The hydrocarbon field is the central axis of the Gas 2020-2023 Plan of President Alberto Fernández, which subsidizes part of the investment

Activity of YPF, Argentina's state-owned hydrocarbons company [YPF].

ANALYSIS / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa

Argentina is facing a deep economic crisis that is having a severe impact on the standard of living of its citizens. The country, which had managed to emerge with enormous sacrifices from the 2001 corralito, is seeing its leaders committing the same macroeconomic recklessness that led the national Economics to collapse. After a hugely disappointing mandate of Mauricio Macri and his economic "gradualism", the new administration of Alberto Fernandez has inherited a very delicate status , now aggravated by the global and national crisis generated by Covid-19. The public debt already represents almost 100% of the GDP, the Argentine peso is worth less than 90 units per US dollar, while the public deficit persists. Economics remains in recession, accumulating four years of decline. The IMF, which lent nearly $44 billion to Argentina in 2018 in the largest loan in the institution's history, has begun to lose patience with the lack of structural reforms and hints of debt restructuring by the government. In this critical status , Argentines are looking to the development of the unconventional oil industry as a possible way out of the economic crisis. In particular, the Vaca Muerta super field has been the focus of attention of international investors, government and citizens for a decade, being a very promising project not Exempt environmental and technical challenges.

The energy sector in Argentina: a history of fluctuations

The oil sector in Argentina has more than 100 years of history since oil was discovered in the Patagonian desert in 1907. The geographical difficulties of the area -lack of water, distance from Buenos Aires and saline winds of more than 100 km/h- made the project advance very slowly until the outbreak of the First World War. The European conflict interrupted coal imports from England, which up to that date constituted 95% of Argentina's energy consumption. The emergence of oil in the interwar period as a strategic raw subject revalued the sector, which began to receive huge foreign and domestic investments in the 1920's. By 1921 YPF was created, the first state-owned oil business in Latin America, with energy self-sufficiency as its main goal. The country's political upheaval during the so-called Década Infame (1930-43) and the effects of the Great Depression damaged the incipient oil sector. The years of Perón's government saw a timid take-off of the oil industry with the opening of the sector to foreign companies and the construction of the first oil pipelines. In 1958 Arturo Frondizi became President of Argentina and sanctioned the Hydrocarbons Law of 1958, achieving an impressive development of the sector in only 4 years with an immense public and private investment policy that tripled oil production, extended the network of gas pipelines and generalized the access of industry and households to natural gas. The oil regime in Argentina maintained the ownership of the resource in the hands of the state, but allowed the participation of private and foreign companies in the production process.

Since the successful decade of the 1960s in oil subject , the sector entered a period of relative stagnation in parallel with Argentina's chaotic politics and Economics at the time. The 1970s was a complex journey in the desert for YPF, mired in enormous debt and unable to increase production and ensure the longed-for self-sufficiency.

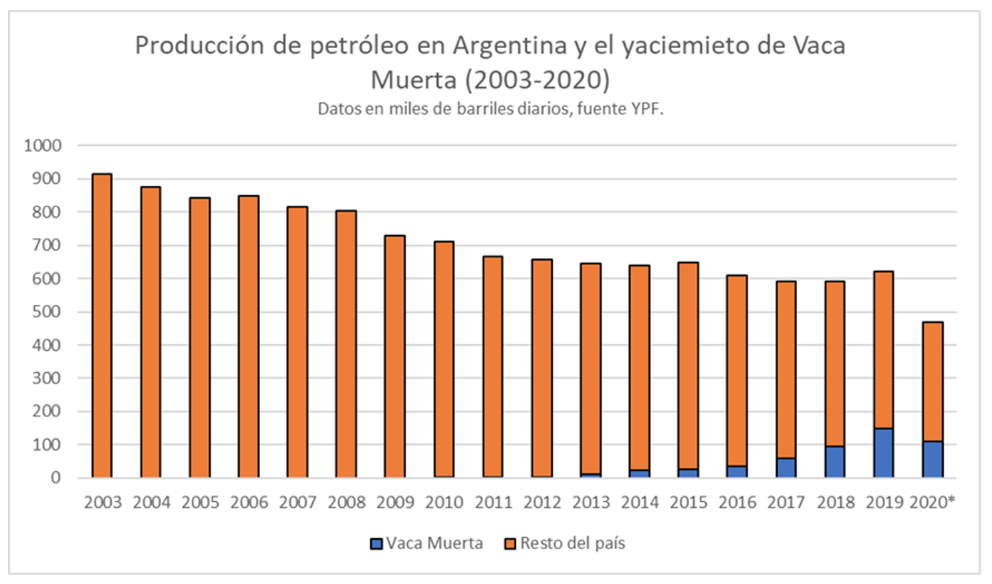

With the so-called Washington Consensus and the arrival of Carlos Menem to the presidency in 1990, YPF was privatized and the state monopoly over the sector was fragmented. By 1998, YPF was fully privatized under the ownership of Repsol, which controlled 97.5% of its capital. It was in the period 1996-2003 when maximum oil production was reached, exporting natural gas to Chile, Brazil and Uruguay, and exceeding 300,000 barrels of crude oil per day in net exports.

