Breadcrumb

Blogs

![Members of the Blue Helmets in their deployment in Mali [MINUSMA]. Members of the Blue Helmets in their deployment in Mali [MINUSMA].](/documents/10174/16849987/minusma-blog.jpg)

▲ Members of the Blue Helmets in their deployment in Mali [MINUSMA].

April 20, 2020

ESSAY / Ignacio Yárnoz

INTRODUCTION

It has been 72 years since the first United Nations peacekeeping operation was deployed in Israel/Palestine to supervise the ceasefire agreement between Israel and his Arab neighbours. Since then, more than 70 peacekeeping operations have been deployed by the UN all over the world, though with special attention to the Middle East and Africa. Over these more than 70 years, hundreds of thousands of military personnel from more than 120 countries have participated in UN peacekeeping operations. Nowadays, there are 13 UN peacekeeping operations deployed in the world, seven of which are located in African countries supported by a total of 83,436 thousand troops (around 80 percent of all UN peacekeepers deployed around the world) and thousands of civilians. The largest missions in terms of number of troops and ambitious objectives are those in the Democratic Republic of Congo (20,039 troops), South Sudan (19,360 troops), and Mali (15,162 troops)[1].

Peacekeepers in Africa, as in other regions, are given broad and ambitious mandates by the Security Council which include civilian protection, counterterrorism, and counterinsurgency operations or protection of humanitarian relief aid. However, these objectives must go hand by hand with the core UN peacekeepers principles, which are consent by the belligerent parties, impartiality (not neutrality) and the only use of force in case of self-defence[2].

Although peace operations can be important for maintaining stability and safeguarding democratic transitions, multilateral institutions such as UN face challenges related to country contributions, training, a very hostile environment and relations with host governments. It is often stated that these missions have failed largely because they were deployed in a context of ongoing wars where the belligerents themselves did not want to stop fighting or preying on civilians and yet have to manage to protect many civilians and reduce some of the worst consequences of civil war.

In addition, UN peacekeepers are believed to be deployed in the most recent missions to war zones where not all the main parties have consented. There is also mounting international pressure for peacekeepers to play a more robust role in protecting civilians. Despite the principle of impartiality, UN peacekeepers have been tasked with offensive operations against designated enemy combatants. Contemporary mandates have often blurred the lines separating peacekeeping, stabilization, counterinsurgency, counterterrorism, atrocity prevention, and state-building.

Such features have often been referred to the case of the peacekeeping operation in Mali (MINUSMA) as I will try to sum up in this essay. This mission, ongoing since 2013 is on its seventh year and tensions between the parties have still not ceased due to several reasons I will further explain in this essay. Through a summarized history of the ongoing conflict, an explanation of the current military/police deployment, the engagement of third parties and an assessment on the risks and opportunities of this mission as well as an analysis of its successes and failures I will try to give a complete analysis on what MINUSMA is and its challenges.

Brief history of the conflict in Mali

During the last 8 years, Mali has been immersed in a profound crisis of Governance, partner instability, terrorism and human rights violations. The crisis mentioned stems from several factors I will try to develop in this first part of the analysis. The crisis derives from long-standing structural conditions that Mali has experienced, such as ineffective Governments due to weak State institutions; fragile social cohesion between the different ethnic and religious groups; deep-rooted independent feelings among communities in the north due to marginalization by the central Government and a weak civil society among others. These conditions were far exacerbated by more recent instability, a spread corruption, nepotism and abuse of power by the Government, instability from neighboring countries and a decreased effective capacity of the national army.

It all began in mid-January 2012 when a Tuareg movement called Mouvement National pour la Libération de l'Azawad (MNLA) and some Islamic armed groups such as Ansar Dine, Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Mouvement pour l'Unicité et le Jihad en Afrique de l'Ouest (MUJAO) initiated a series of attacks against Government forces in the north of the country[3]. Their primary goals for these rebel groups though different could be summarized into declaring the Northern regions of Timbuktu, Kidal and Gao (the three together called Azawad) independent from the Central Government of Mali in Bamako and re-establishing the Islamic Law in these regions. The Tuareg led rebellion was reinforced by the presence of well-equipped and experienced combatants returning from Libya's revolution of 2011 in the wake of the fall of Gadhafi's regime[4].

By March 2012, the Malian Institutions had been overwhelmingly defeated by the rebel groups and the MNLA seemed to almost have de facto taken control of the North of Mali. As a consequence of the ineffectiveness to handle the crisis, on 22 March a series of disaffected soldiers from the units defeated by the armed groups in the north resulted in a military coup d'état led by mid-rank Capt Aamadou Sanogo. Having overthrown President Amadou Toumane Toure, the military board took power, suspended the Constitution and dissolved the Government institutions[5]. The coup accelerated the collapse of the State in the north, allowing MNLA to easily overrun Government forces in the regions of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu and proclaim an independent State of Azawad on 6 April. The Military board promised that the Malian army would defeat the rebels, but the ill-equipped and divided army was no match for the firepower of the rebels.

Immediately after the coup, the International Community condemned this act and lifted sanctions against Mali if the situation wasn't restored. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) appointed the President of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaoré, as the mediator on the crisis and compromised the ECOWAS would help Malian Government to restore order in the Northern region if democracy was brought back[6]. On 6 April, the military board and ECOWAS signed a framework agreement that led to the resignation of Capt Aamadou Sanogo and the appointment of the Speaker of the National Assembly, Dioncounda Traoré, as interim President of Mali on 12 April. On 17 April, Cheick Modibo Diarra was appointed interim Prime Minister and three days later, he announced the formation of a Government of national unity.

However, something happened during the rest of the year 2012 after the Malian government forces had been defeated. Those who were allies one day, became enemies of each other and former co-belligerents Ansar Dine, MOJWA, and the MNLA soon found themselves in a conflict.

Clashes began to escalate especially between the MNLA and the Islamists after a failure to reach a power-sharing treaty between the parties. As a consequence, the MNLA forces soon started to be driven out from the cities of Kidal, Timbuktu and Gao. The MNLA forces lacked as many resources as the Islamist militias and had experienced a loss of recruits who preferred the join the better paid Islamist militias. However, the MNLA stated that it continued to maintain forces and control some rural areas in the region. As of October 2012, the MNLA retained control of the city of Ménaka, with hundreds of people taking refuge in the city from the rule of the Islamists, and the city of Tinzawatene near the Algerian border. Whereas the MLNA only sought the Independence of Azawad, the Islamist militias goal was to impose the sharia law in their controlled cities, which drove opposition from the population.

Foreign intervention

Following the events of 2012, the Malian interim authorities requested United Nations assistance to build the capacities of the Malian transitional authorities regarding several key areas to the stabilization of Mali. Those areas were the reestablishment of democratic elections, political negotiations with the opposing northern militias, a security sector reform, increased governance on the entire country and humanitarian assistance.

The call for assistance came in the form of a UN deployment in mid-January 2013 authorized by Security Council resolution 2085 of 20 December 2012. This resolution gave the UN a mandate with two clear objectives: provide support to (i) the on-going political process and (ii) the security process, including support to the planning, deployment and operations of the African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA)[7].

The newly designated mission was planned to be an African led mission (Africa Union and ECOWAS) and funded through the UN trust fund and the European Union Africa Peace Facility. The mission was mandated several objectives: (i) contribute to the rebuilding of the capacity of the Malian Defence and Security Forces; (ii) support the Malian authorities in recovering the areas in the north; (iii) support the Malian authorities in maintaining security and consolidate State authority; (iv) provide protection to civilians and (iv) support the Malian authorities to create a secure environment for the civilian-led delivery of humanitarian assistance and the voluntary return of internally displaced persons and refugees.

However, the security situation in Mali further deteriorated in early January 2013, when the three main Islamist militias Ansar Dine, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa and Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, advanced southwards. After clashing with the Government forces north of the town of Konna, some 680 kilometers from Bamako, the Malian Army was forced to withdraw. This advance by the Islamist militias raised the alarms in the International arena as they were successfully taking control of key areas and strategic spots in the country and could soon advance to the capital if nothing was done.

The capture of Konna by extremist groups made the Malian transitional authorities to consider requesting once again the assistance of foreign countries, in particular to its ancient colonizer France, who accepted launching a military operation to support the Malian Army. It is also true that France was already keen on intervening as soon as possible due the importance of Sévaré military airport, located 60 km south of Konna, for further operations in the Sahel area.

Operation Serval, as coined by France, was initiated on 11 January with a deployment of a total of 3,000 troops[8] and air support from Mirage 2000 and Rafale squadrons. In addition, the deployment of AFISMA to support the French deployment was fostered. As a result, the French and African military operations alongside the Malian army successfully improved the security situation in northern areas of Mali. By the end of January, State control had been restored in most major northern towns, such as Diabaly, Douentza, Gao, Konna and Timbuktu. Most terrorist and associated forces withdrew northwards into the Adrar des Ifoghas mountains and many of their leaders such as Abdelhamid Abou Zeid were reported eliminated.

Despite taking control back to the government authorities and restoring the territorial integrity of the country, serious security challenges remained. Although the main cities had been taken back, terrorist attacks remained frequent, weapons proliferated in the rural and urban areas, drug smuggling was increasing and other criminal activities were also maintained active, which undermine governance and development in Mali. Therefore, the fight just transitioned from a territorial and conventional war to a guerrilla style warfare much more difficult to neutralise.

United Nations deployment

Following the gradual withdrawal of the French troops from Mali (Operation Serval evolved to Operation Barkhane in the Sahel region), AFISMA took responsibility to secure the stabilization and the implementation of a transitional roadmap which demanded more resources and engagement from more countries. As a consequence, AFISMA mission officially transitioned to be MINUSMA (United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali) by Security Council Resolution 2100 of April 25, 2013[9].

