The upcoming gas self-sufficiency of its two major buying neighbors forces the Bolivian government to look for alternative markets

![Yacimientos Pretrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB) gas plant [Corporación YPFB]. Yacimientos Pretrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB) gas plant [Corporación YPFB].](/documents/10174/16849987/bolivia-gasnatural-blog.jpg)

▲ Yacimientos Pretrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB) gas plant [Corporación YPFB].

ANALYSIS / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa

Bolivia, under Evo Morales, is the only economic success story of all the Latin American countries that embraced left-wing populism at the beginning of this century. Together with Panama and the Dominican Republic, Bolivia has achieved the highest GDP growth in the region in the last five years, and all this in a difficult context of decline on the part of its main trading partners: Argentina and Brazil[1]. The political stability brought by Evo Morales since 2006, coupled with prudent counter-cyclical macroeconomic policies and a new hydrocarbon management are part of the formula for this success. Nevertheless, there are enormous economic and political risks for Bolivia. On the one hand, natural gas accounts for 30% of exports and its destination is exclusively Brazil and Argentina, countries that are close to gas self-sufficiency. Finding alternative routes is not an easy task for a landlocked state, with a diplomatic conflict with Chile and separated by the Andes Mountains from Peru. Moreover, the Bolivian government's bid to exploit lithium through national companies that integrate its processing to favor industrialization is a risky strategy that could leave the country out of the growing world lithium market. Finally, Evo Morales and the MAS have followed a growing authoritarian trend, allowing the reelection of the president, undermining the separation of powers and the recent 2009 constitution. The new Bolivia faces in the next decade the challenge of reorienting its natural gas exports, diversifying its Economics and consolidating a real democracy that will allow a sustained growth of its Economics and its role as a regional actor.

Natural Gas: at the center of the 21st century political discussion

During the failed oil explorations in the Chaco in the 1960's, abundant natural gas reserves of great economic potential were finding . Although it was a less valuable resource than crude oil, an incipient gas industry was soon developed by foreign companies, mainly American, such as Standard Oil. In 1972, the first nationalization took place, with the emergence of YPFB as the state business in charge of the exploration, production, transportation and refining of Bolivian energy resources in partnership with foreign companies. That same year, the first export gas pipeline to Argentina was built. By 1999, Bolivia will export natural gas to Brazil through the Santa Cruz-Sao Paulo pipeline, whose project took more than eight years of negotiations and construction work and introduced Petrobras as a major player in the sector. Thus, Bolivia enters the 21st century with a growing gas industry, mostly privatized by the first government of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, and boosted by a very favorable fiscal model for foreign companies[2].

The year 2001 marked the beginning of a convulsive political stage in Bolivia with the so-called Water War. A wave of protests arose from the privatization of municipal water services in the framework of financial negotiations between the IMF and the government of Hugo Banzer. At the nerve center of these protests in Cochabamba emerged the figure of Evo Morales, a coca growers' leader who will increase his popularity unstoppably. Gas became the protagonist in 2003, with a new wave of protests against the construction of a natural gas pipeline from Tarija to Mejillones (Chile) for consumption by the Chilean mining industry and export to Mexico and the USA in the form of LNG. The civil service examination the project argued the historical incoherence of contributing Bolivian resources to the exploitation of the mining region lost to Chile in the War of the Pacific (1879-1883) and which deprived Bolivia of an outlet to the sea. In addition, an alternative, more costly gas pipeline through Peru was proposed, but which would supposedly benefit the northern region of Bolivia and would not be a national humiliation. The protests took a nationalist and indigenist turn and became a real revolution that blocked La Paz, the international airport and plunged the whole country into violence and shortages. President Lozada resigned and most of his government fled abroad, while the project was cancelled and buried forever.

The new president Mesa came to power with the promise to call for a binding referendum on gas, the establishment of a Constituent Assembly and a reform of the Hydrocarbons Law, including a review of the privatization processes. The referendum ended up giving the victory to Carlos Mesa's proposals, although with a leave participation and a confusing essay of the questions. President Mesa, unable to capitalize on the legitimacy granted by the plebiscite Withdrawal to the position , called early presidential elections in 2005, which brought to power the first indigenous president in the history of Bolivia, Evo Morales, with an absolute majority. Natural gas thus became the main catalyst for political change in Bolivia.

