Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs World order, diplomacy and governance .

▲ Special forces (Pixabay)

ESSAY / Roberto Ramírez and Albert Vidal

During the Cold War, Offensive Realism, a theory elaborated by John Mearsheimer, appeared to fit perfectly the international system (Pashakhanlou, 2018). Thirty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, this does not seem to be the case anymore. From the constructivist point of view, Offensive Realism makes certain assumptions about the international system which deserve to be questioned (Wendt, 2008). The purpose of this paper is thus to make a critique of Mearsheimer's concept of anarchy in the international system. The development of this idea by Mearsheimer can be found in the second chapter of his book 'The Tragedy of Great Power Politics'.

The essay will begin with a brief summary of the core tenets of the said chapter and how they relate to Offensive Realism more generally. Afterwards, the constructivist theory proposed by Alexander Wendt will be presented. Then, it will be argued from a constructivist approach that the international sphere is the result of a construction and it does not necessarily lead to war. Next, the different types of anarchies that Wendt presents will be described, as an argument against the single and uniform international system that is presented by Neorealists. Lastly, the essay will make a case for the importance of shared values and ideologies, and how this is oftentimes underestimated by offensive realists.

Mearsheimer's work and Offensive Realism

'The Tragedy of Great Power Politics' has become one of the most decisive books in the field of International Relations after the Cold War and has developed the theory of offensive realism to an unprecedented extent. In this work, Mearsheimer enumerates the five assumptions on which offensive realism rests (Mearsheimer, 2014):

1. The international system is anarchic. Mearsheimer understand anarchy as an ordering principle that comprises independent states which have no central authority above them. There is no "government over governments".

2. Great powers inherently possess offensive military capabilities; which means that there will always be a possibility of mutual destruction. Thus, every state could be a potential enemy.

3. States are never certain of other states' intentions. All states may be benign, but states could never be sure about that, since their intention could change all of a sudden.

4. Survival is the primary goal of great powers and it dominates other motives. Once a state is conquered, any chances to achieve other goals disappear.

5. Great powers are rational actors, because when it comes to international policies, they consider how their behavior could affect other's behavior and vice versa.

The problem is, according to Mearsheimer, that when those five assumptions come together, they create strong motivations for great powers to behave offensively, and three patterns of behavior originate (Mearsheimer, 2007).

First, great powers fear each other, which is a motivating force in world politics. States look with suspicion to each other in a system with little room for trust. Second, states aim to self-help actions, as they tend to see themselves as vulnerable and lonely. Thus, the best way to survive in this self-help world is to be selfish. Alliances are only temporary marriages of convenience because states are not willing to subordinate their interest to international community. Lastly, power maximization is the best way to ensure survival. The stronger a state is compared to their enemies, the less likely it is to be attacked by them. But, how much power is it necessary to amass, so that a state will not be attacked by others? As that is something very difficult to know, the only goal can be to achieve hegemony.

A Glimpse of Constructivism, by Alexander Wendt

According to Alexander Wendt, one of the main constructivist authors, there are two main tenets that will help understand this approach:

The first one goes as follows: "The identities and interests of purposive actors are constructed by these shared ideas rather than given by nature" (Wendt, 2014). Constructivism has two main referent objects: the individual and the state. This theory looks into the identity of the individuals of a nation to understand the interests of a state. That is why there is a need to understand what identity and interests are, according to constructivism, and what are they used for.

i. Identity is understood by constructivism as the social interactions that people of a nation have with each other, which shape their ideas. Constructivism tries to understand the identity of a group or a nation through its historical record, cultural things and sociology. (McDonald, 2012).

ii. A state's interest is a cultural construction and it has to do with the cultural identity of its citizens. For example, when we see that a state is attacking our state's liberal values, we consider it a major threat; however, when it comes to buglers or thieves, we don't get alarmed that much because they are part of our culture. Therefore, when it comes to international security, what may seem as a threat for a state may not be considered such for another (McDonald, 2012).

The second tenet says that "the structures of human association are determined primarily by shared ideas rather than material forces". Once that constructivism has analyzed the individuals of a nation and knows the interest of the state, it is able to examine how interests can reshape the international system (Wendt, 2014). But, is the international system dynamic? This may be answered by dividing the international system in three elements:

a) States, according to constructivism, are composed by a material structure and an idealist structure. Any modification in the material structure changes the ideal one, and vice versa. Thus, the interest of a state will differ from those of other states, according to their identity (Theys, 2018).

b) Power, understood as military capabilities, is totally variable. Such variation may occur in quantitative terms or in the meaning given to such military capabilities by the idealist structure (Finnemore, 2017). For instance, the friendly relationship between the United States (US) and the United Kingdom is different from the one between the US and North Korea, because there is an intersubjectivity factor to be considered (Theys, 2018).

c) International anarchy, according to Wendt, does not exist as an "ordering principle" but it is "what states make of it" (Wendt, 1995). Therefore, the anarchical system is mutable.

The international system and power competition: a wrong assumption?

The first argument will revolve around the following neorealist assumption: the international system is anarchic by nature and leads to power competition, and this cannot be changed. To this we add the fact that states are understood as units without content, being qualitatively equal.

What would constructivists answer to those statements? Let's begin with an example that illustrates the weakness of the neorealist argument: to think of states as blank units is problematic. North Korea spends around $10 billion in its military (Craw, 2019), and a similar amount is spent by Taiwan. But the former is perceived as a dangerous threat while the latter isn't. According to Mearsheimer, we should consider both countries equally powerful and thus equally dangerous, and we should assume that both will do whatever necessary to increase their power. But in reality, we do not think as such: there is a strong consensus on the threat that North Korea represents, while Taiwan isn't considered a serious threat to anyone (it might have tense relations with China, but that is another issue).

The key to this puzzle is identity. And constructivism looks on culture, traditions and identity to better understand what goes on. The history of North Korea, the wars it has suffered, the Japanese attitude during the Second World War, the Juche ideology, and the way they have been educated enlightens us, and helps us grasp why North Korea's attitude in the international arena is aggressive according to our standards. One could scrutinize Taiwan's past in the same manner, to see why has it evolved in such way and is now a flourishing and open society; a world leader in technology and good governance. Nobody would see Taiwan as a serious threat to its national security (with the exception of China, but that is different).

This example could be brought to a bigger scale and it could be said that International Relations are historically and socially constructed, instead of being the inevitable consequence of human nature. It is the states the ones that decide how to behave, and whether to be a good ally or a traitor. And thus the maxim 'anarchy is what states make of it', which is better understood in the following fragment (Copeland, 2000; p.188):

'Anarchy has no determinant "logic," only different cultural instantiations. Because each actor's conception of self (its interests and identity) is a product of the others' diplomatic gestures, states can reshape structure by process; through new gestures, they can reconstitute interests and identities toward more other-regarding and peaceful means and ends.'

We have seen Europe succumb under bloody wars for centuries, but we have also witnessed more than 70 years of peace in that same region, after a serious commitment of certain states to pursue a different goal. Europe has decided to do something else with the anarchy that it was given: it has constructed a completely different ecosystem, which could potentially expand to the rest of the international system and change the way we understand international relations. This could obviously change for the better or for the worse, but what matters is that it has been proven how the cycle of inter-state conflict and mutual distrust is not inevitable. States can decide to behave otherwise and trust in their neighbors; by altering the culture that constitutes the system, they can set the foundations for non-egoistic mind-sets that will bring peace (Copeland, 2000). It will certainly not be easy to change, but it is perfectly possible.

As it was said before, constructivism does not deny an initial state of anarchy in the international system; it simply affirms that it is an empty vessel which does not inevitably lead to power competition. Wendt affirms that whether a system is conflictive or peaceful is not decided by anarchy and power, but by the shared culture that is created through interaction (Copeland, 2000).

