Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Security and defence .

Spain sells less defence materiel to Latin American countries than it should, given the volume of trade.

-

2019 saw a recovery in Spanish arms sales to Latin America, surpassing 2018 figures, which were the lowest in a long time.

-

In the last five years, Spain has sold 691.2 million euros worth of defence material to the region, 3.6% of its world arms exports.

-

Mexico (24.8%), Ecuador (22.5%), Brazil (16.1%), Peru (14.4%) and Colombia (8.6%) are the five countries that purchased the most material from Spain in the last five years.

![Airbus NH90 helicopter, final assembly at Airbus Military facilities in Spain [Airbus] [Airbus]. Airbus NH90 helicopter, final assembly at Airbus Military facilities in Spain [Airbus] [Airbus].](/documents/10174/16849987/espana-armas-blog.jpg)

Airbus NH90 helicopter, final assembly at Airbus Military facilities in Spain [Airbus].

report SRA 2020 / Álvaro Fernández[PDF version].

Latin American countries constitute a area of clear commercial interest for Spain. However, despite being the seventh largest arms exporter in the world and therefore particularly active in this sector, Spain sells less defence material to Latin America and the Caribbean than it would be entitled to in terms of its overall export quota to the region.

While between 2014 and 2018 Spain's overall export of products to Latin America remained between 5.3% and 6.5% of its global exports, in the case of the arms sector it was around 3.2% in 2016 and 2017 and fell to 1.06% in 2018. It is to be expected that this minimum percentage will have risen again in 2019, a year for which there is still no official data complete, but in view of those of the first semester it would seem that it will not even be close to 3%.

The explanation for this lower weight of arms exports in Spain's overall exports to Latin America can be found in two facts. One is the lower budget devoted to the purchase of this subject of material by most Latin American countries, compared to some large buyers(in 2018 Spain's first customer was Germany - in turn the fourth largest exporter in the world -, which accounted for 33% of Spanish sales). The other is that Latin American nations have other important market options: the United States, Russia and China (first, second and fifth largest arms exporters in the world; France is the third).

In 2018 there was a significant drop in Spanish defence exports to Latin America, which amounted to 38.3 million euros, well below any of the previous years. The partial data for 2019 indicates a recovery, although without reaching the figures recorded in 2015, when a peak of €239.4 million was reached, or those of the previous years of 2016 and 2017, when they were €130.7 million and €139.3 million, respectively.

The decrease in 2018 corresponds to a lower purchase list from most Latin American customers. Of the five largest customers over the past five years, Colombia was the only one to maintain a similar level of purchases, amounting to €11 million. Colombia and the next largest buyer, Mexico, were the only ones to slightly increase their imports in 2017, although they were lower than in previous years. The reduction was significant for the next two customers in 2018, Brazil and Peru. This year marked a further reduction in imports from Ecuador, which has continuously cut its order book from Spain over the last five years.

The figures considered in this article only take into account defence material, not other subject material, which the administrative office considers separately, such as riot control material, hunting and sporting weapons, as well as dual-use technology products.

General and Latin American sales

Spain has around 130 companies dedicated to the arms sector. These include Airbus Military, Navantia and Indra, which are among the world's top 100 defence and security companies. Most of the sector are private companies, although there are some unique cases of public ownership, such as Navantia, dedicated to shipbuilding, both civil and military, created in 2005 when the assets of another public company, business , group IZAR, were spun off.

According to the official data of the administrative office of State for Trade, the issue of defence material exports has been increasing notably over the last few years. More than half of Spanish arms exports during 2018 and the first semester of 2019 were destined for countries belonging to NATO or the European Union. In 2017, exports exceeded 4.3 billion euros, after several years of increases in this market. In contrast, arms worth €3,720.4 million were sold in 2018, which was 14.4% less. In the first semester of 2019, however, an improvement was recorded, reaching €2,413 million, an increase of 41.5% compared to the same period last year.

In terms of trade with Latin America, between 2014 and 2018 Spain sold €691.2 million worth of military equipment to the region, representing 3.6 per cent of Spain's total arms exports of €19,042 million.

Over the five years as a whole, the leading importer was Mexico, which with purchases worth 171.4 million euros (of which 140.9 million euros corresponded to 2015 alone), acquired a quarter (24.8 per cent) of the defence materiel sold by Spain to Latin America over the five-year period. The second most important country was Ecuador, with 155.7 million and 22.5 per cent (slightly more than half -85.9 million- were purchases made in 2014 alone). It is followed by Brazil, which made more regular purchases over this time, with 111.8 million and 16.1%); Peru, with 99.5 million and 14.4% (the largest amount -78.4 million- was executed in 2017), and Colombia, with 59.5 million and 8.6%.

Some countries

Mexico has been the leading purchaser of Spanish defence material in the last five years (2014 and 2018) due to purchases made in 2015, when it acquired four transport aircraft, worth 127.2 million euros. In 2018 it only imported €10.1 million worth of parts, pieces and spare parts for Spanish-made aircraft, engine equipment for an aircraft derived from a European cooperation programme and instruments for an air surveillance system.

Brazil is one of the countries with the greatest diversity in the destination of its imports. In recent purchases, 19.7% went to private business , 74.2% to the Armed Forces and the remaining 5.9% to individuals. In 2018, it purchased 7.9 million euros worth of pistols, rifles and magazines for private individuals, as well as day sights, armoured vehicle parts, and Spanish and US-made aircraft parts for the Armed Forces.

Colombia imported in 2018 a total of 11 million euros in spare parts for the maintenance of artillery howitzers, artillery ammunition, spare parts for Spanish and US-made armoured vehicles, and parts for Spanish-made transport aircraft.

Until a few years ago, Venezuela was an important client for the Spanish arms industry. However, following the authoritarian drift taken by Nicolás Maduro's government, relations in this field have weakened. As recently as 2015, Spain sold 15.3 million euros worth of defence material to Maduro, in operations that were shrouded in controversy as some of the exported equipment could be used in the severe repression carried out against its citizens. Since then, with the increase in tensions between the Chavista regime and the United States or the European Union, a series of restrictions have been placed on the export of this subject material to Venezuela. Thus, sales went from having a value of 3.3 million euros in 2017 to just 44,000 euros in 2018, corresponding to payment for spare parts and parts for the modernisation of French-made armoured vehicles, in a transaction that was approved before the trade restrictions of this subject imposed by the EU.

The official data provided by administrative office distinguishes between authorised exports and realised exports. Authorisations do not always materialise in actual sales and sometimes these are executed in subsequent years. The difference is particularly notable in Venezuela, whose political status forced the restriction of exports to that country. In 2018, Spain suspended four licences already approved for Caracas, relating to helicopter maintenance and the provision of electro-optical supplies and systems. In addition, extensions to contracts for the modernisation of battle tanks were denied.

Bolivia and Nicaragua have stopped buying defence materiel from Spain: while between 2014 and 2018 they made no purchases, between 2007 and 2013 they imported 1.5 million and 62,000 euros, respectively.

Cuba, which had a peak in purchases in 2015 at €208,080, in 2018 spent €20,600 on pistols and pistol barrels for the police.

ANALYSIS / Salvador Sánchez Tapia [Brigadier General (Res.)].

The COVID-19 pandemic that Spain has been experiencing since the beginning of 2020 has brought to light the commonplace, no less true for having been repeated, that the concept of national security can no longer be limited to the narrow framework of military defence and demands the involvement of all the nation's capabilities, coordinated at the highest possible level which, in Spain's case, is none other than that of the Presidency of the Government through the National Security committee .[1]

Consistent with this approach, our Armed Forces have been directly and actively involved in a health emergency that is a priori far removed from the traditional missions of the nation's military arm. This military contribution, however, responds to one of the missions entrusted to the Armed Forces by the Organic Law of National Defence, in addition to a long tradition of military support to civil society in the event of catastrophes or emergencies. [2] In its execution, units of the three armies have carried out tasks as varied and apparently unrelated to their natural activity as the disinfection of old people's homes or the transfer of corpses between hospitals and morgues.

This status has stirred up a certain discussion in specialised and professional circles about the role of the armed forces in present and future security scenarios. From different angles, some voices are calling for the need to reconsider the missions and dimensions of armies in order to align them with these new threats, not with the classic war between states.

internship This view seems to be supported by the apparently empirical observation of the current absence of conventional armed conflicts - understood as those that pit armies with conventional means against each other manoeuvring on a battlefield - between states. Based on this reality, it is concluded that this form of conflict is practically banished, being little more than a historical relic replaced by other less conventional and less "military" threats such as pandemics, terrorism, organised crime, fake news, disinformation, climate change or cyber threats.

The corollary is obvious: it is necessary and urgent to rethink the missions, dimensions and equipment of the Armed Forces, as their current configuration is designed to confront outdated conventional threats, and not for those that are emerging in the present and future security scenario.

A critical analysis of this idea sample, however, paints a somewhat more nuanced picture. From a purely chronological point of view, the still unfinished Syrian civil war, admittedly complex, is closer to a conventional model than to any other subject and, of course, the capabilities with which Russia is making its influence felt in this war by supporting the Assad regime are fully conventional. In 2008, Russia invaded Georgia and occupied South Ossetia and Abkhazia in a conventional offensive operation. In 2006, Israel faced a hybrid enemy in South Lebanon in the form of Hezbollah - indeed, this was the model chosen by Hoffman as the prototype for the term "hybrid" - which combined elements of irregular warfare with fully conventional ones. [3] Earlier still, in 2003, the US invaded Iraq in a massive armoured offensive.[4]

If the case of Syria is eliminated as doubtfully classifiable as conventional warfare, it can still be argued that the last conflict of this nature - which, moreover, involved territorial gain - took place only twelve years ago; a short enough period of time to think that conclusions can be drawn that conventional warfare can be dismissed as a quasi-extinct procedure . In fact, the past has recorded longer periods than this without significant confrontation, which might well have led to similar conclusions. In Imperial Roman times, for example, the Antonine era (96-192 AD), saw a long period of internal Pax Romana briefly disrupted by Trajan's campaigns in Dacia. More recently, after Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo (1815), the Central Powers of Europe experienced a long period of peace lasting no less than thirty-nine years. [5] Needless to say, the end of both periods was marked by the return of war to the foreground.

