Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs World order, diplomacy and governance .

ESSAY / Álvaro de Lecea Larrañaga

From the moment colonial empires left the African continent and the new republics celebrated their first democratic elections, the issue of election violence has been present in the majority of the countries. It is a problem that has not changed and that keeps disturbing national and international supporters of a peaceful democratization of the African continent. It is not the first time in history we know about election violence in democratic states, such as France during the nineteenth century; nevertheless, the African dynamics are quite peculiar.

Violence, in general terms, has become a political instrument in the African democratic dynamics (Laakso, 2007). Depending on the actor making use of it, the motivation behind it is different. It is also important to take into account the historical, political, partner-cultural and economic context of each country to understand the purposes of the usage of this controversial mechanism. The spur is not the same for the ruling party or the opposition party, or other groups like the youth. Hence the use of violence has a lot of influence in the outcomes of an election process as it is an effective means that shapes the democratic dynamics when it comes to the election of the representatives at all stages of the electoral processes. For example, the ruling parties use it to avoid being removed from their powerful positions and all the benefits that come from them (Mehler, 2007).

This issue of power, with a high level of influence of money, is probably the most common motivation for every actor involved in these dynamics (Muna & Otieno, 2020, pp. 92-111). Not only the ruling powers but the ones trying to substitute them or the ones trying to impose a new order are, in some way, motivated by the powerful positions they could attain. The violence therefore permeates all party structures and is also noticeable within the parties.

The issue of intra-party violence has not received a lot of attention due to more frequency of state inspired violence against the opposition. Yet it is becoming more prevalent especially in political parties that hold power. This is because the belief is usually entrenched that if one represents the ruling party the chances of getting elected get higher. It should also be noted that the risk of intra-party violence increases as inter-party competition decreases, making intra-party violence more common in districts where a single party dominates (Bech Seeberg, Skaaning, & Wahman, 2017).

The timing of the violence is very relevant to understand the problem of election violence. The different three kinds of election violence (pre-election violence, post-election violence and violence during the Election Day) carry different connotations with them (Daxecker, 2013). They are the result of the general context of the country and represent the behaviour of their citizens towards the democratic principles of the nation. This can also be a response to the electoral campaigns of both the ruling and opposition parties, which sometimes involve violent means too.

Pre-election violence is normally recorded within parties as they carry out their primaries to select representatives and during the campaign process in a bid to hinder opponents from getting access to the people. Violence on Election Day is usually designed to disrupt areas where some candidates suspect they will lose or feel the election process has not been fair. While post-election violence is mainly an expression of dissatisfaction with the outcome of the election.

The role of average and international observers are also key for drafting the big picture of the problems involving election violence. These to some extent can escalate the conflict or reduce it. The power of information is huge and these agents are the most reliable sources to the local and international communities. If an international observer, such as a Committee from the United Nations, declares an election fraud, post-election violence is a very possible outcome (Daxecker, 2012). However, the average, and more concretely a trustworthy local average agent, has the power to calm the masses and bring peace.

Finally, the electoral system chosen by each country will also have a direct effect on the violence because of the interests behind the election. The plurality voting is the most used system among African states. These kinds of systems are also known as winner-takes-all, because the winner gets all the power. Even if it is not necessarily a negative system, as successful countries such as France or Brazil also use them, the difference of power between a common citizen and a politician is so big in Africa that the interest of getting those posts is higher (Reynolds, 2009). This will cause that any means justified to get there, including the use of violence.

To further analyse the motivations behind election violence in Africa and the effects it has on the region, and to try to offer a functional solution for this issue the article explores two case studies: Kenya 2007 and Burundi 2010.

African election violence case studies

Kenya 2007

The presidential and parliamentary elections held in Kenya in 2007 are a great example of election violence where external factors had influences on the outcomes. However, these external factors were not the only ones causing the violence. Internal issues such as the historical culture of the country, the electoral system or the will of power were also influential in this case. To understand the big picture, it is always important to analyze every relevant aspect.

Since the first multi-party democratic elections in Kenya, held in 1992, post-election violence has been very present. During the almost thirty years of dictatorship in Kenya after their independence from the British Crown, repression was promoted throughout the whole territory. Abuses of human rights, nepotism, widespread corruption and patronage were very common (Onyebadi & Oyedeji, 2011), therefore Kenyans are used to protest, violently if needed, against political fraud and suppression of their democratic rights.

Mwai Kibaki's victory in the 2007 elections brought a whole wave of violent protests because of the fraudulent accusations the elections received (Odhiambo Owuor, 2013). Not only the opposition leader Raila Odinga denounced the election as massively rigged, but also the international community did so. As they condemned the election as fraudulent, the United Nations intervened and helped reach a deal between both party leaders. In this case, the violence produced arrived after the elections (post-election violence) and was motivated by the fraudulent accusations made by international and national observers.

The solution reached was to recognise Kibaki as president and to create a new position of Executive Prime Minister for Odinga. Furthermore, they stipulated that cabinet positions were to be shared by the disputants and their political parties. This characteristic outcome was accepted with more enthusiasm by the Kenyan people because it divided the power in more than one person and, therefore, the abuse of it as it had happened before was not so probable. The electoral system, which is explained later on, has helped these abuses to be produced, so this different outcome meant a significant change in the Kenyan policy-making.

In the case of Kenya, average is very relevant, as the two most successful newspapers, the "Daily Nation" and "The Standard", with a combined strength of 75% market share, do not receive funding from the government. Without falling into sensationalism, these newspapers were able to become agents of peace and reconciliation. As violence raged in the post-election period, the newspapers adopted a thematic approach to reaching a peaceful outcome (Onyebadi & Oyedeji, 2011).

This conflict, apart from the effects it had on the electoral outcome, influenced the economic situation of the country. The annual percentage growth of GDP fell from 6.8% in 2007 to 0.2% in 2008, the annual percentage of GDP per capita growth was negative (-2.5%) and the growth on the percentage of employment regarding total labour force began increasing again in 2008, going from 2.5% that year to 2.7% in 2009 (World Bank, 2020). However, this data is biased because of the economic recession several countries, including Kenya, suffered due to the 2008 financial crisis.

Finally, Kenya's first-past-the-post single member constituency electoral system gives the electoral winner plenty of power. Moreover, the economic inequality, the domination of the powerful elites of the country who are very influential in the political system and the fact that Kenyan political parties are not usually founded on ideology but serve the ideas of the founders, produce a form of democracy that represents the few rather than the majority. Therefore, it is very complicated to terminate the desire for political power from the Kenyan mindset.

Burundi 2010

Burundi's history has been marked by the Hutu-Tutsi rivalry. Since it got independence in 1962, the ethnic cleavages between the majority Hutu and minority Tutsi have been remarkable. The 2010 elections are not quite different from the rest, as the outcomes resulted in boycotts and violence. Burundi is a country that has used violence as a tool of solving conflicts several times and has a violent historical precedent regarding "democratic" elections (Mehler, 2007). Several prime ministers and presidents from the different ethnic groups have been assassinated throughout Burundi's democratic history, which has led to a series of coups and ethnic clashes.

During the 2010 elections, the United Nations also sent a mission to observe the democratic process followed. They affirmed that the winning party, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD), were able to campaign throughout the country, whereas the opposition parties had much less visibility (Palmans, n.d.).

The Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI), which is supposed to organise, conduct and supervise the elections independently from any party were not as transparent as they were meant to and didn't respect the rights of the political parties, which caused the boycott led by the opposition (Niang, n.d.). In Burundi too, elections have mainly been a struggle for power as a means of gaining access to economic resources through control of the state. So, the tensions have always been great during elections. Thus, violence tends to be used by nearly every actor involved.

The peculiarity within this case is that the violence didn't only take place after knowing the results of the elections, but also before the Election Day. Pre-election violence came as a consequence of systematic disagreement between CNDD-FDD and opposition parties. Although several institutions were created to ensure the legality and transparency of the election, such as the CENI, the CNDD-FDD tried to arrange the legal and institutional context to force the process into its advantage and ensure its victory against the opposition.

