Breadcrumb

Blogs

[Barbara Demick, Dear Leader. Living in North Korea. Turner. Madrid, 2011. 382 pages]

review / Isabel López

All dictatorships are the same to some extent. Regimes such as Stalin's, Mao's, Ceausescu's or Saddam Hussein's shared the installation of statues of these leaders in the main squares and their portraits in every corner... However, Kim Il-sung took the cult of personality in North Korea further. What set him apart from the rest was his ability to exploit the power of faith. That is, he understood very well the power of religion. He used faith to attribute to himself supernatural powers that served to glorify him staff, as if he were a God.

All dictatorships are the same to some extent. Regimes such as Stalin's, Mao's, Ceausescu's or Saddam Hussein's shared the installation of statues of these leaders in the main squares and their portraits in every corner... However, Kim Il-sung took the cult of personality in North Korea further. What set him apart from the rest was his ability to exploit the power of faith. That is, he understood very well the power of religion. He used faith to attribute to himself supernatural powers that served to glorify him staff, as if he were a God.

This is what it looks like in Dear Leader. Living in North Korea, by journalist Barbara Demick, who worked as a correspondent for the Los Angeles Times in Seoul. The book chronicles the lives of six North Koreans from the city of Chongjin, located in the far north of the country. Through these six profiles, from people belonging to the class more leave, called Beuhun, to the class Demick exposes the different stages that have marked the history of North Korea.

Until the conquest and occupation of Japan in the 1905 war, the Korean empire ruled. During the rule of the neighboring country, Koreans were forced to pay high taxes and young men were taken with the Japanese army to fight in the Pacific War. After the withdrawal of Japanese troops in 1945, a new problem arose as the Soviet Union had occupied part of northern Korea. This led to the U.S. getting involved to slow the advance of the Russians. As a consequence, the territory was divided into two zones: the southern part occupied by the United States and the northern part occupied by the Soviet Union. In 1950 both factions were embroiled in the Korean War, which ended in 1953.

After the armistice there was a exchange Communist forces released thousands of people, more than half of whom were South Koreans. However, thousands of others never returned home. The freed prisoners were loaded into wagons departing from the Pyongyang station with the presumed intention of returning them to their place of origin in the south, but in reality they were driven to the coal mines of northern Korea, on the border with China. As a result of the war, the population had mixed and it was not possible to distinguish between North and South Koreans.

At the end of the war, Kim Il-sung, leader of the Workers' Party, began by purging all those who might endanger his leadership, based on a criterion of political reliability. Between 1960 and 1970, a regime was established that the author describes as one of terror and chaos. Each citizen's background was subjected to eight checks and a classification was established based on the past of their relatives, eventually becoming a caste system as rigid as India's. This structure was largely based on the system of Confucius, although the less amiable elements of it were adopted. Finally, the social categories were grouped into three classes: the principal, the vacillating, and the hostile. The latter included soothsayers, artists, and prisoners of war, among others.

Those belonging to the class more leave They had no right to live in the capital or in the most fertile areas and were closely watched by their neighbors. In addition, the so-called inminban were created, a term that reference letter to the cooperatives formed by about twenty families who managed their respective neighborhoods and who were responsible for transmitting any suspicion to the authorities. It was impossible to rise through the ranks, so it was passed down from generation to generation.

Children were taught respect for the party and hatred for Americans. The Education It was compulsory until the age of 15. From then on, only children belonging to the upper classes were admitted to the school. Education high school. The smartest and prettiest girls were taken to work for Kim Il-sung.

Until the end of the 1960s, North Korea seemed much stronger than South Korea. This caused public opinion in Japan to align itself in two camps, those who supported South Korea and those who sympathized with the North, called Chosen Soren. Thousands of people succumbed to the propaganda. The Japanese who emigrated to North Korea lived in a different world from the North Koreans since they received money and gifts from their families, although they had to give part of the money to the regime. However, they were considered part of the class hostile, since the regime did not trust anyone wealthy who was not a member of the party. Their power depended on their ability to totally isolate the citizens.

The book chronicles Japan's relationship with North Korea and its influence on the development economic of this. When Japan decided to build an empire in the early 20th century, it occupied Manchuria and took over the iron and coal deposits near Musan. For the transport of the booty, the city of Chongjin was chosen as a strategic port. Between 1910 and 1950 the Japanese erected huge steel mills and founded the city of Nanam, in which large buildings were built. development of North Korea. Kim Il-sung exhibited industrial power by taking credit for it and did not recognize any of Japan's credits. North Korean authorities took control of the industry and then installed missiles aimed at Japan.

The author also describes the lives of women workers in the factories that supported the development of the country. Factories depended on women because of the lack of male labor. A factory worker's routine, which was considered a privileged position, consisted of eight hours a day, seven days a week, plus the added hours to continue her work. training Ideological. Assemblies such as the socialist women's assembly and self-criticism sessions were also organized.

On the other hand, it emphasizes the extent to which people were molded, that they were regenerated to see Kim Il-sung as a great father and protector. In his purpose Kim Il-sung developed a new philosophical system based on the thesis Marxists and Leninists called Juche, which translates as self-confidence. He made the Korean people see that he was special and that he had been the chosen people. This thought captivated a community that had been trampled by its neighbors for centuries. He taught that the strength of human beings came from the ability to submit their individual will to the collective and that this collectivity should be ruled by an absolute leader, Kim Il-sung.

However, this idea was not enough for the leader, who also wanted to be loved. The author states that he "did not want to be seen as Stalin but as Santa Claus": he should be considered as a father in the Confucian style. Indoctrination began in kindergartens. For the next few years they wouldn't listen to any songs, they wouldn't read any article that he was not deifying the figure of Kim Il-sung. Lapel badges with his face were distributed, which were obligatory to wear on the left side, over the heart, and his portrait had to be in every house. Everything was distributed free of charge by the Workers' Party.

![Qasem Soleimani receives a decoration from Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in early 2019 [Khamenei's Office] Qasem Soleimani receives a decoration from Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in early 2019 [Khamenei's Office]](/documents/10174/16849987/tension-oriente-medio-blog.jpg)

▲ Qasem Soleimani receives a decoration from Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in early 2019 [Khamenei's Office]

COMMENT* / Salvador Sánchez Tapia

The death in Iraq of General Qasem Soleimani, head of the Iranian Quds force, at the hands of a US drone is one more link in the process of growing deterioration of the already bad relations between the United States and Iran, the latest chapter of which has been experienced since 2018, the year in which President Trump decided to break the so-called "agreement (JCPOA) signed with Iran in 2015 by the Obama administration and the other members of the G5+1.

The attack on Soleimani, carried out in retaliation for the death of a US contractor in an attack apparently launched by the Iraqi Shiite militia Kataib Hezbollah on the US K1 base in Kirkuk on 27 December, has marked a qualitative change in the situation in the country. subject response that the U.S. is accustomed to give to incidents of this kind. subject for, for the first time, the goal It's been a stop manager of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Immediately after the assassination, during the funeral for the deceased general, Ali Khamenei, Iran's supreme leader, announced in somewhat apocalyptic terms that the attack would not go unanswered, and that it would come directly from Iranian hands, not through proxies. It came, in fact, on the night of January 8 in the form of a massive missile attack on two instructions U.S. military personnel stationed in western Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan. Contradicting Iranian statements that the bombings had killed some 80 Americans, the U.S. administration was quick to assert that there had been no casualties. leave because of the attacks.

In the aftermath of this new attack, the world held its breath waiting for an escalation by Washington. However, President Trump's statements on January 8 seemed to defuse tensions by arguing that the absence of U.S. casualties was indicative of an Iranian attempt to de-escalate. The U.S. will not respond militarily, although it has announced its intention to tighten the economic sanctions regime until the country changes its attitude. With this, the risk of an open war in the region seems averted, at least momentarily.

Are we affected by the tension between the United States and Iran?

Obviously, yes, and in several ways. First of all, we cannot ignore the fact that several European countries, including Spain, maintain significant military contingents deployed in the region, operating within the framework of NATO, the United Nations and the European Union in missions such as "Inherent Resolve" in Iraq, "Resolute Support" in Afghanistan, UNIFIL in Lebanon, "Active Fence" in Turkey, etc. or "Atalanta" in the Horn of Africa.

