Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Security and defence .

Armenia and Azerbaijan clash in a conflict that has also involved Turkey and Russia.

![Monument to the Armenian capture of the city of Shusha in the war over Nagorno-Karabakh in the 1990s [Wikipedia]. Monument to the Armenian capture of the city of Shusha in the war over Nagorno-Karabakh in the 1990s [Wikipedia].](/documents/16800098/0/nagorno-karabaj-blog.jpg/222b236d-6a6a-e4af-fd54-efef333f0717?t=1621884636053&imagePreview=1)

Monument to the Armenian capture of the city of Shusha in the war over Nagorno-Karabakh in the 1990s [Wikipedia].

ANALYSIS / Irene Apesteguía

The region of Nagorno-Karabakh, traditionally inhabited by Christian Armenians and Muslim Turks, is internationally recognised as part of Azerbaijan. However, its population is Armenian-majority and pro-independence. In Soviet times it became an autonomous region within the Republic of Azerbaijan and it was in the war of the 1990s that, in addition to leaving some 30,000 dead and around a million people displaced, separatist forces captured additional Azeri territory. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, ethnic discrepancies between Azerbaijan and Armenia have deepened. Even a 2015 census of Nagorno-Karabakh reported that no Azeris lived there, whereas in Soviet times Azeris made up more than a fifth of the population. Since the truce between the two former Soviet republics in 1994, there has been a status stalemate, with the failure of several negotiations to reach a permanent peace agreement . The dispute has remained frozen ever since.

On 27 September, the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan once again led to a military confrontation. Recent developments go far beyond the usual clashes, with reports of helicopter shoot-downs, use of combat drones and missile attacks. In 2016 there was a violent escalation of the conflict, but Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, was not occupied and no martial law was declared. If one thing is clear, it is that the current escalation is a direct consequence of the freezing of the negotiation process. Moreover, this is the first time that armed outbreaks have occurred at such short intervals, the last escalation of the conflict having taken place last July.

Azerbaijan's Defence Minister Zakir Hasanov on 27 September threatened a "big attack" on Stepanakert if the separatists did not stop shelling its settlements. Nagorno-Karabakh declared that it would respond in a "very painful" way. Armenia, for its part, warned that the confrontation could unleash a "full-scale war in the region".

The leaders of both countries hold each other responsible for this new escalation of violence. According to Azerbaijan, the Armenian Armed Forces constantly provoked the country, firing on the army and on crowds of civilians. Moreover, on multiple local Azerbaijani television channels, President Ilham Aliyev has declared that Armenia is preparing for a new war, concentrating all its forces in Karabakh. Even the Azeri authorities have restricted internet use in the country, mainly limiting access to social media.

In its counter-offensive operation, Azerbaijan mobilised staff and tank units with the support of artillery and missile troops, front-line aviation and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), the ministry's press release statement said. Moreover, according to agreement with the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a number of Syrians from jihadist groups, from Turkish-backed factions, are fighters in Nagorno-Karabakh. This has been corroborated by Russian and French sources. In any case, it would not be surprising when Turkey sits alongside Azerbaijan.

For its part, Armenia blames Azerbaijan for starting the fighting. Armenian officials announced that the Azerbaijani army had attacked with rocket-propelled grenade launchers and missiles. Armenia has not stopped preparing, as in the weeks leading up to the start of the fighting, multiple shipments of Russian weapons had been detected in the country via heavy transport flights. On the other hand, Armenia's defence minister has accused Turkey of exercising command and control over Azerbaijan's air operations via Boeing 737 Airborne Early Warning & Control aircraft , as Turkey has four of these planes.

Triggers

Both powers were on alert because of the July fighting. Since then, they have not abandoned military preparedness at the hands of their external allies. The current events cannot therefore be described as coming out of the blue. After the July outbreak, there has been a lingering sense that the armed confrontation had simply been left at Fail.

Hours after the outbreak of fighting, Armenia declared martial law and general mobilisation. Azerbaijan, on the contrary, declared that such action was not necessary, but eventually the parliament decided to impose martial law in some regions of the country. Not only was martial law decreed, but also the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence declared the liberation of seven villages, the establishment of a curfew in several cities and the recapture of many important heights. It is clear that all occupied territories have crucial strategic value: Azerbaijan has secured visual control of the Vardenis-Aghdara road, which connects to Armenian-occupied Karabakh. The road was completed by Armenia three years ago in order to facilitate rapid military cargo transfers, an indication that this is a strategic position for Armenia.

Drone warfare has also been present in the conflict with Turkish and Israeli drones used by Azerbaijan. Armenia's anti-drone measures are bringing Iran into the picture.

An important factor that may have led to the conflict has been changes in the diplomatic leadership in Baku. Elmar Mammadyarov, Azerbaijan's foreign minister, left his position during the July clashes. He has been replaced by former Education minister Jeyhun Bayramov, who does not have much diplomatic experience. Meanwhile, Hikmet Hajiyev, the Azerbaijani president's foreign policy advisor has seen his role in these areas increase.

But the problem is not so much about new appointments. For the past few years, Mammadyarov was the biggest optimist about the concessions Armenia might be willing to make under Nikol Pashinyan's new government. Indeed, since Armenia's Velvet Revolution, which brought Pashinyan to the post of prime minister in 2018, Azerbaijan had been hopeful that the conflict could be resolved. This hope was shared by many diplomats and experts in the West. Moreover, even within Armenia, Pashinyan's opponents labelled him a traitor because, they claimed, he was selling out Armenia's interests in exchange for Western money. All this hope for Armenia disappeared, as the new Armenian prime minister's position on Nagorno-Karabakh was harsher than ever. He even declared on several occasions that "Karabakh is Armenia". All this led to a strengthening of Azerbaijan's position, which hardened after the July clashes. Baku has never ruled out the use of force to try to solve the problem of its territorial integrity.

In the 2016 conflict there were many efforts to minimise these armed disturbances, mainly by Russian diplomacy. These have been supported by the West, which saw Moscow's mediation as positive. However, negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan have not resumed, and the excuse of the coronavirus pandemic has not been very convincing, according to domestic media.

More points have led to the current escalation, such as increased Turkish involvement. After the July clashes, Turkey and Azerbaijan conducted joint military exercises. Ankara's representatives began to talk about the ineffectiveness of the peace process, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, speaking last month at the UN General Assembly, described Armenia as the biggest obstacle to long-term peace deadline in the South Caucasus. This is not to say that Turkey provoked the new escalation, but it certainly helped push Azerbaijan into a more emboldened attitude. The Turkish president stated on Twitter that 'Turkey, as always, stands with all its brothers and sisters in Azerbaijan'. Moreover, last August, Azerbaijan's defence minister said that, with the Turkish army's financial aid , Azerbaijan would fulfil 'its sacred duty', which can be interpreted as the recovery of lost territories.

International importance

In a brief overview of the allies, it is worth mentioning that the Azeris are a majority ethnic Turkic population, with whom Turkey has close ties, although unlike the Turks, most Azeris are Shia Muslims. As for Armenia, Turkey has no relations with Armenia, as the former is a largely Orthodox Christian country that has historically always relied on Russia.

As soon as the hostilities began, several states and international organisations called for a ceasefire. For example, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, in a telephone conversation with his Armenian counterpart Zohrab Mnatsakanyan, called for an end to the fighting and declared that Moscow would continue its mediation efforts. Meanwhile, as it did after the July clashes, Turkey again expressed through various channels its plenary session of the Executive Council support for Azerbaijan. Turkey's Foreign Ministry assured that Ankara is ready to help Baku in any way it can. The Armenian president, hours before the start of the fire, mentioned that a new conflict could "affect the security and stability not only of the South Caucasus, but also of Europe". US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo expressed serious concerns and called on both sides to stop the fighting.

