Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Security and defence .

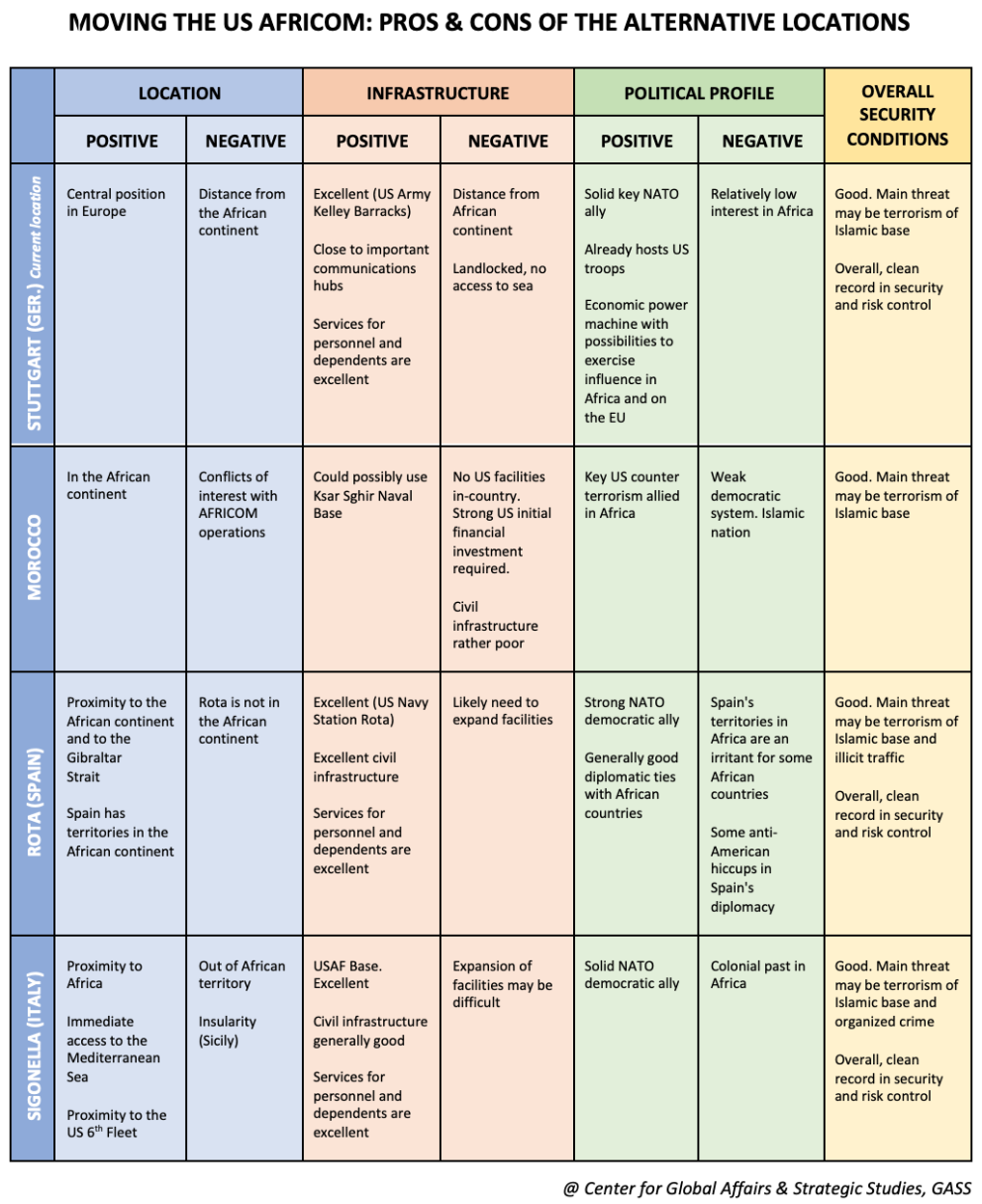

As the United States considers moving its AFRICOM from Germany, the relocation to US Navy Station Rota in Spain offers some opportunities and benefits

The United States is considering moving its Africa Command (USAFRICOM) to a place closer to Africa and the US base in Rota, Spain, in one of the main alternatives. This change in location would undoubtedly benefit Spain, but especially the United States, we argue. Over the past years, there has been a 'migration' of US troops from Europe, particularly stationed in Germany, to their home country or other parts of the hemisphere. In this trend, it has been considered to move AFRICOM from "Kelly Barracks," in Stuttgart, Germany, to Rota, located in the province of Cádiz, near the Gibraltar Strait.

![Entrance to the premises of the US Navy Station Rota [US DoD]. Entrance to the premises of the US Navy Station Rota [US DoD].](/documents/16800098/0/rota-blog.jpg/3d6dc4ec-a235-79a3-e478-4706f1f129e7?t=1621877332236&imagePreview=1)

Entrance to the premises of the US Navy Station Rota [US DoD].

ARTICLE / José Antonio Latorre

The US Africa Command is the military organisation committed to further its country's interests in the African continent. Its main goal is to disrupt and neutralize transnational threats, protect US personnel and facilities, prevent and mitigate conflict, and build defense capability and capacity in order to promote regional stability and prosperity, according to the US Department of Defense. The command currently participates in operations, exercises and security cooperation efforts in 53 African countries, committing around 7,200 active personnel in the continent. Its core mission is to assist African countries to strengthen defense capabilities that address security threats and reduce threats to US interests, as the command declares. In summary, USAFRICOM "is focused on building partner capacity and develops and conducts its activities to enhance safety, security and stability in Africa. Our strategy entails an effective and efficient application of our allocated resources, and collaboration with other U.S. Government agencies, African partners, international organizations and others in addressing the most pressing security challenges in an important region of the world". The headquarters are stationed in Stuttgart, Germany, more than 1,500 kilometers away from Africa. The United States has considered to move the command multiple times for logistical and strategic reasons, and it might be the time the government takes the decision.

Bilateral relations between Spain and the United States

When it comes to the possible relocation of AFRICOM, the main competitor is Italy, with its military base in Sigonella. An ally that has been increasingly important to the United States is Morocco, which has offered to accommodate more military facilities as its transatlantic ally continues to provide the North African country with weapons and armament. However, it is important to remember that the United States and Spain cooperate in NATO, fortifying their security and defense relations in the active participation in international missions. Although Italy also belongs to the same organizations, it is important to emphasize the strategic advantages of placing the command in Rota as opposed to in Sigonella: Rota it is a key point which controls the Strait of Gibraltar and contains much of the needed resources for the relocation. Spain combines the fact that it is a European Union and NATO member, while it has territories in Africa and shares key interests in the region due to multiple current and historical reasons. Spain acts as the bridge with Northern Africa in the West. This is an argument that neither Morocco nor Italy can offer.

The relations between Spain and the United States are regulated by the Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement and Agreement on Defense Cooperation (1988), following the Military Facilities in Spain: Agreement Between the United States and Spain Pact (1953), enacted to formalize the alliance in common objectives and where Spain permits the United States to use facilities in its territory. There are two US military instructions in Spanish territory: US Air Force Base Morón and US Naval Station Rota. Both locations are strategic as they are in the south, essential for their proximity to the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea and, particularly, to Africa. Although it is true that Morocco offers the same strategic advantages as Rota, it is important to take into account the similarities in culture, the Western point of view, the shared strategies in NATO, and the shared democratic and societal values that the Spanish alternative offers. The political stability that Spain can offer as part of the European Union and as a historical ally to the United States is not comparable with Morocco's.

If a relocation is indeed in the interest of the United States, then Spain is the ideal country for the placement of the command. Since the consideration is on the Naval Station in Rota, then the article will evidently focus on this location.

Rota as the ideal candidate

Rota Naval Station was constructed in 1953 to heal bilateral relations between both countries. It was placed in the most strategic position in Spain, and one of the most in Europe. Naval Station Rota is home to Commander, Naval Activities Spain (COMNAVACT), responsible for US Naval Activities in Spain and Portugal. It reports directly to Commander, Navy Region Europe, Africa and Southwest Asia located in Naples, Italy. There are around 3,000 US citizens in the station, a number expected to increase by approximately 2,000 military personnel and dependents due to the rotation of "Aegis" destroyers.

Currently, the station provides support for NATO and US ships as well as logistical and tactical aid to US Navy and US Air Force units. Rota is key for military operations in the European theatre, but obviously unique to interests in Africa. To emphasize the importance of the facility, the US Department of Defense states: "Naval Station (NAVSTA) Rota plays a crucial role in supporting our nation's objectives and defense, providing unmatched logistical support and strategic presence to all of our military services and allies. NAVSTA Rota supports Naval Forces Europe Africa Central (EURAFCENT), 6th Fleet and Combatant Command priorities by providing airfield and port facilities, security, force protection, logistical support, administrative support and emergency services to all U.S. and NATO forces". Clearly, Naval Station Rota is a US military base that will be maintained and probably expanded due to its position near Africa, an increasingly important geopolitical continent.