Three different 'anarchies'

Alexander Wendt describes in his book 'Social Theory of International Politics' the three cultures of anarchy that have embedded the international system for the past centuries (Wendt, 1999). Each of these cultures has been constructed by the states, thanks to their interaction and acceptance of behavioral norms. Such norms continuously shape states' interests and identities.

Firstly, the Hobbesian culture dominated the international system until the 17th century; where the states saw each other as dangerous enemies that competed for the acquisition of power. Violence was used as a common tool to resolve disputes. Then, the Lockean culture emerged with the Treaty of Westphalia (1648): here states became rivals, and violence was still used, but with certain restrains. Lastly, the Kantian culture has appeared with the spread of democracies. In this culture of anarchy, states cooperate and avoid using force to solve disputes (Copeland, 2000). The three examples that have been presented show how the Neorealist assumption that anarchy is of one sort, and that it drives toward power competition cannot be sustained. According to Copeland (2000; p.198-199), '[...] if states fall into such conflicts, it is a result of their own social practices, which reproduce egoistic and military mind-sets. If states can transcend their past realpolitik mindset, hope for the future can be restored.'

Ideal structures are more relevant than what you think

One of the common assertions of Offensive Realism is that "[...] the desire for security and fear of betrayal will always override shared values and ideologies" (Seitz, 2016). Constructivism opposes such assertion, and brands it as too simplistic. In reality, it has been repeatedly proven wrong. A common history, shared values, and even friendship among states are some things that Offensive Realism purposefully ignores and does not contemplate.

Let's illustrate it with an example. Country A has presumed power strength of 7. Country B has a power strength of 15. Offensive Realism would say that country A is under the threat of an attack by country B, which is much more powerful and if it has the chance, it will conquer country A. No other variables or structures are taken into account, and that will happen inexorably. Such assertion, under today's dynamics is considered quite absurd. Let's put a counter-example: who in earth thinks that the US is dying to conquer Canada and will do so when the first opportunity comes up? Why doesn't France invade Luxembourg, if one take into account how easy and lucrative this enterprise might be? Certainly, there are other aspects such as identities and interests that offensive realism has ignored, but are key in shaping states' behavior in the international system.

That is how shared values (an ideal structure) oftentimes overrides power concerns (a material structure) when two countries that are asymmetrically powerful become allies and decide to cooperate.

Conclusion

After deepening into the understanding that offensive realists have of anarchy in the international system, this essay has covered the different arguments that constructivists employ to face such conception. To put it briefly, it has been argued that the international system is the result of a construction, and it is shared culture that decides whether anarchy will lead to conflict or peace. To prove such argument, the three different types of anarchies that have existed in the relatively recent times have been described. Finally, a case has been made for the importance of shared values and ideologies over material structures, which is generally dismissed by offensive realists.

Although this has not been an exhaustive critique of Offensive Realism, the previous insights may have provided certain key ideas that will contribute to the conversation. Our understanding of the theory of constructivism will certainly shape the way we tackle crisis and the way we conceive international relations. It is then tremendously important that one knows in which cases it ought to be applied, so that we do not rely completely on a particular theory which becomes our new object of veneration; since this may have dreadful consequences.

REFERENCES

Copeland, D. C. (2000). The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism: A Review Essay. The MIT Press, 25, 287–212. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2626757

Craw, V. (2019). North Korea military spending: Country spends 22 per cent of GDP. Retrieved from https://www.news.com.au/world/asia/north-korea-spends-whopping-22-per-cent-of-gdp-on-military-despite-blackouts-and-starving-population/news-story/c09c12d43700f28d389997ee733286d2

D. Williams, P. (2012). Security Studies: An Introduction. (Routledge, Ed.) (2nd ed.).

Finnemore, M. (2017). National Interests in International Society (pp. 6 - 7).

McDonald, M. (2012). Security, the environment and emancipation (pp. 48 - 59). New York: Routledge.

Mearsheimer, J. (2014). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. (W.W. Norton & Co, Ed.). New York.

Mearsheimer. (2007). Tragedy of great power politics (pp. 29 - 54). [Place of publication not identified]: Academic Internet Pub Inc.

Pashakhanlou, A. (2018). Realism and fear in international relations. [Place of publication not identified]: Palgrave Macmillan.

Seitz, S. (2016). A Critique of Offensive Realism. Retrieved March 2, 2019, from https://politicstheorypractice.com/2016/03/06/a-critique-of-offensive-realism/

Theys, S. (2018). Introducing Constructivism in International Relations Theory. Retrieved from https://www.e-ir.info/2018/02/23/introducing-constructivism-in-international-relations-theory/

Walt, S. M. (1987). The Origins of Alliances. (C. U. Press, Ed.). Ithaca.

Wendt, A. (1995). Constructing international politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wendt, A. (2008). Anarchy is what States make of it (pp. 399 - 403). Farnham: Ashgate.

Wendt, A. (2014). Social theory of international politics (p. 1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wendt, A. (2014). Social theory of international politics (p. 29 - 33). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The struggle for power has already started in the Islamic Republic in the midst of US sanctions and ahead a new electoral cycle.

![Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaking to Iranian Air Force personnel, in 2016 [Wikipedia]. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaking to Iranian Air Force personnel, in 2016 [Wikipedia].](/documents/10174/16849987/khamenei-blog.jpg)

▲ Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaking to Iranian Air Force personnel, in 2016 [Wikipedia].

ANALYSIS / Rossina Funes and Maeve Gladin

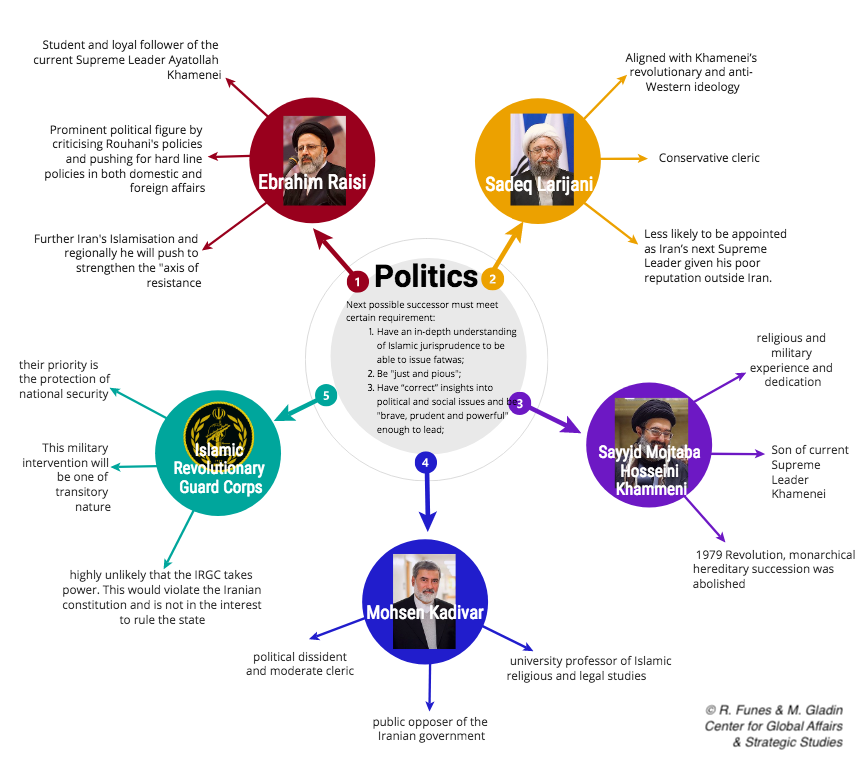

The failing health of Supreme Leader Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei, 89, brings into question the political aftermath of his approaching death or possible step-down. Khamenei's health has been a point of query since 2007, when he temporarily disappeared from the public eye. News later came out that he had a routine procedure which had no need to cause any suspicions in regards to his health. However, the question remains as to whether his well-being is a fantasy or a reality. Regardless of the truth of his health, many suspect that he has been suffering prostate cancer all this time. Khamenei is 89 years old -he turns 80 in July- and the odds of him continuing as active Supreme Leader are slim to none. His death or resignation will not only reshape but could also greatly polarize the successive politics at play and create more instability for Iran.