On the other hand, there is Iran, which is mainly Shia and also has a large ethnic Azeri community in the northwest of the country. However, it has good relations with Russia. Moreover, having borders with both countries, Iran has offered to mediate peace talks. This is the focus of Iran's current problem with the new conflict. Azeri activists called for protests in Iranian Azerbaijan, which is the national territory of Azeris under Iranian sovereignty, against Tehran's support for Armenia. The arrests carried out by the Iranian government have not prevented further protests by this social sector. This response on the streets is an important indicator of the current temperature in northwest Iran.

As for Western countries, France, which has a large Armenian community, called for a ceasefire and the start of dialogue. The US said it had contacted both sides to urge them to "cease hostilities immediately and avoid words and actions of little consequence financial aid".

Russia may have serious concerns about the resumption of full-scale hostilities. It has made it clear on multiple occasions that the important thing is to prevent the conflict from escalating. One reason for this insistence may be that the Kremlin already has open fronts in Ukraine, Syria and Libya, in addition to the current status in Belarus, and the poisoning of Alexei Navalni. Moreover, despite the current attempt by the presidents of Russia and Turkey to show that relations between their countries are going well, the discrepancies between them, such as their views on Syria and Libya, are growing and becoming more diverse. And now Vladimir Putin could not leave Armenia in the hands of Azerbaijan and Turkey.

The Minskgroup of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) has as its main mission statement mediation of peace negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and is co-chaired by Russia, France and the United States. In response to the current conflict, it called for a "return to a ceasefire and resumption of substantive negotiations". Earlier this year, Armenia rejected the Madrid Principles, the main conflict resolution mechanism proposed by group in Minsk. Moreover, this initiative has been made increasingly impossible by the Armenian Defence Ministry's concept of a "new war for new territories", as well as Nikol Pashinyan's idea of Armenia-Karabakh unification. All this has infuriated the Azeri government and citizens, who have increasingly criticised the Minsk group . Azerbaijan has also criticised the group 's passivity in the face of what it sees as Armenia's inflammatory actions, such as the relocation of Karabakh's capital to Susa, a city of great cultural importance for Azerbaijanis, or the illegal settlement of Lebanese and Armenians in occupied Azerbaijani territories.

If any conclusion is to be drawn from this it is that, for many in both Azerbaijan and Armenia, the peace process has been discredited by the past three decades of failed negotiations, prompting increasing warnings that the status quo would lead to a further escalation of the conflict.

There is growing concern among some experts that Western countries do not understand the current status and the consequences that could result from the worst flare-up in the region in years. The director of the South Caucasus Office at the Heinrich Boell Foundation, Stefan Meister, has argued that the fighting between these two regions could go far. In his opinion, "the conflict is underestimated by the EU and the West".

The EU has also taken a stand. It has already order to Armenia and Azerbaijan to de-escalate cross-border tensions, urging them to stop the armed confrontation and to refrain from actions that provoke further tension, and to take steps to prevent further escalation.

The conflict in the Caucasus is of great international importance. There are regular clashes and resurgences of tensions in the area. The relevance is that any escalation of violence could destabilise the global Economics , given that the South Caucasus is a corridor for gas pipelines from the Caspian Sea to world markets, and more specifically to Europe. If Armenia decides that Azerbaijan has escalated too far, it could attack Azerbaijan's South Caucasus Pipeline, which sends gas to Turkey's TANAP, and ends with TAP, which supplies Europe. Another strategic aspect is the control of the city of Ghana'a, as controlling it could connect Russia to Karabakh. In addition, control of the site could cut off gas pipeline connectivity between Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. Conflicts already took place at area last July, which is why Azerbaijan is prepared to close the region's airspace as a result of the new conflict.

![In bright green, territory of Nagorno-Karabakh agreed in 1994; in soft green, territory controlled by Armenia until this summer [Furfur/Wikipedia]. In bright green, territory of Nagorno-Karabakh agreed in 1994; in soft green, territory controlled by Armenia until this summer [Furfur/Wikipedia].](/documents/16800098/0/nagorno-karabaj-mapa.jpg/112d46eb-041d-b714-85b0-10a262216ce3?t=1621884663387&imagePreview=1)

In bright green, territory of Nagorno-Karabakh agreed in 1994; in soft green, territory controlled by Armenia until this summer [Furfur/Wikipedia].

A new war?

There are several possible outcomes for the current status . The most likely is a battle over small and not particularly important areas, allowing for the symbolic declaration of a "victory". The problem centres on the fact that each opponent may have a very different view of things, so that a new strand of confrontation is inevitable, raising the stakes of the conflict, and leading to less chance of understanding between the parties.

Although unlikely, many analysts do not rule out the possibility that the current escalation is part of the preparations for negotiations and is necessary to shore up diplomatic positions and increase pressure on the opponent before talks resume.

Whatever the reasoning behind the armed clashes, one thing is clear: the importance of military force in the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process is growing by the day. The absence of talks is becoming critical. If the Karabakh pendulum does not swing from generals to diplomats soon, it may become irreparable. And it will be then that the prospects of another regional war breaking out once again will cease to be a mere scenario described by experts.

While Russia continues to insist that there is no other option but a peaceful way forward, the contact line between the two sides in Nagorno-Karabakh has become the most militarised area in Europe. Many experts have repeatedly suggested as a possible scenario that Azerbaijan might decide to launch a military operation to regain its lost territory. source The country, whose main source of income is its Caspian Sea oil wealth, has spent billions of dollars on new weaponry. Moreover, it is Azerbaijan that has replaced Russia as the largest carrier of natural gas to Turkey.

A major consequence of the conflict centres on potential losses for Russia and Iran. A further casualty of the conflict may be Russia's position as Eurasia's leader. Another argument is based on the Turkish committee , which has demanded Armenia's withdrawal from Azerbaijani lands. The problem is that the members of committee, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, are also members of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), led by Russia together with Armenia. On the other hand, Iran sample also panics over Turkey's total solidarity with Azerbaijan, as more Azeris live in Iranian Azerbaijan than in the Republic of Azerbaijan.

This is one of the many conflicts that exemplify the new and current "style" of warfare, where major powers place themselves at the back of small conflicts. However, the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh may be small in size, but not in importance, as in addition to contributing to the continued destabilisation of the Caucasus area , it may affect neighbouring powers and even Europe. The West should give it the importance it deserves, because if it continues along the same lines, the door is open to a more violent, extensive and prolonged armed conflict.

COMMENTARY / Luis Ángel Díaz Robredo*.

It may seem sarcastic to some, and even cruel, to hear that these circumstances of a global pandemic by COVID-19 are interesting times for social and individual psychology. And it may be even stranger to take these difficult times into account when establishing relations with the security and defence of states.

First of all, we must point out the obvious: the current circumstances are exceptional, as we have never before known a threat to health that has transcended such diverse and decisive areas as the global Economics , international politics, geo-strategy, industry, demography... Individuals and institutions were not prepared a few months ago and, even today, we are dealing with them with a certain degree of improvisation. The fees mortality and contagion rates have skyrocketed and the resources mobilised by the public administration are unknown to date. Without going any further, the Balmis operation -mission statement of support against the pandemic, organised and executed by the Ministry of Defence - has deployed 20,000 interventions, during 98 days of state of alarm and with a total of 188,713 military personnel mobilised.