Spain's candidacy for accommodating USAFRICOM

Why would Spain be the ideal candidate in the scenario that the United States decides to change its USAFRICOM location? Geographically speaking, Spain actually possesses territories in Africa: Ceuta, Melilla, "Plazas de Soberanía," and Canary Islands. Legally, these territories are fully incorporated as autonomous cities and an autonomous community, respectively.

Secondly, the bilateral relations between Spain and the United States, from the perspective of security and defense, have been very fluid and dynamic, with benefits for both. After the 1953 convention between both Western countries, there have been joint operations co-chaired by the Secretary General of Policy of Defense (SEGENPOL) of the Spanish Ministry of Defense and the Under Secretary General for Defense Policy (USGDP) in the United States Department of Defense. Both offices plan and execute plans of cooperation that include: The Special Operations "Flint Lock" Exercise in Northern Africa, bilateral exercises with paratrooping units, officer exchanges for training missions, etc. It is important to add to this list that Spain and the United States share a special relationship when it comes to officers, because all three branches (Air Force, Army, Navy) have exchange programs in military academies or instructions.

Finally, when it comes to Spain, it must be noted that the fluid relationship maintained between both countries has created a very friendly and stable environment, particularly in the area of Defense. Spain is a country of the European Union, a long-time loyal ally to the United States in the fight against terrorism and in the shared goals of strengthening the transatlantic partnership. This impeccable alliance offers stability, mutual confidence and reciprocity in terms of Defense. The United States Africa Command needs a solid "host", committed to participating in active operations in Africa, and there is no better candidate than Spain. Its historical relationship with the countries in Northern Africa is important to take into account for perspective and information gathering. The Spanish Armed Forces is the most valued institution in society, and it is for sure more than capable of accommodating USAFRICOM to its needs in the South of the country, as it has always done for the United States, however, this remains a fully political decision.

The United States' position

Rota is an essential strategic point in Europe, and increasingly, in the world. The US base is well known for its support to missions from the US Navy and the US Air Force, and its responsibility only seems to increase. In 2009, the United States sent four destroyers from the Naval Base in Norfolk, Virginia, to Rota, as well as a large force of US Naval Construction units, known as "Seabees" and US Marines. It is also worth noting that NATO has its most important pillar of an antimissile shield in Rota, given the geographical ease and the adequate facilities. From the perspective of infrastructure, on-hand station services, security and stability, Rota is the ideal location of the USAFRICOM compared to Morocco.

Moreover, Rota is, and continues to be, a geographical pinnacle for flights from the United States heading to the Middle East, particularly Iraq and Afghanistan. Most recently, USS Hershel "Woody" Williams arrived in Rota and joined NATO allies in the Grand African Navy Exercise for Maritime Operations (NEMO) that took place in the Gulf of Guinea in the beginning of October of 2020. In terms of logistics, Rota is more than equipped to host a headquarters of the magnitude of USAFRICOM and it would be economically efficient to relocate the personnel and their families as the station counts with a US Naval Clinic, schools, a commissary, a Navy Exchange, and other services.

The United States has not made a formal proposition to transfer Africa Command to Rota, but if there is a change of location, it is one of the main candidates. As Spain's Minister of Foreign Affairs González Laya stated, the possible transfer of USAFRICOM to Rota is a decision that corresponds only to the United States, but Spain remains fully committed with its transatlantic ally. González Laya emphasized that "Spain has a great commitment to the United States in terms of security and defense, and it has been demonstrated for many years from Rota and Morón". The minister reminded that Spain maintains complicity and joint work in the fight against terrorism in the Sahel with an active participation in European and international operations in terms of training local armies to secure order. A perfect example of the commitment is Spain's presidency of the Sahel Alliance, working for a secure Sahel under the pillars of peace and development.

In 2007, when USAFRICOM was established, it could have been reasonable to install the headquarters in Germany, but now geographical proximity is key, and what better country for hosting the command than Spain, which has territories in the continent. The United States already has a fully equipped military base in Rota, and it can count on Spain to guarantee a smooth transition. Spain's active participation in missions, her alliance with the United States and her historic and political ties with Africa are essential reasons to heavily consider Rota as the future location of USAFRICOM. Spain has been, and will continue to be, a reliable ally in the war against terrorism and the fight for peace and security. Spain is a country that believes in democracy, freedom and justice, like the United States. It is a country that has sacrificed soldiers in the face of freedom and has stood shoulder to shoulder with its transatlantic friend in the most difficult of moments. As a Western country, both countries have been able to work together and achieve many common objectives, and this will only evolve. As the interests in Africa expand, it is undoubtedly important to choose the best military facility to accommodate the command's military infrastructure as well as its personnel and their families. The United States, in benefit of its strategic objectives, would be making a very effective decision if it decides to move the Africa Command to Rota, Spain.

The Sahara conflict becomes more complicated for Spain with the migration crisis in the Canaries

The reactivation of the war in the former colony leaves Madrid with little room for manoeuvre in the face of the wave of migrants arriving in the Canary Islands.

The reactivation of the war in the former colony leaves Madrid with little room for manoeuvre due to the wave of migrants arriving in the Canary Islands.

Spain has never had an easy role in the Western Sahara conflict. Its exit from the North African territory took place in a context of decolonisation haste on the part of a UN that then preferred to take its time in the process. Spain has been caught between defending the rights of the Saharawis and the desirability of not damaging the complicated neighbourhood with Morocco. Now that the Polisario Front has reopened the war, with the aim of getting something moving internationally on the conflict, Spain is hamstrung by crises over the arrival of migrants in the Canary Islands, an archipelago located across the dividing line between Morocco and Western Sahara. Here is summary of the latest developments in the Saharawi question.

article / Irene Rodríguez Caudet

The Polisario Front has declared war on Morocco after 29 years of peace. This organisation, created primarily to defend the independence of Western Sahara from Spain, represents an important part of the Sahrawi population seeking self-determination for its people.

The Alawite kingdom, for its part, claims sovereignty over the territories. It undertook measures that triggered the recent conflict at the Guerguerat border crossing, where demonstrators blocked the road linking Western Sahara to Morocco. The Moroccan military fired on the rally on 13 November and the Polisario Front declared a state of war.

Western Sahara is a territory in a state of decolonisation since 1960 under the auspices of the UN as part of the processes carried out during the second half of the 20th century to put an end to the European colonial empires. This process continued until 1975, the year of the Green March, when an army of 350,000 Moroccan civilians marched into the former colony to claim it as their own, alongside Mauritania. At that point, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Rio de Oro (Polisario Front) began a guerrilla war that would not find a ceasefire until 1991.

Despite Morocco's efforts to possess the former Spanish colony, the Saharawis have had their own proclaimed republic since 1976, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (also known by the acronym SADR), recognised by several states - 84 in total, although more than half of them have cancelled, frozen or suspended recognition due to violations of their international obligations - and presided over by Brahim Gali.

Since Spain left the territory, the UN has issued several resolutions calling for a referendum on self-determination that would mark the future of Western Sahara as an independent country or propose other alternatives.

In this conflict, the different parties involved are pursuing different strategies. Morocco, for its part, intends to prolong the conflict in order to consolidate its power in Sahrawi territory. It does not envisage independence for the former Spanish colony, but promotes plans for limited autonomy in a project of agreement framework known as the "third way" for what it considers to be its southern provinces. Moreover, it occupies these provinces militarily, through border crossings, six military instructions and with more than half of the Saharawi territory under its control.

Frustrated by the UN's immobile position, the Polisario Front has always counted on the threat of a return to armed conflict. SADR consists of only a few territories that are fully supervised by it - roughly a quarter of Western Sahara - and has gained less global recognition than the Polisario Front as an organisation, which the UN admits as the representative of the Saharawi people.

The lack of new and more imaginative proposals from the UN, coupled with the attitude of the parties involved, particularly the Moroccan side, have made progress towards a satisfactory solution to the conflict impossible. The lack of progress, however, is not only due to these reasons. The Sahrawi refugees in Tindouf, Algeria, must also be taken into account. This is the longest humanitarian crisis in history, dragging on for 45 years and affecting 173,600 refugees, many of whom have known no other life.

The violent strategy, which prevailed for more than fifteen years, was abandoned in 1991 in favour of a ceasefire and negotiation tactics that are not proving very fruitful. Despite attempts at peaceful settlements, in mid-November this year, the Polisario Front declared a state of war, ending a peace that had lasted almost 20 years.

