Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label colombia .

The change of government and its stricter vision have slowed down the implementation of agreement, but it is making progress in its application.

The implementation of the agreement peace agreement in Colombia is proceeding more slowly than those who signed it two years ago expected, but there has not been the paralysis or even the crisis predicted by those who opposed the election of Iván Duque as president of the country. The latest estimate speaks of a compliance with the stipulations of the peace agreement agreement close to 70%, although the remaining 30% is already not being complied with.

![Colombian President Iván Duque at a public event [Efraín Herrera-Presidencia]. Colombian President Iván Duque at a public event [Efraín Herrera-Presidencia].](/documents/10174/16849987/colombia-paz-blog.jpg)

▲ Colombian President Iván Duque at a public event [Efraín Herrera-Presidencia].

article / María Gabriela Fajardo

Iván Duque arrived at the Casa de Nariño - the seat of the Colombian presidency - with the slogan "Peace with Legality", degree scroll that synthesized his commitment to implement the peace agreement , signed in November 2017, but reducing the margins of impunity that in his opinion and that of his party, the Democratic Center, existed for the former combatants of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). One year after his election as president, it is worth analyzing how the implementation of the peace agreement agreement is going.

agreement About 70% of the provisions of agreement have already been fulfilled, totally or partially, or will be fulfilled within the stipulated time, according to the estimate of high school Kroc, in charge of making the official estimate of the implementation of the peace process. According to its third report, published in April, 23% of the commitments have been completely fulfilled, 35% have reached advanced levels of implementation, and 12% are expected to be completely fulfilled by the stipulated time. However, almost 31% of the content of the agreement has not yet begun to be implemented, when it should have been underway.

The United Nations, to which the agreement grants a supervisory role, has underlined the efforts made by the new Government to activate the various instances provided for in the text. In his report to committee Security, the University Secretary of the UN, António Guterres, highlighted at the end of 2018 the launching of the Commission for the Follow-up, Promotion and Verification of the Implementation of the Final agreement (CSIVI) and of the committee National Commission for Reincorporation (CNR).

As indicated by Raúl Rosende, chief of staff of the UN Verification mission statement in Colombia, Guterres' report positively estimated that it had "obtained the approval of 20 collective projects and 29 individual projects of ex-combatants in the process of reincorporation, valued at 3.7 million dollars and which will benefit a total of 1,340 ex-combatants, including 366 women". These projects have involved the participation of the governments of Antioquia, Chocó, Cauca, goal, Santander, Sucre and Valle del Cauca, which have facilitated departmental reincorporation roundtables to coordinate local and regional efforts, thus involving Colombian civil society to a greater extent.

The UN has also expressed some concerns, shared by Colombian civil society. The main one has to do with security in some of the historical conflict zones where a high issue number of social leaders have been killed. The murders have been concentrated in Antioquia, Cauca, Caquetá, Nariño and Norte de Santander. Thus, throughout 2018 at least 226 social leaders and Human Rights defenders were killed, according to data of the high school of programs of study for development and Peace(Indepaz). The Ombudsman's Office put the figure at 164.

In addition, as Rosende has recalled, many of the indigenous communities have suffered assassinations, threats and forced displacement. This has occurred in ethnic territories of the Awá, Embera Chamí and Nasa peoples in Caldas, Cauca, Chocó, Nariño and Valle del Cauca.

Along with the successes and concerns, the UN also points to a series of challenges that lie ahead in the post-conflict period. On the one hand, there is the challenge of guaranteeing former combatants the necessary legal security, generating confidence and producing real progress in terms of social and political reintegration. Another great challenge is to achieve the autonomous and effective functioning of mechanisms core topic such as the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) and the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence and Non-Repetition or Truth Commission. In addition, there is also the social challenge to attend to the communities affected by the conflict, which demand security, Education, health, land, infrastructure and viable alternatives against illegal economies.

