Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Central Europe and Russia .

Narratives from the Kremlin, the Duma and nationalist average embellish Russia's history in an open culture warfare against the West.

Russian average and politicians, influenced by a nationalist ideology, often use Russian history, particularly from the Soviet time, to create a national consciousness and praise themselves for their contributions to world affairs. This often results in manipulation and in a rising hostility between Russia and other countries, especially in Eastern Europe.

A colored version of the picture taken in Berlin by the network Army photographer Yevgueni Khaldei days before the Nazi's capitulation

ARTICLE / José Javier Ramírez

average bias. Russia is in theory a democracy, with the current president Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin having been elected through several general elections. His government, nonetheless, has been accused of restricting freedom of opinion. Russia is ranked 149 out of 179 countriesin the Press Freedom Index, so it is no surprise that main Russian average (Pravda, RT, Sputnik News, ITAR-TASS, ...) are strong supporters of the government's version of history. They have been emphasizing on Russia's glorious military history, notoriously since 2015 when they tried to counter international rejection of the Russian invasion of Crimea appealing to the spirit of the 70th World War II anniversary. On the other side, social networks are not often used: Putin lacks a Twitter account, and the Kremlin accounts' posts are not especially significant nor controversial.

Putin's ideology, often called Putinism, involves a domination of the public sphere by former security and military staff, which has led to almost all average pursuing to justify all Russian external aggressions, and presenting Western countries, traditionally opposed to these policies, as hypocritical and Russophobic. Out of the remarkable exceptions to these pro-government public sphere, we might mention Moscow Today newspaper (whose ideology is rather independent, in no way an actual opposition), and the leader of the Communist faction, Gennady Andreyevich Zyuganov, who was labelled Putin several times as a dictator, without too much success among the electorate.

Early period. Russian average take pride in having an enormously long history, to the extent of having claimed that one of its cities, Derbent, played a key role in several civilizations for two thousand years. However, the first millennium of such a long history often goes unmentioned, due to the lack of sources, and even when the role of the Mongolian Golden Horde is often called into question, perhaps in order to avoid recognizing that there was a time where Russians were subjected to foreign domination. In fact, Yuri Petrov, director of RAS Russian History Institute, has refused to accept that the Mongolian conquest was a colonization, arguing that it was a process of mixing with the Slavic and Mongolian elites.

Such arguments do not prevent TASS, Russian state's official average, from having recognized the battle of Kulikovo (1380) as the beginning of Russian state history, since this was the time where all Russian states came together to gain independence. Similarly, Communist leader Zyuganov stated that Russia is to be thanked for having protected Europe from the Golden Horde's invasion. In other words, Russian average have a contradictory position about the nation's beginning: on one hand, they deny having been conquered by the Mongolian, or prefer not to mention such a topic; on the other, they widely celebrate the defeat of the Golden Horde as a symbol of their freedom and power. Similar contradictions are quite common in such an official history, dominated by nationalist bias.

Czarism. Unlike what might be thought, Russian Czars are held in relative high esteem. Orthodox Church has canonized Nicolas II as a martyr for the "patience and resignation" with which he accepted his execution, while public polls carried by TASS argued that most Russians perceive his execution as barbaric and unnecessary. Pravda has even argued that there has been a manipulation of the last Czar's story both by Communists and the West (mutual accusations of manipulation between Russian and Western average are quite common): according to Pyotr Multatuli, a historian interviewed by Pravda, the last Czar was someone with fatherly love towards its citizens, and he just happened to be betrayed by conspirators, who killed him to justify their legitimacy.

But this nostalgic remembrance is not exclusive solely to the last Czar, there are actually multiple complimentary references to several monarchs: Peter the Great was credited by Putin for introducing honesty and justice as the state agencies principles; Catherine the Great for being a pioneer in experimentation with vaccines, and she was even the first monarch to have been vaccinated; Alexander III created a peaceful and strong Russia... Pravda, one of the most pro-monarchy newspapers, has even argued that Czars were actually more responsible and answerable to society than the USA politicians, or that Napoleon's invasion was not actually defeated by General Winter, but by Alexander I's strategy. The appreciation for the former monarchy might be due to the disappointment with the Soviet era, or in some way promoted by Putin, who since the Crimean crisis inaugurated several statues to honour Princes and Czars, without recognizing their tyranny. This can be understood as a way of presenting himself as a national hero, whose decisions must be obeyed even if they are undemocratic.

USSR. The Soviet Union is the most quoted period in the Russian average, both due to their proximity, and because it is often compared to today's government. Perceptions about this period are quite different and to some extent contradictory. Zyuganov, the Communist leader, praises the Soviet government, considering it even more democratic that Putin's government, and has advocated for a re-Stalinisation of Russia. Nonetheless, that is not the vision shared neither by Putin nor by most average.

Generally speaking, Russian average do not support Communist national policy (President Putin himself once took it as "inappropriate" being called neo-Stalinist). There is a recognition of Soviet crimes while, at the same time, they are accepted as something that simply happened, and to what not too much attention should be drawn. Stalin particularly is the most controversial character and a case of "doublethink": President Putin has attended some events to honour Stalin's victims, while at the same time sponsored textbooks that label him as an effective leader. The result, shown in several polls, is that there is a growing indifference towards Stalin's legacy.

However, the approach is quite different when we talk about the USSR foreign policy, which is considered completely positive. The average praise the Russian bravery in defeating Nazi Germany, and doing it almost alone, and for liberating Eastern Europe. This praise has even been shown in the present: Russian anti-Covid vaccine has been given the name of "Sputnik V", subtly linking Soviet former military technology and advancement to the saving of today's world (the name of the first artificial satellite was already used for the news website and broadcaster Sputnik News). Moreover, Putin himself wrote an essay on the World War II where he argued that all European countries had their piece of fault (even Poland, whose occupation he justifies as politically compulsory) and that criticism of Russia's attitude is just a strategy of Western propaganda to avoid accepting its own responsibilities for the war.

This last point is particularly important in Russian average, who constantly criticize Western for portraying Russia and the Soviet Union as villains. According to RT, for instance, Norway should be much more thankful to Russia for its help, or Germany for Russia's promotion of its unification. The reason for this ingratitude is often pointed to the United States and its imperialism, because it has always feared Russia's strength and independence, according to Sputnik, and has tried to destroy it by all means. The accusations to the US vary among the Russian average, from Pravda's accusation of the 1917 Revolution having been sponsored by Wall Street to destabilize Russia, to RT's complaint that the US took advantage of Boris Yeltsin's pro-Western policies to impose severe economic measures that ruined Russian economy and the citizens' well-being (Pravda is particularly virulent towards the West).

What the European neighbours think. As in most countries, politicians in Russia use their national history mostly to magnify the reputation of the nation among the domestic public opinion and among international audiences, frequently emphasizing more the positive aspects than the negative ones. What distinguishes Russian average is the influence the Government has on them, which results in a remarkable history manipulation. Such manipulation has arrived to create some sort of doublethink: some events that glorify Russia (Czars' achievements, Communist military success, etc.) are frequently quoted and mentioned while, at the same time, the dark side of these same events (Czars' tyranny, Stalin's repression, etc.) is ignored or rejected.

Manipulated Russian history is often incompatible with (manipulated or not) Western history, which has led to mutual accusations of hypocrisy and fake news that have severely undermined the relations between Russia and its Western neighbours (particularly Poland, whom Russia insists to blame to some extent for the World War II and to demand gratitude for the liberation provided by Russia). If Russia wants to strengthen its relationships, it must stop idealizing its national history and try to compare it with the Western version, particularly in topics referring to Communism and the 20th century. Only this way might tensions be eased, and there will be a possibility of fostering cooperation.