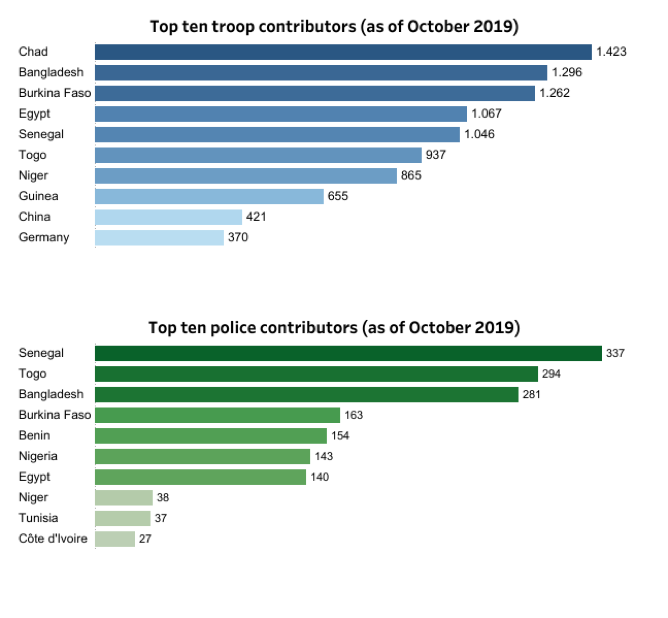

Seven years after, MINUSMA mission accounts with a deployment of 11,953 military personnel, 1,741 police personnel and 1,180 civilians (661 national - 585 international, including 155 United Nations Volunteers)[10] deployed in 4 different sectors: Sector North (Kidal, Tessalit, Aguelhoc) Sector South (Bamako) Sector East (Gao, Menaka, Ansongo) Sector West (Tombouctou, Ber, Diabaly, Douentza, Goundam, Mopti-Sevare). The $1 Billion budget mission (financed by UN regular budget on Peacekeeping operations) accounts with personnel from more than 50 different countries being Chad, Bangladesh or Burkina Faso the biggest contributors in terms of number of troops (Figure 1).

The command and control of the ground forces is headed by both commanders Lieutenant General Dennis Gyllensporre (military deployment) and MINUSMA Police Commissioner Issoufou Yacouba (police deployment). Regarding the political leadership of the mission, the Special Representative of the Secretary-general (SRSG) and Head of MINUSMA is Mr. Mahamat Saleh Annadif, an experienced diplomat on peace processes in Africa and former minister of Foreign Affairs of Chad.

Other international actors engaged

MINUSMA however is not the only international actor engaged in the security and political process of Mali. Institutions as the European Union are also on the ground helping specifically on the training of the Malian Army and helping develop their military capabilities.

The European Union Training Mission in Mali[11] (EUTM Mali) is composed of almost 600 soldiers from 25 European countries including 21 EU members and 4 non-member states (Albania, Georgia, Montenegro and Serbia). Since the beginning of the mission initially designed to end 15 months after the start in 2013 (First Mandate), there have been several extensions of the periods to end the mission by Council Decision (Second Mandate 2014-2016, Third Mandate 2016-2018) until today where we are on the Fourth Mandate (Extended until 2020 by Council Decision 2018/716/CFSP in May 2018). The strategic objectives of the 4th Mandate are:

-

1st to contribute to the improvement of the capabilities of the Malian Armed Forces under the control of the political authorities.

-

2nd to support G5 Sahel Joint Force, through the consolidation and improvement of the operational capabilities of its Joint Force, strengthening regional cooperation to address common security threats, especially terrorism and illegal trafficking, especially of human beings.

Regarding this last actor mentioned, the G5 Sahel Joint force (Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad) is an intergovernmental cooperation framework created on 16 February 2014 and seeks to fight insecurity and support development in the Sahel Region with the train and support of the European Union and external donors.

Its first operation, launched on July 2017, consisted in a Cross-Border Joint Force settled in Bamako to fight terrorism, cross-border organized crime and human trafficking in the G5 Sahel zone in the Sahel region. The United Nations Security Council welcomed the creation of this Joint Force in Resolution 2359 of 21 June 2017, which was sponsored by France[12]. At full operational capability, the Joint Force will have 5,000 soldiers (seven battalions spread across three zones: West, Centre and East). It is active in a 50 km strip on either side of the countries' shared borders. Later on, a counter-terrorism brigade is to be deployed to northern Mali.

Finally, as I explained before, France gradually withdrew from Mali and transformed Operation Serval to Operation Barkhane[13], a force, with approximately 4,500 soldiers, spread out between Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad to counter the terrorist threat on these territories. With a budget of nearly €600m per year, it is France's largest overseas operation and engages activities such as combat patrols, intelligence gathering and filling the Governance gap of the absent Government institutions.

Troop and Police contributors to MINUSMA [Source: UN].

Retrieved from MINUSMA Fact Sheet[25].

Assessment on the situation of MINUSMA

Since its establishment, MINUSMA has achieved some of its objectives in its early stages. From 2013 to 2016, the situation in Northern Mali improved, the numbers of civilians killed in the conflict decreased and large numbers of displaced persons could return home. In addition, MINUSMA supported the celebration of new elections in 2013 and assisted the peace process mainly between the Tuareg rebels and the Government. The peace process culminated in the 15 May 2015 with the Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali, commonly referred to as the Algiers Agreement[14][15].

The Algiers Agreement was an accord concluded between the Malian Government and two coalitions of armed groups that were fighting the government and against each other, being (i) the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA) and (ii) the Platform of armed groups (the Platform). Although imperfect, the peace agreement gave the basis to a continued dialogue and steps were made by the Government regarding the devolution of competences to regional institutions, laws of reconciliation and reintegration of combatants and resources devoted to infrastructure projects in the northern regions[16].

However, since 2016 the situation has deteriorated in several aspects. Violence has increased as jihadist groups have been attacking MINUSMA forces, the Forces Armées Maliennes (FAMA), and the Algiers Agreement signatories (CMA and the platform). As a consequence, MINUSMA has sustained an extraordinary number of fatalities compared to other recent UN peace operations.

Since the beginning of the Mission in 2013, 206 MINUSMA peacekeepers have died during service in Mali[17]. In the last report of Secretary General, it is noted that during the months of October, November and December 2019, there have been 68 attacks against MINUSMA troops in the regions of Mopti (46), Kidal (9), Ménaka (5), Timbuktu (4) and Gao (4) resulting in the deaths of two peacekeepers and eight contractors and in injury to five peacekeepers, one civilian and two contractors[18].

During this same period, the Malian Armed Forces have also experienced a loss of 193 soldiers and 126 injured. The deadliest attacks occurred in Boulikessi and Mondoro (Mopti Region) on 30 September; in Indelimane (Ménaka Region) on 1 November; and in Tabankort (Ménaka Region) on 18 November. MINUSMA provided support for medical evacuations for the national defence and security forces, as well as fuel and equipment to reinforce some camps.

In addition, during this last 3 months, there have been 269 incidents, in which 200 civilians were killed, 96 civilians were injured and 90 civilians were abducted. More than 85 per cent of deadly attacks against civilians took place in Mopti Region. Between 14 and 16 November, a series of attacks against Fulani villages in Ouankoro commune resulted in the killing of at least 37 persons.

As we can see from the data, Mopti region has further deteriorated regarding civilian protection and increased terrorist activity. What is more surprising is that this region in not located in the north but rather in the centre of the country. Mopti and Ségou regions in central Mali are where violence is increasingly spreading. Two closely intertwined drivers of violence can be distinguished: interethnic violence and jihadist violence against the state and its supporters.

The attacks directed primarily towards the Malian security forces and MINUSMA by jihadists have been committed by the jihadist group Katiba Macina, which is part of the GSIM (Le Groupe de Soutien à l'Islam et aux Musulmans), a merger organisation resulting from the fusion of Ansar Dine, forces from Al-Qaïda au Maghreb Islamique (AQMI), Katiba Macina and Katiba Al-Mourabitoune. This organisation formed in 2017 has triggered the retreat of an already relatively absent state in the central areas. The Katiba exerts violence against representatives of the state (administrators, teachers, village chiefs, etc.) in the Mopti region, provoking that only 30 to 40 per cent of the territorial administration personnel remains present. Additionally, only 1,300 security forces are stationed across the vast region (spanning 79,000 km²).

Between the Jihadist activities and the retaliation activities by government forces, there has been a collateral consequence as self-defence militias have proliferated. However, these militias have not only exerted self-defence but also criminal activities and competition over scarce local resources. To this problem we have to add the ethnic component where violence exerted by militias is associated with ethnic differences (mainly the Dogon and Fulani). Jihadists have instrumentalised this rivalry to gain sympathizers and recruits and turned the radicalisation problem and the interethnic rivalry into a vicious trap. The ethnicisation of the conflict reinforces the stigmatisation of the Fulani as "terrorists". Meanwhile, the state has tolerated and even cooperated with the Dogon militia to cope with the terrorist threat. However, these groups are supposedly responsible for human rights violations, which again fosters radicalisation among the Fulani population feeling they are left alone in this conflict. As a matter of fact, the Dogon Militia is alleged to be responsible of the 23 March assassination of 160 Fulani in the village of Ogossagou (Mopti Region)[19].

Northern Mali has not remained calm meanwhile, the Ménaka region has also experienced a violence raise. Recent counterterrorism efforts led by ethnically based militias resulted in a counterproductive effects leading to human rights violations and atrocities between Tuareg Daoussahaq and Fulani communities. Due to again the absence Malian security forces or MINUSMA blue helmets, civilians have had no choice but to rely on their own self-protection or on armed groups present in the area, escalating the vicious problem of violence as in the Mopti region.