Controversial aspects

Issues related to the SJP have been the focus of Duque's most controversial actions. In March, the president presented formal objections to the law regulating the SJP, which he wants to modify six points of its 159 articles. Two of them refer to the extradition of former combatants, something that is not contemplated now if they collaborate with the transitional justice system, especially in the case of crimes committed after the signature of agreement. Duque also proposes a constitutional reform that excludes sexual crimes against minors from the JEP, determines the loss of all benefits if there is recidivism in a crime and transfers to the ordinary justice system the cases of illegal conducts started before the agreement and continued after. The objections were rejected in April by the House of Representatives and also by the Senate, although the validity of the result in the latter was left in question, thus lengthening the discussion.

A new controversy may arise when the Territorial Spaces of training and Reincorporation (ETCR) are to be closed in August. Around 5,000 ex-combatants are still in or around them. The High Counselor for the Post-Conflict, Emilio Archila, has stated that by that time, with the financial aid of the FARC (the political party that succeeded the guerrilla) and the Government, the ex-combatants must have work, be clear about what their residency program will be and be prepared for reincorporation into civilian life.

Within the reincorporation process, the lack of compliance by FARC leaders with their commitment, stipulated in the peace agreement agreement , to remain until the end in the ETCRs in order to contribute with their leadership to the smooth running of the process, is a cause for concern. However, in recent months, several leaders have left these territories, among them "El Paisa", who has not presented himself before the JEP, which has demanded his capture.

Nor is former ringleader Ivan Marquez cooperating with the transitional justice system, successively delaying his appearance before the JEP citing security concerns. Márquez has cited the murder of 85 former guerrillas since the signature of the peace agreement , and has accused the government of serious failures to comply.

There is also the case of Jesús Santrich, who like Márquez had acquired a seat in the congress thanks to the implementation of the peace process. Santrich has been detained since April 2018 based on an Interpol red notice at the request of the United States, which accuses him of the shipment of 10 tons of cocaine made after the signature of the agreement peace .

A topic quite addressed from the time of the negotiations has to do with forced eradication and crop spraying. The illicit crop substitution program began to yield results in 2018, resulting in thousands of peasant families agreeing with the government to replace their coca crops with other licit crops. Although in some Departments such as Guaviare there was voluntary crop eradication, this was not enough to offset the increase in plantings in 2016 and 2017. In 2018, close to 100,000 families - responsible for just over 51,000 hectares of coca - signed substitution agreements and this issue is expected to continue to increase throughout 2019. According to the Colombian government, citing figures from the U.S. State Department's department , more than 209,000 hectares of coca leaf have been planted, far more than in the era of Pablo Escobar, according to figures presented by President Iván Duque last month before the Constitutional Court.

The benefits of peace are indisputable and much remains to be done to consolidate it. It is a task that cannot be left in the hands of the Government alone, but requires the support of former combatants, their former leaders and civil society. The great challenge is to accelerate the implementation of agreement and reduce political polarization, all in the search for national reconciliation.

[Jorge Orlando Melo, Historia mínima de Colombia. El high school de México-Turner. Bogotá, 2018. 330 p.]

review / María Gabriela Fajardo

|

This history of Colombia written by Jorge Orlando Melo stands out for its evident effort of political neutrality. The processes, continuities and historical ruptures of the nation are mentioned without revealing any partisan tendency subject . The author tries to remain impartial in narrating the events that have brought Colombia to where it is today. This makes the work of Melo - born in Medellin in 1942, historian at the National University of Colombia and presidential advisor for human rights in 1990 - especially suitable for readers without a special knowledge of Colombian history, as they can judge for themselves the evolution of the creation of a nation where the State was first. This is precisely the purpose of the collection of "minimal histories" commissioned from the high school of Mexico.

A large part of the book is devoted to the colonial period, thus highlighting the importance of the historical report in the process of training of the country and in its current changes. It is not, therefore, the usual linear route through political events, but rather focuses on the cultural evolution of that report forged early and developed in successive social dynamics.

On the other hand, the role of the regions is an element core topic in the training of the colonial society, whose bequest is an inefficient central power, in a country where there are laws that seem to be negotiable, the society is divided into different social strata, the land belongs to a few and there is a constant political polarization at the hands of clientelist governments.