It can be argued that status is now different, as humanity today has developed a moral rejection of war as a destructive and therefore unethical and undesirable exercise. This distinctly Western-centric - or, if you prefer, Eurocentric - stance takes the part for the whole and assumes this view to be unanimously shared globally. However, the experience of the Old Continent, with a long history of destructive wars between its states, a highly ageing population, and little appetite to remain a relevant player in the international system, may not be shared by everyone.

Western rejection of war may, moreover, be more apparent than real, being directly related to the interests at stake. It is conceivable that, faced with an immediate threat to its survival, any European state would be willing to go to war, even at the risk of becoming a pariah ostracised by the international system. If, at that point, such a state had sacrificed its traditional military muscle in favour of fighting more ethereal threats, it would have to pay the price associated with such a decision. Bear in mind that states choose their wars only up to a point, and may be forced into them, even against their will. As Trotsky said, "you may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you".

The analysis of the historical periods of peace referred to above suggests that, in both cases, they were made possible by the existence of a power moderator stronger than that of the political entities that made up the Roman Empire and post-Napoleonic Europe. In the first case, this power would have been that of Rome itself and its legions, sufficient to guarantee the internal order of the empire. In the second, the European powers, at odds for many reasons, nevertheless stood united against France in the face of the possibility that the ideas of the French Revolution would spread and undermine the foundations of the Ancien Régime.

Today, although it is difficult to find a verifiable cause-effect relationship, it is plausible to think that this "pacifying" force is provided by American military power and the existence of nuclear weapons. Since the end of World War II, the United States has provided an effective security umbrella under whose protection Europe and other regions of the world have been spared the scourge of war on their territories, developing feelings of extreme rejection of any form of war.

On the basis of its unrivalled military might, the United States - and we with it - have been able to develop the idea, supported by the facts, that no other power will be so suicidal as to engage in open conventional warfare. The conclusion is clear: conventional war - against the United States, I might add - is, at internship, unthinkable.

This conclusion, however, is not based on a moral preference, nor on the conviction that other forms of warfare or threat are more effective, but simply on the realisation that, faced with America's enormous conventional power, one can only seek asymmetry and confront it by other means. To paraphrase Conrad Crane, "there are two kinds of enemy: the asymmetrical and the stupid".[6]

In other words, classical military power is a major deterrent that financial aid helps explain the leave recurrence of conventional warfare. Not surprisingly, even authors who preach the end of conventional war advocate that the United States should retain its conventional warfare capability.[7]

From North America, this idea has permeated the rest of the world, or at least the European cultural sphere, where it has become a truism that, under the guise of incontestable reality, obviates the possibility of a conventional war being initiated by the United States - as happened in 2003 - or between two nations of the world, or within one of them, in areas where armed conflict continues to be acceptable tool .

In an exercise in cynicism, one might say that such a possibility does not change anything, because it is none of our business. However, in today's interconnected world, there will always be the possibility that we will be forced to intervene for ethical reasons, or that our security interests will be affected by events in countries or regions a priori geographically and geopolitically distant from us, and that, probably hand in hand with our allies, we will be involved in a classic war.

While still in place, the commitment of US military power to Western security is under severe strain as America is increasingly reluctant to take on this role alone, and demands that its partners do more for its own security. We are not suggesting here that the transatlantic link will break down immediately. It seems sensible, however, to think that maintaining it comes at a cost to us that could drag us into armed conflict. It is also worth asking what might happen if one day the US commitment to our security were to lapse and we had transformed our armed forces to focus exclusively on the "new threats", dispensing with a conventional capability that would undoubtedly lower the cost that someone would have to incur if they decided to attack us with such means subject .

A final consideration has to do with what appears to be China's unstoppable rise to the role of major player in the International System, and with the presence of an increasingly assertive Russia, which is demanding to be considered a major global power once again. Both nations, especially the former, are clearly undergoing a process of rearmament and modernisation of their military, conventional and nuclear capabilities that does not exactly augur the end of conventional warfare between states.

To this must be added the effects of the pandemic, which are still difficult to glimpse, but among which there are some worrying aspects that should not be overlooked. One of these is China's effort to position itself as the real winner of the crisis, and as the international power of reference letter in the event of a repeat of the current global crisis. Another is the possibility that the crisis will result, at least temporarily, in less international cooperation, not more; that we will witness a certain regression of globalisation; and that we will see the erection of barriers to the movement of people and goods in what would be a reinforcement of realist logic as a regulatory element of International Office.

In these circumstances, it is difficult to predict the future evolution of the "Thucydides trap" in which we currently find ourselves as a result of China's rise. It is likely, however, to bring with it greater instability, with the possibility of escalation into a conventional subject conflict, whether between great powers or through proxies. In such circumstances, it seems advisable to be prepared for the most dangerous scenario of open armed conflict with China to materialise, as the best way to avoid it, or at least to deal with it in order to preserve our way of life and our values.

Finally, one cannot overlook the capacity of many of the "new threats" - global warming, pandemics, etc. - to generate or at least catalyse conflicts, which can indeed lead to a war that could well be conventional.

From all of the above it can be concluded, therefore, that if it is true that the recurrence of conventional warfare between states is minimal nowadays, it seems risky to think that it might be put away in some obscure attic, as if it were an ancient relic. However remote the possibility may seem, no one is in a position to guarantee that the future will not bring conventional war. Neglecting the ability to defend against it is therefore not a prudent option, especially given that, if needed, it cannot be improvised.

The emergence of new threats such as those referred to in this article, perhaps more pressing, and many of them non-military or at least not purely military, is undeniable, as is the need for the Armed Forces to consider them and adapt to them, not only to maximise the effectiveness of their contribution to the nation's effort against them, but also as a simple matter of self-protection.

In our opinion, this adaptation does not entail abandoning conventional missions, the true raison d'être of the Armed Forces, but rather incorporating as many new elements as necessary, and ensuring that the armies fit into the coordinated effort of the nation, contributing to it with the means at their disposal, considering that, in many cases, they will not be the first response element, but rather a support element.

This article does not argue - it is not its goal- either for or against the need for Spain to rethink the organisation, size and equipment of its armed forces in light of the new security scenario. Nor does it enter into the question of whether it should do so unilaterally, or at agreement with its NATO allies, or by seeking complementarity and synergy with its European Union partners. Understanding that it is up to citizens to decide what armed forces they want, what they want them for, and what effort in resources they are willing to invest in them, what this article postulates is that national security is best served if those who have to decide, and with them the armed forces, continue to consider conventional warfare, enriched with a multitude of new possibilities, as one of the possible threats the nation may have to face. Redefining the adage: Si vis pacem, para bellum etiam magis.[8]

[1] Law 36/2015, on National Security.

agreement [2] According to article 15. 3 of Organic Law 5/2005 on National Defence, "The Armed Forces, together with the State Institutions and Public Administrations, must preserve the security and well-being of citizens in cases of serious risk, catastrophe, calamity or other public needs, in accordance with the provisions of current legislation". These tasks are often referred to as "support to civil society". This work consciously avoids using that terminology, as it obviates that this is what the Armed Forces always do, even when fighting in an armed conflict. It is more correct to add the qualifier "in the event of a disaster or emergency".

[3] Frank G. Hoffman. Conflict in the 21st Century; The Rise of Hybrid Wars, Arlington, VA: Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2007. On the conventional aspect of Israel's 2006 war in Lebanon see, for example, 34 Days. Israel, Hezbollah, and the War in Lebanon, London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009.

[4] Saddam's response contained a significant irregular element but, by design, relied on the Republican National Guard Divisions, which offered weak armoured and mechanised resistance.

[5] Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 536. This calculation excludes peripheral Spain and Italy, which did experience periods of war in this period.

[6] Dr. Conrad C. Crane is . Crane is Director of the Historical Services of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and principal author of the celebrated "Field guide 3-24/Marine Corps Warfighting Publication 3-33.5, Counterinsurgency. "

[7] Jahara Matisek and Ian Bertram, "The Death of American Conventional Warfare," Real Clear Defense, November 6th, 2017. (accessed May 28, 2020).

[8] "If you want peace, prepare even more for war".

The bi-national Colombian-Venezuelan guerrilla character provides the Maduro regime with another shock force in the face of external military harassment or a coup.

-

The ELN has reached some 2,400 fighters between the two countries; its main funding now comes from illicit businesses in Venezuela, such as drugs and illegal mining.

-

FARC dissidents number at least 2,300; the group with the greatest projection is the one led in Venezuela by Iván Márquez, former FARC leader issue two.

-

Elenos' and ex-FARC cooperate operationally in certain activities promoted by the Maduro regime, but their future organic convergence is unclear.