In the cases of Iraq and Afghanistan in particular, the Spanish troops deployed in the aforementioned missions work closely partnership with other NATO allies, including the United States. Although in principle Spanish soldiers – or, for that matter, those of the other NATO nations – are not in the crosshairs of Iranian responses, specifically directed against North America and its interests, there is no doubt that any attack by Iran on American units could collaterally affect the contingents of other nations operating with them. if only for a matter of mere geographical proximity.

Less likely is that Iran would attempt a response against any non-U.S. contingent through one of its proxies in the region. This would be the case, for example, of Hezbollah in Lebanon, a country in which Spain maintains a significant contingent whose security could be affected if it group, either on its own initiative, or at the behest of Iran, attempts to attack any UNIFIL unit or facility. This option, as we say, is considered unlikely because of the negative impact it would have on the international community in general, and because of the proximity to Israel of the deployment of UNIFIL.

The escalation has led to an increase in the alert level and a reinforcement of U.S. troops in the region. If the increase in tension were to continue, it would not be out of the question that Washington could come to some sort of agreement. subject It could appeal to the support of its partners and allies, either with troops or resources. It is difficult to determine at what time and under what conditions such a situation might occur application, for what purpose and, very importantly, what response Europe would give to it, taking into account the concern with which the Old Continent observes an escalation in which it is not interested, and the state of relative coldness that relations between the United States and Europe are going through.

As a result of the assassination, Iran has made public its intention to dissociate itself completely from the provisions of the agreement that I was still watching. In other words, he says he feels free to continue his nuclear program. Undoubtedly, this last nail in the coffin of the JCPOA may lead to an open degree program nuclear power in the region with negative consequences for regional security, but also for European security. The rise of the issue From our point of view, the collapse of nuclear powers is, in itself and from our point of view, bad news.

Finally, and as a side effect of the escalation, the price of a barrel of oil is beginning to show a disturbing upward trend. If there are no corrective measures by increasing production from other countries, the trend could continue. There is no need to dwell on what the increase in the price of oil means for the economy. Economics and, of course, for the national one.

Russia and China in the crisis

Russia is making efforts to replace the United States as the leading power in the region and to present North America as a leading power. partner unreliable, which abandons its allies in difficulty. The escalation of the crisis could have a negative impact on this effort, delaying it or, in the worst case, ending it if, in the end, the United States were to reverse its policy of gradual derailing withdrawal in the Middle East due to an increase in tension with Iran. Russian rhetoric will be anti-Washington. In the end, however, it will do nothing to increase the tension between the United States and Iran, and it will, probably, keep it within a tolerable level or decrease.

Russia is not so much a staunch ally of Iran as one of convenience. Iran is a competitor of Russia for influence in the region – particularly in Syria – and may seek to negatively influence Islamism in the Russian Federation. On the other hand, Russia is not enthusiastic about the idea of Iran acquiring nuclear weapons.

China's stance is conditioned by its heavy dependence on the steady flow of oil from the Middle East. For this reason, it has no interest in the instability that this increase in tension entails. It is expected to act as an element of moderator, seeking to use the crisis as an opportunity to increase its influence in the region. China is not interested per se in becoming the arbiter of security in the region, but it is interested in a stable, trade-friendly region.

The project "One Belt, One Road" is another reason why China will try to keep the crisis within acceptable limits. The Middle East is an element core topic in the project recreation of a sort of new Silk Road. An open war between the U.S. and Iran could adversely affect the country. project.

In summary, neither Russia nor China are interested in an escalation between the United States and Iran that could lead to an open war between the two nations that would jeopardize oil supplies, in the case of China, and the establishment as the main international power in the region, in the case of Russia. Both will try to temper the Iranian response, even if, at the level of statements, they speak out against the assassination of Soleimani.

* This text extends a previous comment made by the author to El Confidencial Digital.

The Brazilian Congress has approved to ratify the Technological Safeguards Agreement signed by Presidents Trump and Bolsonaro

With the reactivation of the launch site in Alcântara, the world's most perfectly placed launch site due to its proximity to the Equator, the Brazilian space industry hopes to achieve 10 billion dollars a year in business deals by the year 2040, with control of at least 1% of the global market, especially in space launches. The Bolsonaro administration has accepted the Technological Safeguards Agreement with the USA, an agreement that has evaded Washington before the Workers Party arrived to power.

![area space launch facility at the Brazilian Alcantara space centre [AEB]. area space launch facility at the Brazilian Alcantara space centre [AEB].](/documents/10174/16849987/alcantara-blog.jpg)

▲ Launch premises at the Brazilian launch site in Alcântara, near the Equator [AEB]

ARTICLE / Alejandro J. Afonso [Spanish version]

Brazil wants to be a part of the new Space Age, where private companies, especially from the United States, are going to be the protagonists, alongside with the traditional national space agencies of the global powers. With the Technological Safeguards Agreement, signed in March 2019 by President Donald J. Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, the strategic Alcântara launch site will be able to launch rockets, spacecraft and satellites equipped with American technology.

The guarantee of technological confidentiality - access to some areas of the base will be authorized only to American personnel, although the jurisdiction of the base will remain with the Brazilian Armed Forces - will permit that Alcântara need not negotiate contracts with only 20% of the global market, as it has been until now, something that has held back the economic rentability of the base. However, this agreement is also limiting, in that Brazil is only authorized to launch national or foreign rockets and spacecraft that are composed of technology that has been developed by the United States.

The new political landscape in which Brazil finds itself has permitted the agreement to be ratified without issue on the 22nd of October by the Chamber of Deputies and on the 12th of November by the Senate, a very different situation than that of 2000, when the Brazilian Congress blocked the agreement proposed by then president Fernando Henrique Cardoso. The subsequent arrival to power of the Workers Party, with the presidency of Luiz Inácio Lula de Silva and Dilma Rousseff, froze relations between Brazil and the United States, leading Washington to momentarily set aside its interest for Alcântara.

The Alcântara Launch Site is situated in Maranhão, a state in north northeast Brazil. Alcântara is a small colonial town that sits 100 kilometers away from the state capital of São Luís. The town has 22,000 inhabitants and access to the sea. The launch site was constructed during the 1980s, and has to campus 620 kilometers squared. Furthermore, the launch site is located 2.3 degrees south of the Equator, making the site an ideal location for launching satellites into geostationary orbit, meaning that the satellites remain fixed over one area of earth during rotation. The unique geographical conditions of the launch site, which facilitates the launch of rockets for geostationary orbit, attracts companies that are interested in launching small or medium satellites, usually used for communications or surveillance satellites. Unfortunately, the institution suffered a bad repute when operations were briefly halted due to a failed launch in 2003, resulting in the deaths of 21 technicians and the destruction of some of the installations.

The United States is interested in the Alcântara Launch site due to its strategic location. As mentioned previously, the launch site is located 2.3 degrees south of the Equator, thus allowing US rockets to save up to 30% on fuel consumption in comparison to launches from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Likewise, due to its proximity to the Equator, the resistance to reach orbit is lesser than Cape Canaveral, meaning that companies can increase the weight of the rocket or of the load it is carrying without adding additional fuel5. Thus, this location offers American companies the same advantages enjoyed by their European counterparts who utilize a launch site in French Guiana, located nearby, north of the Equator. The Technology Safeguards Agreement signed between Presidents Bolsonaro and Trump in March is meant to attract these American companies by ensuring that any American companies using the Alcântara launch site will have the necessary protection and safeguards to ensure that the technology used is not stolen or copied by Brazilian officials.

Brazil's space aspirations are not new; the Brazilian Space industry is the largest in Latin America. In the 1960s, the Brazilian government constructed their first launch site, Barreira do Inferno, close to the city of Natal. In 1994, the military's space investigation transformed into the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB), a national agency. In addition to the development of satellites, in 2004 the AEB launched their first rocket. Furthermore, in 2006 Marcos Pontes became the first brazilian astronaut to incorporate into the International Space Station, of which Brazilian is a partner.

The Brazilian government is clearly interested in the Americans using the Alcântara launch site. The global space industry is worth approximately 300 billion USD, and Brazil, who still has a developing space agency, could utilize funds earned from leasing the launch site to further develop their space capabilities7. The Brazilian Space Agency (AEB) has been underfunded for many years, and could do with the supposedly 3.5 billion USD that will come with American use of the Alcântara Launch Site. Furthermore, Brazilian officials have speculated that investment into the launch site will bring with it further investment into the Alcântara region as a whole, improving the quality of life there. In conclusion, the Brazilian government led by Jair Bolsonaro hopes that with the signing of this TSA the relationship between the US and Brazil deepens, and with this deepened relationship comes monetary means to invest in the launch site and its surrounding areas, and invest in the Brazilian Space Agency.