This happens in a Colombia in which the role of geography has been a determining factor in the processes of development of the nation. Melo speaks of isolated areas of difficult access, of very diverse subject: "islands of prosperity, security or healthiness in the middle of an ocean of poverty, violence and disease". That ocean has diminished today, but there are islands that continue to be the perfect route for drug trafficking.

The ideological struggles in Colombia have been intense: the Conservative Hegemony, of 32 years, was followed by the Liberal Hegemony, of 13; then came the era of the National Front, during which Conservatives and Liberals alternated in each period, creating an atmosphere of equilibrium and relative tranquility for a short deadline period of time. "The struggle between liberals and conservatives was, more than a political confrontation for electoral triumph, a holy war for different social models," writes Melo. However, this generated political exclusion and led to the training of groups outside the law, raised against the government and financed by drug trafficking. The confrontation made the institutional weaknesses visible and left little room for justice. Violence then became routine and ended up being Colombia's greatest historical failure, with special responsibility of those who promoted violence as an effective tool for social change.

For Melo, it is "human agency"-that is, the way in which people use their resources to adapt to circumstances-that defines history; it is men and women who, in their joint action, generate change and are the builders of their history. Unlike the most common position on Colombian history, Melo does not fall into determinism: he does not make reference letter to a culture of innate violence that naturally condemns Colombians to fight each other. On the contrary, he makes it clear that events such as April 6, Rojas Pinilla's coup d'état in 1953 or the bloody seizure of the Palace of Justice in 1985, must be seen in perspective and considered as moments of a social process.

The Colombian state did not achieve nationhood properly until the end of the 20th century, when the "dream of the creators of the nation" of having the whole territory covered by law, a single market and a political system was achieved. Colombia's unique history began with the Patria Boba, as the stage between the cry for independence and the battle of Boyacá, when the Creoles effectively achieved independence, is usually called. Since then there was a great lack of unity, manifested in an endless number of revolutions, reforms and constitutions. Colombia underwent an exhausting, exhausting and at the same time violent process aimed at achieving political, legal, economic and cultural cohesion throughout this extremely diverse country, with a geography that segmented it into regions, with varied and dispersed human groups.

But this past does not prejudge the future. The reader arrives at the end of this "Minimal History of Colombia" with the awareness of an open future for the great South American country. Colombia, once one of the most violent countries, now has a Nobel Peace Prize winner, is in a post-conflict process and has begun to be taken into account to a greater extent by the international community for its great progress.

▲Street art in the city of Medellín

ANALYSIS / María Gabriela Fajardo

Colombia experienced on March 11 the first elections held after signature in 2016 of the Peace agreement between the government and the guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). These elections to the country's bicameral congress - members of the Senate and the House of Representatives were elected - were the first occasion in which the different ideological sectors could measure their forces without the distortion of an armed struggle in significant parts of the territory. Traditionally, social rejection of the guerrilla campaign has been alluded to as an explanation for why the left in Colombia has usually enjoyed little popular support. Has the arrival of peace changed the correlation of political forces and has it led to an improvement in the electoral results of the left?

To answer these questions, we will examine the results obtained by the different political options, grouped into sections of the ideological spectrum (right, center-right, center-left and left), in the elections to congress held since the beginning of this century. An examination of the political composition of congress over the last decade and average will give perspective to the results of the March 11 legislative elections. These elections meant the integration of the FARC into the Colombian political party system, under a different name - Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común - but with the same acronym.

In the 2002-2018 period there were also, in addition to the five elections to the congress, as many presidential elections. The latter are mentioned in the analysis because they help to clarify the contexts, but they are not included in the comparative work , given that the presidential elections are governed by more personalistic dynamics and complex vote transfers take place due to the double round process. The March 11 elections, however, provide considerations for the presidential elections of May 27.