The pre-election violence transformed into post-election violence leading to the main opposition leader, Agathon Rwasa, having to flee the country. Even though the violence was not as widespread as in Kenya, the situation remained tense in the country. The results didn't change, and the political rivalries were further entrenched. In this case, the use of violence and coupled with display of power won the elections which created more fear and despair within the population.

Conclusion

Election violence is very common in several countries over the world, with an emphasis on Africa. There, it has become some kind of political instrument which, despite being anti-democratic by nature, is part of the policymaking, campaigning and electoral process. It is different depending on the timing it appears and plenty of factors influence its appearance and control. Within the most remarkable we can find the role of international and national observers, the role of the average, both national and international, and the will of power, usually linked to the economic benefits the winner receives. Furthermore, depending on who the actor is making use of it, the factors behind it can change drastically.

After having analysed the two case studies, Kenya 2008 and Burundi 2010, and having interpreted the impact these issues have had in their internal partner-economic parameters, it is also obvious that these anti-democratic practices do have some impact in every aspect of the society involved in it. Its most remarkable influence can be seen on the election outcome. In both cases, violence was key for establishing the results. In the case of Kenya, it was the motor that boosted a change in the policymaking, and in the case of Burundi, it helped the winning party keep the power.

The three main factors that influence this kind of policymaking and that should be reviewed and, if necessary, modified to end the violence are the electoral system most African countries follow, the ethnic nature of violence and the common African mindset regarding power. The majority of the electoral systems followed in Africa are winner-takes-all systems that makes it hard for the loser to give up power and lose the benefits it brings. Also, as the case of Burundi has shown, ethnic rivalries are a very common reason motivating the violent outcomes of elections, even if the state follows a democratic regime. This, together with the great will of power present on the African societies, demonstrated by the intra- and inter-party violence, provokes the unsustainable situation present nowadays.

REFERENCES

Bank, W. (2020). World Bank Database. Retrieved from https://data.bancomundial.org/

Bech Seeberg, M., Skaaning, S.-E., & Wahman, M. (2017). Candidate nomination, Intra-party Democracy, and Election Violence in Africa. ResearchGate.

Daxecker, U. E. (2012). The cost of exposing cheating: International election monitoring, fraud, and post-election violence in Africa. Journal of Peace Research.

Daxecker, U. E. (2013). All quiet on Election Day? International election observation and incentives for pre-election violence in African elections. Electoral Studies, 1-12.

Laakso, L. (2007). Insights into Electoral Violence in Africa. In M. Basedau, G. Erdmann, & A. Mehler, Votes, Money and Violence: Political Parties and Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 224-252). South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Mehler, A. (2007). Political Parties and Violence in Africa: Systematic Reflections against Empirical Background. In M. Basedau, G. Erdmann, & A. Mehler, Votes, Money and Violence: Political Parties and Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 194-223). South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Muna, W., & Otieno, M. (2020). The 'Money Talks Factor' in Kenya's Public Policy and Electoral Democracy.

Niang, M. A. (n.d.). Case study: Burundi. EISA.

Odhiambo Owuor, F. (2013). The 2007 General Elections in Kenya: Electoral Laws and Process. EISA, 113-123.

Onyebadi, U., & Oyedeji, T. (2011). Newspaper coverage of post-political election violence in Africa: an assessment of the Kenyan example. average War & Conflict, 215-230.

Palmans, E. (n.d.). Burundi's 2010 Elections: Democracy and Peace at Risk? European Centre for Electoral Support.

Reynolds, A. (2009). Elections, Electoral Systems, and Conflict in Africa. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 75-83.

The wave of diplomatic recognition of Israel by some Arab countries constitutes a shift in regional alliances

![Dubai, the largest city in the United Arab Emirates [Pixabay]. Dubai, the largest city in the United Arab Emirates [Pixabay].](/documents/16800098/0/acuerdos-abraham-blog.jpg/43eef7ab-96b1-fcd7-b19d-4d682361590c?t=1621884303752&imagePreview=1)

▲ Dubai, the largest city in the United Arab Emirates [Pixabay].

ANALYSIS / Ann M. Callahan

With the signing of the Abraham Accords, seven decades of enmity between the states were concluded. With a pronounced shift in regional alliances and a convergence of interests crossing traditional alignments, the agreements can be seen as a product of these regional changes, commencing a new era of Arab-Israeli relations and cooperation. While the historic peace accords seem to present a net positive for the region, it would be a mistake to not take into consideration the losing party in the deal; the Palestinians. It would also be a mistake to dismiss the passion with which many people still view the Palestinian issue and the apparent disconnect between the Arab ruling class and populace.

On the 15th of September, 2020, a joint peace deal was signed between the State of Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and the United States, known also as the Abraham Accords Peace Agreement. The Accords concern a treaty of peace, and a full normalization of the diplomatic relations between the United Emirates and the State of Israel. The United Arab Emirates stands as the first Persian Gulf state to normalize relations with Israel, and the third Arab state, after Egypt in 1979 and Jordan in 1994. The deal was signed in Washington on September 15 by the UAE's Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan and the Prime Minister of the State of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu. It was accepted by the Israeli cabinet on the 12th of October and was ratified by the Knesset (Israel's unicameral parliament) on the 15th of October. The parliament and cabinet of the United Arab Emirates ratified the agreement on the 19th of October. On the same day, Bahrain confirmed its pact with Israel through the Accords, officially called the Abraham Accords: Declaration of Peace, Cooperation, and Constructive Diplomatic and Friendly Relations. Signed by Bahrain's Foreign Minister Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the President of the United States Donald Trump as a witness, the ratification indicates an agreement between the signatories to commence an era of alliance and cooperation towards a more stable, prosperous and secure region. The proclamation acknowledges each state's sovereignty and agrees towards a reciprocal opening of embassies and as well as stating intent to seek out consensus regarding further relations including investment, security, tourism and direct flights, technology, healthcare and environmental concerns.

The United States played a significant role in the accords, brokering the newly signed agreements. President of the United States, Donald Trump, pushed for the agreements, encouraging the relations and negotiations and promoting the accords, and hosting the signing at the White House.

As none of the countries involved in the Abraham Accords had ever fought against each other, these new peace deals are not of the same weight or nature as Egypt's peace deal with Israel in 1979. Nevertheless, the accords are much more than a formalizing of what already existed. Now, whether or not the governments collaborated in secret concerning security and intelligence previously, they will now cooperate publicly through the aforementioned areas. For Israel, Bahrain and the UAE, the agreements pave a path for the increase of trade, investment, tourism and technological collaboration. In addition to these gains, a strategic alliance against Iran is a key motivator as the two states and the U.S. regard Iran as the chief threat to the region's stability.

Rationale

What was the rationale for this diplomatic breakthrough and what prompted it to take place this year? It could be considered to be a product of the confluence of several pivotal impetuses.

The accords are seen as a product of a long-term trajectory and a regional reality where over the course of the last decade Arab states, particularly around the Gulf, have begun to shift their priorities. The UAE, Bahrain and Israel had found themselves on the same side of more than one major fissure in the Middle East. These states have also sided with Israel regarding Iran. Saudi Arabia, too, sees Shiite Iran as a major threat, and while, as of now, it has not formalized relations with Israel, it does have ties with the Hebrew state. This opposition to Tehran is shifting alliances in the region and bringing about a strategic realignment of Middle Eastern powers.

Furthermore, opposition to the Sunni Islamic extremist groups presents a major threat to all parties involved. The newly aligned states all object to Turkey's destabilising support of the Muslim Brotherhood and its proxies in the regional conflicts in Gaza, Libya and Syria. Indeed, the signatories' combined fear of transnational jihadi movements, such as Al-Qaeda and ISIS derivatives, has aligned their interests closer to each other.

In addition, there has been a growing frustration and fatigue with the Palestinian Cause, one which could seem endless. A certain amount of patience has been lost and Arab nations that had previously held to the Palestinian cause have begun to follow their own national interests. Looking back to late 2017, when the Trump administration officially recognised Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, had it been a decade earlier there would have been widespread protests and resulting backlash from the regional leaders in response, however it was not the case. Indeed, there was minimal criticism. This may indicate that, at least for the regional leaders, that adherence to the Palestinian cause is lessening in general.