In addition to the health work of disinfection, logistics and health support, there have been other tasks more typical of social control, such as the presence of the military in the streets and at critical points or reinforcement at borders. This work, which some people may find disconcerting due to its unusual nature of authority over the population itself, is justified by atypical group behaviour that we have observed since the beginning of the pandemic. Suffice it to cite a few Spanish examples that reflect how at certain times there has been behaviour that is not very logical for social imitation, such as the accumulation of basic necessities (food) or not so basic necessities (toilet paper) that emptied supermarket shelves for a few hours.

There have also been moments of lack of solidarity and even some social tension due to the fear of contagion against vulnerable groups, such as elderly people with COVID-19 who were transferred from one town to another and were booed by the neighbourhood that received them and had to be escorted by the police. Also, infrequently but equally negative and unsupportive, there have been cases in which some health workers suffered fear and rejection by their neighbours. And lately, the sanctioning and arrest of people who did not respect the rules of social distance and individual protection has been another common action of the authorities and State Security Forces and Corps. These events, which fortunately have been limited and dealt with quickly by the authorities, have been far outweighed by many other positive social behaviours of solidarity, altruism and generosity among citizens.

However, since national security must consider not only ideal scenarios but also situations with shortcomings or potential risks, these social variables must be taken into account when establishing a strategy.

Secondly, the flow of information has been a veritable tsunami of forces and interests that have overwhelmed the information capacities of entire societies, business groups and even individuals. Official media, private media, social networks and even anonymous groups with destabilising interests have competed in this game for citizens' attention. If this status has shown anything, it is that too much information can be as disabling as too little information, and that even the use of false, incomplete or somehow manipulated information makes us more susceptible to influence by the public.

This poses clear dangers to social stability, the operation of health services, the facilitation of organised crime and even the mental health of the population.

Thirdly and finally, we cannot forget that society and our institutions - including those related to security and defence - have their greatest weakness and strength based on the people who make them up. If there is one thing that the pandemic is putting at test it is the psychological strength of individuals due to the circumstance of uncertainty about the present and future, management fear of illness and death, and an innate need for attachment to social relationships. Our ability to cope with this new VUCA (Vulnerability, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity) scenario that affects each and every social and professional

social and professional environments requires a strong leadership style, adapted to this demanding status , authentic and based on group values. There is no unilateral solution today, except through the efforts of many. It is not empty words to affirm that the resilience of a society, of an Armed Forces or of a human group , is based on working together, fighting together, suffering together, with a cohesion and a team work properly trained.

That said, we can understand that psychological variables - at the individual and grouplevels - are at play in this pandemic status and that we can and should use the knowledge provided by Psychology as a serious science, adapted to real needs and in a constructive spirit, to plan the tactics and strategy of the current and future scenarios arising from Covid-19.

Undoubtedly, these are interesting times for psychology.

* Luis Ángel Díaz Robredo is a professor at Schoolof Educationand Psychology at the University of Navarra.

![Members of Colombia's National Liberation Army [Voces de Colombia]. Members of Colombia's National Liberation Army [Voces de Colombia].](/documents/10174/16849987/crime-terrorism-blog.jpg)

▲ Members of Colombia's National Liberation Army [Voces de Colombia] [Voices of Colombia].

ESSAY / Angel Martos

Terrorism and transnational organised crime are some of the most relevant topics nowadays in international security. The former represents a traditional threat that has been present during most our recent history, especially since the second half of the twentieth century. International organised crime, on the other hand, has taken place throughout history in multiple ways. Examples can be found even in the pre-industrial era: In rural and coastal areas, where law enforcement was weaker, bandits and pirates all over the world made considerable profit from hijacking vehicles along trade routes and roads, demanding a payment or simply looting the goods that the merchants carried. The phenomenon has evolved into complex sets of interconnected criminal networks that operate globally and in organised way, sometimes even with the help of the authorities.

In this paper, the author will analyze the close interaction between terrorism and organized crime often dubbed the "crime-terror continuum". After explaining the main tenets of this theory, a case study will be presented. It is the network of relations that exists in Latin America which links terrorist groups with drug cartels. The evolution of some of these organisations into a hybrid comprising terrorist and criminal activity will also be studied.

Defining concepts

The crime-terror nexus is agreed to have been consolidated in the post-Cold War era. After the 9/11 attacks, the academic community began to analyze more deeply and thoroughly the threat that terrorism represented for international security. However, there is one specific topic that was not paid much attention until some years later: the financing of terrorist activity. Due to the decline of state sponsorship for terrorism, these groups have managed to look for funding by partnering with organised criminal groups or engaging in illicit activities themselves. Starting in the 1980s with what later came to be known as narco-terrorism, the use of organised crime by terrorist groups became mainstream in the 1990s. Taxing drug trade and credit-card fraud are the two most common sources of revenues for these groups (Makarenko, 2010).

The basic level of relationship that exists between two groups of such different nature is an alliance. Terrorists may look for different objectives when allying with organised crime groups. For example, they may seek expert knowledge (money-laundering, counterfeiting, bomb-making, etc.) or access to smuggling routes. Even if the alliances may seem to be only beneficial for terrorist groups, criminal networks benefit from the destabilizing effect terrorism has over political institutions, and from the additional effort law enforcement agencies need to do to combat terrorism, investing resources that will not be available to fight other crimes. Theirs is a symbiotic relation in which both actors win. A popular example in the international realm is the protection that Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) offered to drug traders that smuggle cocaine from South America through West and North Africa towards Europe. During the last decade, the terrorist organisation charged a fee on the shipments in exchange for its protection along the route (Vardy, 2009).

The convergence of organisations

Both types of organisations can converge into one up to the point that the resulting group can change its motives and objectives from one side to the other of the continuum, constituting a hybrid organisation whose defining points and objectives blur. An organisation of this nature could be both a criminal group with political motivations, and a terrorist group interested in criminal profits. The first one may for example be interested in getting involved in political processes and institutions or may use violence to gain a monopolized control over a lucrative economic sector.

Criminal and terrorist groups mutate to be able to carry out by themselves a wider range of activities (political and financial) while avoiding competitiveness, misunderstandings and threats to their internal security. This phenomenon was popularized after the 1990s, when criminal groups sought to manipulate the operational conditions of weak states, while terrorist groups sought to find new financial sources other than the declining state sponsors. A clear example of this can be found in the Italian Mafia during the 1990s. A series of deliberate bombing attacks were reported in key locations such as the Uffizi Galleries in Florence and the church of St. John Lateran in Rome. The target was not a specific enemy, but rather the public opinion and political authorities (the Anti-Mafia Commission) who received a warning for having passed legislation unfavorable to the interests of the criminal group. Another example far away from Europe and its traditional criminal groups can be found in Brazil. In the early 2000s, a newly elected government carried out a crackdown on several criminal organizations like the Red Commandthe Amigos dos Amigos, and the group Third Commandwhich reacted violently by unleashing brutal terrorist attacks on governmental buildings and police officers. These attacks gave the Administration no other choice but to give those groups back the immunity with which they had always operated in Rio de Janeiro.

On the other side of the relationship, terrorist organisations have also engaged in criminal activities, most notably illicit drug trade, in what has been a common pattern since the 1970s. Groups like the FARC, ETA, the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), or Shining Path are among them. The PKK, for example, made most of its finances using its advantageous geographic location as well as the Balkan routes of entry into Europe to smuggle heroin from Asia into Europe. In yet another example, Hezbollah is said to protect heroin and cocaine laboratories in the Bekaa Valley, in Lebanon.

Drug trafficking is not the only activity used by terrorist groups. Other criminal activities serve the same purpose. For example, wholesale credit-card fraud all around Europe is used by Al Qaeda to gain profits (US$ 1 million a month). Furthermore, counterfeit products smuggling has been extensively used by paramilitary organizations in Northern Ireland and Albanian extremist groups to finance their activities.