Strategic dilemmas of MINUSMA

Given this situation, several dilemmas arise in the current situation in which the mission is. The original Mandate of MINUSMA for 5 years has already expired and now the mission is in a phase of renewal year by year, which makes it a suitable time to rethink the overall path where this mission should continue.

The fist dilemma arises given the split of the violent spots between the north and the centre of the country. MINUSMA was originally set up to stabilize the conflict in the north, but MINUSMA's 2019 Resolution 2480[20] has derived some attention and resources to the central regions and particularly on Protection of Civilians while maintaining its presence in the north too. However, the only problem is that this division on two has not come hand in hand with an increase in resources devoted to the mission, which means that attention paid to the central regions may be in spite of gains made in the north, making the MINUSMA mandate even more unrealistic.

This dilemma raises the problem of financing of the mission. As the years passes, financers of the mission (those that contribute to the General Budget on Peace Keeping Operations of UN) such as the US are getting impatient of not seeing results to a mission where $1 Billion is devoted out of the around $8 Billion of the General Budget. The problem is that for MINUSMA to accomplish its mission in Northern Mali, it has to make an enormous military and logistical effort. The ongoing violent situation calls for security precautions that tie up scarce resources which are no longer available for carrying out the mandate. To illustrate the problem, we can look at the expenditures of the mission and discover that around 80 per cent of its military resources are devoted to securing its own infrastructure and the convoys on which the mission depends to supply its instructions[21].

A final dilemma is related to the development of the terrorist threat. As we have analysed in this article, today's conflict in Mali is about terrorism and therefore requires counterterrorist strategies. However, there are people that state that MINUSMA should focus on the political part of the conflict stressing its efforts on the peace agreement. Current counterterrorism efforts conducted by the Malian Army are highly problematic as they have fuelled local opposition due to its poor human rights commitment. It has been reported the use of ethnic proxy militias (Such as the Dogon militias in Mopti region) who are responsible for committing atrocities against the civilian population. This makes the Central Government to be an awkward and not very trustworthy partner for MINUSMA. At the same time, returning to political tasks alone may further destabilize the country and possibly the whole Sahel-West African region.

Conclusion

There is no doubt MINUSMA operates hostile environment where around half of all blue helmets killed worldwide through malign acts since 2013 have lost their lives. However, MINUSMA has been heavily criticized by public opinion in Mali and accused of passivity regarding protection of civilians whereas critics say, blue helmets have placed their own security above the rest. The has contributed to this public perception by using the mission's problems as a scapegoat for its own failures. However, the mission (with its successes and failures) brings more advantages than inconveniences to the overall process of stabilization of Mali[22].

As many diplomats in Bamako and other public officials stress, the mission and its chief, Mahamat Saleh Annadif, play an important role as mediators both in Bamako politics and with respect to the peace agreement. We cannot discredit the mission of its contribution to Mali's stabilisation. As a matter of fact, it is legitimate to claim that the situation would be much worse without MINUSMA. Yet, the mission has not stopped the spread of violence but rather slowed down the deterioration process of the situation.

While much presence is still needed in northern Mali, we should not forget that the core of the problem to Mali's instability is partly on the political arena and therefore needs mediation. Therefore, importance of continuing political and military support to the peace process should not be underestimated.

At the same time, we have seen the situation over protection of civilians has worsened in the central regions, which requires additional resources. Enhancing MINUSMA's outreach and representation might prevent the central regions from collapsing, though solutions need to be found to ensure stability in the long term through mediation as well. Further expanding the mission in the central regions without affecting the deployment in the north and, therefore, not risking the stability of those regions, would require that MINUSMA have additional resources. This would clearly be the best option for Mali.

Resources could for instance be devoted to improve the lack of mobility in the form of helicopters and armoured carriers to make it possible for the mission to expand its scope beyond the vicinity of its instructions. Staying in the instructions makes MINUSMA more of a target than a security provider and only provides security to its nearby zones where the base is physically present. In addition, the most dangerous missions are carried out by African peacekeepers despite lacking adequate means whereas European countries' peacekeepers are mostly based in MINUSMA's headquarters in Bamako, Gao, or Timbuktu. While European peacekeepers possess more sophisticated equipment such as surveillance drones and air support, African troops do not benefit from those and have to face the most challenging geographical and security environments escorting logistical convoys[23].

Additionally, by accelerating the re-integration of former rebels to the Malian security forces, encouraging Malian police training, and demonstrating increased presence through joint patrols in most unstable areas to protect civilians are key to minimize the threat of further violence. Increased state visibility as we have analysed in this essay has driven to insecurity situations. Consequently, if it can be as much of the problem, it can also be the solution to re-establish some of its legitimacy alongside with the signatories of the Peace Accord to show good faith and engagement in the peace process[24].

In the end, any contribution MINUSMA can make will depend on the willingness of Malians to strive for an effective and inclusive government on the one hand and the commitment of the International community on the other. Supporting such a long-term process cannot be done on the cheap. Therefore, countries cannot continue to request to do more with the same or even less resources.

NOTES

[1] United Nations Peacekeeping (n.d.). Where we operate. [online] Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

[2] Renwick, D. (2015). Peace Operations in Africa. [online] Council on Foreign Relations. Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

[3] Welsh, M. Y. (2013, January 17). Making sense of Mali's armed groups. Al Jazeera. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

[4] Timeline on Mali (n.d.). New York Times. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

[5] Oberlé, T. (2012, March 22). Mali : le président renversé par un coup d'État militaire. Le Figaró. Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

[6] MINUSMA (n.d.). History. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

[7] Unscr.com (2012). Security Council Resolution 2085 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 23 Dec. 2019].

[8] BBC News. (2013). France confirms Mali intervention. [online] Available at [Accessed 24 Dec. 2019].

[9] Security Council Resolution 2100 - UNSCR (2013). Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

[10] MINUSMA (n.d.). Personnel. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

[11] EUTM Mali (n.d.). DÉPLOIEMENT - EUTM Mali. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

[12] France Diplomatie: Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (n.d.). G5 Sahel Joint Force and the Sahel Alliance. [online] Available at [Accessed 27 Dec. 2019].

[13] Ecfr.eu. (2019). Operation Barkhane - Mapping armed groups in Mali and the Sahel. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

[14] Un.org (2015). AGREEMENT FOR PEACE AND RECONCILIATION IN MALI RESULTING FROM THE ALGIERS PROCESS. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

[15] Jezequel, J. (2015). Mali's peace deal represents a welcome development, but will it work this time? Jean-Hervé Jezequel. Available at [Accessed 8 Jan. 2020].

[16] Nyirabikali, D. (2015). Mali Peace Accord: Actors, issues and their representation | SIPRI. Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

[17] MINUSMA. MINUSMA Fact Sheet. Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

[18] Digitallibrary.un.org (n.d.)."UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali" OR MINUSMA - United Nations Digital Library System. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

[19] McKenzie, D. (2019). Ogossagou massacre is latest sign that violence in Mali is out of control. Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2019].

[20] Unscr.com. (2019). Security Council Resolution 2480 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 10 Jan. 2019].

[21] United Nations Digital Library System (2019). Budget for the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali for the period from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020. [online] Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2020].

[22] Van der Lijn, J. (2019). The UN Peace Operation in Mali: A Troubled Yet Needed Mission - Mali. [online] ReliefWeb. Available at [Accessed 30 Dec. 2019].

[23] Lyammouri, R. (2018). After Five Years, Challenges Facing MINUSMA Persist. Available at [Accessed 6 Jan. 2020].

[24] Tull, D. (2019). UN Peacekeeping in Mali. [online] Swp-berlin.org. Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

[25] MINUSMA. MINUSMA Fact Sheet. Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

BIBLIOGRAPHY .

United Nations Peacekeeping (n.d.). Where we operate. [online] Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

Renwick, D. (2015). Peace Operations in Africa. [online] Council on Foreign Relations. Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

Timeline on Mali (n.d.). New York Times. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

Welsh, M. Y. (2013, January 17). Making sense of Mali's armed groups. Al Jazeera. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

MINUSMA (n.d.). History. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

Oberlé, T. (2012, March 22). Mali : le président renversé par un coup d'État militaire. Le Figaró. Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

Unscr.com (2012). Security Council Resolution 2085 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 23 Dec. 2019].

BBC News. (2013). France confirms Mali intervention. [online] Available at [Accessed 24 Dec. 2019].

MINUSMA (n.d.). Personnel. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

EUTM Mali (n.d.). DÉPLOIEMENT - EUTM Mali. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

France Diplomatie: Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (n.d.). G5 Sahel Joint Force and the Sahel Alliance. [online] Available at [Accessed 27 Dec. 2019].

Ecfr.eu (2019). Operation Barkhane - Mapping armed groups in Mali and the Sahel. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

Un.org (2015). AGREEMENT FOR PEACE AND RECONCILIATION IN MALI RESULTING FROM THE ALGIERS PROCESS. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

Digitallibrary.un.org (n.d.)."UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali" OR MINUSMA - United Nations Digital Library System. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

United Nations Digital Library System (2019). Budget for the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali for the period from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020. [online] Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2020].

Van der Lijn, J. (2019). The UN Peace Operation in Mali: A Troubled Yet Needed Mission - Mali. [online] ReliefWeb. Available at [Accessed 30 Dec. 2019].

Tull, D. (2019). UN Peacekeeping in Mali. [online] Swp-berlin.org. Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

McKenzie, D. (2019). Ogossagou massacre is latest sign that violence in Mali is out of control. Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2019].