The prospects of closer relations with the economically vibrant state of Israel, and by extension with that of the United States is increasingly attractive to many Arab states. Indeed, expectations of an arms sale of U.S. weapon systems to the UAE, while not written specifically into the accords, is expected to come to pass through a side agreement currently under review by Congress.

From the perspective of Israel, the country has gone through a long political crisis with, in just one year alone, three national elections. In the context of these domestic efforts, prime minister Netanyahu raised propositions of annexing more sections of the contended West Bank. Consequently, the UAE campaigned against it and Washington called for Israel to choose between prospects of annexation or normalization. The normalization was concluded in return for suspending the annexation plans. There is discussion regarding whether or not the suspending of the plans are something temporary or a permanent cessation of the annexation. There is a discrepancy between the English and Arabic versions of the joint treaty. The English version declared that the accord "led to the suspension of Israel's plans to extend its sovereignty". This differs slightly, however significantly, from the Arabic copy in which "[the agreement] has led to Israel's plans to annex Palestinian lands being stopped." This inconsistency did not go unnoticed to the party most affected; the Palestinians. There is a significant disparity between a temporary suspension as opposed to a complete stopping of annexation plans.

For Netanyahu, being a leading figure in a historic peace deal bringing Israel even more out of its isolation without significant concessions would certainly boost his political standing in Israel. After all, since Israel's creation, what it has been longing for is recognition, particularly from its Arab neighbours.

Somewhat similarly to Netanyahu, the Trump Administration had only to gain through the concluding of the Accords. The significant accomplishment of a historic peace deal in the Middle East was certainly a benefit especially leading up to the presidential elections, which took place earlier this November. On analyzing the Administration's approach towards the Middle East, its strategy clearly encouraged the regional realignment and the cultivation of the Gulf states' and Israel's common interests, culminating in the joint accords.

Implications

As a whole, the Abraham Accords seem to have broken the traditional alignment of Arab States in the Middle East. The fact that normalization with Israel has been achieved without a solution to the Palestinian issue is indicative of the shift in trends among Arab nations which were previously staunchly adherent to the Palestinian cause. Already, even Sudan, a state with a violent past with Israel, has officially expressed its consent to work towards such an agreement. Potentially, other Arab states are thought to possibly follow suit in future normalization with Israel.

Unlike Bahrain and the UAE, Sudan has sent troops to fight against Israel in the Arab-Israeli wars. However, following the UAE and Bahrain accords, a Sudan-Israel normalization agreement transpired on October 23rd, 2020. While it is not clear if the agreement solidifies full diplomatic relations, it promotes the normalization of relations between the two countries. Following the announcement of their agreement, the designated foreign minister, Omar Qamar al-Din, clarified that the agreement with Israel was not actually a normalization, rather an agreement to work towards normalization in the future. It is only a preliminary agreement as it requires the approval of an elected parliament before going into force. Regardless, the agreement is a significant step for Sudan as it had previously considered Israel an enemy of the state.

While clandestine relations between Israel and the Gulf states were existent for years, the founding of open relations is a monumental shift. For Israel, putting aside its annexation plans was insignificant in comparison with the many advantages of the Abraham Accords. Contrary to what many expected, no vast concessions were to be made in return for the recognition of sovereignty and establishment of diplomatic ties for which Israel yearns for. In addition, Israel is projected to benefit economically from its new forged relations with the Gulf states between the increased tourism, direct flights, technology and information exchange, commercial relations and investment. Already, following the Accord's commitment, the US, Israel and the UAE have already established the Abraham Fund. Through the program more than $3 billion dollars will be mobilized in the private sector-led development strategies and investment ventures to promote economic cooperation and profitability in the Middle East region through the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, Israel and the UAE.

The benefits of the accords extend to a variety of areas in the Arab world including, most significantly, possible access to U.S. defence systems. The prospect of the UAE receiving America's prestigious F-35 systems is in fact underway. President Trump, at least, is willing to make the sale. However, it has to pass through Congress which has been consistently dedicated to maintaining Israel's qualitative military edge in the region. According to the Senate leader Mitch McConnell (Rep, KY), "We in congress have an obligation to review any U.S. arm sale package linked to the deal [...] As we help our Arab partners defend against growing threats, we must continue ensuring that Israel's qualitative military edge remains unchallenged". Should the sale be concluded, it will stand as the second largest sale of U.S. arms to one particular nation, and the first transfer of lethal unmanned aerial systems to any Arab ally. The UAE would be the first Arab country to possess the Lockheed Martin 5th generation stealth jet, the most advanced on the market currently.

There is discussion within Israel regarding possible UAE acquisition of the F-35 systems. Prime Minister Netanyahu did the whole deal without including the defense minister and the foreign minister, both political rivals of Netanyahu in the Israeli system. As can be expected, the Israeli defense minister does have a problem regarding the F-35 systems. However, in general, the Accords are extremely popular in Israel.

Due to Bahrain's relative dependence on Saudi Arabia and the kingdom's close ties, it is very likely that it sought out Saudi Arabia's approval before confirming its participation in the Accords. The fact that Saudi Arabia gave permission to Bahrain could be seen as indicative, to a certain extent, of their stance on Arab-Israeli relations. However, the Saudi state has many internal pressures preventing it, at least for the time being, from establishing relations.

For over 250 years, the ruling Saudi family has had a particular relationship with the clerical establishment of the Kingdom. Many, if not the majority of the clerics would be critical of what they would consider an abandonment of Palestine. Although Mohammed bin Salman seems more open to ties with Israel, his influential father, Salman bin Abdulaziz sides with the clerics surrounding the matter.

Differing from the United Arab Emirates, for example, Saudi Arabia gathers a B amount of its legitimacy through its protection of Muslims and promotion of Islam across the world. Since before the establishment of the state of Israel, the Palestinian cause has played a crucial role in Saudi Arabia's regional activities. While it has not prevented Saudi Arabia from engaging in undisclosed relations with Israel, its stance towards Palestine inhibits a broader engagement without a peace deal for Palestine. This issue connected to a critical strain across the region: that between the rulers and the ruled. One manifestation of this discrepancy between classes is that there seems to be a perception among the people of the region that Israel, as opposed to Iran, is the greater threat to regional security. Saudi Arabia has a much larger population than the UAE or Bahrain and with the extensive popular support of the Palestinian cause, the establishment of relations with Israel could elicit considerable unrest.

While Saudi Arabia has engaged in clandestine ties with Israel and been increasingly obliging towards the state (for instance, opening its air space for Israeli direct flights to the UAE and beyond), it seems unlikely that Saudi Arabia will establish open ties with Israel, at least for the near future.

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has only heightened prevailing social, political and economic tensions all throughout the Middle East. Taking this into account, in fear of provoking unrest, it can be expected that many rulers will be hesitant, or at least cautious, about initiating ties with the state of Israel.

That being said, in today's hard-pressed Middle East, Arab states, while still backing the Palestinian cause, are more and more disposed to work towards various relations with Israel. Saudi Arabia is arguably the most economically and politically influential Arab state in the region. Therefore, if Saudi Arabia were to open relations with Israel, it could invoke the establishment of ties with Israel for other Arab states, possibly invalidating the longstanding idea that such relations could come about solely though the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Regarding Iran, it cannot but understand the significance and gravity of the Accords and recent regional developments. Just several nautical miles across the Gulf to Iran, Israel has new allies. The economic and strategic advantage that the Accords promote between the countries is undeniable. If Iran felt isolated before, this new development will only emphasize it even more.

In the words of Mike Pompeo, the current U.S. Secretary of State, alongside Bahrain's foreign minister, Abdullatif Al-Zayani, and Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, the accords "tell malign actors like the Islamic Republic of Iran that their influence in the region is waning and that they are ever more isolated and shall forever be until they change their direction".

Apart from Iran, in the Middle East Turkey and Qatar have been openly board member in their opposition to Israel and the recent Accords. Qatar maintains relations with two of Israel's most critical threats, both Iran and Hamas, the Palestinian militant group. Qatar is a staunch advocate of a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict. One of Qatar's most steady allies in the region is Turkey. Israel, as well as the UAE, have significant issues with Ankara. Turkey's expansion and building of military instructions in Libya, Sudan and Somalia demonstrate the regional threat that it poses for Israel and the UAE. For Israel in particular, besides Turkey's open support of Hamas, there have been clashes concerning Ankara's interference with Mediterranean maritime economic sovereignty.

