by Argentina, Paraguay, Colombia and Honduras (countries attentive to the activity of Hezbollah in the so-called Triple Border or to its involvement in drug trafficking), and the not yet executed, but supposedly imminent, cataloguing of Brazil and Guatemala should help in a more forceful fight against this radical group by the national security forces and in the sentences of the respective courts of justice.

If already in 2018 the arrest of part of the network of the Barakat clan represented a step forward in the police coordination of Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay in the shared border area (the Triple Frontier, a place of intense commercial activity and of financing and concealment of Hezbollah operatives, sheltered by elements of a large Muslim population), the steps of 2019 constitute a decisive action.

Infiltration in Latin America

Hezbollah militants and cells have been able to penetrate Latin America in the last decades, first of all by taking advantage of the Lebanese diaspora. As a result of the civil war experienced by Lebanon between 1975 and 1990, thousands of people emigrated to the American continent, sometimes settling in places where there was already a certain Arab presence, as was the case of Palestinians or Syrians. Although some of these immigrants were Christians, others were Muslims; awareness among the latter of the fight against Israel led to the formalization of networks for financing radical groups, in a process of money laundering from the profuse commercial activity - and also smuggling - carried out in many of these enclaves.

A strategic point in this dynamic has been the Triple Border, where some 25,000 people of Lebanese origin live, as well as other Arab groups: it is the area with the most Muslims in Latin America. The porous border connects Ciudad del Este (Paraguay), with 400,000 inhabitants; Foz de Iguazú (Brazil), with 300,000, and Puerto Iguazú (Argentina), with 82,000. It is a hotbed of illicit activities linked to money laundering, counterfeiting, smuggling and drug trafficking. Illicit trade in the tri-border area is estimated to be worth some US$18 billion a year. The authorities have been able to identify Hezbollah financing networks, as well as the presence of group operatives (the preparations for the Buenos Aires bombings of 1992 and 1994 were traced back to this tri-border enclave). Last year, Assad Ahmad Barakat and some fifteen members of his clan, dedicated to generating funds for Hezbollah, were arrested.

Other points of support for Hezbollah have been certain places in Brazil with mosques and radicalized Shiite cultural centers, which host activities of extremist clerics such as Bilal Mohsen Wehbe. On the other hand, Hugo Chavez's rapprochement strategy with Iran implied a close partnership manifested in the submission of Venezuelan passports to Islamists and their participation in the drug business under the protection of Chavez's leadership. This interrelation also contributed to its greater dispersion throughout the region, through Hezbollah's progressive ties with those who participate in the drug trafficking structure, such as the FARC or some Mexican cartels (Los Zetas and Sinaloa).

Signaling cascade

Argentina opened the round of Hezbollah finger-pointing (and creation, in most cases, of lists of terrorist groups, which did not previously exist in Latin American countries) on the 25th anniversary of the AMIA bombing, in July 2019. The then President Mauricio Macri, who had put an end to the Kirchnerist presidencies, of certain complicity with Iran, approved the creation of a public registry of persons and entities linked to acts of terrorism and its financing (RePET).

On the occasion of the important anniversary, the University Secretary of the Organization of American States (OAS), Luis Almagro, encouraged the countries of the continent to make this subject of declaration against Hezbollah.

Paraguay followed in Argentina's footsteps a month later. The government of Mario Abdo Benítez had been criticized for not acting decisively in the Triple Border, whose smuggling, such as tobacco, and other illicit activities feed the perception of corruption that accompanies the country's politicians. The Paraguayan president also plans to introduce a package of legislative reforms against money laundering.

Brazil announced on August 20 its intention to proceed in the same way as its two neighbors, although it has not yet implemented this decision. At the end of February 2020, Eduardo Bolsonaro, son of the Brazilian president and national deputy, confirmed that the step would be taken "soon"; he suggested that the delay in adopting the measure was due to the fact that the application of the terrorist group grade is also being considered for other organizations, such as Hamas.

In December it was the advertisement of Guatemala, whose elected president, Alejandro Giammattei, communicated that when he took position he would put Hezbollah on a black list. Giammattei linked the decision to a pro-Israeli policy that would also lead him to move the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, following the example of the United States (Honduras and Paraguay are also on the same line). Giammattei took office on January 14, but has not yet implemented his promises.