![FARC dissidents led by Ivan Marquez announce their return to arms, August 2019 [video image]. FARC dissidents led by Ivan Marquez announce their return to arms, August 2019 [video image].](/documents/10174/16849987/sra-2020-eln-exfarc-blog.jpg)

FARC dissidents led by Iván Márquez announce their return to arms, August 2019 [video image].

report SRA 2020 / María Gabriela Farjardo[PDF version].

The consolidation of the two main Colombian guerrilla groups - the ELN and some remnants of the former FARC - as active forces also in Venezuela, thus articulating themselves as Colombian-Venezuelan groups, constitutes one of the main notes of 2019 in the field of regional security in the Americas.

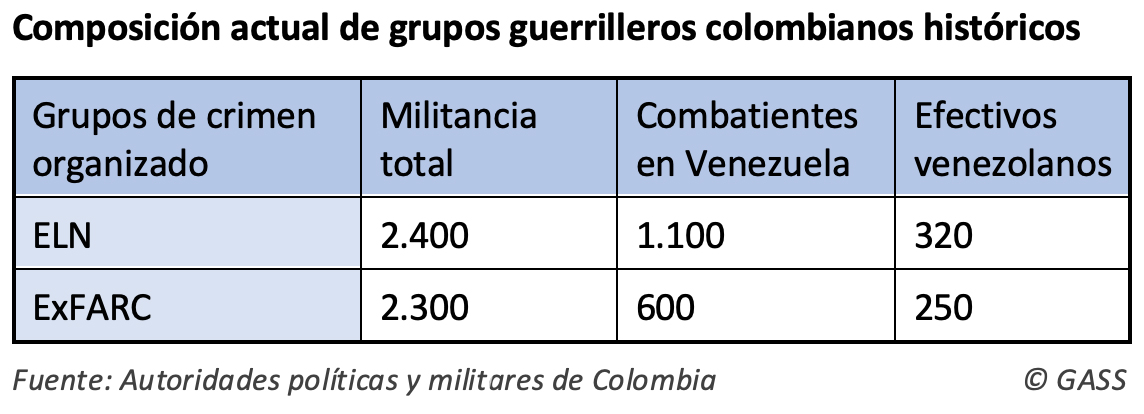

Both groups are said to have around 1,700 troops in Venezuela (two thirds of them from the ELN), of which a third (570) are said to be recruited from among Venezuelans. Used by the Chavista regime for guerrilla training of its irregular forces and as a shock force in the event of external military harassment or a coup, the ELN and ex-Farc are involved in drug trafficking, smuggling and the extraction of gold and other illegal mining, both in areas close to the border with Colombia, where they have operated for many years, and in the Venezuelan interior, such as the mining-rich states of Amazonas and Bolívar.

Following the agreement peace agreement signed between the government of Juan Manuel Santos and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in November 2016, the National Liberation Army (ELN) began a process of expansion that allowed it to fill the vacuum left by the FARC in various illicit activities, although its estimated issue of 2,400 troops is a far cry from the more than 8,000 that the FARC had at the time of its demobilisation. Although it has had to compete with FARC remnants that are still active as mafia elements, the ELN has become Colombia's main guerrilla force, also focused on organised crime. The ELN's 17 January 2019 attack on the Police Cadet School in Bogotá, in which 22 people were killed, marked the end of an agonising peace dialogue with the government and a flight forward as a criminal organisation.

In the process, the ELN has also been establishing itself in Venezuela, not only in border areas and as a place of refuge and hiding place as before, but also in other parts of the neighbouring country and as an area of activity. The same has happened with the FARC dissidents led by Iván Márquez, Jesús Santrich and El Paisa, who on 29 August announced their return to arms, in a video presumably recorded in Venezuela. The interest of Nicolás Maduro's regime in having the help of such armed elements has meant that the ELN and the ex-FARC of Márquez, who was the FARC's issue 2 and its chief negotiator in the peace negotiations held in Havana, have become bi-national groups, also recruiting Venezuelans.

ELN

The growing presence of these groups in Venezuela has been reported by the Colombian authorities. The commander of the Armed Forces, General Luis Navarro, indicated in mid-year that some 1,100 ELN members (just over 40 per cent of the organisation's 2,400 fighters, although other sources consider this total figure to be leave ) were taking refuge in Venezuela, and that group had at least 320 Venezuelan citizens in its ranks.

Meanwhile, during his visit to the UN General Assembly in late September, President Iván Duque raised the ELN's presence in Venezuela to 1,400 troops. Duque indicated that there were 207 geographical points controlled by the ELN on Venezuelan soil, including several training camps and twenty airstrips for drug trafficking, as documented in a controversial dossier that was not released to the public because it contained some test erroneous photographs.

A few days earlier, Foreign Minister Carlos Holmes Trujillo had told the OAS about the location of ELN fronts and FARC dissidents in Venezuela and referred to their close connections with the Chavista regime. "The links would be with members of the armed forces, the national guard, military intelligence, as well as irregular groups such as the Bolivarian Liberation Force," he said.

Other details were investigated by the Fundación Ideas para la Paz (FIP), which in its report stated that the ELN finances itself through criminal activities such as extortion and maintains control of gasoline smuggling and mining in several regions of Colombia and Venezuela. In Venezuelan territory, with a presence in at least twelve of its 24 states, it controls gold mines in Bolivar state, hundreds of kilometres from the Colombian border, and coltan mining activities in Amazonas state. According to information attributed to Colombian intelligence, these illicit activities account for 70 percent of their profits. source Thus, the ELN's base of operations in Venezuela is currently the largest source of income for the insurgent group .

FARC dissidents

As for FARC dissidents, Colombian government sources put the number of FARC dissidents at around 2,300 in mid-2019 (including non-demobilised elements, others who have returned to arms and new recruits). While this is close to the figure offered for the ELN, it should be borne in mind that FARC dissidents are atomised.

Some 600 of them are reportedly in Venezuela, including some 250 Venezuelans who have joined their ranks (almost 10 per cent of their total strength). Although these are separate groups that operate on their own, most attention has been given to the one led by Iván Márquez, due to its coordination with the Maduro regime. One episode involving this group was the alleged assassination attempt in Colombia on Rodrigo Londoño, who led the FARC as Timochenko and who has remained loyal to the peace accords. Londoño accused Márquez and El Paisa of ordering the action, foiled by Colombian security forces and unveiled in January 2020, so that other ex-guerrillas would return to arms as they ran out of leadership in civilian life.

Internal documentation of the Venezuelan secret services published by Semana reveals the close relationship between the Maduro government, the ELN and the ex-FARCpartnership . "The regime went from hiding fugitive guerrillas in the early 2000s to serving as the headquarters of operations for these groups. Not only do they prepare militarily, but they also train the militias and the so-called colectivos in guerrilla warfare tactics and strategies," the weekly said.

All this is producing an operational convergence in Venezuela between the ELN and the ex-FARC. However, status does not necessarily lead to a merger of the two groups, which in Colombia maintain their differences, further encouraged by the aspirations of the different criminal groups into which the FARC dissidents have split, and which are referred to in the plural for a reason.

signature On the other hand, the implementation of the Peace Accords was framed in 2019 in a growing climate of insecurity caused by the murder during the year of 77 former FARC guerrillas (173 since the peace agreement was signed in 2016) and 86 local social leaders, according to the report of the UN's University Secretary, António Guterres. Colombian organisations put the latter figure higher, such as the high school of programs of study for development and Peace(Indepaz), which reports 282 homicides, often linked to the attempt to replace coca with legal crops in regions where drug trafficking is active. In any case, this is a decrease compared to 2018, something that can be attributed to the fact that the new territorial distribution of armed groups has already been consolidated and they have less effective resistance.

US Southern Command highlights Iranian interest in consolidating Hezbollah's intelligence and funding networks in the region

-

Throughout 2019, Rosneft tightened its control over PDVSA, marketing 80% of production, but US sanctions forced it to leave the country.

-

The arrival of Iranian Revolutionary Guard troops comes amid a US naval and air deployment in the Caribbean, not far from Venezuelan waters.

-

The Iranians, once again beset by Washington's sanctions, return to the country that helped them circumvent the international siege during the era of the Chávez-Ahmadinejab alliance.

![Nicolás Maduro and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at meeting in Tehran in 2015 [Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency]. Nicolás Maduro and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at meeting in Tehran in 2015 [Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency].](/documents/10174/16849987/sra-2020-venezuela-iran-blog.jpg)

▲ Nicolás Maduro and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at a meeting in Tehran in 2015 [Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency].

report SRA 2020 / Emili J. Blasco [PDF version].

financial aid In a short period of time, Venezuela has gone from depending on Chinese loans to relying on the Russian energy sector (as was particularly evident in 2019) and then to asking for the help of Iranian oil technicians (as was seen at the beginning of 2020). If the Chinese public loans were supposed to keep the country running, Rosneft's aid was only intended to save the national oil company, PDVSA, while the Iranian Revolutionary Guard's financial aid only aims to reactivate some refineries. Whoever assists Venezuela is getting smaller and smaller, and purpose is getting smaller and smaller.

In just ten years, China's big public banks granted 62.2 billion dollars in loans to the Venezuelan government. The last of the 17 loans came in 2016; since then Beijing has ignored the knocks Nicolás Maduro has made on its door. Although since 2006 Chavismo had also received credits from Moscow (some $17 billion for the purchase of arms from Russia itself), Maduro turned to pleading with Vladimir Putin when the Chinese financial aid ended. Unwilling to give any more credit, the Kremlin articulated another way of helping the regime while ensuring immediate benefits. Thus began Rosneft's direct involvement in various aspects of the Venezuelan oil business, beyond the specific exploitation of certain fields.