Morocco claims the Saharawi territories as its own and goes so far as to include them unabashedly as part of Morocco on the Kingdom's most recent official maps, similar to those of the early 20th century, when the Maghreb country had control over the Sahara. For this reason, after Spanish colonisation and subsequent decolonisation, Morocco claims the former colony. According to its authorities, the so-called "Sahrawi provinces" have always been under Moroccan sovereignty.

The conflict not only pits Rabat against El Aaiún, but also involves parties that support one leader or the other. On the one hand, there are the Arab countries - Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait - that support Morocco, and on the other hand, a nation that, despite having a very express desire to exercise its own sovereignty and claim SADR's legitimacy, has little or no international support.

In 2021, MINURSO, the mission statement deployed by the UN to guarantee peace and the holding of the referendum on self-determination, will be 30 years old since it began its deployment; to date it has 240 observers, but has not seen its goal. The Saharawis argue that the UN's work has not been effective in any respect and that it has only allowed the Moroccan plundering of the Sahara's natural resources. Nor has there been any progress on the referendum on self-determination, and the lack of action has led to the lifting of the ceasefire by the Saharawi government. The Polisario Front has now chosen to take these measures as the lack of progress by the UN's mission statement becomes increasingly evident.

The country of Mohammed VI has sent troops to quell the demonstrations in the main Saharawi towns and on the roads connecting Morocco to Western Sahara. Meanwhile, its counterpart claims to have caused material and human losses in the Moroccan military instructions located in Saharawi territory. Morocco does not recognise any of these allegations, but defends itself with fire in the face of the Polisario Front's threat.

Meanwhile, Dakhla, the second most populated city in Western Sahara, is serving as a corridor for small boats and dinghies, which in recent days have been arriving in large numbers at the port of Arguineguín, in Gran Canaria. This fact is causing Morocco and Spain to be even more concerned about status in the Sahara and to have to face this problem jointly, something complicated due to the historical confrontations between the two countries over the Saharawi conflict. However, while some are passing through, others are returning to their homeland: the Polisario Front has appealed to all Saharawis living in the country and abroad to join the struggle.

The status of Western Sahara is pending further developments in the conflict and the decisions taken by Morocco. While there are international positions that continue to call for a referendum on self-determination, the status quo will end up influencing the UN to accept the Moroccan autonomy proposal proposal . The Spanish government has avoided pronouncing itself in favour of the plebiscite, although there is division between the PSOE and Podemos, training which urges the holding of the enquiry. Although the migration crisis in the Canaries is due to more complex dynamics, the suspicion that Morocco has allowed the arrival of more refugees at a decisive moment in the reopened Sahara conflict obliges Spain to adopt a cautious attitude.

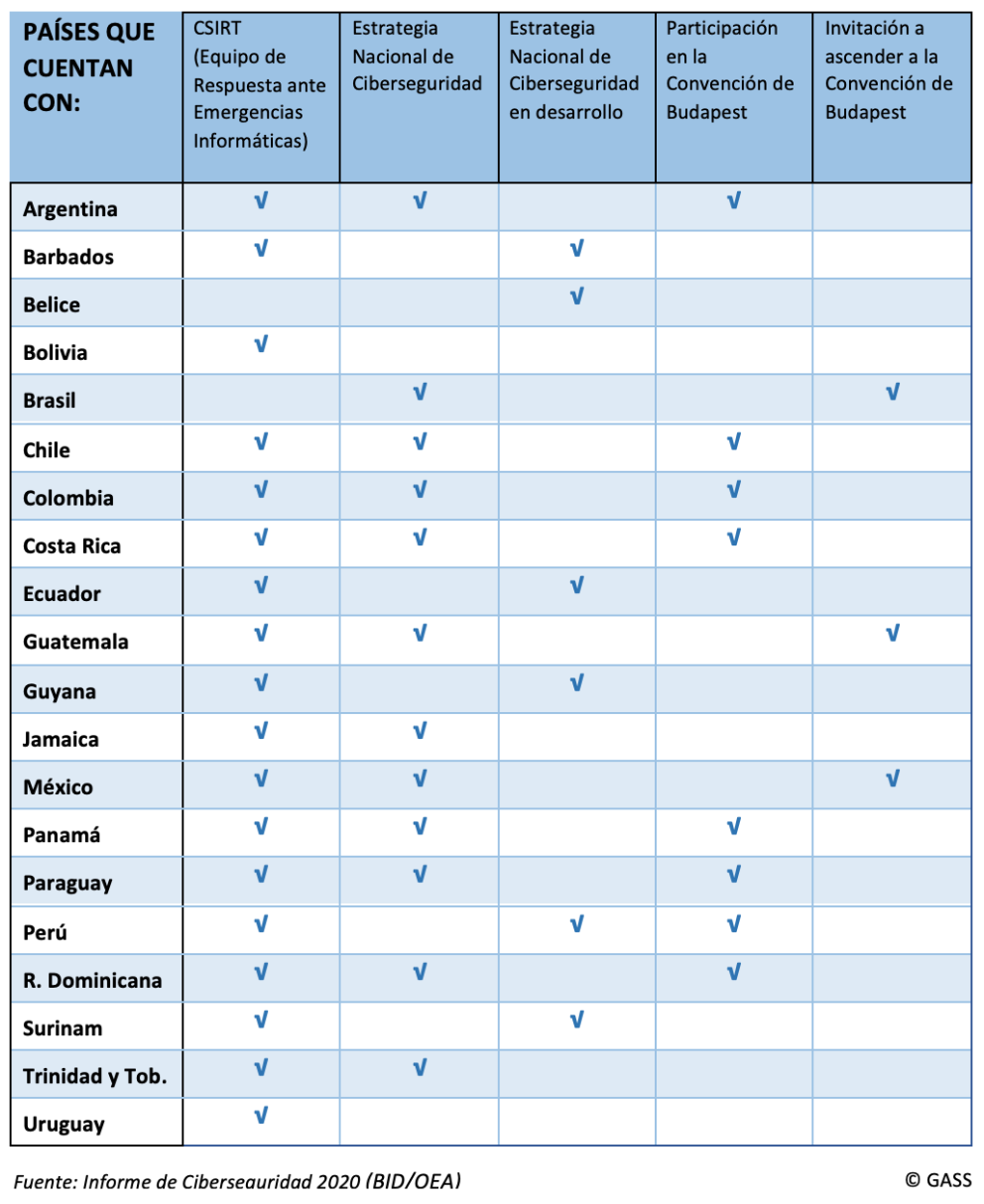

One third of countries have developed a national cybersecurity strategy, but mobilized capabilities are minimal

A dozen Latin American countries have already developed a national cybersecurity strategy, but overall the capacities mobilized in the region to deal with cybercrime and cyberattacks are so far limited. In a continent with a high use of social networks, but at the same time with some problems of network electricity and internet access that make it difficult to react to cyber-attacks, the risk of widespread organized crime groups increasingly resorting to cybernetics is high.

article / Paula Suárez

In recent years, globalization has made its way in all parts of the world, and with it have emerged several threats in the field of cyberspace, which requires special treatment by the governments of all states. Globally, and not only in Latin America, the main areas under threat in terms of cybersecurity are, essentially, computer crime, network intrusions and politically motivated operations.

The latest reports on cybersecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean, carried out jointly by the Inter-American Bank development (IDB) and the Organization of American States (OAS), indicate that one third of the countries in the region have begun to take some steps to address the growing cybersecurity risks. However, they also note that efforts are still limited, given the general lack of preparedness for the threat of cybercrime; they also point to the need for a reform of protection policies in the coming years, especially with the problems that have come to light with the Covid-19 crisis.

The IDB and the OAS (OAS) have collaborated on different occasions to publicize status and raise awareness of cybersecurity issues, which have been increasing as globalization has become part of everyday life and social networks and the internet become more deeply integrated into our day-to-day lives. To address this new reality, both institutions have created a Cybersecurity Observatory for the region, which has published several programs of study.

If until the 2016report cybersecurity was a topic little discussed in the region, currently with the increase of technology in Latin America and the Caribbean it has become a topic of interest for which states tend to be increasingly concerned, and therefore, to implement relevant measures, as highlighted in the 2020report .

Transportation, educational activities, financial transactions, many services such as food, water or energy supply and many other activities require cybersecurity policies to protect civil rights in the digital realm such as the right to privacy, often violated by the use of these systems as a weapon.

Not only socially, but also economically, investment in cybersecurity is essential to prevent the damage caused by online crime. For the Gross Domestic Product of many countries in the region, attacks on infrastructure can account for from 1% to 6% of GDP in the case of attacks on critical infrastructure, which translates into incompetence on the part of these countries to identify cyber dangers and to take the necessary measures to combat them.