A separate chapter on this historical reconciliation should be worked with Russia's neighbours in Eastern Europe. Most of them shifted from Nazi occupation to Communist states, and now they are still consolidating its democracies. Eastern Europe societies have mixed feelings of love and rejection towards Russia, what they don't buy any more is the story of the network Army as a force of liberation.

[Angela Stent, Putin's World: Russia Against the West and with the Rest. Twelve. New York, 2019. 433 p.]

review / Ángel Martos

Angela Stent, director of Georgetown University's Center for Eurasia, Russia and Eastern Europe programs of study , presents in this book an in-depth analysis of the nature of Russia at the beginning of the 21st century. In order to understand what is happening today, we sample first look at the historical outlines that shaped the massive heartland that Russian statesmen have consolidated over time.

Angela Stent, director of Georgetown University's Center for Eurasia, Russia and Eastern Europe programs of study , presents in this book an in-depth analysis of the nature of Russia at the beginning of the 21st century. In order to understand what is happening today, we sample first look at the historical outlines that shaped the massive heartland that Russian statesmen have consolidated over time.

Russia took advantage of the global showcase of the 2018 World Cup to present a renewed image. The operation to sell Russia's national brand had some success, as reflected in surveys: many foreign (especially American) spectators who visited the country for the football tournament came away with an improved image of the Russian people, and vice versa. However, what was presented as an opening to the world has not manifested itself in the Kremlin's domestic or international policy: Putin's grip on the hybrid regime that has ruled Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union has not been loosened in the slightest.

Many experts could not predict the fate of this nation in the 1990s. After the collapse of the communist regime, many thought Russia would begin a long and painful road to democracy. The United States would maintain its unique superpower status and shape a New World Order that would embrace Russia as a minor power, equal to other European states. But these considerations did not take into account the will of the Russian people, who understood Gorbachev's and Yeltsin's management as "historical mistakes" that needed to be corrected. And this perspective can be seen in Vladimir Putin's main speeches: a nostalgic feeling for Russia's imperial past, a refusal to be part of a world ruled by the United States, and the need to bend the sovereignty of the once Soviet republics. The latter is a crucial aspect of Russia's foreign policy that, to varying degrees, it has already applied to Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia and others.

What has changed in the Russian soul since the collapse of the Soviet Union? Have relations with Europe suffered ups and downs throughout the history of the Russian Empire? What are these relations like now that Russia is no longer an empire, having lost almost all its power in a matter of years? The author takes us by the hand through these questions. The Russian Federation as we know it today has been ruled by only three autocrats: Boris Yeltsin, Dmitry Medvedev and Vladimir Putin, although one could argue that Medvedev does not even properly count as president, since during his tenure Putin was the intellectual leader behind every step taken in the international arena.

Russia's complicated relations with European countries are notoriously exemplified in the case of Germany, which the book compares to a roller coaster (an expression that is particularly eloquent at Spanish ). Germany is the Federation's door to Europe, a metaphorical door that, throughout contemporary history, has been ajar, wide open or closed, as it is now. After the seizure of Crimea, Merkel's Germany's relations with Moscow have been strictly limited to trade issues. It is worth highlighting the huge differences that can be found between Willy Brandty's Ostpolitik and Angela Merkel's current Frostpolitik. Although Merkel grew up in East Germany, where Putin worked as a KGB agent for five years, and the two can understand each other in both Russian and German, this biographical link has not been reflected in their political relationship.

Germany went from being Russia's biggest European ally (to the extent that Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, after leaving position, was appointed after leaving position chairman of Rosneft's management committee ), to being a threat to Russian interests. After sanctions were imposed on Russia in 2014 with the support of the German government, relations between Putin and Merkel are at their worst. However, some might argue that Germany is acting hypocritically given that it has accepted and financed the Nordstream pipeline, which heavily damages Ukraine's Economics .

Besides the EU, the other main opponent for Russian interests is NATO. At every point on the map where the Kremlin wishes to exert pressure, NATO has strengthened its presence. Under US command, the organisation follows the US strategy of trying to keep Russia at bay. And Moscow perceives NATO and the US as the biggest obstacle to regaining its sphere of influence in "near abroad" (Eastern Europe, Central Asia) and the Middle East.

Putin's fixation with the former Soviet republics has by no means faded over time. If anything, it has increased after the successful annexation of the Crimean peninsula and the civil war that flared up in the Donbass. Russia's nostalgia for what was once part of its territory is nothing more than a pretext to try to neutralise any dissident governments in the region and subjugate as much as possible the countries that make up its buffer zone, for security and financial reasons.

The Middle East also plays an important role in Russian international affairs diary . Russia's main goal is to promote stability and combat terrorist threats that may arise in places that are poorly controlled by the region's governments. Putin has been fighting Islamic terrorism since the separatist threat in Chechnya. However, his possible good intentions in the area are often misinterpreted because of his support in every possible way (including aerial bombardment) for some authoritarian regimes, such as Assad's in Syria. In this particular civil war, Russia is repeating the Cold War proxy war game against the US, which for its part has been supporting the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Kurds. Putin's interest is to keep his ally Assad in power, along with the Islamic Republic of Iran's financial aid .

Angela Stent draws an accurate picture of Russia's recent past and its relationship with the outside world. Without being biased, she succeeds in critically summarising what anyone interested in security should bear in mind when addressing topic Russia's threats and opportunities. For, as Vladimir Putin himself declared in 2018, 'no one has succeeded in stopping Russia'. Not yet.

Georgian aspirations for EU and NATO membership meet Western fears of Russian overreaction

![View of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, with the presidential palace in the background [Pixabay]. View of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, with the presidential palace in the background [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/georgia-blog.jpg)

▲ View of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, with the presidential palace in the background [Pixabay].

ANALYSIS / Irene Apesteguía

In Greek times, Jason and the Argonauts set out on a journey in search of the Golden Fleece, with a clear direction: the present-day lands of Georgia. Later, in Roman times, these lands were divided into two kingdoms: Colchis and Iberia. From being a Christian territory, Georgia was conquered by the Muslims and later subjected to the Mongols. At this time, in the 16th century, the population was reduced due to continuous Persian and Ottoman invasions.

In 1783, the Georgian kingdom and the Russian Empire agreed to the Treaty of Georgiyevsk, in which the two territories pledged mutual military support. This agreement failed to prevent the Georgian capital from being sacked by the Persians, which was allowed by the Russian Tsar. It was the Russian tsar, Tsar Paul I of Russia, who in 1800 signed the corresponding incorporation of Georgia into the Russian empire, taking advantage of the moment of Georgian weakness.

After the demise of the Transcaucasian Federal Democratic Republic and thanks to the Russian collapse that began in 1917, Georgia's first modern state was created: the Democratic Republic of Georgia, which between 1918 and 1921 fought with the support of German and British forces against the Russian Empire. Resistance did not last, and occupation by the Russian Red Army led to the incorporation of Georgian territory into the Union of Soviet Republics in 1921. In World War II, 700,000 Georgian soldiers had to fight against their former German allies.

In those Stalinist times, Ossetia was divided in two, with the southern part becoming an autonomous region belonging to Georgia. Later, the process was repeated with Abkhazia, thus forming today's Georgia. Seventy years later, on 9 April 1991, the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic declared its independence as Georgia.

Every era has its "fall of the Berlin Wall", and this one is characterised by the disintegration of the former Russia. The major armed conflict that was to unfold in 2008 as a result of the frozen conflicts between Georgia and South Ossetia and Abkhazia since the beginning of the last century came as no surprise.

Since the disintegration of the USSR

After the break-up of the USSR, the territorial configuration of the country led to tension with Russia. Independence led to civil unrest and a major political crisis, as the views of the population of the autonomous territories were not taken into account and the laws of the USSR were violated. As twin sisters, South Ossetia wanted to join North Ossetia, i.e. a Russian part, with Abkhazia again following in their footsteps. Moscow recognised Georgia without changing its borders, perhaps out of fear of a similar action to the Chechen case, but for two long decades it acted as the protective parent of the two autonomous regions.