The next possible successor must meet certain requirements in order to be within the bounds of possible appointees. This political figure must comply and follow Khamenei's revolutionary ideology by being anti-Western, mainly anti-American. The prospective leader would also need to meet religious statues and adherence to clerical rule. Regardless of who that cleric may be, Iran is likely to be ruled by another religious figure who is far less powerful than Khamenei and more beholden to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Additionally, Khamenei's successor should be young enough to undermine the current opposition to clerical rule prevalent among many of Iran's youth, which accounts for the majority of Iran's population.

In analyzing who will head Iranian politics, two streams have been identified. These are constrained by whether the current Supreme Leader Khamenei appoints his successor or not, and within that there are best and worst case scenarios.

Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi

Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi had been mentioned as the foremost contender to stand in lieu of Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei. Shahroudi was a Khamenei loyalist who rose to the highest ranks of the Islamic Republic's political clerical elite under the supreme leader's patronage and was considered his most likely successor. A former judiciary chief, Shahroudi was, like his patron, a staunch defender of the Islamic Revolution and its founding principle, velayat-e-faqih (rule of the jurisprudence). Iran's domestic unrest and regime longevity, progressively aroused by impromptu protests around the country over the past year, is contingent on the political class collectively agreeing on a supreme leader competent of building consensus and balancing competing interests. Shahroudi's exceptional faculty to bridge the separated Iranian political and clerical establishment was the reason his name was frequently highlighted as Khamenei's eventual successor. Also, he was both theologically and managerially qualified and among the few relatively nonelderly clerics viewed as politically trustworthy by Iran's ruling establishment. However, he passed away in late December 2018, opening once again the question of who was most likely to take Khamenei's place as Supreme Leader of Iran.

However, even with Shahroudi's early death, there are still a few possibilities. One is Sadeq Larijani, the head of the judiciary, who, like Shahroudi, is Iraqi born. Another prospect is Ebrahim Raisi, a former 2017 presidential candidate and the custodian of the holiest shrine in Iran, Imam Reza. Raisi is a student and loyalist of Khamenei, whereas Larijani, also a hard-liner, is more independent.

1. MOST LIKELY SCENARIO, REGARDLESS OF APPOINTMENT

1.1 Ebrahim Raisi

In a more likely scenario, Ebrahim Raisi would rise as Iran's next Supreme Leader. He meets the aforementioned requirements with regards to the religious status and the revolutionary ideology. Fifty-eight-years-old, Raisi is a student and loyal follower of the current Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. Like his teacher, he is from Mashhad and belongs to its famous seminary. He is married to the daughter of Ayatollah Alamolhoda, a hardline cleric who serves as Khamenei's representative of in the eastern Razavi Khorasan province, home of the Imam Reza shrine.

Together with his various senior judicial positions, in 2016 Raisi was appointed the chairman of Astan Quds Razavi, the wealthy and influential charitable foundation which manages the Imam Reza shrine. Through this appointment, Raisi developed a very close relationship with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which is a known ideological and economic partner of the foundation. In 2017, he moved into the political sphere by running for president, stating it was his "religious and revolutionary responsibility". He managed to secure a respectable 38 percent of the vote; however, his contender, Rouhani, won with 57 percent of the vote. At first, this outcome was perceived as an indicator of Raisi's relative unpopularity, but he has proven his detractors wrong. After his electoral defeat, he remained in the public eye and became an even more prominent political figure by criticizing Rouhani's policies and pushing for hard-line policies in both domestic and foreign affairs. Also, given to Astan Quds Foundation's extensive budget, Raisi has been able to secure alliances with other clerics and build a broad network that has the ability to mobilize advocates countrywide.

Once he takes on the role of Supreme Leader, he will continue his domestic and regional policies. On the domestic front, he will further Iran's Islamisation and regionally he will push to strengthen the "axis of resistance", which is the anti-Western and anti-Israeli alliance between Iran, Syria, Hezbollah, Shia Iraq and Hamas. Nevertheless, if this happens, Iran would live on under the leadership of yet another hardliner and the political scene would not change much. Regardless of who succeeds Khamenei, a political crisis is assured during this transition, triggered by a cycle of arbitrary rule, chaos, violence and social unrest in Iran. It will be a period of uncertainty given that a great share of the population seems unsatisfied with the clerical establishment, which was also enhanced by the current economic crisis ensued by the American sanctions.

1.2 Sadeq Larijani

Sadeq Larijani, who is fifty-eight years old, is known for his conservative politics and his closeness to the supreme guide of the Iranian regime Ali Khamenei and one of his potential successors. He is Shahroudi's successor as head of the judiciary and currently chairs the Expediency Council. Additionally, the Larijani family occupies a number of important positions in government and shares strong ties with the Supreme Leader by being among the most powerful families in Iran since Khamenei became Supreme Leader thirty years ago. Sadeq Larijani is also a member of the Guardian Council, which vetos laws and candidates for elected office for conformance to Iran's Islamic system.

Formally, the Expediency Council is an advisory body for the Supreme Leader and is intended to resolve disputes between parliament and a scrutineer body, therefore Larijani is well informed on the way Khamenei deals with governmental affairs and the domestic politics of Iran. Therefore, he meets the requirement of being aligned with Khamenei's revolutionary and anti-Western ideology, and he is also a conservative cleric, thus he complies with the religious figure requirement. Nonetheless, he is less likely to be appointed as Iran's next Supreme Leader given his poor reputation outside Iran. The U.S. sanctioned Larijani on the grounds of human rights violations, in addition to "arbitrary arrests of political prisoners, human rights defenders and minorities" which "increased markedly" since he took office, according to the EU who also sanctioned Larijani in 2012. His appointment would not be a strategic decision amidst the newly U.S. imposed sanctions and the trouble it has brought upon Iran. Nowadays, the last thing Iran wants is that the EU also turn their back to them, which would happen if Larijani rises to power. However it is still highly plausible that Larijani would be the second one on the list of prospective leaders, only preceded by Raisi.

|

2. LEAST LIKELY SCENARIO: SUCCESSOR NOT APPOINTED

2.1 Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The IRGC's purpose is to preserve the Islamic system from foreign interference and protect from coups. As their priority is the protection of national security, the IRGC necessarily will take action once Khamenei passes away and the political sphere becomes chaotic. In carrying out their role of protecting national security, the IRGC will act as a support for the new Supreme Leader. Moreover, the IRGC will work to stabilize the unrest which will inevitably occur, regardless of who comes to power. It is our estimate that the new Supreme Leader will have been appointed by Khamenei before death, and thus the IRGC will do everything in their power to protect him. In the unlikely case that Khamenei does not appoint a successor, we believe that there are two unlikely options of ruling that could arise.

The first, and least likely, being that the IRGC takes rule. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that the IRGC takes power. This would violate the Iranian constitution and is not in the interest to rule the state. What they are interested in is having a puppet figure who will satisfy their interests. As the IRGC's main role is national security, in the event that Khamenei does not appoint a successor and the country goes into political and social turmoil, the IRGC will without a doubt step in. This military intervention will be one of transitory nature, as the IRGC does not pretend to want direct political power. Once the Supreme Leader is secured, the IRGC will go back to a relatively low profile.

In the very unlikely event that a Supreme Leader is not predetermined, the IRGC may take over the political regime of Iran, creating a military dictatorship. If this were to happen, there would certainly be protests, riots and coups. It would be very difficult for an opposition group to challenge and defeat the IRGC, but there would be attempts to overcome it. This would be a regime of temporary nature, however, the new Supreme Leader would arise from the scene that the IRGC had been protecting.