According to the aforementioned study, 22 of the 32 countries analyzed are considered to have limited capabilities to investigate crimes, only 7 have a plan to protect their critical infrastructure, and 18 of them have established a so-called CERT or CSIRT (Computer Security Incident or Emergency Response Team). These systems are not currently developed uniformly in the region, and they lack the capacity and maturity to provide an adequate response to threats at network, but their implementation is necessary and, increasingly, they are supported by institutions such as the OAS for their improvement.

In this area, the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST) has a work core topic , because of the great need in this region, for attend to governments so that they can benefit from the identification of cyber threats and the strategic security mechanisms of the association, mainly to protect the economies of these countries.

As already mentioned, awareness of the need for such measures has been increasing as cyber attacks have also increased, and countries such as Colombia, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and Panama have established a proper strategy to combat this damage. In contrast, many other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean such as Dominica, Peru, Paraguay and Suriname have lagged behind in this development, and although they are on the way, they need institutional support to continue in this process.

The problem in combating such problems is generally rooted in the states' own laws. Only 8 of the 32 countries in the region are part of the Budapestagreement , which advocates international cooperation against cybercrime, and one third of these countries do not have appropriate legislation in their legal framework for cybercrime.

For the states party to agreement, these guidelines can serve as a great financial aid to develop domestic and procedural laws with respect to cybercrime, so it is promoting the adherence or at least the observation of them from organizations such as the OAS, with the recommendations of specialized units such as group of work on Cybercrime of the REMJA, which advises on the reform of criminal law with respect to cybercrime and electronic evidence.

On the other hand, it was not until the beginning of this year that, with the incorporation of Brazil, 12 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have established a national cybersecurity strategy, due to the lack of qualified human talent. Although it is worth mentioning the two countries in the region with the largest development in the field of cybersecurity, which are Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago.

Of the problems mentioned, we can say that the lack of national strategy in terms of cybersecurity exposes these countries to various attacks, but to this must be added that the companies that sell cybersecurity services and provide technical and financial support in the region are mostly from Israel or the United States, and are linked to a rather militarized security and defense perspective, which will be a challenge in the coming years because of the skill that China is showing on this side of the hemisphere, especially linked to 5G technology.

Cyber malpractices are a threat not only to the Economics of Latin America and the Caribbean, but also to the functioning of democracy in these states, an attack on the rights and freedoms of citizens and the values of society. For this reason, the need for investment in civilian infrastructure and military capacity is becoming apparent. To achieve this, the states of the region are willing to cooperate, firstly, in the unification of their legal frameworks based on the models of the Budapest agreement and the instructions of the European Union, whose perspective to face the new challenges in cyberspace is having a great impact and influence in the region.

In addition, with the upcoming Covid-19 crisis, the states of the region are generally willing to collaborate by developing their own national strategies, consistent with the values of the organizations they are part of, to protect both their current means and their emerging technologies (artificial intelligence, quantum, computing from high performing and others). Cyber threats are intended to be addressed from channels open to partnership and dialogue, since the Internet has no borders, and the harmonization of legal frameworks is the first step to strengthen not only regional but also international cooperation.

![Bahraini and UAE foreign ministers sign Abraham Accords with Israeli premier in September 2020 [White House]. Bahraini and UAE foreign ministers sign Abraham Accords with Israeli premier in September 2020 [White House].](/documents/16800098/0/acuerdos-blog.jpg/ad268976-c84e-2b4c-d2a5-ca36909e72e2?t=1621877040390&imagePreview=1)

Bahraini and UAE foreign ministers sign Abraham Accords with Israeli premier in September 2020 [White House].

essay / Lucas Martín Serrano

It is interesting to incorporate into any geopolitical analysis subject a touch of history. History is a fundamental financial aid for understanding the present. And most conflicts, problems, frictions or obstacles, whether between nations or public or private entities, always have an underlying historical background. Moreover, taken to the field of negotiation, regardless of the level of negotiation, demonstrating a certain historical knowledge of the adversary is useful because, on the one hand, it is not only a sample of interest and respect for him, which will always place us in an advantageous position, but, on the other hand, any stumbling block or difficulty that appears has ample possibilities of having its historical counterpart, and precisely there the path to a solution can be found. The party that has a greater depth of knowledge will significantly increase the chances of a solution that is more favourable to its interests.

In ancient times, the territory now occupied by the United Arab Emirates was inhabited by Arab tribes, nomadic farmers, craftsmen and traders. Plundering the merchant ships of European powers that sailed along its coasts, coming closer than was advisable, was commonplace. And, in a way, a way of life for some of its inhabitants. It was in the 7th century that Islam took root in the local culture. Of the two currents that emerged after the disputes that followed the death of the Prophet, it was the Sunni current that became dominant from the 11th century onwards.

In order to put an end to piracy and secure the maritime trade routes, the United Kingdom signed a peace treaty with the sheikhs in the area in 1820, signature . In 1853, a further step was taken and another agreement was signed, placing the entire territory under the military protectorate of the United Kingdom.

signature The area attracted the attention of powers such as Russia, France and Germany, and in 1892, to protect their interests, the agreement was set up, guaranteeing the British a monopoly on trade and exports.

The area encompassing today's seven United Arab Emirates plus Qatar and Bahrain became known as the "Trucial States".

During World War I, the Gulf's airfields and ports played an important role in the conflict in favour of the UK, development . At the end of World War II in 1945, the League of Arab States (Arab League) was created, made up of those with some colonial independence. The organisation attracted the attention of the Truce states.

In 1960, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was created, with Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait and Venezuela as founding members and headquartered in Vienna, Austria. The seven emirates, which would later form the United Arab Emirates, joined the organisation in 1967.

Since 1968, nine emirates on the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula had begun negotiations to form a federal state. Following the withdrawal of British troops final and after Bahrain and Qatar dissociated themselves from the process and gained independence separately, in 1971, six emirates became independent from the British Empire: Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm al Qaywayn and Fujairah, forming the federation of the United Arab Emirates, with a legal system based on the 1971 constitution. Once consolidated, they joined the Arab League on 12 June. The seventh emirate, Ras Al-Khaimah, joined the following year, with the strongest components being the emirates of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, the capital.

It was the beginning of the exploitation of the huge oil wells discovered years earlier that turned the tide at status. After the 1973 oil crisis, the Emirates began to accumulate enormous wealth, as OPEC members decided not to export any more oil to the countries that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War.

Oil and tourism based on urban growth and technological development are the main sources of prosperity in the country today, and a very important fact from all points of view is that 80-85% of the UAE's population is currently immigrant.

status current

It has been especially during the last decade, and partly as a consequence of events in the region since what became known as the Arab Spring, that the US has emerged as a regional power with the capacity to influence the region.

The main characteristic that can be attributed to this emergence on the international scene is the transformation of a conservative foreign policy, very much geared towards "self-preservation", towards a more open-minded one with a clear vocation not only to play a relevant role in the region, but also to influence it in order to protect its interests.

What can be seen as Abu Dhabi's main ambition is to become a major player capable of influencing the definition and establishment of governance Structures throughout the region according to its own model, securing and expanding trade routes, bringing in its neighbours to create a sufficiently powerful economic node with the capacity to forge closer ties with the entire East African region and Southeast Asia, in what seems another clear example of how the global geopolitical centre is already shifting definitively towards the Asia-Pacific axis.

The Emirati model has been able to evolve to integrate increasing economic openness with a conservative and strong-government model political whose main speech is built on the foundation of a well-entrenched and secure state. And all of this is coupled with a strong capacity as a service provider provider. Interestingly, the social model is relatively secular and liberal based by regional standards.

But a fundamental fact that cannot be forgotten is the outright rejection of any political or religious ideology that poses the slightest threat to the hegemony and supremacy of the state and its leaders.

It is Abu Dhabi, as the largest and most prosperous of the seven emirates, that exerts the most influence in setting the broad lines of both domestic and foreign policy. Indeed, the evolution of the UAE's established model is firmly associated with Abu Dhabi's crown prince and de facto leader of the emirate, Mohamed bin Zayed (MbZ).

What cannot be lost sight of is that, although MbZ and his inner circle of trust share the same vision of the world and politics, their actions and decisions do not necessarily follow a pre-established plan. There is no basic doctrine with set tactical and strategic objectives and the lines of work to follow in order to achieve them.

Their way of carrying out country strategy, if it can be called that, is based on a small group belonging to that inner circle, which puts on the table a number of usually tactical and reactive options to any problems or issues that arise to carry out. Based on these, the top leadership follows an ad hoc decision-making process that can lead to an excessive need for subsequent corrections and adjustments that in turn lead to missed opportunities.

