27% of Latin America's total private wealth is held in territories that offer favourable tax treatment.

Latin America is the world region with the highest percentage of private offshore wealth. The proximity of tax havens, in various countries or island dependencies in the Caribbean, can facilitate the arrival of this capital, some of which is generated illicitly (drug trafficking, corruption) and all of which evades national tax institutions with little supervisory and coercive force. Latin America lost 335 billion dollars in taxes in 2017, which represented 6.3% of its GDP.

![Caribbean beach [Pixabay]. Caribbean beach [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/paraiso-fiscal-blog.jpg)

▲ Caribbean beach [Pixabay].

article / Jokin de Carlos Sola

The natural wealth of Latin American countries contrasts with the precariousness of the economic status of a large part of their societies. Lands rich in oil, minerals and primary goods sometimes fail to feed all their citizens. One of the reasons for this deficiency is the frequency with which companies and leaders tend to evade taxes, driving capital away from their countries.

One of the reasons for the tendency to evade taxes is the large size of the Economics underground and the shortcomings of states in implementing tax systems. Another is the nearby presence of tax havens in the Caribbean, which have historically been linked to the UK. These territories with beneficial tax characteristics have attracted capital from the continent.

History

The history of tax evasion is a long one. Its relationship with Latin America and the British Caribbean archipelagos, however, has its origins in the fall of the British Empire.

From 1945 onwards, Britain gradually began to lose its colonial possessions around the world. The financial effect was clear: millions of pounds were lost or taken out of operations across the empire. To cope with this status and to be able to maintain their global financial power, the bankers in the City of London thought of creating fields of action outside the jurisdiction of the Bank of England, from where bankers from all over the world (especially Americans) could also operate in order to avoid their respective national regulations. A new opportunity then arose in the British overseas territories, some of which did not become independent, but maintained their links, albeit loose, with the United Kingdom. This was the case in the Caribbean.

In 1969 the Cayman Islands created the first banking secrecy legislation. It was the first overseas territory to become a tax haven. From offices established there, City banks built up networks of operations unregulated by the Bank of England and with little local oversight. Soon other Caribbean jurisdictions followed suit.

Tax havens

The main tax havens in the Caribbean are British Overseas Territories such as the Cayman Islands, the Virgin Islands and Montserrat, or some former British colonies that became independent, such as the Bahamas. These are islands with small populations and a small Economics . Many of the politicians and legislators in these places work for the British financial sector and ensure secrecy within their territories.

