Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Central Europe and Russia .

Poland-Germany struggle to gain influence in the European region between the Baltic, the Adriatic and the Black Sea

The latest summit of the Three Seas Initiative (TTI) was attended by the president of the European Commission, which sample was an endorsement from Brussels that did not seem complete until now. German representatives also attended attendance , although Germany is not part of the twelve-nation club of Central and Eastern European countries. Poland, backed by the United States, wants to lead the ongoing effort to reduce the region's energy dependence on Russian gas; in reaction, Germany has announced a timid bid to import liquefied gas from the US.

article / Paula Ulibarrena

On 17-18 September 2018, the third summit of the Three Seas Initiative took place in Bucharest, aiming at the economic development of the area of the European Union (EU) between the Baltic, Adriatic and Black Seas. The meeting was attended by nine heads of state, two presidents of national parliaments, a prime minister and a foreign minister, along with several senior European officials, led by European Commission President Jean-Claude Junker, and a large German representation, as well as US leaders.

The Three Seas Initiative (BABS-Initiative: Baltic, Adriatic, Black Sea) was launched in 2015 and consists of twelve countries: Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

According to the Polish Foreign Affairshigh school , the EU's initial reticence about the MTI seems to have been overcome, as the summit was endorsed by the European Commission and the European Parliament's Commissioner for Regional Policy. This recognises the role of the MTI in cohesion and in strengthening the EU.

The importance of energy supply

One of the main aspects that the ITM deals with is energy. Its goal is to have agile access to energy, but also to ensure supply from various points, so as not to depend on a single provider, and also to try to play a diversifying role in supplying other European regions. At present, its efforts are mainly focused on the so-called project BRUA, which aims to open up the possibility of transporting gas from the Caspian Sea area to Romania's southern border, and from there to Romania's north-western border with Hungary.

BRUA is an acronym for Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Austria, and aims to diversify the natural gas supply system in the region. "We are creating a distribution network ," said Miguel Arias Cañete, European Commissioner for Energy and Climate Change, "it is not just a big classical pipeline but small reverse flow pipelines that allow gas to be sent south, east, west, so the region will have more sources of energy and cheaper energy.

The BRUA pipeline would be, to some extent, a replacement for the failed project Nabucco. This project consisted of the development of a natural gas transport capacity between existing interconnection points with the natural gas transport networks of Bulgaria (at Giurgiu) and Hungary (Csanadpalota), through the construction of a new pipeline with a total length of 550 km, on the route Giurgiu-Podisor-Corbu-Hurezani-Hateg-Recas-Horia, and three compressor stations located along its route (at Corbu, Hateg and Horia). It planned to reach a gas flow of 4.4 million cubic metres per year in the direction of Hungary, and 1.5 million cubic metres to Bulgaria.

The BRUA pipeline will only account for a third of the flow that Nabucco would have provided, thus minimising the risk of market loss for Russia. The route, which crosses Romania from east to west and from north to south, is estimated to cost a total of €560 million. Romania anticipates that the Black Sea exploration activities of OMV Petrom ExxonMobil could lead to the finding of new natural gas fields. To this end, it is envisaged to extend the BRUA pipeline by a further 300 kilometres from Giurgiu to the Black Sea perimeters.

Germany sent its foreign minister to the summit as an observer. Germany's interest is to strengthen its economic presence in the eastern region of the EU in order to prevent the growing weight of China, secure its energy supply and play an important role in the network gas distribution within Europe, in a context of conflict over Russian gas supplies, and the dependence that this entails for European countries. The construction of the second North European pipeline, known as project NS2 (Nord Stream 2), which will carry liquefied gas from Vyborg (western Russia) to Greifswald on the Baltic coast of Germany, is currently being finalised. civil service examination This project has always been opposed by the United States, which dislikes the EU's energy dependence on Russia, which is why the US is inclined to promote the ITM as area of development and entrance of energy sources that are not dependent on Russia.

|

BRUA pipeline, marked in blue, and TANAP (Turkey) and TAP (connection to Greece) pipelines, both in black, on an image taken from Google Maps. |

Poland comes into play

Poland is aligning itself with the US and trying to reduce Eastern European countries' economic and energy dependence on Russia. But it is also trying to reduce Germany's weight in the region; this is reminiscent of the Intermarium that Poland promoted in the years between the two world wars. Poland's aim is to become a new gas distribution hub for the EU, where its ports would be used for the unloading of liquefied natural gas of US origin. These ports would be connected to the project BRUA, replacing Ukraine as entrance of gas to the EU and in turn replacing Russian gas with US gas (9).

Precisely this project of the ITM, together with pressure from the US president, has provoked a reaction from Berlin. German Chancellor Angela Merkel counterattacked in October with the advertisement that Germany is once again opening the door to US gas by deciding to co-finance the construction of a 500 million euro liquefied natural gas ship terminal in the north of the country. This would strengthen Germany's alliance with the US, but could also reduce its dependence on nuclear energy and greenhouse gas emissions.

The TTI projects are financed by a financial fund provided by six of the member states (Croatia, Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Latvia), but open to the participation of all the countries that make up the group. Its goal is to provide financial support for the development of trans-national infrastructures in which at least three ITM member states participate. The institutional contribution exceeds 5 billion euros, and aims to attract external investment, from private funds, to strengthen the fund itself. With a thirty-year perspective, the aim is to exceed 100 billion euros.

![Warsaw downtown towers [Pixabay]. Warsaw downtown towers [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/voz-europa-blog.jpg)

▲ Warsaw downtown towers [Pixabay].

COMMENT / Anna K. Dulska

Often when we think of Central Europe the country that comes to mind is Germany. This association seems to be a very distant echo of the nineteenth-century term Mitteleuropa (literally " Middle Europe") that encompassed the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Second German Reich and was turned into an expansionist geopolitical conception by Germany during World War I. However, subsequent peace treaties reflected in the new political map a formal recognition of the great diversity that already existed in Central Europe. However, the subsequent peace treaties reflected in the new political map a formal recognition of the great diversity that had existed in the region since ancient times. The subjection of newly created or recreated states such as Poland, Hungary or Czechoslovakia to Soviet domination under the Yalta and Potsdam agreements did not put an end to this diversity and since the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 these countries have been searching for their place in today's world and Europe.

There is no clear definition of what Central Europe is today and to understand it in a simpler and more intuitive way, it could be said that for geopolitical, historical and cultural reasons it is neither strictly Western Europe nor Eastern Europe, but an intermediate area that for centuries has acted as a bridge between the two (one of those bridges that during the ups and downs of history sometimes get burned). Nor is there a consensus on the countries that make it up. According to the narrower definition, they are Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary, while according to the broader definition, in addition to these four, they are Austria, southeastern Germany, the Baltic countries (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia), Slovenia, western Ukraine and northern Italy. Some also add Switzerland, Liechtenstein and the rest of Germany, but thus their delimitation seems to be too diluted and confused.

The current history of the region tips the balance in favor of the narrow view. The trajectories of Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary since 1945, on the one hand, and their transitions to democracy after 1989, on the other, mean that within the geographic region and despite some considerable differences among them, these four countries constitute a distinct political, socioeconomic and cultural bloc. In the early 1990s this sort of imagined community was transformed into an intergovernmental organization known as the Visegrad group (the name of a Hungarian castle where in the 14th century the kings of Poland, Hungary and Bohemia had met and where in 1991 the founding agreement was signed), sometimes abbreviated to V4. Among its objectives were close economic cooperation (agreement Central European Free Trade Agreement, CEFTA), integration with the European Union (completed in 2004, after which all four left CEFTA) and integration with NATO (formalized in 1999; in 2004 in the case of Slovakia). Once these goals were achieved, the initiative lost momentum and seemed to become obsolete.