With independence, Zviad Gamsakhurdia became the first president. After a coup d'état and a brief civil war, Eduard Shevardnadze, a Georgian politician who in Moscow had worked closely with Gorbachev in articulating perestroika, came to power. Under Shevardnadze's presidency, between 1995 and 2003, ethnic wars broke out in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Around ten thousand people lost their lives and thousands of families fled their homes.

In 2003 the Rose Revolution against misrule, poverty, corruption and electoral fraud facilitated the restoration of territorial integrity, the return of refugees and ethnic acceptance. However, the democratic and economic reforms that followed remained a dream.

One of the leaders of the Rose Revolution, the lawyer Mikhail Saakashvili, became president a year later, declaring Georgian territorial integrity and initiating a new policy: friendship with NATO and the European Union. This rapprochement with the West, and especially the United States, put Moscow on notice .

Georgia's strategic importance stems from its geographic centrality in the Caucasus, as it is in the middle of the route of new oil and gas pipelines. European energy security underpinned the EU's interest in a Georgia that was not subservient to the Kremlin. Saakashvili made nods to the EU and also to NATO, increasing the issue of military troops and expense in armaments, something that did him no harm in 2008.

Saakashvili was successful with his policies in Ayaria, but not in South Ossetia. Continued tension in South Ossetia and various internal disputes led to political instability, which prompted Saakashvili to leave Withdrawal .

At the end of Saakashvili's term in 2013, commentator and politician Giorgi Margvelashvili took over the presidency as head of the Georgian Dream list. Margvelashvili maintained the line of rapprochement with the West, as has the current president, Salome Zurabishvili, a French-born politician, also from Georgian Dream, since 2018.

Fight for South Ossetia

The 2008 war was initiated by Georgia. Russia also contributed to previous bad relations by embargoing imports of Georgian wine, repatriating undocumented Georgian immigrants and even banning flights between the two countries. In the conflict, which affected South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Saakashvili had a modernised and prepared army, as well as full support from Washington.

The battles began in the main South Ossetian city of Tskhinval, whose population is mostly ethnic Russian. Air and ground bombardments by the Georgian army were followed by Russian tanks on the territory of entrance . Moscow gained control of the province and expelled the Georgian forces. After five days, the war ended with a death toll of between eight hundred and two thousand, depending on the different estimates of each side, and multiple violations of the laws of war. In addition, numerous reports commissioned by the EU showed that South Ossetian forces "deliberately and systematically destroyed ethnic Georgian villages". These reports also stated that it was Georgia that initiated the conflict, although the Russian side had engaged in multiple provocations and also overreacted.

Following the 12 August ceasefire, diplomatic relations between Georgia and Russia were suspended. Moscow withdrew its troops from part of the Georgian territory it had occupied, but remained in the separatist regions. Since then, Russia has recognised South Ossetia as an independent territory, as do Russian allies such as Venezuela and Nicaragua. The Ossetians themselves do not acknowledge cultural and historical ties with Georgia, but with North Ossetia, i.e. Russia. For its part, Georgia insists that South Ossetia is within its borders, and the government itself will take care of it as a matter of law and order, thus solving a problem described as constitutional.

Given Georgia's rapprochement with the EU, the conflict prompted European diplomacy to play an active role in the search for peace, with the deployment of 200 observers on the border between South Ossetia and the rest of Georgia, replacing Russian peacekeepers. In reality, the EU could have tried earlier to react more forcefully to Russia's actions in South Ossetia, which some observers believe would have prevented what happened later in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. In any case, despite initiating the conflict, this did not affect Tbilisi's relationship with Brussels, and in 2014 Georgia and the EU signed a agreement of association. Today it is safe to say that the West has forgiven Russia for its behaviour in Georgia.

The war, although short, had a clear negative impact on the Ossetian region's Economics , which in the midst of difficulties became dependent on Moscow. However, Russian financial aid does not reach the population due to the high level of corruption.

The war is over, but not the friction. In addition to a refugee problem, there is also a security problem, with Georgians being killed on the border with South Ossetia. The issue is not closed, but even if the risk is slight, everything remains in the hands of Russia, which in addition to controlling and influencing politics, runs tourism in the area.

This non-resolution of the conflict hampers the stabilisation of democracy in Georgia and with it the possible entrance accession to the European institution, as ethnic minorities claim a lack of respect for and protection of their rights. Although governance mechanisms remain weak in these conflicts, it is clear that recent reforms in the South Caucasus have led to promote inclusive dialogue with minorities and greater state accountability.

Latest elections

November 2018 saw the last direct presidential elections in the country, as from 2024 it will no longer be citizens who vote for their president, but legislators and certain compromisers, due to a constitutional reform that transforms the country into a parliamentary republic.

In 2018, candidate of the United National Movement, Grigol Vashdze, and the Georgian Dream candidate, Salome Zurabishvili, faced each other in the second round. With 60% of the vote, the centre-left candidate became the first woman president of Georgia. She won on a European platform: "more Europe in Georgia and Georgia in the European Union". Her inauguration was greeted by protesters alleging election irregularities. The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) endorsed the election process, but noted a lack of objectivity in the public media during the campaign.

Some Georgian media consider that Georgian Dream enjoyed an 'undue advantage' because of the intervention in the campaign of former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili, now a wealthy financier, who publicly announced a financial aid programme for 600,000 Georgians. It became clear that Ivanishvili pulls the strings and levers of power in the country. This questioning of the cleanliness of the campaign has led to Georgia's downgrading of democratic quality in the 2018 ratings.

![Public event presided over in January by Salome Zurabishvili at the Georgian presidential palace [Presidency of Georgia]. Public event presided over in January by Salome Zurabishvili at the Georgian presidential palace [Presidency of Georgia].](/documents/10174/16849987/georgia-blog-3.jpg)

Public event presided over in January by Salome Zurabishvili at the Georgian presidential palace [Presidency of Georgia].

THE APPROACH TO THE WEST

Since the policies pursued by the Georgian presidency since Saakashvili came to power, Georgia has made a determined move into the Western world. Thanks to all the new measures that Tbilisi is implementing to conform to Western demands and requirements , Georgia has managed to profile itself as the ideal candidate for its entrance in the EU. However, despite the pro-European and Atlanticist yearnings of the ruling Georgian Dream party and a large part of Georgian society, the country could end up surrendering to Russian pressure, as has happened with several former Soviet territories that had previously attempted a Western rapprochement, such as Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan.

EU compliance

Becoming the most favoured country in the Caucasus to join the European Union, with which it has a close and positive relationship, Georgia has signed several binding treaties with Brussels, following the aspiration of Georgian citizens for more democracy and human rights. In 2016 the agreement of association entered into force between the EU and Georgia, allowing for serious steps in political and economic integration, such as the creation of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA). This preferential trade regime makes the EU the country's main trading partner partner . The DCFTA financial aid encourages Georgia to reform its trade framework , following the principles of the World Trade Organisation, while eliminating tariffs and facilitating broad and mutual access. This alignment with the EU's framework legal framework prepares the country for eventual accession.

As for agreement of association, it should be mentioned that Georgia is a member country of the association Eastern under the European Neighbourhood Policy. Through this association, Brussels issues annual reports on the steps taken by a given state towards closer alignment with the EU. The committee of association is the formal institution dedicated to monitoring these partnership relations; its meetings have highlighted the progress made and the growing closeness between Georgia and the EU.

In 2016 the EU's Permanent Representatives committee confirmed the European Parliament's agreement on visa liberalisation with Georgia. This agreement was based on visa-free travel for EU citizens crossing the country's borders, and for Georgian citizens travelling to the EU for stays of up to 90 days.