Unscr.com (2019). Security Council Resolution 2480 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 10 Jan. 2019].

Security Council Resolution 2100 - UNSCR (2013). Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

Nyirabikali, D. (2015). Mali Peace Accord: Actors, issues and their representation | SIPRI. Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

Lyammouri, R. (2018). After Five Years, Challenges Facing MINUSMA Persist. Available at [Accessed 6 Jan. 2020].

Jezequel, J. (2015). Mali's peace deal represents a welcome development, but will it work this time? | Jean-Hervé Jezequel. Available at [Accessed 8 Jan. 2020].

[Scott Martelle, William Walker's Wars. How One Man's Private Army Tried to Conquer Mexico, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Chicago Review Press. Chicago, 2019. 312 p.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

The history of U.S. interference in Latin America is long. In plenary session of the Executive Council Manifest destiny of expansion towards the West in the mid-nineteenth century, to extend the country from coast to coast, there were also attempts to extend sovereignty to the South. Those who occupied the White House were satisfied with half of Mexico, which completed a comfortable access to the Pacific, but there were personal initiatives to attempt to purchase and even conquer Central American territories.

The history of U.S. interference in Latin America is long. In plenary session of the Executive Council Manifest destiny of expansion towards the West in the mid-nineteenth century, to extend the country from coast to coast, there were also attempts to extend sovereignty to the South. Those who occupied the White House were satisfied with half of Mexico, which completed a comfortable access to the Pacific, but there were personal initiatives to attempt to purchase and even conquer Central American territories.

One of those initiatives was led by William Walker, who at the head of several hundred filibusters -the American Falange-, snatched the presidency of Nicaragua and dreamed of a slave empire that would attract the investments of American Southerners if slavery was abolished in the United States. Walker, from Tennessee, first tried to create a republic in Sonora, to integrate that Mexican territory into the United States, and then focused his interest on Nicaragua, which was then an attractive passage for Americans who wanted to cross the Central American isthmus to the gold mines of California, where he himself had sought his fortune. Disallowed and detained several times by the US authorities, due to the problems he caused them with the neighboring governments, he was finally expelled from Nicaragua by force of arms and shot to death when he tried to return, setting foot in Honduras.

Scott Martelle's book is both a portrait of the character - someone without special leadership skills and with a rather delicate appearance unbecoming of a mercenary chief, who nevertheless knew how to generate lucrative expectations among those who followed him (2,518 Americans came to enlist) - and a chronicle of his military campaigns in the South of the United States. It also describes well the mid-19th century atmosphere in cities like San Francisco and New Orleans, full of migrants coming from other parts of the country and in transit to wherever fortune would take them.

It also offers a detailed account of the business developed by the magnate Vanderbilt to establish a route, inaugurated in 1851, that used the San Juan River to reach Lake Nicaragua and from there to go out to the Pacific, with the intention of establishing a railroad connection and the subsequent purpose of building a canal in a few years. Although the overland route was longer than the one that at that time was also being traced under similar conditions on the Isthmus of Panama, the boat trip from the United States to Nicaragua was shorter than the one that had to be made to Panama. The latter explains why, during the second half of the 19th century, the Nicaragua canal project had more supporters in Washington than the Panama project.

Although Panama is one of the symbols of US interference in its "backyard", the success of the transoceanic canal project and its return to the Panamanians largely deactivates a "black legend" that still exists in the Nicaraguan case. Nicaragua is probably the Central American country that has experienced the most US "imperialism". The Walker episode (1855-1857) marks a beginning; then followed the US government's own military interventions (1912-1933), Washington's close support for the Somoza dictatorship (1937-1979) and direct involvement in the fight against the Sandinista Revolution (1981-1990).

Walker arrived in Nicaragua attracted by the U.S. interest in the inter-oceanic passage and with the excuse of helping one of the sides fighting in one of the many civil wars between conservatives and liberals that were taking place in the former Spanish colonies. Elevated to chief of the Army, in 1856 he was elected president of a country in which he could barely control the area whose center was the city of Granada, on the northern shore of Lake Nicaragua.

As he established his power, he moved away from any initial idea of integrating Nicaragua into the United States and dreamed of forging a Central American empire that would even include Mexico and Cuba. Slavery, which in Nicaragua had been abolished in 1838 and he reinstated in 1856, entered into his strategy. He imagined it as a means of preventing Washington from renouncing to extend its sovereignty to those territories, given the internal balances in the US between slave and non-slave states, and as a capital attraction for southern slaveholders. He was finally expelled from the country in 1857 thanks to the push of an army assembled by neighboring countries. In 1860 he attempted a return, but was captured and shot in Trujillo (Honduras). His adventure was fueled by the belief in the superiority of the white and Anglo-Saxon man, which led him to despise the aspirations of the Hispanic peoples and to overestimate the warlike capacity of his mercenaries.

Martelle's book responds more to a historicist purpose than an informative one, so its reading is not so much for the general public as for those specifically interested in William Walker's fulibusterism: an episode, in any case, of convenient knowledge about the Central American past and the relationship of the United States with the rest of the Western Hemisphere.

![UNHCR staff building a tent for Venezuelan refugees in the Colombian city of Cúcuta [UNHCR]. UNHCR staff building a tent for Venezuelan refugees in the Colombian city of Cúcuta [UNHCR].](/documents/10174/16849987/acnur-blog.jpg)

UNHCR staff building a tent for Venezuelan refugees in the Colombian city of Cúcuta [UNHCR].

April 3, 2020

COMMENTARY / Paula Ulibarrena

The restrictive measures imposed by the states to try to contain the coronavirus epidemic mean that millions of people are no longer going to work or working from home. But not everyone can stop working or switch to teleworking. There are self-employed people, small businesses, neighborhood stores, street traders or street vendors, and freelance artists who live practically from day to day. For them and for many others who have no income or see their income reduced, expenses will continue to be the same: payment of utilities, rents, mortgages, school fees and, of course, food and medicine.

All these social impacts caused by the coronavirus crisis are already beginning to be questioned among those living in the "red zone" of the epidemic. In Italy, for example, some political groups have demanded that aid should not be given to large companies, but to this group of precarious workers or needy families, and are demanding a "basic quarantine income".

Similar approaches are emerging in other parts of the world and have even led some leaders to anticipate the demands of the population. In France, Emmanuel Macron announced that the government will assume the credits, and suspended the payment of rents, taxes and electricity, gas and water bills. In the United States, Donald Trump's government announced that checks will be sent to each family to face the expenses or risks implied by the pandemic.

In other major crises, the State has come to the rescue of large companies and banks. Now it is demanded that public resources be used to rescue those most in need.

In every crisis, it is the most disadvantaged who have the worst time, today there are more than 126 million people in the world in need of humanitarian attendance , including 70 million forcibly displaced persons. Among these groups, we are beginning to see the first cases of infection (Ninive-Iraq displaced persons camp, Somalia, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Sudan, Venezuela ....), the report of cases in Burkina Faso is particularly illustrative of the challenge of responding in a context where medical care is limited. Malian refugees who were once displaced to Burkina Faso are being forced to return to Mali, and ongoing violence inhibits humanitarian and medical access to affected populations.

Many refugee camps suffer from insufficient hygiene and sanitation facilities, creating conditions conducive to the spread of disease. Official response plans in the United States, South Korea, China and Europe require social distancing, which is physically impossible in many displacement camps and in the crowded urban settings in which many forcibly displaced people live. Jan Egeland, director general of the Norwegian Refugee committee , warned that COVID-19 could "decimate refugee communities."

Jacob Kurtzer of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington warns that national policies of isolation in reaction to the spread of COVID-19 also have negative consequences for people facing humanitarian emergencies. Thus the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration have announced the end of refugee resettlement programs, as some host governments have halted refugee entrance and imposed travel restrictions as part of their official response.

Compounding these challenges is the reality that humanitarian funding, which can barely meet global demand and may be affected as donor states feel they must focus such funds on the Covid-19 response at this time.

On the flip side, the coronavirus could present an opportunity to de-escalate some armed conflicts. For example, the European Union has order a cessation of hostilities and cessation of military transfers in Libya to allow authorities to focus on responding to the health emergency. The Islamic State has issued repeated messages in its Al-Naba bulletin asking fighters not to travel to Europe and to reduce attacks while concentrating on staying free of the virus.

Kurtzer suggests that this is an opportunity to reflect on the nature of humanitarian work abroad and ensure that it is not overlooked. Interestingly, developed countries face real medical vulnerability, indeed Médecins Sans Frontières has opened facilities in four locations in Italy. Cooperating with reliable humanitarian organizations at the national level will be of vital importance to respond to the needs of the population and at the same time develop a greater understanding of the vital work they perform in humanitarian settings abroad.

[Maria Zuppello, Il Jihad ai Tropici. Il patto tra terrorismo islamico e crimine organizzato in America Latina. Paese Edizioni. Roma, 2019. 215 p.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

We usually link jihad with the Middle East. If anything, also with the African Sachel, opening the map to the west, or with the border of Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, opening it to the east. However, Latin America also has a place in this geography. It has it as a place for financing the terrorist struggle - cocaine is a business that the Islamists take advantage of, as happens with heroin in the specific case of the Taliban - and also as a space in which to go unnoticed, off the radar (the Caribbean or Brazilian beaches are the last place that would be imagined as a hiding place for jihadists).

We usually link jihad with the Middle East. If anything, also with the African Sachel, opening the map to the west, or with the border of Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, opening it to the east. However, Latin America also has a place in this geography. It has it as a place for financing the terrorist struggle - cocaine is a business that the Islamists take advantage of, as happens with heroin in the specific case of the Taliban - and also as a space in which to go unnoticed, off the radar (the Caribbean or Brazilian beaches are the last place that would be imagined as a hiding place for jihadists).