However, over the past three years, a shift in this aspect can be observed due to the phenomena that are challenging the European Union from outside and from within: migration from the Middle East, growing international tensions and terrorism. It is undeniable that all three are to a greater or lesser extent interrelated and for Europeans, whether Western, Central or Eastern, have a common denominator: security. While the lack of a deliberate and consensual strategy at the level of the European institutions to deal with this issue was evident until very recently challenge, the Central European states, especially Poland and Hungary, want to or have been forced to take matters, at least those that directly affect them, into their own hands. During the course of recent history their neighbors and partners did not have many occasions to hear them speak with their own voice and now it seems to be causing them some consternation.

A good example of this is the concern raised in Brussels and Berlin by the policies carried out by the Polish Government, both in relation to the domestic and international status . Paradoxically, these policies seem to be proving beneficial both for the State and for its society (which, after the halfway point of the term of office, still mostly supports the Government). However, the measures being taken to curb Warsaw's "authoritarian drift", as some media are describing it, especially the interference of EU high officials in the country's internal legislation, over which they have no competence, hinder the dialogue between the Polish Government and the Union's institutions. The threat of activating article 7 of the Treaty on European Union on the suspension of voting rights in the case of non-compliance with the demands of Brussels makes it impossible to rule out that such tensions could provoke other (after Brexit) irreparable fractures within the EU.

In the current geopolitical status , the voices about the need for a profound discussion on the future of the European Union are getting louder and louder, and Central Europe may once again have to play the role of a bridge. For the time being, as far as migration policy is concerned, it seems that the EU has proved V4 right. With the river in turmoil, the question arises as to whether the EU can afford an unnecessary and damaging internal weakening at a time when it needs unity the most.

Miloš Zeman and Andrej Babiš share the limelight in a political system not designed for two personalities

The Czech Republic has a president (Miloš Zeman), reelected in January for a second term, whose party has no presence in Parliament, and a prime minister (Andrej Babiš) who was out of position between January and May due to lack of sufficient support among legislators. Zeman and Babiš have backed each other and share criticisms of Brussels - for example, they reject the European Union's refugee quotas - but their strong personalism and fickle positions are causing friction.

![Andrej Babiš (left) and Miloš Zeman (right) during the inauguration of the former as prime minister, January 2018 [Czech Gov.] Andrej Babiš (left) and Miloš Zeman (right) during the inauguration of the former as prime minister, January 2018 [Czech Gov.]](/documents/10174/16849987/chequia-elecciones-blog.jpg)

▲ Andrej Babiš (left) and Miloš Zeman (right) during the inauguration of the former as prime minister, January 2018 [Czech Gov.]

article / Jokin de Carlos Sola

The political climate in the Czech Republic has not sedimented after the last electoral cycle. The legislative elections of October 20 and 21, 2017, called after a government crisis, saw a breakdown of the traditional parties and the arrival of many new faces in Parliament, giving rise to a political fractioning that has taken its toll.

Amid a hung Parliament, Andrej Babiš, leader of the best-performing party, ANO 2011, moved in December to form a minority Executive, becoming the first head of government in the history of the Czech Republic to come from neither the Civic Democrats nor the Social Democrats. In January, however, Babiš had to resign after losing a question of confidence; in May he succeeded in forming a new government, this time in coalition with the Social Democrats and, for the first time since the fall of the Iron Curtain, with the support of the Communists.

Against this backdrop of political disputes, presidential elections took place on January 12 and 13, 2018. The second round was contested by outgoing President Miloš Zeman, who was reelected, and Jirí Drahoš, in a contest that polarized the electorate between traditional economic protectionism and a critical stance towards the European Union (Zeman) and more open positions towards NATO and the EU (Drahoš).

In the end, Babiš and Zeman - former participants in the Velvet Revolution that put an end to the communist regime, after which both have had several ideological ups and downs, becoming controversial figures - have to share an institutional and political protagonism that is certainly complex. The Czech Republic has a parliamentary system, in which the president of the country is directly elected by the citizens and has the power to appoint and dismiss the prime minister, as well as to dissolve the bicameral parliament.

Legislative elections

In the 2017 Czech parliamentary elections, the ANO 2011 party won, whose name includes the year it was created and the acronym for Action of Dissatisfied Citizens, which together give rise in Czech to the word Yes. The election marked a parliamentary collapse of many of the old parties, including the Social Democrats of the ČSSD (from being the ruling party it dropped to sixth place), the Communists of the KSČM (they came in fifth place), the Christian Democrats of the KDU-ČSL (they were seventh) and the Liberals of TOP 09 (they finished eighth). The only old party to survive with relative strength were the conservatives of Civic Democracy (ODS), who finished second. Several new parties, on the other hand, gained relevance: this was the case, in addition to ANO itself, of the Pirate Party and the conservative and strongly nationalist Liberty and Direct Democracy (SPD), led by Tomio Okamura.

Andrej Babiš is called the Czech Donald Trump, not so much because of his ideology, but because of his flamboyant personality and his great fortune (he is the second richest man in the country). His statement of core values has been very fickle. Of communist origin, he founded his own political party in 2011, which he christened ANO 2011. It is a party with generally centrist views and a certain syncretism. It is also described as "populist" for its changes of speech, especially in relation to the European Union: before the general elections the party held Eurosceptic positions, to then develop a rather pro-EU policy from the Government.

Babiš was deputy prime minister and finance minister in the previous government led by Buhoslav Sobotka's Social Democrats. He is the owner of group media MFRA, which publishes two of the country's leading newspapers, Lidové noviny and Mladá fronta DNES, and operates the Óčko television company.

He is a controversial figure, not only because of some of his political stances, such as the rejection of the immigrant quotas established by the EU, but also because of several past scandals. He was accused of having collaborated with the secret police of the communist regime, of having fraudulently used EU subsidies and of participating in bribes for the sale of the state company Unipetrol, whose privatization was managed by Miloš Zeman, someone close to Babiš himself, when he was prime minister.

|

Apportionment of seats in the Chamber leave of the Czech Parliament [Wilkipedia]. |

Presidential elections

The presidential election was held in January 2018. It was the second time that the president was elected by direct universal suffrage. Miloš Zeman, who was seeking reelection, and Jiri Drahoš, president of the Academy of Sciences, went to the second round. There were those who compared this electoral battle with the one between Macron and Le Pen in France, but the ideological comparison is not complete. Drahoš described himself as pro-European and pro-NATO, and advocated that the Czech Republic should assume a greater role in the European Union, but he was critical of the EU's policy of welcoming immigrants, both Muslim and African, and rejected refugee quotas.

In the end, Zeman won with 52% support, while Drahoš got 48%, a somewhat tighter result than in the previous presidential election. ANO 2011's support in the runoff was decisive for Zeman's victory. The districts of Prague, Brno and other liberal areas with larger urban populations voted for Drahoš, while the countryside and border areas voted for Zeman.

Miloš Zeman was a member of the Communist Party until 1970 and switched to the Social Democratic Party in 1992, whose leadership he held between 1993 and 2001, years in which he served as Czech prime minister. He left that party in 2007 and two years later created his own, baptized as the Civil Rights Party: an electoral platform for his presidential candidacies, which does not have deputies or senators. In this personalist training , traditional right-wing and left-wing positions are mixed. On the one hand, the party believes in a mixed Economics , with a preference for public services and a high state expense , in a protectionist conception of the Economics. On the other hand, it promotes a cultural conservatism that avoids multiculturalism and the arrival of immigrants. This has made the party very popular in rural areas close to the borders.

Zeman became president of the Czech Republic in 2013. Zeman's first presidential term was highly controversial inside and outside the country. With him in Prague Castle came the entrance in the European Union, but he has subsequently been one of the main opponents of EU quotas for immigrants and has supported both Poland and Russia in their disputes with the authorities in Brussels. Zeman's closeness to Putin sets him apart from most leaders of the Visegrad countries, who take an anti-Russian stance.

Two leaderships

From the presidency, Miloš Zeman has maintained the lines already marked in his first term. If in European affairs his rejection of refugee quotas has put him at odds with the EU leadership, his closeness to Israel, Russia and China in international politics has also result annoyed Brussels.

