Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label brazil .

The success of several reforms is overshadowed by the impulsiveness and personal interests of a president with a tarnished image.

![Jair Bolsonaro talks to the press at the beginning of January at the headquarters of the Ministry of Economics [Isac Nóbrega, PR]. Jair Bolsonaro talks to the press at the beginning of January at the headquarters of the Ministry of Economics [Isac Nóbrega, PR].](/documents/10174/16849987/bolsonaro-2-blog.jpg)

Jair Bolsonaro talks to the press at the beginning of January at the headquarters of the Ministry of Economics [Isac Nóbrega, PR].

ANALYSIS / Túlio Dias de Assis

One year ago, on 1 January 2019, a former Brazilian army captain, Jair Bolsonaro, climbed the steps of the Palácio do Planalto for the inauguration of his presidential mandate. He was the most controversial leader to assume Brazil's head of state and government since the presidency of the no less flamboyant populist Jânio Quadros in the 1960s. The more doomsdayers predicted the imminent end of the world's fourth largest democracy; the more deluded, that Brazil would take off and take its rightful place in the international arena. As was to be expected, neither extreme was right: Brazil continues to maintain the level of democracy of the last 30 years, without any military attempt , as some had feared; nor has Brazil become the world power that many Brazilians believe it deserves because of its exceptional territorial, population, cultural and political characteristics. As is often the case, the reality has been less simple than expected.

Economy

Among the most attractive aspects of Bolsonaro's candidacy to the public during the election campaign was the promise of economic recovery under the administration of Chicago Boy minister Paulo Guedes. In order to fulfil this promise purpose, right at the beginning of his mandate, Bolsonaro unified the former ministries of Finance, Planning, development and management, Industry, work and Foreign Trade and Services under the umbrella of the Ministry of Economics, all under the command of the liberal Guedes. Guedes became a sort of "super-minister" manager of the new government's entire economic diary .

From the outset, Guedes made it clear that he would do his utmost to lift the barriers of Brazilian trade protectionism, a doctrine adopted at Degree by every government for more than half a century. In order to deploy his crusade against statism and protectionism, Guedes has this year promoted bilateral trade rapprochement with several strategic allies, which, 'unlike previous governments, will not be chosen on the basis of ideological criteria', according to Bolsonaro. Already in January there was the advertisement of a Novo Brasil at the World Economic Forum in Davos, defined by greater openness, zero tolerance for corruption and the strengthening of Latin America as a regional bloc.

Retail

Despite his support for economic openness, Bolsonaro's team has never been overly favourable to trade with Mercosur - his regional multilateral trade bloc - with Guedes even stating that it was a burden for Brazil, as he considered it an ideological rather than an economic alliance. However, this aversion to Mercosur, and mainly to Argentina, seems to have ended after the signature of the Mercosur-EU tradeagreement , given that the potential volume of trade that would be generated by such a pact would be enormously beneficial for Brazilian agricultural and livestock producers. area Similarly, a agreement was also signed with the countries of the European Free Trade Area (EFTA), comprising Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein.

Of these two agreements, the most controversial has been the one signed with the European Union, mainly due to the high levels of rejection in some member states such as France, Ireland and Austria, as it is seen as a possible risk to the Common Agricultural Policy. On the other hand, some other countries were critical, citing Bolsonaro's environmental policy, as the agreement was signed during the summer, which coincided with the time of the fires in the Amazon. As a result, several member states have still not ratified the treaty and the Austrian parliament has voted against it.

However, the fact that multilateral trade relations do not seem to have made much progress, due to the obstacles imposed by Europe, has not prevented Brazil from expanding its commercial activity. Contrary to what one might think, due to its ideological closeness to Donald Trump and his foreign policy, the rapprochement in subject economic relations has not been with the US, but with the antagonistic Asian giant. In this process, Bolsonaro's trip to Beijing stands out, where he showed himself to be open to Chinese trade, despite his previous less favourable statements in this regard. agreement During the proposal visit a free trade agreement with China, which has yet to be approved by the Mercosur summit, and several smaller agreements, including one on agricultural trade, came up.

This sudden Chinese interest in increasing agricultural imports from Brazil is due to the increase in demand for meat in China, triggered mainly by the swine fever epidemic that devastated domestic production. This has led to an immediate rise in the price of beef and pork in Brazil, up to 30% in some cuts in little more than a month, which has distorted the domestic market, as meat, mainly beef, is usually very present in the average Brazilian's regular per diem expenses .

Public accounts

With regard to the country's internal accounts, it is worth highlighting the approval of the pension reform(Reforma da Previdência), which initially had a markedly liberal character, with the aim of eliminating privileges and disproportionate pensions for high-level public officials. However, several modifications during its passage through the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate meant that the savings for the public treasury were slightly less than Guedes had envisaged. Still, it is a big step forward considering that the pension system had a deficit of 195 billion reais (about $47 billion) in 2018. This deficit is due to the fact that Brazil had one of the highest benefit systems in the world with the fewest demands, with many people retiring at the age of 55 on 70 per cent of their original salary.

This measure, together with several other adjustments in the public accounts, including the freezing of some ministerial expenditures, reduced the public deficit by 138.218 billion dollars in January (6.67% of GDP) to 97.68 billion dollars in November (5.91% of GDP), the most leave since the economic recession began five years ago. Among other relevant data is the drop in the Central Bank's base interest rate to a historic low of 4.5%, while the unemployment rate fell from 12% to 11.2%.

result As a result, Brazil's GDP has increased by 1.1 per cent, a timid but promising figure considering the huge recession from which Brazil has just emerged. Growth forecasts for 2020 vary between 2.3 and 3 per cent of GDP, depending on the approval of the long-awaited tax reforms and management assistant.