Hydrocarbon reform

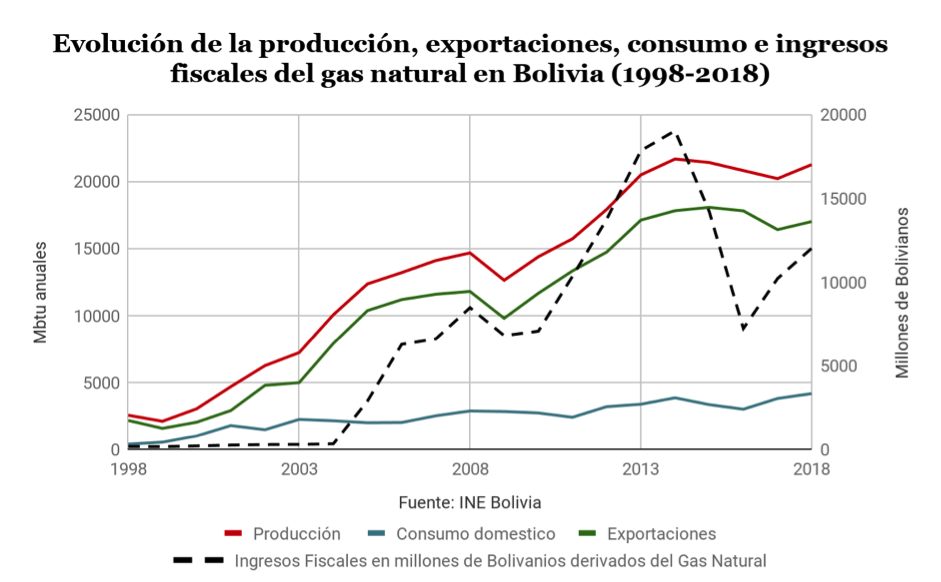

The arrival of Evo Morales brought about a profound change in the hydrocarbons legal framework . In 2006, the new hydrocarbons law "Heroes del Chaco" was enacted, nationalizing Bolivia's energy resources, expropriating 51% of the shares of companies involved in the sector and establishing a direct tax on hydrocarbons of 50% subject to an extra 32% royalty to YPFB in those fields with more than 100 mcf of annual production[3]. This legislation, in the words of Evo Morales "turned the tables, going from 18% to 82% of the State's income on hydrocarbons"[4]. The legislation, although adorned with radical revolutionary rhetoric, has proven to be moderate and viable in the medium term, since it allows in the internship much less burdensome tax formulas for energy multinationals and did not imply large expropriations of assets. As can be seen in the graph below, tax revenues from natural gas have grown enormously since 2005, the year of the reform, without dramatically affecting natural gas production. In addition, this reform was accompanied by record highs in the price of raw materials in 2006, 2007 and 2008, cushioning the percentage reduction in foreign companies' revenues. In 2009 Bolivia included in article 362 the primacy of oil service contracts, a formula in which multinationals do not obtain any rights over the hydrocarbons extracted, but are remunerated for the services rendered.

Since the reform, exports have been relatively stable, buoyed by growing demand in both Brazil and Argentina. The most controversial case occurred in the particularly cold winter of 2016, when Bolivia halted exports due to maintenance work at the Margarita field. This event unmasked a stubborn reality about Bolivia's proven natural gas reserves and the need to increase exploration and drilling work in the country. Bolivia's current reserves amount to 283 bcm (10 tcf), enough for only 10 years of export activity at the current rate. Aware of this limiting status , the YPFB corporation has launched an investment campaign for 2019 amounting to US$ 1.45 billion, of which US$ 450 million will be dedicated to exploration work[5]. Much of the investment in the sector in recent years has been aimed at industrializing natural gas production instead of exploration work, building refining plants such as the Bulo Bulo ammonia and urea plant[6]. Total, Shell, Repsol and Petrobras are currently working in exploration and production[7]. This effort is intended to respond to the IMF report that considered Bolivia's natural gas reserves to be too scarce to turn the country into a regional energy center, Evo Morales' greatest aspiration[8]. For YPFB, there are probable reserves of 850 bcm (35 tfc) that would guarantee a long life for the gas sector, but it should rethink its fiscal policy in order to attract foreign companies, which currently account for only 20% of total investment[9].