Sometimes, the fusion of both activities reaches a point where the political cause that once motivated the terrorist activity of a group ends or weakens, and instead of disbanding, it drifts toward the criminal side and morphs into an organised criminal association with no political motivations) that the convergence thesis identifies is the one of terrorist organisations that have ultimately maintained their political façade for legitimation purposes but that their real motivations and objectives have mutated into those of a criminal group. They are thus able to attract recruits via 2 sources, their political and their financial one. Abu Sayyaf, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and FARC are illustrative of this. Abu Sayyaf, originally founded to establish an Islamic republic in the territory comprising Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago (Philippines), is now dedicated exclusively to kidnapping and marijuana plantations. The former granted them US$ 20 million only in 2000. Colombian FARC, since the 1990s, has followed the same path: according to Paul Wilkinson, they have evolved from a revolutionary group that had state-wide support into a criminal guerrilla involved in protection of crops and laboratories, also acting as "middlemen" between farmers and cartels; kidnapping, and extortion. By the beginning of our century, they controlled 40 per cent of Colombia's territory and received an annual revenue of US$ 500 million (McDermott, 2003).

"Black hole states

The ultimate danger the convergence between criminal and terrorist groups may present is a situation where a weak or failed state becomes a safe haven for the operations of hybrid organisations like those described before. This is known as the "black hole" syndrome. Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Angola, Sierra Leone and North Korea are examples of states falling into this category. Other regions, such as the North-West Frontier Province in Pakistan, and others in Indonesia and Thailand in which the government presence is weak can also be considered as such.

Afghanistan has been considered a "black hole state" since at least the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989. Since the beginning of the civil war, the groups involved in it have sought to survive, oftentimes renouncing to their ideological foundations, by engaging in criminal activity such as the production and trafficking of opiates, arms or commodities across the border with Pakistan, together with warlords. The chaos that reigns in the country is a threat not only to the nation itself and its immediate neighbors, but also to the entire world.

The People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) is, on the other hand, considered a criminal state. This is because it has engaged in transnational criminal activities since the 1970s, with its "Bureau 39", a government department that manages the whole criminal activity for creating hard currency (drug trafficking, counterfeiting, money laundering, privacy, etc.). This was proved when the Norwegian government expelled officials of the North Korean embassy in 1976 alleging that they were engaged in the smuggling of narcotics and unlicensed goods (Galeotti, 2001).

Another situation may arise where criminal and terrorist groups deliberately foster regional instability for their own economic benefits. In civil wars, these groups may run the tasks that a state's government would be supposed to run. It is the natural evolution of a territory in which a political criminal organisation or a commercial terrorist group delegitimizes the state and replaces its activity. Examples of this situation are found in the Balkans, Caucasus, southern Thailand and Sierra Leone (Bangura, 1997).

In Sierra Leone, for example, it is now evident that the violence suffered in the 1990s during the rebellion of the Revolutionary United Forces (RUF) had nothing to do with politics or ideals - it was rather a struggle between the guerrilla and the government to crack down on the other party and reap the profits of illicit trade in diamonds. There was no appeal to the population or political discourse whatsoever. The "black hole" thesis illustrates how civil wars in our times are for the most part a legitimisation for the private enrichment of the criminal parties involved and at the same time product of the desire of these parties for the war to never end.

The end of the Cold War saw a shift in the study of the nexus between crime and terrorism. During the previous period, it was a phenomenon only present in Latin America between insurgent groups and drug cartels. It was not until the emergence of Al Qaeda's highly networked and globally interconnected cells that governments realised the level of threat to international security that non-state actors could pose. As long as weak or failed states exist, the crime-terror nexus will be further enhanced. Moreover, the activity of these groups will be buttressed by effects of globalisation such as the increase of open borders policies, immigration flows, international transportation infrastructure, and technological development. Policymakers do not pay enough attention to the criminal activities of both types of organisations. Rather than dealing with the political motivations of a group, what really makes the difference is to focus on its funding resources - credit-card frauds, smuggling, money laundering, etc.

The following section focuses on the crime-terror continuum that exists between illegal drug trade and terrorist networks. This phenomenon has emerged in many regions all around the world, but the case of Latin America, or the Andean region more specifically, represents the paradigm of the characteristics, dangers and opportunities of these situations.

NARCO-TERRORISM CASE STUDY:

When drug trafficking meets political violence

The concept of narco-terrorism was born in recent years as a result of the understanding of illicit drug trade and terrorism as two interconnected phenomena. Traditionally linked with Latin America, the concept can now be found in other parts of the world like, for example, the Golden Crescent (Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan), or the Golden Triangle (Thailand, Laos and Myanmar).

There is no consensus on the convenience and accuracy of the term "narco-terrorism," if only because it may refer to different realities. One can think of narco-terrorism as the use of terrorist attacks by criminal organisations such as the Colombian Medellin Cartel to attain an immediate political goal. Or, from a different point of view, one can think of a terrorist organisation engaging in illicit drug trade to raise funds for its activity. Briefly, according to Tamara Makarenko's Crime-Terror Continuum construct all organisations, no matter the type, could at some point move along this continuum depending on their activities and motivations; from the one extreme of a purely criminal organisation, to the other of a purely political one, or even constituting a hybrid in the middle (Makarenko, 2010).

There is a general perception of a usual interaction between drug-trafficking and terrorist organisations. Here, it is necessary to distinguish between the cooperation of two organisations of each nature, and an organisation carrying out activities under both domains. There are common similarities between the different organisations that can be highlighted to help policymaking more effective.

Both type of organisations cohabit in the same underground domain of society and share the common interest of remaining undiscovered by law enforcement authorities. Also, their transnational operations follow similar patterns. Their structure is vertical in the highest levels of the organisation and turns horizontal in the lowest. Finally, the most sophisticated among them use a cell structure to reduce information sharing to the bare minimum to reduce the risk of the organisation being unveiled if some of its members are arrested.

The main incentive for organisations to cooperate are tangible resources. Revenues from narcotics trafficking might be very helpful for terrorist organisations, while access to explosive material may benefit drug trade organisations. As an example, according to the Executive Director of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in 2004, an estimated US$ 2.3 billion of the total revenue of global drug trade end up in the hands of organisations like Al Qaeda. Another example is the illegal market of weapons emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union, field of interest of both types of networks. On the other hand, intangible resources are similar to tangible in usefulness but different in essence. Intangible resources that drug trafficking organisations possess and can be in the interests of terrorist ones are the expertise on methods and routes of transports, which could be used for terrorist to smuggle goods or people - drug corridors such as the Balkan route or the Northern route. On the other way around, terrorists can share the military tactics, know-how and skills to perpetrate attacks. Some common resources that can be used by both in their benefit are the extended networks and contacts (connections with corrupt officials, safe havens, money laundering facilities, etc.) A good example of the latter can be found in the hiring of ELN members by Pablo Escobar to construct car bombs.

The organisations are, as we have seen, often dependent on the same resources, communications, and even suppliers. This does not lead to cooperation, but rather to competition, even to conflict. Examples can be traced back to the 1980s in Peru when clashes erupted between drug traffickers and the terrorist Shining Pathand in Colombia when drug cartels and the FARC clashed for territorial matters. Even the protection of crops terrorists offer to drug traffickers is one of the main drivers of conflict, even if they do find common grounds of understanding most of the time; for example, in terms of government, revenue-motivated organisations are a threat to the state as they fight to weaken some parts of it such as law enforcement or jurisdiction, while politically-motivated ones wish not only to undermine the state but to radically change its structures to fit their ideological vision (state-run economy, religious-based society, etc.).