Zeman was the only European leader to support Trump when he decided to move the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, recognizing the latter city as the capital of Israel. This was not a surprise, as Zeman has always shown his support for the Jewish state: on April 25 he celebrated Israel's Independence Day at his residency program . However, the Czech Republic has not moved its embassy to Jerusalem since the decision must be made by the government, and the government has not agreed to do so. On other Middle East issues, Zeman has given support to Russia, condemning the actions of the United States and its allies in Syria.

Zeman has also aligned himself with Beijing, opening the country to important Chinese investments, such as that of the energy company CEFC, whose headquarters in Shanghai were visited in March by several of his advisors. The opening to foreign investment has caused some concern in Brussels about the lack of control mechanisms to monitor the takeover of strategic sectors. In the framework of his promised "economic diplomacy" Zeman has defended China's project New Silk Road.

If Zeman and Babiš started from good relations, the last few months have led to several frictions. In the last weeks of his first term, Zeman put Babiš in charge of forming a government after his party became the most voted party in a very divided Parliament. Having just assumed the position as prime minister, Babiš offered Zeman the support of his ANO 2011 in the second round of the presidential election. Zeman has then made efforts to consolidate Babiš' position in Parliament. However, the latter's difficulties in having a stable majority have led to disagreements between the president and the prime minister over which parties should build the government majority. The open anti-Europeanism or anti-NATO stance of some of the potential partners made it difficult for Babiš, who in May formed the government again after having had to resign in January for lack of parliamentary support.

Events have shown that both Zeman and Babiš have strong personalities and that both seem determined to assert their political position, which may generate tension in the Czech Republic's institutional development . At the same time, both have shown an ease in changing speech according to what they think is the majority sentiment of Czechs, which has contributed to giving them a populist profile .

The days of the Velvet Revolution, when Zeman and Babiš shared a foxhole, are too far away, but it is worth remembering the words of Vaclav Havel, the main leader of that revolt and later president of the country: "Ideology is a deceptive way of relating to the world. It offers human beings the illusion of identity, dignity and morality, while at the same time making it easier for them to detach themselves from these principles".

ESSAY / Elena López-Dóriga

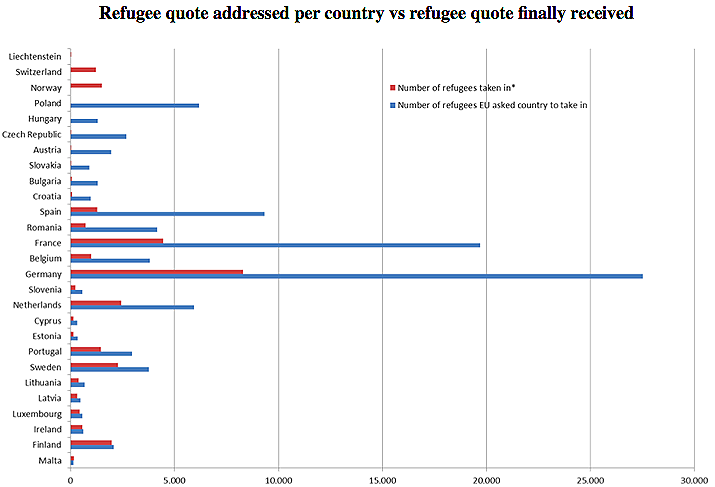

The European Union's aim is to promote democracy, unity, integration and cooperation between its members. However, in the last years it is not only dealing with economic crises in many countries, but also with a humanitarian one, due to the exponential number of migrants who run away from war or poverty situations.

When referring to the humanitarian crises the EU had to go through (and still has to) it is about the refugee migration coming mainly from Syria. Since 2011, the civil war in Syria killed more than 470,000 people, mostly civilians. Millions of people were displaced, and nearly five million Syrians fled, creating the biggest refugee crisis since the World War II. When the European Union leaders accorded in assembly to establish quotas to distribute the refugees that had arrived in Europe, many responses were manifested in respect. On the one hand, some Central and Eastern countries rejected the proposal, putting in evidence the philosophy of agreement and cooperation of the EU claiming the quotas were not fair. Dissatisfaction was also felt in Western Europe too with the United Kingdom's shock Brexit vote from the EU and Austria's near election of a far right-wing leader attributed in part to the convulsions that the migrant crisis stirred. On the other hand, several countries promised they were going to accept a certain number of refugees and turned out taking even less than half of what they promised. In this note it is going to be exposed the issue that occurred and the current situation, due to what happened threatened many aspects that revive tensions in the European Union nowadays.

The response of the EU leaders to the crisis

The greatest burden of receiving Syria's refugees fell on Syria's neighbors: Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. In 2015 the number of refugees raised up and their destination changed to Europe. The refugee camps in the neighbor countries were full, the conditions were not good at all and the conflict was not coming to an end as the refugees expected. Therefore, refugees decided to emigrate to countries such as Germany, Austria or Norway looking for a better life. It was not until refugees appeared in the streets of Europe that European leaders realised that they could no longer ignore the problem. Furthermore, flows of migrants and asylum seekers were used by terrorist organisations such as ISIS to infiltrate terrorists to European countries. Facing this humanitarian crisis, European Union ministers approved a plan on September 2015 to share the burden of relocating up to 120,000 people from the so called "Frontline States" of Greece, Italy and Hungary to elsewhere within the EU. The plan assigned each member state quotas: a number of people to receive based on its economic strength, population and unemployment. Nevertheless, the quotas were rejected by a group of Central European countries also known as the Visegrad Group, that share many interests and try to reach common agreements.

Why the Visegrad Group rejected the quotas

The Visegrad Group (also known as the Visegrad Four or simply V4) reflects the efforts of the countries of the Central European region to work together in many fields of common interest within the all-European integration. The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia have shared cultural background, intellectual values and common roots in diverse religious traditions, which they wish to preserve and strengthen. After the disintegration of the Eastern Block, all the V4 countries aspired to become members of the European Union. They perceived their integration in the EU as another step forward in the process of overcoming artificial dividing lines in Europe through mutual support. Although they negotiated their accession separately, they all reached this aim in 2004 (1st May) when they became members of the EU.

The tensions between the Visegrad Group and the EU started in 2015, when the EU approved the quotas of relocation of the refugees only after the dissenting votes of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia were overruled. In asking the court to annul the deal, Hungary and Slovakia argued at the Court of Justice that there were procedural mistakes, and that quotas were not a suitable response to the crisis. Besides, the politic leaders said the problem was not their making, and the policy exposed them to a risk of Islamist terrorism that represented a threat to their homogenous societies. Their case was supported by Polish right-wing government of the party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice) which came to power in 2015 and claimed that the quotes were not comprehensive.

Regarding Poland's rejection to the quotas, it should be taken into account that is a country of 38 million people and already home to an exponential number of Ukrainian immigrants. Most of them decided to emigrate after military conflict erupted in eastern Ukraine in 2014, when the currency value of the Ukrainian hryvnia plummeted and prices rose. This could be a reason why after having received all these immigration from Ukraine, the Polish government believed that they were not ready to take any more refugees, and in that case from a different culture. They also claimed that the relocation methods would only attract more waves of immigration to Europe.

The Slovak and Hungarian representatives at the EU court stressed that they found the Council of the EU's decision rather political, as it was not achieved unanimously, but only by a qualified majority. The Slovak delegation labelled this decision "inadequate and inefficient". Both the Slovak and Hungarian delegations pointed to the fact that the target the EU followed by asserting national quotas failed to address the core of the refugee crisis and could have been achieved in a different way, for example by better protecting the EU's external border or with a more efficient return policy in case of migrants who fail to meet the criteria for being granted asylum.

The Czech prime minister at that time, Bohuslav Sobotka, claimed the commission was "blindly insisting on pushing ahead with dysfunctional quotas which decreased citizens' trust in EU abilities and pushed back working and conceptual solutions to the migration crisis".