With increasing intensity, the President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has made clear Turkey's revisionist actions. They harshly criticized UAE's normalization with Israel and even said that they would consider revising Ankara's relations with Abu Dhabi. This, however, is somewhat incongruous as Turkey has maintained formal diplomatic relations with Israel since right after its birth in 1949. Turkey's support of the Muslim Brotherhood throughout the region, including in Qatar, is also a source of contention between Erdogan and the UAE and Israel, as well as Saudi Arabia. Turkey is Qatar's largest beneficiary politically, as well as militarily.

In the context of the Abraham Accords, the Palestinians would be the losers undoubtedly. While they had a weak negotiating hand to begin with, with the decreasing Arab solidarity they depend on, they now stand even weaker. The increasing number of Arab countries normalizing relations with Israel has been vehemently condemned by the Palestinians, seeing it as a betrayal of their cause. They feel thoroughly abandoned. It leaves the Palestinians with very limited options making them severely more debilitated. It is uncertain, however, whether this weaker position will steer Palestinians towards peacemaking with Israel or the contrary.

While the regional governments seem more willing to negotiate with Israel, it would be a severe mistake to disregard the fervour with which countless people still view the Palestinian conflict. For many in the Middle East, it is not so much a political stance as a moral obligation. We shall see how this plays out concerning the disparity between the ruling class and the populace of Arab or Muslim majority nations. Iran will likely continue to advance its reputation throughout the region as the only state to openly challenge and oppose Israel. It should amass some amount of popular support, increasing yet even more the rift between the populace and the ruling class in the Middle East.

Future prospects

The agreement recently reached between President Trump's Administration and the kingdom of Morocco by which the U.S. governments recognizes Moroccan sovereignty over the disputed territory of Western Sahara in exchange for the establishment of official diplomatic relations between the kingdom and the state of Israel is but another step in the process Trump would have no doubt continued had he been elected for a second term. Despite this unexpected move, and although the Trump Administration has indicated that other countries are considering establishing relations with Israel soon, further developments seem unlikely before the new U.S. Administration is projected to take office this January of 2021. President-elect Joe Biden will take office on the 20th of January and is expected to instigate his policy and approach towards Iran. This could set the tone for future normalization agreements throughout the region, depending on how Iran is approached by the incoming administration.

In the United States, the signatories of the Abraham Accords have, in a time of intensely polarized politics, enhanced their relations with both Republicans as well as Democrats though the deal. In the future we can expect some countries to join the UAE, Bahrain and Sudan in normalization efforts. However, many will stay back. Saudi Arabia remains central in the region regarding future normalization with Israel. As is the case across the region, while the Arab leaders are increasingly open to ties with Israel, there are internal concerns, between the clerical establishment and the Palestinian cause among the populace - not to mention rising tensions due to the ongoing pandemic.

However, in all, the Accords break the strongly rooted idea that it would take extensive efforts in order for Arab states to associate with Israel, let alone establish full public normalization. It also refutes the traditional Arab-state consensus that there can be no peace with Israel until the Palestinian issue is en route to resolution, if not fully resolved.

Behind the tension between Qatar and its neighbours is the Qatari ambitious foreign policy and its refusal to obey

Recent diplomatic contacts between Qatar and Saudi Arabia have suggested the possibility of a breakthrough in the bitter dispute held by Qatar and its Arab neighbors in the Gulf since 2017. An agreement could be within reach in order to suspend the blockade imposed on Qatar by Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain (and Egypt), and clarify the relations the Qataris have with Iran. The resolution would help Qatar hosting the 2022 FIFA World Cup free of tensions. This article gives a brief context to understand why things are the way they are.

Ahmad Bin Ali Stadium, one of the premises for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar

ARTICLE / Isabelle León

The diplomatic crisis in Qatar is mainly a political conflict that has shown how far a country can go to retain leadership in the regional balance of power, as well as how a country can find alternatives to grow regardless of the blockade of neighbors and former trading partners. In 2017, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain broke diplomatic ties with Qatar and imposed a blockade on land, sea, and air.

When we refer to the Gulf, we are talking about six Arab states: Saudi Arabia, Oman, UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait. As neighbors, these countries founded the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in 1981 to strengthen their relation economically and politically since all have many similarities in terms of geographical features and resources like oil and gas, culture, and religion. In this alliance, Saudi Arabia always saw itself as the leader since it is the largest and most oil-rich Gulf country, and possesses Mecca and Medina, Islam's holy sites. In this sense, dominance became almost unchallenged until 1995, when Qatar started pursuing a more independent foreign policy.

Tensions grew among neighbors as Iran and Qatar gradually started deepening their trading relations. Moreover, Qatar started supporting Islamist political groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood, considered by the UAE and Saudi Arabia as terrorist organizations. Indeed, Qatar acknowledges the support and assistance provided to these groups but denies helping terrorist cells linked to Al-Qaeda or other terrorist organizations such as the Islamic State or Hamas. Additionally, with the launch of the tv network Al Jazeera, Qatar gave these groups a means to broadcast their voices. Gradually the environment became tense as Saudi Arabia, leader of Sunni Islam, saw the Shia political groups as a threat to its leadership in the region.

Consequently, the Gulf countries, except for Oman and Kuwait, decided to implement a blockade on Qatar. As political conditioning, the countries imposed specific demands that Qatar had to meet to re-establish diplomatic relations. Among them there were the detachment of the diplomatic ties with Iran, the end of support for Islamist political groups, and the cessation of Al Jazeera's operations. Qatar refused to give in and affirmed that the demands were, in some way or another, a violation of the country's sovereignty.

A country that proves resilient

The resounding blockade merited the suspension of economic activities between Qatar and these countries. Most shocking was, however, the expulsion of the Qatari citizens who resided in the other GCC states. A year later, Qatar filed a complaint with the International Court of Justice on grounds of discrimination. The court ordered that the families that had been separated due to the expulsion of their relatives should be reunited; similarly, Qatari students who were studying in these countries should be permitted to continue their studies without any inconvenience. The UAE issued an injunction accusing Qatar of halting the website where citizens could apply for UAE visas as Qatar responded that it was a matter of national security. Between accusations and statements, tensions continued to rise and no real improvement was achieved.

At the beginning of the restrictions, Qatar was economically affected because 40% of the food supply came to the country through Saudi Arabia. The reduction in the oil prices was another factor that participated on the economic disadvantage that situation posed. Indeed, the market value of Qatar decreased by 10% in the first four weeks of the crisis. However, the country began to implement measures and shored up its banks, intensified trade with Turkey and Iran, and increased its domestic production. Furthermore, the costs of the materials necessary to build the new stadiums and infrastructure for the 2022 FIFA World Cup increased; however, Qatar started shipping materials through Oman to avoid restrictions of UAE and successfully coped with the status quo.

This notwithstanding, in 2019, the situation caused almost the rupture of the GCC, an alliance that ultimately has helped the Gulf countries strengthen economic ties with European Countries and China. The gradual collapse of this organisation has caused even more division between the blocking countries and Qatar, a country that hosts the largest military US base in the Middle East, as well as one of Turkey, which gives it an upper hand in the region and many potential strategic alliances.

The new normal or the beginning of the end?

Currently, the situation is slowly opening-up. Although not much progress has been made through traditional or legal diplomatic means to resolve this conflict, sports diplomacy has played a role. The countries have not yet begun to commercialize or have allowed the mobility of citizens, however, the event of November 2019 is an indicator that perhaps it is time to relax the measures. In that month, Qatar was the host of the 24th Arabian Gulf Cup tournament in which the Gulf countries participated with their national soccer teams. Due to the blockade, UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain had boycotted the championship; however, after having received another invitation from the Arabian Gulf Cup Federation, the countries decided to participate and after three years of tensions, sent their teams to compete. The sporting event was emblematic and demonstrated how sport may overcome differences.

Moreover, recently Saudi Arabia has given declarations that the country is willing to engage in the process to lift-up the restrictions. This attitude toward the conflict means, in a way, improvement despite Riyadh still claims the need to address the security concerns that Qatar generates and calls for a commitment to the solution. As negotiations continue, there is a lot of skepticism between the parties that keep hindering the path toward the resolution.