Threats - status security

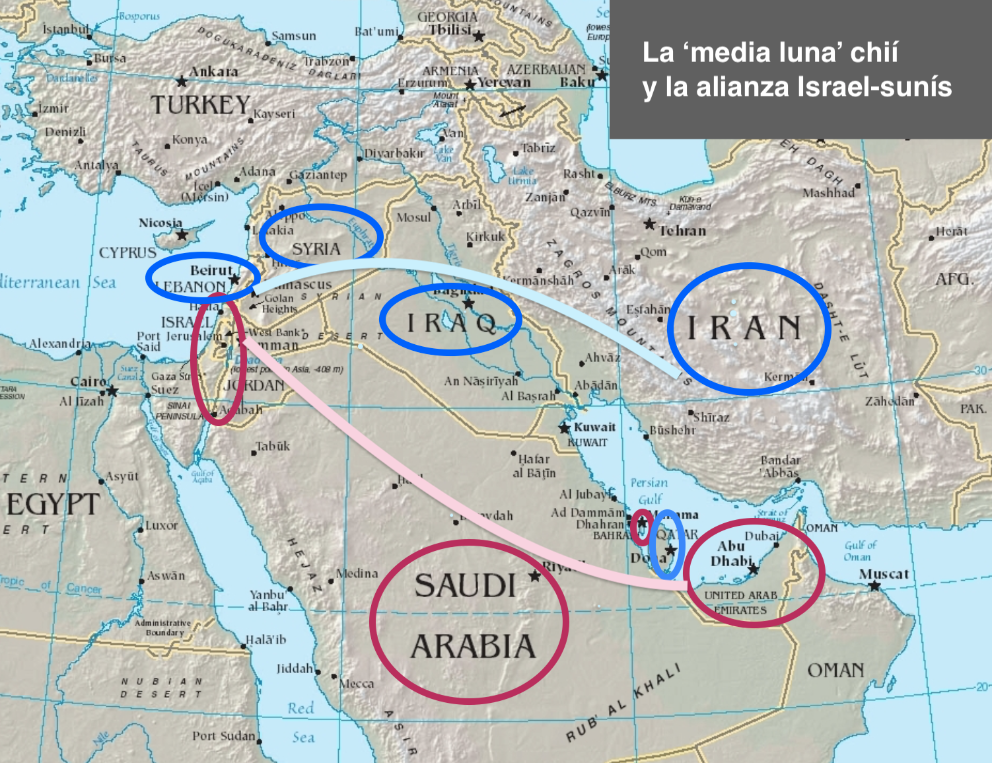

Emirati authorities have a clear perception of the main geostrategic threats to their development: on the one hand, the Iranian-promoted transnational spread of Islamist political ideology and, on the other, the influence sought by the Muslim Brotherhood and its promoters and supporters, including Qatar and Turkey, is perceived as an existential threat to their vision of a more secular form of government, as well as to the stability of the current regional status quo, given that it can act as a catalyst for radicalism in the area.

However, Abu Dhabi has been much more belligerent in its speech against the Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters, while remaining cautious in its stance against Iran.

The recent agreement with the State of Israel has served to undermine the credibility of many long-held clichés and has also highlighted the emergence of a Sunni-Jewish bloc as civil service examination to the belligerent and growing Shiite current led by Iran and its proxies, active in virtually every country in the region and in all regional conflicts.

This new status should serve to confirm to Western powers that in the Middle East region the view of their own problems has changed and Iran and its particular way of conducting foreign policy and defending its interests are now seen as a far more destabilising factor than the long-running Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The threat posed by Iran has acted as a catalyst in bringing together views, while Israel is nonetheless seen as providing stability both militarily and economically.

The UAE-Israel Treaty

On 15 September, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain formalised the normalisation of their relations. This agreement means that four Arab states have now accepted Israel's right to exist, and this is undoubtedly a real diplomatic success.

The fact that it was precisely the UAE and Bahrain is no coincidence. Neither state has engaged in a direct war against Israel. And, if this characteristic is common to both states, Bahrain's relationship with Israel has been much smoother than that of the UAE. This reality is underpinned by the Jewish community based in Al-Qatif and its integration, which has translated into full and active participation in Bahrain's political life. This has helped to ensure that relations between Manama and Jerusalem have been far from conflictual.

Despite being seen as a novelty in the eyes of the general public, the truth is that the recent agreement is the third 'peace treaty' that signature has reached between the Hebrew country and an Arab nation. However, it is the first that seems to have been born with sufficiently solid foundations to augur a new, much more stable and lasting status , in clear contrast to the relations resulting from the previous agreements with Egypt and Jordan, which were very limited to personal relations and in the field of security and conventional diplomacy.

The new agreement with Israel sets out a new path for partnership affecting the Middle East as a whole, including substantially counterbalancing Iran's influence, fostering trade relations, tourism, partnership in subject military intelligence sharing, cooperation in health area and thereby helping to position the UAE to lead Arab diplomacy in the region by offering a solid civil service examination to Islamist groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood and its Palestinian arm in Gaza, Hamas, and thereby opening the door for other countries in the region to move in the same direction.

Israel's decision to fail the announced annexation under its sovereignty of certain areas of the West Bank is test that these moves in the region are much deeper and much more prepared and agreed in advance than might be imagined.

And this is precisely one of the major differences with previous agreements. The great expectation that has been created and the clear indications that other countries, including Saudi Arabia, will follow the UAE's lead.

In fact, one significant step in this direction was taken, and it was as simple as an Israeli "EI-Al" plane flying over Saudi airspace carrying a large issue group of businessmen, staff officials and investors on its way to the Emirates as a gesture of goodwill. And contrary to what might have been expected at other times, this had no repercussions in the Arab world, nor did it provoke any protests or demonstrations against it, subject .

Places such as Amman, Beirut, Tunis and Rabat, where demonstrations against the Israeli "occupation" and similar accusations are traditionally large in terms of participation, remained largely calm on this occasion.

But if this has gone unnoticed by the general population, it has not gone unnoticed by the leaders of the Middle Eastern powers and the violent organisations they use as proxies.

For those aspiring to follow in the UAE's footsteps and establish relations with Israel, this has served as a spur to reaffirm their decision, as the sense of unease or even danger emanating from the streets in the Arab world regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that such a move might provoke has diminished.

For Iran and its proxies , on the other hand, it has been a hard lesson. Not only has the Palestinian cause, which has been raised and put on the table for so long, been significantly diminished in importance, but it has coincided in time with potestas in both Iraq and Lebanon in the opposite direction, i.e. against Iran's interference in the internal affairs of both countries.

In conclusion, it should be noted that, while this absence of protest at the agreement between Israel and the UAE may seem surprising, it is a clear sign of a long process of political maturation and evolution within the Arab world at large.

The people of the Middle East in general no longer aspire to pan-Arabist, pan-Islamic unity, to the establishment of the Great Caliphate or, in the case of Iran or Turkey, to imperialist dreams that are a thing of the past. What the mass of the people and society really want is to improve their well-being, to have more and more attractive economic opportunities, to have a good system educational, to improve the standards of development in all areas, to have the rule of law, and for the rule of law to be equal for all in their respective countries.

The treaty that is the subject of this point fits perfectly within these aspirations and this mental outline . The masses that once took to the streets no longer believe that the Palestinian cause is worthy of more effort and attention than their own struggle for a better future for their nations.

And, importantly, despite the opacity of the ayatollahs' regime, Iran's population is becoming less and less submissive to policies that are leading the country into a series of permanent conflicts with no end in sight, wasting the country's resources to sustain them.

Just two days after advertisement of agreement , the United Arab Emirates lifted the ban on telephone communication with Israel, with Hebrew Foreign Minister Gabi Ashkenazi and his Emirati counterpart Abdullah binZayed symbolising the opening of this new line of communication.

Almost immediately afterwards, a team from the Israeli Foreign Ministry travelled to Abu Dhabi to begin looking for possible sites for the future Israeli embassy.

A significant flow of investment from the UAE is being channelled to Israeli companies seeking new ways to treat COVID19 and to develop new tests to detect the disease. The increase in business deals between Israeli and Emirati companies has been almost immediate, and the "El-Al" company is already working to open a direct corridor between Tel Aviv and Abu Dhabi.

In view of the new status and the new approaches, Morocco, Oman and other Arab countries are now moving to follow in the UAE's footsteps. Israel's attractiveness is only growing, in a significant evolution from being the most hated country in the region to the most desired partner .

One factor to consider, however, is the impact in the US and Europe. In the West, the Palestinian cause is generally gaining support mainly due to the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. As such, changes in relations with Israel are likely not only to fail to undermine that support, but also to spur increased efforts to prevent normalisation through disinformation campaigns spreading hatred towards Israel.