Georgia, however, has been disappointed in its expectations when the EU has expressed doubts about the desirability of membership. Some EU member states cited the potential danger posed by Georgian criminal groups, which several pro-Russian parties in the country took advantage of to wage a vigorous campaign against the EU and NATO. The campaign paid off and anti-Russian opinion waned, prompting Moscow to assert itself further with military manoeuvres, although public support for the Georgian Dream continued in the 2016 elections.

Despite the lack of any prospect of forthcoming accession, the EU continues to offer hope, as in German Chancellor Angela Merkel's tour of the Caucasus last summer. On her visit to Georgia, Merkel compared the Georgian conflict to the Ukrainian conflict due to the presence of Russian troops in the country's separatist regions. She visited the town of Odzisi, located on the border with South Ossetia, and at a speech at the University of Tbilisi said that both that territory and Abkhazia are "occupied territories", which did not go down well with Moscow. Merkel pledged to do her utmost to ensure that this "injustice" remains present on the international diary .

Georgian President Salome Zourachvili also believes that the UK's exit from the EU could be a great opportunity for Georgia. "It will force Europe to reform. And being an optimist, I am sure it will open new doors for us," she said.

Hope in the Atlantic Alliance

Russia's behaviour in recent years, in addition to encouraging Georgia's rapprochement with the EU, has given a sense of urgency to its desire to join the Atlantic Alliance.

In 2016, several joint NATO-Georgia manoeuvres took place in the Black Sea, where a coalition fleet was stationed. This was evidence of a growing mutual rapprochement that Georgia hoped would lead to NATO membership at that year's NATO summit in Warsaw. But despite the country's extensive defence, security and intelligence training, it was not invited to join the club: Russia was not to be inconvenienced.

NATO assured, however, that it would maintain its open-door policy towards eastern countries and considered Georgia to remain an exemplary candidate . Pending future decisions, Tbilisi was left with strengthening military cooperation, offering as an incentive the "Black Sea format", a compromise solution that includes NATO, Georgia and Ukraine and increases NATO's influence in the Black Sea region.

Georgia, as the capital ally of NATO and the European Union in the Caucasus region, aspires to greater protection from the Atlantic Alliance vis-à-vis Russia. The European political centre observes the Georgian population's efforts to join the international organisation and opts for a strategy of patience for the Caucasus region, as in the Cold War years.

Approaching Russia's borders is problematic, and multiple criticisms have been levelled at NATO over the easy Georgian membership due to its geostrategic status . Russia has repeatedly expressed concern about such joint cooperation between the US, NATO and neighbouring Georgia.

![President Zurabishvili's speech at the Holocaust remembrance events in Jerusalem in January [Presidency of Georgia]. President Zurabishvili's speech at the Holocaust remembrance events in Jerusalem in January [Presidency of Georgia].](/documents/10174/16849987/georgia-blog-2.jpg)

President Zurabishvili's speech at the Holocaust remembrance events in Jerusalem in January [Presidency of Georgia].

A VIGILANT RUSSIA

The wounds of the 2008 South Ossetia war have not yet healed in Georgian society. Despite Georgia's political attempts at rapprochement with Western institutions, Russia remains suspiciously vigilant, so that relations between the two countries continue to be troubled. Last summer saw the latest episode of tension, which led the Georgian president to describe Russia as an "enemy and occupier".

After some rapprochement in 2013 that saw an increase in food trade and Russian tourism coming to the country, Moscow has shifted to a strategy of attempting rapprochement at the religious and political level. With that intention, a small group of Russian lawmakers travelled to the Georgian capital for the Orthodox Interparliamentary Assembly. This international organisation, led by Greece and Russia, is the only one that brings together the legislative bodies of Orthodox countries. The meeting took place in the plenary hall of the Georgian Parliament, where Russian MP Sergei Gabrilov took the seat of the Speaker of the House. Several politicians from the civil service examination did not take kindly to this and mobilised thousands of citizens, who staged serious public disorder in an attempted storming of the Parliament. The Russian delegation was forced to leave the country, but the attempt at Russian influence through religion was clear, whereas until then the Church had kept out of all political controversies.

The riots, in which many people were injured, prompted members of the government to cancel all foreign travel and the president to cut short her trip to Belarus, where she was to attend attend the opening of the European Games, a presence considered important in Western eyes. Demonstrators protested against the Georgian Dream headquarters, where they burned and stormed outbuildings. The ten days of rioting were not only justified by the incident at the Assembly, but also as a reaction to the Russian occupation. In addition, the conflict between the Georgian Dream and the opposing parties led by Saakashvili, now in exile in Ukraine, may also have contributed.

The crisis ended with the departure of Prime Minister Mamuka and the appointment of Georgi Gaharia as his successor, despite criticism that he had been criticised for his management of the unrest as interior minister.

The uprisings, while well-intentioned, are against Georgia's interests, the Georgian president said, as what the country needs is "internal calm and stability", both to progress internally and to gain sympathy among EU members, who do not want more tension in the region. Salome Zurabishvili warned of the risks of any internal destabilisation that Russia could provoke.

In the wake of the June protests, the Kremlin issued a decree banning the transport of nationals to Georgia by Russian airlines. While claiming to ensure "national security and protection of citizens", it was clear that Moscow was reacting to an anti-Russian tinged revolt. The decision reduced visitor arrivals from Russia, which had been accounting for one in four tourists, which the government said could mean a loss of $1 billion and a 1 per cent reduction in GDP.

The tension reached the television media in the Georgian capital. Days after the riots, the host of Rustavi 2's 'Post Scriptum' programme intervened in the broadcast speaking Russian and hurled several insults at President Vladimir Putin, which Russia described as unacceptable and 'Russophobic'. The channel apologised, admitting that its ethical and editorial standards had been violated, while several Georgian politicians, including the president, condemned the episode and lamented that such acts only increase tensions between the two nations.

The events of last summer show Georgians' rejection of an enmity with Russia that, in addition to heightening tensions with the big northern neighbour, may have an impact on Georgia's relationship with the EU and other Western international organisations, as they will not tread on quicksand, especially with big Russia in front of them.

REFERENCES

Asmus, Ronald D. A Little War That Shook the World. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010.

Cornell S. E. & Starr, F. The Guns of August 2008. Russia's War in Georgia. London: M.E. Sharpe, 2009.

De la Parte, Francisco P. The Returning Empire. La Guerra de Ucrania 2014-2017: Origen, development, entorno internacional y consecuencias. Oviedo: Ediciones de la Universidad de Oviedo, 2017.

Golz, Thomas. Georgia Diary: A Chronicle of War and Political Chaos in The Post-Soviet Caucasus.New York: Taylor and Francis, 2006.

[Glen E. Howard and Matthew Czekaj (Editors), Russia's military strategy and doctrine. The Jamestown Foundation. Washington DC, 2019. 444 pages]

REVIEW / Angel Martos Sáez

|

This exemplar acts as an answer and a guide for Western policymakers to the quandary that 21st century Russia is posing in the international arena. Western leaders, after the annexation of Crimea in February-March 2014 and the subsequent invasion of Eastern Ukraine, are struggling to come up with a definition of the aggressive strategy that Vladimir Putin's Russia is carrying out. Non-linear warfare, limited war, or "hybrid warfare" are some of the terms coined to give a name to Russia's operations below the threshold of war.

The work is divided in three sections. The first one focuses on the "geographic vectors of Russia's strategy". The authors here study the six main geographical areas in which a clear pattern has been recognized along Russia's operations: The Middle East, the Black Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, the Arctic, the Far East and the Baltic Sea.