Donald Trump's administration recently reiterated its cooperation and involvement in the process to end Qatar's diplomatic crisis. Indeed, US National Security Adviser Robert O'Brien stated that the US hopes in the next two months there would be an air bridge that will allow the commercial mobilization of citizens. The current scenario might be optimistic, but still, everything has remained in statements as no real actions have been taken. This participation is within the US strategic interest because the end of this rift can signify a victorious situation to the US aggressive foreign policy toward Iran and its desire to isolate the country. This situation remains a priority in Trump's last days in office. Notwithstanding, as the transition for the administration of Joe Biden begins, it is believed that he would take a more critical approach on Saudi Arabia and the UAE, pressuring them to put an end to the restrictions.

This conflict has turned into a political crisis of retention of power or influence over the region. It is all about Saudi Arabia's dominance being threatened by a tiny yet very powerful state, Qatar. Although more approaches to lift-up the rift will likely begin to take place and restrictions will gradually relax, this dynamic has been perceived by the international community and the Gulf countries themselves as the new normal. However, if the crisis is ultimately resolved, mistrust and rivalry will remain and will generate complications in a region that is already prone to insurgencies and instability. All the countries involved indeed have more to lose than to gain, but three years have been enough to show that there are ways to turn situations like these around.

Soft power in the regional race for gaining the upper hand in the cultural and heritage influence among Muslims

A picture taken from the Kingdoms of Fire official trailer

ANALYSIS / Marina García Reina and Pablo Gurbindo

Kingdoms of Fire (in Arabic Mamalik al nar) is the new Emirati and Saudi funded super-production launched in autumn 2019 and born to face the Turkish control in the TV series and shows field for years. The production has counted on a budget of US$ 14 million. The series goes through the story of the last Sultan of Mamluk Egypt, Al-Ashraf Tuman Bay, in his fight against the Ottoman Sultan Selim. The production is the reflection of the regional rivalries in the race for gaining the upper hand in the cultural and heritage influence among Muslims.

Historicity

To understand the controversy this series has arisen we have to comprehend the context where the story takes place and the main characters of the story. The series talks about the Ottoman conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate of 1517. The Ottomans are already known for the general public, but who were the Mamelukes?

A Mameluke is not an ethnic group, it is a military class. The term comes from the Arab mamluk (owned) and it defines a class of slave soldiers. These mamluks had more rights than a common slave as they could carry weapons and hold positions of military responsibility. They were created in the ninth century by the Abbasid Caliphs with the purchase of young slaves and their training on martial and military skills. They became the base of military power in the Middle East. This military elite, similar to the Roman Praetorian Guard, was very powerful and could reach high positions in the military and in the administration. Different groups of Mamluks rebelled against their Caliphs masters, and in Egypt they successfully claimed the Caliphate in 1250, starting the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt and Syria. Their military prowess was demonstrated in 1260 in the battle of Ain Yalut where they famously defeated the Great Mongol Empire and stopped its expansion towards the west.

The Ottoman Empire was formed as one of the independent Turkish principalities that appeared in Anatolia after the fall of the Sultanate of Rum in the thirteenth century. It rapidly expanded across Anatolia and also reached the Balkans confronting the Byzantine Empire, direct heir of the Roman Empire. In 1453, after a long siege, they conquered Constantinople, sealing the fate of the Byzantine Empire.

By the sixteenth century, the Ottomans and the Mamluks were the two main powers of the Middle East, and as a perfect example of the "Thucydides trap", the conflict between these two regional powers became inevitable. In 1515, Ottoman Sultan Selim I launched a campaign to subdue the Mamluks. Incidentally, this is the campaign represented in the Arab series. In October 1516, in the battle of Marj Dabiq, the Mamluk Sultan Al-Ghawri was killed, and Syria fell into Ottoman rule. Tuman Bay II was proclaimed as Sultan and prepared the defence of Egypt. In 1517 the Ottomans entered Egypt and defeated Tuman Bay at the battle of Riadanieh, entering Cairo unopposed. Tuman Bay fled and, supported by the Bedouins, started a guerrilla campaign. But he was betrayed by a Bedouin chief and captured. On April 15, 1517, he was hanged to death on the city gates of Cairo and with him the Mamluk Sultanate ended.

With the end of the Mamluk rule, Egypt became an Ottoman province. The Ottoman control lasted from 1517 until the start of WWI, when the British Empire established a protectorate in the country after the Ottoman Empire entered the war.

A response to Turkish influence

Unlike Saudi Arabia, which until 2012, with the release of Wadjda, had never featured a film shot entirely in the country, other Middle Eastern countries such as Turkey and Iran have taken their first steps in the entertainment industry long before.

Turkey is a clear example of a country with a well-constituted cinema and art industry, hosting several film festivals throughout the year and having an established cinema industry called Yesilcamwhich can be understood as the Turkish version of the US Hollywood or the Indian Bollywood. The first Turkish narrative film was released in 1917. However, it was not till the 1950s when the Turkish entertainment industry truly started to emerge. Yesilcam was born to create a cinema appropriate for the Turkish audience in a period of national identity building and in an attempt to unify multiplicities. Thus, it did not only involve the creation of original Turkish films, but also the adaptation and Turkification of Western cinema.

One of the reasons that promoted the arising of the Turkish cinema was a need to respond to the Egyptian film industry, which was taking the way in the Middle East during the Second World War. It represents a Turkish nationalist feeling through a cinema that would embrace Turkey's Ottoman heritage and modern lifestyle.

Now, Turkish productions are known and watched by audiences worldwide, in more than 140 countries, which has turned Turkey into the world's second largest television shows distributor, generating US$ 350 million a year, only surpassed by the USA.

These Turkish productions embracing the Ottoman period are also a reflection of the current Neo-Ottoman policies carried out by the President Tayyip Erdogan, who many believe is trying to portray himself as a "modern Ottoman ruler and caliph for Muslims worldwide". It is clear that the Turkish President is aware of the impact of its TV shows, as he stated, in a 2016 speech referring to a Turkish show named "The Last Emperor"-narrating important events during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid-, that the West is treating Turkey in the same way as 130 years ago and, regarding Arabs, he stated that "until the lions start writing their own stories, their hunters will always be the heroes."

A soft power tool

Communication-especially visual communication and, therefore, cinema-plays an important role in either reinforcing the identity status quo or challenging self-views and other-views of the dynamic, multi-faceted self[1]. It is precisely the own and particular Saudi identity that wants to be portrayed by this series.

The massive sums invested in the production of Mamalik al nar, as with other historical TV shows, is an evidence of the importance of the exercise of "soft power" by the cinema and TV show industry in the Middle East. As it has been highlighted above, Turkey has been investing in cinema production to export its image to the world for a long time now. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have been restrictive when it comes to cinema, not even allowing it within the country in the case of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) for more than 35 years, and they have had few interest on producing and promoting self-made cinema. Now this has dramatically changed. Saudis have an interest in translating their self-conception of matters to the world, and communication is a way of contesting and resisting a dominant culture's encroachment[2] that is being headed by Turkey.

In the words of Yuser Hareb, Genomedia owner(Mamalik al nar's film production company), the series was born from the idea of creating an alternative to the influence that Turkish productions have within Arabs. The producer argues that the Ottoman Empire period is not much of a glorious heritage for Arabs, but more of a "dark time," characterised by repression and criminal actions against Arabs. Turkish historic cinema "adjusts less than 5% to reality," Hareb says, and Mamalik al Nar is intended to break with the Turkish cultural influence in the Middle East by "vindicating Arab history" and stating that Ottomans were neither the protectors of Islam, nor are they the restorers of it.

Dynamics are changing in the region. The Middle East Broadcasting Center (MBC), the large Emirates-based and Saudi-owned average conglomerate that is one of the strongest broadcasting channel in the Arabic speaking world, was in charge of broadcasting in the Arab countries some of the most famous Turkish dramas since 2007, such as the soap opera Gumus, which final episode had 92 million viewers across the region. In March 2018, MBC rejected several Turkish dramas and it even announced an unofficial moratorium on broadcasting any Turkish series. This decision was praised by the Genomedia owner (the producer of Mamalik al nar), Yuser Hareb, pronouncing against those who passively permit the influence of foreigners with their films and series. Furthermore, MBC is also responsible for the broadcasting of Mamalik al nar in the region. The combination of these movements put together can easily portray a deterioration of Turkish-Arab relations.