Moreover, there are other reasons that run deeper about why 'new Europe' (these recently integrated countries in the EU) resisted the quotas which should be taken into consideration. On the one hand, their just recovered sovereignty makes them especially resistant to delegating power. On the other, their years behind the iron curtain left them outside the cultural shifts taking place elsewhere in Europe, and with a legacy of social conservatism. Furthermore, one can observe a rise in skeptical attitudes towards immigration, as public opinion polls have shown.

|

* As of September 2017. Own work based on this article |

The temporary solution: The Turkey Deal

The accomplishment of the quotas was to be expired in 2017, but because of those countries that rejected the quotas and the slow process of introducing the refugees in those countries that had accepted them, the EU reached a new and polemic solution, known as the Turkey Deal.

Turkey is a country that has had the aspiration of becoming a European Union member since many years, mainly to improve their democracy and to have better connections and relations with Western Europe. The EU needed a quick solution to the refugee crisis to limit the mass influx of irregular migrants entering in, so knowing that Turkey is Syria's neighbor country (where most refugees came from) and somehow could take even more refugees, the EU and Turkey made a deal on the 18th of March 2016. Following the signing of the EU-Turkey deal: those arriving in the Greek Islands would be returned to Turkey, and for each Syrian sent back from Greece to Turkey one Syrian could be sent from a Turkish camp to the EU. In exchange, the EU paid 3 billion euros to Turkey for the maintenance of the refugees, eased the EU visa restrictions for Turkish citizens and paid great lip-service to the idea of Turkey becoming a member state.

The Turkey Deal is another issue that should be analysed separately, since it has not been defended by many organisations which have labelled the deal as shameless. Instead, the current relationship between both sides, the EU and V4 is going to be analysed, as well as possible new solutions.

Current relationship between the UE and V4

In terms of actual relations, on the one hand critics of the Central European countries' stance over refugees claim that they are willing to accept the economic benefits of the EU, including access to the single market, but have shown a disregard for the humanitarian and political responsibilities. On the other hand, the Visegrad Four complains that Western European countries treat them like second-class members, meddling in domestic issues by Brussels and attempting to impose EU-wide solutions against their will, as typified by migrant quotas. One Visegrad minister told the Financial Times, "We don't like it when the policy is defined elsewhere and then we are told to implement it." From their point of view, Europe has lost its global role and has become a regional player. Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban said "the EU is unable to protect its own citizens, to protect its external borders and to keep the community together, as Britain has just left".

Mr Avramopolus, who is Greece's European commissioner, claimed that if no action was taken by them, the Commission would not hesitate to make use of its powers under the treaties and to open infringement procedures.

At this time, no official sanctions have been imposed to these countries yet. Despite of the threats from the EU for not taking them, Mariusz Blaszczak, Poland's former Interior minister, claimed that accepting migrants would have certainly been worse for the country for security reasons than facing EU action. Moreover, the new Poland's Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki proposes to implement programs of aid addressed to Lebanese and Jordanian entities on site, in view of the fact that Lebanon and Jordan had admitted a huge number of Syrian refugees, and to undertake further initiatives aimed at helping the refugees affected by war hostilities.

To sum up, facing this refugee crisis a fracture in the European Union between Western and Eastern members has shown up. Since the European Union has been expanding its boarders from west to east integrating new countries as member states, it should also take into account that this new member countries have had a different past (in the case of the Eastern countries, they were under the iron curtain) and nowadays, despite of the wish to collaborate all together, the different ideologies and the different priorities of each country make it difficult when it comes to reach an agreement. Therefore, while old Europe expects new Europe to accept its responsibilities, along with the financial and security benefits of the EU, this is going to take time. As a matter of fact, it is understandable that the EU Commission wants to sanction the countries that rejected the quotas, but the majority of the countries that did accept to relocate the refugees in the end have not even accepted half of what they promised, and apparently they find themselves under no threats of sanction. Moreover, the latest news coming from Austria since December 2017 claim that the country has bluntly told the EU that it does not want to accept any more refugees, arguing that it has already taken in enough. Therefore, it joins the Visegrad Four countries to refuse the entrance of more refugees.

In conclusion, the future of Europe and a solution to this problem is not known yet, but what is clear is that there is a breach between the Western and Central-Eastern countries of the EU, so an efficient and fair solution which is implemented in common agreement will expect a long time to come yet.

Bibliography:

J. Juncker (2015). A call for Collective Courage. 2018, from European Commission Website.

EC (2018). Asylum statistics. 2018, from European Commission Website.

International Visegrad Fund (2006). Official Statements and communiqués. 2018, from Visegrad Group Website.

Jacopo Barigazzi (2017). Brussels takes on Visegrad Group over refugees. 2018, from POLITICO Website.

Zuzana Stevulova (2017). "Visegrad Four and refugees. 2018, from Confrontations Europe (European Think Tank) Website.

Nicole Gnesotto (2015). Refugees are an internal manifestation of an unresolved external crisis. 2018, from Confrontations Europe (European Think Tank) Website.

The EU has backed down on the project, but Germany still gives support to the Russian initiative

The project of a second set of gas pipelines through the Baltic Sea, in order to transport Russian gas to the European Union without crossing Ukraine, has divided the EU governments. Some Eastern and Central European countries, backed by the United States, argue against any dependency on Russian gas supplies, but Germany keeps its support to the Russian plans.

![The routes of the Nord Stream and the planned Nord Stream 2 pipelines from Russia to Germany [Gazprom]. The routes of the Nord Stream and the planned Nord Stream 2 pipelines from Russia to Germany [Gazprom].](/documents/10174/16849987/nordstream-blog.jpg)

▲The routes of the Nord Stream and the planned Nord Stream 2 pipelines from Russia to Germany [Gazprom].

ARTICLE / Ane Gil Elorri

The natural gas consumption for nowadays is essential to have basic necessities covered. Therefore, it's imperative for everyday life. Nevertheless, it goes through a laborious process before it reaches the consumers. The gas needs to be extracted from the land or sea subsurface, and transported, before it reaches its destiny, being pipelines the most common via of transportation.

The EU's domestic gas production has been declining and the reserves in the North Sea depleted. Therefore, in order to meet demands, the EU has turned to other suppliers; being the most important Russia, Saudi Arabia and Norway. In fact, a lot of countries in the European Union are heavily dependent on Russian imports, especially of natural gas, which often go through transit countries such as Ukraine and Belarus. The decisions are all make through the EU-Russia Energy Dialogue. Russia has the largest gas reserves in the world. With 44,600 billion cubic meters, Russia has 23.9 percent of the world's currently known gas reserves, followed by Iran (15.8 percent), Qatar (13.5 percent), the United States, and Turkmenistan (4.3 percent each).

The most prominent European energy supply is the Nord Stream Pipelines. Nord Stream are a twin set of pipelines that provide gas transportation capacity for the natural gas, which comes from the Western Russia (Vyborg) into Lubmin, Germany, for the distribution into the European gas grid. This system is composed by a set of 1,224-kilometre pipelines through the Baltic Sea, and each hold the capacity to transport 27.5 billion cubic metres of natural gas a year. Line 1 became operational in November 2011 and by October 8, 2012 the system was fully operational, having taken the construction of these pipelines 30 months.

The desire of a grand-scale gas transport between Russia and the western Europe goes back to the 1970's, to the contract between a German company (Ruhrgas AG) and Gazprom (national Russian gas company) to supply natural gas. In 2000 the European Commission recognized the need for a pipeline in the Baltic Sea. In December 2005, the North European Gas Pipeline Company was established and by October 4, 2006, the North European Gas Pipeline was officially renamed Nord Stream. It was finally completed and functional in October 2012.

The Nord Stream project was very ambitious. Nevertheless, it was completed on time, on budget, and without permanently impacting the environment. The Nord Stream Pipeline system is fully operational and capable of transporting up to 55 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas every year to Europe.