Security

Another reason for the controversial captain of reservation to become president was Brazil's historic crime problem. Just as Bolsonaro came up with a strong name to tackle the economic status , for security he recruited Sergio Moro, a former federal judge known for his indispensable role in Operação Lava Jato, Brazil's biggest anti-corruption operation, which led to the imprisonment of former president Lula himself. With the goal to fight corruption, reduce criminality and dynamite the power of organised crime, Moro was put in charge of a merger of Departments, the new Ministry of Justice and Public Security.

In general, the result has been quite positive, with a B decrease of issue in violent crime. Thus, there has been a 22% reduction in homicides, which is one of the most worrying indicators in Brazil, as it is the country with the highest absolute issue number of homicides in the world per year.

Among the factors that explain this drop in violent crime, the main one is the greater integration between the different institutions of state security forces (federal, state and municipal). The transfer of gang leaders to prisons with a higher level of isolation, thus preventing them from communicating with other members of organised crime, has also played a role. Another element has been the recent"anti-crime pack" C , which consists of a series of laws and reforms to the penal code to give more power to state security forces, as well as stiffer penalties for violent crime, organised crime and corruption.

In contrast to these developments, there has also been an increase in the number of accidental deaths in police operations. Some cases have been echoed in public opinion, such as that of an artist who ended up shot in his car when the police mistook him for a drug trafficker, or those of children killed by stray bullets in shoot-outs between drug gangs and the security forces. This, together with controversial statements by the head of state on the issue, has fuelled criticism from most of civil service examination and several human rights NGOs.

Social policy and infrastructure

In terms of social policies, the past year has been far from the apocalyptic dystopia that was expected (due to Bolsonaro's previous attitude towards homosexuals, Afro-Brazilians and women), although it has not been as remarkable as in the previously mentioned sections. There has been no progress in areas core topic, but neither have there been notable changes in terms of social policy compared to 2018. For example, the emblematic social programme Bolsa Família, created during the Lula government and which greatly helped to reduce extreme poverty, has not been cancelled.

Starting with Education, at the end of 2019 Brazil came out with one of the lowest report PISA scores, a fact that the minister of education, Abraham Weintraub, blamed on the "Education progressive Marxist mood of previous administrations". As result of the failure of the regular public system, and even the lack of security of some centres, the government has openly promoted the construction of new civic-military Education centres by state governments. In such a subject centre, students receive a Education based on military values while the officers themselves provide protection in these public spaces. It should be noted that the existing schools are among the highest ranked in Brazil on subject in terms of educational quality. However, this is not without controversy, as there are many who consider that this is not an adequate solution, as it may end up educating from a militaristic perspective.

On subject health, the most notable event this year was the end of the health cooperation programme with Cuba, Mais Médicos. goal This agreement was launched in 2013, during Dilma Rousseff's term in office, and its aim was to provide a larger and more extensive universal medical service attendance through the contracting of several doctors 'exported' by the Castro government. The programme was criticised because the Cuban doctors only received 25% of the salary provided by the Brazilian government and the remaining 75% was retained by Havana. Bolsonaro broke the agreement, thus causing vacancies in staff health care that could be filled in a short time. Cuban professionals were given the opportunity to remain in Brazil under political asylum if they revalidated their degree program in medicine in the Brazilian system. This incident has not brought about a significant change in the precarious national health system; the only consequence has been the deterioration of relations with Cuba.

Despite not making much progress on the social front, the Bolsonaro administration has made improvements in national logistics infrastructure. Under the command of the military's Tarcisio Gomes de Freitas, the Ministry of Infrastructure has stood out for its ability to complete works not finished by previous governments. This led to a noticeable difference in the issue and quality of operational roads, railways and airports compared to the previous year. Among the sources of financing for new works is the reopening of a pooled fund established in 2017 between Brazilian and Chinese financial institutions, worth US$100 billion.

![visit Bolsonaro with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during an official visit to New Delhi in late January [Alan Santos, PR] [Alan Santos, PR]. visit Bolsonaro with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during an official visit to New Delhi in late January [Alan Santos, PR] [Alan Santos, PR].](/documents/10174/16849987/bolsonaro-blog-2.jpg)

visit Bolsonaro with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during an official visit to New Delhi in late January [Alan Santos, PR] [Alan Santos, PR].

Environment

One of the areas most feared to be harmed by Jair Bolsonaro's administration was environmental policy. This concern was heightened by the controversial fires in the Amazon during July and August. To begin with, the Ministry of the Environment, like all the others, was affected by the austerity policies of Paulo Guedes, in order to balance the public accounts, although according to Minister Ricardo Salles himself, it was the one that suffered the least from the budget cuts. As a result, forest protection was compromised at the beginning of the drought period in the Amazon.

Seeing the 278% increase in deforestation in July, Bolsonaro reacted impulsively and fired the director of the high school Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciales (INPE), accusing him of favouring civil service examination and conspiring against him. The status prompted the departure from the Amazon Protection Fund of Germany and Norway, the two largest contributors, which was met with criticism from Bolsonaro, who also accused the NGOs of being the cause of the fires. Finally, under international pressure, Bolsonaro finally reacted and decided to send in the army to fight the flames. goal which he achieved in just under a month, reaching the highest number on record in October leave .