Egypt also serves as an example of this anti-Turkish trend, when in September 2014, all Turkish series were banned in response to Erdogan's support for the Islamist president Mohammed Morsi (overthrown in July 2013) and his attacks on President Abdelfatah Al-Sisi. This adds to the backing of Turkey of the Muslim Brotherhood and the meddling in Libya to gain regional leadership over the exploration of gas deposits. In short, the backing of Islamist movements constitutes the main argument given when criticising Turkey's "neo-colonialist" aims, which are not completely denied by the Turkish government as it claims the will to be a restorer for the Muslim world.

Double-sided

Ultimately, both the Turkish and the Saudi Arabian sides have the same opinion of what the other is trying to do: influencing the region by their own idiosyncrasy and cultural heritage. It is indeed the crossfire of accusations against one another for influencing and deceiving the audience about the history of the region, especially regarding who should be praised and who condemned.

Turkish and other pro-Erdogan commentators have described Mamalik al nar as an attempt to foment division between Muslims and attacking the Ottoman legacy. Yasin Aktay, an advisor to Erdogan, remarked that there are no Turkish series that attack any Arab country so far, unlike this Saudi series is doing with the former Ottoman Empire by manipulating "historical data for an ideological or political reason". Indeed, it is an attack on "the Ottoman State, but also on contemporary Turkey, which represents it today".

The legacy of the Ottoman Sultanate has been subjected to political and intellectual discussion since medieval times. Specifically, after World War I, when a lot of new Arab nation-states started to consolidate, the leaders of these new-born states called for a nationalist feeling by means of an imperialist discourse, drifting apart Turks and Arabs. It is still today a controversial topic in a region that is blooming and which leadership is being disputed, however -and, perhaps, fortunately-, this ideology does not go beyond the ruling class, and neither the great majority of Arabs see the Ottomans as a nation that invaded and exploited them nor the Turks see Arabs as traitors.

No matter how much Erdogan's Turkey puts the focus on Islam, the big picture of Turkish series is a secular and modern outlook of the region, which has come to be especially interesting to keep up with the region's changing dynamics. That could be overshadowed by salafist movements restricting freedom of speech in what is considered immoral forms of art by some.

All in all, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates are determined to counterbalance Turkey's effort to increase its regional clout through the use of "soft power" instruments by means of reacting to the abundance of Turkish dramas by launching TV series and shows that offer an "Arab approach" to the matter. In any case, it is still to be seen whether these new Arab productions narrating the ancient history of the Arab territories will have or not a success equivalent to the already consolidated Turkish industry.

[1] Manuel Castells. The rise of network society (New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

[2] Thomas K. Nakayama and Raymond J. Krizek. Nakayama and Raymond J. Krizek (1995). Whitness: A strategic rhetoric (Quarterly Journal of Speech, 1995), 81, 291-319.

[Lilia M. Schwarcz and Heloisa M. Starling, Brazil: a biography (discussion: Madrid, 2016), 896 pp.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

Presenting the history of a vast country such as Brazil in a single volume, albeit an extensive one, is no easy task, if one wants to go into sufficient depth. "Brazil. A Biography" (for this review we have used Penguin's English edition, from 2019, somewhat later than the publication of the work in Spain; the original in Portuguese is from 2015) is an account with the appropriate lens. "Brazil is not for beginners", say the two authors in the introduction, expressing with that quotation of a Brazilian musician the way they conceived the book: knowing that they were addressing an audience with generally little knowledge about the country, they had to be able to convey the complexity of national life (of what constitutes a continent in itself) but without making the reading agonising.

Presenting the history of a vast country such as Brazil in a single volume, albeit an extensive one, is no easy task, if one wants to go into sufficient depth. "Brazil. A Biography" (for this review we have used Penguin's English edition, from 2019, somewhat later than the publication of the work in Spain; the original in Portuguese is from 2015) is an account with the appropriate lens. "Brazil is not for beginners", say the two authors in the introduction, expressing with that quotation of a Brazilian musician the way they conceived the book: knowing that they were addressing an audience with generally little knowledge about the country, they had to be able to convey the complexity of national life (of what constitutes a continent in itself) but without making the reading agonising.

The book follows a chronological order; however, the fact of starting with some general considerations and building the first chapters around certain social and political systems generated successively by the sugar cane plantations, the enslavement of the African population and the search for gold means that Brazilian life advances before our eyes without having the sensation of a mere shifting of dates. Later comes the 19th century, which for Hispanics is of interest to see the negative side of the history we know about the Spanish American colonies (in contrast to the Spanish case, during the Napoleonic wars the entire Portuguese Court moved to Rio de Janeiro and independence did not result in various republics, but in a centralised monarchy of its own). And then a 20th century that in Brazil was a good compendium of the political vicissitudes of the contemporary world: from the Estado Novo of Getúlio Vargas, to the military dictatorship and the restoration of democracy.

The work by Schwarcz and Starling, professors at the University of São Paulo and the Federal University of Minas Gerais, respectively, focuses on political processes, but always with the parallel social and cultural processes that occur together in any country. The volume provides a wealth of information and bibliographical references for all of Brazil's historical periods, without disregarding some in favour of others, and the reader can focus on those moments that are of greatest interest to him or her.

Personally, I have been more interested in reading about four periods, relatively distant from each other. On the one hand, the attempts by France and Holland in the 16th and 17th centuries to set foot in Brazil (they were not permanently successful, and both powers had to settle for the Guianas). Then the emergence and consolidation in the 18th century of Minas Gerais as the third vertex of the Brazilian heartland triangle (Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Belo Horizonte). Then the description of the life of a European-style court in the circumstances of the tropical climate (the monarchy lasted until 1889). And finally the experiences of mid-20th century developmentalism, with Juscelino Kubitschek and João Goulart in a tour de force between democratic compromise, presidential personalism and the undercurrents of the Cold War.

Reading this book provides numerous keys to a better understanding of certain aspects of Brazil's behaviour as a country. On the one hand, how the immensity of the territory and the existence of areas that are difficult for the state to reach - the Amazon is a clear example - gives the army an important role as guarantor of the continuity of the nation (the success, perhaps momentary, of Bolsonaro and his appeal to the Armed Forces has to do with this, although this last presidency is no longer included in the book). On the other, how the division of territorial power between mayors and governors generates a multitude of political parties and forces each presidential candidate to articulate multiple alliances and coalitions, sometimes incurring in a "buying and selling" of favours that generally ends up having a cost for the country's institutionality.

The book's essay was completed before the collapse of the Workers' Party government era. That is why the consideration of the governments of Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff is, perhaps, somewhat complacent, as a sort of "end of history": since the end of the military dictatorship in 1985, the country would have evolved in the improvement of its democratic and social life until the time crowned by the PT. The "Lava Jato case" has shown that "history continues".

COMMENT / Sebastián Bruzzone

"We have failed... We should have acted earlier in the face of the pandemic". These are not the words of a political scientist, scientist or journalist, but of Chancellor Angela Merkel herself addressing the 27 other leaders of the European Union on 29 October 2020.

Anyone who has followed the news from March to today can easily realise that no government in the world has been able to control the spread of the coronavirus, except in one country: New Zealand. Its prime minister, the young Jacinda Ardern, closed the borders on 20 March and imposed a 14-day quarantine on New Zealanders returning from overseas. Her "go hard, go early" strategy has yielded positive results compared to the rest of the world: fewer than 2,000 infected and 25 deaths since the start of the health crisis. And the question is: how have they done it? The answer is relatively simple: their unilateral behaviour.

The most sceptical to this idea may think that "New Zealand is an island and has been easier to control". However, it is necessary to know that Japan is also an island and has more than 102,000 confirmed cases, that Australia has had more than 27,000 infected, or that the United Kingdom, which is even smaller than New Zealand, has more than one million infected. The percentage of cases out of the total population of New Zealand is tiny, only 0.04% of its population has been infected.

