Global interest in this fashionable grain has brought additional income to Andean communities.

The localization of quinoa production, especially in Peru and Bolivia (together they account for almost 80% of world exports), has given these nations an unexpected strategic value. The high protein component of this pseudocereal makes it attractive to countries where food security is a priority.

▲ Quinoa field in the Andes of Bolivia [Michael Hermann-CC].

article / Elisa Teomiro

Quinoa, also known as quinoa (in Latin Chenopodium quinoa), is an ancestral grain that is more than 5,000 years old and was originally cultivated by the pre-Columbian Andean cultures. After the arrival of the Spaniards in America, it was partly displaced by the cereals brought from the peninsula. It does not belong to the grass family but to the family of the chenopodiaceae (spinach, chard or beets); therefore it is more correct to consider it as a pseudocereal.

It forms the basis of the diet of the Andean population of South America, especially in the high Andean areas of Bolivia and Peru (between the two countries they account for approximately 76% of the total quinoa Issue exported in the world, 46% Bolivia and 30% Peru). Today, due to its adaptation to different climates (it survives frost, high temperatures, lack of oxygen in the air, lack of water and high salinity), its production has diversified and more countries are producing it: Ecuador, Venezuela, Colombia, Chile, Argentina, USA and Canada, in the American continent, as well as Great Britain, Denmark, Finland, France, Sweden, Holland, Spain, Australia and the USSR, outside it.

Quinoa has gone from being a perfect unknown, for the majority of the non-American population, to undergoing a spectacular rise in a very short time. One of the reasons for this was the decision made by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) to declare 2013 as the International Year of Quinoa. The FAO wanted to reward the great effort being made by the Andean peoples to conserve the grain in its natural state, as food for current and future generations. The activities carried out during that year made quinoa and its nutritional properties known to the world.

Price increase

The interest awakened by this grain tripled its price between 2004 and 2013, which curiously generated a discussion about a possible negative impact on the producing populations. Thus, it was alleged that the high demand for this crop by developed countries had turned quinoa into aarticle luxuryarticle " in producing countries, where it already cost more than chicken or rice. It was considered that this status could cause malnutrition in the Andean population, as they could not supplement their scarce per diem expenses with quinoa.

A follow-up on this issue subsequently showed that the quinoa boom was actually helping communities at source. A study by the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the World Trade Organization and the United Nations based in Geneva, conducted over the 2014-2015 period, noted that quinoa consumption by developed countries was improving the livelihoods of small-scale producers; most of them women.

agreement to this study, rising prices between 2004-2013 caused both producers and consumers in the producing regions to benefit financially from trade. Thus, there was a 46% increase in their welfare in this period, measured through the value of goods and services consumed by households. The report also highlighted how, on the contrary, the 40% drop in the price of quinoa grain, suffered towards the end of 2015, caused a decline in the welfare of rural households (food consumption fell by 10% and wages by 5%). The study reached two clear conclusions: the sustained decline in Peru in quinoa consumption since 2005 was probably due more to changing consumer preferences due to globalization and increased product supply than to changes in grain prices; global quinoa consumption in developed countries undoubtedly contributed to the development resource-poor communities in the altiplano.

Production and trade

There are several reasons why this grain has become so attractive to consumers in Europe and the U.S.A., and increasingly also in China and Japan: its protein content is very high, between 14% and 18%, and they are also proteins of high biological value that would allow it to be a substitute for animal protein (it contains the 10 essential amino acids for human per diem expenses ). This factor, together with its high iron content, makes it an ideal pseudocereal for vegetarians; it does not contain gluten, so it can also be consumed by coeliacs; it has a low glycemic content, which allows its consumption by diabetics; its fiber and unsaturated fatty acid content (mainly linoleic acid) is high, so all those concerned about their health have an option in quinoa. It is also a source of vitamin E and B2 (riboflavin) and is high in calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium and iron. For all these reasons, the FAO considers that its high nutritional value financial aid eradicate hunger and malnutrition.

|

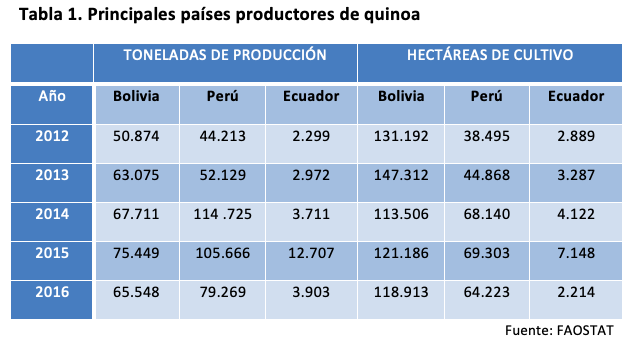

The ranking of quinoa producing countries is headed by Bolivia (its 118,913 hectares of cultivation accounted for 60% of the total area of quinoa sown in the world in 2016), followed by Peru (64,223 hectares, representing 30% of the world area sown) and Ecuador (2,214 hectares) [Table 1]. From 1990 to 2014, the area planted with quinoa increased from 47,585 hectares to 195,342 hectares. The global value of exports increased from US$135.5 million in 2012 to US$321.5 million in 2015.

Regarding the export Issue in tons, Bolivia was the first country during 2012 (more than 25,000 tons), which represented, together with 2013 exports, an income for the country of US$80 million. In the same year, Peruvian quinoa exports exceeded 10,000T which represented an income for the country of US$38 million. In 2014, Peru took over and dominated the market also in 2015 and 2016 [Table 2].

The USA is the main importer of quinoa in the world, with 40%; it is followed by the European Union, with more than 30% of the total (France, Holland, Germany, Great Britain, Italy and Belgium mainly) and then Canada. The average price per kilo of quinoa was US$3.2 in 2012 and US$6.2 in 2014. In 2015 it dropped to 5 dollars. Per capita consumption is logically led by the two main producers: Bolivia consumes 5.2 kilos and Peru 1.8 kilos, followed at a distance by Ecuador, with 332 grams per person.

In non-producing countries, quinoa was first introduced in the organic sector, with consumers concerned about healthier diets, although today it is no longer exclusive to this market. The largest consumer of quinoa per capita worldwide is Canada, with more than 180 grams, followed closely by the Netherlands; France and Australia consume between 120 and 140 grams. In Spain, consumption is still small, at around 30 grams. Global forecasts up to 2025 are that per capita consumption will reach 200 grams (an achievement that Canada is already within reach) and that even countries that traditionally consume rice, such as Japan and South Korea, will also embrace quinoa.

Quinoa production faces future problems in terms of both environmental and market subject . Before its boom in 2013, almost 60 different varieties of the grain were grown in the Andean highlands and almost all quinoa was organic. Today, rampant trade and large-scale production on large farms has reduced biodiversity to fewer than 20 different types.

market research forecasts commissioned by the Trade for Development Center in 2016 on current and future markets for quinoa point to a very likely doubling of the global market in ten years, especially with conventional quinoa produced not only in Peru, but also in Australia, the United States and Canada. The production of organic quinoa, produced by small farmers in the highlands, will remain relatively stable. Market skill will continue to be fierce, so farmers in the altiplano will have to seek measures that will allow them to maintain a niche market with certified organic quinoa, grown using traditional and fair trade methods.