The future of Bolivian natural gas

agreement to the contracts signed with Brazil (1999) and Argentina (2005), export prices are indexed to a basket of hydrocarbons, which in general has guaranteed Bolivia a very favorable price, higher than the Henry Hub price, but which makes the country equally dependent on fluctuations in international commodity prices. However, the revolution of non-conventional technology and new forms of transportation, now more economical, such as LNG, are transforming the reality of the natural gas market in the Southern Cone. This new situation, linked to the end of the contracts with Brazil in 2019 and Argentina in 2026, puts in check the future of the main asset of Bolivian Economics .

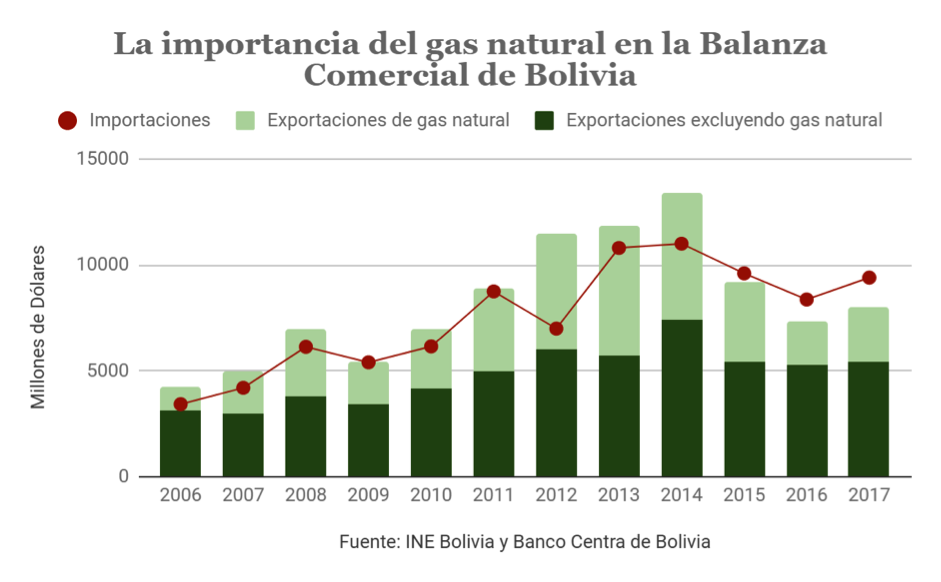

As sample in the graph, the Bolivian trade balance and its fiscal stability depend on the exported volumes of natural gas and its international price. The survival of the current Bolivian economic model and the presidency of Evo Morales depend to a large extent on the income derived from this hydrocarbon, which is a fundamental factor for the future of the Plurinational Republic of Bolivia.

Brazil

Since 1999, Brazil has become the main destination for natural gas exports, being Bolivia's only client in the 2001-2005 period. This position allowed Petrobras to entrance as the main investor in the sector until the year of nationalization, which meant an important diplomatic friction between both countries. It was the complicity between Morales and Lula, as well as the importance of maintaining harmony between the leftist governments in the region, which allowed avoiding a major confrontation between the two countries. Despite the words of Petrobras' president in 2006, Sergio Gabrielli, announcing the end forever of the company in Bolivia, it has continued to be an important investor due to the profitability of its activities and the strategic importance of Bolivian gas for Brazil.