As the world's states waited for the World Health Organisation (WHO) to establish guidelines for a common response to the global crisis, New Zealand walked away from the body, ignoring its wildly contradictory recommendations, which US President Donald J. Trump called "deadly mistakes" while suspending America's contribution to the organisation. Japanese Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aro went so far as to say that the WHO should be renamed the "Chinese Health Organisation".

The New Zealand case is an example of the weakening of today's multilateralism. Long gone is the concept of multilateral cooperation that gave birth to the United Nations (UN) after the Second World War, whose purpose was to maintain peace and security in the world. The foundations of global governance were designed by and for the West. The powers of the 20th century are no longer the powers of the 21st century: emerging countries such as China, India or Brazil are demanding more power in the UN Security committee and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The lack of common values and objectives between developed and emerging countries is undermining the legitimacy and relevance of last century's multilateral organisations. In fact, China already proposed in 2014 the creation of the Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) as an alternative to the IMF or the World Bank.

The European Union is not spared from the multilateral disaster either because it has been attributed the shared skill in common security matters in subject of public health (TFEU: art. 4.k)). On 17 March, the European committee took the incoherent decision to close external borders with third states when the virus was already inside instead of temporarily and imperatively fail the Schengen Treaty. On the economic front, inequality and suspicion between the debt-prone countries of the North and the South have increased. The refusal of the Netherlands, Finland, Austria and other frugals to the unconditional financial aid required by a country like Spain, which has more official and political cars than the rest of Europe and the United States combined, called into question one of the fundamental principles on which the European Union was built: solidarity.

Europe has been the perfect storm in a sea of uncertainty and Spain, the eye of the hurricane. The European economic recovery fund is a term that overshadows what it really is: a financial bailout. A total of 750 billion euros divided mainly between Italy, Portugal, France, Greece and Spain, which will receive 140 billion euros and will be paid back by our grandchildren's children. It seems fanciful that the first health aid Italy received came from third states and not from its EU partners, but it became a reality when the first planes from China and Russia landed at Fiumicino airport on 13 March. The pandemic is proving to be an examination of conscience and credibility for the EU, a sinking ship with 28 crew members trying to bail out the water that is slowly sinking it.

Leading scholars and politicians confirm that states need multilateralism to respond jointly and effectively to the great risks and threats that have crossed borders and to maintain global peace. However, this idea collapses when it is realised that today's leading figure in bilateralism, Donald J. Trump, is the only US president since 1980 not to have started a war in his first term, to have brought North Korea closer, and to have secured recognition of Israel by Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates.

It is time to shift geopolitics towards updated and consensus-based solutions based on cooperative governance rather than global governance led by obsolete and truly powerful institutions. Globalist multilateralism that seeks to unify the actions of countries with very disparate cultural and historical roots under a single supranational entity to which they cede sovereignty can cause major clashes within the entente, provoke the departure of some of the disgruntled members, the subsequent extinction of the intended organisation and even enmity or a rupture of diplomatic relations.

However, if states with similar values, laws, customary norms or interests decide to come together under a treaty or create a regulatory institution, even while ceding just and necessary sovereignty, the understanding will be much more productive. Thus, a network of bilateral agreements between regional organisations or between states has the potential to create more precise and specific objectives, as opposed to signing a globalist treaty where long letters and lists of articles and members can become smoke and mere declarations of intent as has been the case with the Paris Climate Change Convention in 2015.

This last idea is the true and optimal future of International Office: regional bilateralism. A world grouped in regional organisations made up of countries with similar characteristics and objectives that negotiate and reach agreements with other groups of regions through dialogue, peaceful understanding, the art of diplomacy and binding pacts without the need to cede the soul of a state: sovereignty.

![Joe Biden and Barack Obama in February 2009, one month after arriving at the White House [Pete Souza]. Joe Biden and Barack Obama in February 2009, one month after arriving at the White House [Pete Souza].](/documents/16800098/0/biden-obama-blog.jpg/ad49fcda-889d-4b84-14cc-87cf326fc61c?t=1621883654693&imagePreview=1)

Joe Biden and Barack Obama in February 2009, one month after arriving at the White House [Pete Souza].

COMMENTARY / Emili J. Blasco

This article was previously published, in a somewhat abbreviated form, in the newspaper 'Expansión'.

One of the great mistakes revealed by the US presidential election is to have underestimated the figure of Donald Trump, believing him to be a mere anecdote, and to have disregarded much of his politics as whimsical. In reality, the Trump phenomenon is a manifestation, if not a consequence, of the current American moment, and some of his major decisions, especially in the international arena, have more to do with domestic imperatives than with fickle whimsy. The latter suggests that there are aspects of foreign policy, manners aside, in which Joe Biden as president may be closer to Trump than to Barack Obama, simply because the world of 2021 is already somewhat different from that of the first half of the previous decade.

First, Biden will have to confront Beijing. Obama began to do so, but the more assertive character of Xi Jinping's China has been accelerating in recent years. In the superpower tug-of-war, especially over the dominance of the new technological age, the US has everything at stake vis-à-vis China. It is true that Biden has referred to the Chinese not as enemies but as competitors, but the trade war was already begun by the administration of which he was vice-president and now the objective rivalry is greater.

Nor is the US's withdrawal the result of Trump's madness. Basically it has to do, to simplify somewhat, with the energy independence achieved by the Americans: they no longer need oil from the Middle East and no longer have to be in all the oceans to ensure the free navigation of tankers. America First' has in a way already been started by Obama and Biden will not go in the opposite direction. So, for example, no major involvement in EU affairs and no firm negotiations for a free trade agreement between the two Atlantic markets can be expected.

On the two major achievements of the Obama era - the agreement nuclear deal with Iran sealed by the US, the EU and Russia, and the restoration of diplomatic relations between Washington and Havana - Biden will find it difficult to tread the path then defined. There may be attempts at a new rapprochement with Tehran, but there would be greater coordination against it on the part of Israel and the Sunni world, which are now more convergent. Biden may find that less pressure on the ayatollahs pushes Saudi Arabia towards the atom bomb.

As for Cuba, a return to dissent will be more in the hands of the Cuban government than of Biden himself, who in his electoral loss in Florida has been able to read a rejection of any condescension towards Castroism. Some of the new restrictions imposed by Trump on Cuba may be dismantled, but if Havana continues to show no real willingness to change and open up, the White House will no longer have to continue betting on political concessions to credit .

In the case of Venezuela, Biden is likely to roll back a good part of the sanctions, but there is no longer room for a policy of inaction like Obama's. That administration did not confront Chavismo for two reasons. That Administration did not confront Chavismo for two reasons: because it did not want to upset Cuba, given the secret negotiations it was holding with that country to reopen its embassies, and because the regime's level of lethality had not yet become unbearable. Today, international human rights reports are unanimous on the repression and torture of Maduro's government, and the arrival of millions of Venezuelan refugees in the different countries of the region means that it is necessary to take action on the matter. Here it is to be hoped that Biden will be able to act less unilaterally and, while maintaining pressure, seek coordination with the European Union.

It is often the case that those who come to the White House deal with domestic affairs in their first years and then later, especially in a second term, focus on leaving an international bequest . Due to age and health, the new occupant may only serve a four-year term. Without Obama's idealism of wanting to 'bend the arc of history' - Biden is a pragmatist, a product of the US political establishment - or businessman Trump's rush for immediate gain, it is hard to imagine that his administration will take serious risks on the international stage.

Biden has confirmed his commitment to begin his presidency in January by reversing some of Trump's decisions, notably on climate change and the Paris agreement ; on some tariff fronts, such as the outgoing administration's unnecessary punishment of European countries; and on various immigration issues, especially concerning Central America.

In any case, even if the Democratic left wants to push Biden to the margins, believing that they have an ally in Vice President Kamala Harris, the president-elect can make use of his staff moderation: the fact that in the elections he obtained a better result than the party itself gives him, for the moment, sufficient internal authority. The Republicans have also held their own quite well in the Senate and the House of Representatives, so that Biden comes to the White House with less support on Capitol Hill than his predecessors. That, in any case, may help to reinforce one of the Delaware politician's generally most valued traits today: predictability, something that the economies and foreign ministries of many of the world's countries are eagerly awaiting.