Jihad in the Tropics, by Italian researcher Maria Zuppello, deals precisely with that lesser-known aspect of global jihadism: the caipirinha jihadists, to put it graphically, to emphasize the normality with which these radicalized elements live in the Latin American context, although they are criminal networks more sinister than the name might suggest.

Zuppello's research , which is subtitled "the pact between Islamic terrorism and organized crime in Latin America", deals with various countries, although it is in Brazil where the author locates the main connections with the rest of the region and with the international Structures of various jihadist groups. In particular, she points out the link between the religious leader Imran Hosein, who propagates Salafist doctrines, and the attack against the Bataclan conference room in Paris, since his preaching had a special responsibility in the radicalization of one of the terrorists, Samy Amimour. Zuppello also analyzes the cross-contacts of the Brazilians who were arrested in 2016 in the Hashtag operation, in the final stretch of the preparation for the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro.

Zuppello's book begins with a presentation position Emanuele Ottolenghi, a researcher working at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington think tank. Ottolenghi is an expert on Hezbollah's presence in Latin America, on which he has written numerous articles.

In that presentation, Ottolenghi highlights the partnership established between jihadist elements and certain levels of the Latin American left, especially the Bolivarian left. "The extremist messages differ little from the anti-imperialist revolution rhetoric of the radical left, deeply rooted for decades in Latin America," he says. This explains "the appeal of the Islamic revolution to descendants of the Incas in the remote Andean community of Abancay, a four-hour drive from Machu Picchu, and to Cuban and Salvadoran revolutionaries (now dedicated to spreading Khomeini's word in Central America)."

For Ottolenghi, "the central topic of the red-green alliance between Bolivarians and Islamists is the so-called resistance to U.S. imperialism. Behind this revolutionary rhetoric, however, there is more. The creation of a strategic alliance between Tehran and Caracas has opened the door to Latin America for the Iranian Revolutionary Guards and Hezbollah. Venezuela has become a hub for Iran's agents in the region".

Illicit trafficking generates millions of dollars of black money that is laundered through international circuits. The "Lebanese diaspora communities" in areas such as La Guaira (between Venezuela and Colombia), Margarita Island (Venezuela), the free trade zone of Colon (Panama) and the Triple Border (between Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina) are important in this process.

Precisely that Triple Border has been the usual place to refer to when talking about Hezbollah in Latin America. The attacks occurred in Buenos Aires in 1992 and 1994 against the Israeli Embassy and the AMIA, respectively, had their operative origin there and since then, the financial links of that geographic corner with the Shiite extremist group have been frequently documented. Since the arrival of Hugo Chávez to power, there was a convergence between Venezuela and Iran that protected the obtaining of Venezuelan passports by Islamist radicals, who also took over part of the drug trafficking business as Chávez himself involved the Venezuelan state in the cocaine business.

The convergence of interests between organized crime networks in the region and jihadist elements raises the question, according to Zuppello, of whether "Latin America will end up being the new cash machine for financing global jihad", or even "something else: a hideout for fleeing foreign fighters or a new platform for attacks, or both".

One of the specific aspects to which Zuppello refers is the halal sector and its certifications, which is growing exponentially, causing concern among counter-terrorism authorities in various countries, who accuse the sector of concealing terrorist financing and money laundering. The halal meat trade has provided cover for dozens of Iranian meat inspectors, who have permanently settled in the region.

Investigations such as the one carried out in Jihad in the Tropics have led to the recognition of Hezbollah as a terrorist group by several Latin American countries for the first time in 2019.

Alliance maintains its focus on Russia, but for the first time expresses concern over Beijing's actions

NATO had begun 2020 in the spirit of leaving behind the internal problems of its particular annus horribilis - a 2019 in which the organization had reached "brain death," according to French President Emmanuel Macron - but the absence of global normality due to the coronavirus crisis is making it difficult to fully put into internship what was agreed at the London Summit, held last December to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the creation of the Alliance. Precisely, the London Declaration expressed concern about China's actions on issues such as 5G.

![Member countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO]. Member countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO].](/documents/10174/16849987/otan-cumbre-blog.jpg)

North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO] member countries.

March 31, 2020

article / Jairo Císcar

NATO Summits bring together the Heads of State and/or Government of the member countries and serve to take strategic decisions at the highest level, such as the internship of new policies (as, for example, the New Strategic Concept at the Lisbon Summit 2010), the introduction of new members into the Alliance (Istanbul Summit 2004, with seven new members), or the advertisement major initiatives, as was done at the Newport Summit 2014, where the core coalition of what would later become the International Coalition against the Islamic State was announced.

The London Summit took place on December 3 and 4 to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the creation of the Alliance, which had its first headquarters in the British capital. At the work meetings, attended by all 29 member states, the focus was on three main issues: (a) the continuing tension-distension between Washington and Paris; (b) the economic issue, both the trade war between the European and US defense industry and the defense investment of member countries; and (c) the management of an increasingly fractious Turkey.

a) With regard to the Washington-Paris dispute, we witnessed a new chapter in the two ways of understanding the Atlantic Alliance on the part of two of the countries most committed to it. While the US continues to insist on the importance of focusing the Alliance's efforts on an Eastern axis (against Russia and Middle Eastern jihadism), France wants NATO's strategic axis to be centered in the South, in the African Sahel. This is a vision shared and supported by Spain, which participates in several missions on African soil such as EUTM-Mali or the Ivory Detachment in Senegal (which provides strategic transport in the area to the countries participating in AFISMA and especially to France). For Southern Europe, the greatest threat is the jihadist one, and it has its center of gravity in Africa. This is what Macron made known.

b) The economic issue continues to be fundamental, and this was addressed at the Summit. Since the 2014 Newport Summit, in which the 29 members agreed to direct their efforts to increase defense expense to at least 2% of GDP, only nine have achieved the goal (Spain is at the bottom, surpassing only Luxembourg with a derisory 0.92%). The United States, at the head of defense investment within NATO, contributes 22% of the entire budget. The Trump Administration not only wants this increase so that the Alliance has larger, more prepared and modernized armies, but also frames the increase in an ambitious commercial strategy, with the F-35 "Lightning" as the main product. As an example, Poland: after reaching the required 2%, this country announced the purchase of 35 F-35s and their software and technical support for $6.5 billion. Thus, the US was able to cope with the losses caused by the breakdown of the agreement with Turkey after the Ottomans acquired the Russian S-400 system. With this acquisition, Poland jo ins the club of seven other NATO members with this aircraft, facing the commercial offensive of the European producer bloc to continue selling "Eurofighter" packages and, especially, the recent Future Combat Air System (led by Airbus and Dassault), of which Spain is a member. Europe wants to create a strong Defense Industry community for reasons of self-sufficiency and to compete in the markets against the US industry, so we are facing a "mini" trade war between allied countries.

c) Regarding Turkey, the most uncomfortable member of NATO, there was a clear negative feeling. It is an unreliable ally, which is attacking other allies in Operation Inherent Resolve such as the Kurdish militias, considered terrorists by the Ankara government. Hovering over the leaders present in London was the fear of a possible invocation of article 5 of the Washington Treaty by Turkey calling for an active confrontation in Syria. NATO does not have much choice, for if it does not stand up to Erdogan, it would be pushing him completely into the Russian orbit.

London Declaration

The final statement of the summit showed a change of focus within the Alliance: until now, Russia was the main concern and, although it is still a priority, China is taking its place. The Declaration can be divided into three blocks.

1) The first block functions as an emergency stopgap, with the aim of satisfying the most discordant voices and creating a picture of apparent seamless union. In its first point, the member states reaffirm the commitment of all countries to the common values they share, citing democracy, individual freedom, human rights and the rule of law. As a gesture to Turkey, article 5 is mentioned as the cornerstone of the North Atlantic Treaty. It is clear that, at least in the short to medium term, Western countries want to keep Turkey as a partner, being willing to compromise in small gestures.

Further on, the Alliance insists on the need to "continue to strengthen the capabilities, both of member states and collectively, to resist all forms of attack". With regard to the 2% goal , which is paramount for the US and the top spending states, it is stated that good progress is being made, but that "more must and will be done".

2) The next block goes into a purely strategic and less political subject . The Alliance notes that the current international system is under attack by state and non-state actors. It highlights the threat posed by Russia to the Eurasian region and introduces irregular immigration as a source of instability.

With regard to this stabilization, the Alliance's main guidelines will be to ensure a long-term presence in Afghanistan, a stronger partnership with the UN, as well as a direct NATO-EU partnership , and to increase its global presence and work at all levels. The Alliance wants to increase its global presence and its work at all levels. The forthcoming accession of North Macedonia as the 30th member of the Alliance is sample clear message to Russia that there is no place in Europe for its influence.

Clearly, for NATO we find ourselves in 4th generation conflicts, with the use of cyber and hybrid warfare. The commitment to 360° security within the Alliance is mentioned. The Alliance is aware of the changing realities of the battlefield and the international arena, and sample its commitment to adapt and update its capabilities.

3) As a third block, for the first time China is mentioned directly as an issue requiring joint decisions. The leadership that China is assuming in the field of communications and internet, especially with 5G technology, is of deep concern in the Atlanticist bosom. In an operating environment where cyberwarfare and hybrid warfare will change the way we deal with conflict, we want to ensure the resilience of societies that are completely dependent on technology, especially by protecting critical infrastructure (government buildings, hospitals, etc.) and energy security. In London, the importance of developing our own systems so as not to depend on those provided by countries that could use them against consumers was also proclaimed, as well as the need to increase offensive and defensive capabilities in the cyber environment. It was recognized that China's growing influence in the international arena presents both opportunities and risks, and that it is an issue that must be closely and permanently monitored.