However, this agreement does not come without its critics. In 2000, the government of Brazilian president Fernando Henrique Cardoso tried to sign a similar agreement with the Bush administration that was eventually blocked by the Brazilian congress in fear that Brazil would be ceding its sovereignty to the United States. These same fears are still present today. Brazilian former Minister of Foreign Affairs Samuel Pinheiro Guimarães Nieto stated that the United States is seeking to establish a military base within Brazil, thus exercising sovereignty over Brazil and its people. Criticism is also directed to the wording of the agreement itself, stating that the money that the Brazilian government earns from American use of the launch site cannot be invested into Brazilian rockets, but can be invested in other areas concerning the Brazilian Space Agency.

In addition to the arguments concerning the integrity of Brazilian sovereignty is also a defense of the Quilombolas, descendants of Brazilian slaves that escaped their masters, who were displaced from their coastal land when the base was originally built. Currently, the government is proposing to increase the size of the Alcântara launch site by 12,000 hectares, and the Quilombo communities fear that they will once again be forced to move, causing further impoverishment. This has garnered a response in both the Brazilian congress as well as the American Congress, with Democrat House Representatives introducing a resolution calling on the Bolsonaro government to respect the rights of the Quilombolas.

The Technology Safeguards Agreement is a primarily commercial agreement in order to attract more American companies to Brazil for an ideal launch site in Alcântara, which would save these companies money due to the ideal location of the launch site while investing in the Brazilian economy and space program. However, due to the controversies listed above, some may consider this a one sided agreement where only American interests prevail, while the Brazilian government and people lose sovereignty over their land. At the same time, one point could be made: Brazil has traditionally developed an important aeronautic industry (Embraer, recently bought by Boeing, is an outstanding example) and the Alcântara base gives it the opportunity of jumping into the new space era.

![A demonstration in Beirut as part of 2019 protests [Wikimedia Commons] A demonstration in Beirut as part of 2019 protests [Wikimedia Commons]](/documents/10174/16849987/libano-blog.jpg)

▲ A demonstration in Beirut as part of 2019 protests [Wikimedia Commons]

ESSAY / David España Font

1. Introduction

A shared feeling has been rising across the globe for the last three years, but with special strength during the last six months. The demonstrations since February in Algeria, since September in Egypt, Indonesia, Peru or Haiti, and in Chile, Iraq or Lebanon since October are just some manifestations of this feeling. The primary objective of this essay will not be to find a correlation among all demonstrations but rather to focus on the Lebanese governmental collapse. The collapse of the Lebanese government is one example of the widespread failure most politicians in the Middle East have to meet public needs. [i]

Regarding the protests that have been taking place in Egypt and the Levant, it is key to differentiate these uprisings from the so-called Arab Spring that took place in 2011, and which caused a scene of chaos all over the region, leading to the collapse of many regimes. [ii] The revolutionary wave from 2011, became a spark that precipitated into many civil wars such as those in Libya, Yemen or Syria. It is important to note that, the uprisings that are taking place at the moment are happening in the countries that did not fall into civil war when the Arab Spring of 2011 took place.

This essay will put the focus on the issue of whether the political power in Lebanon is legitimate, or it should be changed. Are the Lebanese aiming at a change in leadership or rather at a systemic change in their political system? This essay id divided into four different parts. First, a brief introduction summarizes the development of the October demonstrations. Second, it throws a quick overview into recent political history, starting from the formation of the Lebanese state. Third, it will approach the core question, namely which type of change is required. Finally, a brief conclusion sums up the key ideas.

2. October 2019

On Thursday October 17th, thousands of people jumped into the streets of Beirut to protest against political corruption, the nepotism of the public sector and the entrenched political class. There hadn't been a manifestation of public discontent as big as this one since the end of the civil war in 1990. The demonstration was sparked by the introduction of a package of new taxes, one of which aimed at WhatsApp calls. [iii] Roads were blocked for ten days in a row while citizens kept demanding for the entire political class to resign. Although, apparently, the demands were the same as those forwarded in 2011, the protests might have been looking more for a change in the whole political system than for mere changes in leadership.

It must not be forgotten the fact that Hasan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, warned that such protests could lead to another civil war and that the right to demonstrate had to be abolished as soon as possible. He literally stated: "I'm not threatening anyone, I'm describing the situation. We are not afraid for the resistance; we are afraid for the country." [iv] Certainly, a change in the political power could make such a power notably stronger, Hezbollah is now enjoying the weakness of the Lebanese political power and prefers to maintain the status quo.

This arising conflict must be analysed bearing in mind the very complicated governmental structure which seems to be very effective towards conflict avoidance, but not towards development and progress. The country is governed by a power-sharing system aimed at guaranteeing political representation for all the country's 18 sects. [v] Lebanon's government is designed to provide political representation of all Lebanese religious groups, the largest ones being the Maronites, the Shiite and the Sunni. The numbers of seats in the Parliament is allotted among the different denominations within each religion. The President must always be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni and the Speaker of Parliament as Shiite. [vi]

Therefore, it goes without saying that the structure of the political power is designed for survival rather than for coexistence. Each representative is inclined to use his position in favour of the interest of the sects that he belongs to instead of that of the national, common interest. There is no chance for common policies to be agreed as long as any of these interfere with the preferences of any one of the sects.

3. A quick overview into recent history

Since the end of the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire managed to control all the region today known as Levant and Egypt. However, the area known as Mount Lebanon remained out of its direct influence[vii]. The region became a self-governed area controlled by powerful Christian Maronite families. Because the Ottoman Empire did not allow European Christians to settle in the territory and benefit from trading activities, the Europeans used the Lebanese Maronites as their commercial representatives. [viii] This was one of the main ways how the European legacy penetrated the region, and one of the reasons that explains why Christians in Lebanon and Syria had a good command of French even before the arrival of the French mandate, and why they became, and still are, richer than the Muslims.

Following World War I, the League of Nations awarded France the mandate over the northern portion of the former Ottoman province of Syria, which included the region of the Mount Lebanon. This was a consequence of the signature in 1916 of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, by which the British and the French divided the Middle East into two areas put under their control. The British would control the South, and the French the North. [ix]

In 1920 the French carved out the region of Lebanon from their mandated area. The region would later be granted the independence in 1943. The means of such demarcation had as primary objective the guarantee and protection of the Christian's free and independent existence in the Muslim Arab world, not even the protection of their rights but rather the recognition of their existence. Since the very first moment of Lebanon's establishment as a separate territory from Syria, Sunni Muslims rejected the very idea of a Lebanese state which was perceived as an act of French colonialism with the objective of dividing and weakening what was perceived to be the united Arab Nation. [x]

Because the preservation of the greater Lebanon was the primary objective for the Christians and they were not going to give up that objective for the sake of a united Arab Nation, a gap between the Maronite and the Sunni communities opened that had to be closed. The legal agreement that came up from efforts in this sense came to be known as the National Pact of 1943 "al-Mithaq al-Watani." [xi] At the heart of the negotiations was on the one hand the Christians' fear of being overwhelmed by the Arab countries, and on the other hand the Muslims' fear of Western hegemony. In return for the Christian to accept Lebanon's "Arab face," the Muslim side agreed to recognize the independence and legitimacy of the Lebanese state in its 1920 boundaries and to renounce aspirations for union with Syria. [xii]

With hindsight, the pact may be assessed as the least bad political option that could be reached at this time. However, as mentioned earlier, this pact has led to a development of the governmental structure that doesn't lead to political construction and development but rather to mere survival.

4. Change in leadership or systemic change?

The issue at stake is very much related to the legitimacy that could be given to the Lebanese political power. In order to tackle this issue, a basic approach to these terms is a must.

The concept of political power is very vague and might be difficult to find a set definition for it; the basic approach could be "a power exercised in a political community for the attainment of the ends that pertain to the community." [xiii] In order to be political, power inherently requires legitimacy. When the power is fully adapted to the community, only then this power can be considered a political power and therefore, a legitimate power. [xiv] While it is possible to legitimize a power that is divided into a wide variety of sects, it cannot be denied that such power is not fully adapted to the community, but simply divided between the different communities.