Now, a new project is developing based on the success of the Nord Stream Pipelines: Nord Stream 2. This project will benefit from the experience of the previous pipeline, which has set a new high for the environmental, technical and safety standards throughout its planning, construction and operation. The idea is to add a new set of twin pipelines along the Baltic Sea route to increase the capacity of gas transportation in order to meet the demands of Europe. In fact, this new pipeline will create a direct link between Gazprom and the European consumers.

The Nord Stream 2 project is implemented by the Nord Stream 2 AG project company, where Gazprom is the sole shareholder. In October 2012, the shareholders of the Nord stream project examined the possibility of constructing a third and fourth pipeline and came to the conclusion that it was economically and technically attainable. In April 2017, Nord Stream 2 AG signed the financing agreements for the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project with ENGIE, OMV, Royal Dutch Shell, Uniper, and Wintershall. These five European energy companies will provide long-term financing for 50 per cent of the total cost of the project.

The entry point into the Baltic Sea of the twin pipeline will be the Ust-Luga area of the Leningrad Region. Then the pipeline will stretch across the Baltic Sea. Its exit point in Germany will be in the Greifswald area close to the exit point of the original Nord Stream. The route covers over 1,200 kilometres.

The total capacity of the second twin set of pipelines is 55 billion cubic metres of gas per year. Therefore, the sum with the prior pipelines would give an outstanding number of 110 billion cubic metres of gas per year. Nord Stream 2 will be operational before late 2019.

This project is defended with the argument that it supposed a diversification of the routs transporting natural gas to Europe and to elevate the energetic security due to the instability of the transit of gas through Ukraine. For now, a lot of the natural gas consumed by Europe comes from Russia through Ukraine. Nevertheless, if this project goes through, Ukraine will lose 2,000 million dollars for the transit of natural gas, and even the proportion of gas will decrease (which is also for staff use) leading to the collapse and finalization of the transit of natural gas through Ukraine. Furthermore, if Hungary, Slovakia and Poland receive natural gas through the Nord Stream 2 pipelines instead of through Ukraine, it will be very difficult that Ukraine receives gas from the west, seeing as Gazprom along with others controls EUGAL (European Gas Pipeline Link) can reduce the supply of gas to those companies that provide gas to Ukraine.

The cost of 1,000 cubic meters in 100 kilometres through Nord Stream 2 would cost 2.1 million dollars while through Ukraine it costs 2.5 million dollars. The tariff of transportation of natural gas through Nord Stream is 20% lower than through Ukraine.

|

The main Russian gas pipelines to Eastern and Central Europe [Samuel Bailey/CC]. |

Only half of the European Union members approve the negotiations between the EU and Russia over the Nord Stream 2 Project. It is true that the natural gas demand of Europe is growing each year but some countries such as the Baltics are against anything that has to do with Russia. Besides the US, thanks to fracking, has become the biggest producer of gas, and is now looking to substitute Russia as the main gas supplier of the EU.

But other countries are in favour of this project. In January 31 this year, Germany gave its permission to begin the construction of the pipelines of Nord Stream 2 in their territorial waters. Berlin also authorized the construction of the section of 55 kilometres that will go through the terrestrial part situated in Lubmin. In April this year, Finland has also given the two permissions needed to begin the construction.

Nevertheless, Gazprom will be facing a few difficulties in order to pull through with this project. The company still needs that other countries, such as Norway, Denmark and Russia, give authorizations and permissions to construct the pipelines in their exclusive economic zone. There is a risk that Denmark doesn't authorize these new pipelines. The Danish Agency of Energy and the Foreign Office both have to give their approval but can deny the permit if Nord Stream 2 represents a danger for the environment. Another problem is purely political: the European Commission is trying to make the implementation of the project fit with the EU legislation. In November 2017, the European Commission prepared a list of amendments to its energy legislation, known as the Third Energy Package, which will pursue gas pipelines that come from the markets of countries that have the Brussels standards. Because of this, Gazprom won't be able to be the only shareholder of the Nord Stream 2 project and the pipelines will have to carry gas of other companies that have nothing to do with Gazprom.

Although, as previously mentioned, Nord Stream 2 has already received the two permits necessary in Germany and Finland in order to begin the construction, it seems that not many European countries are in favour of this project. In fact, since this April, the EU and the European Commission have withdrawn their support claiming that Nord Stream 2 does not encourage the diversification of gas supply, and they give more significance to the gas pipelines going through the Ukrainian territory in context of diversification of supply routes.

Other EU countries and of the region, such as Ukraine, Denmark, the Baltic States and Poland, have continuously spoken against Nord Stream 2, claiming that the project will increase Europe's dependence on imported Russian gas. Nevertheless, German Chancellor Angela Merkel supports this project, considering it to be an economic project which does not pose a threat to EU energy security, has is expected, seeing as the Nord Stream 2 is a joint venture between Russia's Gazprom, France's Engie, Austria's OMV AG, the Anglo-Dutch company Royal Dutch Shell, and Uniper and Wintershall, both German.

Nevertheless, the most vocally active countries against this project are the US and Ukraine. On one side, the United States believes that this project would undermine Europe's overall energy security and stability. It would also provide Russia other ways to pressure European countries, especially Ukraine. The US even threatened the EU firms to be subjected to Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA). On the other side, Ukraine's efforts to prevent the implementation of Nord Stream appears to be futile. They openly stated that this would conclude on the Russian monopoly on the world gas market, which would lead in Europe to an energy crisis and to an economic and political destabilization, and called for the international community to step in. Unfortunately, Germany is as headstrong as ever, stating that underwater pipeline to bring gas from Russia could not go forward without Ukrainian involvement in overland transit.

As the recent expulsion of European diplomats in Moscow shows, the global political relations have worsened considerably in the last few years. In fact, some would say that it the worst condition since the Cold War. This new political situation has had consequences on the Nord Stream 2, causing European countries to oppose to this project. The ultimate defender left standing of the programme is Germany, even the EU has backed down after Ukraine's protest. Ukraine has every right to oppose to this project, seeing as Russia has had nothing more but cold moves towards this country(cut off gas supplies in the middle of winter, Crimea), and is not outrageous to think that this project would ultimately affect the country, especially economically. Therefore, this project does not diversify the sources of natural gas, the first Nord Stream already reached this objective. The second Nord Stream, however, would grant Russia a monopoly of natural gas, which is not recommendable seeing as it would create Europe's dependence on Russia, and Russia could take advantage of it. Unfortunately, Russia will not give up this project, even with mostly everybody turns against it.

REPORT / Jokin de Carlos Sola

Simplicity is the best word to describe this Baltic country. Its flag represents the main landscape of the country; a white land covered in snow, a black forest, and a blue light sky. And so is its economy, politics and taxation. What a minimalistic artwork is Estonia.

Estonia is the smallest of the three Baltic countries, with the smallest population and a quite big border with Russia, concretely 294 km long. Even so, Estonia has a bigger GDP per capita (17,727.5 USD in 2016 according to World Bank) than the other two Baltic states: Latvia and Lithuania. It has a bigger presence in the markets and a bigger quality of life according to the OECD in a study done it in 2017.

Technology is a very important part of Estonia's economy. According to the World Bank, 15% of Estonia's GDP are high tech industries. Following the example of Finland, Estonia has made technology the most important aspect of their economy and society. But not just that, with the eyes faced towards the future, or as the Estonians call it "Tulevik", this former part of the Soviet Union of 1,3 million inhabitants has become the most modernized state in Europe.

The 24th of February of 2018 Estonia celebrated the 100th anniversary of the its independence, so it is interesting to see how the evolution of this small country is and will continue to be.