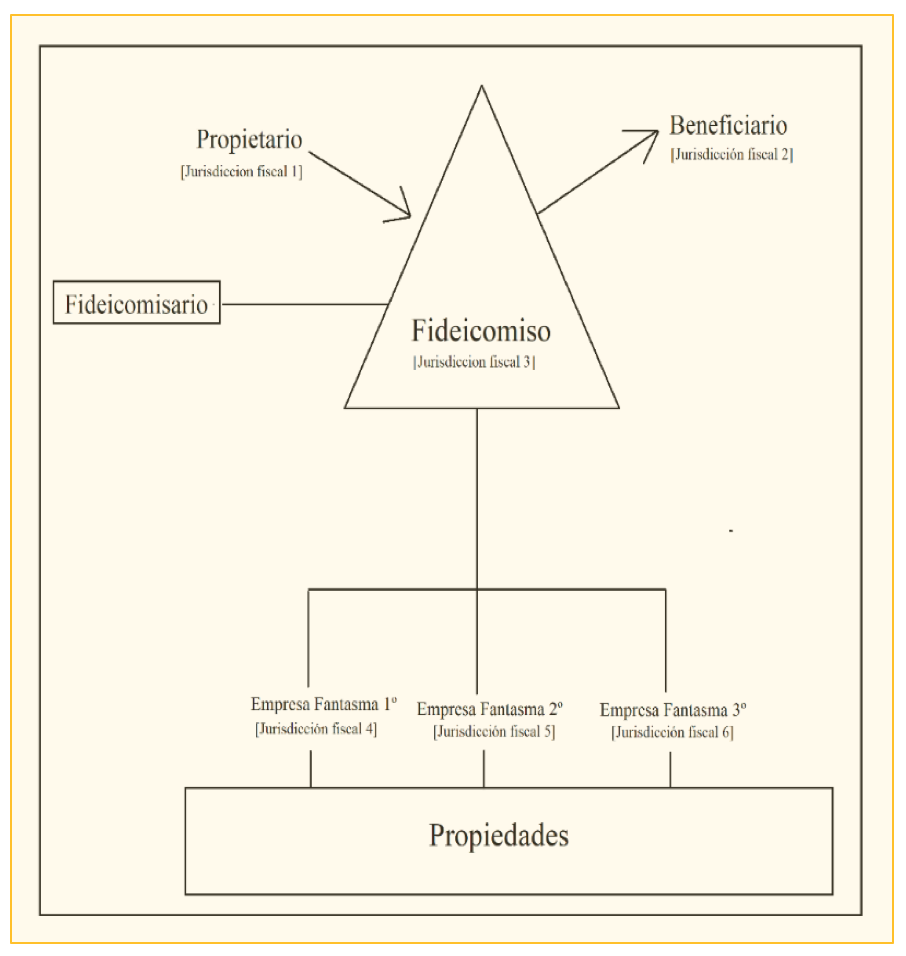

Unlike other locations that can also be considered tax havens, the British-influenced islands in the Caribbean offer a second level of secrecy in addition to the legal one: the trust. Most of those who hold assets in companies established in these territories do so through trusts. Under this system, the beneficiary holds his assets (shares, property, companies, etc.) in a trust which is administered by a trustee. These elements (trust, beneficiary, trustee, shell companies, etc.) are distributed in various Structures linked to different Caribbean jurisdictions. Thus, a trust may be established in one jurisdiction, but its beneficiaries may be in another, the trustee in a third, and the shell companies in a fourth. This is a subject of Structures that is almost impossible for governments to dismantle. This is why when overseas governments agree to share banking information, under pressure from Washington or Brussels, it is of little use because of the secrecy structure itself.

Impact in Latin America

Bank secrecy legislation emerged in Latin America with the goal aim of attracting legally obtained capital. However, during the 1970s and 1980s, this protection on data of current accounts also attracted capital obtained through illicit means, such as drug trafficking and corruption.

During those years, drug lords such as Pablo Escobar used the benefits of the Cayman Islands and other territories to hide their fortunes and properties. On the other hand, several Latin American dictatorships also used these mechanisms to hide the enrichment of their leaders through corruption or even drugs, as was the case with Panama's Manuel Noriega.

Over time, the international community has increased its pressure on tax havens. In recent years the authorities in the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas have made efforts to ensure that their secrecy Structures is not used to launder money for organised crime, but not all territories considered tax havens have done the same.

These opaque networks are used by a considerable part of Latin America's large fortunes. Twenty-seven per cent of Latin America's total private wealth is deposited in countries that offer favourable tax treatment, making it the region with the highest proportion of private capital in these places in the world, according to a 2017 study by the Boston Consulting Group ( agreement ). According to this consultancy firm, this diversion of private wealth is greater in Latin America than in the Middle East and Africa (23%), Eastern Europe (20%), Western Europe (7%), Asia-Pacific (6%) and the United States and Canada (1%).

Tax havens are the destination of a part that is difficult to pinpoint of the total of 335 billion dollars subject to tax evasion or avoidance in the region in 2017, a figure that constituted 6.3% of Latin American GDP (4% lost in personal income tax and 2.3% in VAT), as specified in ECLAC's report Fiscal Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2019. This UN economic commission for the region highlights that on average Latin American countries lose more than 50% of their income tax revenues.

The London connection

There have been various theories about the role played by London in relation to tax havens. These theories coincide in presenting a connection of interests between the opaque companies and the City of London, in a network of complicity in which even the Bank of England and the British government could have been involved.

The most important one was expressed by British author Nicholas Shaxson in the book Treasure Island. The thesis was later developed by the documentary film Spiders Web, produced by the Tax Justice Network, whose founder, John Christiansen, worked as advisor for the government of Jersey, which is a special jurisdiction.

The City of London has a separate administration, elected by the still-existing guilds, which represent the City's commercial and banking class . This allows financial operations in this area of the British capital to partially escape the control of the Bank of England and government regulations. A City that is attractive to foreign capital and prosperous is of great benefit to the UK's Economics , as its activity accounts for 2.4% of the country's GDP.

British sovereignty over the overseas territories that serve as tax havens sometimes leads to accusations that the UK is complicit with these financial networks. Downing Street responds that these are territories that operate with a great deal of autonomy, even though London sets the governor, controls foreign policy and has veto power over legislation passed in these places.

Moreover, it is true that the UK government has in the last decade supported greater international coordination to increase scrutiny of tax havens, forcing the authorities there to submit relevant tax information, although the structure of the trusts still works against transparency.

Correct the status

Latin America's problems with tax evasion may be more related to the fragility of its own tax institutions than to the presence of tax havens close to the American continent. At the same time, some tax havens have benefited from political instability and corruption in Latin America.

The effects of domestic capital flight to these places of special tax regimes are clearly negative for the countries of the region, depriving them of increased economic activity and revenue-raising possibilities, and hampering the state's ability to undertake the necessary improvement of public services.

It is therefore imperative that certain corrective policies are put in place. At the national policy level, mechanisms should be put in place to prevent tax evasion and avoidance. At the same time, at the international level, diplomatic initiatives should be shaped to put an end to the Structures of trusts. The OAS offers, in this sense, an important negotiating framework not only with certain overseas territories, but also with its own metropolises, since these, as is the case of the United Kingdom, are permanent observer members of the hemispheric organisation.