Behind these moves by Latin American countries was U.S. diplomacy. The deployment of this was evident in the third meeting of the Hemispheric Ministerial lecture on Combating Terrorism, an initiative promoted by Washington with Hezbollah in its sights, among other objectives. This meeting was held on January 20, 2020 in Bogota and was attendance by the US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo.

Colombia took advantage of the meeting, which it hosted, to announce its consideration of Hezbollah as a terrorist group . President Iván Duque announced that three days before the country's National Security committee he had adopted the U.S. and European Union lists of terrorist individuals and organizations. The approved list included the ELN guerrillas and FARC dissidents, and the former FARC disappeared from the list.

Honduras, the Central American country that is the most compliant with US strategies, also made its international advertisement in the same lecture. Its foreign minister commented at the end of a previousmeeting of the National Security and Defense committee that Honduras had designated Hezbollah as a terrorist group and proposed to create a registry of persons and entities linked to terrorism and its financing.

[A. Patanru, M. Pangestu, M.C. Basri (eds), Indonesia in the New World: Globalisation, Nationalism and Sovereignty. ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute. Singapore, 2018. 358 p.]

review / Irati Zozaya

The book consists of fifteen articles, written by different experts, on how Indonesia has dealt with globalization and what effect it has had on the country. The texts have been coordinated by Arianto A. Patunru, Mari Pangestu and M. Chatib Basri, Indonesian academics with experience also in public management , having served as ministers in different governments. The articles combine general approaches with specific aspects, such as the consequences of the opening up to international trade and investment in the mining industry or the nationalization of foodstuffs.

The book consists of fifteen articles, written by different experts, on how Indonesia has dealt with globalization and what effect it has had on the country. The texts have been coordinated by Arianto A. Patunru, Mari Pangestu and M. Chatib Basri, Indonesian academics with experience also in public management , having served as ministers in different governments. The articles combine general approaches with specific aspects, such as the consequences of the opening up to international trade and investment in the mining industry or the nationalization of foodstuffs.

To explain Indonesia's current status , the book occasionally recapitulates periods of its history. Precisely one of the concepts that comes up frequently in the book is that of nationalism: it could be said, according to the authors, that this is what has most marked Indonesia's relationship with the world, regardless of who has led this country of 260 million inhabitants at any given time.

The first part of the book reference letter more generally to Indonesia's experience with globalization, nationalism and sovereignty. They begin by showing the colonial era and how, due to the imposition by Holland and Great Britain of an opening to the world, a strong nationalist sentiment begins to emerge. After the occupation by Japan during the Second World War, a total autarchy was implemented, thus leading the citizens to a problem that is still very present in Indonesia today: the internship of smuggling. In 1945 the country achieved its long-awaited independence under the presidency of Sukarno, who closed Indonesia to the rest of the world to focus on reaffirming national identity and developing its capabilities. This led to the deterioration of the Economics and the consequent hyperinflation, which ushered in a new era: the New Order.

In 1967, with Suharto's accession to the presidency, a cautious opening to foreign trade and investment flows began. However, Suharto repressed political activity and during his tenure the military gained much influence and the government retained control over Economics. In addition, the end of his presidency coincided with the Asian financial crisis (1997-1998), which led to a fall in the country's economic growth and a slowdown in poverty reduction, and consequently a growth in inequality. The financial crisis undermined confidence in the president and culminated in the collapse of the New Order.

The next period addressed is the Reformasi, an era that marked the beginning of a more open and democratic political climate. The next two presidents, Abdurrahman Wahid (1999-2001) and Megawati Soekarnoputri (2001-2004), were more concerned with economic recovery and democratic consolidation and a protectionist system regarding Economics endured. The book does not focus much on the next president, Yudhoyono (2004-2014), remarking only that he was an internationalist who maintained a more cautious and ambivalent stance on economic issues.

Finally, in the 2014 elections, Joko Widodo came to power and holds the position of president today. Under him, Indonesia has returned to the path of economic growth and has stabilized as a reasonably successful democracy. As the president, commonly known as Jokowi, has taken new steps to emphasize political sovereignty and promote economic autarky and national cultural revival, his term has been characterized as 'new nationalism'. In his political speech , Jokowi puts Indonesia as a goal of foreign conspiracies and calls to be on guard against such threats. However, the country maintains an ambivalent stance towards international openness and cooperation since, although trade restrictions have increased again in recent decades, Jokowi emphasizes global engagement and has reactivated regional negotiations.