Perhaps, the issue in this case is that there cannot be such a thing as "a community" for the different sects that conform the Lebanese society. Perry Anderson[xv] states that in 2005, the Saudi Crown reintroduced the millionaire Rafik Hariri into the Lebanese politics getting him to become prime minister. In return, Hariri had to allow the Salafists to preach in Sunni villages and cities, up to the point that his son, Saad, does not manage to control the Sunni community any longer. How is it possible to avoid such a widespread division of sects in a region where politics of influence are played by every minimally significant power?

Furthermore, in order to be legitimate, power must safeguard the political community. However, going deeper into the matter, it is essential that a legitimate power transcends the simple function of safeguarding and assumes the responsibility of maintaining the development of the community. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, in this case there might be no such thing as a community; therefore, the capacity of the political power in this specific case, legitimacy might be link to the idea of leading the project of building and developing such idea of community under one united political entity. Possibly, the key to achieve a sense of community might be the abolition of confession-based politics however... Is it possible?

Additionally, another reason for which I do not believe that there is a full politicization of the state is because it has still not transitioned from power, understood as force, into power understood as order. The mere presence of an Iranian backed militia in the country which does have a B degree of influence on the political decisions doesn't allow for such an important change to happen. In the theory, the state should recover the full control of military power however, the reality is that Lebanon does need the military efforts of the Shiite militia.

Finally, a last way to understand the legitimacy of the power can be through acceptance. Legitimacy consists on the consent given to the power, which implies the disposition to obey of the community, and the acceptance of the capacity to force, of the power[xvi]. Until now there has been acceptance. However, being these protests the biggest ones seen since the end of the civil war, it is an important factor to bear in mind. It might be that these protests delegitimize the political power, or they might simply reflect the euphoric hit that many of these events tend to cause before disappearing.

5. Conclusion

After three months since the beginning of the protests, it seems that steps have been taken backwards rather than forwards. Could Hariri's resignation mean a step forward towards the construction of the community and the abolition of the sectarian division?

The key idea is the nature of the 1943 agreement. The Pact's core idea was to help overcome any philosophical divisions between the two main communities, the Christian and the Sunni. The Christians were not willing to accept a united Arab Nation with Syria, and the Muslims were not willing to be fully ruled by the Christians. However, 80 years later, the importance of confessionalism in the political structure is still there, it has not diminished.

To sum up, there are two additional ideas to be emphasised. One is that Lebanon was created in order to remain a non-Muslim state in an Arab world, the second one is that the principal reason for stating that the political powers in the Arab world have so little legitimacy is because of the intrusion of other regional powers in the nation's construction of a community and the persistent war that is being fought between the Sunni and the Shiite in the region in[i] B. Alterman, J. (2019). Lebanon's Government Collapses. Retrieved 16 December 2019, from

[ii] B. Alterman, J. (2019). Lebanon's Government Collapses. Retrieved 16 December 2019, from

[iii] B. Alterman, J. (2019). Lebanon's Government Collapses. Retrieved 16 December 2019, from

[iv] B. Alterman, J. (2019). Lebanon's Government Collapses. Retrieved 16 December 2019, from

[v] CIA. (2019). World Factbook (p. Lebanese government). USED.

[vi] CIA. (2019). World Factbook (p. Lebanese government). USED.

[vii] Hourani, A. (2013). A history of the Arab peoples (p.). London: Faber and Faber.

[viii] el-Khazen, F. (1991). The Common Pact of National Identities: The Making and Politics of the 1943 National Pact [Ebook] (1st ed., pp. 7, 13, 14, 49, 52,). Oxford: Centre for Lebanese Studies, Oxford. Retrieved from

[ix] Taber, A. (2016). The lines that bind (1st ed.). Washington: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

[x] el-Khazen, F. (1991). The Common Pact of National Identities: The Making and Politics of the 1943 National Pact [Ebook] (1st ed., pp. 7, 13, 14, 49, 52,). Oxford: Centre for Lebanese Studies, Oxford. Retrieved from

[xi] el-Khazen, F. (1991). The Common Pact of National Identities: The Making and Politics of the 1943 National Pact [Ebook] (1st ed., pp. 7, 13, 14, 49, 52,). Oxford: Centre for Lebanese Studies, Oxford. Retrieved from

[xii] Thomas Collelo, ed. Lebanon: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1987.

[xiii] Zemsky, B. (2019). 2000 [Blog]

[xiv] Cruz Prados, A. (2000). Ethos and Polis (2nd ed., pp. 377-400). Pamplona: EUNSA.

[xv] Mourad, S. The Mosaic of Islam: A Conversation with Perry Anderson (1st ed., pp. 81-82). Madrid: Siglo XXI de España Editores, S. A., 2018.

[xvi] Jarvis Thomson, J. (1990). The Realm of Rights (1st ed., p. 359). Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Gold mining and oil transport pollute Amazonian rivers

Not only are fires negatively affecting the Amazon, which is undergoing an accelerated reduction in forest mass, but increased activity, driven by deforestation itself - which in turn encourages illegal mining and more fuel transport - increases pollution of the Amazon River and other waterways in the countries that are part of the region. The use of mercury in gold mining is an additional serious problem for the communities living in the basin.

![Sunset on the Amazon River, Brazil [Pixabay] [Pixabay]. Sunset on the Amazon River, Brazil [Pixabay] [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/amazonas-blog.jpg)

▲ Sunset on the Amazon River, Brazil [Pixabay].

article / Ramón Barba

The increase in illegal mining in the Amazon region, in countries such as Colombia and Peru, and especially in Venezuela, has increased river pollution throughout the basin. Pollution is also aggravated by the transport of oil, which generates crude oil leaks, and by the discharge of wastewater linked to increased human activity, which in turn is related to increasing deforestation.

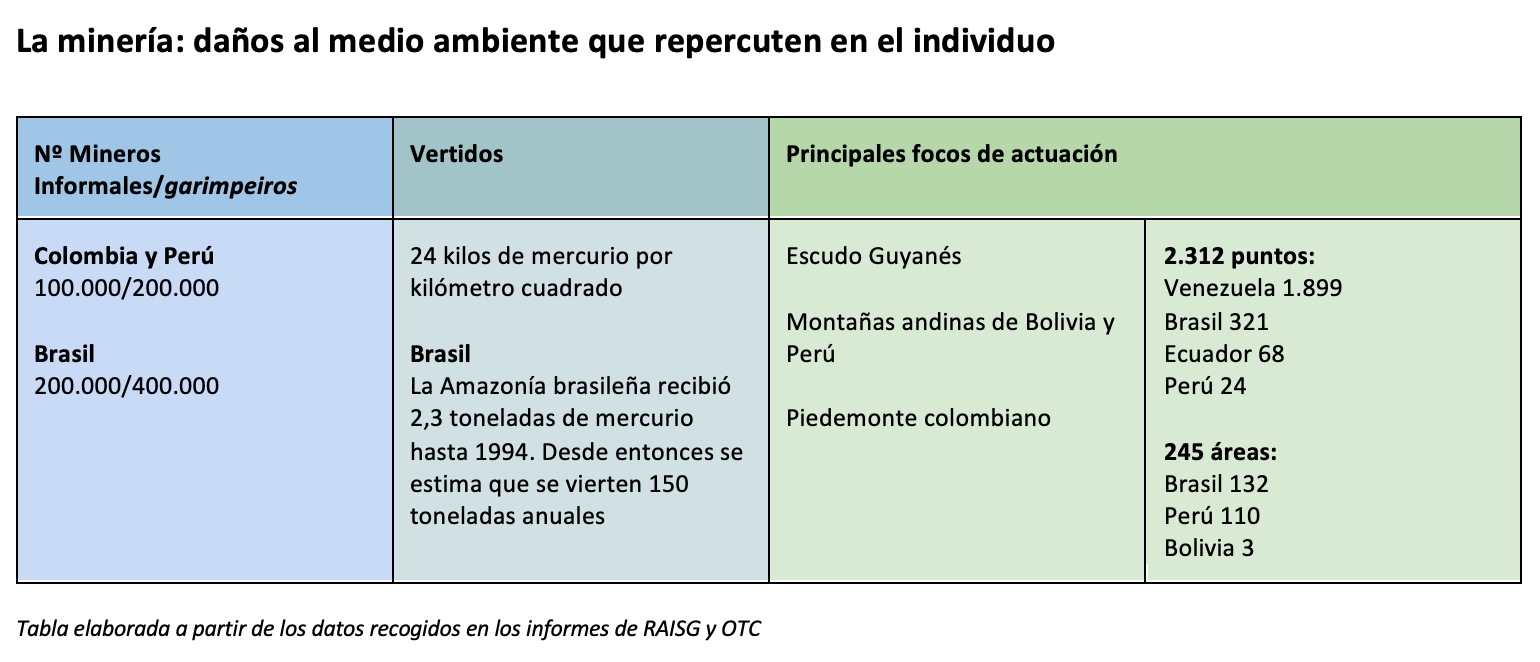

Illegal mining has spread especially in the last two decades, linked to the increase in the price of minerals. Despite the general fall in the price of raw materials since 2014, the quotation has remained high in the case of gold, because as a safe haven value it resists the global economic slowdown. Obtaining gold requires the manipulation of mercury to extract and separate it from the rocks or stones in which it is found. It is estimated that illegal mining activity discharges an average of 24 kilos of mercury per square kilometer. As the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) points out in its report Regional Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis of the Amazon Basin of 2018, it is estimated that the Brazilian Amazon alone received 2,300 tons of mercury until 1994 and then has registered volumes around 150 tons per year.