In the end, the annual total ended up 30% higher than the previous year's figure, but still within the average range of the last two decades. However, the damage to the national image was already done. Bolsonaro, thanks to his rivalry with the media, his vehement eagerness to defend "national sovereignty" and his lack of restraint when speaking, had managed to be seen as the culprit of a distorted catastrophe.

Additionally, at the end of the year, yet another controversy hit the Bolsonaro administration: the mysterious oil spill off Brazil's northeast coast. Thousands of kilometres of beaches were affected and to this day there is still no official culprit for the crime. There were several hypotheses on the matter; the most widely accepted, which was also supported by the government, was that the spill came from an illegal shipment of Venezuelan oil attempting to circumvent the trade blockade imposed on Maduro's regime. According to analyses carried out by the Universidade da Bahia, the structure of the oil was indeed very similar to that of crude oil from Venezuelan fields.

Foreign policy

In foreign policy Bolsonaro can distinguish himself rhetorically from his predecessors, but not in terms of his actions. Although he would like to apply his ideology in this area, he himself has accepted that this is not possible. In the face of the strength and interests of state institutions, such as the diplomatic tradition of Itamaraty (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Brazilian foreign policy has remained as pragmatic and neutral as in all previous democratic governments, thus avoiding the closing of doors for ideological reasons.

A good example of Brazilian pragmatism is the economic rapprochement with China, despite Bolsonaro's rejection of communist ideology. This does not mean, however, that he has distanced himself from his quasi-natural ally in terms of ideology, Donald Trump. However, the relationship with the US has been of a different nature, as there has been greater proximity in international cooperation and security. The US pushed for Brazil's designation as a strategic NATO partner , reached a agreement for the use of the Alcântara space base, very close to the Equator, and supports Brazil's entrance in the OECD.

In the economic sphere, however, there does not seem to be such closeness, and there have even been some frictions. One of these was Trump's threat to impose tariffs on steel and aluminium from Brazil and Argentina, which he finally withdrew, although the damage to trade relations and the São Paulo and Buenos Aires stock markets had already been done. Some analysts even suggest that the lack of reciprocity from the US on subject , as well as the rejection by some EU members of the agreement with Mercosur, was what pushed Bolsonaro to seek a compensatory relationship with the BRICS, whose 2019 summit took place in Brasilia.

Another peculiar point of Bolsonaro's foreign policy has been his position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which once again sample shows the inconsistency between rhetoric and action. During the election campaign Bolsonaro promised on several occasions to move the Brazilian embassy from Tel-Aviv to Jerusalem, something that has so far not happened and only an economic office has been relocated. Bolsonaro probably feared trade reprisals from Arab countries, to which Brazil exports products, mostly meat, worth almost 12 billion dollars. Prudence on this issue even earned him the signature of several agreements with Persian Gulf countries.

Despite the above, there has been one aspect of foreign policy in which Bolsonaro has managed to impose his ideology against the 'historical pragmatism' of the Itamaraty, and that is the Latin American sphere. Brazil ceased to be the theoretically neutral giant that timidly supported the so-called Socialism of the 21st century during the Lula and Dilma governments, and now coordinates with the governments of the other political side.

Most notable is his enmity with Nicolás Maduro, as well as with former president Evo Morales, whose request to pass through Brazilian territory was openly denied by Bolsonaro. There has also been a distancing from the returning Peronism in Argentina, with the absence of Bolsonaro and any high-ranking Brazilian representative at the inauguration ceremony of Kirchner's Alberto Fernández. In the same context are the approaches to Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay and Colombia, as well as the new Bolivian government provisional , with which Bolsonaro sees more similarities. With them he has promoted the creation of PROSUR as opposed to the former UNASUR controlled by the Bolivarian left. Even so, despite having adopted a more ideological policy in the region, Brazil continues to maintain diplomatic cordiality since, although its leader takes liberal conservatism to extremes in his rhetoric, his policies in the region hardly differ from those of other right-wing governments.

Bolsonaro

In general, as has been shown, Bolsonaro's government has achieved positive results in its first year, mainly highlighting its progress in the areas of security and Economics. However, while the work of various ministers has improved perceptions of the administration, Bolsonaro himself does not appear to be making a particularly positive contribution. Throughout the year, he has generated controversy over unimportant issues, which has accentuated his previous enmity with most of the press.

As a result, the president's public image has gradually deteriorated. At the end of 2019 his popularity stood at 30%, compared to the 57.5% he started the year with. This contrasts with the approval rating of members of his government, especially Sergio Moro, who has managed to remain unmoved above 50%. In addition, his son Flavio, who is a senator, has come under investigation for a possible corruption case, in a process that the president has sought to prevent. Bolsonaro also caused a scandal in the middle of the year when he tried to appoint his son Eduardo as ambassador to Washington and was accused of nepotism. In addition to the tensions in his own party, which led to a split, there is little rapport between Bolsonaro and the presidents of both chambers of the fractured congress Nacional, both of whom are under investigation in conveniently stalled anti-corruption operations.

Impeachment?

All this chaos caused by the president gives the impression of a Bolsonaro who goes against the tide of his own government. The apparent success of the reforms already carried out ends up being tainted by the impulsiveness and personal interests of the man who once defended the impersonality of the state, which ends up causing the deterioration of his political image. In addition, there is the recent release of former president Lula, which entails the risk of the unification of the civil service examination, depending on how moderate speech is adopted. This being the case, it is possible that Bolsonaro's headless but efficient government will not find it easy to stay in power until the end of its term. It should be remembered that the hand of Brazil's congress does not usually tremble when it comes to impeachments; in little more than three decades there have already been two.

