Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Economics, Trade and Technology .

[Eduardo Olier, La guerra económica global. essay sobre guerra y Economics (Valencia: Tirant lo Blanc, 2018), 357 pgs].

review / Emili J. Blasco

War is to geopolitics what economic war is to geoeconomics. Eduardo Olier, the driving force behind another related field in Spain, economic intelligence, has devoted much of his research and professor to the latter two concepts, which are highly dependent on each other.

The book The Global Economic War ( 2018) is a sort of colophon of what could be considered a trilogy, whose previous volumes were Geoeconomics. Las claves de la Economics global (2011) and Los ejes del poder económico. Geopolitics of the global chessboard (2016). Thus, first there was a presentation of geoeconomics, as a specific field inseparable from geopolitics (the use of the Economics by the powers as a new instrument of force), and then a commitment to the concretisation of the different vectors in struggle, with a prolific use of graphs and statistics, unusual in intellectual production in Spanish for a work of knowledge dissemination. This third book is somewhat more philosophical: it has a certain broom-like quality, finishing off or rounding off ideas that had previously appeared in some cases less contextualised in their conceptual framework , and integrating all the reflections into a more compact edifice. With hardly any graphics, here the narrative flows with more attention to the argumentative process.

The global economic war, moreover, puts the focus on confrontation. "Economic warfare is the reverse of political warfare, just as military wars, always political in origin, end up being economic wars," Olier says. He shares the view that "any economic transaction has at its heart a danger of conflict", that "trade is never neutral and contains within it a principle of violence": at final, that "war is the result of a flawed economic exchange ". The author warns that as a country increases its welfare at the same time it boosts its military capacity to try to gain more power. This need not necessarily lead to war, but economic dependence, according to Olier, increases the chances of war. "The possibility of increasing economic benefits from a potential victory increases the likelihood of starting an armed conflict," he says.

Olier is indebted to the development of this discipline carried out in France, where the School of Economic Warfare was born in 1997 as an academic centre attached to the technical school Libre des Sciences Commerciales Appliquées. These programs of study place special emphasis on economic intelligence, which in France is closely linked to the actions of the state secret services in defence of the international position of large French companies, whose interests are closely linked to national imperatives when it comes to strategic sectors. Olier represents in Spain the high school Choiseul, a French think tank dedicated to these same issues.

Among the interesting contributions of The Global Economic War is the dating and interrelation of the successive versions of the internet, globalisation and NATO: the beginning of the Cold War, 1950 (globalisation 1.0 and NATO 1.0); the dissolution of the USSR, 1991 (globalisation 2.0); creation of the internet, 1992 (web 1.0); entrance of Poland in NATO (NATO 2.0); birth of social networks, 2003 (web 2.0); annexation of Crimea by Russia and consolidation of cyberspace in all activities, 2014 (globalisation 3.0, NATO 3.0 and web 3.0). In this schedule he adds at another point the currency war: currency war 1.0 (1921-1936), 2.0 (1967-1987), 3.0 (2010); this is not an outlandish addendum , but very much to purpose, as Olier argues that, if raw materials are one of the keys to economic warfare, currencies "are no less the subject commodity of the Economics, as they can mark who has and who does not have power".

All this reflection is set in the context of a chain of cycles and counter-cycles, where economic and political cycles are interconnected. reference letter Referring to Kondratiev's long cycles, which are renewed every half century, he recalls that the last cycle would have begun in 1993, so that "the expansionary period should last until 2020, before falling and fill in the 50-year cycle, more or less, towards 2040, when a new expansion would begin" (Olier writes this without foreseeing how the current pandemic would, for the time being, reinforce the prediction).

Just as in geopolitics there are a few imperatives, geoeconomics is also governed by some laws, such as those that move directly to the Economics: when there is economic growth, leave unemployment rises and inflation rises, and vice versa; the conflict for a country and its international environment is when Economics goes down, unemployment rises and so does inflation, giving rise to stagflation status .

Geoeconomics as discipline forces us to look squarely at present and future realities, without allowing ourselves to be fobbed off with wishful thinking about the world we would like, which is why the outlook on the European Union ends up being sombre. Olier believes that Europe will experience its instability without revolutions, but with a loss of global power. "The bureaucratisation of the Structures government in Brussels will only help to increase populism. Brexit (...) will be a new silent revolution that will diminish the power of the whole. This will be increased by the different visions and strategies" of the member states. "A circumstance that will give greater power to Russia in Europe, while the United States will look to the Pacific in its staff conflict with China".

In his opinion, only France and Britain, because of their military power, show signs of wanting to participate in the new world order. The other major European countries are left to one side: Germany sample that economic power is not enough, Italy has enough to try not to disintegrate politically... and Spain is "the weakest link in the chain", as was the case just over eighty years ago, when the new order that was taking shape in Europe first confronted the major powers in the Spanish Civil War before the outbreak of the Second World War. Olier warns that "the nirvana of affluent European societies" will be seriously threatened by three phenomena: the instability of internal politics, mass migrations from Africa and demographic ageing that will cause them to lose dynamism.

POLITICAL RISK REPORT / Andrea Izco, Elena López-Doriga and Lucía Sáez

Download the document [pdf. 1MB].

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The purpose of this political risk report is to analyze how stable the political, economic, and social conditions of South Korea are to determine the best approach to invest in this country.

Firstly, regarding the Economic Outlook, the GDP is expected to increase 3.6% in 2021 and 2.8% in 2022 and the government has devoted to get out of the crisis through the Korean-New Deal. Concerning heavy industry, manufacturing, and AI and technology, South Korea is taking action to become a potential leader. In terms of energy, the country's high dependence on energy imports because of its scarcity of natural resources motivates them to move towards renewable energies as well as to maintain its energy security.

Secondly, in relation to South Korea's Social Outlook, the country has shown great social cohesion after the COVID-19 crisis with responsible action by the population. The birth rate is expected to remain very low, but still, the need for immigrants has not been an easy response as nationals feel a certain threat. Regarding religion, the notion of democracy is what brings South Korea closer to the Western World, not too much the notion of Christianity, but even having a democratic system, many Confucian values still remain. It is safe to say that even though Koreans are likely to become less institutionally committed, the decline on religion will be minimal and regarding social stability, there will not be social confrontations between the different groups.