The Document ends with a statement of intent: "In times of challenge, we are stronger as an Alliance and our people are more secure. Our togetherness and commitment to each other has guaranteed our freedoms, values and security for 70 years. We act today to ensure that NATO guarantees these freedoms, values and security for generations to come."

Although it was a bittersweet summit, with many disagreements and unfortunate comments, the reality is that, outside of politics, the Alliance is prepared. It is aware of the threats it faces, both internal and external. It knows the realities of today's world and wants to act accordingly, with a greater and more lasting Degree involvement. Although words have often remained on paper, this Declaration and this Summit show an Alliance that, with its particularities, is ready to face the challenges of the 21st century; its old ghosts, such as Russia, and its new threats, such as China.

UN led vs. non-UN led post-conflict government building

March 28, 2020

WORKING PAPER / María del Pilar Cazali

ABSTRACT

Government building in Africa has been an important issue to deal with after post- independence internal conflicts. Some African states have had the support of UN peacekeeping missions to rebuild their government, while others have built their government on their own without external help. The question this article looks to answer is what method of government building has been more effective. This is done through the analysis of four important overall government building indicators: rule of law, participation, human rights and accountability and transparency. Based on these indicators, states with non-UN indicators have had a more efficient government building especially due to the flexibility and freedom they've had to do it in comparison with states with UN intervention due to the UN's neo-liberal view and their lack of contact with locals.

Download the document [pdf. 431K]

Download the document [pdf. 431K]

The Trump Administration's Newest Migration Policies and Shifting Immigrant Demographics in the USA