All this has been possible because of different figures like Laar, Ilves, Ansip, and Kotka.

download the complete report [pdf. 3,4MB] [pdf. 3,4MB

download the complete report [pdf. 3,4MB] [pdf. 3,4MB

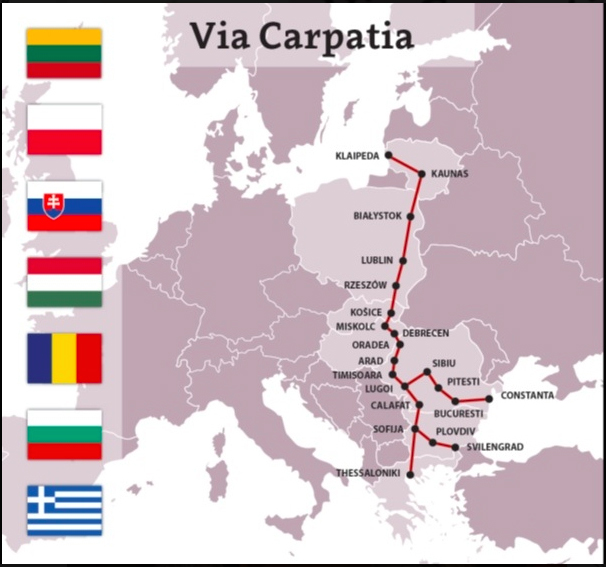

A new north-south motorway on the eastern edge of the EU aims to be the entrance gateway to Europe for goods from China.

Seven European countries have joined forces for the project Via Carpatia, a motorway that will run from Lithuania to Romania and Greece, increasing the interconnectedness of the EU's eastern region. Its promoters envisage the infrastructure as part of the new Silk Road, as a gateway to Europe for goods arriving from China and the rest of Asia.

▲Polish motorway section to be part of the project Via Carpatia [Generalna Dyrekcja Dróg Krajowych i Autostrad Oddział w Rzeszowie].

article / Paula Ulibarrena

Via Carpatia is a European route; it is actually an ambitious project interstate motorway linking the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea. The route will start in Lithuania, in the city of Kaunas, then continue through Poland, following the Bialystok-Lublin-Rzeszów route; it will then enter Slovakia to cover the Presov-Kosz section, and in Hungary it will run through Miskolc-Debrecen.

On the territory of Romania, the route will be divided into two directions, one towards the port of Constanta on the Oradea-Arad-Timisoara-Lugoj-Deva-Sibiu-Pitesti-Bucarest-Constanta route and the other penetrating into Bulgaria via the future bridge over the Danube at Calafat-Vidin and with the possibility of extending the project to Greece, in the Mediterranean, at the southern border of the European Union.

The project Via Carpatia was C in 2006, when the transport ministers of Poland, Lithuania, Slovakia and Hungary signed a joint declaration to extend the network trans-European transport network by creating a route to connect these four states along a north-south axis. In 2010, project was joined by Romania, Bulgaria and Greece to extend the new route through their respective territories.

Andrzej Adamczyk, Poland's Minister of Public Works, said in May 2017 that the entire 600-kilometre route of this infrastructure in Poland will be completed by 2025. According to him, Via Carpathia "will allow the full potential of the provinces it passes through to be developed, providing a boost for the poorer regions of eastern Poland and the economies of the area".

The purpose of project is to promote the economic development of the region, providing facilities for the development of small and medium-sized business and the creation of technology parks, which should contribute to the creation of employment and enhance research and innovation.

This initiative currently reinforces other policies that also have the goal development of infrastructures in Eastern Europe, such as the 3 Seas Initiative. But it also opens the door to other more ambitious projects, such as the 16+1 and the new Silk Road, both launched by the People's Republic of China.

Connection with China

The 16+1 mechanism is a Chinese initiative aimed at intensifying and expanding cooperation with 11 EU Member States from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and 5 Balkan countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia) in subject investment, transport, finance, science, Education and culture. In the framework of the initiative, China has identified three possible priority areas for economic cooperation: infrastructure, high technologies and green technologies.

The Riga Declaration, a document issued in November 2017 at the China-ECO summit, sets the roadmap for such cooperation. In the Latvian capital, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and the leaders of Central and Eastern European countries agreed to enhance cooperation internship and increase people-to-people exchanges. In particular, the leaders reaffirmed their desire to achieve effective connectivity between ports on the Adriatic, the Baltic and the Black Sea, through roads and the use of inland waterways.

"The Adriatic-Baltic-Black Sea port cooperation will be a new engine for China-ECO cooperation," said Liu Zoukiu, researcher of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, adding that the combination of Chinese equipment, European technology and ECO markets will be a great model for cooperation between China and these 16 nations.

Trade between China and Central and Eastern European countries reached $56.2 billion in 2015, up 28 per cent from 2010. Chinese investment in these 16 nations exceeded $5 billion, while in the opposite direction investment was $1.2 billion.

issue The data also shows that the number of goods train lines between China and Europe has increased to 39 since the connections began in 2011. 16 Chinese cities regularly operate these convoys to a dozen European cities. Beijing's interest in the CEE countries lies precisely in the fact that they are Europe's gateway to the new Silk Road.

|

The future north-south connection, Baltic-Black/Mediterranean [viacarpatia.eu]. |

The European Gateway to the New Silk Road

The 21st Century Silk Road, which the Chinese government has dubbed One Belt One Road (OBOR), is not an institution with clearly defined rules, but rather a strategic vision: it alludes to the ancient Silk Road, the commercial and cultural link between East and West for more than two millennia. The new route aims to be a connectivity network consisting of maritime and land-based economic corridors linking China and the rest of Asia with the Middle East, Europe and Africa. In this way, OBOR puts continents, oceans, regions, countries, cities, international and regional organisations on contact .

The new diplomatic language appears as a seductive tool of Chinese soft power, exported through the routes of trade and diplomacy that reach the gates of Europe. Evoking the historical framework of harmonious coexistence and mutual cultural enrichment, Chinese officialdom defines the "Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence" as OBOR's core values: (1) mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity; (2) agreement mutual non-aggression; (3) agreement mutual non-intervention in internal affairs; (4) equality and mutual benefit; (5) peaceful coexistence.

China seeks to diversify its trade routes and partners, opening up new consumer markets. At the same time, it is securing supplies of energy and raw materials. Finally, it is expanding its logistical structure and building a China-centred trade network .

Beijing set up a state investment fund, the Silk Road Fund, in 2014 with a capital of $40 billion, earmarked for One Belt, One Road investments. China insists that such financial institutions are not intended to replace existing ones, but rather to complement and collaborate with them in a spirit of inclusiveness and mutual benefit. However, voices from the United States and the European Union have raised some concerns.

US and EU suspicions

US analysts speak of the Chinese European Century (and warn that as investment and trade with Europe grows, so will Beijing's influence over European policies. Indeed, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) already has funds of $100 billion, or 50 per cent of the World Bank's capital.

The 16+1 platform was launched to the chagrin of the EU, which was not consulted on the matter beforehand. Brussels observes a status of dependency on the part of some of the continent's poorest countries, caused by a trade asymmetry in favour of China: trains arrive in Warsaw with tons of Chinese goods, but return half-empty. The creation of infrastructure and new production and distribution centres for Chinese goods sometimes progresses beyond the EU's control. Consequently, EU legislative compliance and even European unity itself may be affected.

For the most part, the national interests of European countries seem to be dominated by the pure logic of Economics and lack strategic vision. They have so far made a common and coordinated EU policy towards OBOR impossible. In the absence of unity, Europe is throwing stones at itself and ironically applying to itself the effective "divide and rule" strategy described by the Chinese philosopher Sunzi 2,500 years ago.

New international order

The international order is changing: OBOR, which in paternalistic embrace now encompasses almost all European countries, presents itself as the Chinese alternative to the West's model that has dominated the world until now.

The US is being replaced as the world's leading Economics and losing its political hegemony to the rise of China. This is demonstrated by the reactions of Washington's staunchest allies in Europe, London and Berlin, in joining the OBOR initiative without much hesitation and despite US warnings.