All this has led to public dissatisfaction with globalization, with up to 40% of citizens believing that globalization threatens national unity. One of the most negative and important effects in Indonesia is that of workers who have been forced to migrate and work abroad under very poor conditions. However, the later parts of the book also show the positive consequences that globalization has had in Indonesia, manifesting itself in higher productivity, increased wages or economic growth, among others. The authors therefore emphasize the importance of constructing a narrative that can generate public and political support for the opening up of the country and counteract the growing anti-globalization sentiment.

As it happens in a book that is the sum of articles by different authors, its reading can be somewhat heavy due to a certain reiteration of contents. However, the variety of signatures also implies a plurality of approaches that undoubtedly provides a wealth of perspectives for the reader.

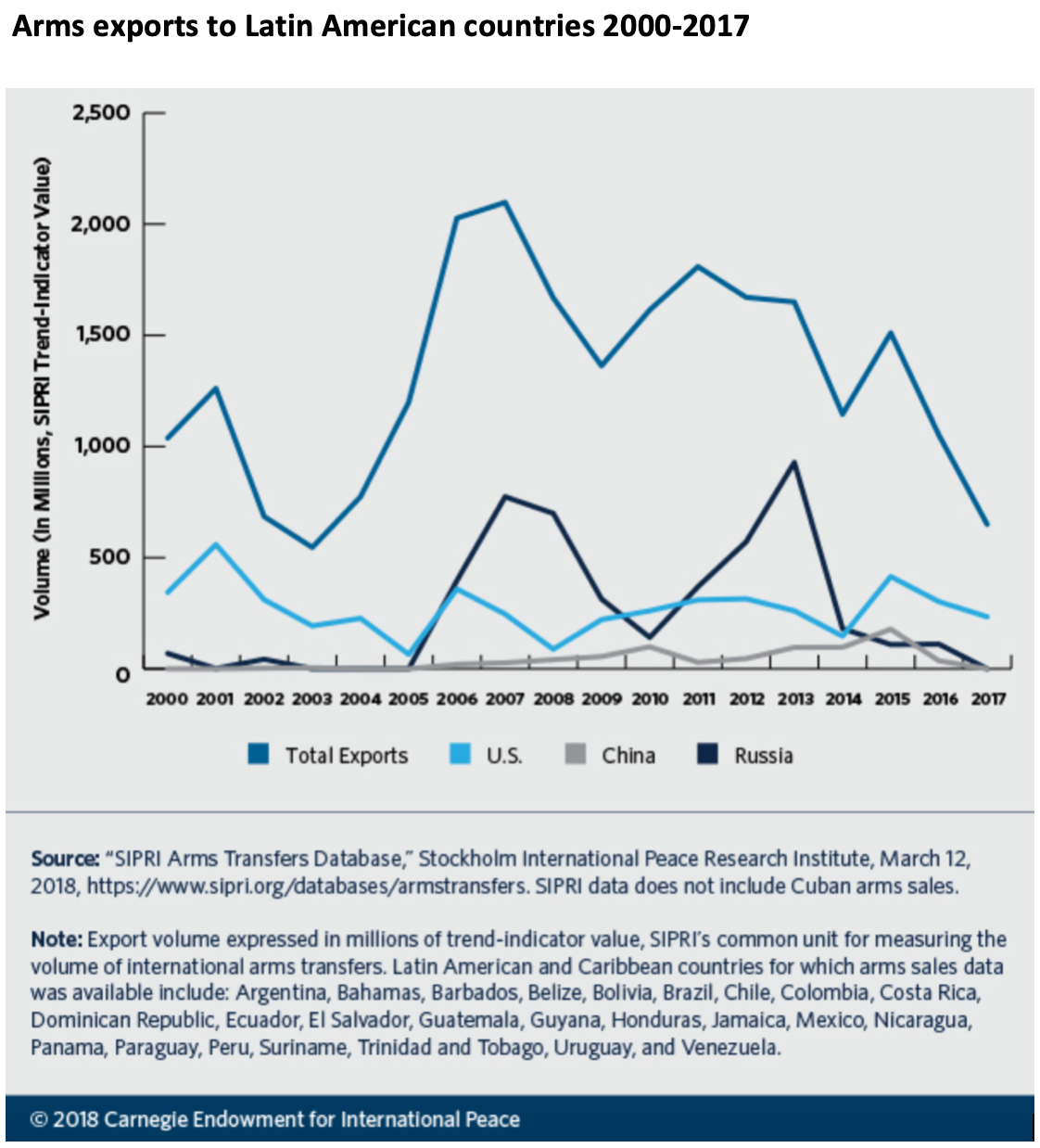

The region purchased only 0.8% of total Russian arm exports in 2015-2019; the US has recovered its position as the main arms supplier for the Americas