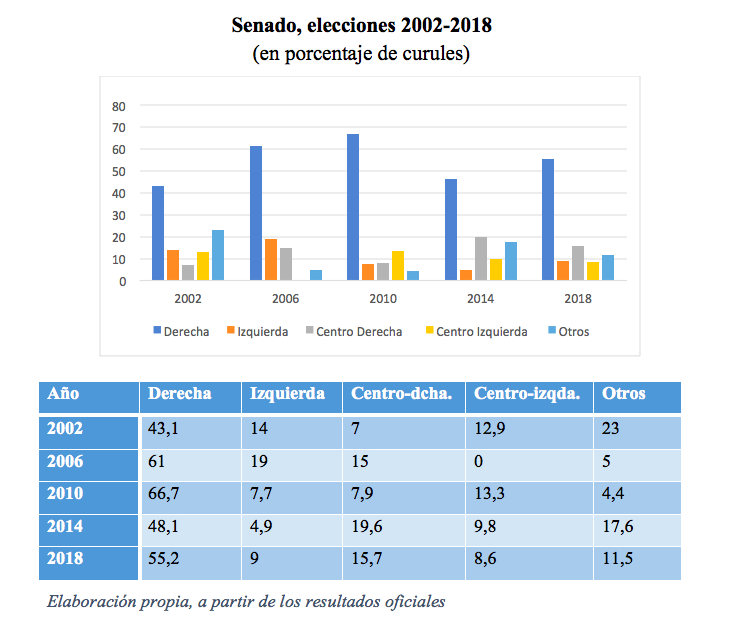

Senate

The Parapolitics scandal distorted the reception of the results of the 2002 legislative elections, after paramilitary chief Salvatore Mancuso claimed that 35% of the elected congress were "friends" of his organization. The right wing, represented by the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party, won 41.1% of the Senate seats. This figure does not include the seats won by other minor political groups, among them Colombia Siempre, whose head of list was the current candidate presidential candidate Germán Vargas Lleras. The left, on the other hand, was quite fractioned, in groups such as Vía Alterna and Movimiento Popular Unido, and obtained 14% of the Senate seats. The center-left won 12.9% and the center-right 7%.

|

In the 2002 presidential elections, held a few months after the legislative elections, Álvaro Uribe became head of state, with the vote of 53.1% of the voters. Uribe ran as an independent candidate , after splitting from the Liberal Party, and had the support of much of the right and center-right, including Cambio Radical, Somos Colombia and the Conservative Party, which then did not participate in the presidential race.

Thus, in the 2006 legislative elections, a new party, the Partido Social de Unidad Nacional (better known as Partido de la U), created by Álvaro Uribe, played a major role. The Partido de la U won the elections, obtaining 20% of the seats: for the first time neither of the two traditional parties (Liberal and Conservative) had won result . The new party was here to stay, so that the right wing was now represented by three parties (de la U, Liberal and Conservative), with 61% of the senators. The left, although it increased to 19% of the Senate seats, was split into several political parties without weight and without the possibility of proposing drastic legislative changes. The center-right, represented by Cambio Radical, was in fourth place, with 15% of seats, while the center-left obtained none.

In 2010 the right wing reached its highest point, with 66.7% of the Senate seats, a figure that includes the three right-wing parties mentioned above and MIRA, a group with a smaller presence. These were moments of political dominance for Uribismo. In the electoral months of 2010, President Uribe was expressing his support to Juan Manuel Santos as candidate presidential. It was thought that he would continue Uribe's policies of confronting the guerrillas and organizing the security forces. However, after coming to power, Santos surprised by disassociating himself from Uribe and opening negotiations with the FARC in 2012, which led to the rupture of the relationship between the two politicians (El periodico, 2017). The strength demonstrated by the right in the 2010 legislative elections was accompanied by a great weakness of the left, which obtained only 7.7% of the Senate seats and would become the perfect ally of President Santos to carry out his diary and his journey towards the political center. The center-left had a representation of 13.3%, thanks to the push of the new Alianza Verde party, and the center-right remained at 7.9%.

|

The 2014 legislative elections meant the consolidation of a new right-wing party, the Democratic Center, created by Uribe after his separation from the U Party, which had been left in the hands of Santos, who that year would win reelection as Colombian president. The Democratic Center came in second place in the Senate elections, with only one senator less than the U Party (Sanchez, 2018). In 2014, the right went on to control 48.1% of the Senate, from agreement with the ideological realignment of the party system. Thus, several experts came to classify the Partido de la U as center-right, label which they also began to grant to the Partido Liberal, in a political space shared with Cambio Radical; these three parties formed the "Unidad Nacional" (Castillo, 2018). With this, the center-right totaled 19.6% of the seats, while the center-left obtained 9.8%, due to the votes achieved by the Green Party and the Progressives, the latter led by Gustavo Petro, current presidential candidate . The left only reached 4.9%, represented by the minorities of the Polo Democrático, the Unión Patriótica, Marcha Patriótica and the groups that came from the demobilized guerrillas.