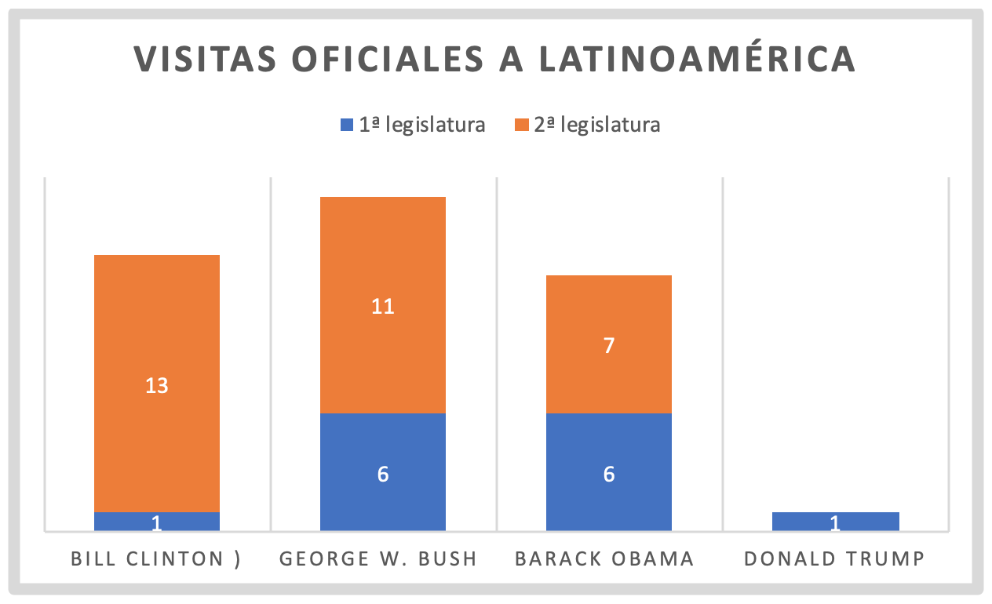

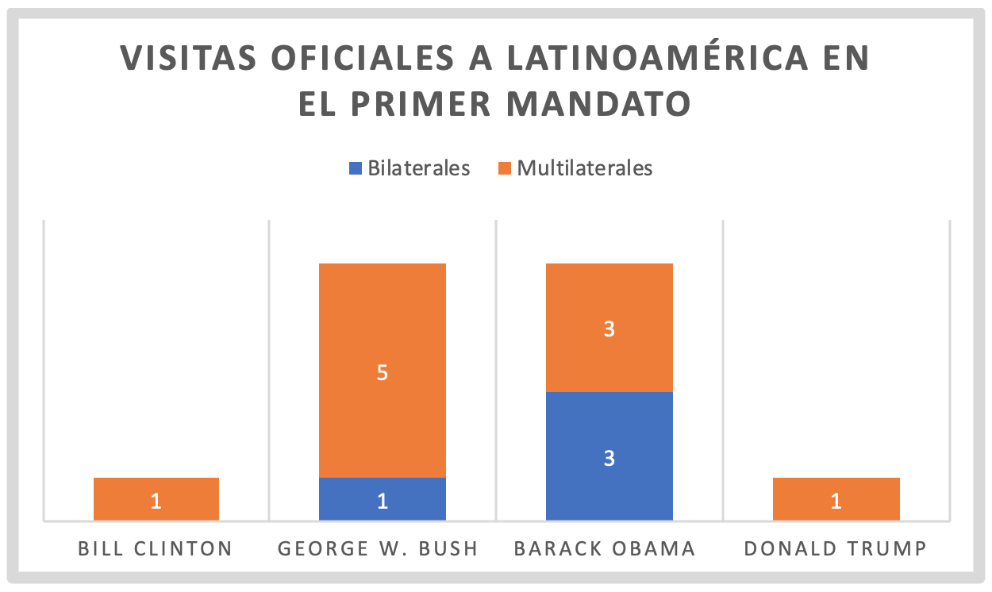

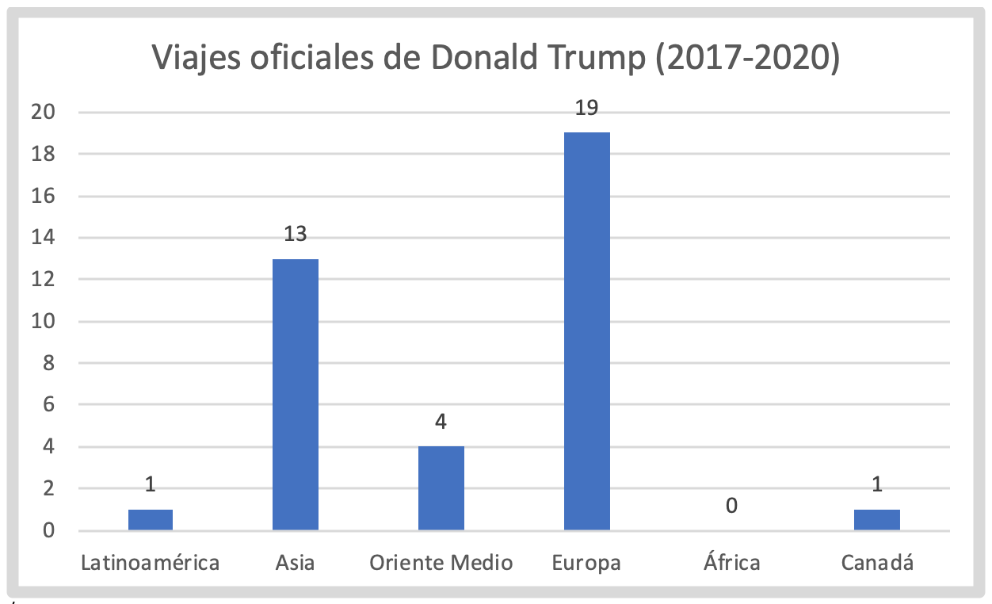

The current president made only one visit, also at the framework of the G-20, compared to the six that Bush and Obama made in their first four years.

International travel does not tell the whole story about a president's foreign policy, but it does give some clues. As president, Donald Trump has only travelled once to Latin America, and then only because the G20 summit he was attending was being held in Argentina. It is not that Trump has not dealt with the region - of course, Venezuela policy has been very present in his management- but the fact that he has not made the effort to travel to other countries on the continent reflects the more unilateral character of his policy, which is not very focused on gaining sympathy among his peers.

![signature in Mexico in 2018 of the free trade agreement between the three North American countries [department of State, USA]. signature in Mexico in 2018 of the free trade agreement between the three North American countries [department of State, USA].](/documents/16800098/0/viajes-trump-blog.jpg/157ee6c8-c573-2e22-6911-3ae54fe8a0a8?t=1621883760733&imagePreview=1)

▲ signature in Mexico in 2018 of the free trade agreement between the three North American countries [department of State, USA].

article / Miguel García-Miguel

With only one visit visit to the region, the US president is the one who has made the fewest official visits since Clinton's first term in office, who also visited the region only once. In contrast, Bush and Obama paid more attention to the neighbouring territory, both with six visits in their first term. Trump focused his diplomatic campaign on Asia and Europe and reserved Latin American affairs for visits by the region's presidents to the White House or his Mar-a-Lago resort.

In reality, the Trump administration spent time on Latin American issues, taking positions more quickly than the Obama administration, as the worsening problem in Venezuela required defining actions. At the same time, Trump has discussed regional issues with Latin American presidents during their visits to the US. There has not, however, been an effort at multilateralism or empathy, going to his meeting in their home countries to deal with their problems there.

Clinton: Haiti

The Democratic president made only one visit to the region during his first term in office: visit . refund After the Uphold Democracy operation to bring Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power, on 31 March 1995 Bill Clinton travelled to Haiti for the transition ceremony organised by the United Nations. The operation had consisted of a military intervention by the United States, Poland and Argentina, with UN approval, to overthrow the military board that had forcibly deposed the democratically elected Aristide. During his second term, Clinton paid more attention to regional affairs, with thirteen visits.

Bush: free trade agreements