2.2 Mohsen Kadivar

In addition, political dissident and moderate cleric Mohsen Kadivar is a plausible candidate for the next Supreme Leader. Kadivar's rise to political power in Iran would be a black swan, as it is extremely unlikely, however, the possibility should not be dismissed. His election would be highly unlikely due to the fact that he is a board member critic of clerical rule and has been a public opponent of the Iranian government. He has served time in prison for speaking out in favor of democracy and liberal reform as well as publicly criticizing the Islamic political system. Moreover, he has been a university professor of Islamic religious and legal studies throughout the United States. As Kadivar goes against all requirements to become successor, he is highly unlikely to become Supreme Leader. It is also important to keep in mind that Khamenei will most likely appoint a successor, and in that scenario, he will appoint someone who meets the requirements and of course is in line with what he believes. In the rare case that Khamenei does not appoint a successor or dies before he gets the chance to, a political uprising is inevitable. The question will be whether the country uprises to the point of voting a popular leader or settling with someone who will maintain the status quo.

In the situation that Mohsen Kadivar is voted into power, the Iranian political system would change drastically. For starters, he would not call himself Supreme Leader, and would instill a democratic and liberal political system. Kadivar and other scholars which condemn supreme clerical rule are anti-despotism and advocate for its abolishment. He would most likely establish a western-style democracy and work towards stabilizing the political situation of Iran. This would take more years than he will allow himself to remain in power, however, he will probably stay active in the political sphere both domestically as well as internationally. He may be secretary of state after stepping down, and work as both a close friend and advisor of the next leader of Iran as well as work for cultivating ties with other democratic countries.

2.3 Sayyid Mojtaba Hosseini Khamenei

Khamenei's son, Sayyid Mojtaba Hosseini Khamenei is also rumored to be a possible designated successor. His religious and military experience and dedication, along with being the son of Khamenei gives strong reason to believe that he may be appointed Supreme Leader by his father. However, Mojtaba is lacking the required religious status. The requirements of commitment to the IRGC as well as anti-American ideology are not questioned, as Mojtaba has a well-known strong relationship with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Mojtaba studied theology and is currently a professor at Qom Seminary in Iran. Nonetheless, it is unclear as to whether Mojtaba's religious and political status is enough to have him considered to be the next Supreme Leader. In the unlikely case that Khamenei names his son to be his successor, it would be possible for his son to further commit to the religious and political facets of his life and align them with the requirements of being Supreme Leader.

This scenario is highly unlikely, especially considering that in the 1979 Revolution, monarchical hereditary succession was abolished. Mojtaba has already shown loyalty to Iran when taking control of the Basij militia during the uproar of the 2009 elections to halt protests. While Mojtaba is currently not fit for the position, he is clearly capable of gaining the needed credentials to live up to the job. Despite his potential, all signs point to another candidate becoming the successor before Mojtaba.

3. PATH TO DEMOCRACY

Albeit the current regime is supposedly overturned by an uprising or new appointment by the current Supreme Leader Khamenei, it is expected that any transition to democracy or to Western-like regime will take a longer and more arduous process. If this was the case, it will be probably preceded by a turmoil analogous to the Arab Springs of 2011. However, even if there was a scream for democracy coming from the Iranian population, the probability that it ends up in success like it did in Tunisia is slim to none. Changing the president or the Supreme Leader does not mean that the regime will also change, but there are more intertwined factors that lead to a massive change in the political sphere, like it is the path to democracy in a Muslim state.

[Francis Fukuyama, Identity. The demand for dignity and the politics of resentment. Deusto, Barcelona, 2019. 208 p.]

review / Emili J. Blasco

|

The democratic deterioration we are seeing in the world today is generating a literature of its own, like that which, on the opposite phenomenon, arose with the democratic springtime experienced after the fall of the Berlin Wall (what Huntington called the third wave of democratization). In that moment of optimism, Francis Fukuyama popularized the idea of the "end of history" -democracy as the final written request in the evolution of human institutions-; today, in this democratic autumn, Fukuyama warns in a new essay of the risk that identity, stripped of liberal safeguards, will phagocytize other values if it remains in the hands of resurgent populist nationalism.

The warning is not new. Huntington, who in 1996 published his Clash of Civilizations, highlighted the driving power of nationalism, was not moved by it; then, in recent years, various authors have referred to the recession of the democratic tide. Fukuyama quotation the expression of Larry Diamond "democratic recession", noting that compared to the leap made between 1970 and the beginning of the new millennium (from 35 to 120 electoral democracies), today the issue has decreased.

The last famous theorist of the International Office to write about this was John Mearsheimer, who in The Great Delusion notes how the world today realizes the naivety of thinking that the liberal architecture was going to dominate the domestic and foreign policy of nations. For Mearsheimer, nationalism is once again emerging strongly as an alternative. This had already been observed just after the decomposition of the Eastern Bloc and the USSR, with the Balkan war as a paradigmatic example, but the democratization of Central and Eastern Europe and its rapid entry into NATO led todelusion.

It has been the personality and policies of the current inhabitant of the White House that has put some American thinkers, including Fukuyama, on alert. "This book would not have been written if Donald J. Trump had not been elected president in November 2016," warns the Stanford University professor, director of his Center on Democracy, development and the Rule of Law. In his view, Trump "is both a product and a contributor to democratic decline" and is an exponent of the broader phenomenon of populist nationalism.

Fukuyama defines populism in terms of its leaders: "Populist leaders seek to use the legitimacy conferred by democratic elections to consolidate their power. They claim a direct and charismatic connection with the people, who are often defined in narrow ethnic terms that exclude important parts of the population. They dislike institutions and seek to undermine the checks and balances that limit a leader's power staff in a modern liberal democracy: courts, parliament, independent media and a non-partisan bureaucracy."

It is probably unfair to hold against Fukuyama some conclusions of The End of History and the Last Man (1992), a book often misinterpreted and taken out of his theoretical core topic . The author has then further concretized his thinking on the institutional development of social organization, especially in his titles Origins of Political Order (2011) and Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Present Day (2014). Already in the latter he pointed to the risk of regression, particularly in view of the polarization and lack of consensus in American politics.

In Identity, Fukuyama considers that non-ethnic nationalism has been a positive force in societies whenever it has been based on the construction of identities around liberal and democratic political values (he gives the example of India, France, Canada and the United States). This is because identity, which facilitates a sense of community and belonging, can contribute to six functions: physical security, quality of government, promotion of economic development , increase in the radius of trust, maintenance of social protection that mitigates economic inequalities, and facilitation of liberal democracy itself.

However -and this may be the book's intended warning-, at a time of recession of liberal and democratic values, these are going to accompany the identity phenomenon less and less, so that in many cases it may change from integrating to excluding.

[Pablo Simón, The modern prince: Democracy, politics and power. discussion, Barcelona 2018, 272 pages]

review / Alejandro Palacios

|

The International Office are guided in each State by a series of leaders and, indirectly, by political parties that are elected more or less democratically by the citizens. Therefore, the high volatility of the vote that we see spreading today in our societies has indirect repercussions on the drift of the international system. This book attempts to review the political systems of some countries to try to explain, in essence, how citizens interact within each political system. The relevance of the book is therefore more than justified.

In fact, by understanding the voting tendencies of citizens, shaped by social divisions and the political system they face, we can get an idea of why such politically radical leaders as Trump or Bolsonaro have emerged. For example, voting in a majoritarian system is not the same as voting in a proportional system. Nor do young people and adults, city dwellers and country dwellers, or men and women vote the same (divisions known as the triple electoral gap).

The author of the book, the Spanish political scientist Pablo Simón, takes as a starting point the Great Recession of 2008, a moment in which new political options began to emerge, encouraged in part by the loss of confidence in both traditional political parties and in the system itself. At the same time, the work attempts to vindicate the importance of the existence of a political science that, as such, is capable of taking a popular assertion about a relevant topic , contrast it empirically and draw mostly general conclusions that help to confirm or disprove that belief.