ACTO indicates that mining is located especially in the Guiana Shield, in the Andean zones of Peru and Bolivia, and in the Colombian piedmont. Information gathered by this organization estimates that between 100,000 and 200,000 people are involved in this activity in Colombia and Peru, a figure that doubles in the case of Brazil.

For its part, the network Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada (RAISG), in its study La Amazonía Saqueada, of late 2018, notes that the area in which illegal mining occurs "is on the rise", especially in Venezuela, where "reports change drastically from year to year". The RAISG computes 2,312 points in the Amazon region where there is illegal mining activity, of which 1,899 correspond to Venezuela.

According to RAISG's report , mining exploitation gives a double functionality to rivers, as they are used for the introduction of machinery and for the disposal of minerals. This has serious environmental effects (soil erosion, contamination of water and hydrological resources, extinction of aquatic flora and fauna, atmospheric impacts...), as well as serious consequences for the health of indigenous peoples, as mercury contamination of rivers affects fish and other living beings that move in the river environment. Given that the main per diem expenses of indigenous peoples is fish, the ingestion of high levels of mercury ends up damaging the health of the populations (cases of loss of vision, heart disease, damage to the central nervous, cognitive or motor system, among others).

Another aspect of mining activity is that it tends to lead to land appropriation and incursion into protected natural areas in the Amazon, increasing deforestation and reducing biodiversity. The Tapajós and Xingú areas in Brazil, together with the Guiana Shield, are the areas most affected by deforestation, according to RAISG. According to programs of study , this organization indicates that deforestation due to gold mining has accelerated in the last twenty years, from 377 km2 deforestation between 2001-2007, to 1,303 km2 deforestation between 2007-2013. In Peru, it is worth noting the case of department Madre de Dios, where 1,320 hectares were deforested between 2017 and 2018.

Other causes of contamination

In addition to illegal mining, other processes also pollute rivers, such as hydrocarbon extraction activities, wastewater discharge and river transport, as warned by ACTO, an organization that groups the eight countries with territory in the Amazon region: Brazil, Colombia, Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela, Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador.

Hydrocarbon contamination. The status affects the five countries to the west of the Basin (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Guyana and Brazil), Bolivia being a potential candidate as it has large untapped gas reserves in the area. Contamination in this case comes from the transport of oil by river from the extraction points to the refineries. This has important environmental and socioeconomic consequences, such as soil degradation and air pollution, which also implies loss of flora and fauna, as well as hydrobiological resources, affecting biodiversity and species migration. In the socioeconomic field, these problems translate into increased operational costs, the displacement of indigenous people, an increase in diseases and the emergence of conflicts.

Pollution from domestic, commercial and industrial wastewater. Despite the large amount of water available in the countries of the Amazon basin, the level of sanitation does not exceed 60%. As a consequence, rivers become vectors of disease in many rural communities, as sanitation is lower in these communities. data , which has not been updated, speaks of urban and domestic waste of 1.7 million tons per liter and 600 liters per second in 2007. At the same time, it is important to take into account the damage caused by agroindustrial activities in river courses, since the large number of insects and microorganisms issue implies an abundant use of pesticides, herbicides and fungicides. Among the environmental and social problems caused by this activity are the emission of greenhouse gases, the deterioration of aquatic ecosystems, eutrophication and pollution by agrochemicals, and the loss of wages and increase in water treatment costs.

Pollution from river transport. The Amazon region has about 24,000 km of navigable rivers, which are the main means of communication. Some 50 million tons of cargo were transported on the Amazon at the beginning of the decade just ended. In addition to fuel leaks, the activity produces a dragging of sludge that is not dredged periodically, as well as contamination of riverbanks and beaches, which damages the Economics and tourism.

Impact on indigenous communities

For many indigenous peoples, as is the case in Colombia, gold is a sacred mineral because it represents the sun on earth. They consider that the extraction of this mineral implies the loss of life in the territory and in order to extract it the shamans of the area must "ask permission" through a series of ceremonies; to do so without the granted permission implies negative consequences, hence the indigenous populations associate the improper extraction of gold with illness and death. An example of this is the area of the Aaporis River, also considered sacred, where Yanomami leader Davi Kopenawa speaks of the xawara wakémi (the smoke epidemic), derived from the burning of gold and which is, according to him, the cause of death of some inhabitants of the area.

However, members of indigenous communities also engage in artisanal mining, either because they reject the tradition of entrance in the face of the economic benefits of illegal extraction, or because they are forced into this occupation by the lack of opportunities. The latter occurs in the Peruvian communal reservation of Amarakaeri, which is very affected by extractive activity, where its inhabitants have been forced to practice artisanal mining, pressured by their subsistence needs and by external mining interests that end up exploiting them.

Uncontrolled mining, on the other hand, has a negative impact on the environment in which indigenous people live. In the Ecuadorian province of Zamora Chinchipie, for example, a mega project open-pit mining operation was carried out, the impact of which has involved deforestation in the area of 1,307 hectares between 2009 and 2017.

It is worth highlighting the fact that mining not only implies an attack against certain indigenous cultural aspects, but also a serious attack against their human rights in that, despite being peoples living in voluntary isolation, mining companies interfere in these reserves and force displacements and uprooting. This status is especially critical in Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru, countries in which there is a "gray zone" between legality and illegality in artisanal mining, increasing the Degree impact on indigenous areas. At the same time, it is worth mentioning the repressive activity of the states in the destruction of dredges and rafts, which leads to a violent response from those affected, as occurred in the Humaita revolt in Brazil.

Indigenous life has also been affected by the presence in these territories of guerrilla or paramilitary groups, as well as organized crime groups. In Colombia, armed groups have taken advantage of mining to finance their activities, which they develop in areas with high levels of poverty and difficult access for the Government. Between 2017 and 2018 there was a 6% increase in this activity, in places where coca can also be grown, whose production has likewise increased in recent years. The OECD 's 2016 Due Diligence in the Colombian Gold Supply Chain report indicates that the FARC, ELN and criminal gangs began their mining activity in the 1980s and increased it in the 1990s as a result of the rising price of gold and the increased difficulty of obtaining stable drug revenues. In 2012, the FARC and ELN had a presence in 40% of Colombia's 489 mining municipalities. Recently, ELN presence has been witnessed in illegal mining in Venezuela, especially in the state of Bolivar, to which FARC dissidents sheltered in Venezuelan territory could be added.

[Eric Rutkow, The Longest Line on the Map: The United States, the Pan-American Highway and the Quest to Link the Americas. Scribner. New York, 2019. 438 p.]

REVIEW / Marcelina Kropiwnicka

Though the title tries to convince the reader that they will merely be exploring the build-up to the largest link between the United States of America and its southern neighbours, The Longest Line on the Map: The United States, the Pan-American Highway and the Quest to Link the Americas covers much more. The book is written in more of a novel-fashion than a textbook-fashion. Author Eric Rutkow, rather than simply discussing the nitty-gritty development of the highway alone, is able to cover historical events from political battles in the homeland of the US to economic hardships encountered among the partner countries. Divided into three main blocks, the book chronologically introduces the events that took place during the Pan-American Highway's construction, beginning with the dream that a railway would connect the two hemispheres.