Finally, the civil service examination by Turkey, Qatar and Iran was predictable, but also clarifying. The Iranian president has called agreement a "grave mistake", while his Turkish counterpart has threatened to close the UAE embassy in Turkey. status In both cases, the ultimate reason for this reaction is the same: the use of the Palestinian cause for their own interests and, coincidentally, both are on this occasion coincidental: to distract public opinion from the difficult economic situation that, for different reasons, the two countries are going through.

Regional policy

The most important and enduring element of the UAE's foreign and security policy is its strategic alliances with the US and Saudi Arabia. Although the UAE has pursued a more independent course over the past decade, developments and this new direction would not have been possible without the support of the US, on whose protection the small but wealthy yet sparsely populated state relies, and who can be counted on to export its energy resources in the event of a conflict.

Even during the Obama administration, when relations were strained by US policy towards the events of the 'Arab Spring' and Iran, the strategic alliance between the two nations was maintained.

The clearly defined anti-Iranian policy of Donald Trump's administration, equivalent to that of the UAE, facilitated a rapid improvement in relations once again, and the new US administration saw the UAE as a fundamental pillar on which to base its Middle East policy. Thus, together with Israel and Saudi Arabia, the UAE is now the main US ally in the region.

In contrast to the US, Saudi Arabia became a strategic partner of the UAE's new regional policy under Obama. Indeed, the two nations have maintained close ties since the birth of the Emirates in 1971, but the new, young state unsurprisingly remained in the shadow of the other, more established nation, following the policies of its 'big brother'.

This status changed with the rise to power of Mohammed Bin Zayed who, since 2011, has been committed to spearheading a political line of joint actions in the region that have ultimately been decisive. MbZ found his perfect counterpart in Saudi Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, who gradually, since 2015, took the reins as the visible head of Saudi Arabia's policy. To such an extent that in certain cases, such as Yemen and Qatar, the UAE's leadership and drive seems to have been the unifying force behind joint regional policies.

Alliances

United States

The US role as an ally of the UAE dates back to the early 1980s, just after the 1979 Iranian revolution, which resulted in the loss of its most important ally in the region and the beginning of the Iran-Iraq war.

However, it was the 1990-1991 Gulf War that, with Iraq's invasion of Kuwait on 2 August 1990, showed the UAE how vulnerable the small Gulf states were to military aggression by any of their powerful neighbours.

In order to ensure its protection, and in common with other countries in the region, the UAE favoured an increased US presence on its territory in the years following the war. This concluded with a bilateral security agreement, agreement , signed in July 1994. This gave the US access to the UAE's air and seaports instructions and, in return, it undertook to protect the country from external aggression. Interestingly, and as a measure of how status has evolved, the agreement remained secret at Abu Dhabi's request because of the UAE's fear of criticism and protest both domestically and from Iran.

Initially, the UAE was no more than a US ally in the Persian Gulf. However, its importance as partner grew between 1990 and 2000, in part due to the port of Jebel Ali, which became the US Navy's most used base outside the country, and the Al Dhafra air base, a facility core topic for US activities in the region.

Moreover, since the late 1990s, the UAE has begun a process of presenting itself to its new ally as a reliable and more relevant partner , increasing the quantity and level of its cooperation. framework In line with this, UAE military forces have participated in all major US operations in the Middle East, from the Gulf War in 1991 to Somalia in 1992, Kosovo in 1999, Afghanistan since 2002, Libya since 2011, and Syria (in the fight against Da'esh) between 2014 and 2015. Only the UAE's participation in the invasion of Iraq in 2003 was vehemently avoided. From this involvement, the UAE Armed Forces have gained a great deal of experience on the ground, which has been beneficial to their effectiveness and professionalism.

This involvement in the often controversial US military actions in Arab countries has undoubtedly been a key element for the United States. Not only because of the image and narrative implications of having at least one Muslim country supporting them, but also because Abu Dhabi's contribution has not been limited to the military aspect. Humanitarian organisations have acted in parallel in order to win the support of the population wherever they have intervened by investing huge amounts of money. The most obvious example is Afghanistan, where the UAE has spent millions of dollars on humanitarian projects and development to help stabilise the country, while providing a small contingent of special operations forces in the particularly dangerous southern part of the country since 2003. In addition, between 2012 and 2014 they expanded their deployment with six F16 aircraft to support air operations against the Taliban. Even when the US began its phased withdrawal after 2014, Emirati troops remained in Afghanistan.

Getting the UAE on board in the fight against jihadists was not difficult at all, as its leaders are particularly averse to any form of religious extremism that affects the political system within Islam. This is the main reason for its air force's involvement in the US-led coalition against Daesh in Syria between 2014 and 2015. To such an extent that, after the US aircraft, it was the UAE aircraft that flew the most sorties against jihadist targets.

But partnership was not limited to the US. Both Australia and France had the emirates' air instructions at their disposal to carry out their operations.

Only the open breakdown of hostilities and the UAE's involvement in the 2015 Yemen War reduced its involvement in the fight against Daesh.

But it has not all been easy. The 2003 invasion of Iraq caused deep misgivings in the UAE, which saw it as a grave mistake. Their fear was that such an intervention would end up increasing Iran's influence over Iraq, or lead to civil war, which would destabilise the entire region.

Fears were realised when in 2005 a Shiite coalition close to Iran won the Iraqi elections and war broke out, leaving the UAE with its hands tied to try to influence status. Their main concern at the time was that a premature withdrawal of all US forces would further complicate status.

The renewed relationship with the Trump administration has led to the signature of a new security and cooperation agreement signed in 2017. reference letter In contrast to what happened in 1994, the contents of the agreement have been made public, and mainly relate to the presence of US troops on Emirati soil on a permanent basis. The agreement also covers the training of Emirati armed forces and regular joint exercises.

Thanks to this agreement, the US presence in the UAE is larger than ever. There are currently some 5,000 men deployed between the Al Dhafra airbase, the port of Jebel Ali and a few other small instructions or naval stations. At Al Dhafra air base alone, 3,500 men operate from F-15, F-22 and F-35 fighter jets, reconnaissance aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

For its part, the UAE has continued to develop its own military capabilities by acquiring US-made material, mainly anti-aircraft systems ("Patriot" and THAAD) and combat aircraft (110 F-16s). In addition, for a couple of years now, the UAE has shown great interest in acquiring the new F-35, although negotiations, not without some reluctance, are still ongoing.

In 2018, problems arose in supplying precision-guided munitions to both the UAE and Saudi Arabia, as both countries were using them in the Yemen War. The murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Kashoggi exacerbated resistance from the US congress , forcing President Trump to use his veto power in order to maintain the supply. This gives a measure of how decisive the current administration's attitude towards both countries is.

Despite all the difficulties mentioned above, the current US administration has redoubled its efforts to support the UAE in its regional policies, as they coincide with US objectives.

The first goal has been to build an anti-Iran alliance among Middle Eastern states that includes the UAE as partner core topic along with Saudi Arabia and Egypt. This plan is entirely in line with Abu Dhabi's aspiration to gain some leadership in the region, and is likely to succeed, as the UAE is likely to support the US in a solution to the Palestinian conflict that is quite in line with the Israeli proposal .

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is currently the UAE's most important ally in the region. Both states are financed by oil exports and both are equally wary of the expansionist ambitions of their powerful neighbours, especially Iran.

However, despite this alliance, the UAE has long feared that Saudi Arabia, using its unequal size in terms of population, military strength and oil production capacity, would seek to maintain a hegemonic position in the Persian Gulf.

In 1981, the Persian Gulf countries seized the opportunity to create an alliance that excluded the then major regional powers. Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE created the committee Cooperation for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC). This committee had a joint military force that never grew to any significant size. The biggest test of the GCC's weakness and ineffectiveness was Iraq's invasion of Kuwait without civil service examination by the supranational body.

As result of the above, the UAE relied on the US for its protection, the only country with both the will and the capacity to carry out the task of defending the small state against potential foreign aggression.

The consequence at the regional level is marked by the convergence of interests of Saudi Arabia and the UAE which, between 2011 and 2019, have pursued common regional political objectives, relying if necessary on their military capabilities.

For example, Bahrain's request for financial aid to the GCC in 2011 when its rulers felt threatened by Shia protest movements. However, its most significant intervention was its support for the coup d'état in Egypt against President Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood in 2013.

India

Socio-political and economic relations between the GCC members and India have always been very close, and have been based on the understanding that a secure and stable political and social environment in the Persian Gulf and Indian subcontinent are critical factors for the respective countries' development and their trans-regional ties.

From India's perspective, the improvement of its technological and economic development goes hand in hand with New Delhi's ability to strengthen its partnerships around the world. In this regard, the Persian Gulf countries, and especially the UAE, are seen as a bridge to knowledge, capabilities, resources and markets to enhance that development.