Thirdly, in the Political Outlook we see how South Korea's democracy faces issues concerning the powerful executive connected to a crony capitalism system in which Chaebols have been related to political scandals in the last administrations. However, in the short-term, the government will focus on resolving partner-economic issues rather than taking system reforms, as a new form of populism is emerging claiming for solutions for inequalities and damage caused by modernity. Despite of the little economic progress carried out by the current administration under President Moon, it is likely that his party will win again the next presidential elections in 2022 thanks to the well management of the COVID-19 crisis.

Finally, the Inter-Korean question can be concluded by saying North Korea is not willing to open up and instead takes minimal reforms. Despite of the struggles caused by the crisis and the commitment to dialogue from South Korea under the so-called Sunshine Policy, little progress has been achieved.

[Carlos Lopes, Africa in Transformation: Economic Development in the Age of Doubt (London: Palgrave, 2018), 175 pp.]

REVIEW / Emilija Žebrauskaitė

The emergence of a new discourse about 'Africa rising' is not at all surprising. After all, the continent is home to many fastest-growing economies of the world and the African sub-regions experienced economic growth way above the world average for more than a decade. New opportunities are opening up in the continent and Africa is becoming to be viewed as an attractive opportunity for investments and entrepreneurship.

However, Carlos Lopes views the discourse about 'Africa rising' as a narrative that was created by foreigners interested in the continent and the economic opportunities it offers, without the consideration to the Africans themselves. In his book Africa in Transformation: Economic Development in the Age of Doubt Lopes presents an alternative view of the continent, it's challenges and achievements: an alternative view that is centered on Africans and their needs as opposed to the interests of the foreign investors.

The book describes a wide scope of topics from political to economic to intellectual transformation, all of them focusing on the rethinking of the traditional development models and providing a new, innovative approach to building the continent and its future.

One of the main points Lopes highlights is the importance of the agricultural transformation in Africa as a starting point for industrialization and development. The agricultural sector provides nearly 65% of Africa's population with employment. It is, therefore, one of the most important sectors for the continent. Drawing on historical evidence of other countries successfully climbing out of poverty relying on the transformation of the local agriculture, he comments that while some African countries have managed to increase their agricultural production, comparing to the rest of the world, the progress so far is pretty modest.

Lopes also points out that countries with low agricultural production are less industrialised as well. The solution he offers for Africa's industrialisation starts with agricultural transformation. He argues that the first step is the need for agricultural transformation that would lead to increased labour productivity, which would, in turn, lead to greater access to food per unit of labour, reducing the price of food relative to the income of the worker of the agricultural sector, allowing for the budget surplus to appear and become an impetus for the demand of goods and services beyond the agricultural sector.

While Lopes argues that the increase of Africa's labour productivity is as best "modest" compared to other developing regions of the world, at first glance this statement might seem contradictory to the fact that many African countries are among the fastest-growing economies of the world. However, the critique of Lopes highlights that despite the economic growth of the continent, it did not generate sufficient jobs, nor it was equally distributed across the continent. Furthermore, the growth did not protect African economies from the rocky nature of the commodity exports on which the continent relies, making the growth unstable.

According to Lopes, not only the diversification of the production structures is required, there is a need for the creation of ten million new jobs in order to absorb the immense youth number entering the markets. As the trade liberalisation forced unequal competition upon local African industries, Lopes suggests using smart protectionist measures that are not directly trade-related and therefore outside of the influence of WTO. In the end, the African economy must be internally driven and less dependent, and the policies should focus to protect it.

This leads us to another focus of the book, namely the lack of policy space for African countries. The economic and political theories reflected upon Africa by the developed countries, specifically the US, do not leave enough space for African countries to develop their own policies based on local circumstances and necessities. In cases where the ideas imposed from abroad fail to function in African circumstances, the continent is left without much space for adjustment. Lopes discusses the failure of the Bretton Woods institutions to remain impartial in their policymaking, and the disastrous effect the neo-liberal policies, enforced on the whole world until the crisis of 2008.

While Lopes agrees that the lack of the capability of enforcing the IMF and World Bank policies by the implementing countries contributed to their ineffectiveness, the lack of flexibility from the part of the international organisations to adapt the policies to the regional circumstances and the arrogant denial to admit their inefficiency were the major factors contributing to the negative social impact, namely inequality, that neo-liberalism enhanced in Africa. According to Lopes, now that the trustworthiness of the international financial institutions has decreased, more space is left for Africa to reformulate and enforce its own policies, adapting them to the existing circumstances and needs.

In the end, the book approaches the problems faced by modern-day Africa from a multidisciplinary point of view, discussing topics ranging from ideology and ecology to economy and politics. Carlos Lopes is a loud and confident voice when it comes to the contribution of the 'Africa rising' narrative. While he does not deny the accomplishment of the continent, he is cautious about the narrative that portrays Africa as an economic unit, interesting due to and only because of new economic possibilities that are opening for foreign interests. His alternative is the idea of 'Africa in transformation' - the view that focuses on the growth of the possibilities for the people of Africa and transformation of a continent from an object of someone's exploitation, to a place with its own opportunities and opinions, offering the world new ideas on the most important topic of contemporary international debates.

Javier Blas & Jack Farchy, The World For Sale. Money, Power and the Traders. Who Barter the Earth's Resources (London: Random House Business, 2021) 410 pp.

review / Ignacio Urbasos

In what is probably the first book dedicated exclusively to the world of commodities trading, Javier Blas and Jack Farchy attempt to delve into a highly complex industry characterised by the secrecy and opacity of its operations. With more than two decades of journalistic experience covering the world of natural resources, first for the Financial Times and later for Bloomberg, the authors use valuable testimonies from professionals in the sector to construct an honest account.

The book covers the history of the commodity trading world, beginning with the emergence of small intermediaries responding to the growing need after World War II to supply raw materials to Western economies in their reconstruction processes. The oil nationalisation of the 1960s offered an unprecedented opportunity for these intermediaries to enter a sector that had hitherto been restricted to the traditional oil majors. The new petro-states, now in control of their own oil production, needed someone to buy, store, transport and ultimately sell their oil abroad. This opportunity, coupled with the oil crises of 1973 and 1978, allowed these intermediaries to reap unprecedented spoils: a booming sector with enormous price volatility, which allowed for profits in the millions. With the fall of the Soviet Union and the socio-economic collapse of a large part of the socialist world, companies dedicated to the purchase and sale of raw materials found a new market, with enormous natural resources and without any subject experience in the capitalist market Economics . With the entrance of the 21st century and the so-called " CommoditySupercycle", trading companies enjoyed a period of exorbitant profits in a context of rapid global growth led by China. It is in these last two decades that Vitol, Trafigura, Glencore or Cargill increased their revenues exponentially, with a global presence and managing all commodities, both physically and financially, through subject .

