The nascent English kingdom was consolidated in civil service examination to power on the other side of the English Channel, giving rise to a particularism that is particularly alive today.

With no turning back now, once Brexit has been consummated, England is seeking to establish a new relationship with its European neighbors. Its departure has not been seconded by any other country, which means that London has to come to terms with a European Union that remains a bloc. Despite the drama with which many Europeans have welcomed Britain's farewell, this is yet another chapter in the complex relationship that a large island has with the continent to which it is close. Island and continent continue where geography has placed them -at a distance of particular value- and will possibly reproduce vicissitudes already seen throughout their mutual history.

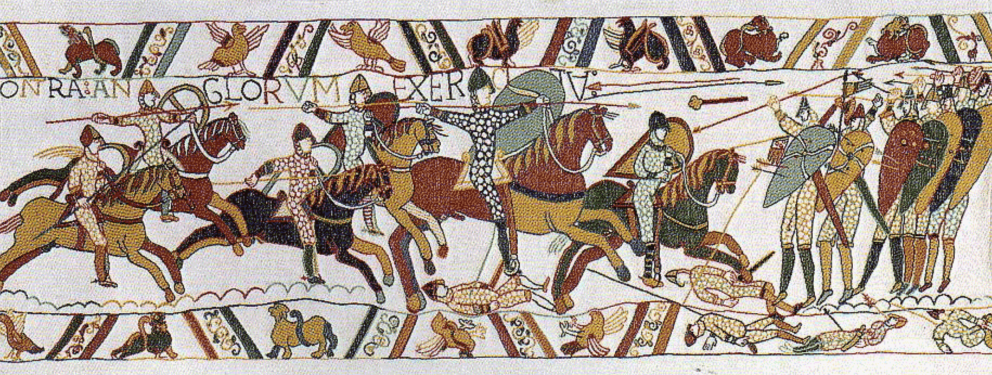

Fragment of the Bayeux tapestry, illustrating the battle of Hastings in 1066.

article / María José Beltramo

The result of the 2016 referendum on Brexit may have come as a surprise, as the abrupt manner in which the United Kingdom finally and effectively left the European Union on December 31, 2020, has undoubtedly come as a surprise. However, what we have seen is not so alien to the history of the British relationship with the rest of Europe. If we go back centuries, we can see a geopolitical patron saint that has been repeated on other occasions, and also today, without having to speak of determinism.

Although it is worth mentioning some previous moments in the relationship of the insular Britannia with the continent next to which it is located, such as the period of Romanization, the gestation of the patron saint that at the same time combines linkage and distancing, or even rejection, we can perhaps place it at the beginning of the second millennium, when from Norman invasions that cross the English Channel the nascent kingdom of England is consolidated precisely against the power of the other shore.

England in Norman times

Normandy became a political entity in northern France when in 911, after Viking invasions, the Norman chief Rolon reached an agreement with the Frankish king that guaranteed him the territory in exchange for its defense[1]. Normandy became a duchy and gradually adopted the Frankish feudal system, facilitating the gradual integration of both peoples. This intense relationship would eventually lead to the full incorporation of Normandy into the kingdom of France in 1204.

Before the progressive Norman dissolution, however, the Scandinavian people settled in that part of northern France carried their particular character and organizational capacity, which ensured their independence for several centuries, across the English Channel.

The Norman-English relationship began in 1066 with the Battle of Hastings, in an invasion that led to the Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror, being crowned king of England in London. The arrival of the Normans had several consequences. From the political point of view, they introduced the islands into the European relations of the time and adapted English feudalism to Norman feudalism, a mixture that would lay the instructions for the future English parliamentarism. In terms of Economics, the Normans demonstrated their Scandinavian organizational capacity in the reorganization of productive activities. In their different conquests, the Normans knew how to take advantage of the best of each system and adapt it to their culture and needs, and so it happened in England, where they developed a particular idiosyncrasy.

From this contact with the continent, England began to consolidate as a monarchy without leaving its link with the Duchy of Normandy. However, with its strengthening after the fall of the Plantagenets in France, England gained the momentum it lacked to finally become an independent kingdom, completely separated from the continent, detached from a Normandy with a weak and critical lineage. In fact, the absorption of the Norman duchy by the kingdom of France facilitated the development and consolidation of the English monarchy as an independent and strong entity[2].

The separation with respect to the European continent refers us to Ortega y Gasset's analysis of European decadence and the moral crisis it is going through[3]. The continental powers, being in a status of geographical continuity, and therefore in greater contact, are more likely to spread their status among themselves and to be dominated by another major power. England, having broken the bridge of feudal ties that connected it with the rest of Europe, finds no difficulty in distancing itself when it sees fit, always in its own interests, something we see repeated several times throughout its history. This is especially evident in the vicissitudes that punctuate the United Kingdom's relationship with the continent throughout the final decades of the second millennium.