Pablo Simón also combines the practical analysis of real cases in different countries with theoretical clarifications. This financial aid makes it easy for less familiar readers to follow the explanations of the phenomena he explains reference letter, thus making this book accessible to the general public and not only to an audience specialized in political theory and analysis.

The comparison that the author makes of the different political systems of several countries (he talks about Spain, but also about France, Belgium and the United States, among others) makes this book an excellent guide of enquiry for all those who, without being specifically dedicated to it, want to have a global idea of the party systems in the rest of the world and of the reason for the current political dynamics.

As a counterpoint to the effort of knowledge dissemination there is logically a lesser depth in certain aspects addressed. But it is precisely this informative approach that makes the text pleasant to read, both for the clarity and conciseness of its content (not excessively technical and with theoretical clarifications) and for its length (barely 275 pages). In final, a book which constitutes the perfect guide for all those interested in the functioning of politics in a broad sense, its causes and effects.

Thierry Baudet's electoral surprise and the new Dutch right wing

The Netherlands has seen in recent years not only the decline of some of the traditional parties, but even the new party of the populist Geert Wilders has been overtaken by an even newer training , led by Thierry Baudet, also markedly right-wing but somewhat more sophisticated. The political earthquake of the March regional elections could sweep away the coalition government of the liberal Mark Rutte, who has provided continuity in Dutch politics over the past nine years.

▲ Thierry Baudet, in an advertising spot for his party, Forum for Democracy (FVD).

article / Jokin de Carlos Sola

On March 20, regional elections were held in the Netherlands. The parties that make up the coalition that keeps Mark Rutte in power suffered a strong punishment in all regions, and the same happened with the party of the famous and controversial Geert Wilders. The big winner of these elections was the Forum for Democracy (FvD) party, founded and led by Thierry Baudet, 36, the new star of Dutch politics. These results sow doubts about the future of Mark Rutte's government once the composition of the Senate is renewed next May.

Since World War II, three forces have been at the center of Dutch politics: the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), the Labor Party (PvA) and the liberal People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD). All three accounted for 83% of the Dutch electorate in 1982. Due to the Dutch system of proportional representation, no party has ever had an absolute majority, so there have always been coalition governments. The system also means that, because they are not punished, small parties always achieve representation, thus providing a great ideological variety in Parliament.

Over the years, the three main parties lost influence. In 2010, after eight years in government, the CDA went from 26% and first place in Parliament to 13% and fourth place. This fall brought the VVD to power for the first time under the leadership of Mark Rutte and triggered the entrance of Geert Wilders and his Party for Freedom (PVV), a right-wing populist training , in Dutch politics. Shortly thereafter Rutte formed a Grand Coalition with the PvA. However, this decision caused Labour to drop from 24% to 5% in the 2017 elections. These results meant that both the VVD and Rutte were left as the last element of old Dutch politics.

These 2017 elections generated even greater diversity in Parliament. In them, parties such as the Reformed Party, of Calvinist Orthodox ideology; the baptized 50+, with the goal to defend the interests of retirees, or the DENK party, created to defend the interests of the Turkish minority in the country, achieved representation. However, none of these parties would later be as relevant as the Forum for Democracy and its leader Thierry Baudet.

Forum for Democracy

The Forum for Democracy was founded as a think tank in 2016, led by 33-year-old French-Dutchman Thierry Baudet. The following year the FvD became a party, presenting itself as a conservative or national conservativetraining , and won two MPs in regional elections. Since then it has been growing, mainly at the expense of Geert Wilders and his PVV. One of the main reasons for this is that Wilders is accused of having no program other than the rejection of immigration and the exit from the European Union. As celebrated as it was controversial was the fact that PVV presented its program on only one page. On the contrary, Baudet has created a broad program in which issues such as the introduction of direct democracy, the privatization of certain sectors, the end of military cuts and a rejection of multiculturalism in general are proposed. On the other hand, Baudet has created an image of greater intellectual stature and respectability than Wilders. However, the party has also suffered declines in popularity because of certain attitudes of Baudet, such as his climate change denialism, his relationship with Jean Marie Le Pen or Filip Dewinter, and his refusal to answer whether he linked IQ to race.

Regional Elections

The Netherlands is divided into 12 regions, each region has a committee, which can have between 39 and 55 representatives. Each committee elects both the Royal Commissioner, who acts as the highest authority in the region, and the executive, usually formed through a coalition of parties. The regions have a number of powers granted to them by the central government.

In the provincial elections last March, the FvD became the leading party in 6 out of 12 regions, including North Holland and South Holland, where the cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague, which had been traditional VVD strongholds, are located. In addition to this, it became the party with the most representatives in the whole of the Netherlands. These gains were achieved mainly at the expense of the PVV. Although these results do not guarantee the FvD government in any region, they do give it influence and media coverage, something Baudet has been able to take advantage of.

Several media linked Baudet's victory to the murder a few days earlier in Utrecht of three Dutch nationals by a Turkish citizen, which authorities said was most likely terrorist motivated. However, the FvD had been growing and gaining ground for some time. The reasons for its rise are several: the decline of Wilders, the actions of Prime Minister Rutte in favor of Dutch companies such as Shell or Unilever (business where he previously worked), the erosion of the traditional parties, which in turn damages their allies, and the rejection of certain immigration policies that Baudet linked to the attack in Utrecht. The Dutch Greens have also experienced great growth, accumulating the young vote that previously supported Democrats 66.

|

result of the Dutch regional elections on March 20, 2019 [Wikipedia]. |

Impact on Dutch Policy

The victory of the Baudet party over Rutte's party directly affects the central government, the Dutch electoral system and the prime minister himself. First of all, many media welcomed the results as a evaluation of the Dutch people on Rutte's government. The biggest punishment was for Rutte's allies, the Democrats 66 and the Christian Democratic Appeal, which lost the most support in the regions. Since coming to power in 2010, Rutte has managed to maintain the loyalty of his electorate, but all his allies have ended up being punished by their voters. Therefore, it is possible that Rutte's government will not be able to finish its mandate, if his allies end up turning their backs on him.

The result of the March regionals may have a second impact on the Senate. The Dutch do not appoint their senators directly, but the regional councils elect the senators, so the results of the regional elections have a direct effect on the composition of the upper house. It is therefore very likely that the parties that make up Rutte's government will suffer a major setback in the Senate, which will make it difficult for the Prime Minister to pass his legislative initiatives.

The third consequence directly affects Rutte himself. In 2019 Donald Tusk finishes his second term as president of the European committee and Rutte had a good chance of succeeding him, but with him being the main electoral asset of his party, his departure could sink the VVD. It could then happen as it did with Tusk's departure from Poland, which resulted in a conservative victory a year later.

Whatever the outcome, Dutch politics has in recent years shown great volatility and a lot of movement. In 2016 it was believed that Wilders would win the election and previously that D66 would wrest the Liberal leadership from the VVD. It is difficult to predict which way the wind will turn the mill.

WORKING PAPER / Alejandro Palacios

ABSTRACT

Nowadays we are seeing how countries that during the Cold War did not show great symptoms of growth, today are on their way to becoming the world's largest economies during the period 2030-2045. These countries, "marginalized" by the Western powers in the process of implementing a global economic system, aspire to form an economic order in which they have the decision-making power. This is why South-South alliances among formerly "marginalised" countries predominate, and will continue to prevail in the future. Among these, the ZOPACAS (of which I already wrote about in another article), the IBSA dialogue forum or the BRICS group stand out. Throughout this article, special mention will be made to this last group and how the political and economic interests of the great powers within it, mainly of China, prevail when it comes not only to deciding and coordinating the agreed policies, but also to interceding to accept or not the inclusion of a certain country in the group. In this way, China tries to increase its political and economic ties with the African continent which is crucial in China's strategy to become the leading nation by 2049 (coinciding with the 100th anniversary of its creation).