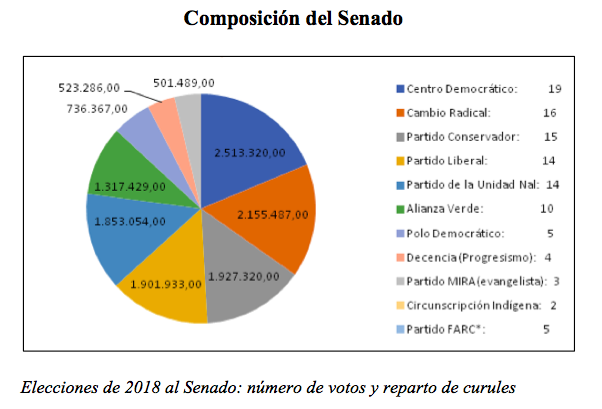

In the legislative elections of March 11, there was a reinforcement of right-wing positions, with the return of some parties which in previous elections had slid towards the center-right by defending the negotiation with the FARC and which now wanted to counteract the fear of part of the population of a rise of the radical left, in a very polarized electoral process. Thus, the right rose to 55.2% of the senators, led by those of the Democratic Center, while the center-right fell to 15.9%. The moderate and radical left increased their presence: the center-left rose to 11.5% and the left to 9%. This last percentage does not include the five seats guaranteed to the FARC, which despite not winning any senator electorally, will have those five seats guaranteed by the Peace Accords.

House of Representatives

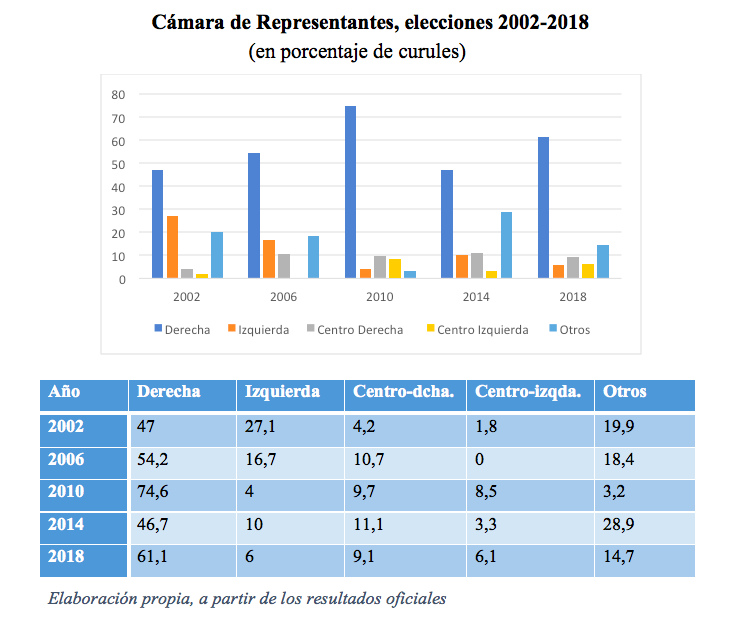

The results in the 2002-2018 period of the elections for the House of Representatives, held simultaneously with those for the Senate, do not differ much from what was discussed in the previous epigraph; however, they present some variations that should be considered.