The chapter studying Russia's strategy towards the Middle East is heavily focused on the Syrian Civil War. Russian post-USSR foreign-policymakers have realized how precious political stability in the Levant is for safeguarding their geostrategic interests. Access to warm waters of the Mediterranean or Black Sea through the Turkish straits are of key relevance, as well as securing the Tartus naval base, although to a lesser extent. A brilliant Russian military analyst, Pavel Felgenhauer, famous for his predictions about how Russia would go to war against Georgia for Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008, takes us deep into the gist of Putin's will to keep good relations with Bashar al-Assad's regime. Fighting at the same time Islamic terrorism and other Western-supported insurgent militias.

The Black and Mediterranean Seas areas are covered by a retired admiral of the Ukrainian Navy, Ihor Kabanenko. These two regions are merged together in one chapter because gaining access to the Ocean through warm waters is the priority for Russian leaders, be it through their "internal lake" as they like to call the Black Sea, or the Mediterranean alone. The author focuses heavily on the planning that the Federation has followed, starting with the occupation of Crimea to the utilization of area denial weaponry (A2/AD) to restrict access to the areas.

The third chapter concerning the Russia's guideline followed in the Arctic and the Far East is far more pessimistic than the formers. Pavel K. Baev stresses the crucial mistakes that the country has done in militarizing the Northern Sea Route region to monopolize the natural resource exploitation. This tool, however, has worked as a boomerang making it harder for Russia nowadays to make profit around this area. Regarding the Far East and its main threats (North Korea and China), Russia was expected a more mature stance towards these nuclear powers, other than trying to align its interests to theirs and loosing several opportunities of taking economic advantage of their projects.

Swedish defense ministry advisor Jörgen Elfving points out that the BSR (acronym for Baltic Sea Region) is of crucial relevance for Russia. The Federation's strategy is mainly based on the prevention, through all the means possible, of Sweden and Finland joining the North Atlantic Alliance (NATO). Putin has stressed out several times his mistrust on this organization, stating that Western policymakers haven't kept the promise of not extending the Alliance further Eastwards than the former German Democratic Republic's Western border. Although Russia has the military capabilities, another de facto invasion is not likely to be seen in the BSR, not even in the Baltic republics. Instead, public diplomacy campaigns towards shifting foreign public perception of Russia, the funding of Eurosceptic political parties, and most importantly taking advantage of the commercial ties (oil and natural gas) between Scandinavian countries, the Baltic republics and Russia is far more likely (and already happening).

The second section of this book continues with the task of defining precisely and enumerating the non-conventional elements that are used to carry out the strategy and doctrine followed by Russia. Jānis Bērziņš gives body to the "New Generation Warfare" doctrine, according to him a more exact term than "hybrid" warfare. The author stresses out the conscience that Russian leaders have of being the "weak party" in their war with NATO, and how they therefore work on aligning "the minds of the peoples" (the public opinion) to their goals in order to overcome the handicap they have. An "asymmetric warfare" under the threshold of total war is always preferred by them.

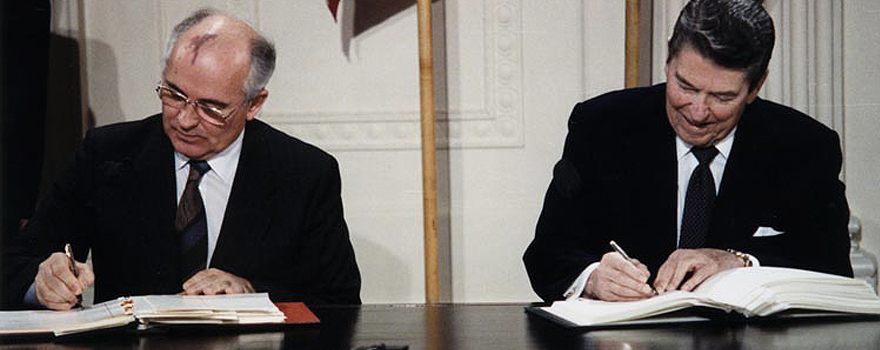

Chapters six and seven go deep into the nuclear weaponry that Russia might possess, its history, and how it shapes the country's policy, strategy, and doctrine. There is a reference to the turbulent years in which Gorbachev and Reagan signed several Non-Proliferation Treaties to avoid total destruction, influenced by the MAD doctrine of the time. It also studies the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (IMF) Treaty and how current leaders of both countries (Presidents Trump and Putin) are withdrawing from the treaty amid non-compliance of one another. Event that has sparked past strategic tensions between the two powers.

Russian researcher Sergey Sukhankin gives us an insight on the Federation's use of information security, tracing the current customs and methods back to the Soviet times, since according to him not much has changed in Russian practices. Using data in an unscrupulously malevolent way doesn't suppose a problem for Russian current policymakers, he says. So much so that it is usually hard for "the West" to predict what Russia is going to do next, or what cyberattack it is going to perpetrate.

To conclude, the third section covers the lessons learned and the domestic implications that have followed Russia's adventures in foreign conflicts, such as the one in Ukraine (mainly in Donbas) and in Syria. The involvement in each one is different since the parties which the Kremlin supported are opposed in essence: Moscow fought for subversion in Eastern Ukraine but for governmental stability in Syria. Russian military expert Roger N. McDermott and analyst Dima Adamsky give us a brief synthesis of what experiences Russian policymakers have gained after these events in Chapters nine and eleven.

The last chapter wraps up all the research talking about the concept of mass mobilization and how it has returned to the Federation's politics, both domestically and in the foreign arena. Although we don't exactly know if the majority of the national people supports this stance, it is clear that this country is showing the world that it is ready for war in this 21st century. And this guide is here to be a reference for US and NATO defense strategists, to help overcome the military and security challenges that the Russian Federation is posing to the international community.

Thierry Baudet's electoral surprise and the new Dutch right wing

The Netherlands has seen in recent years not only the decline of some of the traditional parties, but even the new party of the populist Geert Wilders has been overtaken by an even newer training , led by Thierry Baudet, also markedly right-wing but somewhat more sophisticated. The political earthquake of the March regional elections could sweep away the coalition government of the liberal Mark Rutte, who has provided continuity in Dutch politics over the past nine years.

▲ Thierry Baudet, in an advertising spot for his party, Forum for Democracy (FVD).

article / Jokin de Carlos Sola

On March 20, regional elections were held in the Netherlands. The parties that make up the coalition that keeps Mark Rutte in power suffered a strong punishment in all regions, and the same happened with the party of the famous and controversial Geert Wilders. The big winner of these elections was the Forum for Democracy (FvD) party, founded and led by Thierry Baudet, 36, the new star of Dutch politics. These results sow doubts about the future of Mark Rutte's government once the composition of the Senate is renewed next May.

Since World War II, three forces have been at the center of Dutch politics: the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), the Labor Party (PvA) and the liberal People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD). All three accounted for 83% of the Dutch electorate in 1982. Due to the Dutch system of proportional representation, no party has ever had an absolute majority, so there have always been coalition governments. The system also means that, because they are not punished, small parties always achieve representation, thus providing a great ideological variety in Parliament.

Over the years, the three main parties lost influence. In 2010, after eight years in government, the CDA went from 26% and first place in Parliament to 13% and fourth place. This fall brought the VVD to power for the first time under the leadership of Mark Rutte and triggered the entrance of Geert Wilders and his Party for Freedom (PVV), a right-wing populist training , in Dutch politics. Shortly thereafter Rutte formed a Grand Coalition with the PvA. However, this decision caused Labour to drop from 24% to 5% in the 2017 elections. These results meant that both the VVD and Rutte were left as the last element of old Dutch politics.

These 2017 elections generated even greater diversity in Parliament. In them, parties such as the Reformed Party, of Calvinist Orthodox ideology; the baptized 50+, with the goal to defend the interests of retirees, or the DENK party, created to defend the interests of the Turkish minority in the country, achieved representation. However, none of these parties would later be as relevant as the Forum for Democracy and its leader Thierry Baudet.