The possibility that Bolsonaro's government may seek to label the Landless Movement as terrorists for forcibly occupying farms reopens a historic controversy.

When Brazil passed its first anti-terrorism legislation around the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, the initiative was seen as an example to be followed by other Latin American countries, until then generally unfamiliar with a phenomenon that since 9/11 had become pre-eminent in many other parts of the world. However, the possibility that, with the political momentum of Jair Bolsonaro, some social movement, such as the Landless Movement, may be labeled as terrorist, revives old fears of the Brazilian left and accentuates social polarization.

Flag of the Movimento Dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST)

article / Túlio Dias de Assis

At the last Berlin Film Festival, the famous Brazilian actor and filmmaker Wagner Moura presented a somewhat controversial film, "Marighella". The film portrays the life of a character from recent Brazilian history, loved by some and hated by others: Carlos Marighella, leader of the Ação Libertadora Nacional. This organization was a revolutionary guerrilla manager of several attacks against the military dictatorial regime that ruled Brazil between 1964 and 1985. For this reason, the film provoked very different reactions: for some, it is the just exaltation of an authentic martyr of the anti-fascist struggle; for others, it is an apology of armed guerrilla terrorism. This small ideological dispute about "Marighella", although it may seem insignificant, is the reflection of an old wound in Brazilian politics that is reopened every time the country discussion on the need for anti-terrorist legislation.

The concept of anti-terrorism legislation is something that has taken hold in many parts of the world, especially in the West after 9/11. However, this notion is not so common in Latin America, probably due to the infrequency of attacks of this type subject suffered by the region. However, the lack of attacks does not imply that there is no presence of such movements in American countries; in fact, several of them are known to be a "refuge" for such organizations, as is the case in the Triple Frontier, the contact area between the borders of Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay. What happens in that area is largely due to the lack of direct and effective legislation against organized terrorism by national governments.

In the case of Brazil, as in some of its neighboring countries, the lack of anti-terrorism legislation is due to the historical fear on the part of leftist parties of its possible use against social movements of a certain aggressive nature. In Brazil, this was already reflected in the political transition of the late 1980s, when there was a clear protest by the PT(Partido dos Trabalhadores), then under the leadership of Luiz Inácio "Lula" da Silva, against any attempt to introduce the anti-terrorist concept into legislation. Curiously, the 1988 Federal Constitution itself mentions the word "terrorism" twice: first, as something to be rejected in Brazilian foreign policy, and second, as one of the unforgivable crimes against the Federation. In spite of this, no attempt to define this crime was successful, and although after the 9/11 attacks discussions about a possible law were resumed, the Labor left - already during Lula's presidency - continued to justify its refusal by invoking the persecution carried out by the dictatorship's board Militar. See that the same former president Dilma Rousseff was imprisoned for being part of the VAR-Palmares(Vanguarda Armada Revolucionária Palmares), an extreme left-wing revolutionary group that was part of the armed civil service examination to the regime.

Terrorist threat at the Olympic Games

During the PT's terms of office (2003-2016) there was no subject legislative initiative by the Government on topic; moreover, any other project arising from the Legislature, whether the Senate or the Chamber of Deputies, was blocked by the Executive. Often the Government also justified its position by alluding to a supposed "neutrality", hiding behind the desire not to get involved in external conflicts. This attitude would lead to several fugitives accused of participating or collaborating in attacks in other countries taking refuge in Brazil. However, in mid-2015, as the start of the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro approached, the risk of a possible attack in the face of such an important event was assessed. This, together with pressure from the right wing at congress (bear in mind that Rousseff won the 2014 elections with a very narrow margin of less than 1%), led the Petista government to ask the parliament to draft a concise definition of terrorism and other related crimes, such as those related to financing. Finally, the first Brazilian anti-terrorism law was signed by Rousseff in March 2016. Although this is the "official" version of that process, there are not few who defend that the real reason for the implementation of the law was the pressure exerted by the FATF (group Financial Action Task Force against Money Laundering, created by the G8), since this entity had threatened to include Brazil in the list of non-cooperative countries against terrorism.

The Brazilian anti-terrorism law was effective, as it served as the legal framework for the so-called Operação Hardware. Through this operation, the Brazilian Federal Police managed to arrest several suspects of a DAESH branch operating in Brazil, who were planning to carry out an attack during the Rio Olympics. Federal Judge Marcos Josegrei da Silva convicted eight suspects for membership to an Islamic terrorist group , in the first sentence of this kind subject in the history of Brazil. The judge's decision was quite controversial at the time, largely due to Brazilian society's unfamiliarity with this subject risky . As a result, many Brazilians, including part of the press, criticized the "disproportionality" with which the defendants were treated.