Throughout the different chapters, the authors tackle the complexities of the world of trading without complexes. On many occasions, these companies have enabled countries in crisis to avoid economic collapse by offering financing and the possibility of finding a market for their resources, as in the paradoxical case of Cuba, which threw itself into the arms of Vitol to supply oil in exchange for sugar during the "Special Period". However, the dominant position of these companies vis-à-vis states in an enormously vulnerable status has ended up generating relationships in which the benefits are unequally shared. A paradigmatic case that is exhaustively covered in the book is that of Jamaica in the 1970s, which was heavily indebted and impoverished, when Marc Rich and Company became one of the country's main creditors in exchange for de facto control of the country's bauxite and aluminium mining production. These situations continue today, with Glencore as Chad's largest creditor and a key player in the country's fiscal austerity policies.

Nor do the authors hide the unscrupulousness of these companies in maximising their profits. Thus, they supplied apartheid South Africa with oil or clandestinely sold Iranian crude oil in the midst of the Hostage Crisis. Similarly, these big companies have never had problems dealing with autocrats or being active in major corruption schemes. Nor have environmental scandals been a rarity for these companies, which have been forced to pay millions in compensation for negligent management of toxic products, as in the case of Glencore and the sulphur spill in Akouedo, which resulted in 95,000 victims and the payment of 180 million to the government of Côte d'Ivoire. It is not surprising that many of the executives of these companies have ended up in prison or persecuted by the law, as in the case of Mark Rich, founder of Glencore, who had to live in Spain until he obtained a controversial pardon from Bill Clinton on the last day of his presidency.

There is no doubt that The World For Sale by Javier Blas and Jack Farchy provides a better understanding of a sector as opaque as the commodities trade. An industry dominated by companies with complex fiscal Structures transnational presence and whose activities often remain outside of public scrutiny. As an industry of growing economic and political importance, it is essential to read this book to gain a critical and realistic perspective on an essential part of our globalised Economics .

Spain, although affected, is not as badly affected as other European partners.

The UK's exit from the European Union finally materialised on the last day of 2020. The compromise on fisheries was the last point of the arduous negotiations and the differences were only overcome some conference before the unpostponable deadline. The fisheries agreement reached provides that for five and a half years EU vessels will continue to have access to fish in British waters. Although affected, Spain is not as badly affected as other European partners.

Fishing fleet in the Galician town of Ribeira [Luis Miguel Bugallo].

article / Ane Gil

The Brexit-culminating withdrawalagreement ran aground in its final stretch on the issue of fisheries, despite the fact that the UK's fishing activity in its waters contributes only 0.12% of British GDP.

That discussion, which nearly derailed the negotiations, centred on the delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), the area beyond territorial waters - at a maximum distance from the coast of 200 nautical miles (about 370 kilometres) - in which a coastal country has sovereign rights to explore and exploit, conserve and manage natural resources, whether living or non-living. The UK EEZ is home to fish-rich fishing grounds, which account, with a average of 1.285 million tonnes of fish per year, according to a 2019 study by the European Parliament's Fisheries Committee, for 15% of the EU's total fish catch. Of these catches, only 43% was taken by British fishermen, while the remaining 57% was taken by other EU countries. The European countries that had access to fishing in British waters were Spain, Germany, Belgium, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Ireland and Sweden.

Therefore, the entrance in force of Brexit would mark the UK's withdrawal from the Common Fisheries Policy, which defines the access of European vessels to the Exclusive Economic Zone.

Initial perspectives

During its membership of the EU, the UK was part of the Common Fisheries Policy, whereby all EU member states' fishing fleets have equal access to European waters. In the EU, fishing rights are negotiated annually by the ministers of each member state and national quotas (the amount of fish of each species that each country's fleet can catch) are set using data historical data such as reference letter.

The Spanish fishing fleet followed the negotiations closely, as it had a lot to lose from a bad agreement. On the one hand, a Brexit without agreement could mean a reduction in income of 27 million euros related to fishing in British waters; it would also entail a drastic reduction in hake, megrim and mackerel catches for Spanish fishing boats specialising in these species. On the other hand, the employment would also be affected if the agreement established a drastic reduction in catches. Eighty Spanish vessels have licence to fish in British waters, which means almost 10,000 jobs for work related to this activity.

The negotiations

Until Brexit, British waters and their exploitation were negotiated jointly with the rest of the European Union's maritime areas. Brussels tried to maintain this relationship even if the UK left the EU, so the position of European negotiators focused on preserving the system of fishing quotas that had been in place, for a period of fifteen years deadline . However, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson always ruled out any trade agreement that would grant European vessels access to British waters in exchange for better conditions for British financial services in the single market as offered by Brussels. London wanted to implement a regime similar to the Norwegian one, which negotiates year by year the catches of EU fleets in its waters, with the difference that in the Norwegian case the pact refers to average dozen species, compared to almost a hundred in British waters.

We should bear in mind that the service sector accounts for 80% of the UK's GDP, while fishing activities account for only 0.12%. It is therefore quite clear that London's positions on the fisheries section were more political than economic. Although fishing activities have little impact on the British Economics , the fishing sector does have political importance for the Eurosceptic cause, as regaining control of the waters was one of the promises made in the Brexit referendum. Thus, this issue became a symbol of national sovereignty.

The starting point for the negotiations was the UK government's demand to repatriate up to 80% of the catches in its waters of control, while the EU offered refund to the UK between 15% and 18%. Johnson wanted to keep management from exploiting its waters and to negotiate with the EU as partner preferential. He expressed his initial intention to establish, from January 2021, more frequent negotiations on how to fish in his EEZ. This resulted in a finalagreement which implies that European vessels will continue to be able to fish in British waters for five and a half years, in exchange for refund 25% of the quotas EU vessels fish there, estimated to be worth around 161 million euros. In return, fish products will continue to enter the European market at zero tariff. After this transitional phase, the EU and the UK will have to renegotiate year after year. If the agreement is violated, there are mechanisms in place to ensure compensation, such as tariffs.