Forum for Democracy

The Forum for Democracy was founded as a think tank in 2016, led by 33-year-old French-Dutchman Thierry Baudet. The following year the FvD became a party, presenting itself as a conservative or national conservativetraining , and won two MPs in regional elections. Since then it has been growing, mainly at the expense of Geert Wilders and his PVV. One of the main reasons for this is that Wilders is accused of having no program other than the rejection of immigration and the exit from the European Union. As celebrated as it was controversial was the fact that PVV presented its program on only one page. On the contrary, Baudet has created a broad program in which issues such as the introduction of direct democracy, the privatization of certain sectors, the end of military cuts and a rejection of multiculturalism in general are proposed. On the other hand, Baudet has created an image of greater intellectual stature and respectability than Wilders. However, the party has also suffered declines in popularity because of certain attitudes of Baudet, such as his climate change denialism, his relationship with Jean Marie Le Pen or Filip Dewinter, and his refusal to answer whether he linked IQ to race.

Regional Elections

The Netherlands is divided into 12 regions, each region has a committee, which can have between 39 and 55 representatives. Each committee elects both the Royal Commissioner, who acts as the highest authority in the region, and the executive, usually formed through a coalition of parties. The regions have a number of powers granted to them by the central government.

In the provincial elections last March, the FvD became the leading party in 6 out of 12 regions, including North Holland and South Holland, where the cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague, which had been traditional VVD strongholds, are located. In addition to this, it became the party with the most representatives in the whole of the Netherlands. These gains were achieved mainly at the expense of the PVV. Although these results do not guarantee the FvD government in any region, they do give it influence and media coverage, something Baudet has been able to take advantage of.

Several media linked Baudet's victory to the murder a few days earlier in Utrecht of three Dutch nationals by a Turkish citizen, which authorities said was most likely terrorist motivated. However, the FvD had been growing and gaining ground for some time. The reasons for its rise are several: the decline of Wilders, the actions of Prime Minister Rutte in favor of Dutch companies such as Shell or Unilever (business where he previously worked), the erosion of the traditional parties, which in turn damages their allies, and the rejection of certain immigration policies that Baudet linked to the attack in Utrecht. The Dutch Greens have also experienced great growth, accumulating the young vote that previously supported Democrats 66.

|

result of the Dutch regional elections on March 20, 2019 [Wikipedia]. |

Impact on Dutch Policy

The victory of the Baudet party over Rutte's party directly affects the central government, the Dutch electoral system and the prime minister himself. First of all, many media welcomed the results as a evaluation of the Dutch people on Rutte's government. The biggest punishment was for Rutte's allies, the Democrats 66 and the Christian Democratic Appeal, which lost the most support in the regions. Since coming to power in 2010, Rutte has managed to maintain the loyalty of his electorate, but all his allies have ended up being punished by their voters. Therefore, it is possible that Rutte's government will not be able to finish its mandate, if his allies end up turning their backs on him.

The result of the March regionals may have a second impact on the Senate. The Dutch do not appoint their senators directly, but the regional councils elect the senators, so the results of the regional elections have a direct effect on the composition of the upper house. It is therefore very likely that the parties that make up Rutte's government will suffer a major setback in the Senate, which will make it difficult for the Prime Minister to pass his legislative initiatives.

The third consequence directly affects Rutte himself. In 2019 Donald Tusk finishes his second term as president of the European committee and Rutte had a good chance of succeeding him, but with him being the main electoral asset of his party, his departure could sink the VVD. It could then happen as it did with Tusk's departure from Poland, which resulted in a conservative victory a year later.

Whatever the outcome, Dutch politics has in recent years shown great volatility and a lot of movement. In 2016 it was believed that Wilders would win the election and previously that D66 would wrest the Liberal leadership from the VVD. It is difficult to predict which way the wind will turn the mill.

[Francisco Pascual de la Parte, The returning empire. The Ukrainian War 2014-2017: Origin, development, international environment and consequences. Editions of the University of Oviedo. Oviedo, 2017. 470 pages]

review / Vitaliy Stepanyuk[English version].

|

In this research on the Ukrainian war and the Russian intervention in the confrontation, the author analyzes the conflict focusing on its precedents and the international context in which it develops. For that purpose, he also analyzes with special emphasis Russia's relations with other states, particularly since the fall of the USSR. Above all, this study covers Russia's interaction with the United States, the European Union, the neighboring countries that emerged from the disintegration of the USSR (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania...), the Caucasus, the Central Asian republics (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan...), China and Russia's involvement in the Middle East conflict. All these relations have, in some way, repercussions on the Ukrainian conflict or are a consequence of it.

The book is structured, as the author himself explains in its first pages, in such a way that it allows for different ways of reading it. For those who wish to have a general knowledge of the Ukrainian question, they can read only the beginning of the book, which gives a brief description of the conflict from its two national perspectives. Those who also want to understand the historical background that led to the confrontation can also read the introduction. The second chapter explains the origin of Russian suspicion towards liberal ideas and the Western inability to understand Russian concerns and social changes. Those who wish to assimilate the conflict in all its details and understand its political, strategic, legal, economic, military and cultural consequences should read the rest of the book. Finally, those who just want to understand the possible solutions to the dispute can skip directly to the last two chapters. In the final pages, readers can also find an extensive bibliography used to write this volume and some appendices with documents, texts and maps relevant to the study of the conflict.

The Ukraine problem began in late 2013 with the protests at the place Maidan in Kiev. Almost six years later, the conflict seems to have lost international interest, but the truth is that the war continues and its end is not yet in sight. When it started, it was a shock no one expected. Hundreds of people took to the streets demanding better living conditions and an end to corruption. The international media made extensive coverage of what was happening, and everyone was aware of the news about Ukraine. Initially held peacefully, the protests turned violent due to repression by government forces. The president fled the country and a new, pro-European oriented government was established and accepted by the majority of citizens. However, this achievement was met by Russian intervention in Ukrainian territory, which resulted in the illegal annexation of the Crimean peninsula, in an action that Russia justified on the grounds that they were only protecting the Russian population living there. In addition, an armed conflict began in the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine between Ukrainian troops and a Russian-backed separatist movement.

This is just a brief summary of how the conflict originated, but certainly things are more complex. According to the book, the Ukrainian war is not an isolated conflict that happened unexpectedly. In fact, the author argues that Russia's reaction was quite presumable in those years, due to the internal and external conditions in the country, generated by Putin's attitude and by the Russian mentality. The author lists warnings of what could happen in Ukraine and nobody noticed: civil protests in Kazakhstan in 1986, the Nagorno Karabakh War (a region between Armenia and Azerbaijan) started in 1988, the Transnistrian war (in Moldova) started in 1990, separatist movements in Abkhazia and South Ossetia (two regions of Georgia).... Russia usually supported and helped the separatist movements, claiming in some cases that it had to protect the Russian minorities living in those places. This gave a fairly clear idea of Russia's position towards its neighbors and reflected that, despite having initially accepted the independence of these former Soviet republics after the fall of the USSR, Russia was not interested in losing its influence in these regions.

Russian instincts

An interesting idea that is sample in the book is the fact that, although the USSR collapsed and Soviet institutions disappeared, the yearning for a strong empire remained, as well as the distrust and rivalry with the Western powers. These issues shape Russia's domestic and foreign policy, especially defining the Kremlin's relations with the other powers. The essence of the USSR persisted under another banner, because the Soviet elites remained undisturbed. One might think that the survival of these Soviet inertias is due to the ineffective reform process sustained by the Western liberal powers in the USSR after its collapse. But it should be noted that the sudden incursion of Western customs and ideas into a Russian society unprepared to assimilate them, without a strategy aimed at facilitating such change, had a negative impact on the Russian people. By the end of the 1990s, most Russians thought that the introduction of so-called "democratic reforms" and the free market, with its unexpected results of massive corruption and social deterioration, had been a big mistake.