It seems clear that natural gas will play an important role in Brazil's future, since the main source of electricity in the country, hydroelectric power, requires other sources to replace it when there is a shortage of rainfall, as occurred between 2012 and 2014. This context favored the entrance of natural gas in the electricity mix, which went from 5% in 2011 to 25% by 2015[10]. However, Brazil started a decade ago with the revolutionary pre-salt hydrocarbon exploitations, which have allowed the country to increase its crude oil production from 1.8 mbd in 2008 to 2.6 mbd in 2018. Natural gas production associated with these fields is expected to enter the Brazilian market as the necessary infrastructure connecting the off-shore fields to the still insufficient pipeline network is built, something that is expected to improve with the entrance of private players into the sector following the 2016 energy reform. Likewise, Brazil already has 3 plants to import LNG, allowing it to diversify its imports, as it did during 2018 when Bolivia was unable to supply the 26 million cubic meters per day agreed in 1999. All this puts Petrobras and Bolsonaro, located in the ideological antipodes of Morales, in a privileged position for negotiation, and who could bet on increasing imports of the increasingly cheaper North American LNG and reduce the Bolivian gas Issue In any case, due to certain non-compliances in the supply of gas from Bolivia, the contract will be extended for at least two more years until the outstanding volumes to be submit , which Brazil has already paid for, are reached.

Argentina

The other natural gas market for Bolivia is also undergoing profound transformations, in this case derived from unconventional shale and tight oil techniques. The Vaca Muerta field, considered one of the largest shale deposits in the world, has begun to produce the first returns after years of investments by YPF and other multinationals. Despite Argentina's economic instability and the fiscal reforms demanded by the IMF which will delay the total development of this giant field[11], it is expected that by 2022 its production will cover approximately 80% of Bolivian imports, returning to the path of self-sufficiency achieved in much of the 1990s and 2000s[12]. For the time being, Argentina has already managed to renegotiate the volumes of natural gas imported in summer and winter in a way that is more favorable to domestic demand[13]. In addition, Argentina authorized natural gas exports to Chile after 12 years of interruption[14] and made its first LNG export in May 2019[15], which are early signs of growing domestic production.

It seems clear that the Argentine market will not have a long run for Bolivian natural gas and will probably end its imports when the contract expires in 2026. Other options include using the entire Argentine pipeline network as a transit to other destinations via LNG or to neighbors such as Uruguay, Paraguay or even Chile.

Peru

For some months now, Bolivia has been engaged in a public diplomacy campaign to extend a gas export pipeline to Puno, a Peruvian city located on Lake Titikaka. Although Peru has significant natural gas production in Camisea that allows it to export large quantities of LNG, the country launched a program known as Siete Regiones (Seven Regions) to universalize access to natural gas. Southern Peru can be supplied more economically through Bolivian imports due to the proximity of the La Paz pipeline, but there is reluctance, especially in the civil service examination fujimorista, to import a surplus good in the country. This formula would be integrated into a plan to export liquefied petroleum gas from Bolivia to the same area, while Peru would build a gas pipeline to import oil and derivatives from the Pacific port of Ilo to La Paz. For Bolivia, the Peruvian market may be a temporary solution while exports continue to diversify, but it will have an early expiration date given the Peruvian natural gas reserves, double the Bolivian reserves, and the logical trend towards greater domestic production to cover the demand of the entire country. Likewise, it seems sensible to think that the Peruvian coast will in the future be one of the points through which Bolivia could export its natural gas in the form of LNG if the regional market is saturated.

Chile

From an economic point of view, Chile is the most attractive country for Bolivian exports. It lacks natural gas reserves and its mining area, with high energy demand, is located in an area relatively close to Bolivia's network of gas pipelines and deposits. However, the now century-old dispute over Bolivia's original territories annexed by Chile in the War of the Pacific (1879-1883) has been an insurmountable obstacle in the present century. It is worth mentioning that during the 50's and 60's Bolivia exported oil to Chile and the USA through the Sica Sica-Arica pipeline; that is to say, the refusal to export natural gas to Chile has been a flag used by Evo Morales and not a historical tradition in the relationship between these countries.

After the huge mobilizations caused by the Gas War, Evo Morales was able to catalyze popular fervor and use the territorial dispute to increase his popularity. In fact, a good part of his efforts in the previous legislature were focused on achieving the longed-for exit to the sea through the International Court of Justice in The Hague. In 2018 this court ruled favorably for Chile, ruling that this country has no duty to negotiate with Bolivia a territorial settlement. Morales' refusal to export natural gas to Chile looks set to continue for the duration of his presidency.