Download the document [pdf. 438K]

Download the document [pdf. 438K]

![The Forbidden City, in Beijing [MaoNo] The Forbidden City, in Beijing [MaoNo]](/documents/10174/16849987/understanding-china-blog.jpg)

▲ The Forbidden City, in Beijing [MaoNo]

ESSAY / Jakub Hodek

To fully grasp the complexities and peculiarities of Chinese domestic and foreign affairs, it is indispensable to dive into the underlying philosophical ideas that shaped how China behaves and understands the world. Perhaps the most important value to the Chinese is stability. Particularly when one considers the share of unpleasant incidents they have fared.

Climatic disasters have resulted in sub-optimal harvest and could also entail the loss of important infrastructure costing thousands of lives. For instance, the unexpected 2008 Sichuan earthquake resulted in approximately 80.000 casualties. Nevertheless, the Chinese have shown resilience and have been able to continue their day-to-day with relative ease. [1] Still, nature was not the only enemy. Various nomadic tribes such as the Xiong Nu presented a constant threat to the early Han Empire, who were forced to reinvent themselves to protect their own. [2] These struggles only amplified their desire for stability.

All philosophical ideologies rooted in China highlight the benefits of stability over the evil of chaos. [3] In fact, Legalism, Daoism and Confucianism still shape current social and political norms. This is unsurprising as the Chinese interpret stability as harmony and the best mean to achieve development. This affirmation is cultivated from birth and strengthened on all societal levels.

Legalism affirms that "punishment" trumps "rights". Thus, the interest of few must be sacrificed for the good of the many. [4] This translates to phenomenas present in modern China such as censorship of average outlets, autocratic teachers, and rigorous laws to protect "state secrets". Daoism attests to the existence of a cosmological order that determines events. [5] Manifestations of this can be seen in fields of Chinese traditional medicine that deals with feng shui or the flows of energy. Confucianism puts stability as an antecedent of a forward momentum and regulates the relationship between the individual and society. [6] From the Confucianism stems a norm of submission to parental expectations, and the subjugation and blind faith to the Communist Party.

It follows that non-Sino readers of Chinese affairs must consider these philosophical roots when analysing current Chinese events. Seen through that lens, actions such as Xi Jinping declaring stability as an "absolute principle that needs to be dealt with using strong hands[7]," initiatives harshly targeting corrupt Party members, increased censorship on average outlets and the widespread reinforcement of nationalism should not come as a surprise. One needs power to maintain stability.

Interestingly, it seems that this level of scrutiny over the daily lives of average Chinese people has not incited negative feelings towards the Communist Party. One of the explanations behind these occurrences might be attributed to the collectivist vision of society that the Chinese individuals possess. They strongly prefer social harmony over their own individual rights. Therefore, they are willing to trade their privacy to obtain heightened security and homogeneity.

Of course, this way of living contrasts starkly with developed Western societies who increasingly value their individual rights. Nonetheless, the Chinese in no way fell their values to be inferior to the Western ones. They are prideful and portray a sense of exceptionalism when presenting their socioeconomic developments and societal order to the rest of the world. This is not to say that, on occasion, the Chinese have been known to replicate certain foreign practices in an effort to boost their geopolitical presence and economic results.

In relation to this subtle sense of superiority shared by the Chinese, it is important to analyse the political conditionality of engaging with the People's Republic of China (PRC) through economic or diplomatic relations. Although the Chinese government representatives have stated numerous times that, when they establish ties with foreign countries, they do not wish to influence partner-political realities of their recent partner, there are numerous examples that point to the contrary. One only has to look at their One China policy, which has led many Latin American countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taiwan. In a way, this is understandable as most countries zealously protect their vision of the world. As such, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) strategically establishes economic ties with countries harbouring resources they need or that are in need of infrastructure that they can provide. The One Belt One Road initiative represents the economic arm of this vision while their recently increased diplomatic activity, especially in Africa and Latin America, the political one. In short, the People's Republic of China wants to be at the forefront of geopolitics in a multipolar world lacking clear leadership and certainty, at least in the opinion various experts.

One explanation behind this desire for being at the centre stage of international politics hides in the etymology of their own country's name. The term "Middle Kingdom" refers to the Chinese "Zhongguó", where the first character "zhong" means "centre" or "middle" and "guó" means "country", "nation" or "kingdom". [8] The first record of this term, "Zhongguó," can be found in the Book of Documents ("Shujing"), which is one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature. It is a piece which describes ancient Chinese figures and, in some measure, serves as a basis of the Chinese political philosophy, especially Confucianism. Although the Book of Documents dates back to 4th Century A.D., it wasn't until the beginning of the 20th Century when the term "Zhongguó" became the official name of China. [9] While it is true that the Chinese are not the only country that believes they have a higher calling to lead others, China is the only nation whose name uses such a concept.

Such deep-rooted concepts as "Zhongguó", strongly resonates within the social fabric of Chinese modern society and implies a vision of the world order where China is at the centre and leading countries both to the East and West. This vision is embodied in Xi Jinping, the designated "core" leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), who is decisively dictating the tempo of China's effort to direct the country on the path of national rejuvenation. In fact, at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in October 2017, Xi Jinping's speech was centered around the need for national rejuvenation. An objective and a date were set out: "By 2049, China's comprehensive national power and international influence will be at the forefront." [10] In other words, China aims to restore its status as the Middle Kingdom by the year 2049 and become a leading world power.

The full-fleshed grand strategy can be found in "Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in a New Era," a document that is now part of China's constitution and it's as important of a doctrine as Mao Zedong's political theories or anything the CCP's has previously put forth. The Chinese are approaching these objectives promptly and efficiently and, as they have proven in the past, they are capable of great achievements when resources are available. Sure enough, the world is already experiencing Xi Jinping's policies. Recently, Beijing has opted to invest in increased international presence to exert their influence and vision. Starting with continued emphasis on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), massive modernization of the People's Liberation Army (PLA) and aggressive foreign policy.

The migration and political crisis in Europe and Trump's isolationism have given China sufficient space to jump on the international stage and set in motion a new global order, albeit without the will to dynamite the existing one. Xi Jinping managed to renew a large part of the members of CCP's executive bodies and left the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China notably reinforced. He did everything possible to have political capital to push the economic and diplomatic reforms to drive China to the promised land.

Another issue that is given China an opportunity to steal the spotlight is climate change. Especially, after the United States pulled out from the Paris Agreement in June 2017. Last January, Xi Jinping chose the Davos World Economic Forum to show that his country is a solid and reliable partner. Leaning on an economy with clear signs of stability and growth of around 6.7%, many who had predicted its spiralling fall had to listen as the President presented himself as a champion of free trade and the fight against global warming. After expressing its full support for the agreements reached against the emissions of gases at the climate summit held in Paris in 2016, Xi announced the will of "the Middle Kingdom" to guide the new economic globalization.

President Xi plans to achieve his vision with a two-pronged approach. First, a wide-ranging promotion abroad of "Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in a New Era." This is an unknown strategy to the Chinese as there is no precedent of the CCP's ideas being promoted abroad. However, Xi views Western liberal democracy as an impediment to China's rise and wants to offer an alternative in the form of Chinese socialism, which he perceives as practically and theoretically superior. The Chinese model of governing provides a way to catch up with the developed nations and avoid the regression to modern age colonialism. [11] This could turn out to be an attractive proposal to developing nations who might just be lured by China's "benevolent" governance and "generosity" in the form of low-interest loans. Second, Xi wants to further develop and modernize the PLA so that it is capable to ensure national security and maintain Chinese positions in areas where their foreign policy has become more assertive (not to say aggressive) such as in the South China Sea. [12] Confirming that both strong military and economic sustainability are essential to achieve the strategic goal of becoming the centre of their proposed global order by 2049.