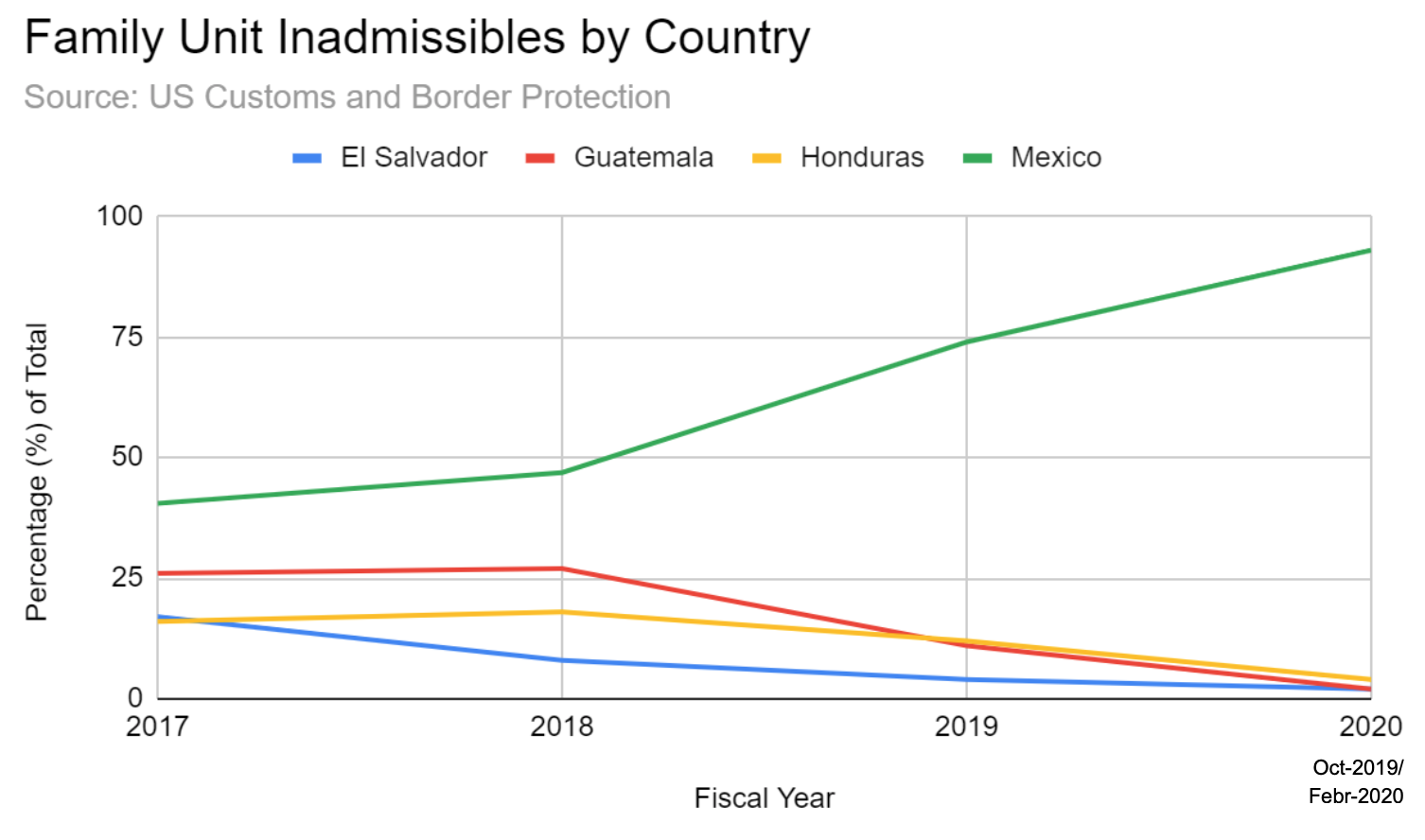

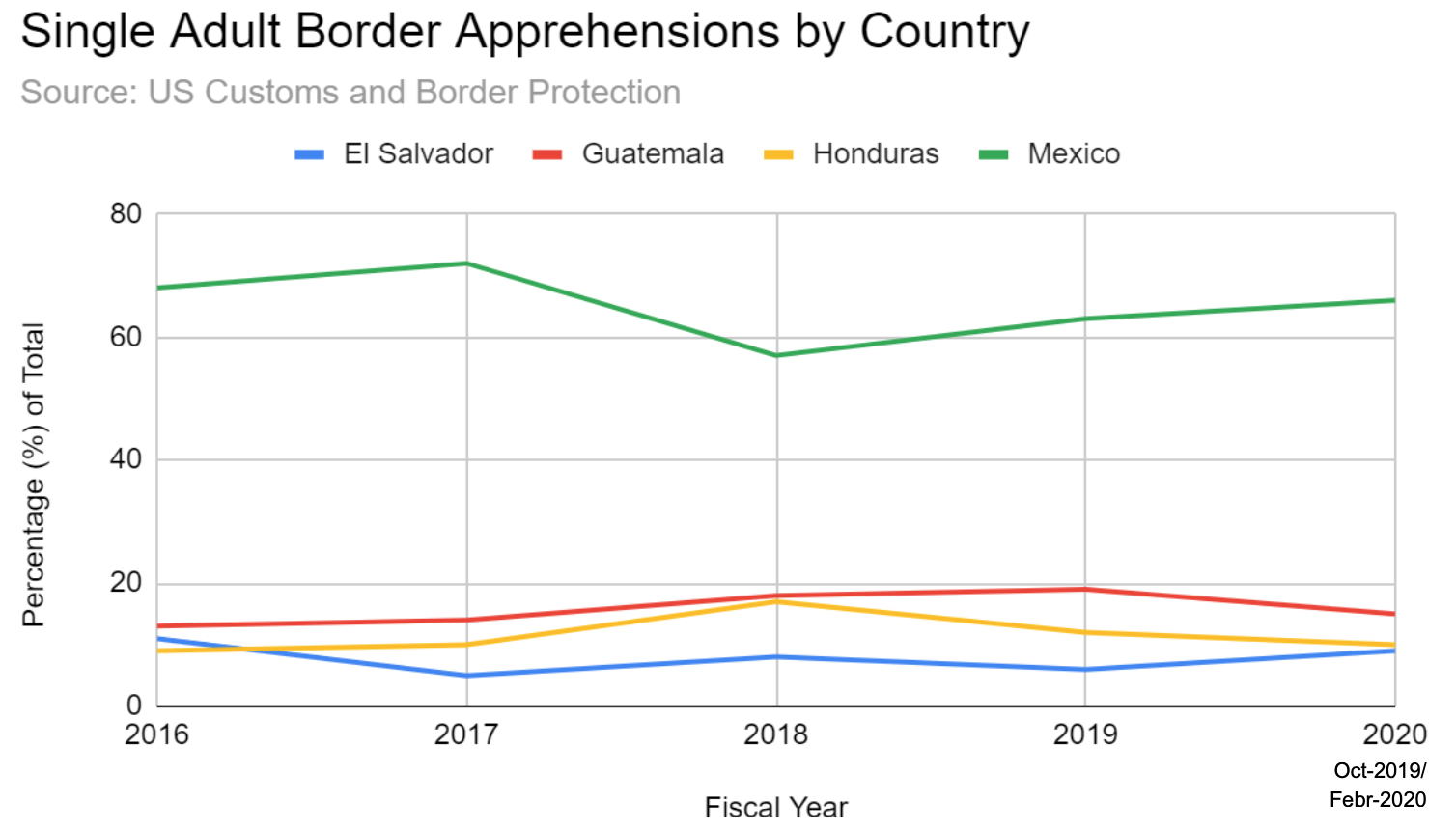

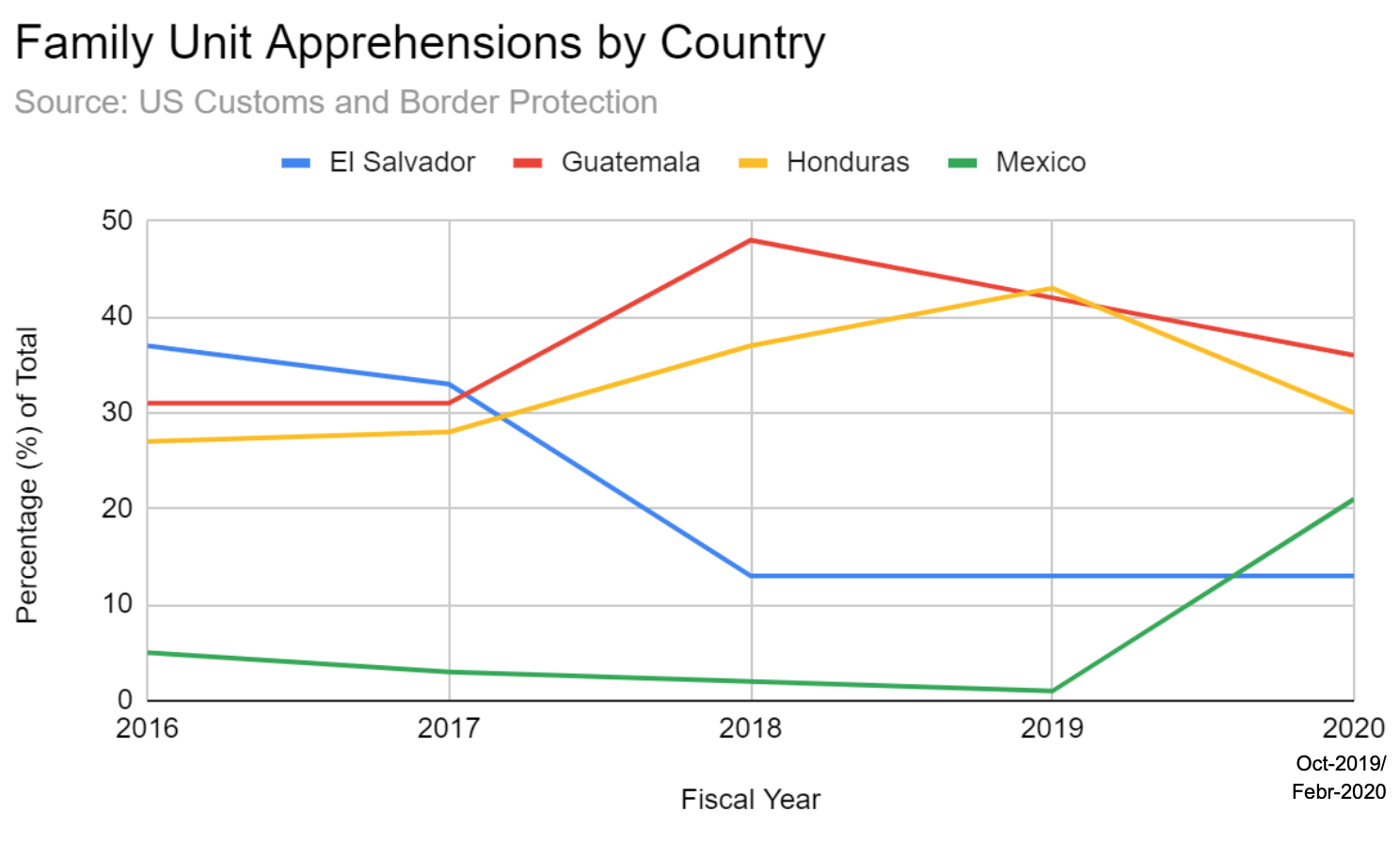

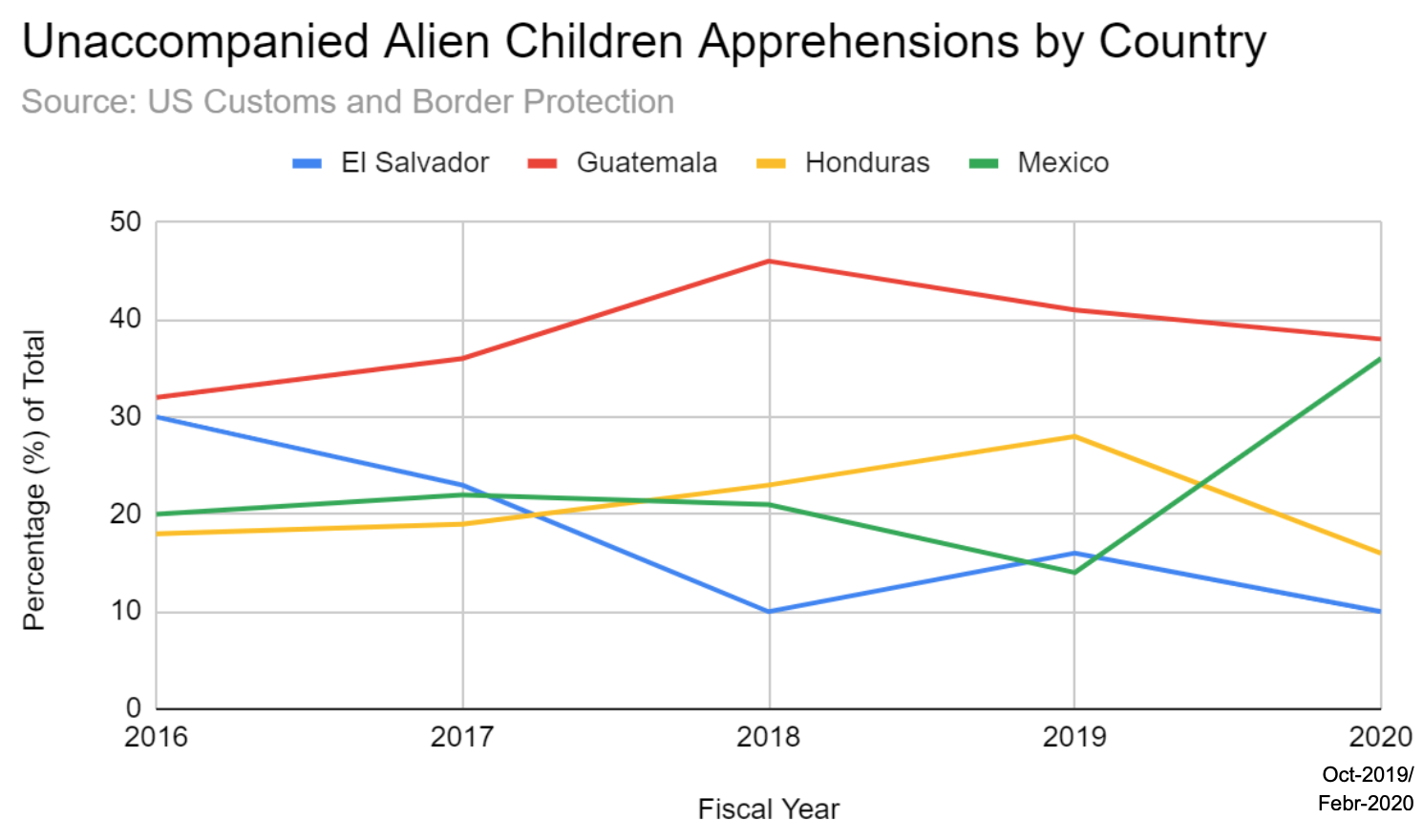

New Trump administration migration policies including the "Safe Third Country" agreements signed by the USA, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have reduced the number of migrants from the Northern Triangle countries at the southwest US border. As a consequence of this phenomenon and other factors, Mexicans have become once again the main national group of people deemed inadmissible for asylum or apprehended by the US Customs and Border Protection.

![An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov]. An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov].](/documents/10174/16849987/migracion-mex-blog.jpg)

▲ An US Border Patrol agent at the southwest US border [cbp.gov].

ARTICLE / Alexandria Casarano Christofellis

On March 31, 2018, the Trump administration cut off aid to the Northern Triangle countries in order to coerce them into implementing new policies to curb illegal migration to the United States. El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala all rely heavily on USAid, and had received 118, 181, and 257 million USD in USAid respectively in the 2017 fiscal year.

The US resumed financial aid to the Northern Triangle countries on October 17 of 2019, in the context of the establishment of bilateral negotiations of Safe Third Country agreements with each of the countries, and the implementation of the US Supreme Court's de facto asylum ban on September 11 of 2019. The Safe Third Country agreements will allow the US to 'return' asylum seekers to the countries which they traveled through on their way to the US border (provided that the asylum seekers are not returned to their home countries). The US Supreme Court's asylum ban similarly requires refugees to apply for and be denied asylum in each of the countries which they pass through before arriving at the US border to apply for asylum. This means that Honduran and Salvadoran refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in both Guatemala and Mexico before applying for asylum in the US, and Guatemalan refugees would need to apply for and be denied asylum in Mexico before applying for asylum in the US. This also means that refugees fleeing one of the Northern Triangle countries can be returned to another Northern Triangle country suffering many of the same issues they were fleeing in the first place.

Combined with the Trump administration's longer-standing "metering" or "Remain in Mexico" policy (Migrant Protection Protocols/MPP), these political developments serve to effectively "push back" the US border. The "Remain in Mexico" policy requires US asylum seekers from Latin America to remain on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border to wait their turn to be accepted into US territory. Within the past year, the US government has planted significant obstacles in the way of the path of Central American refugees to US asylum, and for better or worse has shifted the burden of the Central American refugee crisis to Mexico and the Central American countries themselves, which are ill-prepared to handle the influx, even in the light of resumed US foreign aid. The new arrangements resemble the EU's refugee deal with Turkey.