This mechanism was particularly relevant in 2019, when the progressive US sanctions on Venezuela's oil activity began to have a major effect. To circumvent the sanctions on PDVSA, Rosneft became a marketer of Venezuelan oil, controlling the marketing of most of the total production (between 60 and 80 per cent).

Washington's threat to punish Rosneft also led the company to shift its business to two subsidiaries, Rosneft Trading and TNK Trading International, which in turn left the business when the US pointed the finger at them. Although Rosneft generally serves the Kremlin's geopolitical interests, the fact that it is owned by BP or Qatari funds means that the company does not so easily risk its bottom line.

The departure of Rosneft, which also saw no economic sense in continuing its involvement in reactivating Venezuela's refineries, whose paralysis has plunged the country into a generalised lack of fuel supply to the population, left Maduro with few options. The Russians abandoned the Armuy refinery at the end of January 2020, and the following month Iranians were already trying to get it up and running again. Within weeks, Iran's new involvement in Venezuela became public: Tarek el Assami, the Chavista leader with the strongest connections to Hezbollah and the Shia world, was appointed oil minister in April, and in May five cargo ships brought fuel oil and presumably refining machinery from Iran to Venezuela.

The supply did not solve much (the gasoline was barely enough for a few weeks' consumption) and the Iranian technicians, at least some of them led by the Revolutionary Guard, were unlikely to be able to fix the refining problem. Meanwhile, Tehran was getting substantial shipments of gold in return for its services (nine tonnes, according to the Trump Administration). The Iranian airline Mahan, used by the Revolutionary Guards in their operations, was involved in the transports.

Thus, suffocated by the new outline sanctions imposed by Donald Trump, Iran returned to Venezuela in search of economic oxygen and also of political partnership vis-à-vis Washington, as when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad allied with Hugo Chávez to alleviate the restrictions of the first sanctions regime that the Islamic nation suffered.

US naval and air deployment

Iran's "interference" in the Western Hemisphere had already been mentioned, among the list of risks to regional security, in the appearance of the head of the US Southern Command, Admiral Craig Faller, on Capitol Hill in Washington (in January he went to the Senate and in March to the House of Representatives, with the same written speech ). Faller referred in particular to Iran's use of Hezbollah, whose presence on the continent has been aided by Chavismo for years. According to the admiral, this Hezbollah-linked activity 'allows Iran to gather intelligence and carry out contingency planning for possible retaliatory attacks against the United States and/or Western interests'.

However, the novelty of Faller's speech lay in two other issues. On the one hand, for the first time the head of the Southern Command placed China's risk ahead of Russia's, in a context of growing rivalry between Washington and Beijing, which is also manifested in the positioning of Chinese investments in strategic infrastructure works in the region.

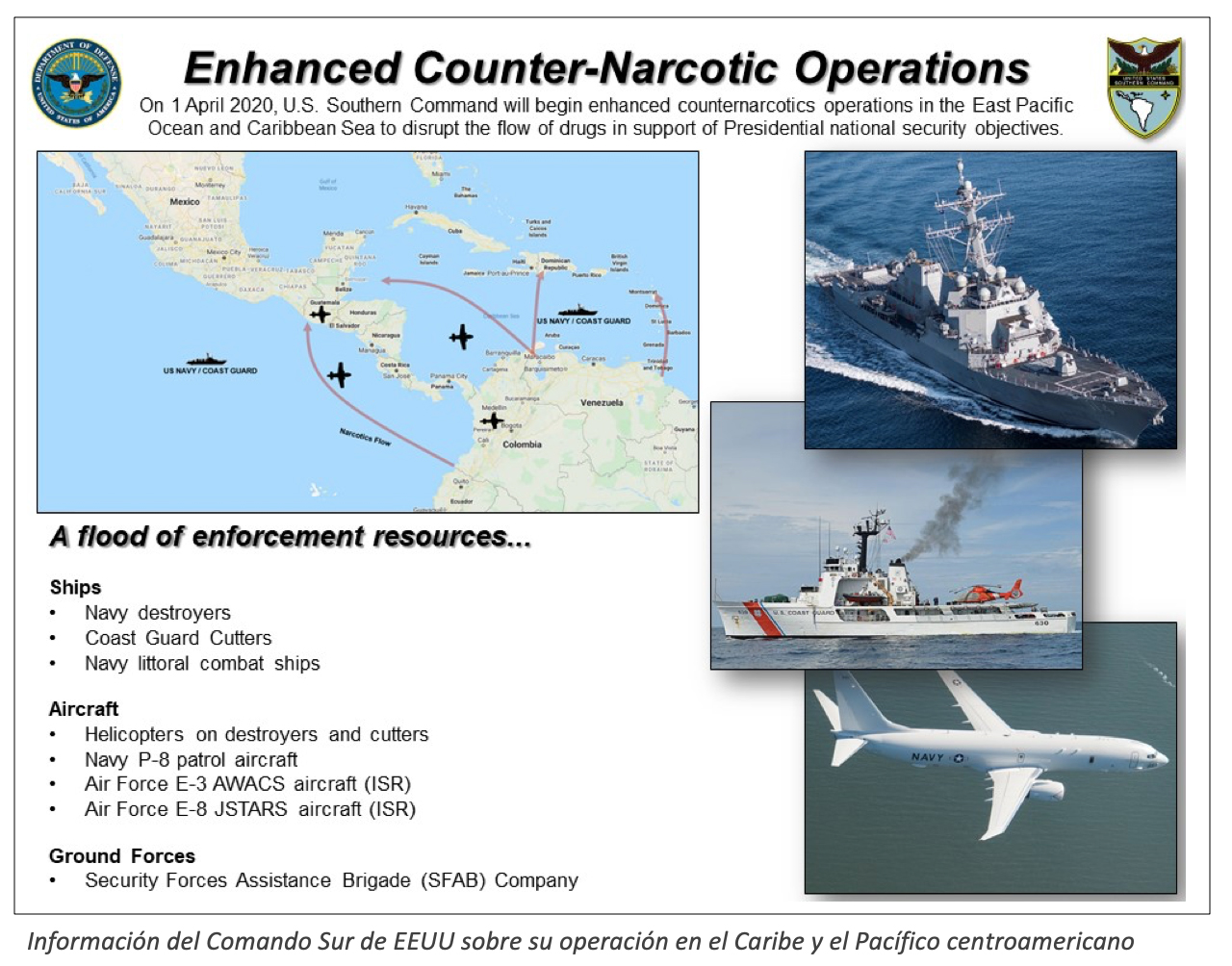

On the other hand, he announced a forthcoming 'increased US military presence in the hemisphere', something that began to take place at the end of March 2020 when US ships and aircraft were deployed in the Caribbean and the Pacific to reinforce the fight against drug trafficking. In the context of its speech, this increased military activity in the region was understood as a necessary notice towards extra-hemispheric countries.

"Above all, what matters in this fight is persistent presence," he said, "we have to be present on the field to compete, and we have to compete to win. Specifically, he proposed more joint actions and exercises with other countries in the region and the "recurring rotation of small special operations forces teams, soldiers, sailors, pilots, Marines, Coast Guardsmen and staff National Guard to help us strengthen those partnerships".

But the arrival of US ships close to Venezuelan waters, just days after the announcement on 26 March from New York and Miami of the opening of a macro-court case for drug trafficking and other crimes against the main Chavista leaders, including Nicolás Maduro and Diosdado Cabello, gave this military deployment the connotation of a physical encirclement of the Chavista regime.

That deployment also gave some context to two other developments shortly thereafter, offering misleading readings: the failed Operation Gideon on 3 May by a group group of mercenaries who claimed they intended to infiltrate the country for Maduro (the increased transmission capabilities acquired by the US in the area, thanks to its manoeuvres, were not used in principle in this operation), and the arrival of the Iranian ships at the end of the month (the US deployment raised suspicions that Washington could intercept the ships' advance, which did not happen).

Regional security in the Americas has been the focus of concern over the past year in Venezuela. We also review Russia and Spain's arms sales to the region, Latin America's presence in peacekeeping missions, drugs in Peru and Bolivia, and homicides in Mexico and Brazil.

![Igor Sechin, director Rosneft executive, and Nicolás Maduro, in August 2019 [Miraflores Palace]. Igor Sechin, director Rosneft executive, and Nicolás Maduro, in August 2019 [Miraflores Palace].](/documents/10174/16849987/sra-2020-resumen-ejecutivo-blog.jpg)

▲ Igor Sechin, director Rosneft executive, and Nicolás Maduro, in August 2019 [Miraflores Palace].

report SRA 2020 / summary executive[PDF version].

Throughout 2019, Latin America had several hotspots of tension - violent street protests against economic measures in Quito, Santiago de Chile and Bogotá, and against political decisions in La Paz and Santa Cruz, for example - but as these conflicts subsided (in some cases, only temporarily), the constant problem of Venezuela as the epicentre of insecurity in the region re-emerged.

With Central American migration to the United States reduced to a minimum by the Trump administration's restrictive measures, it has been Venezuelan migrants who have continued to fill the roadsides of South America, moving from one country to another, and now number more than five million refugees. The difficulties that this population increase entails for the host countries led several of them to increase their pressure on the government of Nicolás Maduro, approving in the OAS the activation of the Inter-American Reciprocal Treaty of attendance (TIAR). But that did not push Maduro out of power, nor did the assumption in January 2019 by Juan Guaidó of the position as president-in-charge of Venezuela (recognised by more than fifty countries), the failed coup a few months later or the alleged invasion of Operation Gideon in May 2020.