If one desires to understand China today, one must look carefully at its origin. What started off as an isolated nation turned out to be a dormant giant that was only waiting to get its home affairs in order before it went for the rest of the world. If there is any lesson behind recent Chinese actions across the political and socioeconomical spectrum is that they want to live up to their name and be at the forefront of the world. This is not to say that they wish an implosion of the current world order, although it is clear, they are willing to use force if need be. It merely implies that they believe their philosophical ideologies to be at least as good as those shared in Western societies while not forgoing what they find useful from them: free trade, service-based economy, developed financial markets, among other things. As things stand, China is sure to make some friends along the way. Especially in developing regions that might be tempted by their tremendous economic success in the last decades and offers of help "with no strings attached." These realities imply that we live in a multipolar which is increasingly heterogenous in connection to values and references that rule it. Therefore, understanding Chinese mentality will prove essential to understand the future of geopolitics.

[1] Daniell, James. "Sichuan 2008: A Disaster on an Immense Scale." BBC News, BBC, 9 May 2013, www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-22398684.

[2] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Xiongnu." Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 6 Sept. 2017, www.britannica.com/topic/Xiongnu.

[3] Creel, Herrlee Glessner. "Chinese thought, from Confucius to Mao Tse-tung." (1953).

[4] Hsiao, Kung-chuan. "Legalism and autocracy in traditional China." Chinese Studies in History 10.1-2 (1976)

[5] Kohn, Livia. Daoism and Chinese culture. Lulu Press, Inc, 2017

[6] Yao, Xinzhong. An introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

[7] Blanchard, Ben. "China's Xi Demands 'Strong Hands' to Maintain Stability Ahead of Congr." Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 19 Sept. 2017.

[8] Concise Spanish-Chinese Dictionary, Chinese Spanish. Beijing, China: Shangwu Yinshuguan. 2007.

[9] Nylan, Michael (2001), The Five Confucian Classics, Yale University Press.

[10] Tuan N. Pham. "China in 2018: What to Expect." The Diplomat, 11 Jan. 2018.

[11]Li, Xiaojun. "Does Conditionality Still Work? China's Development Assistance and Democracy in Africa." Chinese Political Science Review 2.2 (2017): 201-220.

[12] Chase, Michael S. "PLA Rocket Force Modernization and China's Military Reforms." (2018).

Ukrainian Orthodox break with Russia shifts tension between Kiev and Moscow to the religious sphere

While Russia closed the Sea of Azov approaches to Ukraine, at the end of 2018, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church advanced its independence from the Moscow Patriarchate, cutting off an important element of Russian influence on Ukrainian society. In the "hybrid war" posed by Vladimir Putin, with its episodes of counter-offensives, religion is one more sphere of underhand pugnacity.

![Proclamation of autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, with attendance by Ukrainian President Poroshenko [Mykola Lazarenko]. Proclamation of autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, with attendance by Ukrainian President Poroshenko [Mykola Lazarenko].](/documents/10174/16849987/iglesia-ortodoxa-blog.jpg)

▲ Proclamation of autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, with attendance of Ukrainian President Poroshenko [Mykola Lazarenko].

article / Paula Ulibarrena

January 5, 2019 was an important day for the Orthodox Church. In historic Constantinople, today Istanbul, in the Orthodox Cathedral of St. George, the ecclesiastical rupture between the Kievan Rus and Moscow was verified, thus giving birth to the fifteenth autocephalous Orthodox Church, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew I, presided over the ceremony together with the Metropolitan of Kiev, Epiphanius, who was elected last fall by the Ukrainian bishops who wanted to split from the Moscow Patriarchate. After a solemn choral welcome for the 39-year-old Epiphanius, the church leaders placed on a table in the church the tomos (decree), a parchment written in Greek certifying the independence of the Ukrainian Church.

But the one who actually led the Ukrainian delegation was the president of that republic, Petro Poroshenko. "It is a historic event and a great day because we were able to hear a prayer in Ukrainian in St. George's Cathedral," Poroshenko wrote moments later on his account on the social network Twitter.

The event was strongly opposed by the Moscow Patriarchate, which has long been at odds with the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Archbishop Ilarion, head of external relations of the Russian Orthodox Church, compared status to the East-West Schism of 1054 and warned that the current conflict could last "for decades and even centuries".

The great schism

This is the name given to the schism or separation of the Eastern (Orthodox) Church from the Catholic Church of Rome. The separation developed over centuries of disagreements beginning with the moment in which the emperor Theodosius the Great divided the Roman Empire into two parts between his sons, Honorius and Arcadius, upon his death (year 395). However, the actual split did not take place until 1054. The causes are ethnic subject due to differences between Latins and Easterners, political due to the support of Rome to Charlemagne and of the Eastern Church to the emperors of Constantinople but above all due to the religious differences that throughout those years were distancing both churches, both in aspects such as sanctuaries, differences of worship, and above all due to the pretension of both ecclesiastical seats to be the head of Christendom.

When Constantine the Great moved the capital of the empire from Rome to Constantinople, it became known as New Rome. After the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire to the Turks in 1453 Moscow used the name "Third Rome". The roots of this sentiment began to develop during the reign of the Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan III, who had married Sophia Paleologos who was the niece of the last ruler of Byzantium, so that Ivan could claim to be the heir of the collapsed Byzantine Empire.

The different Orthodox churches

The Orthodox Church does not have a hierarchical unity, but is made up of 15 autocephalous churches that recognize only the power of their own hierarchical authority, but maintain doctrinal and sacramental communion among themselves. This hierarchical authority is usually equated to the geographical delimitation of political power, so that the different Orthodox churches have been structured around the states or countries that have been configured throughout history, in the area that emerged from the Eastern Roman Empire, and later occupied the Ottoman Empire.

They are the following churches: Constantinople, the Russian (which is the largest, with 140 million faithful), Serbian, Romanian, Bulgarian, Cypriot, Georgian, Polish, Czech and Slovak, Albanian and American Orthodox, as well as the very prestigious but small churches of Alexandria, Jerusalem and Antioch (for Syria).

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church has historically depended on the Russian Orthodox Church, parallel to the country's dependence on Russia. In 1991, following the fall of communism and the disappearance of the USSR, many Ukrainian bishops self-proclaimed the Kiev Patriarchate and separated from the Russian Orthodox Church. This separation was schismatic and did not gain support from the rest of the Orthodox churches and patriarchates, and in fact meant that two Orthodox churches coexisted in Ukraine: the Kiev Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Church dependent on the Moscow Patriarchate.

However this lack of initial supports changed last year. On July 2, 2018, Bartholomew, Patriarch of Constantinople, declared that there is no canonical territory of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine as Moscow annexed the Ukrainian Church in 1686 in a canonically unacceptable manner. On October 11, the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople decided to grant autocephaly of the Ecumenical Patriarch to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and revoked the validity of the synodal letter of 1686, which granted the right to the Patriarch of Moscow to ordain the Metropolitan of Kiev. This led to the reunification of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and its severance of relations with the Moscow Orthodox Church.

On December 15, in the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Kiev, the Extraordinary Synod of Unification of the three Ukrainian Orthodox Churches was held, with the Archbishop of Pereýaslav-Jmelnitskiy and Bila Tserkva Yepifany (Dumenko) being elected as Metropolitan of Kiev and All Ukraine. On January 5, 2019, in the Patriarchal Cathedral of St. George in Istanbul Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople Bartholomew I initialed the tomos of autocephaly of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.

Does politics accompany division or is it the cause of it?

In Eastern Europe, the intimate relationship between religion and politics is almost a tradition, as it has been since the beginnings of the Orthodox Church. It seems evident that the political confrontation between Russia and Ukraine parallels the schism between the Orthodox Churches in Moscow and Kiev, and is even a further factor adding tension to this confrontation. In fact, the political symbolism of the Constantinople event was reinforced by the fact that it was Poroshenko, and not Epiphanius, who received the tomos from the hands of the Ecumenical Patriarch, whom he thanked for the "courage to take this historic decision". Previously, the Ukrainian president had already compared this fact with the referendum by which Ukraine became independent from the USSR in 1991 and with the "aspiration to join the European Union and NATO".