China proposes to create a new international economic and financial order together with Europe. The most notorious milestone of this close partnership is China's injection of up to €10 billion into the EFSI, a decision agreed between Beijing and Brussels in April 2016, making China the largest investor in the so-called Juncker Plan. Together, they can generate economic growth and the creation of employment by building and modernising infrastructure networks that improve intra-European connectivity. This can facilitate the opening up of European products and services for export to new markets and improve their conditions for entrance to China's own market. Europe can benefit from improved connectivity with other hitherto remote regions.

▲Viktor Orban, at a rally near the Romanian border in May 2017 [Károly Árvai/Hungarian government].

ANALYSIS / Elena López-Doriga

On April 8, 2018, parliamentary elections were held in Hungary for the renewal of the 199 members of the National Assembly, the only chamber of the Hungarian Parliament. The high turnout of 68.13% exceeded that of the 2010 elections, when 64.36% of the electoral roll turned out to vote, a record high not seen since 2002. Prime Minister Viktor Orban, in power since 2010, secured a fourth term, the third in a row, as his party, Fidesz, and its ally, the Christian Democratic People's Party, won 134 of the 199 seats. Orban, the longest-serving European leader as head of government after Angela Merkel, has in some respects become as influential a leader as the German chancellor.

These electoral data -the high turnout and the broad support achieved by a leader not well regarded by all in Brussels- raise some questions. Why has there been so much social mobilization at the time of voting? Why is the result of these elections in the spotlight of the European Union?

Historical background

Hungary is a country located in Central Europe bordering Austria, Croatia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Ukraine. The second largest river in Europe, the Danube, crosses the entire country and divides the capital of Budapest into two different territories (Buda and Pest).

Hungary joined the European Union in 2004. This event was longed for by Hungarians as they saw it as an advance in their democracy, a step forward for the country's development and a rapprochement with the admired West. It was the desire to make a change of course in their history, since, after the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, the country lived under two totalitarian regimes since World War II: first under the rule of the Arrow Cross Party (fascist, pro-German and anti-Semitic), during which 80,000 people were deported to Auschwitz, and later by the occupation of the Soviet Union and its post-war policies. In those times individual freedoms and freedom of speech ceased to exist, arbitrary imprisonment became commonplace, and the Hungarian secret police carried out series of purges both within and outside the Party hierarchies. Thus, Hungarian society suffered great repression from the beginning of World War II in 1945, which did not stop until the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989.

In economic terms, the transition from communism to capitalism was very hard for vast social sectors. From a centralized Economics with highly protected sectors and heavy agricultural subsidies, a particularly severe adjustment plan was adopted by the government elected in March 1990 in the first free elections.

Accession to the European Union symbolized a turning point in Hungary's history, in a process of incorporation to the West that was previously marked by entrance in NATO in 1999. Becoming part of the EU was the step towards the democracy that Hungary desired, and this broad social consensus was evidenced by the majority support that the accession obtained - 83% of the votes - in the referendum of 2003.

Hungary in the European Union

Becoming a new EU member had a positive impact on Hungary's Economics , leading to an obvious development and providing competitive advantages for foreign companies establishing a permanent presence in the country. But despite these appreciable advances and the enthusiasm shown by Hungary upon accession to the EU, the picture has changed a lot since then, so that Euroskepticism has spread markedly among Hungarians. In recent years, a strong disagreement with the Brussels policies adopted during the 2015 refugee crisis has emerged in the domestic public opinion.

That year, Brussels decided to relocate the 120,000 refugees who had arrived in Hungary (from Syria, who were moving along the Balkan route to Germany and Austria) and Italy (mostly from North Africa). To distribute the refugees, quotas were established, setting the issue number of refugees that each country should take in based on its size and GDP. The quota policy was challenged by the group Visegrad countries (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia) and Romania. Hungary erected a fence several hundred kilometers long on its southern border and refused to accept the reception quotas.

This attitude of closing borders and refusing to take in refugees was criticized by the leaders of the Union, who went so far as to threaten these countries with sanctions. The difficulty of a consensus led to the signing in 2016 of a agreement with Turkey so that this country would retain the flow of Syrian refugees. In 2017 the quotas for the distribution through the EU of the refugees who had previously arrived expired, without fill in thus the relocation initially raised. Although the moment of greatest political confrontation on this issue in the EU has passed, the refugee crisis has created a great divergence between the two targeted blocs, eroding the supposedly common European project .

In light of this status, Hungary's parliamentary elections on April 8, 2018 were particularly important, as the citizens of that country were going to have the opportunity to pronounce themselves on the ongoing pulse between Budapest and Brussels.

The main candidates

Going into the election, the front-runner was the coalition of the conservative Fidesz party and the Christian Democratic People's Party, with 54-year-old Viktor Orbán as candidate. Orbán first came to prominence in 1989 when, at the age of 26, he defied the communist regime and began to champion liberal principles, making him a symbol of Hungarians' aspirations to break free from totalitarianism and embrace Western values. However, his return to power in 2010, after a first term in office between 1998 and 2002, was marked by a shift towards a conservative tendency, characterized by greater control over the Economics, the media and the judiciary. Orban claims to be an advocate of an "illiberal democracy": a system in which, although the Constitution may formally limit the powers of the Government, in internship certain freedoms such as freedom of speech or thought are restricted. Orban often puts to test the red lines of the EU by presenting himself as a defender of a "Christian Europe" and detractor of irregular immigration.

The party that intended to pose the main electoral challenge to Fidesz, taking away a good part of its voters, was surprisingly one located even further to the right: Jobbik (Movement for a Better Hungary), founded in 2003 and considered one of the most powerful extreme right-wing political organizations in the European Union. For years, this party did not hide its xenophobic, anti-Roma, anti-Semitic, nationalist and radically opposed to the prevailing political system in the EU, betting on a Hungary outside it. However, from 2013 onwards he moderated his language. While Orban was adopting an increasingly radical line, the leader of Jobbik, Gábor Vona, was tempering the positions of his party to present it as a conservative option, alternative to Fidesz, capable of attracting votes from the center. Gyöngyösi, one of the party's nationalist leaders, said: "We are the party of the 21st century, while Fidesz is from the last century and represents the old. The division between left and right no longer makes sense, it is part of the past, of the old politics".

On the other side of the political spectrum, a list formed by the Socialist Party(MSZP) and the center-left environmentalist party Parbeszed ("Dialogue"), headed by a leader of the latter, Gargely Karacsony, was running in the elections. The left-wing candidate had broad support from the MSZP, but not from his former colleagues in the environmentalist LMP party, from which he split five years ago, which could lead to a split vote.

|

Completed a second fence at the border with Serbia, in April 2017 [Gergely Botár/Hungarian government]. |

The election campaign

During the campaign there was speculation about a possible loss of votes for Fidesz due to a series of corruption scandals involving government officials accused of embezzling European aid money. Jobbik and other groups of civil service examination took advantage of this status to promote themselves as anti-corruption parties, focusing a good part of their campaign on this issue and advocating for an improvement of public services, especially healthcare.

However, the most prominent topic of the election campaign was not corruption, the malfunctioning of the public health system or low wages, but immigration. The Orbán government had refused to accept the refugee quotas imposed by the EU from Brussels, arguing that taking in migrants is a matter of domestic policy in which foreign organizations should not intervene. He insisted that Hungary has the right to refuse to receive immigrants, especially if they are Muslims, reiterating his rejection of multiculturalism, which he considers a mere illusion. Orbán was of the opinion that the refugees arriving at Hungary's gates were not fighting for their lives, but were economic migrants in search of a better life. Therefore, Orbán's political campaign was a clear message: Illegal immigrants in Hungary: yes or no? Who should decide about Hungary's future, the Hungarians or Brussels?

Reducing the electoral call to one question had the main effect of a broad social mobilization. According to civil service examination, Orbán used the topic of migration to draw popular attention away from widespread corruption.