While Maduro may appear stabilised, the geopolitical backdrop has been shifting. The year 2019 saw Rosneft gain a foothold in Venezuela as an arm of the Kremlin, once China had stepped back as a credit provider. The risk of not recovering everything it had borrowed meant that Russia acted through Rosneft, benefiting from trading up to 80 per cent of the country's oil. However, US sanctions finally forced the departure of the Russian energy company, so that in early 2020 Maduro had no other major extra-hemispheric partner to turn to than Iran. The Islamic republic, itself subject to a second sanctions regime, thus returned to the close relationship it had maintained with Venezuela in the first period of international punishment, cultivated by the Chávez-Ahmadinejad tandem.

This Iranian presence is closely watched by the United States (coinciding with a deployment of the Southern Command in the Caribbean), which is always alert to any boost that Hezbollah - an Iranian proxy - might receive in the region. In fact, 2019 marked an important leap in the disposition of Latin American countries against this organisation, with several of them classifying it as a terrorist organisation for the first time. Argentina, Paraguay, Colombia and Honduras approved such a declaration, following the 25th anniversary in July of the AMIA bombing attributed to Hezbollah. Brazil and Guatemala pledged to do so shortly. Several of these countries have drawn up lists of terrorist organisations, which allows them to pool their strategies.

The destabilisation of the region by status in Venezuela has a clear manifestation in the reception and promotion of Colombian guerrillas in that country. issue In August, former FARC leader Iván Márquez and some other former leaders announced, presumably from Venezuelan territory, their return to arms. Both this dissident core of the FARC and the ELN had begun to consolidate at the end of the year as Colombian-Venezuelan groups, with operations not only in the Venezuelan border area, but also in the interior of the country. Both groups together have some 1,700 troops in Venezuela, of which almost 600 are Venezuelan recruits, thus constituting another shock force at Maduro's service.

Russia's exit from Venezuela comes at a time when Moscow is apparently less active in Latin America. This is certainly the case in the field of arms sales. Russia, which had become a major exporter of military equipment to the region, has seen its sales decline in recent years. While during the golden decade of the commodity boom several countries spent part of their significant revenues on arms purchases (which also coincided with the spread of the Bolivarian tide, better linked to Moscow), the collapse in commodity prices and some governmental changes have meant that in the 2015-2019 period Latin America is the destination of only 0.8 per cent of Russia's total arms exports. The United States has regained its position as the largest seller to the rest of the continent.

Spain occupies a prominent position in the arms market, as the seventh largest exporter in the world. However, it lags behind in the preferences of Latin American countries, to which it sells less defence materiel than it would be entitled to in terms of the overall volume of trade it maintains with them. Nevertheless, the level of sales increased in 2019, after a year of particularly low figures. In the last five years, Spain has sold 3.6% of its global arms exports to Latin America; in that period, its main customers were Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, Peru and Colombia.

Better military equipment might suggest greater participation in UN peacekeeping missions, perhaps as a way of keeping an army active in a context of a lack of regional deployments. However, of the total of 82,480 troops in the fourteen UN peacekeeping missions at the beginning of 2020, 2,473 came from Latin American countries, which represents only 3 per cent of the total contingent. Moreover, almost half of staff was contributed by one country, Uruguay (45.5% of regional troops). Another small country, El Salvador (12%), is the next most committed to missions, while large countries are under-represented, notably Mexico.

In terms of public safety, 2019 brought the good news of a reduction in homicides in Brazil, which fell by 19.2% compared to the previous year, in contrast to what happened in Mexico, where they rose by 2.5%. If in his first year as president, Jair Bolsonaro scored an important achievement, thanks to the management of the super security minister Sérgio Moro (a success tarnished by the increase in accidental deaths in police operations), in his first year Andrés Manuel López Obrador failed to fulfil one of his main electoral promises and was unable to break the upward trend in homicides that has invariably occurred annually throughout the terms of office of his two predecessors.

In terms of the fight against drug trafficking, 2019 saw two particularly positive developments. On the one hand, coca crops were eradicated for the first time in the VRAEM, Peru's largest production area. Given its difficult accessibility and the presence of Shining Path strongholds, the area had previously been excluded from the operations of subject. On the other hand, the change of presidency in Bolivia meant, according to the US, a greater commitment by the new authorities to combat illicit coca cultivation and interdict drug shipments coming from Peru. In recent years Bolivia has become the major cocaine distributor in the southern half of South America, connecting Peruvian and Bolivian production with the markets of Argentina and especially Brazil, and with its export ports to Europe.

![Venezuelans leaving the country to seek a livelihood in a host country [UNHCR UNHCR]. Venezuelans leaving the country to seek a livelihood in a host country [UNHCR UNHCR].](/documents/10174/16849987/informe-precovid-blog.jpg)

Venezuelans leaving the country to look for a livelihood in a place of refuge [UNHCR UNHCR].

report SRA 2020 / presentation

The Covid-19 pandemic has radically altered security assumptions around the world. The emergence of the coronavirus moved from China to Europe, then to the United States and then to the rest of the Western Hemisphere. Already economically handicapped by its dependence on commodity exports since the beginning of the Chinese slowdown, Latin America suffered from the successive restrictions in the different geographical areas, and finally also entered a crisis of production and consumption and a health and labour catastrophe. The region is expected to be one of the hardest hit, with effects also in the field of security.

This annual report , however, focuses on American regional security in 2019. Although in some respects it includes events from the beginning of 2020, and therefore some early effects of the pandemic, the impact of the pandemic on issues such as regional geopolitics, state budgetary difficulties, organised crime and citizen security can be found at report next year.

To the extent that other security developments in 2019 have been somewhat transitory in recent months, Venezuela has remained the main focus of regional insecurity over the past year. At report we analyse Iran's return to the Caribbean country, after first China and then Russia preferred not to see their own economic interests harmed; we also note the consolidation of the ELN and part of the ex-FARC as binational Colombian-Venezuelan groups.

In addition, we highlight the progress made in the first time that Hezbollah has been designated by several countries as a terrorist organisation, group , and we provide figures on the drop in Russian arms sales to Latin America and the relative lack of marketing in the region of the defence material produced by Spain. We also quantify the contribution of Latin American troops to UN peacekeeping missions, as well as Bolsonaro's success and AMLO's failure in the evolution of homicides in Brazil and Mexico. In terms of drug trafficking, 2019 saw the first coca crop eradication operation in the VRAEM, the most complicated area of Peru in the fight against drugs.

![Revolutionary Guard Commando Naval Exercises in the Strait of Hormuz in 2015 [Wikipedia]. Revolutionary Guard Commando Naval Exercises in the Strait of Hormuz in 2015 [Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/iran-nueva-guerra-fria-blog.jpg)

▲ Revolutionary Guard Commando Naval Exercises in the Strait of Hormuz in 2015 [Wikipedia].

essay / Ana Salas Cuevas

The Islamic Republic of Iran, also known as Persia, is a country of great geopolitical importance. It is a regional power not only because of its strategic location, but also because of its vast hydrocarbon resources, which make Iran the fourth largest country in terms of proven oil reserves and the first in terms of gas reserves[1].

We are talking about one of the most important countries in the world for three main reasons. The first, mentioned above, is its immense oil and gas reserves. entrance Secondly, because Iran controls the Strait of Hormuz, which is the key to the Persian Gulf and through which most of the hydrocarbon exports of Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain pass[2]. 2] And lastly, because of the nuclear programme in which it has invested so many years.

The Iranian republic is based on the principles of Shia Islam, although there is great ethnic diversity in its society. It is therefore essential to take into account the great "strength of Iranian nationalism" in order to understand its politics. By appealing to its dominant position over other countries, the Iranian nationalist movement aims to influence public opinion. Nationalism has been building for more than 120 years, since the Tobacco Boycott of 1891[4] was a direct response to outside intervention and pressure, and today aims to achieve hegemony in the region. Iran's foreign and domestic policies are a clear expression of this movement[5].

Proxy armies (proxy armies)

War by proxy is a war model in which a country uses third parties to fight or influence a given territory, rather than engaging directly. As David Daoud points out, in Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen and Syria, 'Tehran has perfected the art of gradually conquering a country without replacing its flag'[6]. The Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard (IRGC) is directly involved in this task, militarily training or favouring the forces of other countries.

The GRI was born with the Islamic Revolution led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, in order to maintain the achievements of the movement[7]. 7] It is one of the main political and social actors in the country. It has a great capacity to influence national political debates and decisions. It is also the owner of numerous companies in the country, which guarantees it its own funding source and reinforces its character as an internal power. It is an independent body from the armed forces, and the appointment of its senior officers depends directly on the Leader of the Revolution. Among its objectives is the fight against imperialism, and it expressly commits itself to trying to rescue Jerusalem and return it to the Palestinians[8]. 8] Their importance is crucial to the regime, and any attack on these bodies represents a direct threat to the Iranian government.

Iran's relationship with the Muslim countries around it is marked by two main facts: on the one hand, its Shiite status; on the other, the pre-eminence it has achieved in the past in the region[10]. 10] Thanks to the fact that its external action is supported by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard, Iran has managed to establish strong links with political and religious groups throughout the Middle East. From there, Iran uses a variety of means to strengthen its influence in different countries. Firstly, by using soft power tools. Thus, among other actions, Iran has participated in the reconstruction of mosques and schools in countries such as Lebanon and Iraq[11]. 11] In Yemen, it has provided logistical and economic aid to the Houthi movement. In 2006, it was involved in the reconstruction of South Beirut.

However, the methods used by these forces go to other extremes, moving towards more intrusive(hard power) mechanisms. For example, following the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Iran has established a foothold there over three decades, with Hezbollah as a proxy, taking advantage of complaints about the disenfranchisement of the Shia community. This course of action has allowed Tehran to promote its Islamic Revolution abroad[12].

In Iraq, the GRI sought to destabilise Iraq internally by supporting Shiite factions such as the Badr organisation during the Iranian-Iraqi war of the 1980s. Iran, on the other hand, involved the GRI in Saddam Hussein's uprising in the early 1990s. Through this subject of influences and embodying the proxy army paradigm, Iran has been establishing very direct influence over these places. Even in Syria, this elite Iranian corps is highly influential, supporting the Assad government and the Shia militias fighting alongside it.

For its part, Saudi Arabia accuses Iran and its Guard of supplying arms in Yemen to the Houthis (a movement that defends the Shiite minority), generating a major escalation of tension between the two countries.

The GRI has thus established itself as one of the most important factors in the Middle East landscape, driving the struggle between two opposing camps. However, it is not the only one. In this way, we find a "cold war" scenario, which ends up transcending and becoming an international focus. On the one hand, Iran, supported by powers such as Russia and China. On the other, Saudi Arabia, supported by the US. This conflict is developing, to a large extent, in an unconventional manner, through proxy armies such as Hezbollah and the Shiite militias in Iraq, Syria and Yemen[14].

Causes of confrontation

Tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran have spread throughout the Middle East (and beyond), creating two distinct camps in the Middle East, both seeking to claim hegemony in the region.

To interpret this scenario and better understand civil service examination it is important, first of all, to distinguish between two opposing ideological currents: Shiism and Sunnism (Wahhabism). Wahhabism is an extreme right-wing Muslim religious tendency of the Sunni branch, which is today the majority religion in Saudi Arabia. Shi'ism, as previously mentioned, is the current on which the Republic of Iran is based. However, as we shall see, the struggle between Iran and Saudi Arabia is political, not religious; it is based more on ambition for power than on religion.

Secondly, the control of oil trafficking is another cause of this rivalry. To understand this reason, it is worth bearing in mind the strategic position that the countries of the Middle East play on the global map, as they are home to the world's largest hydrocarbon reserves. issue A large number of contemporary struggles are in fact due to the interference of the major powers in the region, seeking to play a role in these territories. Thus, for example, the 1916 Sykes-Picot[15] agreement for the distribution of European influences continues to condition current events. Both Saudi Arabia and Iran, as we have said, have a special role to play in these confrontations, for the reasons described above.

Under these considerations, it is important to note, thirdly, the involvement in these tensions of external powers such as the United States.

The effects of the Arab Spring have weakened many countries in the region. Not so Saudi Arabia and Iran, which in recent decades have sought to consolidate their position as regional powers, largely thanks to the support provided by their oil production and large oil reserves. The differences between the two countries are reflected in the way they seek to shape the region and the different interests they pursue. In addition to the ethnic differences between Iran (Persians) and Saudi Arabia (Arabs), their alignment on the international stage is also opposite. Wahhabism presents itself as anti-American, but the Saudi government is aware of its need for US support, and the two countries have a reciprocal convenience, with oil as a basis. The same is not true of Iran.

Iran and the US were close allies until 1979. The Islamic Revolution changed everything and since then, with the hostage crisis at the US embassy in Tehran as a particularly dramatic initial moment, tensions between the two countries have been frequent. The diplomatic confrontation has become acute again with President Donald Trump's decision to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed in 2015 for Iran's nuclear non-proliferation, with the consequent resumption of economic sanctions against Iran. Moreover, in April 2019, the United States placed the Revolutionary Guard on its list of terrorist organisations[16], holding Iran responsible for financing and promote terrorism as a government tool [17].

On the one side, then, are the Saudis, supported by the US and, within the region, by the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Bahrain and Israel. On the other side are Iran and its allies in Palestine, Lebanon (pro-Shiite side) and recently Qatar, to which Syria and Iraq (Shiite militias) could be added. Tensions increased after the death of Qasem Soleimani in January 2020. In the latter camp we could highlight the international support of China and Russia, but little by little we can observe a distancing of relations between Iran and Russia.

When talking about the struggle for hegemony in the control of oil trafficking, it is essential to mention the Strait of Hormuz, the crucial geographical point of this conflict, where both powers are directly confronted. This strait is a strategic area located between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. Forty percent of the world's oil passes through it[18]. Control of these waters is obviously decisive in the confrontation between Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as for any of the members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries of the Middle East (OPEC) in the region: Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait.

One of the objectives of Washington's economic sanctions against Iran is to reduce its exports in order to favour Saudi Arabia, its largest regional ally. To this end, the US Fifth Fleet, based in Bahrain, is tasked with protecting commercial shipping at area.

The Strait of Hormuz "is the escape valve Iran uses to relieve pressure from outside the Gulf" [19]. From here, Iran tries to react to economic sanctions imposed by the US and other powers; it is this that gives it a greater voice on the international stage, as it has the ability to block the strategic passage. Recently there have been attacks on oil tankers from Saudi Arabia and other countries[20], which causes great economic and military destabilisation with each new episode[21].

At final, the skill between Iran and Saudi Arabia has an effect not only regionally but also globally. The conflicts that could erupt in this area are increasingly reminiscent of a familiar Cold War, both in terms of the methods on the battlefront (and the incidence of proxy armies on this front), and the attention it requires for the rest of the world, which depends on this result, perhaps more than it is aware of.

Conclusions

For several years now, a regional confrontation has been building up that also involves the major powers. This struggle transcends the borders of the Middle East, similar to the status unleashed during the Cold War. Its main actors are the proxy armies, which are driving struggles through non-state actors and unconventional methods of warfare, constantly destabilising relations between states, as well as within states themselves.

To avoid the fighting in Hormuz, countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have tried to transport oil in other ways, for example by building pipelines. This tap is held by Syria, through which the pipelines must pass in order to reach Europe). In the end, the Syrian war can be seen from many perspectives, but there is no doubt that one of the reasons for the meddling of extra-regional powers is the economic interest in the Syrian coastline.

From 2015 to the present, Yemen's civil war has been raging in silence. At stake are strategic issues such as control of the Mandeb Strait. Behind this terrible war against the Houthis(proxies), there is a latent fear that the Houthis will take control of access to the Red Sea. In this sea and close to the strait is Djibouti, where the major powers have installed instructions to better control the area.

The most affected power is Iran, which sees its Economics weakened by constant economic sanctions. The status affects a population oppressed both by its own government and by international pressure. The government itself ends up misinforming society, leading to a great mistrust of the authorities. This leads to growing political instability, which manifests itself in frequent protests.

The regime has publicised these demonstrations as protests against US actions, such as the assassination of General Soleimani, without mentioning that many of these revolts are due to widespread civilian discontent over the serious measures taken by Ayatollah Khamenei, who is more focused on pursuing hegemony in the region than on resolving internal problems.

Thus, it is often difficult for the majority of the world to realise the implications of these confrontations. Indeed, the use of proxy armies should not distract us from the fact of the real involvement of major powers in the West and East (in true Cold War fashion). Nor should the alleged motives for keeping these fronts open distract us from the true incidence of what is really at stake: none other than the global Economics .

[1] El nuevo mapa de los gigantes globales del petróleo y el gas, David Page, Expansión.com, 26 June 2013. available en

[2] The four points core topic through which oil travels: The Strait of Hormuz, Iran's "weapon", 30 July 2018. available en

[3] In November 2013, China, Russia, France, the United Kingdom and the United States (P5) and Iran signed the Joint Plan of Action (JPOA). This was an initial agreement on Iran's nuclear programme, which was the subject of several negotiations leading to a final pact, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed in 2015, to which the European Union adhered.

[4] The Tobacco Boycott was the first movement against a concrete action of the state; it was not a revolution in the strict sense of the word, but a strong nationalism was rooted in it. It came about because of the tobacco monopoly law granted to the British in 1890. More information in: "El veto al tabaco", Joaquín Rodríguez Vargas, Professor at the Complutense University of Madrid.

[5] notebook de estrategia 137, Ministerio de Defensa: Iran, potencia emergente en Oriente Medio. Implications for Mediterranean stability. high school Español de programs of study Estratégicos, July 2007. available en

[6] Meet the Proxies: How Iran Spreads Its Empire through Terrorist Militias,The Tower Magazine, March 2015. available en

[7] article 150 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran expressly states this.

[8] Tensions between Iran and the United States: causes and strategies, Kamran Vahed, high school Spanish Strategic programs of study , November 2019. available en, p. 5.

[9] One of the six sections of the GRI is the "Quds" Force (commanded by Qasem Soleimani), which specialises in conventional warfare and military intelligence operations. It also manager to conduct extraterritorial interventions.

[11] Iran-US tensions: causes and strategies, Kamran Vahed, high school Spanish Strategic programs of study , November 2019. available en

[13] Yemen: the battle between Saudi Arabia and Iran for influence in the region, Kim Amor, 2019, El Periódico. available en

[14] Iran versus Saudi Arabia, an imminent war?, Juan José Sánchez Arreseigor, IEEE, 2016. available en

[15] The Sykes-Picot agreement was a secret pact between Britain and France during World War I (1916) in which, with the consent of (pre-Soviet) Russia, the two powers divided up the conquered areas of the Ottoman Empire after the Great War.

[17] Statement from the President on the Designation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, Foreign Policy, April 2019. available en

[18] The Strait of Hormuz, the world's main oil artery, Euronews (data checked with Vortexa), 14 June 2019. available en

![Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia]. Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-isi-blog.jpg)

Logo of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organization. It depicts Pakistan's national animal, Markhor, eating a snake [Wikipedia].

ESSAY / Manuel Lamela

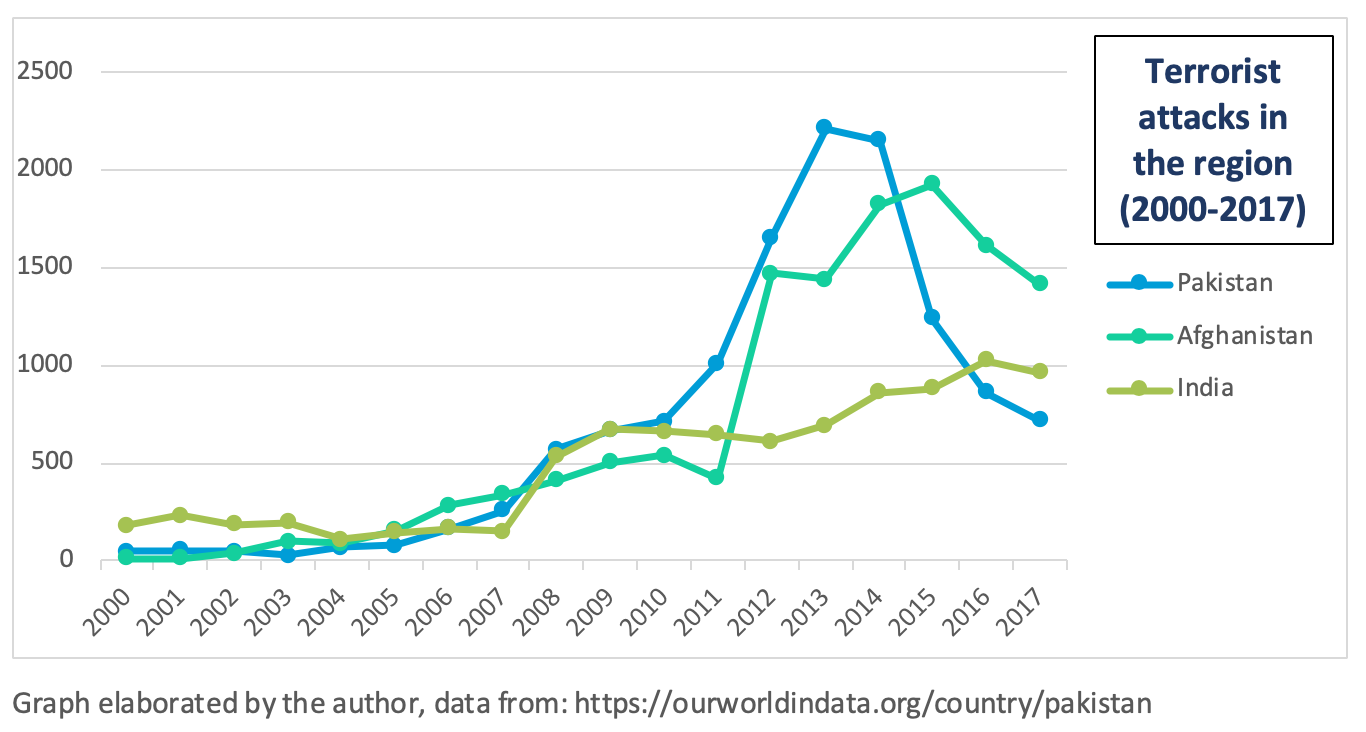

Jihadism continues to be one of the main threats Pakistan faces. Its impact on Pakistani society at the political, economic and social levels is evident, it continues to be the source of greatest uncertainty, which acts as a barrier to any company that is interested in investing in the Asian country. Although the situation concerning terrorist attacks on national soil has improved, jihadism is an endemic problem in the region and medium-term prospects are not positive. The atmosphere of extreme volatility and insistence that is breathed does not help in generating confidence. If we add to this the general idea that Pakistan's institutions are not very strong due to their close links with certain radical groups, the result is a not very optimistic scenario. In this essay, we will deal with the current situation of jihadism in Pakistan, offering a multidisciplinary approach that helps to situate itself in the complicated reality that the country is experiencing.

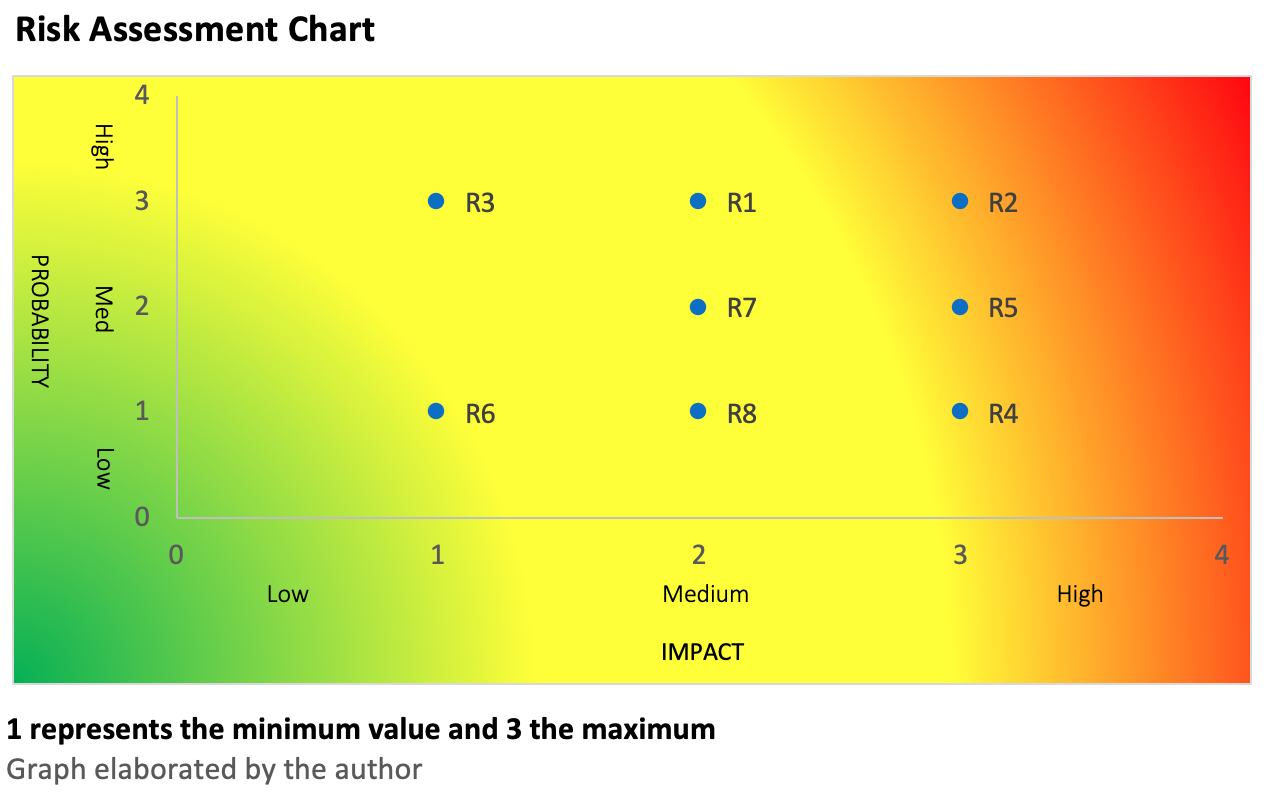

1. Jihadism in the region, a risk assessment

Through this graph, we will analyze the probability and impact of various risk factors concerning jihadist activity in the region. All factors refer to hypothetical situations that may develop in the short or medium term. The increase in jihadist activity in the region will depend on how many of these predictions are fulfilled.

Risk Factors:

A1: US-Taliban treaty fails, creating more instability in the region. If the United States is not able to make a proper exit from Afghanistan, we may find ourselves in a similar situation to that experienced during the 1990s. Such a scenario will once again plunge the region into a fierce civil war between government forces and Taliban groups. The proposed scenario becomes increasingly plausible if we look at the recent American actions regarding foreign policy.

A2: Pakistan two-head strategy facing terrorism collapse. Pakistan's strategy in dealing with jihadism is extremely risky, it's collapse would lead to a schism in the way the Asian state deals with its most immediate challenges. The chances of this strategy failing in the medium term are considerably high due to its structure, which makes it unsustainable over the time.

R3: Violations of the LoC by the two sides in the conflict. Given the frequency with which these events occur, their impact is residual, but it must be taken into account that it in an environment of high tension and other factors, continuous violations of the LoC may be the spark that leads to an increase in terrorist attacks in the region.

R4: Agreement between the afghan Taliban and the government. Despite the recent agreement between Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Albduallah, it seems unlikely that he will be able to reach a lasting settlement with the Taliban, given the latter's pretensions. If it is true that if it happens, the agreement will have a great impact that will even transcend Afghan borders.

R5: Afghan Taliban make a coup d'état to the afghan government. In relation to the previous point, despite the pact between the government and the opposition, it seems likely that instability will continue to exist in the country, so a coup attempt by the Taliban seems more likely than a peaceful solution in the medium or long term

R6: U.S. Democrat party wins the 2020 elections. Broadly speaking, both Republican and Democratic parties are betting on focusing their efforts on containing the growth of their great rival, China.

R7: U.S. withdraw its troops from Afghanistan regarding the result of the peace process. This is closely related to the previous point as it responds to a basic geopolitical issue.

R8: New agreement between India and Pakistan regarding the LoC. If produced, this would bring both states closer together and help reduce jihadist attacks in the Kashmir region. However, if we look at recent events, such a possibility seems distant at present.

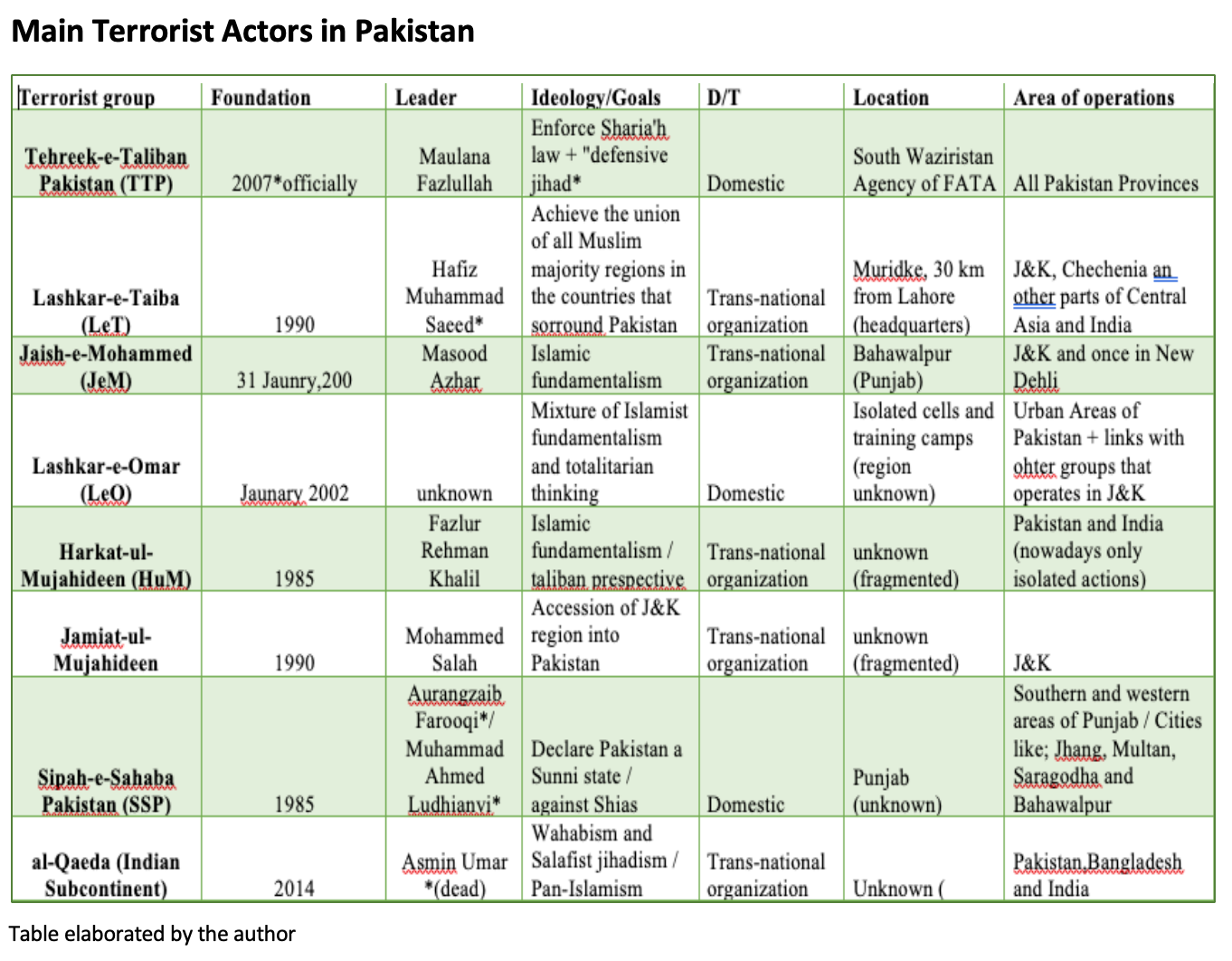

2. The ties between the ISI and the Taliban and other radical groups

Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) has been accused on many occasions of being closely linked to various radical groups; for example, they have recently been involved with the radicalization of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh[1]. Although Islamabad continues strongly denying such accusations, reality shows us that cooperation between the ISI and various terrorist organisations has been fundamental to their proliferation and settlement both on national territory and in the neighbouring states of India and Afghanistan. The West has not been able to fully understand the nature of this relationship and its link to terrorism. The various complaints to the ISI have been loaded with different arguments of different kinds, lacking in unity and coherence. Unlike popular opinion, this analysis will point to the confused and undefined Pakistani nationalism as the main cause of this close relationship.

The Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence, together with the Intelligence Bureau and the Military Intelligence, constitute the intelligence services of the Pakistani State, the most important of which is the ISI. ISI can be described as the intellectual core and center of gravity of the army. Its broad functions are the protection of Pakistan's national security and the promotion and defense of Pakistan's interests abroad. Despite the image created around the ISI, in general terms its activities and functions are based on the same "values" as other intelligence agencies such as the MI6, the CIA, etc. They all operate under the common ideal of protecting national interests, the essential foundation of intelligence centers without which they are worthless. We must rationalize their actions on the ground, move away from inquisitive accusations and try to observe what are the ideals that move the group, their connection with the government of Islamabad and the Pakistani society in general.

2.1. The Afghan Taliban

To understand the idiosyncrasy of the ISI we must go back to the war in Afghanistan[2], it is from this moment that the center begins to build an image of itself, independent of the rest of the armed forces. From the ISI we can see the victory of the Mujahideen on Afghan territory as their own, a great achievement that shapes their thinking and vision. But this understanding does not emerge in isolation and independently, as most Pakistani society views the Afghan Taliban as legitimate warriors and defenders of an honourable cause[3]. The Mujahideen victory over the USSR was a real turning point in Pakistani history, the foundation of modern Pakistani nationalism begins from this point. The year 1989 gave rise to a social catharsis from which the ISI was not excluded.

Along with this ideological component, it is also important to highlight the strategic aspect; we are dealing with a question of nationalism, of defending patriotic interests. Since the emergence of the Taliban, Pakistan has not hesitated to support them for major strategic reasons, as there has always been a fear that an unstable Afghanistan would end up being controlled directly or indirectly by India, an encirclement strategy[4]. Faced with this dangerous scenario, the Taliban are Islamabad's only asset on the ground. It is for this reason, and not only for religious commitment, that this bond is produced, although over time it is strengthened and expanded. Therefore, at first, it is Pakistani nationalism and its foreign interests that are the cause of this situation, it seeks to influence neighbouring Afghanistan to make the situation as beneficial as possible for Pakistan. Later on, when we discuss the situation of the Taliban on the national territory, we will address the issue of Pakistani nationalism and how its weak construction causes great problems for the state itself. But on Afghan territory, from what has been explained above, we can conclude that this relationship will continue shortly, it does not seem likely that this will change unless there are great changes of impossible prediction. The ISI will continue to have a significant influence on these groups and will continue its covert operations to promote and defend the Taliban, although it should be noted that the peace treaty between the Taliban and the US[5] is an important factor to take into account, this issue will be developed once the situation of the Taliban at the internal level is explained.

2.2. The Pakistani Taliban (Al-Qaeda[6] and the TTP)

The Taliban groups operating in Pakistan are an extension of those operating in neighbouring Afghanistan. They belong to the same terrorist network and seek similar objectives, differentiated only by the place of action. Despite this obvious similarity, from Islamabad and increasingly from the whole of Pakistani society, the two groups are observed in a completely different way. On the one hand, as we said earlier, for most Pakistanis, the Afghan Taliban are fighting a legitimate and just war, that of liberating the region from foreign rule. However, groups operating in Pakistan are considered enemies of the state and the people. Although there was some support among the popular classes, especially in the Pashtun regions, this support has gradually been lost due to the multitude of atrocities against the civilian population that have recently been committed. The attack carried out by the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)[7] in the Army Public School in Peshawar in the year 2014 generated a great stir in society, turning it against these radical groups. This duality marks Pakistan's strategy in dealing with terrorism both globally and internationally. While acting as an accomplice and protector of these groups in Afghanistan, he pursues his counterparts on their territory. We have to say that the operations carried out by the armed forces have been effective, especially the Zarb-e-Azb operation carried out in 2014 in North Waziristan, where the ISI played a fundamental role in identifying and classifying the different objectives. The position of the TTP in the region has been decimated, leaving it quite weakened. As can be seen in this scenario, there is no support at the institutional level from the ISI[8], as they are involved in the fight against these radical organisations. However, on an individual level if these informal links appear. This informal network is favoured by the tribal character of Pakistani society, it can appear in different forms but often draw on ties of Kinship, friendship or social obligation[9]. Due to the nature of this type of relationship, it is impossible to know to what extent the ISI's activity is conditioned and how many of its members are linked to Taliban groups. However, we would like to point out that these unions are informal and individual and not institutional, which provides a certain degree of security and control, at least for the time being, the situation may vary greatly due to the lack of transparency.

2.3. ISI and the radical groups that operate in Kashmir

Another part of the board is made up of the radical groups that focus their terrorist attention on the conflict with India over control of Kashmir, the most important of which are: Lashkar-e-Taiba (Let) and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM). Both groups have committed real atrocities over the past decades, the most notorious being the one committed by LeT in the Indian city of Mumbai in 2008. There are numerous testimonies, in particular, that of the American citizen David Haedy, which point to the cooperation of the ISI in carrying out the aforementioned attack.[10]