In 2016, the hitherto bilateral relations between the two countries were formalised in a strategic cooperation agreement called CSP(Comprehensive Strategic Partnership).

For the UAE, India is a modern country, a political phenomenon independent of the West that maintains strong religious and traditional roots without renouncing its diversity. In some ways, and with some reservations, it is a mirror for the UAE.

The agreement cooperation is cross-cutting and covers issues as diverse as counter-terrorism, exchange information and intelligence, anti-money laundering measures, cyber-security, as well as cooperation on subject defence, financial aid humanitarian, etc.

On the more economic side, the initiative includes concrete actions to facilitate trade and investment, with the UAE committing goal $75 billion to support the development of new generation infrastructure in India, especially railways, ports, roads, airports and industrial parks.

With regard to the energy sector, the agreement envisages the UAE's participation in the modernisation of the oil sector in all its branches, taking into account the development of a strategic reservation .

The part dealing with the development of technology for the peaceful use of nuclear energy, as well as cooperation in the aerospace sector including the development and joint launching of satellites, as well as the necessary ground control infrastructure and all necessary applications, is very significant.

Today, India has growing and multifaceted socio-economic ties with both Israel and the Persian Gulf countries, especially the UAE. The diaspora of Indian workers in the Gulf accounts for annual remittances of nearly $50 billion. Trade relations bring in more than $150 billion to India's coffers, and almost two-thirds of India's hydrocarbon needs come from the region. It is therefore evident that the new status is viewed with special interest from this part of the world, assessing opportunities and possible threats.

Clearly, any such agreement that at least a priori brings more stability and a normalisation of relations will always be beneficial, but its weaknesses and the possible evolution of status must also be taken into account.

Thus, from a geopolitical point of view, India has welcomed the re-establishment of relations between the UAE and Israel, as both are strategic partners.

The new landscape that is opening up between Israel and the GCC seems to bring a moderate and consistent solution to the Palestinian problem closer, making it much easier for Indian diplomacy to work .

But one must be cautious, and especially in this part of the world nothing is of one colour. This hopeful agreement could have a perverse effect, further polarising the jihadist sectors of the Arab world and pitting them even more against each other.

The possibility of the Persian Gulf region becoming the new battleground where Iranian and Israeli proxies clash cannot be completely ruled out, especially in Shia-controlled areas. However, this is not a likely option for the time being.

But for India it is even more important to manage the economic implications of the new treaty. With defence and security cooperation as key pillars, both sides are now beginning to contemplate the real economic potential of complementing their economies.

Reactions to the treaty: scenarios

Faced with an event as important as the one described above, it is to be expected that there will be reactions in various directions, and depending on these, the evolution of status may be different.

Actors likely to play a role in the different scenarios include the UAE and the new alliance, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, Palestine and the Muslim Brotherhood.

It should not be forgotten that the background to this treaty is economic. subject If its development is successful, it will bring stability to a region that has long been punished by all kinds of conflicts and clashes, and will lead to an exponential increase in trade operations, technology transfer and the opening of new routes and cooperation, mainly with Southeast Asia.

The role of the US will be decisive in any of the scenarios that may arise, but in any of them its position will be to minimise physical presence and support the signatories of the treaty with political, economic and defence actions through the supply of military materiel.

The treaty has a strong economic component fixed on the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. This is but one more sign of how the world's geopolitical centre of gravity is shifting to the Asia-Pacific region and this is one of the main reasons for the US's unconditional support.

Members of the UAE government have traditionally viewed more radical Islamist ideologies and policies as an existential threat to the country's core values. Both the Shiite sectarian regime in Iran and the Sunni Muslim Brotherhood, group , are seen as a constant threat to the stability of the region's powers.

For the UAE these transnational movements are a catalyst for radicalism across the region.

In view of the above, the following scenarios are plausible:

Scenario 1

For the moment, the Palestinians are the ones whose interests have been most harmed by the new status . Prominent figures in Palestinian society, as well as senior officials of the Palestinian Authority, have considered the new treaty a betrayal. As mentioned, the Palestinian issue is taking a back seat in the Arab world.

If, as is predicted, more countries join the new treaty in the coming months, the Palestinian Authority may try by all means to bring its demands and struggle back to the forefront. To this end, it would count on the support of Iran and its proxies and Turkey. This status would begin by delegitimising the governments of the countries that have aligned themselves with the UAE and Israel through a strong information campaign at all levels, with massive use of social networks in order to mobilise the most sensitive and pro-Palestinian population. The goal would be promote demonstrations and/or revolts that would create doubts among those who have not yet joined the pact. These doubts could lead to a change of decision or delay in new accessions, or these new treaty candidates could increase the Palestinian-related conditions for joining the treaty. This option is likely to be the most dangerous because of the possibility of internal dissension or disputes that could lead to an implosion of the pact.

It can be considered a likely scenario of intensity average/leave.

Scenario 2

The position that Saudi Arabia takes is core topic. And it will be decisive in gauging Iran's reaction. In the Middle East ecosystem, Iran is the power that has the most to lose from this new alliance. The struggle for hegemony within the Muslim world cannot be forgotten. And this struggle, which is also a religious one, pitting Shiites against Sunnis, has Iran and Saudi Arabia as its main protagonists.

Saudi Arabia is likely to join the treaty, but given the status, and in an attempt not to further strain relations with its main enemy, it may decide not to join the treaty, but to support it from the outside with specific or bilateral agreements. This would always be done with the rest of the Arab member countries, which would act as a bridge for its relations with Israel. It would be a way to wash its face and avoid express recognition of the state of Israel or direct relations with it. It should be borne in mind that there are pockets of Shiite majority in the country that could be spurred on by Iran.

However, in a worst-case scenario, Iran will react through its proxies, stepping up its activity in Yemen, trying to promote protests and revolts inside Saudi Arabia, reinforcing its support for Hamas in Palestine and Hezbollah in Lebanon and even its militias in Iraq.

Support for the protests that have already taken place in Sudan will also be part of this campaign. Sudan is a very unstable country, with a very weak Structures of power that is unlikely to be able to quell high-intensity revolts.

The goal would be to inflame the region under the cover of support for the Palestinian people in order to dissuade further accessions to the treaty, as well as undermine the treaty's effectiveness, giving the image of instability and insecurity in the region. This will discourage potential investors from approaching the UAE, attracted by the enormous economic possibilities it offers, while keeping Saudi Arabia occupied with its southern flank and its internal problems. Some action without a clear or acknowledged perpetrator against vessels transiting the Gulf, as has already happened, or the boarding of one by Iranian forces under any subject accusation or legal ruse, cannot be ruled out. Direct actions involving Iranian forces are unlikely.

Turkey may become involved by providing weapons, technology and even mercenary fighters to any of the factions acting as Iran's proxy.

This scenario can be considered as possible and of intensity average

Scenario 3

Iran needs either the governments or the populations of the various Middle Eastern countries to continue to see Israel as its main enemy and threat. Among other reasons because it is a narrative for domestic consumption that it uses recurrently to divert the attention of its own population from other subject problems. So far, the unifying element of this view of Israel has been the Palestinian conflict. It is therefore likely that actions will be taken that provoke a reaction from Israel. These actions may come from within the state of Israel itself, from Palestinian or Lebanese territory, always at position from Iran's proxies. A provocation that would result in an Israeli attack on Arab territory, most likely against Iran or Syria, cannot be ruled out: result . The final goal would not be the Hebrew state but undermining the instructions of the treaty, creating social unrest among the signatories, preventing Saudi Arabia's accession and being able to use the Palestinian conflict in its own interests.

This is a possible, high-intensity scenario.

Conclusions

The UAE's emergence as an emerging geopolitical power in the Middle East has been as surprising as it has been precipitous, as not so long ago international observers did not give much hope for the life of the new federation of small states that had just come into being.

By contrast, the UAE and Abu Dhabi, its largest and most prosperous emirate, in particular, has been increasing its position over the last decade, playing a decisive role in the region. To such an extent that, to this day, the UAE's actions are seen as having facilitated to some extent the changes we are witnessing.

Western policymakers are generally dazzled by the UAE's perceived liberalism and the ability of its elites to speak both literally and figuratively their own language. It is important that they familiarise themselves with the UAE's model in all its aspects and, importantly core topic, that they understand that Abu Dhabi expects to be treated by all as an equal. Dealing with the UAE in this way and considering it a robust and reliable partner also means sending them the message of a clear intention to support them.

One of the major consequences of this agreement may be to de-escalate the Palestinian conflict, if not end it, then permanently limit it. For generations, this conflict has been used by political and religious leaders across the Arab and Muslim world to distract their attention from other issues. It was an easy and readily available resource . But it is now recognised that it is a territorial dispute between two peoples, and future negotiations have no choice but to go down that road, with the focus on the outdated Palestinian leadership.