Though the title tries to convince the reader that they will merely be exploring the build-up to the largest link between the United States of America and its southern neighbours, The Longest Line on the Map: The United States, the Pan-American Highway and the Quest to Link the Americas covers much more. The book is written in more of a novel-fashion than a textbook-fashion. Author Eric Rutkow, rather than simply discussing the nitty-gritty development of the highway alone, is able to cover historical events from political battles in the homeland of the US to economic hardships encountered among the partner countries. Divided into three main blocks, the book chronologically introduces the events that took place during the Pan-American Highway's construction, beginning with the dream that a railway would connect the two hemispheres.

With the New World just barely beginning to grasp its potential, writer Hinton Rowan Helper's first-hand experience of traveling from the United States to Argentina in the mid-1800s made him come to the realization that there must be an alternative method of traveling between the two countries. After enduring the long voyage, he came to the conclusion, "Why not by rail?" The first quarter of the book hence explains the early attempts made towards linking the wide span between North America and Southern Argentina through the use of a railroad. Thus, when in 1890 the Intercontinental Railway Commission was created, the idea of a Pan-American railway began to flourish and preliminary work began.

The idea was passed on from one indefatigable supporter to another, keeping in mind the cooperative aim of pan-Americanism and the potential for US economic expansion. Yet still by the early 1900s, over half of the projected length of the railway remained unassembled. Despite multiple attempts and investment in building and rebuilding the rail (mainly due to logistical purposes), the project came to a final halt with the realisation that the Pan-American Railway was beginning to look like what it was: an unfeasible dream. President Theodore Roosevelt had concluded similarly in 1905, when he gave preference to developing the Panama Canal, regulating the rules of the railway and building the US Navy. In the subsequent and comparatively short chapter of the book, Rutkow introduces the era when automobiles and bicycles were on the rise, causing a demand for the increased construction of roads and exhaustive efforts to build decent thoroughfare within the US. Also made note of in the book was the diverging attention from the rail as a result of the outbreak of the First World War. These events combined would ultimately cease continuation of the railway's assembly.

The second half of the book is dedicated to the continuation of the dream of connecting the two spheres using a different method: the building of the Pan-American Highway. Although only a sister to the railway project, the two ideas arise from the same ideal. The new project seemed especially tangible due to the growth of the 'motoring generation' and the strengthened advocacy of Pan-Americanism. The belief was that the highway would foster "closer and more harmonious relations" among the nations in the Americas. Nevertheless, the highway remains unfinished due to a mere 50-mile wide gap, known as the Darien Gap, located between Panama and Colombia ("mere" considering the highway today stretches more than 20,000 miles, connecting Alaska to the southern tip of Argentina).

The most engaging part of the book emerges in the last chapter, when Rutkow attempts at connecting the missing link between the two worlds, but isn't able to, which reminds us that the road remains unfinished. The chapter, which is committed to the Darien Gap, is able to give light to the idea that once, the two spheres had a dream of connecting, contrasting to what we see today with the pressure of erecting walls along the southern US border. Though the dream continues to overcome the gap and finish the road, a new challenge had finally emerged: Panama had changed its policy and refused to finish the pavement.

As for such a well-researched book of one of the largest projects on the American continent, there's a peculiar laxity: the coverage on South America is far less complete in comparison to all the focus that the United States' government efforts to organizing and funding the link received. In terms of critiquing the book as a literary piece, not every quotation within the book would be considered absolutely necessary to telling the story. Ironically there's a certain scarcity when it comes to describing the road itself or its surrounding environment. Perhaps the author makes up for this blunder with his meticulous choosing of maps and images to provide the reader with a context of the environment and era in which the dream was being pursued.

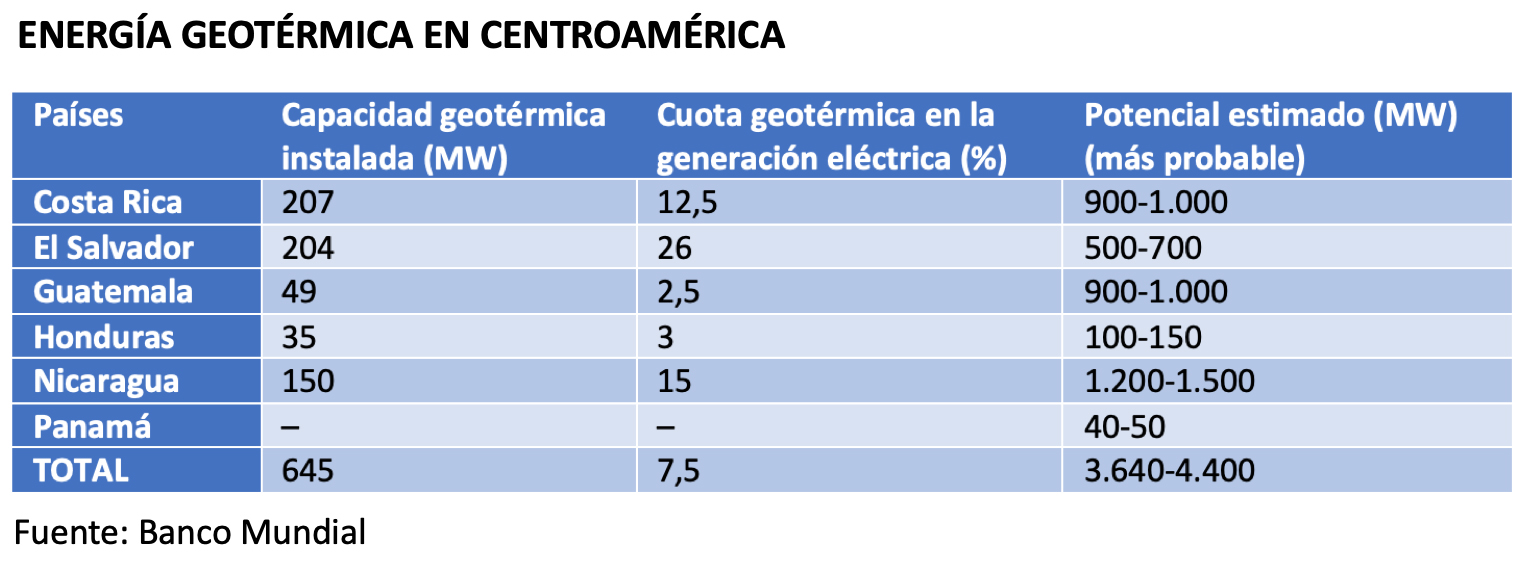

Geothermal energy already accounts for 7.5% of the Central American electricity mix, with installed capacity still far below the estimated potential.

Central America's volcanic activity and tectonic movements offer optimal conditions for the region's small countries to take advantage of an alternative energy source to imported hydrocarbons or an ever more polluting coal. At the moment, the installed capacity -largest in Costa Rica and El Salvador- is barely 15% of the most likely estimated potential.

![San Jacinto-Tizate geothermal power plant in Nicaragua [Polaris Energy Nicaragua S. A.] [Polaris Energy Nicaragua S. A.]. San Jacinto-Tizate geothermal power plant in Nicaragua [Polaris Energy Nicaragua S. A.] [Polaris Energy Nicaragua S. A.].](/documents/10174/16849987/geotermica-blog.jpg)

▲ San Jacinto-Tizate geothermal plant in Nicaragua [Polaris Energy Nicaragua S. A.] [Polaris Energy Nicaragua S. A.].

article / Alexia Cosmello

Central America currently has an installed geothermal capacity of 645 megawatts (MW), far from the potential attributed to the region. This may reach, in the highest band of estimates, almost 14,000 MW, although the most likely estimates speak of around 4,000 MW, which implies a current utilization of approximately 15%, according to data of the World Bank published in 2018.

The energy obtained constitutes 7.5% of the total electricity generation in Central American countries: a not insignificant figure, but one that still needs to grow. Forecasts point to an expanding sector, although attracting the necessary foreign investment has so far been limited by the risks inherent in this industry and national legal frameworks.

Geothermal energy is a clean, renewable energy that does not depend on external factors. It consists of harnessing the heat of the earth's interior - high temperature resources in the form of hot subway fluids - for electrical and thermal generation (heating and domestic hot water). It is governed by the magmatic movement of the earth, which is why it is a scarce resource and limited to certain regions with a significant concentration of volcanic activity or tectonic movement.