However, a change in trend soon began with state intervention in the market. Domestic consumption with fixed sales prices for oil producers was less attractive than the export market, encouraging private companies to overproduce in order to export oil and increase revenues exponentially. With the rise in oil prices during the so-called "commodity super-cycle" during the first decade of this century, the price difference between exports and domestic sales increased, generating a real incentive to focus on production. Exploration was thus left in the background, since domestic consumption was growing rapidly due to tax incentives and a near horizon was foreseen without the possibility of exports and, therefore, lower income from the increase in reserves.

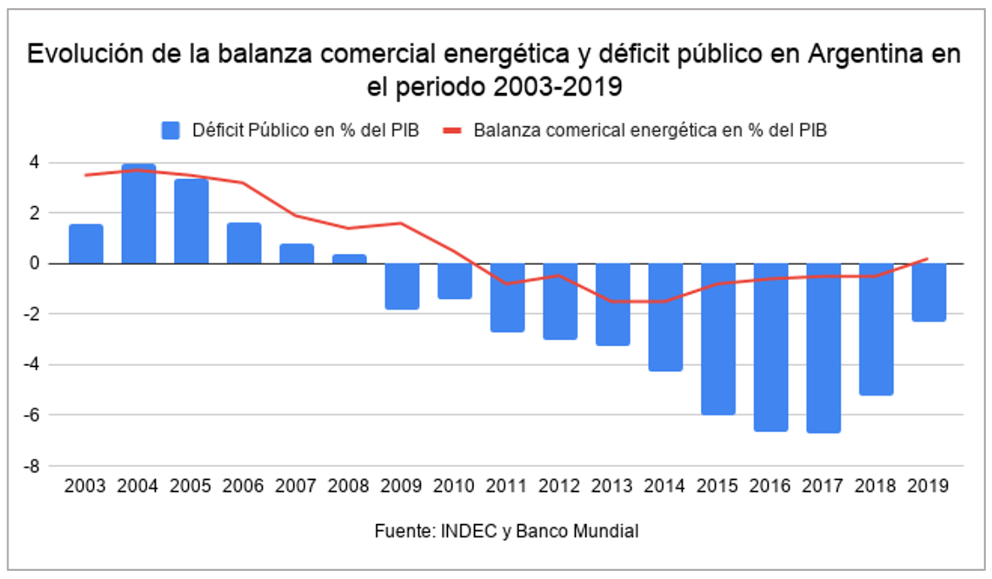

The 2001 crisis was overcome in a context of fiscal and trade surplus, which made it possible to recover the confidence of international creditors and reduce the public debt Issue . The energy sector was precisely the main driver of this recovery, accounting for more than half of the trade surplus in the 2004-2006 period and one of Argentina's main sources of fiscal revenues. However, as mentioned above, this production was not sustainable due to the existence of a fiscal framework that distorted oil companies' incentives in favor of immediate consumption without investing in exploration. By 2004, a new tariff was applied to crude oil exports that floated on the basis of the international price of crude oil, reaching 45% if the price was above US$45. The excessively rentier approach of Néstor Kirchner's presidency ended up dilapidating the incentives for investment by the sector, although it is true that they allowed for a spectacular increase in derived fiscal revenues, boosting Argentina's generous social and debt payment plans. As a good sample this decline in exploration, in the 1980s more than 100 exploratory wells were drilled annually, in 1990 the figure exceeded 90 and by 2010 the figure was 26 wells per year. This figure is especially dramatic if we take into account the dynamics that the oil and gas sector usually follows, with large investments in exploration and infrastructure in times of high prices, as was the case between 2001-2014.

In 2011, after a decade of debates on the oil sector in Argentina, President Cristina Fernández decided to expropriate 51% of the shares of YPF held by Repsol, citing reasons of energy sovereignty and the decline of the sector. This decision followed the line taken by Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales in 2006 to increase the weight of the State in the hydrocarbons sector at a time of electoral success for the Latin American left. The expropriation took place the same year that Argentina became a net energy importer and coincided with the finding of the large shale reserves in Neuquén precisely by YPF, today known as Vaca Muerta. YPF at that time was the direct producer of approximately one third of Argentina's total Issue . The expropriation took place at the same time as the imposition of the "cepo cambiario", a capital control system that made private foreign investment in the sector even less attractive. Not only was the country unable to recover its energy self-sufficiency, but it also entered a period of intense imports that hindered access to dollars and produced a large part of the macroeconomic imbalance of the current economic crisis.

The arrival of Mauricio Macri in 2015 foresaw a new stage for the sector with policies more favorable to private initiative. One of the first measures was to establish a fixed price at the "wellhead" of Vaca Muerta's operations with the idea of encouraging the start-up of projects. As the economic crisis worsened, the unpopular measure of increasing electricity and fuel prices by more than 30% was chosen, generating enormous discontent in the context of a constant devaluation of the Argentine peso and the rising cost of living. The Energy portfolio was marked by enormous instability, with three different ministers who generated enormous legal insecurity by constantly changing the regulatory framework for hydrocarbons. Renewable solar and wind energy, boosted by a new energy plan and a greater liberalization of investments, managed to double their energy contribution during Mauricio Macri's stay in the Casa Rosada.