Bolsonarist Momentum

Since then, Brazil has come to be considered as a sort of example among South American countries in the fight against terrorism. However, it does not seem that the status quo maintained during the end of the Rousseff administration and the short term of Temer will remain intact for long. This is due to the fiery discussion stirred up by the Bolsonarista right wing, which advocates for the criminal activities of several far-left groups, especially the MST(Movimento Dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra) to be classified as terrorism. The MST is the largest agrarian social movement, Marxist in nature, and is known nationally for its occupations of lands that the group considers "useless or underutilized" in order to "put them to better use". The ineffectiveness of the State in stopping the invasions of private property carried out by the MST has been recurrently denounced in the congress, especially during the PT government years, without major consequences. However, now that the right wing has greater weight, the discussion has come back to life and not a few deputies have already mentioned their intention to seek to denounce the Landless Movement as a terrorist organization. Bolsonaro himself has been a fierce advocate of outlawing the MST.

Also, at the same time that the current Minister of Justice, Sergio Moro, announces the possibility of the creation of an anti-terrorist intelligence system, following the model of his American counterpart, and the congress discussion the expansion of the current list of terrorist organizations to include groups such as Hezbollah, other Brazilian politicians have decided to launch in the Senate a proposal legislation to criminalize the actions of the MST. If approved, this initiative would make real the fear that the left has invoked all these years. After all, this is not the best way to fulfill the promise of "governing for all". Moreover, such a disproportionate measure for this subject of activities would only increase the already intense political polarization present today in Brazilian society: it would be tantamount to rubbing salt in an old wound, one that seemed to be about to heal.

Limiting attention with China and controlling the arrival of Venezuelan refugees, among the measures promoted by the winner in the first round.

With a support of more than 46% of the voters, the right-wing Jair Bolsonaro won a wide victory in the presidential elections of October 7, which will nevertheless require a second round at the end of the month. His direct opponent, Fernando Haddad, of the Workers' Party, barely reached 29% of the votes, which complicates that in three weeks the correlation of forces could be turned around. A Bolsonaro presidency, therefore, is possible, and this makes it advisable to examine what foreign policy the new stage will bring.

▲ Jair Bolsonaro, at an electoral campaign rally [PSL].

article / Túlio Dias de Assis

One of the best known sayings Brazilians have about their own country is that "O Brasil não é um país para principiantes" (Brazil is not a country for beginners ). Of course, such a saying would be very apt when describing the country's current status . The Latin American giant is reeling from the instability caused by a truly unprecedented electoral campaign and the possibility of the victory of a divisive candidate .

The electoral campaign has been anything but "conventional", with one candidate trying to promote the vote from his cell in the federal prison of Curitiba, in Paraná, and another being stabbed in plenary session of the Executive Council political act in the streets of Juíz de Fora, in Minas Gerais. The first, former president Luís Inácio "Lula" da Silva, finally had to cede the post to another leader of his party, Fernando Haddad, due to his criminal status ; the second, Jair Bolsonaro, was favored electorally by the stabbing and the greater dispersion of the vote due to the forced withdrawal of Lula.

The elections had a motley group of candidates representing the most disparate types of ideologies. In this Sunday's vote, as predicted by the polls, the race was reduced to two presidential candidates, located at the antipodes of the political spectrum: Bolsonaro and Haddad, candidates of the Social Liberal Party (PSL) and the Workers' Party (PT), respectively.

Thus, Bolsonaro obtained more than 46% of the votes, far exceeding the polls' forecasts, while Haddad received the support of 29% of the voters. As neither candidate surpassed 50% of the votes on October 7, the two most voted presidential candidates will go to a second round, which will take place on October 28.

Jair Messias Bolsonaro, the "Brazilian Trump".

Bolsonaro is undoubtedly the biggest surprise of these elections, since his positions, very reactionary in some issues, are completely out of the mostly socialist political spectrum to which Brazil had become accustomed since the beginning of the century. He is a military man in the reservation who for the last decades served as federal deputy for the state of Rio de Janeiro. During his work in the Chamber leave, many of his statements, often homophobic, racist and sexist, went viral. Much of the Brazilian press has labeled him as extreme right-wing and has carried out a harsh campaign against him, similar to what happened with Donald Trump in the USA.

The controversy has benefited Bolsonaro, expanding his electoral base. After the attack in Minas Gerais, he saw his popularity increase(rising in the polls from 22% to 32%) and somewhat mitigating the rejection he provokes among part of the population.

On domestic political issues, the PSL's candidate is characterized by controversial statements in favor of the revocation of the disarmament statute (issued during the Lula administration), a reduction of the state bureaucratic apparatus, the liberalization of the Economics, the privatization of public companies and agencies, the reduction of the age of criminal majority, the establishment of higher and harsher penalties for serious crimes and the militarization of the police in their confrontations against the criminal gangs dominant in the favelas. In addition, it flatly rejects, among other issues, gender ideology, gender and racial quotas -in all subject of public agencies- and political movements of Marxist ideology.

Foreign policy. In terms of international policy, Bolsonaro has mentioned that he intends to strengthen Brazil's relations with the US -given his sympathy towards President Trump's policies-, the EU and democratic countries in Latin America; while he has radically positioned himself against rapprochement with countries with dictatorial regimes, among which he has included China, Venezuela, Bolivia and Cuba. He defends Israel's policies and has promised to move the Brazilian embassy to Jerusalem, as President Trump did almost a year ago. Finally, he rejects the uncontrolled flow of Venezuelan immigrants entering Brazil through the state of Roraima, and has warned that he would take drastic measures to control it, since the number of migrants from Venezuela already exceeds 50,000.

Fernando Haddad, the heir of Lula's bequest

Haddad has been mayor of the city of São Paulo and minister of Education during Lula's government. He initially opted for the post of vice-president, accompanying Lula in the PT candidacy. But when Lula saw his options closed final by the Supreme Electoral Court, as he was imprisoned under a 12-year sentence for corruption, he designated Haddad as presidential candidate, well into the electoral campaign.