-

Over the last five years, the region carried out 40% less arms imports than during 2010-2014; the end of the commodity boom era reduced military equipment purchases

-

Chavez's Venezuela got almost $20 billion in Russian loans to buy weapons, but the collapse of the Venezuelan oil industry has left Moscow without a clear full repayment

-

The arrival of the Bolivarian left to power in many countries brought tight relations with Moscow. But the pink revolutions wave has subsided in almost all places.

![A Russian Sukhoi Su-30MK2 bought by Venezuela, in Barquisimeto in 2016 [Carlos E. Pérez]. A Russian Sukhoi Su-30MK2 bought by Venezuela, in Barquisimeto in 2016 [Carlos E. Pérez].](/documents/10174/16849987/rusia-armas-blog.jpg)

▲ A Russian Sukhoi Su-30MK2 bought by Venezuela, in Barquisimeto in 2016 [Carlos E. Pérez].

ARS Report 2020 / Peter Cavanagh[PDF version] [PDF version].

MAY 2020-Over the last two decades Latin America increased its military expenditure. As the Latin American countries improved their economies, they looked to modernize their military and defense systems. The purchasing spree was notorious during the golden decade of high commodity prices (2004-2014), especially during the first five years, which were the most profitable in public income terms. After the commodity boom was over the region lowered its military purchases.

The trend was not uniform. Meanwhile Central America and the Caribbean, less affected by the commodity cycle, kept increasing the expenditure in arms imports over the last years, South America, more depending on minerals and oil exports, reduced the volume of arms transfers. Taken the region as a whole, Latin America's military purchases were 10% of global arms transfers in 2010-2014, and 5.7% in 2015-2019, according to SIPRI. Between the two periods, arms imports by Latin America dropped 40%.

This general evolution was mirrored by the ups and downs of Russia's portfolio in the region. Moscow managed to exploit the opportunity of the golden decade to the fullest. Russia positioned itself as a willing partner in arms sales and became the leading arms exporter in the region, surpassing China and the United States by far. Russia tried to exert its influence in Latin America to the highest extent possible, taking advantage of a wave of leftist governments (the so-called pink revolutions). Latin America has traditionally fallen under the sphere of influence of the United States. With Russian arms sales in the region, it serves as a direct challenge to US influence. As the second largest exporter of military arms in the world, after the US, Russia has a unique opportunity to affect policy in the region.

However, it is important to note that from 2014 onwards, Latin American arms imports have really begun to drop off, and this includes Russian exports as well. Russian arms exports decreased by 18% globally between 2010-2014 and 2015-2019, first affected by a prominent drop of purchases by India (-47%), which is its main client (25% of Russia's sales in that period), and, less importantly, by a reduction of imports from the Americas. Russian sells to Latin American countries were only 0.8% of total Russian military exports. From 2014 onwards the US recovered its traditional position as the main arms supplier for the region.

Countries

In the last two decades Venezuela has been Russia's biggest customer in the Western Hemisphere. Since the mid 2000's, after Hugo Chavez consolidated his power, Venezuela has purchased almost $20 billion in military equipment from Moscow. The years 2005 and 2006 saw the beginning of the transactions: Russian loans for Chavez's government to buy arms in exchange of future Venezuelan oil deliveries.

Over the years Caracas carried out more than thirty operations of arms acquisitions. more than the number of operations done by the other countries combined: Mexico 7, Peru 6, Nicaragua 5, Brazil 4, Colombia 3, Ecuador 2, and Argentina, Uruguay and Cuba 1 each. Among other significant material Venezuela acquired 24 Sukhoi fighters Su-30MK2s (and ordered 12 more), the S-300 surface-to-air missile system, various combat and transport helicopters such as the Mi-35M and Mi-26 models, and 92 T-72M1 tanks.

The prospects of Russia getting all its money back any time soon from Venezuela is quite low. Due to the severe economic conditions of the country, Venezuela has not been able to continue its payments, so the terms of the debt had to be renegotiated. Since 2014 Moscow has not delivered any new material. After the withdrawal of the giant Russian energy company Rosneft from the country at the beginning of 2020 there have been fewer ways for the Russians to recover the loans. In many respects, this has left Venezuelan-Russian relations at a crossroads.