These policy changes are coupled with a shift in US immigration demographics. In August of 2019, Mexico reclaimed its position as the single largest source of unauthorized immigration to the US, having been temporarily surpassed by Guatemala and Honduras in 2018.

US Customs and Border Protection data indicates a net increase of 21% in the number of Unaccompanied Alien Children from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador deemed inadmissible for asylum at the Southwest US Border by the US field office between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February). All other inadmissible groups (Family Units, Single Adults, etc.) experienced a net decrease of 18-24% over the same time period. For both the entirety of fiscal year 2019 and fiscal year 2020 through February, Mexicans accounted for 69 and 61% of Unaccompanied Alien Children Inadmissible at the Southwest US border respectively, whereas previously in fiscal years 2017 and 2018 Mexicans accounted for only 21 and 26% of these same figures, respectively. The percentages of Family Unit Inadmisibles from the Northern Triangle countries have been decreasing since 2018, while the percentage of Family Unit Inadmisibles from Mexico since 2018 has been on the rise.

With asylum made far less accessible to Central Americans in the wake of the Trump administration's new migration policies, the number of Central American inadmisibles is in sharp decline. Conversely, the number of Mexican inadmisibles is on the rise, having nearly tripled over the past three years.

Chain migration factors at play in Mexico may be contributing to this demographic shift. On September 10, 2019, prominent Mexican newspaper El discussion published an article titled "Immigrants Can Avoid Deportation with these Five Documents." Additionally, The Washington Post cites the testimony of a city official from Michoacan, Mexico, claiming that a local Mexican travel company has begun running a weekly "door-to-door" service line to several US border points of entry, and that hundreds of Mexican citizens have been coming to the municipal offices daily requesting documentation to help them apply for asylum in the US. Word of mouth, press coverage like that found in El discussion, and the commercial exploitation of the Mexican migrant situation have perhaps made migration, and especially the claiming of asylum, more accessible to the Mexican population.

US Customs and Border Protection data also indicates that total apprehensions of migrants from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador attempting illegal crossings at the Southwest US border declined 44% for Unaccompanied Alien Children and 73% for Family Units between fiscal year 2019 (through February) and fiscal year 2020 (through February), while increasing for Single Adults by 4%. The same data trends show that while Mexicans have consistently accounted for the overwhelming majority of Single Adult Apprehensions since 2016, Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions until the past year were dominated by Central Americans. However, in fiscal year 2020-February, the percentages of Central American Family Unit and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions have declined while the Mexican percentage has increased significantly. This could be attributed to the Northern Triangle countries' and especially Mexico's recent crackdown on the flow of illegal immigration within their own states in response to the same US sanctions and suspension of USAid which led to the Safe Third Country bilateral agreements with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

While the Trump administration's crackdown on immigration from the Northern Triangle countries has effectively worked to limit both the legal and illegal access of Central Americans to US entry, the Trump administration's crackdown on immigration from Mexico in the past few years has focused on arresting and deporting illegal Mexican immigrants already living and working within the US borders. Between 2017 and 2018, ICE increased workplace raids to arrest undocumented immigrants by over 400% according to The Independent in the UK. The trend seemed to continue into 2019. President Trump tweeted on June 17, 2019 that "Next week ICE will begin the process of removing the millions of illegal aliens who have illicitly found their way into the United States. They will be removed as fast as they come in." More deportations could be leading to more attempts at reentry, increasing Mexican migration to the US, and more Mexican Single Adult apprehensions at the Southwest border. The Washington Post alleges that the majority of the Mexican single adults apprehended at the border are previous deportees trying to reenter the country.

Lastly, the steadily increasing violence within the state of Mexico should not be overlooked as a cause for continued migration. Within the past year, violence between the various Mexican cartels has intensified, and murder rates have continued to rise. While the increase in violence alone is not intense enough to solely account for the spike that has recently been seen in Mexican migration to the US, internal violence nethertheless remains an important factor in the Mexican migrant situation. Similarly, widespread poverty in Mexico, recently worsened by a decline in foreign investment in the light of threatened tariffs from the USA, also plays a key role.

In conclusion, the Trump administration's new migration policies mark an intensification of long-standing nativist tendencies in the US, and pose a potential threat to the human rights of asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border. The corresponding present demographic shift back to Mexican predominance in US immigration is driven not only by the Trump administration's new migration policies, but also by many other diverse factors within both Mexico and the US, from press coverage to increased deportations to long-standing cartel violence and poverty. In the face of these recent developments, one thing remains clear: the situation south of the Rio Grande is just as complex, nuanced, and constantly evolving as is the situation to the north on Capitol Hill in the USA.

Chinese companies develop four mining projects on the island; Trump offered to buy it

The melting of the Arctic ice opens up new maritime routes and gives special value to certain territories, such as Iceland and especially Greenland, whose enormous size also conceals great natural resources. Chinese mining companies have been present in the "Green Earth" since 2008; the Danish government has sought to curb Beijing's increasing influence by directly taking over the construction of three airports instead of having them placed under Chinese management . Copenhagen has a veiled fear that China will encourage Greenlandic independence, while the White House has offered to buy the island, as it has tried to do at other times in history.

![Population of Oqaatsut, on the east coast of Greenland [Pixabay]. Population of Oqaatsut, on the east coast of Greenland [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/groenlandia-blog.jpg)

▲ Population of Oqaatsut, on the east coast of Greenland [Pixabay].

March 20, 2020

article / Jesús Rizo Ortiz

Greenland is the largest island in the world, with more than 2 million square kilometers, while its inhabitants are less than 60,000, making it the least densely populated territory in the world. This reality, together with the natural wealth still to be exploited and the geographical location, give this Green Earth a great geostrategic importance. In addition, global warming and the struggle for the new world order between the USA, China and Russia place this territory dependent on Denmark at the center of geopolitical dynamics for the first time in its history.

Due to the melting of the Arctic Ocean, new communication routes are emerging between the American, European and Asian continents. These routes, although they will remain subject to limitations in the future, are becoming more and more accessible and for longer periods of time throughout the year. Greenland is a strategic control and supply point for both the Northern route (which follows the northern contour of Russia) and the Northwest route (which crosses the northern islands of Canada), not only in the case of goods and commercial ships, but also in terms of security, as the melting of the ocean ice significantly shortens the distances between the main international players.

Greenland's geographical position is a core topic, but also what it contains under the ice that covers 77% of its surface. It is estimated that 13% of the world's oil reserves are found in Greenland, as well as 25% of the so-called rare earths (neodymium, dysprosium, yttrium...), which are essential in the production of new technologies.

Interest from China and the U.S.

The prospects opened up by the increased possibility of navigation through the Arctic have led the Arctic powers to develop their strategies. But also China, interested in a Polar Silk Road, has sought ways to be present in the Arctic circle, and has found a gateway in Greenland.

China's foreign policy is largely focused on the execution of projects in areas where its financial power is needed, and it is doing so in places in need of development , such as Africa and Latin America. This subject action is also being pursued in Greenland, where Chinese companies have been present since 2008. The main Danish political parties view this connection with Beijing with reticence, but the reality is that many of the Greenlandic population, more than 80% of whom are of Inuit origin, value positively the possibilities for local development opened up by Chinese investments. That different perspective was especially evident when in 2018 the government of this self-governing territory promoted three international airports (expansion of the one in the capital, Nuuk, and construction in the tourist sites of Ilulimat and Qaqortog), which together represented the largest public works contracting in its history. Although an offer from the state-owned construction company CCCC was quickly received from China, Copenhagen finally decided to contribute Danish public funds and participate in the ownership of the airports, given the misgivings about the Chinese initiative.

China is present, in any case, in four previous projects, related to mining and managed by both state-owned and private companies, all following the geopolitical purposes of the Chinese government, whose Ministry of Information Technology and Industry has expressed its interest in the activity in Greenland. These four projects are the Kvanefjeld project for the extraction of rare earths, mainly financed by Shenghe Resources; the Iusa project for iron ore extraction, fully financed by General Nice; the Wegener Halvø project for copper extraction, supported by Jiangxi Zhongrun following an agreement with Nordic Mining in 2008; and finally, the Citronen Base Metal project, in the position of China Nonferrus Metal Industry's Foreign Engineering and Construction (NFC).

The United States is no slouch in its interest in Greenland. As early as the 1860s, U.S. President Andrew Johnson highlighted Greenland's importance in terms of resources and strategic position. Almost a century later, in 1946, Harry Truman offered the Danish government to buy Greenland for $100 million in gold. Although the offer was rejected by Denmark, Denmark did accept the establishment in 1951 of a U.S. air base at Thule. This is the northernmost military base in the world, which was a core topic during the Cold War and is still in operation today. This base gives the US an advantage not only in the face of the commercial opening of new sea crossings, but also in the face of a hypothetical Sino-Russian coalition seeking to dominate the Northern route. In other words, given the double aspect of Greenland's importance (natural resources and security), it is understandable that someone as unconventional as Donald Trump has once again suggested the possibility of buying the immense island, something that Copenhagen has declined.

![Projected pathways through the Arctic; the top row corresponds to the melting that could occur with low emissions, the bottom row in the case of high emissions [Arctic Council]. Projected pathways through the Arctic; the top row corresponds to the melting that could occur with low emissions, the bottom row in the case of high emissions [Arctic Council].](/documents/10174/16849987/groenlandia-mapa.jpg)

Projected pathways through the Arctic; the top row corresponds to the melting that could occur with low emissions, the bottom row in the case of high emissions [Arctic Council].

At the center of a 'Great Game

Apart from the current unfeasibility of such an operation without taking into account, among other things, the will of the population, it is true that a Great Game is taking place among the main international players to count Greenland among their geostrategic cards.