The terrorism and drug connection in the Andean Region

Nowhere has the use of illicit drug trade as a source of funds for terrorism been so developed as in the Andean Region (Steinitz, 2002). Leftist groups such as FARC and Peruvian Shining Pathas well as right-wing paramilitary organisations such as the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) are involved in this activity. At the beginning, the engagement between terrorists and drug traffickers was limited only to fees imposed by the former on the latter in exchange for the protection of crops, labs and shipments. Later, FARC and AUC have further expanded this engagement and are now involved in the early stages of the traffic itself - the main substance being cocaine, and the main reward money and arms from the drug syndicates. The terrorist cells can be therefore considered a hybrid of political and criminal groups. The following paragraphs will further analyze each case.

Peru's Shining Path

Shining Path (SL) started to operate in the Huallaga Valley, a strong Peruvian coca region, several years after its foundation, in 1980. Peru was at the time the world's first producer of coca leaf. The plant was then processed into coca paste and transported to Colombian laboratories by traffickers. Arguably, the desire for profit from the coca business rather than for political influence was the ultimate motive for Shining Path's expansion into the region. SL protected the crops and taxed the production and transportation of coca paste: the 1991 document "Economic Balance of the Shining Path" shows that the group charged US$ 3,000-7,000 per flight leaving Huallaga. Taxes were also levied in exchange for a service that the group provided the cocaleros: negotiating favourable prices with the traffickers. In the late 1980s, SL's annual income from the business was estimated at US$ 15-100 million (McClintock, 1998).

The Peruvian government's fight against SL represents a milestone in the fight against the terrorism-crime nexus. Lima set up a political-military command which focused on combating terrorism while ignoring drugs, because a reasonable percentage of the Peruvian population eked out a living by working in the coca fields. The government also avoided using the police as they were seen as highly corruptible. They succeeded in gaining the support of peasant growers and traffickers of Huallaga Valley, a valuable source of intelligence to use against SL. The latter finally left the Valley.

But it was not a final victory. Due to the vacuum SL left, the now more powerful traffickers reduced the prices paid for the coca leaf. SL was no longer there to act as an intermediary in defence of peasants and minor traffickers, so thanks to the new lower prices, the cocaine market experienced a boom. The military deployed in the area started to accept bribes in exchange for their laissez-faire attitude, becoming increasingly corrupted. President Fujimori in 1996 carried out a strategy of interdiction of the flights that departed from the Valley carrying coca paste to Colombia, causing the traffickers and farmers to flee and the coca leaf price to fall notably. However, this environment did not last long, and the country is experiencing a rise in drug trade and terrorist subversive activities.

The Colombian nexus expands

The collapse of the Soviet Union and an economic crisis in Cuba diminished the amount of aid that the FARC could receive. After the government's crackdown, with the help of Washington, of the Medellin and Cali cartels, the drug business in Colombia was seized by numerous smaller networks. There was not any significant reduction of the cocaine flow into the United States. The FARC benefited greatly from the neighbouring states' actions, gaining privileged access to drug money. Peru under Fujimori had cracked down on the coca paste transports, and Bolivia's government had also put under strict surveillance its domestic drug cultivation. This elimination of competitors caused a doubling of coca production in Colombia between 1995 and 2000. Moreover, opium poppy cultivation also grew significantly and gained relevance in the US' East-coast market. The FARC also benefited from this opportunity.

According to the Colombian government, in 1998 the terrorist groups earned US$ 551 million from drug, US$ 311 million from extortion, and US$ 236 million from kidnapping. So much so that the organization has been able to pay higher salaries to its recruits than the Colombian army pays its soldiers. By 2000, the FARC had an estimated 15,000-20,000 recruits in more than 70 fronts, de facto controlling 1/3 of the nation's territory. Most of the criminal-derived money in the country comes nowadays from taxation and protection of the drug business. According to the Colombian Military, more than half both the FARC's fronts were involved in the collection of funds by the beginning of the 2000s decade, compared to 40% approx. of AUC fronts (Rebasa and Chalk, 1999).

The situation that was created in both scenarios required created a chaos in which the drug cartels, the cultivation syndicates and the terrorist organisations were the strongest actors. This makes it a very unstable environment for the peoples that lived in the territories under criminal/terrorist control. The tactics of law enforcement agents and government, in these cases, need to be carefully planned, so that multilateral counter-drug/counter-terrorist strategies can satisfactorily address threats existing at multiple dimensions. In the following section, the author will review some key aspects of the policies carried out by the US government in this domain.

The "War on Drugs" and the "War on Terror".

Since 9/11, policies considering both threats as being intertwined have become more and more popular. The separation of counter terrorism and counter-narcotics has faded significantly. Although in the Tashkent Conferences of 1999-2000 the necessary link between both was already mentioned, the milestone of cooperative policies is the Resolution 1373 of the UN Security Council (Björnehed, 2006). In it, emphasis is given to the close connection between terrorism and all kinds of organised crime, and therefore coordination at national, regional and global level is said to be necessary. War on drugs and war on terror should no longer be two separate plans of action.

The effectiveness of a policy that wishes to undermine the threat of illicit drug trade and terrorism is to a high degree dependent on successful intelligence gathering. Information about networks, suspects, shipments, projects, etc. benefits agencies fighting drug trafficking as well as those fighting terrorism, since the resources are most of the times shared. Narco-terrorism nexus is also present in legal acts, with the aim of blocking loopholes in law enforcement efforts. Examples are the Victory Act and the Patriot Act, passed in the US. Recognizing the natural link and cooperation between drug trade and terrorism leads to security analysts developing more holistic theories for policymakers to implement more accurate and useful measures.

However, there are many aspects in which illicit drug trade and terrorist activity differ, and so do the measures that should be taken against them. An example of a failure to understand this point can be found in Afghanistan, where the Taliban in 2000 set a ban on poppy cultivation which resulted in a strong increase of its price, this being a victory for traffickers since the trade did not stop. Another idea to have in mind is that strategies of a war on drugs differ greatly depending on the nature of the country: whether it is solely a consumer like the UK or a producer and consumer like Tajikistan. In regard to terrorism, the measures adopted to undermine it (diplomacy, foreign aid, democratization, etc.) may have minimal effect on the fight against drug trade.

Sometimes, the risk of unifying counter-policies is leaving some areas in which cooperation is not present unattended. Certain areas are suitable for a comprehensive approach such as intelligence gathering, law enforcement and security devices, while others such as drug rehabilitation are not mutually beneficial. Not distinguishing the different motivations and goals among organisations can lead to a failed homogenous policy.

CONCLUSIONS:

Multilevel threats demand multilevel solutions

Terrorism has traditionally been considered a threat to national and international security, while illicit drug trade a threat to human security. This perception derives from the effects of drugs in a consumer country, although war on drugs policies are usually aimed at supplier ones. Although it was already constituting a threat to regional stability during the twentieth century, it was not considered a crucial political issue until 9/11 attacks, when the cooperative link between criminal and terrorist organisations became evident. An example of unequal attention paid to both threats can be found in US's Plan Colombia in 2000: one of the main advocators of the legislation stated that the primary focus was on counter-drug, so the United States would not engage with Colombian counterinsurgency efforts (Vaicius, Ingrid and Isacson, 2003).The same type of failure was also seen in Afghanistan but in the opposite way, when the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) completely neglected any action against drug traffickers, the trade or the production itself.

The merging of drug trafficking and terrorism as two overlapping threats have encouraged authorities to develop common policies of intelligence gathering and law enforcement. The similarities between organisations engaged in each activity are the main reason for this. However, the differences between them are also relevant, and should be taken into consideration for the counter policies to be accurate enough.