English status since 1945

The Second World War greatly weakened the United Kingdom, not only economically, but also as an empire. In the subsequent process of decolonization, London lost possessions in Asia and Africa; moreover, the Suez Canal conflict confirmed its decline as a key player, precisely at the hands of the United States, which had replaced it as the world's leading power. The post-war confrontation with the Soviet Union and the American presence in Europe meant that the transatlantic relationship was no longer based on the preferential link that Washington had with England, so the role of the British also diminished[4].

In 1957, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg created the European Economic Community (EEC). Conservative Harold MacMillan, British Prime Minister from 1957 to 1963, refused to include the United Kingdom in the initiative, but aware of the need to revitalize British Economics and "the difficulty of maintaining a policy that was alien to European interests", he promoted the creation in 1959 of the EFTA (European Free Trade Association) together with Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, Austria and Portugal.

The Common Market proved to be a success and in 1963 the United Kingdom considered joining it, but was blocked by de Gaulle's France. In 1966, the British again submitted their application, but it was again rejected by De Gaulle. The French general's conception of Europe did not include the Atlantic bloc, he still thought of building Europe on a Franco-German axis.

In the 1970s there was a directional shift in European politics. The British Conservatives won the 1970 elections and in 1973 their country joined the EEC. The international economic crisis, which was particularly difficult in the United Kingdom, prompted the Labour Party, back in power, to propose a review of the conditions of membership and Premier Harold Wilson called a referendum in 1975: 17 million Britons wanted to remain (67% of voters) compared with only 8 million who called for a first Brexit.

However, when the European Monetary System (EMS) was launched in 1979 to equalize currencies and achieve "economic convergence," the United Kingdom decided not to join this voluntary agreement . Europe was experiencing a gradual economic boom, but British Economics was not keeping pace, which partly led to the early elections of 1979. These were won by the Conservatives with Margaret Thatcher, who remained in Downing Street until 1990. The Thatcher revolution "marked the way out of the crisis of the 1970s". In 1984, London reduced its contribution to EU funds and Thatcher, who was very reluctant to accept EU budgets and other procedures that reduced national sovereignty, again asked for a review of the agreements.

In 1985 the Schengen Agreements were signed (the opening of borders between certain countries generating a kind of much wider second border), which came into force ten years later. Again, the UK stayed out of it. As was also the case in relation to the euro, when the single currency came into effect in 2002, maintaining the pound sterling to this day.

Immigration from Central and Eastern European countries, following the 2004 EU enlargement, admitted by the Labour Party's Tony Blair, and the acceleration of financial harmonization mechanisms following the 2008-2011 crisis, faced with displeasure by the Conservative David Cameron, provided arguments for the anti-EU speech in the United Kingdom. This led to the rise of the anti-European UKIP and the assumption of its postulates by broad Tory sectors, finally amalgamated by the controversial personality of Boris Johnson.

In an interview with the BBC Johnson referred in 2016 to many of the arguments used in favor of Brexit, such as the dialectical vision that the United Kingdom has of its relationship with the continent or the fear of losing sovereignty and the dissolution of its own profile in the European magma. The premier returned to these ideas in his message to the British people as the country was about to begin its last year in the EU. His words were in some ways an echo of a centuries-old tug-of-war.

Repeating patterns

As we have seen, England has always maintained its own rhythm. Its geographical separation from the continent - far enough away to be able to preserve a particular dynamic, but also close enough to fear a threat, which sometimes proved to be effective - determined the distinctly insular identity of the British and their attitude towards the rest of Europe.

We are dealing with a power that throughout history has always sought to maintain its national sovereignty at all costs and whose geopolitical imperative has been to prevent the continent from being dominated by a rival great power (the perception, during the management the 2008 crisis, that Germany was once again exercising a certain hegemony in Europe may have fueled the Brexit).

Perhaps in the medieval period we cannot link this to a meditated political strategy, but we do see how, involuntarily and circumstantially, we can see how, from the very beginning, there are certain conditions that favor the distancing of the island from the continent, although without losing contact in a radical way. In more recent history we observe this same distant attitude, this time premeditated, with the pursuit of interests focused on the search for economic prosperity and the maintenance of both its global influence and its national sovereignty.

[1] Charles Haskins, The Normans in European History (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1915).

[2] Yves Lacoste, Géopolitique : La longue histoire d'aujourd'hui (Paris: Larousse, 2006).

[3] José Ortega y Gasset, La rebelión de las masas (Madrid: Alianza publishing house, 1983).

[4] José Ramón Díez Espinosa et al., Historia del mundo actual (desde 1945 hasta nuestros días), (Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid, 1996).