Before the annulment of his candidacy, Lula was clearly leading in the polls and could even win in the first ballot. This support was mainly among the population that benefited from his highly successful socialist policies during his two terms in office (2003-2006 and 2007-2010), including the Fome Zero (Zero Hunger) program, which aimed to end hunger in Brazil; Primeiro Emprego (First employment), a program focused on eliminating youth unemployment; and the better known Bolsa Família, a continuation of Fome Zero in the form of family benefits, which successfully lifted several million Brazilians out of poverty.

This social success, which mainly affected the North and Northeast regions of Brazil, where there is a larger population below the poverty line, gave the PT a solid electoral base, although linked to Lula's leadership. With the change of candidate, the PT's popularity declined and its voting intentions were distributed among the other presidential candidates. As candidate, Lula surpassed 37% in the first polls; however, Haddad did not reach 30% in the first round.

Foreign policy. The PT is a left-wing party that is quite aligned with the Latin American political doctrine of the so-called Socialism of the 21st Century. Its program in international politics is to maintain good relations with the members of the BRICS -especially the cooperation with China- and MERCOSUR, and to continue actively participating in the UN, specifically in bodies such as the committee of Human Rights (HRC) or the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), today presided over by Lula's former minister manager of the Fome Zero program, José Graziano da Silva. Haddad has not taken a specific position on the Venezuelan regime, unlike Bolsonaro; however, he has mentioned the need to help in the mediation for the resolution of internal conflicts in the neighboring country, without condemning the Chavista government at any time.

Second round

The Brazilian scenario is undoubtedly very peculiar and there is an awareness that these elections could define the course of the tropical giant for some time to come. Bolsonaro starts with a decisive advantage for the second round on October 28. Haddad will probably be able to count on the support of several of the trailing candidates, such as Ciro Gomes, from PDT, or Marina Silva, from REDE (both former ministers of Lula's government), due to the radical difference of Bolsonaro's policies with the "conventional" candidates.

The possibility of a final victory of the military man in the reservation may mobilize part of the electorate, increasing the participation among those who want to prevent his entrance in Brasília. The vote of fear of Bolsonaro that the PT will promote and the "normality" with which the controversial candidate will want to accentuate his candidacy will decide this final stretch.

The constant expansion of the crop in Mercosur countries has led them to exceed 50% of world production.

Soybean is the agricultural product with the highest commercial growth in the world. The needs of China and India, major consumers of the fruit of this oleaginous plant and its derivatives, make South America a strategic granary. Its profitability has encouraged the extension of the crop, especially in Brazil and Argentina, but also in Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay. Its expansion is behind recent deforestation in the Amazon and the Gran Chaco. After hydrocarbons and minerals, soybeans are the other major commodity in South America subject .

article / Daniel Andrés Llonch [English version].

Soybean has been cultivated in Asian civilizations for thousands of years; today its cultivation is also widespread in other parts of the world. It has become the most important oilseed grain for human consumption and animal feed. With great nutritional properties due to its high protein content, soybeans are marketed both in grain and in their oil and meal derivatives.

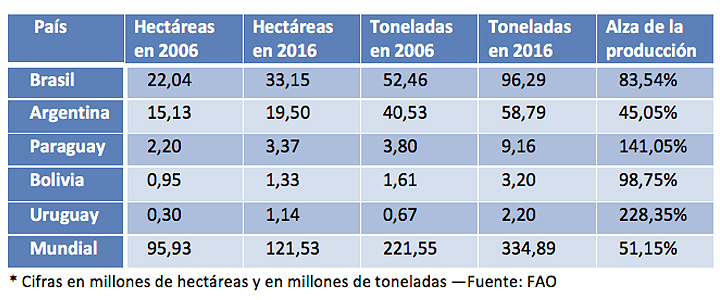

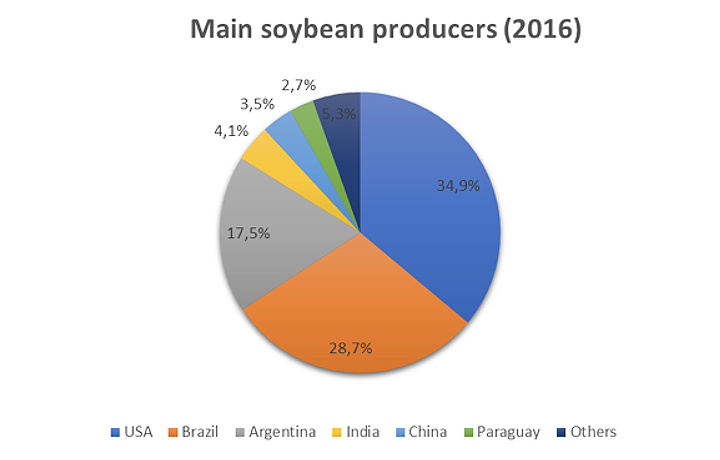

Of the eleven largest soybean producers, five are in South America: Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay. In 2016, these countries were the origin of 50.6% of world production, whose total reached 334.8 million tons, according to FAO's data . The first producer was the United States (34.9% of world production), followed by Brazil (28.7%) and Argentina (17.5%). India and China follow on the list, although what is significant about the latter country is its large consumption, which in 2016 forced it to import 83.2 million tons. A large part of these import needs are covered from South America. South American production is centered in the Mercosur nations (in addition to Brazil and Argentina, also Paraguay and Uruguay) and Bolivia.