In that sense, Putin's arrival meant the establishment of order in a chaotic society, although it meant the end of democratic reforms. Moreover, the people of Russia saw in Putin a leader capable of standing up to the Western powers (unlike Yeltsin, the previous Russian president, who had had a weak position towards them) and bringing Russia to the place it should occupy: Russia as a great empire.

One of the main consequences of the Ukrainian conflict is that the context of relations between Russia and the Western powers has frozen dramatically. Although their relations were bad after the collapse of the USSR, those relations deteriorated much further due to the annexation of Crimea and the war in Ukraine.

The Kremlin adopted suspicion, especially of the West, as a basic principle. At the same time, Russia fostered cooperation with China, Egypt, Syria, Venezuela, Iran, India, Brazil and South Africa as a means of confronting NATO, the EU and the United States. On the one hand, President Putin wanted to reduce the weight of Western powers in the international economic sphere; on the other hand, Russia also began to develop stronger relations with alternative countries in order to confront the economic sanctions imposed by the European Union. Due to these two reasons, Russia created the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), formed in May 2014, with the goal to build economic integration on the basis of a customs union. Today, the EAEU consists of five members: Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia.

In addition, Russia has been extremely vocal in denouncing NATO's expansion into Eastern European countries. The Kremlin has used this topic as an excuse to strengthen its army and establish new alliances. Together with some allies, Russia has organized massive military trainings near the borders of Poland and the Balkan countries. It is also working to create disputes among NATO members and weaken the organization.

In particular, the Ukrainian conflict has also shown the differences between Russian determination and Western indecisiveness, meaning that Russia has been able to carry out violent and illegal measures without being met with solid and concrete solutions from the West. Arguably, Russia uses, above all, hard power, taking advantage of economic (the sale of oil and gas, for example) and military means to dictate the actions of another nation through coercion. Its use of soft power occupies, in some ways, a subordinate place.

According to some analysts, Russia's hybrid war against the West includes not only troops, weapons and computers (hackers), but also the creation of "frozen conflicts" (e.g., the Syrian war) that has established Russia as an indispensable party in conflict resolution, and the use of propaganda, the media and its intelligence services. In addition, the Kremlin was also involved in the financing of pro-Russian political parties in other countries.

Russian activity is incomprehensible if we do not take into consideration the strong and powerful propaganda (even more powerful than the propaganda system of the USSR) used by the Russian authorities to justify the behavior of the Government towards its own citizens and towards the international community. One of the most commonly used arguments is to blame the United States for all the conflicts that are occurring in the world and to justify Russia's actions as a reaction to an aggressive American position. According to the Russian media, the goal allegedly main U.S. goal is to oppress Russia and foment global disorder. In that sense, the general Russian tendency is to replace liberal democracy with the national idea, with great patriotic exaltations to create a sense of unity, against a definite adversary, the states with liberal democracies and the International Organizations.

Another interesting topic is the author's explanation of how different Russia's view of the world, security, relations between nations or the rule of law is compared to Western conceptions. While the West focuses on defense and enforcement of international law, Russia claims that each country is manager of its own security and takes all necessary measures in this regard (even if it contradicts international law or any international treaty or agreement ). Definitely, what we see today is a New Cold War consisting of a bloc of liberal-democratic states, tending towards the achievement of extensive globalized trade and finance, against another bloc of major totalitarian and capitalist-authoritarian regimes, with a clear tendency towards militarization.

Successes and outlook

The book offers a deep and broad view of what Russian foreign policy is today. It highlights the idea that the Ukrainian conflict is not an isolated dispute, but a conflict that is embedded in a much more complex network of circumstances. He makes it clear that the International Office does not function as a structured and patterned mechanism, but as a field where countries have different views on how the world is governed and what its rules should be. We could say that there is a struggle between a liberal vision supported by the West, which emphasizes international cooperation and the rejection of power as the only way to act in the international sphere, and a realist vision, defended by Russia, which explains foreign affairs in terms of power, state centralism and anarchy.

One of the strengths of the book is that sample presents the different positions of many different analysts, with criticisms of both Russian and Western activities. This allows the reader to examine the conflict from different perspectives and to acquire a comprehensive and critical view of topic. In addition, the text financial aid to learn and understand the real state of affairs in other countries of Eastern Europe, Central Asia and the Caucasus, regions little known in Western society.

This is an excellent work from research, which allows to examine the complicated reality surrounding the war in Ukraine and to deepen the study of relations between nations.

Ukrainian Orthodox break with Russia shifts tension between Kiev and Moscow to the religious sphere

While Russia closed the Sea of Azov approaches to Ukraine, at the end of 2018, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church advanced its independence from the Moscow Patriarchate, cutting off an important element of Russian influence on Ukrainian society. In the "hybrid war" posed by Vladimir Putin, with its episodes of counter-offensives, religion is one more sphere of underhand pugnacity.

![Proclamation of autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, with attendance by Ukrainian President Poroshenko [Mykola Lazarenko]. Proclamation of autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, with attendance by Ukrainian President Poroshenko [Mykola Lazarenko].](/documents/10174/16849987/iglesia-ortodoxa-blog.jpg)

▲ Proclamation of autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, with attendance of Ukrainian President Poroshenko [Mykola Lazarenko].

article / Paula Ulibarrena

January 5, 2019 was an important day for the Orthodox Church. In historic Constantinople, today Istanbul, in the Orthodox Cathedral of St. George, the ecclesiastical rupture between the Kievan Rus and Moscow was verified, thus giving birth to the fifteenth autocephalous Orthodox Church, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew I, presided over the ceremony together with the Metropolitan of Kiev, Epiphanius, who was elected last fall by the Ukrainian bishops who wanted to split from the Moscow Patriarchate. After a solemn choral welcome for the 39-year-old Epiphanius, the church leaders placed on a table in the church the tomos (decree), a parchment written in Greek certifying the independence of the Ukrainian Church.

But the one who actually led the Ukrainian delegation was the president of that republic, Petro Poroshenko. "It is a historic event and a great day because we were able to hear a prayer in Ukrainian in St. George's Cathedral," Poroshenko wrote moments later on his account on the social network Twitter.

The event was strongly opposed by the Moscow Patriarchate, which has long been at odds with the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Archbishop Ilarion, head of external relations of the Russian Orthodox Church, compared status to the East-West Schism of 1054 and warned that the current conflict could last "for decades and even centuries".

The great schism

This is the name given to the schism or separation of the Eastern (Orthodox) Church from the Catholic Church of Rome. The separation developed over centuries of disagreements beginning with the moment in which the emperor Theodosius the Great divided the Roman Empire into two parts between his sons, Honorius and Arcadius, upon his death (year 395). However, the actual split did not take place until 1054. The causes are ethnic subject due to differences between Latins and Easterners, political due to the support of Rome to Charlemagne and of the Eastern Church to the emperors of Constantinople but above all due to the religious differences that throughout those years were distancing both churches, both in aspects such as sanctuaries, differences of worship, and above all due to the pretension of both ecclesiastical seats to be the head of Christendom.

When Constantine the Great moved the capital of the empire from Rome to Constantinople, it became known as New Rome. After the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire to the Turks in 1453 Moscow used the name "Third Rome". The roots of this sentiment began to develop during the reign of the Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan III, who had married Sophia Paleologos who was the niece of the last ruler of Byzantium, so that Ivan could claim to be the heir of the collapsed Byzantine Empire.