The first years of Alberto Fernández have been marked by an unconditional support to the hydrocarbons sector, being Vaca Muerta the central axis of his energy policy, announcing the Gas Plan 2020-2023 that will subsidize part of the investment in the sector. On the other hand, despite the context of health emergency during 2020, 39 renewable energy projects were installed, with an installed power of about 1.5 GW, which represents an increase of almost 60% over the previous year. In any case, the continuity of this growth will depend on the access to foreign currency in the country, essential to be able to buy panels and windmills from abroad. The renewable energy boom in Argentina led Danish Vestas to install the first windmill assembly plant in the country in 2018, which already has several plants producing solar panels to supply domestic demand.

Characteristics of Vaca Muerta

Vaca Muerta is not a field from a technical point of view, it is a sedimentary training of enormous magnitude and has scattered deposits of natural gas and oil that can only be exploited with unconventional techniques: hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. These characteristics make Vaca Muerta a complex activity, which requires attracting as much talent as possible, especially from international players with experience in the exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbons. Likewise, conditions in the province of Neuquén are complex considering the scarcity of rainfall and the importance of the fruit and vegetable industry, in direct competition with the water resources required for the exploitation of unconventional oil.

Since its finding, the potential of Vaca Muerta has been compared to that of the Eagle Ford basin in the United States, a producer of more than one million barrels per day. Evidently, the Neuquén region has neither the oil business ecosystem of Texas nor its fiscal facilities, making what could be geologically similar in reality two totally different stories. In December 2020 Vaca Muerte produced 124,000 barrels of oil per day, a figure that is expected to gradually increase throughout this year to reach 150,000 barrels per day, about 30% of the 470,000 barrels per day that Argentina produced in 2020. Natural gas follows a slower process, pending the development of infrastructure that will allow the transportation of large volumes of gas to consumption and export centers. In this regard, Fernández announced in November 2020 the Argentine Gas Production Promotion Plan 2020-2023 with which the Casa Rosada seeks to save dollars via import substitution. The plan facilitates the acquisition of dollars for investors and improves the maximum selling price of natural gas by almost 50%, to US$3.70 per mbtu, in the hope of receiving the necessary investment, estimated at US$6.5 billion, to achieve gas self-sufficiency. Argentina already has the capacity to export natural gas to Chile, Uruguay and Brazil through pipelines. Unfortunately, the floating vessel exporting natural gas from Vaca Muerte left Argentina at the end of 2020 after YPF unilaterally broke the ten-year contract with the vessel's owner, Exmar, citing economic difficulties, limiting the capacity to sell natural gas outside the continent.

One of the great advantages of Vaca Muerta is the presence of international companies with experience in the aforementioned US unconventional oil basins. The learning curve of the North American fracking sector after 2014 is being applied in Vaca Muerta, which has seen drilling costs drop by 50% since 2014 while gaining in productivity. The arrival of US capital may accelerate if Joe Biden's administration fiscally and environmentally restricts oil activities in the country, agreement to his environmentalist diary . Currently the main operator in Vaca Muerta after YPF is Chevron, followed by Tecpetrol, Wintershell, Shell, Total and Pluspetrol, in an ecosystem with 18 oil companies working in different blocks.

Vaca Muerta as a national strategy

It is clear that achieving energy self-sufficiency will help Argentina's macroeconomic problems, the main headache for its citizens in recent years. Not Exempt environmental risk, Vaca Muerta can be a lifeline for a country whose international credibility is at historic lows. The pro-hydrocarbon narrative assumed by Alberto Fernandez follows the line of his Mexican counterpart Andres Lopez Obrador, with whom guide intends to lead a new moderate left-wing axis in Latin America. The ghost of the nationalization of YPF by the now vice-president Cristina Fernandez, as well as the recent breach of contract with Exmar continue to generate uncertainty among international investors. On the other hand, the poor financial status of YPF, the main player in Vaca Muerta, with a debt of more than US$ 8 billion, is a major burden for the country's oil expectations. Likewise, Vaca Muerta is far from realizing its potential, with significant but insufficient production to guarantee revenues that would bring about a radical change in Argentina's economic and social status . In order to guarantee its success, a context of favorable oil prices and the fluid arrival of foreign investors are needed. Two variables that cannot be taken for granted given the Argentine political context and the increasingly strong decarbonization policy of the traditional oil companies.

The big question now is how to reconcile large-scale fossil fuel development with Argentina's latest climate change commitments: to reduce CO2 emissions by 19% by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Similarly, the promising trajectory in renewable energy development during Mauricio Macri's presidency may lose momentum if the oil and gas sector attracts public and private investment, displacing solar and wind.

Vaca Muerta will most probably advance slowly but surely as international oil prices stabilize upwards. The possibility of generating foreign currency and boosting an Economics on the verge of collapse should not be underestimated, but expecting Vaca Muerta to solve Argentina's problems by itself can only end in a new episode of frustration in the southern country.