Strong international demand and the high relative profitability of soybeans in recent years have fueled the expansion of soybean cultivation in the Mercosur region. The commodity price boom, in which soybeans also participated, led to profits that were directed to the acquisition of new land and equipment, allowing producers to increase their scale and efficiency.

In Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay, the area planted with soybean is the majority (it constitutes more than 50% of the total area planted with the five most important crops in each country). If to group we add Uruguay, where soybean has enjoyed a later expansion, we have that the production of these five South American countries has gone from 99 million tons in 2006 to 169.7 million in 2016, which is an increase of 71.2% (Brazil and Bolivia have almost doubled their production, somewhat surpassed by Paraguay and Uruguay, a country where it has tripled). In the decade, this South American area has gone from contributing 44.7% of world production to total 50.6%. In that time, the cultivated area increased from 40.6 million hectares to 58.4 million hectares.

|

Countries

As the second largest soybean producer in the world, Brazil reached in 2016 a production of 96.2 million tons (28.7% of the world total), with a crop area of 33.1 million hectares. Its production has known a constant increase, so that in the last decade the volume of the crop has increased by 83.5%. The jump has been especially B in the last four years, in which Brazil and Argentina have experienced the highest rate of increase of the crop, with an annual average of 936,000 and 878,000 hectares, respectively, from agreement with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) department .

Argentina is the second largest producer in Mercosur, with 58.7 million tons (17.5% of world production) and a cultivated area of 19.5 million hectares. Soybean began to be planted in Argentina in the mid 1970s, and in less than 40 years it has made unprecedented progress. This crop occupies 63% of the country's areas planted with the five most important crops, compared to 28% of the area occupied by corn and wheat.

Paraguay, meanwhile, had a 2016 harvest of 9.1 million tons of soybeans (2.7% of world production). In recent seasons, soybean production has increased as more land is allocated for its cultivation. From agreement with the USDA, over the last two decades, land devoted to soybean cultivation has steadily increased by 6% annually. There are currently 3.3 million hectares of land in Paraguay dedicated to this activity, which constitutes 66% of the land used for the main crops.

In Bolivia, soybeans are grown mainly in the Santa Cruz region. According to the USDA, it accounts for 3% of the country's Gross Domestic Product, and employs 45,000 workers directly. In 2016, the country harvested 3.2 million tons (0.9% of world production), on an area of 1.3 million hectares.

Soybean plantations occupy more than 60 percent of the arable land in Uruguay, where soybean production has been increasing in recent years. In fact, it is the country where production has grown the most in relative terms in the last decade (67.7%), reaching 2.2 million tons in 2016 and a cultivated extension of 1.1 million hectares.

|

Increased demand

Soybean production represents a very important fraction of the agricultural GDP of South American nations. The five countries mentioned above, together with the United States, account for 85.6% of global production, making them the main suppliers of the growing world demand.

This production has experienced a progressive increase since its insertion in the market, with the exception of Uruguay, whose expansion of the product has been more recent. In the period between 1980 and 2005, for example, total world soybean demand expanded by 174.3 million tons, or 2.8 times. During this period, the growth rate of global demand accelerated from 3% per year in the 1980s to 5.6% per year in the last decade.

In all the South American countries mentioned above, soybean cultivation has been especially encouraged, due to the benefits it brings. Thus, in Brazil, the largest regional producer of the oleaginous grain, soybeans contribute revenues estimated at 10 billion dollars in exports, representing 14% of the total products marketed by the country. In Argentina, soybean cultivation went from representing 10.6% of agricultural production in 1980/81 to more than 50% in 2012/2013, generating significant economic benefits.

The outlook for growth in demand suggests that production will continue to rise. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that global production will exceed 500 million tons in 2050, double the volume harvested in 2010. Much of this demand will have to be met from South America.

Russia's GLONASS positioning system has placed ground stations in Brazil and Nicaragua; the Brazilian ones are accessible, but the Nicaraguan one is open to conjecture.

At a time when Russia has declared its interest in having military installations in the Caribbean again, the opening of a Russian station in Managua's area has raised some suspicions. Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, has opened four stations in Brazil, managed with transparency and easy access; in contrast, the one it has built in Nicaragua is shrouded in secrecy. The little that is known about the Nicaraguan station, strangely larger than the others, contrasts with how openly data can be collected about the Brazilian ones.

article / Jakub Hodek [English version].

It is well known that information is power. The more information one has and manages, the more power one enjoys. This approach should be taken when examining the station facilities that support the Russian satellite navigation system and their construction in close proximity to the United States. Of course, we are no longer in the Cold War period, but some traumas of those old days can perhaps help us to better understand the cautious position of the United States and the importance Russia sees in having its facilities in Brazil and especially in Nicaragua.