Evidence of a substantial link between terrorists and criminals has been proved all along our recent history. Around the world, leaders of mafias and terrorist commanders have oftentimes worked together when they felt that their objectives were close, if not similar. When cohabitating in the outlaw world, groups tend to offer each other help, usually in exchange for something. This is part of human behaviour. Added to the phenomenon of globalisation, lines tend to be blurred for international security authorities, and thus for the survival of organisations acting transnationally.

The consequences can be noticed especially in Latin America, and more specifically in organisations such as the FARC. We can no longer tell what are the specific objectives and the motivations that pushed youngsters to flee towards the mountains to learn to shoot and fabricate bombs. Is it a political aspiration? Or is it rather an economic necessity? The reason why we cannot answer this question without leaving aside a substantial part of the explanation is the evolution of the once terrorist organisation into a hybrid group that moves all along the crime-terror continuum.

The ideas of Makarenko, Björnehed and Steinitz have helped the international community in its duty to protect its societies. It cannot be expected for affected societies to live in peace if the competent authorities try to tackle its structural security issues only through the counter-terrorist approach or through the organised crime lens. The hybrid threats that the world is suffering in the twenty-first century demand hybrid solutions.

REFERENCES

Bangura, Y. (1997) 'Understanding the political and cultural dynamics of the sierra leone war', Africa Development, vol. 22, no. 3/4 [Accessed 10 April 2020].

Björnehed, E., 2006. Narco-Terrorism: The Merger Of The War On Drugs And The War On Terror. [online] Taylor & Francis. Available at [Accessed 10 April 2020].

Galeotti, M. (2001) 'Criminalisation of the DPRK', Jane's Intelligence Review, vol. 13, no. 3 (March) [Accessed 10 April 2020].

Makarenko, T., 2010. The Crime-Terror Continuum: Tracing The Interplay Between Transnational Organised Crime And Terrorism. [online] Taylor & Francis. Available at [Accessed 3 April 2020].

McClintock, C. Revolutionary Movements in Latin America: El Salvador's FMLN and Peru's Shining Path (Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1998), p. 341 [Accessed 10 April 2020].

McDermott, J. (2003) 'Financing insurgents in Colombia', Jane's Intelligence Review, vol. 15, no. 2

(February) [Accessed 10 April 2020].

Mutschke, R., (2000) 'The threat posed by organised crime, international drug trafficking and terrorism', written testimony to the General Secretariat Hearing of the Committee on the Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime (13 December) [Accessed 14 June 2020].

Rebasa and Chalk, pp. 32-33; "To Turn the Heroin Tide," Washington Post, February 22, 1999, p. A9; "Colombian Paramilitary Chief Shows Face," Associated Press, March 2, 2000.

Steinitz, M., 2002. The Terrorism And Drug Connection In Latin America'S Andean Region. [online] Brian Loveman, San Diego State University. Available at [Accessed 10 April 2020].

Vaicius, Ingrid and Isacson, Adam "'The War on Drugs' meets the 'War on Terror' " (CIP International Policy Report February 2003) p. 13.

Vardy, N., 2009. Al-Qaeda's New Business Model: Cocaine And Human Trafficking. [online] Forbes. Available at [Accessed 14 June 2020].

[Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization. Oxford University Press. Oxford (New York), 2006. 822 p.]

review / Salvador Sánchez Tapia

Among the many authors who have written on the phenomenon of war in recent decades, the name of Azar Gat stands out. From his Chair at Tel-Aviv University, this author has devoted an important part of his academic degree program to theorising on the war from different angles, a phenomenon that he knows directly from his position as a reservist in the Tsahal (Israeli Defence Forces).

Among the many authors who have written on the phenomenon of war in recent decades, the name of Azar Gat stands out. From his Chair at Tel-Aviv University, this author has devoted an important part of his academic degree program to theorising on the war from different angles, a phenomenon that he knows directly from his position as a reservist in the Tsahal (Israeli Defence Forces).

War in Human Civilization is a monumental work in which the author sample his great erudition, together with his ability to deal with and study the phenomenon of war, combining the employment of fields of knowledge as diverse as history, Economics, biology, archaeology and anthropology, placing them at the service of the goal of his work, which is none other than that of elucidating what has moved and moves human groups towards war.

Throughout the almost seven hundred pages of this extensive work, Gat makes a study of the historical evolution of the phenomenon of war in which he combines a chronological approach, which we could call "conventional", with a synchronic one in which he puts in parallel similar stages of the evolution of war in different civilisations in order to compare cultures which, at a given historical moment, were at different Degrees of development and show how in all of them war went through a similar process of evolution.

In his initial approach, Gat promises an analysis that transcends any particular culture to consider the evolution of war in a general way, from its inception to the present day. The promise, however, is broken when he reaches the medieval period, for from then on he adopts a distinctly Eurocentric view, which he justifies with the argument that the Western model of war has been exported to other continents and adopted by other cultures, which, while not entirely false, leaves the reader with a somewhat incomplete view of the phenomenon.

Azar Gat dives into the origin of the human species to try to elucidate whether the phenomenon of war makes it different from the rest of the species, and to try to determine whether conflict is an innate phenomenon in the species or whether, on the contrary, it is a learned behaviour.

On the first question, the book concludes that nothing makes us different from other species because, despite Rousseaunian visions based on the "good savage" that were so in vogue in the 1960s, the reality sample is that intra-species violence, which was considered to be unique to humans, is in fact something shared with other species. On the second question, Gat takes the eclectic view that aggression is both innate and optional, a basic survival choice that is nonetheless exercised optionally, and developed through social learning.

Throughout the book's historical journey, the idea, formulated in the first chapters, that the ultimate causes of war are evolutionary in nature and have to do with the struggle for the survival of the species, appears as a leitmotif.

According to this approach, conflict would be rooted in competition for resources and better reproductive opportunities. Although the human development towards increasingly complex societies has eventually obscured it, this logic would still guide human behaviour today, mainly through the bequest of proximate mechanisms implied by human desires.

An important chapter in the book is the author's dissection of the theory, first advanced during the Enlightenment, of the Democratic Peace. Gat does not refute the theory, but puts it in a new light. If, in its original definition, it argues that liberal and democratic regimes are averse to war and that, therefore, the spread of liberalism will advance peace among nations, Gat argues that it is the growth of wealth that actually serves that spread, and that welfare and the interrelationship that trade fosters are the real drivers of democratic peace.

Two are, therefore, the two main conclusions of the work: that conflict is the rule in a nature in which organisms compete with each other for survival and reproduction in an environment of scarce resources, and that, recently, the development of liberalism in the western world has generated in this environment a feeling of repugnance towards war that translates into an almost absolute rejection of it in favour of other strategies based on cooperation.

Azar Gat recognises that a significant part of the human race is still a long way from liberal and democratic models, let alone the achievement of Degree of well-being and wealth, which, in his view, goes hand in hand with the rejection of war. Although he does not say so openly, it can be inferred from his speech that this is, nevertheless, the direction in which humanity is heading and that, the day it reaches the necessary conditions for this, war will finally be eradicated from the Earth.

Against this idea, one could argue the ever-present possibility of regression of the liberal system due to the demographic pressure to which it is subjected, or because of some global event that provokes it; or that other systems, equally rich but not liberal, will replace the world of democracies in world domination.

reference letter The book is a must for any scholar or reader interested in the nature and evolution of the phenomenon of war, and is a must for any scholar or reader interested in the nature and evolution of the phenomenon of war. Written with great erudition, and with a profusion of data that, at times, makes it somewhat harsh, War in Human Civilization is, without a doubt, an important contribution to the knowledge of war that is essential reading.

![VCR 8x8 programme [framework Romero/MDE]. VCR 8x8 programme [framework Romero/MDE].](/documents/10174/16849987/ddn-blog.jpg)

▲ VCR 8x8 programme [framework Romero/MDE].