As Venezuela continues to decline rapidly, Russia is faced with deciding whether to keep making large investments in a country where it is tremendously risky or just abandon all efforts which have been made over the past few decades. Only time will tell which course of action the Kremlin will take.

Besides Venezuela there are a handful of other nations which have also carried out arms deals with Moscow. Nicaragua for example has been the beneficiary of many arms deals. According to the SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, in the first decade of the 21st century almost no arms orders had been made. However, this changed two years after Daniel Ortega came to power in 2007. Since then 90% of all military imports that Nicaragua has received have been supplied by Russia. In 2016, 50 T-72B1 Russian tanks were shipped to Nicaragua as part of a reported $80 million deal. Then in 2017 two Antonov An-26 military transport aircraft were sent.

The Nicaraguan government justified these purchases, saying that the equipment would be used as part of the struggle against drug trafficking. However, this has caused many other Latin American nations to become concerned of a military imbalance in the region, especially because some of the new equipment is more proper for waging war rather than keeping internal security.

Reports on Nicaraguan-Russian relations point to the fact that Russia may have ulterior motives beyond just influence. In many ways it comes down to military real estate. The arms deals between the two countries has been seen as an attempt on the part of Russia to curry favor with the Nicaraguan government in attempts to gain access refuelling facilities by the equator.

Other significant Russian arms sales recipients, as already mentioned, include states such as Peru, Mexico and Brazil. In the case of Peru, a country that even during the Cold War had some Soviet weapons systems in its inventory in order to diversify its arm imports, the most recent deal occurred between 2014 and 2016 valued at approximately half a billion dollars: the purchase of 24 transport helicopters Mi-8MT and Mi-17 (another 24 units were ordered in 2017).

Mexico has not Russians among its main arms suppliers (64% of Mexican purchases were to the US in the period 2015-2019; 9.5% to Spain and 8.5% to France), but still it carried out six arms deals with Russia since 2000. There has not been a deal made since 2011 when three Mil Mi-17 Military helicopters were purchased.

Brazil has also had a handful of deals with Russia in recent years, during the presidencies of Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff, when an amore pro-Russia stance was held by the government. This has changed immensely since the election of Jair Bolsonaro in 2018. The Brazilian government is now openly concerned for Russian influence in the region and has begun to take a more pro-USA stance when it comes to foreign policy. In any case, in the period 2015-2019 the main arms suppliers to Brazil were France (26%), the US (20%) and the UK (17%).

Overall, Russian arms sales to Latin America grew considerably, with some fluctuations, over the course of the last twenty years. The latest trend however has been a significant drop in overall Russian arms exports to Latin America. Between 2015 and 2019, as already mentioned, Latin America accounted for only 0.8% of all Russian arms exports.

This drop can be attributed to two main factors. In the first place, the change of ideological orientation in the Latin American countries, with less leftist parties in power. Secondly, the end of a booming economy in the region. And additional reason could be the international sanctions against some specific Russian industries due to the aggressive foreign policy conducted by Putin.

Spain sells less defense material to Latin American countries than it would be entitled to according to the trade Issue

-

In 2019 there was a recovery in Spanish arms sales to Latin America, surpassing 2018 figures, which were the lowest in a long time

-

In the last five years, Spain sold 691.2 million euros worth of defense material to the region, 3.6% of its world arms exports.

-

Mexico (24.8%), Ecuador (22.5%), Brazil (16.1%), Peru (14.4%) and Colombia (8.6%) are the five countries that purchased the most material from Spain in the last five years.

![Airbus NH90 helicopter, whose final assembly is carried out at Airbus Military facilities in Spain [Airbus]. Airbus NH90 helicopter, whose final assembly is carried out at Airbus Military facilities in Spain [Airbus].](/documents/10174/16849987/espana-armas-blog.jpg)

▲ Airbus NH90 helicopter, with final assembly at Airbus Military facilities in Spain [Airbus].

report SRA 2020 / Álvaro Fernández[PDF version] [PDF version].

MAY 2020-Latin American countries are an area of clear commercial interest for Spain. However, despite being the seventh largest exporter of armaments in the world and therefore particularly active in this sector, Spain sells less defense material to Latin America and the Caribbean than it would be entitled to by the overall export quota it maintains with the region.