The institution was quite affected by parapolitics scandals, a factor that influenced the political polarization of the country, which would be reflected in the elections throughout this period. In 2002, the right won 47% of the seats in the House, with the Liberal Party having the largest representation; the left won 27.1%. From then on, the center-right, which in 2002 obtained 4.2% of the representatives (the center-left took 1.8%) began to take a certain configuration, as the contours of the two traditional parties -Conservative and Liberal- blurred with the division into factions, from which new parties would emerge; this ended the bipartisanship experienced in Colombia throughout the 20th century: the Conservative governed for 48 years and the Liberal for 13.

|

The emergence of the Partido de la U, led by Álvaro Uribe and the wide acceptance of his political figure (Uribe became president in 2002 and was reelected in 2006), led for the first time a party other than the two traditional ones to come in second place in the 2006 legislative elections, in which the Partido de la U won 16.7% of the seats in the Chamber, raising the representation of the right to 54.2%. For its part, the left dropped its representation to 16.7% and entered a period of special political weakness (these elections were not good for the center-left either, which did not obtain representation). At a time of President Uribe's successes against the guerrillas, with measures supported by a large part of the population, although not without controversy, the left-wing parties were weighed down by sharing certain ideological assumptions with the guerrillas, as political scientist Andrés Dávila of the Universidad de los Andrés Dávila of the Universidad de los Andres points out.

This dynamic led to an even greater increase of the right wing and a new decline of the left wing in the House of Representatives in 2010, in parallel with what happened in the Senate, in a year in which the candidate promoted by Uribe, Juan Manuel Santos, would also win the presidency. The Partido de la U was ahead of the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party in the House of Representatives, with these three right-wing parties accounting for 74.6% of the seats, the highest percentage of the entire period studied; the center-right party reached 9.7%. For its part, the left, whose largest party was the Polo Democrático, reached only 4%, its worst share in the period, minimally compensated by the maximum representation of the center-right, although this was a modest 8.5%.

The 2014 elections brought with them the presence of a new party headed by Uribe, the Democratic Center, which positioned itself to the right of the previous ones by positioning itself forcefully against the continuation of the peace dialogues with the FARC propitiated by President Santos (El periodico, 2017). The rupture between Santos and Uribe caused their electorate to split, so that in the elections to the House of Representatives the Liberal Party won, followed by the U Party, the Conservative Party and the Democratic Center. Taking into account the shift towards more moderate positions of some of these formations, when grouping them together we have that the right-wing advocates dropped to 46.7% of the seats in the House, while the center-right rose to 11.1%. The left, with the Polo Democrático, improved its representation somewhat to 10%, and the center-left languished at 3.3%.

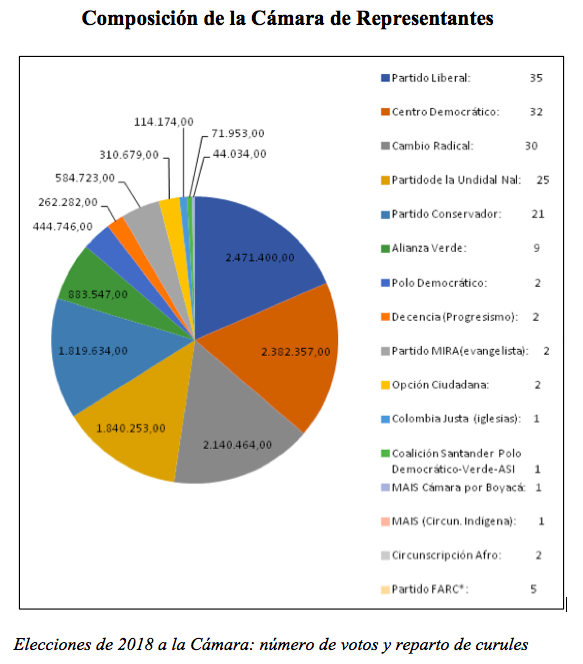

Four years later, last March 11, the Liberal Party won again the elections to the House of Representatives, followed by the Democratic Center, the Radical Change, the U Party and the Conservative Party. Some of these formations returned during the electoral campaign to clear right-wing positions that they had previously moderated, so that the right wing added 61.1% of the seats (Sánchez, 2018), compared to 6% for the left. For its part, the center-right scored 9.1% and the center-left 6.1%. To these figures must be added the five seats in the House granted by the agreement de Paz to the FARC, which also failed to win any by citizen vote, as in the Senate. With this enlargement, the Colombian bicameral congress goes from 268 to 280 members (the ten members of the FARC party and two that will correspond to the presidential ticket that comes second in the presidential elections).