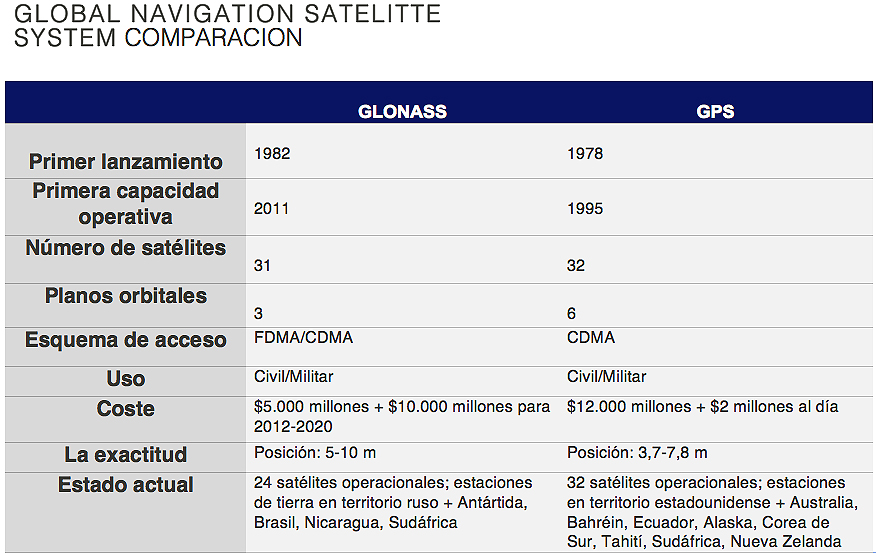

That historical background of the Cold War is at the origin of the two major navigation systems we use today. The United States launched the Global Positioning System (GPS) project in 1973, and possibly in response, the Soviet Union introduced its own positioning system (GLONASS) three years later. [1] Nearly 45 years have passed, and these two systems are no longer serving as a means for Russians and Americans to try to obtain information about the opposing side, but are collaborating and thus providing a more accurate and faster navigation system for consumers who purchase a smartphone or other electronic device. [2]

However, to achieve global coverage both systems need not only satellites, but also ground stations strategically located around the world. With that purpose, Russian Federal Space Agency Roscosmos has erected stations for the GLONASS system in Russia, Antarctica and South Africa, as well as in the Western Hemisphere: it already has four stations in Brazil and since April 2017 it has one in Nicaragua, which due to the secrecy surrounding its function has caused distrust and suspicion in the United States [3] (USA, for its part, has GPS ground stations in its territory and in Australia, Argentina, United Kingdom, Bahrain, Ecuador, South Korea, Tahiti, South Africa and New Zealand).

The Russian Global Navigation Satellite System(Globalnaya Navigatsionnaya Sputnikovaya Sputnikovaya Sistema or GLONASS) is a positioning system operated by the Russian Aerospace Defense Forces. It consists of 28 satellites, allowing real-time positioning and speed data for surface, sea and airborne objects around the world. [ 4] In principle GLONASS does not transmit any identification information staff; in fact, user devices only receive signals from the satellites, without transmitting anything back. However, it was originally developed with military applications in mind and carries encrypted signals that are supposed to provide higher resolutions to authorized military users (same the US GPS). [5]

In Brazil, there are four ground stations used to track signals from the GLONASS constellation. These stations serve as correction points in the western hemisphere and help to significantly improve the accuracy of navigation signals. Russia is in close and transparent partnership with the Brazilian space agency (AEB), promoting the research and development of the South American country's aerospace sector.

|

In 2013, the first station was installed, located at campus of the University of Brasilia, which was also the first Russian station of that subject abroad. Another station followed at the same location in 2014, and later, in 2016, a third one was placed at the high school Federal Science Education and Technology of Pernambuco, in Recife. The Russian Federal Space Agency Roscosmos built its fourth Brazilian station on the territory of the Federal University of Santa Maria, in Rio Grande do Sul. In addition to fulfilling its main purpose of increasing the accuracy and improving the performance of GLONASS, the facility can be used by Brazilian scientists to carry out other types of scientific research . [6]

The level of transparency that surrounded the construction and then prevailed in the management of the stations in Brazil is definitely not the same applied to the one opened in Managua, the capital of Nicaragua. There are several pieces of information that sow doubts regarding the real use of the station. To begin with, there is no information on the cost of the facilities or on the specialization of the staff. The fact that it has been placed a short distance from the U.S. Embassy has given rise to conjecture about its use for eavesdropping and espionage.

In addition, vague answers from representatives of Nicaragua and Roscosmos about the use of the station have failed to convey confidence about project. It is a "strategicproject " for both Nicaragua and Russia, concluded Laureano Ortega, the son of the Nicaraguan president. Both countries claim to have a very fluid and close cooperation in many spheres, such as in projects related to health and development, however none of them have materialized with such speed and dedication. [7]

Given Russia's increased military presence in Nicaragua, empowered by the agreement facilitating the docking of Russian warships in Nicaragua announced by Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu during his visit to the Central American country in February 2015, and also concretized in the donation of 50 Russian T-72B1 tanks in 2016 and the increasing movement of the Russian military staff , it can be concluded that Russia clearly sees strategic importance in its presence in Nicaragua. [ 8] [ 9] All this is viewed with suspicion from the U.S. The head of the U.S. Southern Command, Kirt Tidd, warned in April that "the Russians are pursuing an unsettling posture" in Nicaragua, which "impacts the stability of the region."

Undoubtedly, when world powers such as Russia or the United States act outside their territory, they are always guided by a combination of motivations. Strategic moves are essential in the game of world politics. For this very reason, the financial aid that a country receives or the partnership that it can establish with a great power is often subject to political conditionality. In this case, it is difficult to know for sure what exactly is the goal of the station in Nicaragua or even those in Brazil. At first glance, the goal seems neutral-offering higher quality of navigation system and providing a different option to GPS-but given the new value Russia is placing on its geopolitical capabilities, there is the possibility of a more strategic use.