Although the separation had been years in the making, interestingly, the quest for such religious independence has intensified following Russia's annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea in 2014 and Moscow's support for separatist militias in eastern Ukraine.

The first result was made public on November 3, with a visit by Poroshenko to Fanar, Bartholomew's see in Istanbul, after which the patriarch underlined his support for Ukrainian ecclesiastical autonomy.

Constantinople's recognition of an autonomous Ukrainian church is also a boost for Poroshenko, who faces a tough election degree program in March. In power since 2014, Poroshenko has focused on the religious issue much of his speech. "Army, language, faith," is his main election slogan. In fact, after the split, the ruler stated, "the Ukrainian Orthodox Church is born without Putin and without Kirill, but with God and with Ukraine."

Kiev claims that Moscow-backed Orthodox churches in Ukraine - some 12,000 parishes - are in reality a propaganda tool of the Kremlin, which also uses them to support pro-Russian rebels in the Donbas. The churches vehemently deny this.

On the other side, Vladimir Putin, who set himself up years ago as a defender of Russia as an Orthodox power and counts the Moscow Patriarch among his allies, fervently opposes the split and has warned that the division will produce "a great dispute, if not bloodshed."

Moreover, for the Moscow Patriarchate -which has been rivaling for years with Constantinople as the center of Orthodox power- it is a hard blow. The Russian Church has about 150 million Orthodox Christians under its authority, and with this separation it would lose a fifth of them, although it would still remain the most numerous Orthodox patriarchate.

This fact also has a political twin, as Russia has stated that it will break off relations with Constantinople. Vladimir Putin knows that he is losing one of the greatest sources of influence he has in Ukraine (and in what he calls "the Russian world"): that of the Orthodox Church. For Putin, Ukraine is at the center of the birth of the Russian people. This is one of the reasons, along with Ukraine's important geostrategic position and its territorial extension, why Moscow wants to continue to maintain spiritual sovereignty over the former Soviet republic, since politically Ukraine is moving closer to the West, both to the EU and to the United States.

Nor should we forget the symbolic burden. The Ukrainian capital, Kiev, was the starting point and origin of the Russian Orthodox Church, something that President Putin himself often recalls. It was there that Prince Vladimir, a medieval Slavic figure revered by both Russia and Ukraine, converted to Christianity in 988. "If the Ukrainian Church wins its autocephaly, Russia will lose control of that part of history it claims as the origin of its own," Dr. Taras Kuzio, a professor at Kiev's Mohyla Academy, tells the BBC. "It will also lose much of the historical symbols that are part of the Russian nationalism that Putin advocates, such as the Kiev Caves monastery or St. Sophia Cathedral, which will become entirely Ukrainian. It is a blow to the nationalist emblems that Putin boasts of."

Another aspect to consider is that the Orthodox churches of other countries (Serbia, Romania, Alexandria, Jerusalem, etc.) are beginning to align themselves on one side or the other of the great rift: with Moscow or with Constantinople. It is not clear if this will remain a merely religious schism, if it occurs, or if it will also drag the political power, since it should not be forgotten, as has already been pointed out, that in that area which we call the East there have always been very strong ties between religious and political power since the great schism with Rome.

|

Enthronement ceremony of the erected Patriarch of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church [Mykola Lazarenko]. |

Why now?

The advertisement of the split between the two churches is, for some, logical in historical terms. "After the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the independent Orthodox churches were configured in the 19th century from agreement to the national borders of the countries and this is the patron saint that, with delay, Ukraine is now following", explains the theologian Aristotle Papanikolaou director of the Center of programs of study Orthodox Christians of the University of Fordham, in the United States, in the above mentioned information of the BBC.

It must be seen as Constantinople's opportunity to detract power from the Moscow Church, but above all it is the reaction of general Ukrainian sentiment to Russia's attitude. "How can Ukrainians accept as spiritual guides members of a church believed to be involved in Russian imperialist aggressions?" asks Papanikolau, acknowledging the impact that the Crimean war and its subsequent annexation may have had on the attitude of Constantinople's churchmen.

There is thus a clear and parallel relationship between the deterioration of political relations between Ukraine and Russia and the separation between the Kievan Rus and the Moscow Church. Both Orthodox Churches are closely intertwined, not only in their respective societies, but also in the political spheres and these in turn use for their purposes the important ascendancy of the Churches over the inhabitants of the two countries. In final, the political tension drags or favors the ecclesiastical tension, but at the same time the aspirations of independence of the Ukrainian Church see this moment of political confrontation as the ideal moment to become independent from the Muscovite one.

After four years of board The upcoming elections open up the possibility of a return to a legitimacy too interrupted by coups d'état

Thailand has seen several coups d'état and attempts to return to democracy in its most recent history. The board The military that seized power in 2014 has called elections for March 24. The unsuccessful desire of the king's sister Maha Vajiralongkorn to run for prime minister has drawn global attention to a political system that fails to meet the political aspirations of Thais.

![Bangkok Street Scene [Pixabay] Bangkok Street Scene [Pixabay]](/documents/10174/16849987/tailandia-elecciones-blog.jpg)

▲ Bangkok Street Scene [Pixabay]

article / María Martín Andrade

Thailand is one of the fastest developing ASEAN countries in economic terms. However, these advances come up against a difficult obstacle: the political instability that the country has been dragging since the beginning of the 20th century and that opens a new chapter now, in 2019, with the elections that will take place on March 24. These elections mark a turning point in recent Thai politics, after General Prayut Chan-Ocha staged a coup d'état in 2014 and became Prime Minister of Thailand at the head of the NCPO (committee National Institute for Peace and Order), the board of government formed to run the country.

However, there are many who are sceptical about this new development. entrance of democracy. To begin with, the elections were initially set for 24 February, but shortly afterwards the government announced a change of date and called them for a month later. Some have expressed suspicions about a strategy to prevent the elections from taking place, since, according to the law, they cannot be held once one hundred and fifty days have elapsed since the publication of the last ten organic laws. Others fear that the NCPO has given itself more time to buy votes, while also raising concerns that the Electoral Commission, which is an independent administration, could be manipulated into a success that would in turn be a success. board It's going to be hard for you to insure.

Focusing this analysis on what the future holds for Thai politics, it is necessary to go back to its trajectory in the last century to realize that it follows a circular path.

Coups d'état are not new in the country (1). There have been twelve since the first constitution was signed in 1932. It all responds to an endless struggle between the "military wing", which sees constitutionalism as a Western import that does not quite fit in with the Structures Thai (it also defends nationalism and venerates the image of the king as a symbol of the nation, Buddhist religion and ceremonial life), and the "leftist orbit", originally composed of Chinese and Vietnamese emigrants, which perceives the country's institutionality as similar to that of "pre-revolutionary China" and which throughout the twentieth century expressed itself through guerrillas. To this last ideology must be added the student movement, which since the early 1960s has criticized "Americanization," poverty, the traditional order of society, and the military regime.

With the urban boom that began in the 1970s, the gross domestic product increased fivefold and the industrial sector became the fastest growing, thanks to the production of technological goods and the investments that Japanese companies began to make in the country. During this period, there were coups d'état, such as the one in 1976, and numerous student demonstrations and guerrilla actions. After the 1991 coup and new elections, a new discussion on how to create an efficient political system and a society adapted to globalization.

These efforts were cut short when the economic crisis of 1997 hit, which generated divisions and aroused rejection of globalization, considering it the evil force that had led the country to misery. It is at this point that someone who has since been core topic in Thai politics and who will undoubtedly mark the March elections: Thaksin Shinawatra.