Consequences for Spain and its European neighbours

The agreement provoked discontent in the UK fishing industry, which accused Johnson of caving in on this agreement. The National Federation of Fishermen's Organisations expressed disappointment that only marginal changes had been made to quotas and that EU fleets would continue to have access to UK waters up to the six-mile limit. The prime minister responded that the UK could now catch "prodigious amounts of extra fish".

For the time being, the UK has already encountered some problems. The new customs agreement has been causing delays and lorries have to be checked at the borders. With a sudden overproduction, there will not be enough veterinarians to make the necessary export health certificates. Therefore, the new bureaucratic requirements has led to several cases of seafood rotting on the docks before it can be exported to the EU. It is estimated that the fishing industry is losing 1 million pounds per day due to these new requirements, which has caused many fishermen to reduce their daily catches.

But EU fishermen will also be affected, as until now they have been catching fish in British waters with a total annual value of 650 million euros, according to the European Parliament, especially at position from Danish, Dutch and French vessels. In addition, Belgium is one of the countries most affected, as 43% of its catches are taken in British waters; it will now have to reduce its catches by 25% over the next 5 years. Moreover, Belgian fishermen used to land their fish in British ports and then truck it to Belgium. However, this will no longer be possible. Alongside Belgium, other countries that will suffer most from the loss of fishing rights due to Brexit are Ireland, Denmark and the Netherlands.

As for Spain, the fishing sector has acknowledged its unease about the annual negotiation that will take place after the initial five-year period, as well as the consequences for the future distribution of the rest of the fishing quotas, for the Common Fisheries Policy itself, for the exchange of quotas between countries and for the sustainable management of marine stocks. However, in the short term deadline the Spanish fleet does not seem to be so affected in comparison with other European countries.

In fact, the Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Luis Planas, gave a positive assessment of this agreement, considering it a "good agreement, which provides stability and legal certainty". Planas argued that the 25% reduction in the average value of catches by the eight European countries fishing in British waters has limited effects on Spanish fishing activity and, by way of example, he stated that hake catches will only be reduced by 1%. In other words, the current quota of 29.5% would fall to 28.5% in 2026. In addition, other species of greater interest to Spain (such as mackerel, horse mackerel and blue whiting) have not been included in the agreement and there are no reductions in deep-water species in high demand (such as black scabbardfish or grenadiers). In conclusion, Planas said that Spain has only conceded on 17 of the 32 fishery resources allocated to the country. However, it is up to Brussels to go into the details and decide on fishing quotas during the transition period that opened on 1 January, in which the eight countries fishing in British waters will have lower quotas.

In conclusion, Britain now has the ability to dictate its own rules at subject on fishing. By 2026, the UK can decide to completely withdraw access for EU vessels to British waters. But the EU could then respond by suspending access to its waters or imposing tariffs on UK fish exports.

review / Emili J. Blasco

The discipline of "political risk" can be conceived in a restrictive way, as usual, referring to the prospective analysis of disruptions that, by states and governments, can affect political and social stability and the regulatory framework and, therefore, the interests of investors, companies and economic sectors. This conception, which globalisation also leads to call "geopolitical risk", is only a part - in fact, the minor part - of Nigel Gould-Davies' approach, who by putting the adjective "global" in the degree scroll of his book is referring to a conceptually more general political risk, merged with fields such as corporate reputation, public affairs and business diplomacy.

The author claims that the relationship with the environment is essential for a business and calls for a company's management to always have someone manager of engagement (which we could translate as involvement, commitment, participation or partnership): an engager who has the same level of authority as the engineer who knows how to manufacture the product and the salesperson who knows how to monetise it; someone specialised in "persuading" external actors - governments and civil society groups - of the company's goodness, creating "alignments" that are beneficial for business. Engagement at both the national and international level, if the activity or interests go beyond one's own borders, giving rise to "corporate diplomacy", as the current "increase in political risks means that a company needs a foreign policy".

Gould-Davies sees these more political issues not as an "impertinent intrusion" into markets, but as something endogenous to them. So the business, in addition to attending to production and marketing issues, must also pay equal attention to a third dimension: engagement with political and social actors to avoid or overcome risks that it faces in that external sphere. This is "a third activity and a third role to carry it out: a new political piece in the mechanism of value creation".

The author emphasises management on the present and the very short term future deadline, and downplays the importance of short and medium term prospective analysis deadline which has been the preserve of political risk analysts. He complains that the latter have paid "too much attention to prediction, with its frequent disappointments, and too little to engagement"; " engagement, on the other hand, requires relatively little prediction beyond the short deadline". "There is a lot of unbalanced political risk activity, producing a lot of analysis and prediction, but much less guidance on what to do".

Moreover, unlike the usual political risk analysis, which is more focused on the actions of states or governments, the concept the author uses extends very specifically to the pressures that can arise from civil society. "The new political risks emerge from non-state social forces: consumers, investors, public opinion, civil society, local communities and the media. They do not seek to challenge ownership or rights to use productive assets. They do not seek to destroy, take or block. Their focus is narrower: they usually seek to regulate the terms on which production and trade take place (...) Their motive is usually an ethical commitment to justice and equity. Their goal is to mitigate the wider adverse impacts of corporate activity on others; they are selfless rather than self-serving".

Gould-Davies notes that while previously the norm was government threats in development or emerging countries with less stable societies and unconsolidated rule of law, today pressures on business are increasing in developed nations. "The likelihood of major conflict and de-globalisation is increasing, but more importantly, its impact is shifting towards the developed world," he writes. Moreover, the fact that there is less and less social peace in Western countries is an increasingly disturbing element: "Sustained civil violence in a highly developed country is no longer a black swan, but a grey swan: improbable but conceivable; possible to define, but impossible to predict".

By focusing on management in the present and characterising the activity as engagement, which is in itself very communication-centred, Gould-Davis stretches the classical concept of political risk, which has been more oriented towards analysis and foresight, too far. In doing so, he treads on activities that are becoming widely known development for their own sake, such as corporate communication and reputation or influencing regulatory issues through lobbying or public affairs management functions.

[Marko Papic, Geopolitical Alpha. An Investment Framework for Predicting the Future (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2021), 286 pages].

review / Emili J. Blasco

"In the post-Trump and post-Brexit era, geopolitics is all that counts," says Marko Papic in Geopolitical Alpha, a book on political risk whose purpose aims to provide a method or framework from work for those involved in foresight analysis. consultant in investment funds, Papic condenses here his experience in a profession that has gained attention in recent years due to growing national and international political instability. development Whereas risk factors used to be concentrated in emerging countries, they are now also present in the advanced world.