COMMENTARY / Salvador Sánchez Tapia

After a gap of eight years since the publication of the last one in 2012, on 11 June, the President of the Government signed a new National Defence Directive (DDN), marking the beginning of a new Defence Planning cycle which, according to agreement as established by Defence Order 60/2015, must be valid for six years.

The essay of the DDN 20 is a laudable effort to bring National Defence up to date with the challenges of a complex strategic environment in continuous transformation. Its essay also offers an excellent opportunity to build along the way an intellectual community on this important issue, which will be fundamental throughout the cycle.

This article provides a preliminary analysis of the DDN 20, focusing on its most relevant aspects. In a first approximation, the official document follows the line, already enshrined in other Directives, of subsuming the essentially military concept of Defence within the broader concept of Security, which affects all the capabilities of the State. In this sense, the first difficulty that the DDN 20 has had to overcome is precisely the lack of a statutory document similar to the DDN, drafted at the level of National Security, to illuminate and guide it. To tell the truth, the void has not been total, since, as the DDN 20 states in its introduction, there is a National Security Strategy (NSS) which, although published in 2017, has served as reference letter in its elaboration, despite the evident lack of consistency between the strategic scenarios described in both documents.

In this respect, it is precisely worth noting the lack of specificity with which the new DDN defines the strategic scenario, compared to the somewhat greater specificity of the ESN. The DDN 20 draws a vague, almost generic scenario, applicable almost unchanged to any nation in the world, without reference to specific geographical areas; an accumulation of threats and risks to security with an impact on Defence, none of which appears to be more likely or more dangerous, and to which is added the recognition of changes in the international order that once again bring the possibility of major armed conflicts closer.

Such an approach makes it difficult to subsequently define defence objectives and guidelines for action and, perhaps for this reason, there are certain inconsistencies between the three parts of the document. It is striking that, although the document raises certificate, somewhat hastily, the possibility of the emergence of COVID-19, the possibility of a pandemic not being triggered is not considered in the description of the strategic scenario, something that, on the other hand, is included in ESN 17.

Along with the description of this scenario, the DDN 20 is interspersed with a series of considerations of a programmatic nature, which are in themselves positive and relevant, but which have little to do with what is to be expected in a document of this nature, designed to guide National Defence planning. In some cases, such as the promotion of the gender perspective, or the improvement of the quality of life of staff in its dimensions of improving living facilities, reconciling professional and family life, and reintegration into civilian life once the link with the Armed Forces has ended, the considerations are more typical of the Policy of staff of the department than of a DDN. In others, such as the obligation to respect local cultures in military operations, they seem more subject typical of the Royal Ordinances or another subject code of ethics.

Undoubtedly motivated by the COVID-19 emergency, and in view of the role that the Armed Forces have assumed during it, the DDN emphasises the importance of partnership missions with and in support of civilian authorities, something that is inherent to the Armed Forces, and establishes the specific goal of acquiring capabilities that allow for the partnership and support of these authorities in crisis and emergency situations.

The management of the pandemic may have highlighted gaps in response capabilities, shortcomings in coordination instruments, etc., thereby opening a window of opportunity to make progress in this area and produce a more effective response in the future. Nonetheless, it is important to guard against the possibility, opened up by this DDN, of losing sight of the central tasks of the armed forces, to prevent an excessive focus on missions in support of the civilian population from ending up distorting their organisation, manning and training, thereby impairing the deterrence capacity of the armies and their combat operability.

The DDN also contains the customary reference letter, which is necessary to promote a true Defence Culture among Spaniards. The accredited specialization is justified by the role that the Ministry of Defence should play in this effort. However, it is not the defence sector that needs to be reminded of the importance of this issue. The impact of any effort to promote Defence Culture will be limited if it is not assumed as its own by other ministries Departments , as well as by all State administrations, being aware that it is not possible to generate a Defence Culture without a prior consensus at the national level on such essential issues as the objectives or values shared by all. It is perhaps on this aspect that the emphasis should be placed.

Perhaps the most controversial point of the DDN 20 is that of financing. Achieving the objectives set out in the document requires sustained financial investment over time to break the current ceiling of expense in defence. Maintaining the Armed Forces among the technological elite, substantially improving the quality of life of the professional staff -which begins with providing them with the equipment that best guarantees their survival and superiority on the battlefield-, reinforcing the capacity to support civilian authorities in emergency situations, strengthening intelligence and action capabilities in cyberspace, or meeting with guarantees the operational obligations derived from our active participation in international organisations, for which, moreover, a commitment has been made to strengthen them by up to 50% for a period of one year, is as necessary as it is costly.

The DDN 20 recognises this in its final paragraph when it states that the development of the document's guidelines will require the necessary funding. This statement, however, is little more than an acknowledgement of the obvious, and is not accompanied by any commitment or guarantee of funding. Bearing in mind the important commitments already signed by the Ministry with the pending Special Armaments Programmes, and in view of the economic-financial panorama that is on the horizon due to the effects of COVID-19, which has led the JEME to announce the arrival of a period of austerity for the Army, and which deserves to be listed among the main threats to national security, it seems difficult that the objectives of the DDN 20 can be covered in the terms it sets out. This is the real Achilles' heel of the document, which could make it little more than a dead letter.

In conclusion, the issuance of a new DDN is to be welcomed as an effort to update National Defence policy, even in the absence of a similar instrument that periodically articulates the level of Security Policy in which Defence Policy should be subsumed.

The emergence of COVID-19 seems to have overtaken the document, causing it to lose some of its validity and calling into question not only the will, but also the real capacity to achieve the ambitious goals it proposes. At least it is possible that the document may act, even in a limited way, as a kind of shield to protect the Defence sector against the scenario of scarce resources that Spain will undoubtedly experience in the coming years.

![Crossroads in Minneapolis where George Floyd was stopped by local police [Fibonacci Blue]. Crossroads in Minneapolis where George Floyd was stopped by local police [Fibonacci Blue].](/documents/10174/16849987/george-floyd-blog.jpg)

▲ Crossroads in Minneapolis where George Floyd was stopped by local police [Fibonacci Blue].

COMMENTARY / Salvador Sánchez Tapia [Brigadier General (Res.)].

In a controversial public statement on 2 June, US President Donald Trump threatened to deploy armed forces units to contain riots sparked by the death of African-American George Floyd at the hands of a police officer in Minnesota, and to maintain law and order if they escalate in violence.

Regardless of the seriousness of the event, and beyond the fact that the incident has been politicised and is being employee used as a platform for expressing rejection of Trump's presidency, the possibility raised by the president poses an almost unprecedented challenge to civil-military relations in the United States.

For reasons rooted in its pre-independence past, the United States maintains a certain caution against the possibility that armed forces can be used domestically against citizens by whoever holds power. For this reason, when the Founding Fathers drafted the Constitution, while authorising the congress to organise and maintain armies, they explicitly limited their funding to a maximum of two years.

Against this backdrop, and against the background of the tension between the Federation and the states, American legislation has tried to limit the employment of the Armed Forces in domestic tasks. Thus, since 1878, the Posse Comitatus Since 1878, for example, the Armed Forces Act has limited the possibility of using them to carry out law and order missions that the states, including the National Guard, are responsible for carrying out with their own resources.

One of the exceptions to this rule is the Insurrection Act of 1807, invoked precisely by President Trump as an argument in favour of the legality of a possible decision by employment. This is despite the fact that this law is restrictive in spirit, as it requires the cooperation of the states in its application, and because it is designed for extreme cases in which the states are unable, or unwilling, to maintain order, circumstances that do not seem applicable to the case at hand.