Latin America

These characteristics of the American isthmus are also shared by Mexico, where the geothermal sector began to develop in the 1970s and has reached an installed capacity of 957 MW. The friction of the tectonic plates along the South American and eastern Caribbean coast also gives these subregions an energy potential, although less than that of Central America; its exploitation, in any case, is small (only Chile, with 48 MW installed, has really begun to exploit it). The total geothermal potential of Latin America could be between 22 GW and 55 GW, a particularly imprecise range given the few explorations carried out. Installed capacity is close to 1,700 MW.

The World Bank estimates that over the next decade, Latin America would need an investment of between US$2.4 billion and US$3.1 billion to develop various projects, which would add a combined generation of some 776 MW, half of which would correspond to Central America.

Attracting private capital is not easy, considering that since the 1990s the Latin American geothermal sector has had less than US$1 billion in private investment. Financing difficulties are partly related to the very nature of the activity, as it requires a high initial investment, which is high risk because exploration is laborious and it takes time to reach the energy production stage. Other aspects that have made it less attractive have been the policies and regulatory frameworks of the countries themselves and their deficiencies in the local and institutional management .

Geothermal energy, in any case, should be a priority for countries with high potential such as Central America, given that, as the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) points out, it constitutes a low-cost electricity generation source and also stimulates low-carbon economic growth. For this reason this organization has order to the governments of the Central American region to adopt policies that favor the use of this valuable resource , and to develop legal and regulatory frameworks that promote them.

The World Bank and some countries with particular technological expertise are involved in international promotion and advice. Thus, Germany is carrying out since 2016 a program of development of geothermal potential under the German Climate Technology Initiative (DKTI). The project cooperates with the development Geothermal Fund (GDF), implemented by the German development bank KfW, and the Central American Geothermal Resource Identification Program, supported by the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR). goal The initiative is also supported by the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ), which has organized technical courses, together with business LaGeo, located in El Salvador, for geothermal plant operators, teachers and researchers at subject, with the aim of achieving a better management of the installations and a more efficient development of the energy projects.

By country

Although Central American countries have shown a high dependence on imported hydrocarbons as energy source , in terms of electricity generation the subregion has achieved an important development of renewable alternatives, put at the service of all members of the Central American Integration System (SICA) through the Electrical Interconnection System for Central American Countries (SIEPAC). The executive director of the administrative office General of SICA, Werner Vargas, highlighted at the beginning of 2019 that 73.9% of the electricity produced at the regional level is generated with renewable sources.

However, he indicated that in order to cope with the growing electricity demand, which between 2000 and 2013 increased by 70%, the region needs to make greater use of its geothermal capacities. Greater integration of geothermal energy would save more than 10 million tons of CO2 emissions per year.

The share of geothermal energy in the electricity mix varies from country to country. The highest share corresponds to El Salvador (26%), Nicaragua (15%) and Costa Rica (12.5%), while the share is small in Honduras (3%) and Guatemala (2.5%).

In Costa Rica, the Costa Rican Electricity Institute (ICE) delivered last July the Las Pailas II geothermal plant, in the province of Guanacaste, at a total cost of US$366 million. The plant will contribute a maximum of 55 MW to the electric network , so that when it is fully operational it will raise the total installed capacity in the country from 207 MW to 262 MW.

Costa Rica is followed by El Salvador in electricity generation from geothermal energy. The national leader in production is business LaGeo, manager of almost all of the 204 MW installed in the country. This business has two plants, one in Ahuachapá, which produces 95 MW, and the other in Usulután, with a production of 105 MW. With lower electricity consumption than Costa Rica, El Salvador is the Central American country with the highest weight of geothermal generation in its electricity mix, 26%, double that of Costa Rica.

Nicaragua has an installed capacity of 150 MW, thanks to the geothermal interest of the Pacific volcanic mountain range. However, production levels are clearly below, although they account for 15% of the country's electricity generation. Among the geothermal projects, the San Jaciento-Tizate and Momotombo projects are already being exploited. The first one, exploited by business Polaris Energy, was built in 2005 with the initial intention of producing 71 MW, to reach 200 MW by the end of this decade; however, it is currently producing 60 MW. The second, controlled by business ORMAT and the participation of ENEL, was promoted in 1989 with a capacity of 70 MW, although since 2013 it has been producing 20 MW.

Guatemala is slightly behind, with an installed capacity of 49 MW, followed by Honduras, with 35 MW. Both countries recognize the interest of geothermal exploitation, but have lagged behind in promoting it. And yet the Guatemalan government's ownprograms of study highlights the profitability of geothermal resources, whose production cost is US$1 per MW/hour, compared to US$13.8 in the case of hydroelectric power or 60.94 percent for coal.

Brazil's congress approves ratification of agreement Technology Safeguards signed by Trump and Bolsonaro

With the reactivation of its Alcantara launch centre, the best located in the world due to its proximity to the Equator, the Brazilian space industry expects to reach a turnover of 10 billion dollars a year from 2040, with control of at least 1% of the global sector, especially in the area space launch sector. Jair Bolsonaro's government has agreed to guarantee technological confidentiality to the US, reaching a agreement that Washington had already tried unsuccessfully before the Workers' Party came to power.

![area space launch facility at the Brazilian Alcantara space centre [AEB]. area space launch facility at the Brazilian Alcantara space centre [AEB].](/documents/10174/16849987/alcantara-blog.jpg)

▲ area space launch site of the Brazilian space centre of Alcantara [AEB].

article / Alejandro J. Alfonso [English version].

Brazil wants to be part of the new space age, in which private initiative, especially from the United States, will play a major role, alongside the traditional role of the national agencies of the major powers. With the agreement Technology Safeguards, signed last March by Presidents Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, rockets, spacecraft and satellites equipped with US technology can be launched at the strategic Alcântara base.

The guarantee of technological confidentiality - access to certain parts of the base will only be authorised to staff from the US, although jurisdiction will remain with the Brazilian Air Force - will mean that Alcántara will no longer have to negotiate contracts with only 20% of the world market, as has been the case until now, something that hindered the base's economic viability. However, the agreement also has a limiting aspect, as it only authorises Brazil to launch national or foreign rockets and aircraft that contain US-developed technological parts.

The new political context in Brazil meant that the agreement was ratified without problems on 22 October by the Chamber of Deputies and on 12 November by the Senate, a very different status to the one experienced in 2000, when congress blocked a similar agreement promoted by President Fernando Henrique Cardoso. The subsequent arrival of the Workers' Party to power, with the presidencies of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff, cooled relations between the two countries and Washington temporarily put aside its interest in Alcántara.

Brazil's space aspirations go back a long way; its aerospace industry is the largest in Latin America. In the 1960s it developed a first launch base, Barrera do Inferno, near Natal. In 1994 the military parent of research was transformed into the civilian Brazilian Space Agency (AEB). In addition to development of satellites, AEB launched its first rocket in 2004. In 2006 a Brazilian astronaut joined the International Space Station, of which Brazil is partner.

The Alcántara launch centre is located in Maranhão, a state in northeastern Brazil. Alcántara is a small colonial town located 100 kilometres from the state capital São Luís. The town has 22,000 inhabitants and has access to the sea. The launch site was built during the 1980s and covers an area of 620 square kilometres. In addition, the launch base is located 2.3 Degrees south of the equator, which makes it an ideal location for launching satellites into geostationary orbit. The unique geographical conditions of the launch site attract companies interested in launching small to medium-sized satellites, typically used for communications or surveillance satellites. Unfortunately, the institution suffered a bad reputation when operations were briefly halted due to a failed launch in 2003, resulting in the death of 21 technicians and the destruction of some of the facilities. In 2002 the Agency

The US is interested in Alcantara because of its strategic location. As mentioned above, the launch site is located 2.3 Degrees south of the equator, which allows US rockets to save up to 30 per cent in fuel consumption compared to launches from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Also, due to its proximity to the equator, the drag to reach orbit is lower than Cape Canaveral, which means that companies can increase the weight of the rocket or the cargo it carries without adding additional fuel. This location therefore offers US companies the same advantages enjoyed by their European counterparts who use a launch site in French Guiana, located nearby, north of the equator. The agreement Technology Safeguards signed between Presidents Bolsonaro and Trump in March aims to attract these US companies by assuring them that US companies that do use the Alcantara facility will have the necessary protection and safeguards in place so that their technology is not stolen or copied by Brazilian operators or engineers.