With the book's degree scroll , Papic designates a process of analysis in which geopolitics proper, in its most geographically related sense, is only one part of the considerations to be taken into account, as the author argues that political and then economic (and financial) determinants matter first. For the whole of the analysis and the estimates it gives rise to, Papic uses the qualifier "alpha geopolitics" (or "alpha geopolitics"), as referring to a plus or reinforced geopolitics: one that takes into account political or macroeconomic constraints in addition to traditional geopolitical imperatives.

With the book's degree scroll , Papic designates a process of analysis in which geopolitics proper, in its most geographically related sense, is only one part of the considerations to be taken into account, as the author argues that political and then economic (and financial) determinants matter first. For the whole of the analysis and the estimates it gives rise to, Papic uses the qualifier "alpha geopolitics" (or "alpha geopolitics"), as referring to a plus or reinforced geopolitics: one that takes into account political or macroeconomic constraints in addition to traditional geopolitical imperatives.

At bottom it is a nominalist question, in a collateral battle in which the author unnecessarily entangles himself. It is arguably a settling of scores with his former employer, the George Friedman-led Stratfor, whom Papic praises in his pages, but who he seems to covertly criticise for basing much of his foresight on the geography of nations. To suggest that, however, is to make a caricature of Friedman's solid analysis. In any case, Papic has certainly reinforced his training with programs of study financials and makes useful and interesting use of them.

The central idea of the book, leaving aside this anecdotal rivalry, is that in order to determine what governments will do, one should look not at their stated intentions, but at what constrains them and compels them to act in certain ways. "Investors (and anyone interested in political forecasting) should focus on material constraints, not politicians' preferences," says Papic, adding a phrase that he repeats, in italics, in several chapters: "Preferences are optional and subject to constraints, while constraints are neither optional nor subject to preferences.

These material constraints, according to the order of importance established by Papic, are political conditioning factors (the majority available, the opinion of the average voter, the level of popularity of the government or the president, the time in power or the national and international context, among other factors), macroeconomic and financial constraints (budgetary room for manoeuvre, levels of deficit, inflation and debt, value of bonds and currency....) and geopolitical ones (the imperatives that, derived initially from geography - the particular place that countries occupy on the world stage - mark the foreign policy of nations). To that list, add constitutional and legal issues, but only to be taken into account if the aforementioned factors do not pose any constraint, for it is well known that politicians have little trouble circumnavigating the law.

The author, who presents all this as a method or framework of work, considers that the fact that there may be irrational politicians who entrance do not submit to objective material constraints does not derail the approach, since this status is eventually overcome because "there is no irrationality that can alter reality". However, he admits as a possible objection that, just as the opinion of the average voter conditions the actions of the politician, there may be a "hysterical society" that conditions the politician and is not itself affected in the short term deadline by objective constraints that make it bend to reality. "The time it takes for a whole society to return to sanity is an unknown and impossible prognosis," he acknowledges.

Papic proposes a reasonable process of analysis, broadly followed by other analysts, so there is no need for an initial, somewhat smug boast about his personal prospective skills, which are indispensable for investors. Nevertheless, the book has the merit of a systematised and rigorous exhibition .

The text is punctuated with specific cases, the analysis of which is not only well documented but also conveniently illustrated with tables of B interest. Among them is one that presents the evolution of pro-euro opinion in Germany and the growing Europhile position of the average German voter, without which Merkel would not have reached the previously unthinkable point of accepting the mutualisation of EU debt. Or those that note how England, France and Russia's trade with Germany increased before the First World War, or that of the United States with Japan before the Second World War, exemplifying that rivalry between nations does not normally affect their commercial transactions.

Other interesting aspects of the piece include his warning that "the class average will force China out of geopolitical excitement", because international instability and risk endangers Chinese economic progress, and "keeping its class average happy takes precedence over dominance over the world". "My constraint-based framework suggests that Beijing is much more constrained than US policymakers seem to think (...) If the US pushes too hard on trade and Economics, it will threaten the prime directive for China: escape the middle-income trap. And that is when Beijing would respond with aggression," says Papic.

Regarding the EU, the author sees no risks for European integration in the next decade. "The geopolitical imperative is clear: integrate or perish into irrelevance. Europe is not integrating because of some misplaced utopian fantasy. Its sovereign states are integrating out of weakness and fear. Unions out of weakness are often more sustainable in the long run deadline. After all, the thirteen original US colonies integrated out of fear that the UK might eventually invade again.

Another suggestive contribution is to label as the "Buenos Aires Consensus" the new economic policy that the world seems to be moving towards, away from the Washington Consensus that has governed international economic standards since the 1980s. Papic suggests that we are exchanging the era of "laissez faire" for one of a certain economic dirigisme.

[Daniel Méndez Morán, 136. China's plan in Latin America (2018), 410 pages].

review / Jimena Puga

By means of a first-person on-the-ground research and the testimony staff of Chinese and Latin Americans, who give the story the character of a documented report, Daniel Méndez summarises in detail the mark that the growing Asian superpower is leaving in the region. This gives the reader an insight into the relations between the two cultures from an economic and, above all, political point of view. The figure of degree scroll -136- is the issue that, according to the author, Beijing assigns to its plan for Latin America, in its planning of different sectoral and geographical expansion programmes around the world.

The book begins by briefly reflecting on China's rapid growth since the death of Mao Zedong and thanks to Deng Xiaoping's growth and opening-up policies between 1980 and 2000. This resurgence has not only been reflected in China's Economics but also in society. The new generations of Chinese professionals are better educated training and more fluent in foreign languages than their elders, and therefore better prepared for International Office. However, Liu Rutao, Economic and Commercial Counsellor at the Chinese Embassy in Chile explains to the author that "the history of China's going abroad is only fifteen years old, so neither the government nor the companies have a very mature thinking on how to act abroad, so we all need to study".

However, the country's short experience in the international arena is not an obstacle since, as the book shows, China has a very effective shortcut to accelerate this learning process: money. In fact, the goal of many of the most important Chinese investments in Latin America is not only access to natural resources, but also to human capital and, above all, to knowledge. Thanks to their huge financial resources, Chinese companies are acquiring companies with experience and contacts in the Americas, hiring the best professionals in each country and buying brands and technologies. "This phase is very difficult. Chinese companies are going to pay to learn. But everything is learned by paying," diplomat Chen Duqing, China's ambassador to Brazil between 2006 and 2009, explained to Méndez.