If between 2014 and 2018 Spain maintained its overall export of products to Latin America between 5.3% and 6.5% of its global exports, in the case of the arms sector it moved around 3.2% in 2016 and 2017 and fell to 1.06% in 2018. It is to be expected that this minimum percentage will have risen again in 2019, a year for which there are still no complete official data , but in view of those of the first semester , it would seem that it will not even be close to 3%.

The explanation for this lower weight of arms exports in the overall Spanish exports to Latin America can be found in two facts. One is the smaller budget dedicated to the purchase of this subject of material by most Latin American countries, compared to some large buyers(in 2018 Spain's first customer was Germany - in turn the fourth largest exporter in the world -, which cornered 33% of Spanish sales). The other is that Latin American nations have other important market options: the United States, Russia and China (first, second and fifth largest arms exporters in the world; France is the third).

In 2018 there was a significant drop in Spanish defense exports to Latin America, which were 38.3 million euros, well below any of the preceding years. Partial data for 2019 indicate a recovery, although without reaching the figures recorded in 2015, when a peak of €239.4 million was reached, or those of the previous years of 2016 and 2017, when they were €130.7 million and €139.3 million, respectively.

The decline in 2018 corresponds to a smaller purchase list from most Latin American customers. Of the five largest customers over the past five years, Colombia was the only one to maintain a similar level of purchases, worth €11 million. Colombia and the next largest buyer, Mexico, were the only ones to slightly increase their imports in 2017, although they were lower than in previous years. The reduction was significant for the next two customers in 2018, Brazil and Peru. That year marked a further reduction in imports by Ecuador, which over the five-year period has been steadily cutting its order book to Spain.

The figures considered in this article only take into account defense material, not other subject material, which the administrative office of State of Commerce considers separately, such as riot control material, hunting and sporting weapons, as well as dual-use technology products.

General and Latin American sales

Spain has around 130 companies dedicated to the armaments sector. Among them are Airbus Military, Navantia and Indra, which are among the 100 largest defense and security companies in the world. Most of the sector are private companies, although there are some unique cases of public ownership, such as Navantia, dedicated to shipbuilding, both civil and military, created in 2005 when the assets of another public business , the IZAR group , were spun off.

According to the official data of the administrative office of State of Commerce, the issue of exports of defense material has been increasing notably during the last years. More than half of the Spanish arms exports during 2018 and the first semester of 2019 had as recipients countries belonging to NATO or the European Union. In 2017 they exceeded 4.3 billion euros, after several years of rises in this market. In contrast, arms worth €3,720.4 million were sold in 2018, which was 14.4% less. The first semester of 2019, however, saw an improvement, reaching €2,413 million, an increase of 41.5% compared to the same period of the previous year.

As regards trade with Latin America, between 2014 and 2018 Spain sold military equipment worth €691.2 million to the region, a figure that represents 3.6% of the total of €19,042 million exported by Spain for arms.

In the five years as a whole, the first importer was Mexico, which with purchases worth 171.4 million euros (of which 140.9 million corresponded to 2015 alone), acquired a quarter (24.8%) of the defense material sold by Spain to Latin America in that five-year period. As the second country, Ecuador stands out, with 155, 7 million and 22.5% (slightly more than half -85.9 million- were purchases made only in 2014). It is followed by Brazil, which made more regular acquisitions throughout this time, with 111.8 million and 16.1%); Peru, with 99.5 million and 14.4% (the largest amount -78.4 million- was executed in 2017), and Colombia, with 59.5 million and 8.6%.

Some countries

Mexico figures as the first buyer of Spanish defense material in the last five years (2014 and 2018) due to purchases made in 2015, when it acquired four transport aircraft, worth €127.2 million. In 2018 it only imported €10.1 million in parts, pieces and spare parts for Spanish-made aircraft, equipment for engines of an aircraft derived from a European cooperation program and instruments of an air surveillance system.

Brazil is one of the countries with the greatest diversity in the destination of its imports. In recent purchases, 19.7% were for private business , 74.2% for the Armed Forces and the remaining 5.9% were for individuals. In 2018, it purchased €7.9 million in pistols, rifles and magazines for private individuals, as well as day sights, spare parts for armored vehicles and spare parts for Spanish and U.S.-made aircraft for the Armed Forces.

Colombia imported in 2018 a total of €11 million in spare parts for artillery howitzer maintenance, artillery ammunition, spare parts for Spanish and U.S.-made armored vehicles, and parts for Spanish-made transport aircraft.