The Brazilian government is clearly interested in the Americans using the Alcantara site. The global space industry is worth approximately $300 billion, and Brazil, which still has a space agency at development, could use the funds from leasing the launch site to further develop its space capabilities. The Brazilian Space Agency has been underfunded for many years, so additional revenues are particularly desirable. In addition, Brazilian officials have speculated that investment in the launch site will bring further investment in the Alcantara region in general, improving the quality of life at area. For example, the Kourou base in French Guiana generates 15% of the French overseas territory's GDP, providing employment directly or indirectly to 9,000 people. In conclusion, the Bolsonaro government hopes that this agreement will deepen the relationship with the US, and that it will also provide the monetary means to invest in the launch site and its surroundings, and invest in the Brazilian Space Agency.

However, this agreement has also been criticised. In 2000, President Cardoso's government attempted to sign a similar agreement with the George W. Bush administration, which was ultimately blocked by the Brazilian congress for fear that Brazil would cede its sovereignty to the US. These same fears are still present today. Former Brazilian Foreign Minister Samuel Pinheiro Guimarães Nieto declared that the US is seeking to establish a military base in Brazil, thus damaging the sovereignty of the Brazilian people. Criticism is also directed at essay of agreement itself, which states that the money the Brazilian government earns from the US use of the launch site cannot be invested in rockets from development exclusively Brazilian, but can be invested in other areas related to the Brazilian Space Agency.

In addition to arguments about the integrity of Brazilian sovereignty, there is also a defence of the Quilombolas, descendants of Brazilian slaves who escaped their masters, who were displaced from their coastal lands when the base was built. The government is currently proposing to increase the size of the Alcantara launch site by 12,000 hectares, and Quilombo communities fear that they will once again be forced to move, causing them further impoverishment. This has been the subject of discussion on both the Brazilian congress and the UScongress , with Democratic House representatives introducing a resolution calling on the Bolsonaro government to respect the rights of the Quilombolas.

The agreement Technology Safeguards is a primarily commercial agreement in order to attract more US companies to Brazil for the Alcantara site, which would save these companies money due to the ideal location of the launch site, while giving them the opportunity to invest in the Brazilian space programme. However, due to the controversies mentioned above, some may consider this as a unilateral agreement where only US interests prevail, while the Brazilian government and people lose sovereignty over a strategic site. Nevertheless, it should be noted that Brazil has traditionally developed an important aeronautical industry (Embraer, recently bought by Boeing, is an excellent example) and the Alcantara base provides the opportunity for Brazil to leap into the new space age.

For decades, the U.S. closed its doors to Mexican avocados; Today it needs it to meet its growing demand

2019 will see record imports of Mexican avocados into the United States: almost 90% of the one million tons of avocados consumed by Americans will come from the neighboring country, which leads the world in production. After being banned for decades in the U.S. – alleging phytosanitary issues, especially invoked by California producers – the creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement opened the doors of the U.S. market to this Mexican product, first with reservations and since 2007 without restrictions. The arrival of Trump to the presidency marked a decline in imports, but since then they have not stopped rising.

▲ Interest in healthy food has led to an increase in avocado consumption around the world

article / Silvia Goya

Social trends such as veganism or "real fooding" have increased the global production of avocados, a fruit valued for its healthy fat and vitamin content, which enlivens a multitude of dishes. In the United States, moreover, the food tradition of millions of Hispanics – the avocado is born from a tree native to Central and South America (Persea americana) – has encouraged the consumption of a product that, like few others, marks relations between the United States and Mexico.

The department The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) predicts that in order to meet the growing national consumption of avocados (which has multiplied by 5.4 since 2000, from 226,000 tons to 1.2 million in 2018), in 2019 the country will have to increase its imports significantly, so that they will constitute 87% to 93% of the country's economy. availability of product. This will mean an increase in imports from Mexico, which in 2018 already contributed 87% of avocados from abroad. This need for imports is due in part to production problems in California, the state with the highest production in the US (around 80%), well ahead of the second, Florida, and a major litigator in the past to prevent the production of the skill of the Mexican avocado.

Donald Trump's first year in the White House saw a slight decrease in Mexican avocado imports, which in 2017 fell to 774,626 tons. However, in 2018 a new record was reached, with 904,205 tons, with an increase of 17%, in a context of non-materialization of the trade threats launched by the Trump Administration, which finally agreed to the renewal of the free trade agreement with Mexico and Canada. Last year, imports from Mexico accounted for 87% of total avocado purchases abroad; the rest, up to 1.04 million tonnes, corresponded to those from Peru (8%), Chile (2.5%) and the Dominican Republic (2.5%).

History of a veto

The B The rise in avocado sales in the U.S. has attracted the attention of drug cartels, which have clashed to control the business in some Mexican states such as Michoacán – the major producer of avocados, especially of the Hass variety, which is the most commercialized – giving rise to a "new drug trafficking." However, the history of controversy between the two countries over this berry goes back a long way. It was in 1914 that the then U.S. Secretary of Agriculture signed a notice A quarantine decree declaring the need to ban the import of avocado seeds from Mexico due to a weevil that the seed carried. In 1919 the "Quarantine of Nurseries, Plants and Seeds" was enacted. That framework was in place for decades.

During the 1970s, the discussion of the entrance of Mexican avocados in the U.S. market remained in the political spotlight due to the insistence of officials from Mexico's Plant Health Service. Investigations in several Mexican avocado-producing states, however, found weevils in some of the seeds, which did not allow the regulatory policy of the Animal and Plant Inspection Service (APHIS) to be changed. department U.S. Department of Agriculture. For this reason, in 1976 the USDA, in a letter addressed to its Mexican counterpart, stated that it should continue "as in the past, against the issuance of permits for the importation of avocados from Mexico."

Following these events, U.S. policy on avocados from neighboring China remained restrictive until trade liberalization and harmonization of sanitary and phytosanitary measures began to change the context in which governments examined plant health and import issues. For most of the twentieth century, the policy of protection had been to deny access to products that could harbor pests; In the last decade, however, the rules began to change.

The creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 and the World Trade Organization in 1995 paved the way for new Mexican requests for access to the U.S. avocado market. Although the goal One of the main aspects of NAFTA was the elimination of tariffs by 2004, and it also provided for the harmonization of sanitary and phytosanitary measures among trading partners. Nonetheless, this free trade agreement explicitly recognizes that each country can establish regulations to protect human, animal, and plant life and health, so when the risk of pest infestation is high, the country has legitimacy to put restrictions on trade.

With the implementation of NAFTA in 1994, the U.S. government came under increased pressure to facilitate the importation of agricultural products from Mexico, including avocados. This led to a shift in USDA's phytosanitary policy toward a new "mitigation or technological solutions" policy. APHIS is the branch of government in charge of implementing the phytosanitary provisions of NAFTA in the case of the United States. This body considered that fruit flies – present in a wide variety of species – could also be found in Mexican avocados, so officials from Mexico's Plant Health Service had the difficult task of proving that this insect was not present in their avocados and that those of the Hass variety were not susceptible to attack by the Mexican fruit fly. Between 1992 and 1994, Mexico submitted two plans for work with their respective investigations. The former was rejected while the latter, despite pressure from the California Avocado Commission (CAC), was accepted.

This second plan called for Mexican avocado access to 19 of the 50 U.S. states during the months of October through February. At the end of June 1995, the USDA issued a proposal of rule which described the conditions under which Hass avocado grown on approved plantations in Michoacán could enter the U.S. It was at the end of 1997 that the USDA published a rule authorizing the importation of these avocados to the United States. This was the first time the USDA used the so-called "approach systems" to manage the risks posed by quarantine pests.

At the end of the second shipping season, in February 1999, Mexico requested the expansion of the programme to increase the issue of U.S. states to which it could export and allow the shipping season to start a month earlier (September) and end a month later (March). In 2001, the USDA met with the Mexican Plant Health Service and agreed to consider expanding the importing states to 31 and import dates from October 15 through April 15. The good relationship established between Presidents George W. Bush and Vicente Fox had a clear influence on this expansive movement.

![Imports in tonnes. In 2018, imports of 1.04 million tonnes (87% from Mexico) [source: USDA] Imports in tonnes. In 2018, imports of 1.04 million tonnes (87% from Mexico) [source: USDA]](/documents/10174/16849987/aguacate-grafico.png)

Imports in tonnes. In 2018, imports of 1.04 million tonnes (87% from Mexico) [source: USDA]

Liberalization