After this overview, the book moves on to China's relationship with different Latin American partners. In the case of Mexico, there is a struggle against the famous made in China. The empire at the centre went to Mexico 40 years ago to study the maquiladora programme; when they returned, Méndez explains, they said: "Mexico is doing that for the United States, we are going to do it for the world". And so, a few years later, China designed and improved the strategy. There is little doubt that made in China has won the day over Mexican maquiladoras, and it is all these decades of skill and frustration that explain the complex political relations between the two countries. This is what the people interviewed by the author testify to. To Jorge Guajardo, this model reminds him of the colonial order imposed by Spain and continued by the United Kingdom: "I sometimes said to the Chinese: 'Gentlemen, you cannot see America: Gentlemen, you cannot see Latin America as anything other than a place where you go for natural resources and in return you send manufactured goods. We were already a colony. And we didn't like it, it didn't work. And we chose to stop being one. You don't want to repeat that model".

The result of these new tensions is that neither country has achieved what it was looking for. Mexico has barely increased its exports to China and the Asian giant has barely increased its investments in the Latin American country. In 2017 there were only 30 Chinese companies installed in Mexico, a very small number compared to the 200 in Peru. Other diplomats on the continent recognise that in any international meeting where both countries are present, the Latin American country is always the most reluctant to accept Beijing's proposals. For China, Mexican 'resistance' is perhaps its biggest diplomatic stumbling block in the region: the best example that its rise has not benefited all countries in the South.

Méndez says that, unlike Mexico, Peru's mining strategy has found an ideal partner on the other side of the Pacific. In need of minerals to feed its industry and build new cities, China's huge demand has pulled strongly on the Peruvian Economics . Between 2004 and 2017, trade between the two countries increased tenfold and the Asian giant became Peru's first commercial partner . China is no longer only important for its demand for copper, lead and zinc, but also for its investment flows and its capacity to implement mining projects. These financial conditions, which are very difficult to obtain from private banks, are often the comparative advantage that allows Chinese state-owned companies to beat their Western competitors.

What does this mean for Latin America, and should Latin American countries be concerned about this political and economic strategy that invests massively in their natural resources through state-owned companies? As the book points out, many diplomats think it is necessary to be vigilant. Unlike private companies, whose primary goal aim is to make profits and submit dividends to their shareholders, Chinese companies are ultimately written request controlled by politicians who may have another diary. In this sense, the expansion of so many state-owned companies in natural resources can also become a weapon of pressure and influence.

If a Latin American leader, for example, decides to meet with the Dalai Lama or opposes a diplomatic initiative led by Beijing, the Asian giant could use its state-owned companies in retaliation, warns Méndez. In the same way that if the Peruvian government wanted to cancel some project chimo for labour or environmental infractions, Beijing could threaten to deny approval of phytosanitary protocols or delay other investments. Moreover, China is increasingly aware that its image, its capacity for persuasion and its cultural attractiveness (soft power) are vital to expand its political and economic project .

On the other hand, further south in the region, Uruguay has become the perfect laboratory for China. Uruguayan factories are prepared for short production runs of a few thousand cars, the country has a specialised workforce and the good infrastructure means that in a very short time it is possible to set up plants in Brazil or Argentina. It should be borne in mind that Chinese companies are still little known in Latin America and do not have many financial resources, and in Uruguay they can test the market.

As for Brazil, Méndez speaks especially of the diplomacy of satellites. Satellites are not only useful for bringing television to homes and for using GPS on mobile phones, but also for their military capabilities and the political prestige they imply. Brazil has collaborated with other countries such as Argentina and the United States, but political and economic tensions almost always limit space cooperation. Paradoxically, in the case of China, distance seems to be a blessing as there are no geopolitical problems between the two: sometimes it is more difficult to work with your neighbours than with people who are far away. For Beijing, space missions serve to enhance all dimensions of its power: it increases its military capabilities and contributes to its space industry and competitiveness in an economic sector with a bright future. And finally, it also serves as a public relations campaign in the world. However, the technological and economic differences are becoming so apparent that even China is outgrowing the South American giant.

From a geostrategic point of view, Méndez does not want to miss the construction of a Chinese space station on a 200-hectare plot of land in the Argentinean province of Neuquén, which has an initial investment of 50 million dollars and is part of China's moon exploration programme. Moreover, Argentina is the only country in which the presence of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China is so popular in society. B . This Chinese bank has managed to offer the same services as any other banking institution in Argentina.

Finally, Chile is one of the countries with which Beijing has the best relations, but why does China not invest in Chile? The answer is simple. Investment processes in Chile are clear, transparent and equal for all countries. There are no exceptions and investors have to follow complex legal regulations to the letter. The business culture is different, and the Chinese don't like the idea of needing lawyers and 20,000 permits for everything. They like to pay bribes, and in Chile corruption provokes a lot of indignation.

Throughout this country-by-country analysis, the author has made one thing clear: China has a plan. Or at least, it has been able to bet for decades on the training of officials with the goal of designing a strategy in Latin America. This capacity for planning and these long-term objectives deadline have helped the Asian giant to advance its position in recent years and leave a deep mark on many countries in the American continent. And what does the plan consist of? It is clear that China's goal issue one is economic. It has managed to successfully "sneak" into the three major trade blocs that include Latin American countries: NAFTA, the Pacific Alliance and Mercosur.

But Economics per se is not the only thing that drives China. To achieve its economic goals, Beijing also needs to build political relations and allies that can defend its diplomatic positions. Its defence of non-interference in internal affairs and a multipolar world demands in return the silence of Latin American countries on human rights violations in their country and respect, for example, for the one-China policy. The Asian giant wants to expand all its strengths and is not willing to give up any of them.

In conclusion, whether or not China has a strategy for Latin America, Latin America does not have a strategy for China. And China is not an NGO; if recent history shows anything, it is that each country seeks to defend its own selfish national interests at the International Office level. China has its diary and is pursuing it. Perhaps the time has come for Latin America to have its own.