The controversial nature of advertisement is attested to by the fact that voices as authoritative and so little inclined to publicly break its neutrality as that of Lieutenant General (ret.) James Mattis, Secretary of Defence of the Trump Administration until his premature removal in December 2018, or Lieutenant General (ret.) Martin Dempsey, head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff between 2011 and 2015, have spoken out against it. ) Martin Dempsey, head of the board Chiefs of Staff between 2011 and 2015, have spoken out against this employment, joining the statements made by former presidents as disparate as George W. Bush and Barack Obama, or those of the Secretary of Defence himself, Mark Esper, whose position against the possibility of using the Armed Forces in this status has recently been made clear.

The presidential advertisement has opened up a crisis in the usually stable US civil-military relations (CMR). Beyond the scope of the United States, the profound question, which affects the very core of CMR in a democratic state, is none other than whether or not it is appropriate to use the armed forces in public order or, in a broader sense, domestic tasks, and the risks associated with such a decision.

In the 1990s, Michael C. Desch, one of the leading authorities in the field of CMR, identified the correlation between the missions entrusted to the armed forces by a state and the quality of its civil-military relations, concluding that foreign-oriented military missions are the most conducive to healthy CMR, while non-military domestic missions are likely to generate various CMR pathologies.

Generally speaking, the existence of armed forces in any state is primarily motivated by the need to protect the state against any threat from outside. employment In order to carry out such a high task with guarantees, armies are equipped and trained for the lethal use of force, unlike police forces, which are equipped and trained for a minimal and gradual use of force, which only becomes lethal in the most extreme, exceptional cases. In the first case, it is a matter of confronting an armed enemy intent on destroying one's own forces. In the second, force is used to confront citizens who may, in some cases, use violence, but who remain, after all, compatriots.

When military forces are employed in tasks of this nature, there is always a risk that they will produce a response in accordance with their training, which may be excessive in a law and order scenario. The consequences, in such a case, can be very negative. In the worst case, and above all other considerations, the employment may result in a perhaps avoidable loss of life. Moreover, from the CMR's point of view, the soldiers that the nation submission has for its external defence could become, in the eyes of the public, the enemies of those they are supposed to defend.

The damage this can do to civil-military relations, to national defence and to the quality of a state's democracy is difficult to measure, but it can be intuited if one considers that, in a democratic system, the armed forces cannot live without the support of their fellow citizens, who see them as a beneficial force for the nation and to whose members they extend their recognition as its loyal and selfless servants.

The abuse of employment of the armed forces in domestic tasks can also deteriorate their already complex preparation, weakening them for the execution of the missions for which they were conceived. It may also end up conditioning their organisation and equipment to the detriment, once again, of their essential tasks.

On the other hand, and although today we are far from such a scenario, this employment could gradually lead to a progressive expansion of the tasks of the Armed Forces, which would extend their control over purely civilian activities and see their range of tasks increasingly broadened, displacing other agencies in their execution, which could, undesirably, atrophy.

In such a scenario, the military institution could cease to be perceived as a disinterested actor and come to be seen as a competitor with particular interests, and with a capacity for control that it could use to its own advantage, even if this were at odds with the nation's interest. Such a status would, over time, lead hand in hand to the politicisation of the armed forces, from which would follow another damage to WRCs that is difficult to quantify.

Decisions such as President Trump's may ultimately place members of the armed forces in the grave moral dilemma of using force against their fellow citizens, or disobeying the president's orders. Because of its seriousness, therefore, the decision to commit the armed forces to such tasks should be taken exceptionally and after careful consideration.

It is difficult to determine whether President Trump's advertisement was merely a product of his temperament or whether, on the contrary, it contained a real intention to use the armed forces in the unrest sweeping the country, in a decision that has not occurred since 1992. In any case, the President, and those advising him, must assess the damage that could be done to civil-military relations and, therefore, to the American democratic system. This is without forgetting, moreover, the responsibility that rests on America's shoulders in the face of the reality that a part of humanity looks to the country as a reference letter and model to imitate.

Looking beyond Kashmir: Past and present territorial disputes between Pakistan, India and Bangladesh

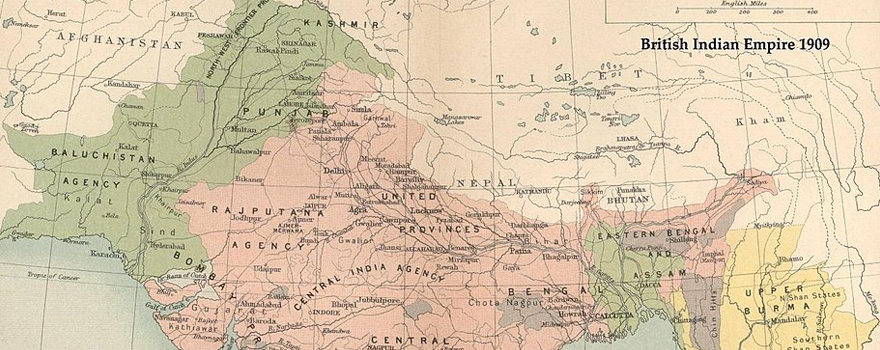

▲ The British Raj in 1909 showing Muslim majority areas in green

ESSAY / Victoria Paternina and Claudia Plasencia

Pakistan's partition from India in 1947 marked the beginning of a long road of various territorial disputes, causing different effects in the region. The geopolitics of Pakistan with India are often linked when considering their shared history; and in fact, it makes sense if we take the perspective of Kashmir as the prominent issue that Islamabad has to deal with. However, neither the history nor the present of Pakistan can be reduced to New Delhi and their common regional conflict over the Line of Control that divides Kashmir.

The turbulent and mistrustful relations between India and Pakistan go beyond Kashmir, with the region of Punjab divided in two sides and no common ground between New Delhi and Islamabad. In the same way, the bitter ties between Islamabad and a third country are not exclusively with India. Once part of Pakistan, Bangladesh has a deeply rooted hatred relationship with Islamabad since their split in 1971. Looking beyond Kashmir, Punjab and Bangladesh show a distinct aspect of the territorial disputes of the past and present-day Pakistan. Islamabad has a say in these issues that seem to go unnoticed due to the fact that they stand in the shadow of Kashmir.

This essay tries to shed light on other events that have a solid weight on Pakistan's geopolitics as well as to make clear that the country is worthy of attention not only from New Delhi's perspective but also from their own Pakistani view. In that way, this paper is divided in two different topics that we believe are important in order to understand Pakistan and its role in the region. Punjab and Bangladesh: the two shoved under the rug by Kashmir.

Punjab

The tale of territorial disputes is rooted deeply in Pakistan and Indian relations; the common mistake is to believe that New Delhi and Islamabad only fight over Kashmir. If the longstanding dispute over Kashmir has raised the independence claims of its citizens, Punjab is not far from that. On the edge of the partition, Punjab was another region in which territorial lines were difficult to apply. They finally decided to divide the territory in two sides; the western for Pakistan and the eastern for India. However, this issue automatically brought problems since the majority of Punjabis were neither Hindus nor Muslims but rather Sikhs. Currently, the division of Punjab is still in force. Despite the situation in Pakistan Punjab remains calm due to the lack of Sikhs as most of them left the territory or died in the partition. The context in India Punjab is completely different as riots and violence are common in the eastern side due to the wide majority of Sikhs that find no common ground with Hindus and believe that India has occupied its territory. Independence claims have been strengthened throughout the years on many occasions, supported by the Pakistani ISI in order to destabilize India. Furthermore, the rise of the nationalist Indian movement is worsening the situation for Punjabis who are realizing how their rights are getting marginalized in the eyes of Modi's government.