There is the not inconsiderable possibility that the agreement agreement could have a domino effect, leading other states in the region to follow in the UAE's footsteps, which in some cases would only mean publicising the de facto relations they already have with the state of Israel. In this sense, talks between Oman's foreign minister and his Israeli counterpart are known to have taken place just after the signature treaty with the UAE was signed.

The Israeli prime minister also held a meeting meeting with Sudanese leader Abdel Fattah Burhan, which could be a sign of upcoming moves on that flank as well.

Although the leak had consequences for a senior Sudanese official, the government did not deny the contacts. And it has all been confirmed when the US, advertisement of Sudan's forthcoming removal from the list of countries sponsoring terrorism, has followed the agreement between Israel and Sudan to normalise diplomatic relations.

For years, US policy has been to demilitarise its position in the Middle East; the cost of its presence has been very high compared to the benefits it brings, as well as generating some animosity. Both the US and other G8 members support the UAE as the region's economic leader. This support provides them with the ideal position to deploy their economic interests in the region(commodities, research and development & investment).

This position of US/UAE support (plus some G8 countries), strengthens the Arab country's role in the region at subject political and by default military, and in a way allows its new allies and supporters to have some influence in organisations such as OPEC, GCC, Arab League) and in neighbouring countries, but from a more Arab and less Western position.

On the issue of the UAE's purchase of the F-35, it is undeniable that this issue makes Israel uncomfortable despite the change in relations. The main reason for this is the fear of an equalisation in military capabilities that could be dangerous. However, this will not be an obstacle to progress on future peace agreements and on development of this one. Such a major operation would take years to materialise and by then, relations between Jerusalem and Abu Dhabi will have been consolidated. Indeed, it might even be welcomed by Israel, as it would strengthen its military capabilities vis-à-vis its main opponents in the region.

It is increasingly apparent in the Arab world that Israel is too small to harbour imperialist aspirations, in contrast to countries such as Turkey and Iran, both of which formed former empires, and which seem intent on trying to restore what they once achieved or were.

Instead, Israel is increasingly seen as a strong, prosperous and dynamic enough country that cooperation with Jerusalem is a smart move that can provide benefits to both sides.

The agreement between Israel and the UAE may have been driven in part by their fear of Iran's advances and the danger it poses. But the benefits to them go far beyond that issue.

These extend to economic investment possibilities, finance, tourism and especially the sharing of know-how. The UAE can benefit from Israel's technological and scientific edge just as Israel can profit from the UAE's position as an international service centre and a key gateway to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. entrance .

In relation to the entrance gateway to the Indian subcontinent, it should be noted that for India the most important part of agreement is to manage the economic side of the synergies caused by it.

The UAE and Bahrain can become intermediaries for Israeli exports of both commodities and services to various parts of the world.

Israel has a strong defence, security and surveillance equipment industry. It is a leader in dryland farming, solar energy, horticulture, high-tech jewellery and pharmaceuticals.

Moreover, Israel has the capacity to provide highly skilled and semi-skilled labour to GCC countries, especially if they come from Sephardic and Mizrahi ethnic groups, many of whom speak Arabic. Even Israeli Arabs can find opportunities to help further build ties and bridges across the cultural divide.

Israel's incursion into the Gulf has the potential to influence the political-economic architecture that India has been building for years, being, for example, one of the largest suppliers of labour, foodstuffs, pharmaceuticals etc.

The largest customers in Dubai's real estate market, as well as the largest issue of tourists visiting the country, come from India. But in this changing scenario there is scope for three-way synergies, making India a major player in this.

The final conclusion that can be drawn by way of evaluation for the future is that this new relationship will undoubtedly be a model for other Sunni states to follow, transforming a region mired in 19th century conflicts into one of the power centres of the 21st century.

* Lieutenant Colonel of Infantry. Geopolitical Analyst

REFERENCES

Acharya, Arabinda, 'COVID-19: A Testing Time for UAE-India Relations? A Perspective from Abu Dhabi", Strategic Analysis, September 2020.

Arab Center for Research and Policy studies, 'The Abraham Agreement: normalization of relations or announcement of an existing Emirati - Israeli alliance? Qatar, August 2020.

Karsh, Ephraim, ed., "The Israel-UAE Peace: A Preliminary Assessment", Ramat Gan: The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, cafeteria-Ilan University, September 2020.

Salisbury, Peter, "Risk Perception and Appetite in UAE Foreign and National Security Policy", The Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House Middle East and North Africa Programme, London: July 2020.

Steinber, Guido, "Regional Powers, United Arab Emirates", German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, July 2020.

The Trump Administration concludes its management in an assertive manner in the region and passes the baton to the Biden Administration, which seems to be committed to multilateralism and cooperation.

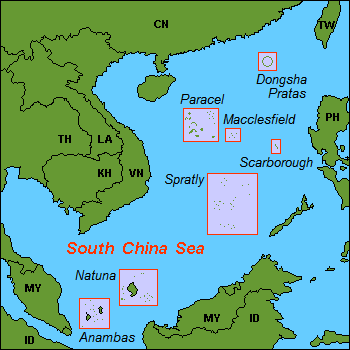

With the world at a standstill due to Covid-19, the Asian giant has taken the opportunity to resume a whole series of operations with the aim of expanding its control over the territories around its coastline, goal . Such activities have not left the United States indifferent, and despite its internal status complex, it has taken matters into its own hands. With Mike Pompeo's visits throughout the Asia-Pacific, the US has stepped up the process of containing Beijing, which has taken the form of a quadruple alliance between the United States, Japan, India and Australia. The new executive that the White House will inaugurate in January may involve a renewal of US action that, without breaking with the Trump Administration, recovers the spirit of the Obama Administration, that is, guided by greater cooperation with the countries of the Asia-Pacific and a commitment to dialogue.

![Airstrip installed by China on Thitu or Pagasa Island, the second largest of the Spratlys, whose administration has been internationally recognised for the Philippines [Eugenio Bito-ononon Jr]. Airstrip installed by China on Thitu or Pagasa Island, the second largest of the Spratlys, whose administration has been internationally recognised for the Philippines [Eugenio Bito-ononon Jr].](/documents/16800098/0/mar-china-blog.jpg/221fc42a-0d93-e77e-fb3e-4aac0a9ecef0?t=1621874942557&imagePreview=1)

Airstrip installed by China on Thitu or Pagasa Island, the second largest of the Spratlys, whose administration has been internationally recognised for the Philippines [Eugenio Bito-ononon Jr].

article / Ramón Barba

During the pandemic, Beijing has taken the opportunity to resume its actions in Asia Pacific waters. In mid-April, China proceeded to designate land in the Spratly Islands, the Paracel Archipelago and Macclesfield Bank as new districts of the city of Sansha, a town on China's Hainan Island. This designation management assistant caused subsequent protests from the Philippines and Vietnam, who claim sovereignty over these areas. Beijing's attitude has been accompanied by incursions and sabotage of ships in the area. See the sinking of a Vietnamese fishing boat, which China denies, arguing that it had suffered an accident and was carrying out illegal activities.

China's actions since the summer have been increasing instability in the region through military exercises near Taiwan or confrontations with India due to its border problems; on the other hand, in addition to the Philippine and Vietnamese civil service examination towards Chinese movements, there is growing tension with Australia after the latter requested an investigation into the origin of the COVID-19, and the increase in maritime tensions with Japan. All this has led to a response from the United States, which claims to be a defender of free navigation in the Asia-Pacific, justifying its military presence by emphasising that the People's Republic of China is not in favour of free transit, democracy or the rule of law.

US makes a move

Tensions between China and the US over the current dispute have been on the rise throughout the summer, with both increasing their military presence in the region (Washington has also sanctioned 24 Chinese companies that have helped militarise area). All of this has recently been reflected in Secretary of State Mike Pompeo's visits to the Asia-Pacific in October. Prior to this round of visits, he had made statements in September at the ASEAN Virtual Summit urging countries in the region to limit their relations with China.

The dispute over these waters affects Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Brunei and Malaysia, countries which, along with India and Japan, were visited by Pompeo (among others) in order to ensure greater control over Beijing's actions. During his tour, the US Secretary of State met with the foreign ministers of India, Australia and Japan to join forces against the Asian giant. Washington then signed in New Delhi a military agreement of exchange of data satellites to better track Chinese movements in the area, and made a state visit to Indonesia visit . It should be recalled that Jakarta had so far been characterised by a growing friendship with Beijing and a worsening relationship with the US over a decrease in Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) aid. However, during Pompeo's visit , the two countries agreed to improve their relations through greater cooperation in regional, military procurement, intelligence, joint training and maritime security.

This move by Washington has therefore implied:

-