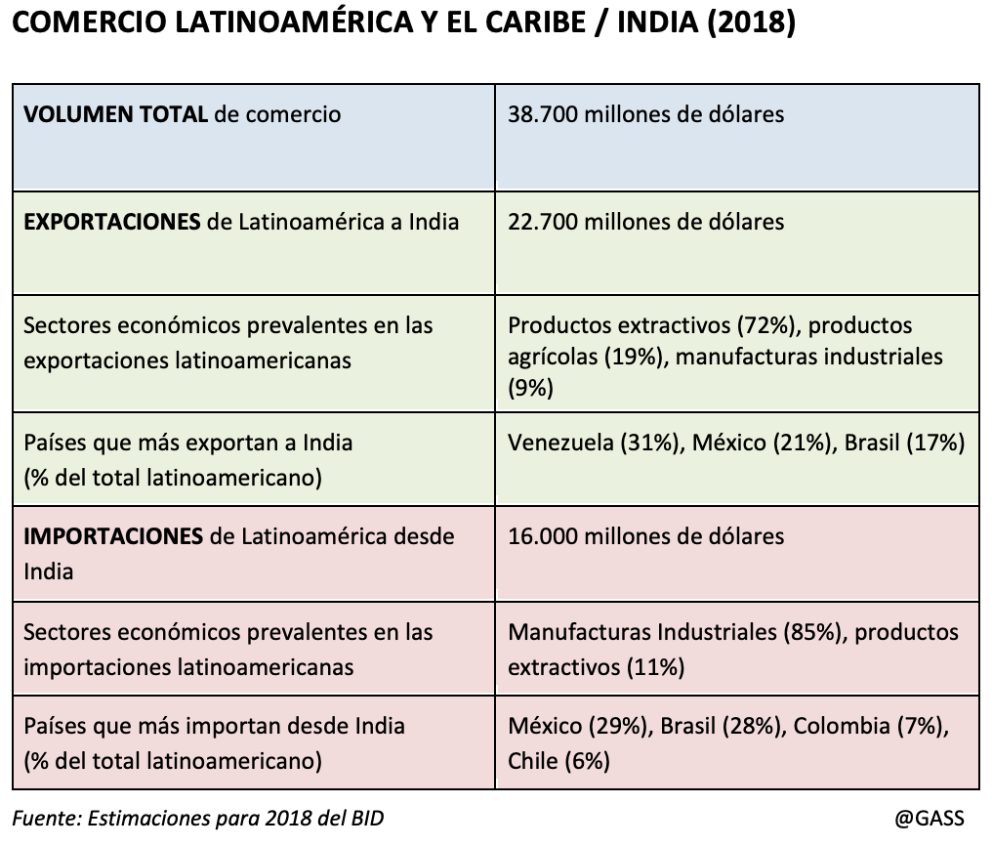

India's trade with the region has increased twenty-fold since 2000, but is only 15% of the trade flow with China.

China's rapid trade, credit and investment spillover into Latin America in the first decade of this century suggested that India, if it intended to follow in the footsteps of its continental rival, could perhaps stage a similar landing in the second decade. This has not happened. India has certainly increased its economic relationship with the region, but it is a far cry from that developed by China. Even Latin American countries' trade flows are greater with Japan and South Korea, although it is foreseeable that in a few years they will be surpassed by those with India given its potential. In an international context of confrontation between the US and China, India emerges as a non-confrontational option, specialising in IT services that are so necessary in a world that has discovered the difficulty of mobility for Covid-19.

article / Gabriela Pajuelo

India has historically paid little attention to Latin America and the Caribbean; the same had been true of China, apart from episodes of migration from both countries. development But China's emergence as a major power and its landing in the region prompted the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to ask in a 2009 report whether, after the Chinese push, India was going to be "the next big thing" for Latin America. Even if India's figures were to lag behind China's, could India become an actor core topic in the region?

Latin American countries' relationship with New Delhi has certainly grown. Even Brazil has developed a special link with India thanks to the BRICS club, as evidenced by Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro's visit in January 2020 to his counterpart Narendra Modi. In the last two decades, India's trade with the region has increased twenty-fold, from $2 billion in 2000 to almost $40 billion in 2018, as a new IDB report found last year.

This volume, however, falls far short of the trade flow with China, of which it constitutes only 15 per cent, because if Indian interests in Latin America have increased, Chinese interests have continued to do so to a greater extent. Investment from both countries in the region is even more disproportionate: between 2008 and 2018, India's investment was $704 million, compared to China's $160 billion.

Even India's trade growth is less regionally intertwined than global figures might suggest. Of the total $38.7 billion of transactions in 2018, $22.7 billion were Latin American exports and $16 billion were imports of Indian products. Indian purchases have already surpassed imports from Latin America by Japan ($21 billion) and South Korea ($17 billion), but this is largely due to the purchase of oil from Venezuela. Adding the two directions of flow, the region's trade with Japan and Korea is still larger (around $50 billion in both cases), but the potential for growth in the trade relationship with India is clearly greater.

There is interest not only from American countries, but also from India. "Latin America has a young and skilled workforce, work , and is rich in natural and agricultural resource reserves," said David Rasquinha, director general manager of the Export-Import Bank of India.

Last decade

The two IDB reports cited above are a good reflection of the leap in relations between the two markets in the last decade. In the 2009 report, under degree scroll 'India: Opportunities and Challenges for Latin America', the Inter-American institution presented the opportunities offered by contacts with India. Although it was committed to increasing them, the IDB was uncertain about the evolution of a power that for a long time had opted for autarky, as Mexico and Brazil had done in the past; however, it seemed clear that the Indian government had finally taken a more conciliatory attitude towards the opening up of its Economics.

Ten years later, the report graduate "The Bridge between Latin America and India: Policies for Deepening Economic Cooperation" delved into the opportunities for cooperation between the two actors and noted the importance of strengthening ties to favour the growing internationalization of the Latin American region, through the diversification of trade partners and access to global production chains. In the context of the Asian Century, the flow of exchange trade and direct investment had increased exponentially from previous levels, result largely due to the demand for Latin American raw materials, something that is often criticised as not fostering the region's industry.

The new relationship with India presents an opportunity to correct some of the trends in interaction with China, which has focused on investment by state-owned companies and loans from Chinese state-owned banks. In the relationship with India, there is greater participation of Asian private initiative and a commitment to new economic sectors, as well as the hiring of indigenous staff , including at the management and management levels.

agreement According to General Manager of the IDB's Integration and Trade Sector, Fabrizio Opertti, "the development of an effective institutional framework and business networks" is crucial. The IDB suggests possible governmental measures such as increasing the coverage of trade and investment agreements, the development of proactive and targeted trade promotion activities, boosting investments in infrastructure, promoting reforms in the logistics sector, among others.