Another point core topic in Fidesz's political campaign was the constant accusations against George Soros, whom Orbán identified as the main enemy of the State. Soros is an American billionaire, of Jewish-Hungarian origin, who through his Open Society Foundation (OSF) finances various NGOs dedicated to promote liberal, progressive and multicultural values in different parts of the world. In 1989 Soros funded Viktor Orban to study in England, and in 2010 he donated $1 million to his government to help with environmental cleanup after a chemical accident. But Soros' reputation in Hungary took a hit during the 2015 migration crisis. His advocacy of human attention to refugees ran up against Orban's attitude. During the campaign, the latter accused Soros of using OSF to "flood" Europe with a million migrants a year and undermine the continent's "Christian culture."

In addition, prior to the elections, Fidesz passed an amendment to the Hungarian higher Education law, which sets new conditions for foreign universities in Hungary, something that has been seen as a direct attack on the Central European University of Budapest. The Soros-funded institution is highly regarded for promoting critical thinking, liberal values and academic freedom. The new legislation threatens university autonomy, the free hiring of professors and the international character of degrees.

The European Commission showed its differences with the Orbán government on several of the issues that occupied the electoral campaign. Thus, it expressed its dissatisfaction with the new university law, considering that it is not compatible with the fundamental freedoms of the EU internal market, as it "would violate the freedom to provide services and the freedom of establishment". He also criticized that Orbán had not complied with the refugee quota, despite the ruling of the Court of Justice, and that he had campaigned using the disagreement he has with the EU for electoral purposes.

The result of the elections

In the April 8, 2018 elections, the Fidesz party (in its alliance with the Christian Democratic People's Party) won a third consecutive wide victory, even bigger than the previous one, with almost half of the popular vote (48.89%) and its third two-thirds absolute majority (134 out of 199 seats). It was the first time since the fall of communism in 1989 that a party had won three elections in a row.

The Jobbik party managed to become the leading party on civil service examination, coming in second place with 19.33% of the vote and 25 seats. However, its vote growth was minimal and it gained only two extra seats, remaining virtually stagnant at the 2014 figures. Jobbik's second place was rather propitiated by the weakness of the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), whose debacle pushed it into third place, with 12.25% of the vote and 20 seats. It was the first time since 1990 that the MSZP did not come in first or second place, putting an end to the bipartisanship it had maintained with Fidesz since 1998.

On the other hand, since its return to government in 2010, Fidesz has significantly modified the electoral system, reducing the issue number of legislators from 386 to 199 and eliminating the second round, which does not favor the smaller parties, which could form alliances between rounds of voting. By securing two thirds of the chamber, Fidesz will be able to continue governing comfortably and reforming the Constitution to suit itself.

EU reaction

A week after the elections, tens of thousands of opponents took to the streets of Budapest, disagreeing with an electoral system described as "unfair", which has given Prime Minister Viktor Orban a landslide victory at the polls after a campaign based on a refusal to accept refugees.

The congratulatory letter that the president of the European committee , Donald Tusk, addressed to Orban was considered by various media to be cooler than the one issued on other similar occasions. The EU is concerned that Orban continues with his defense of an "illiberal" democracy and that he seems to be leading the country towards authoritarian tendencies. The government's purchase of many media outlets in recent years, in order to isolate civil service examination and make more propaganda, resembles what has happened in countries such as Russia and Turkey.

It is true that with Orban at the head of the government Hungary has grown economically at a good pace and that the middle classes have improved their status, but his latest victory has been due not only to the good economic management , but the defense of values that the Hungarian people consider important (essentialism, Christianity, respect for borders).

European socialists have not been pleased with Orban's new victory, insinuating that it is a setback for democracy in Hungary. The joy that the populist parties have expressed over his victory is test that Orban, whose training Fidesz still belongs to the European People's Party, has become an exponent of modern ultra-nationalism, which threatens democratic ideas of the European Union.

For the time being, Brussels is being cautious with Hungary, even more so than with the British Brexit, since Viktor Orban, seen by many as "the EU rebel", unlike the UK, wants to remain within the bloc, but change part of the ideals he represents.

Bulgaria's semester focuses on refugee crisis and Western Balkans

Bulgaria's presidency of the European Union, in addition to advancing in the concretization of the 'Brexit', puts on the table particularly sensitive issues for Central and Eastern Europe, such as the migratory routes that enter Europe through the southeast of the continent and the advisability of the future integration of the states born of the former Yugoslavia, of which so far only Croatia has joined the EU.

▲European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker and Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borissov [Nikolay Doychinov-Bulgarian Presidency].

article / Paula Ulibarrena García

During this first semester of 2018, for the first time, Bulgaria holds the rotating presidency of the committee of the European Union (EU). The Bulgarian presidency has as its main challenges the management of the migration crisis and the 'Brexit' negotiations. As a special goal has been marked to put the focus on the Western Balkans. During the semester, Bulgaria hopes to take the final steps towards the euro and to join the Schengen area.

Under the slogan "Unity is strength", Bulgaria - the poorest country in the EU - has set itself an ambitious diary until June. The Bulgarian government, formed by the conservative populist GERB party and the ultra-nationalist Patriotic Front, has set out to help make the European bloc stronger, more stable and more united.

To this end, Sofia wants to foster consensus, cohesion and competitiveness, with the specific challenge of overcoming existing differences in the handling of the refugee crisis. Given the rejection by several partners of quotas for the relocation of asylum seekers, Bulgaria will seek "a sustainable system for managing immigration," with "common rules that are enforced," the Bulgarian presidency program highlights.

Migration crisis

Dialogue with third countries to facilitate the return of migrants without the right to asylum and the strengthening of external border control are some of the measures planned by the executive led by the Bulgarian Prime Minister, the conservative populist Boiko Borisov.

Bulgaria's position on the Syrian refugee crisis is that the adoption of a mechanism to relocate refugees is only a solution provisional. The government in Sofia believes that a lasting and solid solution must be found under which to limit the pressure on the external borders of the EU and the secondary migration resulting from it. It proposes that the EU should work as a matter of priority and urgency together with its EU partners with a view to stabilizing the countries of origin and helping the transit countries. Bulgaria, which has Turkey as a neighbor, considers Turkey to be core topic for the resolution of the problem and proposes that the EU should forge urgent measures to strengthen Turkey's capacity to receive refugees. Bulgaria has always been keen for the agreements to provide for Turkey to admit the refugees that the EU can refund from Greece.

For Sofia, it is necessary to clarify the distinction between economic migrants and refugees and to move towards "solidarity mechanisms" that are acceptable to all member states, recalling in this regard the failure of the mandatory quota system for the relocation of refugees in Italy and Greece.

Western Balkans

Another priority of the Bulgarian presidency is to place the countries of the Western Balkans in the sights of an EU, which for the time being is not considering any further enlargement. Some countries in the region, such as Serbia and Montenegro, are actively negotiating their entrance, which they hope will take place within the next five years. Meanwhile, Bosnia Herzegovina, Albania, Macedonia and Kosovo are still waiting to formally start negotiations.

Among the nearly 300 meetings planned during the Bulgarian EU presidency, a special summit on May 17-18 between EU leaders and these six aspirants stands out.

"The European project will not be complete without the integration of the Balkans", warned the Minister manager of the Bulgarian Presidency, Lilyana Pavlova. Bulgaria insists on the convenience of helping a European region still marked by the political instability of the new and small states that emerged after the Yugoslav war.

After Croatia's integration into the European Union on July 1, 2013, it is logical that other countries of the former Yugoslavia intend to follow. Montenegro (which even has a bilateral agreement with Bulgaria of technical-political attendance on topic) and Albania are already official candidates, and there will probably soon be an invitation for Serbia and Macedonia.

The Economics, stability of institutions and democratic transparency have always been and will always be decisive factors in the integration process. For this reason, today, the question of the development of the Balkans and the region of southeastern Europe is very present in the European diary since the big donors of the European budgets do not forget the problems caused by the integration of countries such as Poland, Hungary, Romania or Bulgaria itself. In fact, four countries in the area are subject to the economic policy of the Union: Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia.