Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Security and defence .

![Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons]. Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons].](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-punjab-blog.jpg)

▲ Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, also called Kartarpur Sahib, is a Sikh holy place in Kartarpur, in the Pakistani Punjab [Wikimedia Commons].

ESSAY / Pablo Viana

Punjab region has been part of India until the year 1947, when the Punjab province of British India was divided in two parts, East Punjab (India) and West Punjab (Pakistan) due to religious reasons. After the division a lot of internal violence occurred, and many people were displaced.

East and West Punjab

The partition of Punjab proved to be one of the most violent, brutal, savage debasements in the history of humankind. The undivided Punjab, of which West Punjab forms a major region today, was home to a large minority population of Punjabi Sikhs and Hindus unto 1947 apart from the Muslim majority[1]. This minority population of Punjabi Sikhs called for the creation of a new state in the 1970s, with the name of Khalistan, but it was detained by India, sending troops to stop the militants. Terrorist attacks against the Sikh majority emerged, by those who did not accept the creation of the state of Khalistan and wished to stay in India.

The Sikh population is the dominant religious ethnicity in East Punjab (58%) followed by the Hindu (39%). Sikhism and Islamism are both monotheistic religions, they do believe on the same concept of God, although it is different on each religion. Sikhism was developed during the 16th and 17th century in the context of conflict in between Hinduism and Islamism. It is important to mention Sikhism if we talk about Punjab, as its origins were in Punjab, but most important in recent times, is that the Guru Nanak Dev[2] was buried in Pakistani territory. Four kilometres from the international border the Sikh shrine was conceded to Pakistan at the time of British India's Partition in 1947. For followers of Sikhism this new border that cut through Punjab proved especially problematic. Sikhs overwhelmingly chose India over the newly formed Pakistan as the state that would best protect their interests (there are an estimated 50,000 Sikhs living in Pakistan today, compared to the 24 million in India). However, in making this choice, Sikhs became isolated from several holy sites, creating a religious disconnection that has proved a constant spiritual and emotional dilemma for the community[3].

In order to let the Sikhist population visit the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib[4], the Kartarpur Corridor was created in November 2019. However, there is an incessant suspicion in between India and Pakistan that question Pakistan motives. Although it seems like a generous move work of the Pakistani government, there is a clear perception that Pakistan is engaged in an act of deception[5]. Thus, although this scenario might seem at first beneficial for the rapprochement of East and West Punjab, it is not at all. Pakistan is involved in a rhetorical policy which could end up worsening its relations with India.

The division of Punjab in 1947 was like the division of Pakistan and India on that same year. Territorial disputes have been an issue that defines very well India-Pakistan relations since the independence. In the case of Punjab, there has not been a territorial discussion. The division was clear and has been respected ever since. Why would Pakistan and/or India be willing to unify Punjab? There is no reason. East and West Punjab represent two different nations and three religions. If we think about reunifying Pakistan and India, the conclusion is the same (although more dramatic); too many discrepancies and recent unrest to think about bringing back together the nations. However, if the Kartarpur Corridor could be placed out of bonds for the territorial disputes between Pakistan and India (e.g. Kashmir), Islamabad and New Delhi could use this situation as a model to find out which are the pressure points and trying to find a path for identifying common solutions. In order to achieve this, there should be a clear behaviour by both parties of cooperation. Sadly, in recent times both Pakistan and India have discrepancies regarding many topics and suspicious behaviours that clearly show that they won't be interested in complicating more the situation in Punjab searching for unification. The riots of 1947 left a terrific era on the region and now that both sides are established and no major disputes have emerged (except for Sikh nationalism), the situation should and will most likely remain as it is.

The Indus Water Treaty

The Indus Waters Treaty was signed in 1960 after nine years of negotiations between India and Pakistan with the help of the World Bank, which is also a signatory. Seen as one of the most successful international treaties, it has survived frequent tensions, including conflict, and has provided a framework for irrigation and hydropower development for more than half a century. The Treaty basically provides a mechanism for exchange of information and cooperation between Pakistan and India regarding the use of their rivers. This mechanism is well known as the Permanent Indus Commission. The Treaty also sets forth distinct procedures to handle issues which may arise: "questions" are handled by the Commission; "differences" are to be resolved by a Neutral Expert; and "disputes" are to be referred to a seven-member arbitral tribunal called the "Court of Arbitration." As a signatory to the Treaty, the World Bank's role is limited and procedural[6].

Since 1948, India has been confident on the fact that East Punjab and the acceding states have a prior and superior claim to the rivers flowing through their territory. This leaves West Punjab in disadvantage regarding water resources, as East Punjab can access the highest sections of the rivers. Even under a unified control designed to ensure equitable distribution of water, in years of low river flow cultivators on tail distributaries always tended to accuse those on the upper reaches of taking an undue amount of the water, and after partition any temporary shortage, whatever the cause, could easily be attributed to political motives. It was therefore wise of Pakistan-indeed it became imperative-to cut the new feeder from the Ravi for this area and thus become independent of distributaries in East Punjab[7]. The Treaty acknowledges the control of the eastern rivers to India, and to the western rivers to Pakistan.

The main issue of water distribution in between East and West Punjab is then a matter of geography. Even though West Punjab covers more territory than East Punjab, and the water flow of West Punjab is almost three times the water flow of East Punjab rivers, the Indus Water Treaty gives the following advantage to India: since Pakistan rivers receive much more water flow from India, the treaty allowed India to use western rivers water for limited irrigation use and unlimited use for power generation, domestic, industrial and non-consumptive uses such as navigation, floating of property, fish culture and this is where the disputes mainly came from, as Pakistan has objected all Indian hydro-electric projects on western rivers irrespective of size and layout.

It is worth mentioning that with the World Bank mediating the Treaty in between India and Pakistan, the water access will not be curtailed, and since the ratification of the Treaty, India and Pakistan have not engaged in any water wars. Although there have been many tensions the disputes have been via legal procedures, but they haven't caused any major cause for conflict. Today, both countries are strengthening their relationship, and the scenario is not likely to get worse, it is actually the opposite, and the Indus Water Treaty is one of the few livelihoods of the relationship. If the tensions do not cease, the World Bank should consider the possibility of amending the treaty, obviously if both Pakistan and India are willing to cooperate, although with the current environment, a renegotiation of the treaty would probably bring more complications. There is no shred of evidence that India has violated the Indus Water Treaty or that it is stealing Pakistan's water[8], although Pakistan does blame India for breaching the treaty, as shown before. This is pointed out by Hindu politicians as an attempt by Pakistan to divert the attention of its own public from the real issues of gross mismanagement of water resources[9].

Pakistan has a more hostile attitude regarding water distribution, trying to find a way to impeach India, meanwhile India focuses on the development of hydro-electric projects. India won't stop providing water to the West Punjab, as the treaty is still in force and is fulfilled by both parties. Pakistan should reconsider its role and its benefits received thanks to the treaty and meditate about the constant pressure towards India, as pushing over the limit could mean a more hostile activity carried out by India, which in the worst case scenario (although not likely to happen) could mean a breakdown of the treaty.

[1] The Punjab in 1920s - A Case study of Muslims, Zarina Salamat, Royal Book Company, Karachi, 1997. table 45, pp. 136.

[2] Guru Nanak Dev was the founder of Sikhism (1469-1540)

[3] Wyeth, G. (Dec 28, 2019). Opening the Gates: The Kartarpur Corridor. Australian Institute of International Affairs.

[4] Site where Guru Nanak Dev settled the Sikh community, and lived for 18 years after his death in 1539.

[5] Islamabad promoted the activity of Sikhs For Justice including the will to establish the state of Khalistan.

[6] World Bank (June 11, 2018). Fact Sheet: The Indus Waters Treaty 1960 and the Role of the World Bank.

[7] F.J. Fowler (Oct 1950) Some Problems of Water Distribution between East and West Punjab p. 583-599.

[8] S. Chandrasekharan (Dec 11, 2017) Indus Water Treaty: Review is not an Option South Asia Analysis Group.

[9] Mohan, G. (Feb 3, 2020). India rejects Pakistan average report on Indus water sharing India Today.

![Attack in Kashmir linked to groups of Pakistani origin [tweeted by @ANI]. Attack in Kashmir linked to groups of Pakistani origin [tweeted by @ANI].](/documents/10174/16849987/pakistan-yihadismo-blog.jpg)

▲ Attack in Kashmir linked to groups of Pakistani origin [twitted by @ANI].

ESSAY / Isabel Calderas [Ignacio Lucas as research assistant].

There is a myriad of security concerns regarding external factors when it comes to Pakistan: India, Afghanistan, the Saudi Arabia-Iran split and the United States, to name a few. However, there are also two main concerns that come from within: jihadism and organised crime. They are interconnected but differ in many ways. The latter is frequently overlooked to focus on the former, but both have the capacity of affecting the country, internally and externally, as the effectiveness of dealing with them impacts the perception the international community has of Pakistan. While internally disrupting, these problems also have international reach, as such groups often export their activities, adversely affecting at a global scale. Therefore, international actors put so much pressure on Pakistan to control them. Historically, there has been much scepticism over the government's ability, or even willingness to solve these risks. We will examine both problems separately, identifying the impact they have on the national and international arena, as well as the government's approach to dealing with either and the future risks they entail.

1. JIHADISM

Pakistan's education system has become a central part of the country's radicalization phenomenon[1], in the materialization of madrassas. These schools, which teach a more puritanical version of Islam than had traditionally been practiced in Pakistan, have been directly linked to the rise of jihadist groups[2]. Saudi Arabia, who has always had very close relations with Pakistan, played a key role in their development, by funding the Ahl-e-Hadith and Deobandi madrassas since the 1970s. The Iranian revolution bolstered the Saudi's imperative to control Sunnism in Pakistan, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan gave them the vehicle to do so[3]. In these schools, which teach a biased view of the world, students display low tolerance for minorities and are more likely to turn to jihadism.

Saudi and American funding of madrassas during the Soviet occupation helped the Pakistani army's intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), become more powerful, as they channelled millions of dollars to them, a lot of which went into the madrassas which sent mujahedeen fighters to fight for their cause[4]. The Taliban's origins can also be traced to these, as the militia was raised mainly from Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan and Saudi-funded madrassas[5].

Madrassas are especially popular in the poorer provinces of the country, where parents send their children to them for several non-religious reasons. First, because the Qur'an is written in Arabic and madrassas teach this language[6]. The dire situation of many families forces millions of Pakistanis to migrate to neighbouring, oil-rich Arabic-speaking countries, from where they send remittances home to help support their families. Secondly, the public-school system in Pakistan is weak, often failing to teach basic reading skills[7], something the madrassas do teach.

Partly in response to the international pressure[8] it has been under to fight terrorism within its territory; Pakistan has tried to reform the madrassas. The government has stated its intention to bring madrassas under the umbrella of the education ministry, financing these schools by allocating cash otherwise destined to fund anti-terrorism security operations[9]. It plans to add subjects like science to the curriculum, to lessen the focus on Islamic teachings. However, this faces several challenges, among which the resistance from the teachers and clerical authorities who run the madrassas outstands[10].

Before moving on to the prominent radical groups in Pakistan, we would like to make a brief summary on a different cause of radicalization: the unintended effect of the drone strategy adopted by the United States.

The United States has increasingly chosen to target its radical enemies in Pakistan through the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), which can be highly effective in neutralizing objectives, but also pose a series of risks, like the killing of innocent civilians that are in the neighbouring area. This American strategy, which Pakistan has publicly criticized, has fomented anti-American sentiment among the Pakistanis, at a ratio on average of every person killed resulting in the radicalization of several more people[11]. The growing unpopularity of drone strikes has further weakened relations between both governments, but shows no signs of changing in the future, if recent attacks carried by the U.S. are any indication. Pakistan's efforts to de-radicalize its population will continue to be undermined by the U.S. drone strikes[12].

Pakistan's anti-terrorism strategy is linked to its geostrategic and regional interests, especially dealing with its eastern and western neighbours[13]. There are many radical groups operating within their territory, and the government's strategy towards them shifts depending on their goal[14]. Groups like the Afghan Taliban, who target foreign invasions in their own country, and Al Qaeda, whose jihad against the West is on a global scale, have been allowed to use Pakistani territory to coordinate operations and take refuge. Their strategy is quite different for Pakistani Taliban group, Tehrik-e-Taliban (TTP) who, despite being allied with the Afghan Taliban, has a different goal: to oust the Pakistani government and impose Sharia law[15]. Most of the military's campaigns aimed at cracking down on radicals have been targeted at weakening groups affiliated with TTP. Lastly, there are those groups with whom some branches of the Pakistani government directly collaborate with.

Pakistan has been known to use jihadi organisations to advance its security objectives through proxy conflicts. Pakistan's policy of waging war through terrorist groups is planned, coordinated, and conducted by the Pakistani Army, specifically the ISI[16] who, as previously mentioned, plays a vital role in running the State.

Although this has been a longstanding cause of tension between the Pakistani and the American governments, the U.S. has made no progress in persuading or compelling the Pakistani military to sever ties with the radical groups[17], even though the Pakistani government has stated that it has, over the past year, 'fought and eradicated the menace of terrorism from its soil' by carrying out arrests, seizing property and freezing bank accounts of groups proscribed by the United States and the United Nations[18]. Their actions have been enough to keep them off the FATF's blacklist for financing terrorism and money laundering[19], which would prevent them from getting financing, but concerns remain about ISI's involvement with radical groups, the future of the relations between them, the overall activity of these groups from within Pakistani territory, and the risk of a future attack to its neighbours.

We will use two of Pakistan's main proxy groups, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad, to analyse the feasibility of an attack in the near future.

1.1. Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT)

Created to support the resistance against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, LeT now focuses on the insurgencies in Afghanistan and Kashmir, the highest priorities for the Pakistani military's foreign policy. The Ahl-e-Hadith group is led by its founder, Hafiz Saeed. Its headquarters are in Punjab. Unlike its counterparts, it is a well-organized, unified, and hierarchical organization, which has become highly institutionalized in the last thirty years. As a result, it has not suffered any major losses or any fractures since its inception[20].

Since the Mumbai attacks in 2008 (which also involved ISI), for which LeT were responsible, its close relationship with the military has defined the group's operations, most noticeably by restraining their actions in India, which reflects both the Pakistani military's desire to avoid international pressure and conflict with their neighbour and the group's capability to contain its members. The group has calibrated its activities, although it possesses the capability to expand its violence. Its outlets for violence have been Afghanistan and Kashmir, which align with the Pakistani military's diary: to bring Afghanistan under Pakistan's sphere of influence while keeping India off-balance in Kashmir[21]. The recent U.S.-Taliban deal in Afghanistan and militarization of Kashmir by India may change this. LeT has benefited handsomely for its loyalty, receiving unparalleled protection, patronage, and privilege from the military. However, after twelve years of restraint, Lashkar undoubtedly faces pressures from within its ranks to strike against India again, especially now that Narendra Modi is prime minister.

1.2. Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM)

The Deobandi organisation, led by its founder Masood Azhar, has had close bonds with Al-Qaeda and the Taliban since they came into light in 2000. With the commencement of the war on terror in Afghanistan, JeM reciprocated by launching an attack on the Indian Parliament on December 2001, in cooperation with LeT. However, it ignored the Pakistani military's will in 2019 when it launched the Pulwama attack, after which the government of Pakistan launched a countrywide crackdown on them, taking leaders and members into preventive custody[22].

1.3. Risk assessment

Although it has gone rogue before, Jaish-e-Muhammad has been weakened by the recent government's crackdown. What remains of the group, consolidated under Masood Azhar, has repaired ties with the military. Although JeM has demonstrated it still possesses formidable capability in Indian Kashmir, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba represents the main concern for an attack on India in the near future.

Lashkar has been both the most reliable and loyal of all the proxy groups and has also proven it does not take major action without prior approval from the ISI, which could become a problem. Pakistan has adopted a policy of maintaining plausible deniability for any attacks in order to avoid international pressure after 9/11, thus LeT's close ties with the military make it more likely that its actions will provoke a war between the two countries.

The United States has tried for several years to get Pakistan to stop using proxies. There are several scenarios in which Lashkar would break from the Pakistani state (or vice versa), but they are farfetched and beyond foreign influence: a) a change in Pakistan's security calculus, b) a resolution on Kashmir, c) a shift in Lashkar's responsiveness and d) a major Lashkar attack in the West[23].

a) A change in Pakistan's security calculus is the least likely, as the India-centric understanding of Pakistan's interests and circumstances is deeply embedded in the psyche of the security establishment[24].

b) A resolution on Kashmir would trouble Lashkar, who seeks full unification of all Kashmir with Pakistan, which would not be the outcome of a negotiated resolution. More so, Modi's recent decision regarding article 370 puts this possibility even further into the future.

c) A shift in Lashkar responsiveness would be caused by the internal pressures to perform another attack, after more than a decade of abiding by the security establishment's will. If perceived as too powerful of insufficiently responsive, ISI would most likely seek to dismantle the group, as they did with Jaish-e-Muhammad, by focusing on the rogue elements and leaving Lashkar smaller but more responsive. This presents a threat, as the group would not allow itself to be simply dismantled but would probably resist to the point of becoming hostile[25].

d) The last option, a major Lashkar attack in the West, is also unlikely, as the group has not undertaken any major attack without perceived greenlight from ISI.

This does not mean that an attack from LeT can be ruled out. ISI could allow the group to carry out an attack if, in the absence of a better reason, it feels that the pressure from within the group will start causing dissent and fractures, just like it happened in 2008. It is in ISI's best interest that Lashkar remains a strong, united ally. Knowing this, it is important to note that a large-scale attack in India by Lashkar is arguably the most likely trigger to a full-blown conflict between the two nations. Even a smaller-scale attack has the potential of provoking India, especially under Modi.

If such an attack where to happen, India would not be expected to display a weak-kneed gesture, as PM Modi's policy is that of a tough and powerful approach in defence vis-à-vis both Pakistan and China. This has already been made evident by its retaliation for the Fidayeen attack at Uri brigade headquarters by Jaish-e-Muhammad in 2016[26]. It has now become evident that if Pakistan continues to harbour terrorist groups against India as its strategic assets, there will be no military restraint by India as long as Modi is in power, who will respond with massive retaliation. In its fragile economic condition, Pakistan will not be able to sustain a long-drawn war effort[27].

On the other hand, Afghanistan, which has been the other focus of Pakistan's proxy groups, is now undergoing a process which could result in a major organisational shift. The Taliban insurgent movement has been able survive this long due to the sanctuary and support provided by Pakistan[28]. Furthermore, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba's participation in the Afghan insurgency furthered the Pakistani military's goal of having a friendly, anti-India partner on its western border[29]. The development and outcome of the intra-Afghan talks will determine the continued use of proxies in the country. However, we can realistically assume that, at least in the near future, radical groups will maintain some degree of activity in Afghanistan.

It is highly unlikely that the Pakistani intelligence establishment will stop engaging with radical groups, as it sees in them a very useful strategic tool for achieving its security goals. However, Pakistan's plausible deniability approach will come into question, as its close ties with Lashkar-e-Tayyiba make it increasingly hard for it to deny involvement in its acts with any credibility. Regarding India, any kind of offensive from this group could result in a large-scale conflict. This is precisely the most likely scenario to occur, as Modi's history with Lashkar-e-Tayyiba and their twelve-year-long "hiatus" from impactful attacks could propel the organisation to take action that will impact the whole region.

2. DRUG TRAFFICKING

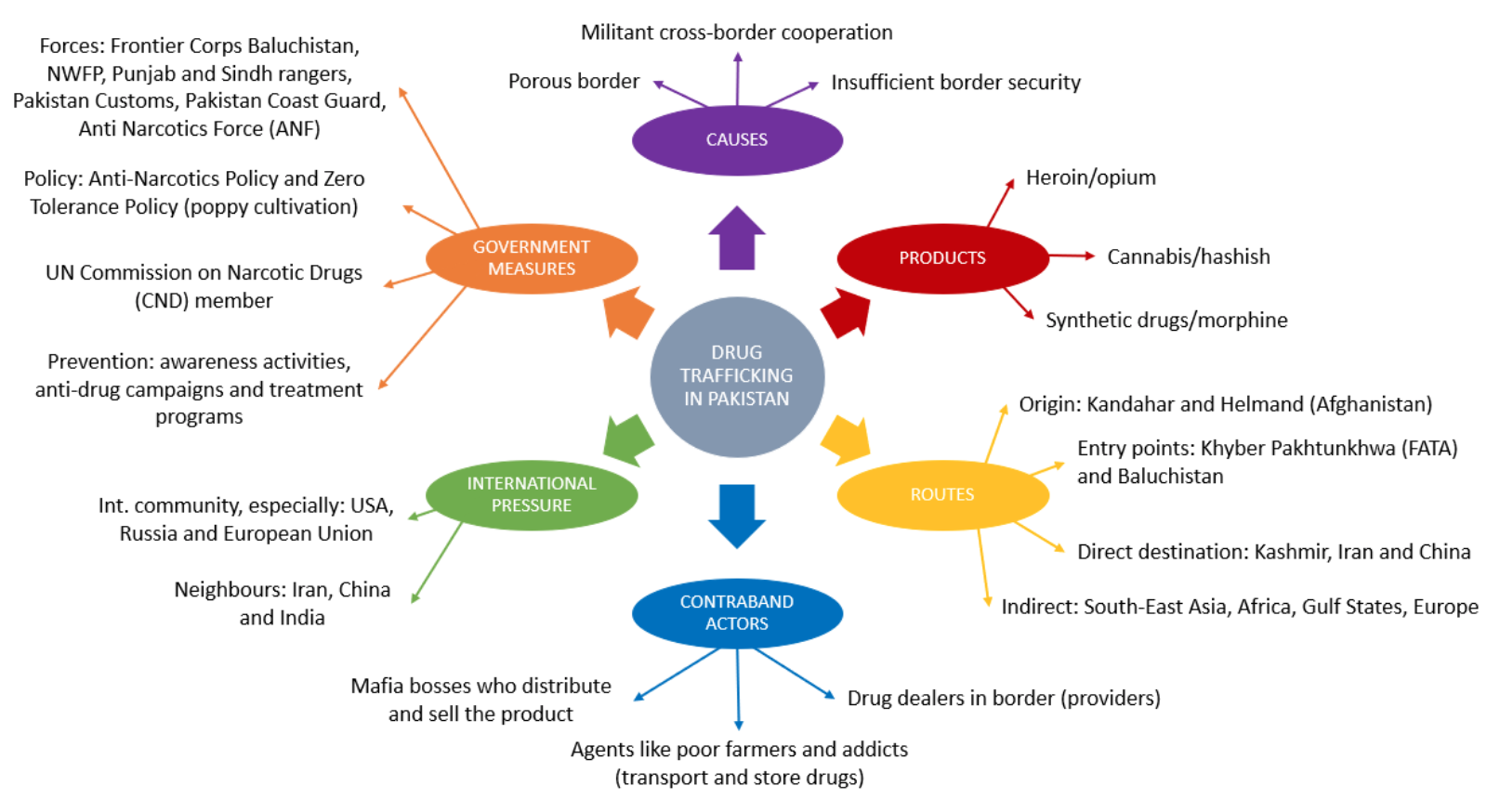

Drug trafficking constitutes an important problem for Pakistan. It originates in Afghanistan, from where thousands of tonnes are smuggled out every year, using Pakistan as a passageway to provide the world with heroin and opioids[30]. The following concept map has been elaborated with information from diverse sources[31] to present the different aspects of the problem aimed to better comprehend the complex situation.

Afghanistan, one of the world's largest heroin producers, has supplied up to 60% and 80% of the U.S. and European markets, respectively. The landlocked country takes advantage of its blurred border line, and the remoteness and inaccessibility of the sparsely populated bordering regions with Pakistan, using it as a conduit to send its drugs globally. The Pakistani government is under a lot of pressure from the international community to fight and minimise drug trafficking from its territory.

Pakistan feels a special kind of pressure from the European Union, as its GSP+ status could be affected if it does not control this problem. The GSP+ is dependent on the implementation of 27 international conventions related to human rights, labour rights, protection of the environment and good governance, including the UN Convention on Fighting Illegal Drugs[32]. Pakistan was granted GSP+ status in 2014 and has shown commitment to maintaining ratifications and meeting reporting obligations to the UN Treaty bodies[33]. However, one of the aspects of the scheme is its "temporary withdrawal and safeguard" measure, which means the preferences can be immediately withdrawn if the country is unable to control drug trafficking effectively[34]. This has not been the case, and the EU has recognised Pakistan's efforts in the fight on drugs; the UN has also removed it from the list of cannabis resin production countries[35]. Anti-corruption frameworks have been strengthened, along with legislation review and awareness building, but they have been advised that better coordination between law enforcement agencies is needed[36].

The GSP+ status is very important to Pakistan, as the European Union is their first trade partner, absorbing over a third of their total exports in 2018, followed by the U.S., China and Afghanistan[37]. The Union can use this as leverage to obtain concessions from Pakistan. However, the approach they have taken so far has been of collaboration in many areas, including transnational organised crime, money laundering and counter-narcotics[38]. In this sense, the EU ambassador to Pakistan recently stated that the new Strategic Engagement Plan of 2019 would "further boost their relations in diverse fields"[39].

Even with combined efforts, eradicating the drug trafficking problem in Pakistan has proven to be very difficult. This is because production of the drug is not done in its territory, and even if border patrols are strengthened, it will be very hard to stop drugs from coming in from its neighbour if the Afghan government doesn't take appropriate measures themselves.

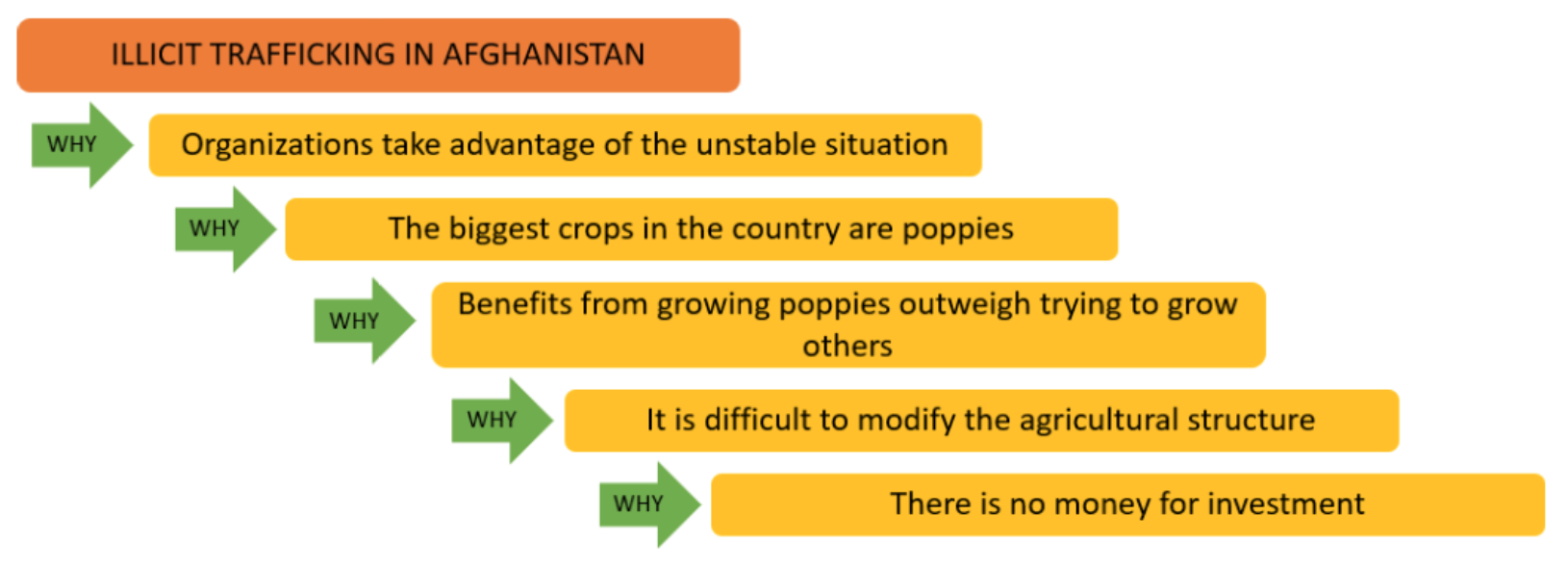

A "5 whys" exercise has led us to understand that the root cause of the problem is the fact that most farmers in Afghanistan are too poor to turn to different crops. A nearly two decade war has ravaged the country's land, leaving opium crops, which are cheaper and easier to maintain, as the only option for most farmers in this agrarian nation. A substantial investment in the country's agriculture to produce more economic options would be needed if any serious advance is expected to be made in stopping illegal drug trafficking. These investments will have to be a joint effort of the international community, and funding for the government will also be necessary, if stability is to be reached. Unless this is done, opium will likely remain entangled in the rural economy, the Taliban insurgency, and the government corruption whose sum is the Afghan conundrum.[40]. And as long as this does not happen, it is highly unlikely that Pakistan will be able to make any substantial progress in its effort to fight illicit drugs.

[1] Khurshid Khan and Afifa Kiran, "Emerging Tendencies of Radicalization in Pakistan," Strategic Studies, vol. 32, 2012.

[2] Hassan N. Gardezi, "Pakistan: The Power of Intelligence Agencies," South Asia Citizenz Web, 2011, http://www.sacw.net/article2191.html.

[3] Madiha Afzal, "Saudi Arabia's Hold on Pakistan," 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/research/saudi-arabias-hold-on-pakistan/.

[4] Gardezi, "Pakistan: The Power of Intelligence Agencies."

[5] Ibid.

[6] Myriam Renaud, "Pakistan's Plan to Reform Madrasas Ignores Why Parents Enrol Children in First Place," The Globe Post, May 20, 2019, https://theglobepost.com/2019/05/20/pakistan-madrasas-reform/.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Drazen Jorgic and Asif Shahzad, "Pakistan Begins Crackdown on Mlitant Groups amid Global Pressure," Reuters, March 5, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-kashmir-pakistan-un/pakistan-begins-crackdown-on-militant-groups-amid-global-pressure-idUSKCN1QM0XD.

[9] Saad Sayeed, "Pakistan Plans to Bring 20,000 Madrasas under Government Control," Reuters, April 29, 2019.

[10] Renaud, "Pakistan's Plan to Reform Madrasas Ignores Why Parents Enrol Children in First Place".

[11] International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clininc (Stanford Law Review) and Global Justice Clinic (NYE School of Law), "Living Under Drones: Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan," 2012, https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/default/files/publication/313671/doc/slspublic/Stanford_NYU_LIVING_UNDER_DRONES.pdf.

[12] Saba Noor, "Radicalization to De-Radicalization: The Case of Pakistan," Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 5, no. 8 (2013): 16-19.

[13] Muhammad Iqbal Roy and Abdul Rehman, "Pakistan's Counter Terrorism Strategy (2001-2019): Evolution, Paradigms, Prospects and Challenges," Journal of Politics and International Studies 5, no. July-December (2019): 1-13.

[14] Madiha Afzal, "A Country of Radicals? Not Quite," in Pakistan Under Siege: Extremism, Society, and the State (Brookings Institution Press, 2018), 208, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/chapter-one_-pakistan-under-siege.pdf.

[15] Ibid.

[16] John Crisafulli et al., "Recommendations for Success in Afghanistan," 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep20107.7.

[17] Tricia Bacon, "The Evolution of Pakistan's Lashkar-e-Tayyiba," Orbis, no. Winter (2019): 27-43.

[18] Susannah George and Shaiq Hussain, "Pakistan Hopes Its Steps to Fight Terrorism Will Keep It off a Global Blacklist," The Washington Post, February 21, 2020.

[19] Husain Haqqani, "FAFT's Grey List Suits Pakistan's Jihadi Ambitions. It Only Worries Entering the Black List," Hudson Institute, February 28, 2020.

[20] Bacon, "The Evolution of Pakistan's Lashkar-e-Tayyiba."

[21] Ibid.

[22] Farhan Zahid, "Profile of Jaish-e-Muhammad and Leader Masood Azhar," Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 11, no. 4 (2019): 1-5, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26631531.

[23] Tricia Bacon, "Preventing the Next Lashkar-e-Tayyiba Attack," The Washington Quarterly 42, no. 1 (2019): 53-70.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Abhinav Pandya, "The Future of Indo-Pak Relations after the Pulwama Attack," Perspectives on Terrorism 13, no. 2 (2019): 65-68, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26626866.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Crisafulli et al., "Recommendations for Success in Afghanistan."

[29] Bacon, "The Evolution of Pakistan's Lashkar-e-Tayyiba."

[30] Alfred W McCoy, "How the Heroin Trade Explains the US-UK Failure in Afghanistan," The Guardian, January 9, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jan/09/how-the-heroin-trade-explains-the-us-uk-failure-in-afghanistan.

[31] Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray and Dr. Shanthie Mariet D Souza, "The Afghanistan-India Drug Trail - Analysis," Eurasia Review, August , https://www.eurasiareview.com/02082019-the-afghanistan-india-drug-trail-analysis/; Mehmood Hassan Khan, "Kashmir and Power Politics," Defence Journal 23, no. 2. 2 (2019); McCoy, "How the Heroin Trade Explains the US-UK Failure in Afghanistan"; Pakistan United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Country Office, "Illicit Drug Trends in Pakistan," 2008, https://www.unodc.org/documents/regional/central-asia/Illicit Drug Trends Report_Pakistan_rev1.pdf; "Country Profile - Pakistan," United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2020, https://www.unodc.org/pakistan/en/country-profile.html.

[32] European Commission, "Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP)," 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/development/generalised-scheme-of-preferences/.

[33] High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, 'The EU Special Incentive Arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance ('GSP+') Assessment of Pakistan Covering the Period 2018-2019' (Brussels, 2020).

[34] Dr. Zobi Fatima, "A Brief Overview of GSP+ for Pakistan," Pakistan Journal of European Studies 34, no. 2 (2018), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333641020_A_BRIEF_OVERVIEW_OF_GSP_FOR_PAKISTAN.

[35] High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, "The EU Special Incentive Arrangement for Sustainable Development and Good Governance ('GSP+') Assessment of Pakistan Covering the Period 2018-2019".

[36] Fatima, "A Brief Overview of GSP+ for Pakistan."

[37] UN Comtrade Analytics, "Trade Dashboard," accessed March 27, 2020, https://comtrade.un.org/labs/data-explorer/.

[38] European External Action Services, 'EU-Pakistan Five Year Engagement Plan' (European Union, 2017), https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu-pakistan_five-year_engagement_plan.pdf; European Union External Services, 'EU-Pakistan Strategic Engagement Plan 2019' (European Union, 2019), https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eu-pakistan_strategic_engagement_plan.pdf.

[39] "EU Ready to Help Pakistan in Expanding Its Reports: Androulla," Business Recorder, October 23, 2019.

[40] McCoy, "How the Heroin Trade Explains the US-UK Failure in Afghanistan".

![Propaganda poster extolling Gaddafi, near Ghadames, 2004 [Sludge G., Wikipedia]. Propaganda poster extolling Gaddafi, near Ghadames, 2004 [Sludge G., Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/libia-cronologia-blog.jpg)

Propaganda poster extolling Gaddafi, near Ghadames, 2004 [Sludge G., Wikipedia].

ESSAY / Paula Mora

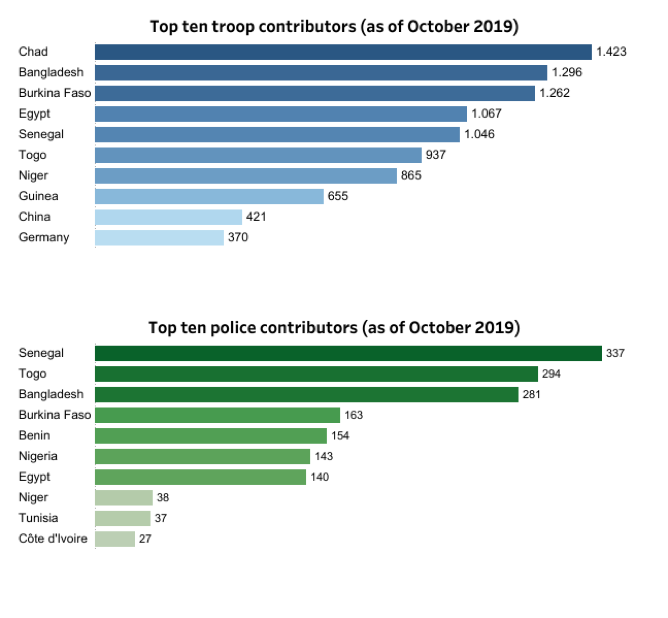

On 20 October 2011, Colonel Muammar Muhamad Abu-Minyar al-Qadhafi was assassinated, bringing an end to a dictatorial regime that lasted more than forty years. That date signified hope, freedom and democracy, or at least those were the aspirations of many of those who contributed to change in Libya. However, the reality today, nine years later, is almost unimaginable for those rebels who on 23 October 2011 thought their children could grow old in a democracy. The civil war that the country has suffered since then has led to the disintegration of the nation. To understand this, it is paramount to understand the very nature of Libyan political power, which is totally different from that of its neighbours and former metropolises: tribalism.

Libyan tribalism has three characteristics: it is contractual, as it is based on permanent negotiations; the territorial instructions of the peoples have been moving towards the cities, but the ties have not been loosened; and the territorial extension of these peoples goes beyond Libya's borders. Ninety percent of Libya's territory is made up of desert, which has allowed tribal power to persist. The original peoples have fought, and continue to fight, for territorial control and harmony of their territories, which is achieved through traditional alliances renegotiated from time to time between the three main regions of the country: Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezran.

Tuareg tropism

Bedouin culture and mythology from pre-colonial trans-Saharan cave times explain why Qadhafi focused his policy on the Sahara and North Africa. These peoples saw the desert as a means of communication, not as an obstacle or a border. Under the dictatorship, Berber customs and speech were protected and promoted.

The Tuareg are a Berber people with a nomadic tradition spread over five African countries: Algeria, Burkina Faso, Libya, Mali and Niger. They have their own language and customs. In Libya, they occupy the south-western territory along the borders of Algeria, Tunisia and Niger. The dictator proclaimed on numerous occasions his affinity with these people, even claiming to belong to this lineage on his mother's side. He considered them allies of his pan-Africanist project .

Gaddafi did not see himself as the leader of the movement, but as a "guide" of the revolution. Over time, however, this revolutionary vision was tempered by a realist and pacifying vision. This change was mainly due to the Tuareg's inability to overcome internal (tribal) divisions and their willingness to abandon the armed struggle. The consequences were that what began as a national and social struggle degenerated into drug and arms trafficking.

Italian colonialism

In April 1881, France occupied Tunisia. This provoked resentment in Italy, as the regency of Tunisia was intended as a natural extension of Italy, given that 55,000 Italians resided in the territory. In view of this status, and to avoid a confrontation with France, Italy then decided to create a Libyan project . In 1882, Italy, Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire created the Triple Alliance. As a consequence, France opposed Italy's Libyan project .

Faced with France's civil service examination plans in Libya, Italy sought redress in the Red Sea and in 1886 tried, unsuccessfully, to conquer Ethiopia. But the Italian nationalism of the time was not about to give up, as it aspired to create "a greater Italy". After the Ethiopian victory, there were only two African alternatives left: Morocco, which had already been practically colonised by France, or the Turkish Regency in Tripoli, which had been in place since 1858.

In the end, Italy opted for the latter and in 1902 sought France's support to carry out its project. Under the Triple Alliance compromise, it offered neutrality on the shared Alpine border in the event of war and Withdrawal to the Moroccan project . Paris was not interested, but in 1908 Russia offered its support to Italy to weaken the Ottoman Empire. Thus began the Italo-Turkish war. The Italian pretext was the alleged mistreatment of the settlers in Libya by the Turkish regime, to which it gave an ultimatum. Under Austro-Hungarian mediation, the Turks agreed to transfer control of Libya to Italy, a move that Italy considered a Turkish manoeuvre aimed only at buying time to prepare for war. On 29 September 1911, Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire. This had important consequences for the Triple Alliance, as Austria-Hungary feared that the Libyan conflict would escalate into a direct conflict with the Ottoman Empire, while Germany was faced with the dilemma of having to choose sides, as it enjoyed good relations with both sides. On 18 October 1912, due to the dangers on several fronts, the Ottoman Empire decided to sign the Treaty of Lausanne-Ouchy, ceding Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and the Dodecanese islands to Italy.

During World War I, Italy was part of the Triple Entente, so the Ottoman Empire did not declare war on it. The threat to Italian control of Libya was not so much among its European enemies, but among the population of Libya itself. Taking advantage of the war, the Sanûsiya (a Muslim religious order founded under the Ottoman Empire and opposed to colonisation) began to attack the Italian army. These rebels gradually gained territory, until Italy's allies went on the offensive. On 21 August 1915, the day Italy switched to the Allies, tactics changed. Although also offering support, Italy's new allies were dealing with insurgencies in their colonies, and were primarily concerned with guarding their borders to prevent insurgents from crossing and spreading pro-independence ideas.

On 17 April 1917, Emir Idris As-Sanûsi, an ally of the Ottoman Empire, realising that Allied victory was near, signed the Pact of Acroma with Italy, whereby Italy recognised the autonomy of Cyrenaica and in exchange the Emir accepted Italian control of Tripolitania.

![Geographical distribution of ethnicities in Libya [Wikipedia]. Geographical distribution of ethnicities in Libya [Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/libia-cronologia-mapa-1.png)

Geographical distribution of ethnicities in Libya [Wikipedia].

Colonial independence

World War II played a role core topic in Africa, encouraging nationalism on the continent. Italy, allied with Germany, attempted between 1940 and 1942 to occupy the Suez Canal across the Libyan border, but goal was not successful.

In 1943, Libya fell into the hands of the Free French (Charles de Gaulle's) and Britain: the former administered Fezán, the latter Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. At the end of the war, with Italy changing sides in the course of the war, Italy proposed a tripartite division of Libya. The United States and the Soviet Union opposed this, and stipulated that the territory would be placed under the aegis of the United Nations (UN). Two political positions were then opposed in Libya: on the one hand, the "progressives", who advocated the creation of a unitary democratic state, and on the other, the original peoples of Cyrenaica, who advocated a kingdom whose leader would be Mohammed Idris As-Sanûsi, the leader of the Sanûsiya.

On 21 November 1949, through Resolution 289, the United Nations set Libya's independence for 1 January 1952. Without taking into account any geographical, historical, religious, cultural and political realities, the UN imposed the birth of a sovereign country made up of the three main independent regions. In 1950, the National Assembly was elected, composed of 60 deputies (20 from each region). On 2 December of the same year, after arduous negotiations, the Assembly agreed that Libya would be a federal monarchy made up of three provinces, with Mohammed Idriss As-Sanûsi as King.

Initially, the Kingdom was able to establish itself given international recognition and the finding oilfields that allowed Libya to become the richest country on the continent. This optimism, however, concealed the fact that Libya's real problem lay within its borders: the country was ruled by the original peoples of Cyrenaica. To balance power, the king decided to appoint Mahmoud el-Montasser, a Tripolitanian, as prime minister.

However, the king made the mistake of basing his monarchy not on the Sanûsiya, but on his tribe, the Barasa. The regime became totalitarian. After pro-Nasser demonstrations, the king banned political parties in 1952 and dismissed more than ten governors, who were replaced by prefects. On the foreign relations front, under Idriss, Libya signed a 20-year alliance with Britain under which the British could use the Libyan military instructions . With the United States, it signed a similar one that granted the Americans permission to build the Wheelus Field base near Tripoli. Finally, it signed a peace treaty with Italy in which the former metropolis agreed to pay reparations as long as Libya protected the property of the 27,000 Italians still living there. These measures brought the kingdom to its doom, as its neighbours and population felt that the king was not showing solidarity with Egypt by aligning himself with the West.

The fall of the monarchy

On 1 September 1969, a coup d'état took place in Libya to overthrow Idriss, who, seriously ill, announced his abdication the following day. The committee Commander of the Revolution (CCR), made up of the officers who had brought about this change of government, abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the Libyan Arab Republic. The military board that established itself in power was composed of a dozen members, mostly from the two main original peoples: the Warfalla and the Maghara. The latter were of Marxist ideology, which led to the regime of Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi.

During the first weeks of government, the new leaders tried to take every possible precaution to avoid British and American intervention. They issued a statement guaranteeing the safety of foreigners' property and promising that the oil companies would not be nationalised. In view of these statements, which were not in line with communism, the United States and the West recognised the new government on 6 September.

The new government's real intentions emerged soon after. Within a month of statement, the Libyan authorities announced that previous treaties relating to the military instructions would have to be renegotiated. They also called for a renegotiation of the taxation of oil companies. Finally, in 1971, a single party was created: the Arab Socialist Union.

Gaddafi's government

On 15 April 1973, almost four years after the coup d'état of '69, Gaddafi gave a speech on speech in which he invited the "popular masses" to take back the power seized by the Arab Socialist Union party. He imposed himself as the head of the country, promoting a cultural and political revolution that proposed, on the one hand, a reform of the institutions with a stricter application of the precepts of the shariaOn the other hand, the idea that the aggressors of the people were the Arab countries allied with the West and Israel.

Gaddafi based his power on a profound tribal recomposition. The first step he took, the day after taking power, distrustful of Cyrenaica and its tribes loyal to King Idriss, was to form an alliance with the people of Hada, seeking to balance the power of the Barasa.

Secondly, he divorced his Turkish-Kouloughli wife, who was an obstacle to the alliances with the peoples he needed to expand his power base. He then married a woman from Firkeche, a segment of the Barasa tribe. This marriage allowed him to build an alliance between the Qadhafa and the large tribes of Cyrenaica linked to the Barasa.

Third, he also built an alliance with the Misrata, a literate elite that subsequently occupied many of the regime's posts. Over time, however, this alliance broke down and led to a growth of hatred towards the colonel that was to play a major role in the revolution that brought down Gaddafi.

Fourthly, after losing Misrata, Gaddafi recomposed his strategy by relying on his own confederation, that of the Awlad Sulaymans, enemies of Misrata since the time of Italian rule. This alliance covered the city of Tripoli and geographically extended the ruler's territory.

Fifth, the ruler's problem would be the result of the previous points: tribal alliances. Fractions of his allies conspired against him in 1973 to attempt a coup d'état. Gaddafi's army, however, prevented it and condemned the ringleaders to death. From this point on, the colonel began to distrust the tribes of this region, Tripolitania, and gradually began to break off relations with them. This would prove fatal to him.

Gaddafi facing the world

International activism under Qadhafi sought the fusion of Arab peoples with the goal aim of creating a transnational caliphate. In 1972, although he did not yet control all of Libyan territory, he contributed to the creation of the Union of Arab Republics (Libya, Egypt and Syria), which was dissolved in 1977. In 1984, it created the Libyan-Moroccan Union, which disappeared two years later. Four other attempts were made: with Tunisia in 1974, with Chad in 1981, with Algeria in 1988 and with Sudan in 1990; none of them succeeded. These attempts at union caused tensions on the continent, particularly with Egypt, with which there was a border dispute from 21-24 July 1977. As a result, the mutual border was closed until March 1989.

As for the rest of the world, the dictator's support for terrorist movements during the 1980s made him enemies, especially the United States, Britain and France. committee Several attacks by the Libyan regime, such as the shooting down of an American plane over the Scottish town of Lockerbie and the assassination of ambassadors, led the UN Security Council in 1992 to adopt a policy of trade and financial sanctions and embargoes. This was compounded by the socialist orientation of the colonel, who nationalised the oil companies and assets of Italian residents on the grounds that they had been stolen during the colonial era.

The fall of the regime

Over time, the regime lost power and national support. This decline was due to the march of the Economics, as citizens benefited from direct hydrocarbon revenues: health care and Education were free, and agriculture was subsidised. In addition, there was the project to create a "great river" (Great Man Made RiverGMMR), of 4,000 kilometres. At summary, the five million inhabitants had an exceptional life, with a GDP per capita of €3,000 in 2011.

The main civil service examination came from Islamic circles, more specifically from the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafist groups (Sunni Islamic ultra-right movement), who from 1995 onwards were radicalised by the financial aid groups from Afghanistan. Their reasons for opposing Gaddafi were the westernisation The country's first major change was to leave behind Tuareg tropism to some extent and turn towards the countries of the North. In the same year, an Islamist rebellion broke out, initiated by the Front for the Liberation of Libya in Cyrenaica. Qadhafi responded with a major crackdown, establishing anti-Islamic laws that punished anyone who did not denounce the Islamists and closing down most of the zawiya (religious schools and monasteries), especially those of the Sanûsiya.

In 2003, Libya acknowledged its involvement in the Lockerbie bombing and undertook to compensate all victims. This led to the lifting of sanctions by the UN Security Council at committee . In December of the same year, the country renounced the production of weapons of mass destruction and in 2004 acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. With these new measures, the regime gradually allied itself with Western countries, which in turn promoted the industrialisation of the country. One example was the treaty signed between Gaddafi and Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, whereby Italy pledged to reimburse Libya $5 billion over a 25-year period, provided that Libya opened up to the Italian market and avoided illegal immigration to Europe.

Libya did not experience "the Arab Spring", as it was suffering from a civil war born in Cyrenaica, which began as an uprising of a Berber minority living near the Tunisian border. Qadhafi, fearful of spoiling the good image he had finally managed to build in the international community, decided not to use military force to re-establish his power in Cyrenaica, but as time went on he had no choice but to do so. This action led to what he already knew: international outcry.

The first country to oppose was Nicolas Sarkozy's France. Under the pretext of humanitarian interference, France, together with the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) countries, decided to destroy the Gaddafi regime. In March 2011 they recognised the Transitional National committee (TNC). The African Union also wanted a change of government, but nevertheless advocated that this should be done through negotiation, in order to avoid negative consequences such as the disintegration of the state.

In February 2011, the colonel was confronted with a triple uprising. In Cyrenaica, by the jihadists (remember the anti-Islamic laws), who were also supported by Turkey and the local mafias, who felt threatened by the Italian-Libyan agreement on migration. In Tripolitania, by the Berbers, who now saw their identity denied in favour of the defence of Arab nationalism. Finally, also in Misrata, the area had a score to settle with the dictator since 1975 (tribal conflict). staff

Gaddafi took preventive measures, such as banning demonstrations and suspending sporting events, and announced pro-people social reforms, thinking that these were grievances that would not go unchallenged. His analytical error was to think that the protest had a social motive, while its reasons were tribal, regional, political and religious subject .

The government was able to control status for a month, until on 15 February the violence escalated into a full-blown civil war.

Foreign interference began on 17 March, when the French foreign minister promoted Resolution 1973 at the UN Security Council's committee , which authorised the creation of a no-fly zone over Libya, as well as the imposition of "necessary measures" to provide protection for civilians. This resolution excluded land occupation, and was supported by the Arab League, with military air support from Qatar.

A few days later, on 21 March, the intervention of NATO countries went beyond the guidelines of Resolution 1973, as Gaddafi's residency program was bombed under the pretext that it served as a command centre. The African Union, supported by Russia, called for an "immediate cessation of all hostilities". For its part, the Arab League reminded NATO that it was deviating from its stated objectives. Western countries, however, did not listen. On 31 March, through his son Saif al-Islam, the colonel proposed a referendum on the establishment of democracy in Libya. NATO was willing to consider his proposals, but the National Transitional committee was adamantly opposed, demanding simply that Gaddafi be removed from power.

mission statement On 16 September, the committee Security Council, through Resolution 2009, created the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL). Its goal was attend to the national authorities for the restoration of security and the rule of law, through the promotion of political dialogue and national reconciliation.

The "liberation" of the country took place on 23 October 2011, when Gaddafi was captured on his way to Fezzan, accompanied by his son. His convoy was attacked by NATO air forces. He was taken prisoner and subsequently lynched by his countrymen. The president of the Transitional National committee , Mustapha Adbel Jalil, then proclaimed himself the new legitimate ruler of the country until new elections.

Libya after Gaddafi

On his first day, the transitional president declared that the sharia would be the basis of the constitution as well as the law, reestablished polygamy and outlawed divorce. The consequences of the civil war were tremendous: they led to the disintegration of the country. Gaddafi's death did not mark the end of the conflict, as the tribal, regional and religious militias that participated in the war held different visions of what the new government should look like, making unification impossible.

Externally, territorial decontrol changed the geopolitics of the Sahara-Sahel region, offering new opportunities for jihadists.

Three periods can be distinguished. The first, between 2011 and 2013, could be considered the time of uncertainty, but also the time of democratic hope and illusion. Despite wars between different peoples over different ideologies (defenders of the old regime versus Muslim fundamentalists defending Islamic traditions) and a territorial proxy war (Cyrenaica versus Tripolitania for the capital of the new state), what appeared to be democratic mechanisms were being put in place.

On 31 October 2011, Tripoli native Abdel Rahim al-Keeb was elected Prime Minister of the transitional government by 26 votes out of 51. Legislative elections were held on 7 July 2012; they were won by the congress General National (CNG), which replaced the Transitional National committee . But the status was far from being consolidated. On 11 September 2012, the American ambassador, John Christopher Stevens, was assassinated by a Salafist group called Ansar al-Sharia.

The second period began in early 2013. Libya was on the path to normalisation through democratic elections and the revival of oil and gas exports. However, the following year saw the beginning of lawlessness and attempts to recompose internal order. The "democratic advances" had not been enough, as the regions were largely autonomous and there was no border security. No one had been able to control Libyan territory in its entirety. Chadian President Idriss Déby, who had already warned of these consequences when the West intervened in the civil war, called the new Libyan status a "Somalisation".

From February 2014 onwards, this lawlessness resulted in a series of resignations of "government" officials due to threats from the country's various militias and protests in front of the NGC, as the government was not dissolved after the expiry of the mandate. On 20 February, elections were held for the 60-member Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution, goal , but only 15% of voters took part. Meanwhile, on 6 March in Rome, at the lecture International on Libya, the Italian foreign minister considered that the main problem was the "overlapping of legitimacy".

The third period took place at the end of 2014, when the so-called 'second Libyan war' began. From 2015 onwards, the Islamic State entered the scene, which changed the Libyan political landscape. The UN created a transitional executive body called the Government of National agreement (GNA), with the goal to steer Libyan politics in this new status. It was formed by the union of the National General congress and the House of Representatives. It is composed of 32 ministers, with Fayez-al Sarraj serving as position president of the Presidential committee and prime minister of the GNA.

Libya then found itself with two parliaments, one in Tripoli, under Islamist control, and the other, recognised by the international community, in Tobruk, Cyrenaica, near the Egyptian border, which had been forced to desist by jihadist forces. This led to the start of another conflict, which is still ongoing today. In Cyrenaica, a confused and multiform war is taking place, involving jihadists and supporters of General Khalifa Haftar, who leads the Libyan National Army (LNA) and opposes both the jihadists and the National agreement government. Through his army, the general launched air strikes against Islamist groups in Benghazi in May, with the goal aim of seizing the parliament. He also accuses Prime Minister Ahmed Maiteg of cooperating with Islamist groups. In June, Maiteg resigned after the Supreme Court ruled that his appointment was illegal.

In 2014, Haftar launched "Operation Dignity" against the Islamists, trying to remove Colonel Moktar Fernana, commander of the military police and elected by Misrata and the Muslim Brotherhood, from power. This mission statement failed due to the power of the different Muslim militias throughout the Tripolitania territory, divided into different areas: there is the city of Misrata, which is jihadist territory under the command of the Muslim Brotherhood; to the west, the militia reigns supreme. Berber Arabic-speaking Zenten; in the capital, the Islamist militia Farj Lybia is in control, while Fezzan and the Grand Sud have become quasi-autonomous territories, where the Tuareg are being fought.

In June 2014, parliamentary elections took place. Islamist parties were defeated, there was a leave turnout due to insecurity and a boycott by the dominant parties, and a clash emerged between forces loyal to the NTC and those in the new parliament or House of Representatives (HoR). Eventually, the National Salvation Government emerged, with Muslim Brotherhood ally Nouri Absuhamain as president.

In July, national security deteriorated severely as a result of several events. Tripoli International Airport was destroyed by fighting between Misrata militia and its Dawa Libya operation against Zintan militia; the HoR moved to Tobruk after the Tripoli Supreme Court (composed of the NTC) dissolved it; the NTC voted itself a replacement for the House of Representatives; Asar al-Sharia took control of Benghazi; and UN envoys left the country due to growing insecurity.

On 29 January 2015, the LNA and its allies in Tripoli declared a ceasefire following the "Libyan Dialogue" organised by the UN in Geneva to encourage reconciliation between the different sides. On 17 December of the same year, the Libyan Political agreement , or agreement Skhirat, promoted by UNSMIL, took place. Its goal was to resolve the dispute between the legitimate House of Representatives, based in Tobruk and al-Bayda, and the NTC, based in Tripoli. A 9-member Presidency committee was set up to form a unity government that would lead to elections in two years. The HoR was to be the sole parliament and would act as such until the elections.

On 30 March 2016, the GNA arrived in Tripoli by sea due to the air blockade. The settlement of the legitimate government led to the UN's return to the territory after two years in April. In addition, the GNA, together with US air forces, liberated Sirte from ISIS in December 2016. However, the LNA continued to gain territory, gaining control of the eastern oil terminals in September.

In July 2017, the LNA drove ISIS out of Benghazi. A year later, it controlled Derna, the last western territory under terrorist groups. On 17 December, Haftar declared the Libyan Political agreement null and void, as elections had not taken place, highlighting the obsolescence of the UN-created Libyan government. The general then began to gain traction in the national and international context: "All institutions created under this agreement are null and void, as they have not gained full legitimacy. Libyans feel that they have lost their patience and that the promised period of peace and stability has become a distant fantasy," Haftar declared.

19 April 2019 was the date on which the Libyan National lecture was to be held in Ghadamas to make progress on agreements and to finalise a date on which the presidential and parliamentary elections would be held. However, days before the convening of lecture was cancelled due to the LNA's "Operation Dignity Flood" with the goal of the "liberation" of the country.

![Correlation of forces in the Libyan civil war, February 2016 [Wikipedia]. Correlation of forces in the Libyan civil war, February 2016 [Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/libia-cronologia-mapa-2.png)

![Correlation of forces in the Libyan civil war, February 2016 [Wikipedia]. Correlation of forces in the Libyan civil war, February 2016 [Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/libia-cronologia-mapa-2-leyenda.png)

Correlation of forces in the Libyan civil war, February 2016 [Wikipedia].

Foreign interference

The current Libyan status is worrying. The international community fears the country could become the next Syria. The National Liberation Army, led by Haftar, is supported by the United Arab Emirates, hoping to stop the advance of the Muslim Brotherhood, which it considers a terrorist organisation. It is also supported by Egypt and Russia, which are interested in controlling the country's energy resources. The National agreement government, with Fayez al-Sarraj as its leader, represents the legitimate government in the eyes of the international community (the UN recognises it). It is supported by the US and EU countries (except France), as well as Turkey and Qatar, which provide military support (especially the Turks). However, the US and the EU defend the maritime borders of Greece and Israel against Turkey's desire project to build gas pipelines across the Mediterranean to supply itself.

The rapprochement between Haftar and France began in 2015. France attempted to transform the LNA into a legitimate actor, assisting it with clandestine operatives, special forces and advisors. On 20 July 2016, Holland's France officially declared its military support for him after the killing of three French special forces soldiers in Benghazi by the GNA, which argued that it was a 'violation of its national sovereignty'. On 25 July 2019, the Paris Summit took place. Macron invited the two leaders for a dialogue on peace and unity. France's main interest is to eradicate terrorism.

On 6 March 2019, the Abu Dhabi agreement brought together the leaders of the most important sides in the Libyan war and emphasised several aspects: Libya as marital status, shortening the transitional period of government, unification of state institutions (such as the Central Bank), cessation of hatred and its incitement, holding presidential and parliamentary elections by the end of the year, peaceful transfer of power, separation of powers and UN follow-up of agreed points. The site meeting sample shows the strong involvement of the United Arab Emirates in this war, especially as an ally of General Haftar. The Persian Gulf country denied supporting the attack on Tripoli that took place on 31 March 2020 by the LNA. However, several Libyan media reported that two military cargo planes arrived at the Emirati Al-Khadim airbase in the east of the Libyan city of Marj from the Sweihan airbase in Abu Dhabi.

On 27 November 2019, the agreement Maritime Border between the GNA and Turkey took place. Turkish President Erdogan and Fayez al-Sarraj signed two memoranda of understanding. They agreed on an 18.6 nautical mile limit as a shared maritime border between Turkey and Libya and signed a military cooperation agreement whereby Ankara would send soldiers and weapons. Instead of creating a new troop, which would take longer, Turkey offered a salary of 200 dollars a month to fight in Libya as opposed to 75 dollars a month to fight in Syria.

The problem with the maritime border is that it ignores the islands of Cyprus and Greece and violates their rights under the 1994 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, although neither of these two countries has gone to the Law of the Sea Tribunal. Turkey's interest lies in the possible presence of oil and natural gas off the southern coast of Crete. The agreement will for the time being last as long as the GNA lasts, in a status of instability to which the unpopularity of military intervention in Turkey also contributes.

On 2 January 2020, the presidents of Algeria and Tunisia met with Khalifa Haftar. Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune insisted that the solution to the Libyan problem must be internal and not depend on the influx of arms brought about by foreign interference. He proposed the creation of new institutions that would allow the organisation of general elections and the establishment of the new instructions of the Libyan democratic state with the approval of the UN.

On 6 January, the LNA took control of Sirte. Sirte is strategic as it is close to Libya's "oil moon"average , a coastal strip where several major oil export terminals are located.

On 12 January, Russia and Turkey declared a truce in Syria and Libya. This agreement was a quid pro quoRussia has greater interests in Syria than in Libya, as it seeks a Mediterranean port, and Turkey, as explained above, wants to build a gas supply system across the Mediterranean Sea from Libya. However, agreement is not being fulfilled, especially in the Libyan scenario. UN envoys allege that both countries continue to provide weapons to the guerrillas.

On 19 January, lecture took place in Berlin, which was an attempt to appease status in the country. The United States, Russia, Germany, France, Italy, China, Turkey and Algeria participated, and expressed a commitment to end political and military interference in the country. Without the intervention of third parties, the country would not be able to sustain a civil war, as none of the sides is strong enough. committee At lecture, the non-compliance with the arms embargo established by the UN Security Council in 2011 was also discussed. The problem is that no power, especially Turkey and Russia, acknowledges its involvement, so there are no responsibilities and no sanctions.

A week later, the first violation of the pact took place. As for the truce, Haftar's government, with the goal aim of retaking the capital, launched an offensive in the direction of the city of Misrata, where an important base of the National agreement government is located. In addition, the UN special mission statement in Libya (UNSMIL) stated that material continues to reach the fighting sides by air.

On 31 March, the EU launched "Operation Irini" ("peace" in Greek). It replaces the 2015 'Operation Sophia', which was goal aimed at combating human trafficking off the Libyan coast. The new operation has changed its main focus to goal , as it will fight to enforce the arms embargo. It also has other secondary tasks such as the control of oil smuggling, the continuation of the Libyan coastguard training and the control of human trafficking through the collection of information with the use of air patrols. This initiative was born above all on the part of Italy, the first country to receive Libyan refugees and therefore concerned about immigration. This leadership is manifested in the development of the operation, as the headquarters are in Rome and the operational direction is at position of Italian Rear Admiral Fabio Agostini. For the time being, it has a duration of one year.

On 5 April, the UN called for a cessation of hostilities to combat Covid-19. It called for a humanitarian truce involving not only the national sides but also foreign forces. The virus claimed the life of Mahmoud Jibril, former prime minister and leader of the rebellion against Gaddafi.

New regional geopolitics and conclusion

We can define the new Libyan geopolitics through the following points. First, the spread of arms throughout the Sahara-Sahel region, the area of old and current conflicts. Second, the border threat felt by Egypt, Algeria and Tunisia due to internal conflict. Finally, the disinterest of the new Libyan authorities in the Greater South, as it has virtually become independent, controlling almost all trade across the Sahara. Al-Qaeda, through sub-groups such as Fajr Libya, is attempting to establish an Islamic State of North Africa in imitation of Iraq. To this end, in the conquered areas, Daesh destroys the tribal paradigm by liquidating tribal chiefs who do not want to ally with them with the aim of terrorising the rest. goal . It is through these practices that all the jihadist militias were able to ally themselves at the end of 2015. Faced with this, the United Nations sponsored Fayez Sarrraj as Prime Minister, who was installed in Tripoli in April 2016.

Libya is a privileged state in terms of natural wealth. However, it has suffered much in its history and continues to do so. It has gone through monarchies, colonisation and dictatorships before finally becoming a failed state. Its political structure is complicated, as it is tribal, which is why none of the political systems have been entirely successful because they have failed to harmonise internal organisations. Today the country consists of three rival governments and hundreds of militias and armed groups that continue to compete for power and control of territory, trade routes and strategic military sites. For status to be resolved, the countries actively involved in the conflict (Russia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar) need to comply with the UN arms embargo. In addition, foreign powers need to increase their understanding of the country in order to be successful in bringing about the best possible solution. Even if Libya is on the verge of becoming the next Syria, there are still opportunities to save status and give the country what it has long lacked: stability.

REFERENCES

Al Jazeera, A. (December 18, 2017). Haftar: Libya's UN-backed government's mandate obsolete.

Al Jazeera, A. (3 April 2020,). Workers in Libya struggle under oil blockade.

Álvaro Sánchez (31 March 2020). The EU launches its mission statement against arms trafficking to Libya. El País. Section - International.

Andrew Seger (2018). Can Libya's Division be healed? Section: Middle East and North Africa, sub-section: Libya.

Assad, A. (2020). Attacks on civilians in Tripoli continue as Haftar receives more support from UAE. The Libya Observer.

Assad, A. (2020). EU launches naval "Operation IRINI" to monitor arms embargo on Libya. The Libya Observer.

BBC World (2020). Libya: why so many international powers are involved in the North African nation. BBC - Section: News World.

Bernand Lugan (2016). Histoire de l'Afrique du Nord. Monaco: Rocher.

Daniel Rosselló (2016). The Libyan Tuaregs: the fighters without a homeland. Think Tank el Órden Mundial - Section: Politics and Society - Subsection: Middle East and Maghreb.

Europa Press. (5 April 2020). The UN reiterates its call for a cessation of hostilities in Libya to combat the coronavirus.

Europa Press (2020). The warring parties in Libya meet for the first time at the UN-sponsored military commission. EuropaPress - Section: International.

Francisco Peregil - Andrés Mourenza (2019). Libya, The New Battleground Between Turkey And Russia. El País- Section: International.

Francisco Peregil (2020). The truce on Libya reached in Berlin becomes a dead letter. El País - Section: International.

Frederic Wehrey (2017). Insecurity and governance challenges in southern Libya. Embassy of Libya, Washington DC. Section: Research, analysis and reflections.

Jawad, R. (20 July 2016). Libya attack: French soldiers die in helicopter crash. BBC News. Retrieved from.

Joanna Apap (2017). Political developments in Libya and prospects of stability. European Parliament Think Tank. Section: Foreign Affairs, subsection: briefing.

Kali Robinson (2020). What's at stake in Libya's War? Council on Foreign Relations. Section: Middle East and North Africa, subsection: Libya.

Karim Mezran - Emily Burchfield (2020). The context of today's Libya crisis and what to watch for. Think Tank Atlantic Council. Section: Politics and Diplomacy - Security and Defense, subsection: Libya.

La Vanguardia (2020). Haftar breaks truce in Libya and UN says embargo violated. La Vanguardia - Section: international.

La Razón (5 April 2020). Coronavirus: Mahmoud Jibril, former Libyan prime minister and leader of rebellion against Gaddafi, dies. Section- International.

Libya Analysis. Accessed February 2020.

Libya Observer: when you need to know. Accessed February 2020.

United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) (2015) Libyan Political Agreement.

María Paz López (2020). No more military interference in Libya. La Vanguardia - Section: International.

Pavel Felgnhauer (2020). Russian-Turkish Accords Start to Unravel in Libya and Syria. The Jamestown Foundation- Section: Regions, Africa.

Reuters (6 January 2020). Hafter's forces claim to have taken control of the Libyan city of Sirte. El País. International Section.

Zaptia, S. (2011). Serraj reveals more details of Abu Dhabi Hafter agreement. Libya Herald.

![Members of the Armed Forces setting up a pavilion at Ifema for the Covid-19 treatment [Defence]. Members of the Armed Forces setting up a pavilion at Ifema for the Covid-19 treatment [Defence].](/documents/10174/16849987/pandemia-ffaa-espana-blog.jpg)

Members of the Armed Forces setting up a pavilion at Ifema for the treatment of Covid-19 [Defence].

COMMENTARY / Salvador Sánchez Tapia*

The Spanish government's declaration of a state of alarm on 15 March as an instrument to fight the spread of COVID 19 has brought with it the not very usual image of soldiers of the Armed Forces (FAS) operating in major cities and roads throughout Spain to cooperate in the fight against the virus.

For most Spaniards, the presence of military units carrying out their missions on public roads is a rarity to which they are not accustomed, with the exception of the relatively frequent activity of the Military Emergency Unit (UME) in support of civil society, which is well known to a public that, in general, values it very positively.

Apart from these performances, it can be said that the image of uniformed soldiers working directly in front of the public is not a common one. This subject of support is not, however, a novelty, and responds to a long tradition of social attendance lent by the military institution to its fellow citizens when called upon to do so.

Several elements in our recent history have contributed to producing what seems to be a certain distancing between Spaniards and their Armed Forces. These include the shift in the Armed Forces' missions abroad with the birth of the democratic regime in 1975; the long years of the fight against ETA terrorism, which led Spain's soldiers to hide their military status from the public in order to safeguard their security; the progressive reduction in the size of the Armed Forces, which eliminated many of the provincial garrisons maintained by the Armies; and the end of military service, which ended up making the Armed Forces unknown to their citizens.