However, the 1904 Treaty of Peace and Friendship signed by both states grants Bolivia full customs autonomy in the Chilean ports of Arica and Antofagasta and the right to keep goods in transit for 12 months, with free storage for its imports, and 60 days of free storage for its exports. These conditions seem ideal for the construction of an LNG plant in Arica or Antofagasta to export natural gas by sea while supplying the Chilean north, in need of cheap natural gas to displace coal. The difficult political relations between both countries complicate the viability of this project, which should not be discarded when Morales leaves the presidency and there is greater harmony, as happened with Pinochet and Banzer in power.

Domestic consumption

Domestic consumption of natural gas in Bolivia has grown at an annual rate of 4.5% in the 2008-2018 period, driven by subsidized prices for consumption and the implementation of state projects that aim to provide added value to natural gas extraction, such as the Bulo Bulo urea plant or the Mutún steel industry. Bolivia's per capita income and electricity consumption are expected to continue to increase over the next decade. If the natural gas subsidy Issue grows similarly while export revenues decline, Bolivia's delicate fiscal balance could take a similar path to that of Argentina. The process of domestic industrialization through natural gas does not seem far-fetched either, as long as it is based on market rules and not at the expense of public finances. The country has already achieved self-sufficiency in fertilizers and is already a growing exporter, an example of the economic diversification pursued by the Morales government.

The question: Is there a market for everyone?

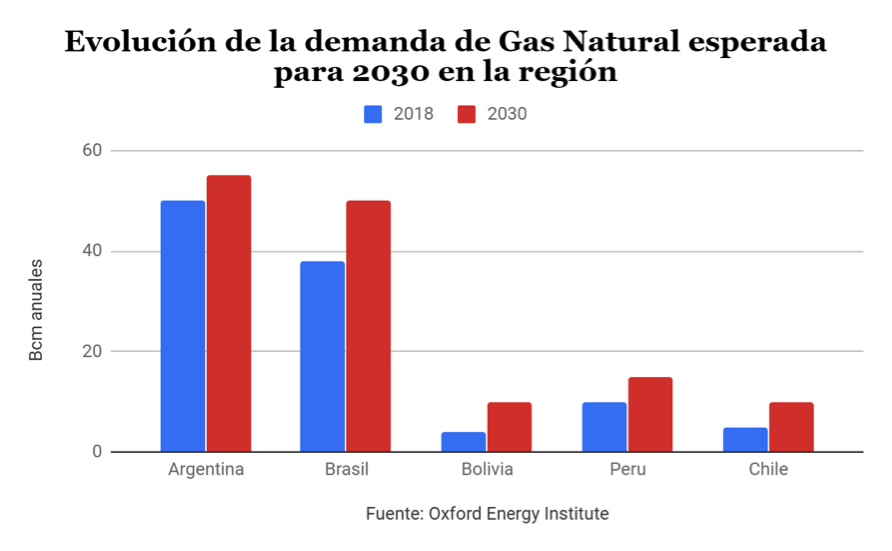

After reviewing the regional context, it may appear that the natural gas market in South America will be saturated by future oversupply. As can be seen in the graph, natural gas demand in the Bolivian neighborhood will increase from 107 bcm to 140 bcm per year by 2030. Peru, Argentina and Brazil are likely to increase their production and may reach self-sufficiency during the 2020s. This complicates the commercialization of Bolivian gas, but does not make it impossible. In the first place, the geographical reality of South America makes certain cross-border projects more economical than other internal ones, as in the case of southern Peru. Likewise, the increasingly lower costs of exporting gas by sea make it possible to find a market for surplus regional production, as in the case of Peru, which concentrates its gas exports to Spain. In a context of increasing energy interconnection, Bolivia will be able to continue exporting natural gas, albeit from a less privileged position and having to invest in export infrastructure. The major challenges are focused on increasing exploration activities by attracting more foreign and private investment, as well as the search for new markets, with the Chilean issue being a central element in this discussion.