|

The division of the left

The analysis carried out allows us to affirm that right-wing political approaches have remained in the majority in Colombia so far this century, as was the case in previous decades, although no longer in the hegemonic framework of two major parties, but of a wider range of partisan options. In a period in which in many other Latin American countries there were turns to the left -notably, the Bolivarian revolutions- Colombia was a clear exception. In this time, the right in Colombia (not including the center-right) has controlled between 43.3% (2002) and 66.7% (2010) of the Senate seats and between 46.7% (2014) and 74.6% (2010) of those in the House of Representatives. In contrast, the left (not including the equally reduced center-left) has remained a minority: it has moved between 4.9% (2014) and 19% (2006) of the Senate, and between 4% (2010) and 27.1% (2002) of the House.

The 2016 Peace agreement and the integration of the FARC into political life have so far not led to a significant electoral boom of the left. In the legislative elections of March 11, 2018, the right actually recovered positions compared to 2014 in the two institutions of the Contreso, while the left, although it certainly improved its presence in the Senate, but far from the levels of 2002 and 2006, instead lost space in the Chamber.

The fear of broad sectors of the population that the political benefits granted to the FARC, such as guaranteed access to media or campaign financing, would contribute to an electoral advance of the ex-guerrillas did not materialize in these elections. The results of the October 2016 plebiscite, which rejected the agreement de Paz (this came into force in 2017 after some changes, without a new plebiscite), were again reflected in the past legislative elections: Colombians oppose the participation of former members of the belligerent group in politics. FARC candidates obtained only 0.28% of the votes. In addition, this party announced days before the legislative elections that it will not run in the presidential elections, for which the maximum leader of group, Rodrigo Londoño, was running as candidate .

Is Colombia a conservative country? Why has the left in Colombia been so weak electorally? These recurring questions about Colombian politics are not easy to answer. "The left is a sector that has traditionally been very much divided among doctrinal tendencies, for strategic reasons and even by personalities", explains Yeann Basset, director of the Observatory of Electoral Processes of the Universidad del Rosario.

It is worth highlighting what Fabio López, author of the book "Izquierdas y cultura política", said in response to the question of whether there is a left in Colombia:

"One thing is that we come from a defeat, internationally thought, of the left, an enormous setback of the workers' movement, a discrediting of socialist ideas, and another thing is the disappearance of the causes, of the structural reasons that motivate at international and national level some leftist ideas, some roots and some justifications, to appeal to the rescue or better restructuring, a new beginning of some leftist approaches in Colombia".

One of the reasons usually given to explain the difficulty of the left in gaining greater support is the negative weight of the guerrilla subversion. In Colombia, after the constant conflicts, massacres and the pain that the armed conflict has left on Colombians, leftist parties have not achieved the support of the society as in neighboring countries since there is a direct association of leftist party with the guerrillas and what comes with them. The arrival of political leaders such as Uribe to the presidency intensified this association and increased the taboo present today in a large part of the citizens of supporting a leftist party. At the same time, the left has not done much to repair this bad image; the great internal fragmentation and differences among political leaders have not helped the training of a solid left with the capacity to increase its representation in the congress.

Opportunity for the presidential election?

The presidential elections on May 27 are an opportunity for the left to improve its electoral results, which in any case could advance in the future to the extent that peace is consolidated and the past of violence can be forgotten.

The political polarization, which on other occasions has harmed the left, this time is assuming a certain unity of this ideological sector around the candidacy of Gustavo Petro, former mayor of Bogota. The celebration on March 11 of primaries on the right, won by the pro-Uribe Iván Duque, and on the left, won by Petro (Sánchez, 2018), have accentuated the polarization for the presidential elections, increasing citizen mobilization (in the legislative elections there were five more points of participation) and attracting media attention to both candidates. Polarization, at the same time, has reduced support to possible centrist alternatives, as divided as the left was before, so that it cannot be ruled out that Petro may go to a second round, on June 17. A victory against the odds for Petro, for which he should attract the bulk of the moderate electorate, would not mean a radical change in legislative policies, as the congress revalidated last March 11 the dominance of the right.