The different Orthodox churches

The Orthodox Church does not have a hierarchical unity, but is made up of 15 autocephalous churches that recognize only the power of their own hierarchical authority, but maintain doctrinal and sacramental communion among themselves. This hierarchical authority is usually equated to the geographical delimitation of political power, so that the different Orthodox churches have been structured around the states or countries that have been configured throughout history, in the area that emerged from the Eastern Roman Empire, and later occupied the Ottoman Empire.

They are the following churches: Constantinople, the Russian (which is the largest, with 140 million faithful), Serbian, Romanian, Bulgarian, Cypriot, Georgian, Polish, Czech and Slovak, Albanian and American Orthodox, as well as the very prestigious but small churches of Alexandria, Jerusalem and Antioch (for Syria).

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church has historically depended on the Russian Orthodox Church, parallel to the country's dependence on Russia. In 1991, following the fall of communism and the disappearance of the USSR, many Ukrainian bishops self-proclaimed the Kiev Patriarchate and separated from the Russian Orthodox Church. This separation was schismatic and did not gain support from the rest of the Orthodox churches and patriarchates, and in fact meant that two Orthodox churches coexisted in Ukraine: the Kiev Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Church dependent on the Moscow Patriarchate.

However this lack of initial supports changed last year. On July 2, 2018, Bartholomew, Patriarch of Constantinople, declared that there is no canonical territory of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine as Moscow annexed the Ukrainian Church in 1686 in a canonically unacceptable manner. On October 11, the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople decided to grant autocephaly of the Ecumenical Patriarch to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and revoked the validity of the synodal letter of 1686, which granted the right to the Patriarch of Moscow to ordain the Metropolitan of Kiev. This led to the reunification of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and its severance of relations with the Moscow Orthodox Church.

On December 15, in the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Kiev, the Extraordinary Synod of Unification of the three Ukrainian Orthodox Churches was held, with the Archbishop of Pereýaslav-Jmelnitskiy and Bila Tserkva Yepifany (Dumenko) being elected as Metropolitan of Kiev and All Ukraine. On January 5, 2019, in the Patriarchal Cathedral of St. George in Istanbul Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople Bartholomew I initialed the tomos of autocephaly of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.

Does politics accompany division or is it the cause of it?

In Eastern Europe, the intimate relationship between religion and politics is almost a tradition, as it has been since the beginnings of the Orthodox Church. It seems evident that the political confrontation between Russia and Ukraine parallels the schism between the Orthodox Churches in Moscow and Kiev, and is even a further factor adding tension to this confrontation. In fact, the political symbolism of the Constantinople event was reinforced by the fact that it was Poroshenko, and not Epiphanius, who received the tomos from the hands of the Ecumenical Patriarch, whom he thanked for the "courage to take this historic decision". Previously, the Ukrainian president had already compared this fact with the referendum by which Ukraine became independent from the USSR in 1991 and with the "aspiration to join the European Union and NATO".

Although the separation had been years in the making, interestingly, the quest for such religious independence has intensified following Russia's annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea in 2014 and Moscow's support for separatist militias in eastern Ukraine.

The first result was made public on November 3, with a visit by Poroshenko to Fanar, Bartholomew's see in Istanbul, after which the patriarch underlined his support for Ukrainian ecclesiastical autonomy.

Constantinople's recognition of an autonomous Ukrainian church is also a boost for Poroshenko, who faces a tough election degree program in March. In power since 2014, Poroshenko has focused on the religious issue much of his speech. "Army, language, faith," is his main election slogan. In fact, after the split, the ruler stated, "the Ukrainian Orthodox Church is born without Putin and without Kirill, but with God and with Ukraine."

Kiev claims that Moscow-backed Orthodox churches in Ukraine - some 12,000 parishes - are in reality a propaganda tool of the Kremlin, which also uses them to support pro-Russian rebels in the Donbas. The churches vehemently deny this.

On the other side, Vladimir Putin, who set himself up years ago as a defender of Russia as an Orthodox power and counts the Moscow Patriarch among his allies, fervently opposes the split and has warned that the division will produce "a great dispute, if not bloodshed."

Moreover, for the Moscow Patriarchate -which has been rivaling for years with Constantinople as the center of Orthodox power- it is a hard blow. The Russian Church has about 150 million Orthodox Christians under its authority, and with this separation it would lose a fifth of them, although it would still remain the most numerous Orthodox patriarchate.

This fact also has a political twin, as Russia has stated that it will break off relations with Constantinople. Vladimir Putin knows that he is losing one of the greatest sources of influence he has in Ukraine (and in what he calls "the Russian world"): that of the Orthodox Church. For Putin, Ukraine is at the center of the birth of the Russian people. This is one of the reasons, along with Ukraine's important geostrategic position and its territorial extension, why Moscow wants to continue to maintain spiritual sovereignty over the former Soviet republic, since politically Ukraine is moving closer to the West, both to the EU and to the United States.

Nor should we forget the symbolic burden. The Ukrainian capital, Kiev, was the starting point and origin of the Russian Orthodox Church, something that President Putin himself often recalls. It was there that Prince Vladimir, a medieval Slavic figure revered by both Russia and Ukraine, converted to Christianity in 988. "If the Ukrainian Church wins its autocephaly, Russia will lose control of that part of history it claims as the origin of its own," Dr. Taras Kuzio, a professor at Kiev's Mohyla Academy, tells the BBC. "It will also lose much of the historical symbols that are part of the Russian nationalism that Putin advocates, such as the Kiev Caves monastery or St. Sophia Cathedral, which will become entirely Ukrainian. It is a blow to the nationalist emblems that Putin boasts of."

Another aspect to consider is that the Orthodox churches of other countries (Serbia, Romania, Alexandria, Jerusalem, etc.) are beginning to align themselves on one side or the other of the great rift: with Moscow or with Constantinople. It is not clear if this will remain a merely religious schism, if it occurs, or if it will also drag the political power, since it should not be forgotten, as has already been pointed out, that in that area which we call the East there have always been very strong ties between religious and political power since the great schism with Rome.

|

Enthronement ceremony of the erected Patriarch of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church [Mykola Lazarenko]. |

Why now?

The advertisement of the split between the two churches is, for some, logical in historical terms. "After the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the independent Orthodox churches were configured in the 19th century from agreement to the national borders of the countries and this is the patron saint that, with delay, Ukraine is now following", explains the theologian Aristotle Papanikolaou director of the Center of programs of study Orthodox Christians of the University of Fordham, in the United States, in the above mentioned information of the BBC.

It must be seen as Constantinople's opportunity to detract power from the Moscow Church, but above all it is the reaction of general Ukrainian sentiment to Russia's attitude. "How can Ukrainians accept as spiritual guides members of a church believed to be involved in Russian imperialist aggressions?" asks Papanikolau, acknowledging the impact that the Crimean war and its subsequent annexation may have had on the attitude of Constantinople's churchmen.

There is thus a clear and parallel relationship between the deterioration of political relations between Ukraine and Russia and the separation between the Kievan Rus and the Moscow Church. Both Orthodox Churches are closely intertwined, not only in their respective societies, but also in the political spheres and these in turn use for their purposes the important ascendancy of the Churches over the inhabitants of the two countries. In final, the political tension drags or favors the ecclesiastical tension, but at the same time the aspirations of independence of the Ukrainian Church see this moment of political confrontation as the ideal moment to become independent from the Muscovite one.

[Bruno Maçães, The Dawn of Eurasia. On the Trail of the New World Order. Allen Lane. Milton Keynes, 2018. 281 pp]

review / Emili J. Blasco

|

The discussion on the emergence of Eurasia as an increasingly compact reality, no longer as a mere geographical description that was conceptually a chimera, owes much to the contribution of Bruno Maçães; particularly to his book The Dawn of Eurasia, but also to his continuous proselytizing to different audiences. This Portuguese diplomat with research activity in Europe notes the consolidation of the Eurasian mass as a single continent (or supercontinent) to all intents and purposes.