Post-Covid context

The questioning of global production chains and, ultimately written request, of globalisation itself because of the Covid-19 pandemic, is not conducive to international trade. Moreover, the economic crisis of 2020 may have a long-lasting effect on Latin America. But it is precisely in this global framework that the relationship with India could be particularly interesting for the region.

Within Asia, in a context of polarisation over the geopolitical interests of China and the United States, India emerges as a partner core topic , one might even say neutral; something that New Delhi could use strategically in its approach to different areas of the world and in particular to Latin America.

Although "India does not have pockets as deep as the Chinese", as Deepak Bhojwani, founder of the consultancy firm Latindia[1], says in relation to the enormous public funding that Beijing manages, India could be the origin of interesting technological projects, given the variety of IT and telecommunications companies and experts it has. Thus, Latin America could be the target of the "technology foreign policy" of a country that, according to agreement with its Ministry of Electronics and IT, has the ambition of growing its digital Economics to "one trillion dollars by 2025". New Delhi will focus its efforts on influencing this economic sector through NEST (New, Emerging and Strategic Technologies), promoting a unified Indian message on emerging technologies, such as governance of data and artificial intelligence, among others. The pandemic has highlighted Latin America's need for more and better connectivity.

There are two prospects for the expansion of India's influence on the continent. One is the obvious path of strengthening its existing alliance with Brazil, within the BRICS, whose pro tempore presidency India holds this year. That should lead to more diversified ties with Brazil, the region's largest market, especially in science and technology cooperation, in the fields of IT, pharmaceuticals and agribusiness. "Both governments committed to expand bilateral trade to 15 billion dollars by 2022. Despite the difficulties brought by the pandemic, we are pursuing this ambitious goal", says André Aranha Corrêa do Lago, Brazil's current ambassador to India.

On the other hand, a greater effort could be made in bilateral diplomacy, insisting on pre-existing ties with Mexico, Peru and Chile. The latter country and India are negotiating a preferential trade agreement and the Bilateral Investment Protection Treaty signature . A rapprochement with Central America, which still lacks Indian diplomatic missions, may also be of interest. These are necessary steps if, closely following in China's footsteps, India wants to be the "next big thing" for Latin America.

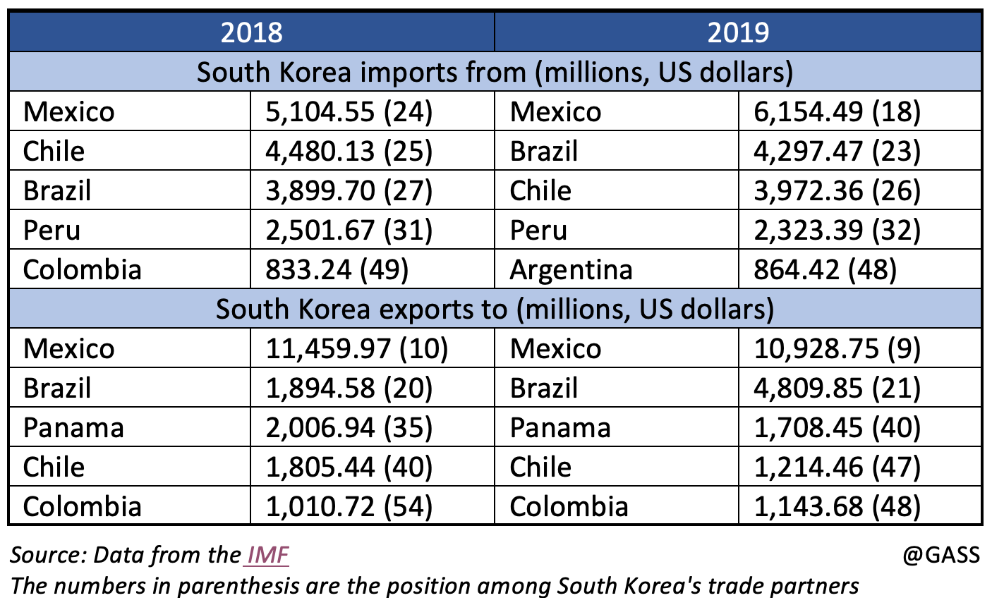

The increase in South Korean trade with Latin American countries has allowed the Republic of Korea to reach Japan's exchange figures with the region.

Throughout 2018, South Korea's trade with Latin America exceeded USD 50 billion, putting itself at the same level of trade maintained by Japan and even for a few months becoming the second Asian partner in the region after China, which had flows worth USD 300 billion (half of the US trade with its continental neighbours). South Korea and Japan are ahead of India's trade with Latin America (USD 40 billion).

ARTICLE / Jimena Villacorta

Latin America is a region highly attractive to foreign markets because of its immense natural resources which include minerals, oil, natural gas, and renewable energy not to mention its agricultural and forest resources. It is well known that for a long time China has had its eye in the region, yet South Korea has also been for a while interested in establishing economic relations with Latin American countries despite the spread of new protectionism. Besides, Asia's fourth largest economy has been driving the expansion of its free trade network to alleviate its heavy dependence on China and the United States, which together account for approximately 40% of its exports.

The Republic of Korea has already strong ties with Mexico, but Hong Nam-ki, the South Korean Economy and Finance Minister, has announced that his country seeks to increase bilateral trade between the regions as it is highly beneficial for both. "I am confident that South Korea's economic cooperation with Latin America will continue to persist, though external conditions are getting worse due to the spread of new protectionism", he said. While Korea's main trade with the region consists of agricultural products and manufacturing goods, other services such as ecommerce, health care or artificial intelligence would be favourable for Latin American economies. South Korean investment has significantly grown during the past decades, from USD 620 million in 2003, to USD 8.14 billion in 2018. Also, their trade volume grew from USD 13.4 billion to 51.5 billion between the same years.

Apart from having strong ties with Mexico, South Korea signed a Free Trade Agreement with the Central American countries and negotiates another FTA with the Mercosur block. South Korea would like to join efforts with other Latin American countries in order to breathe life into the Trans-Pacific Partnership, bringing the US again into the negotiations after a change of administration in Washington.

Mexico

Mexico and South Korea's exports and imports have increased in recent years. Also, between 1999 and 2015, the Asian country's investments in Mexico reached USD 3 billion. The growth is the result of tied partnerships between both nations. Both have signed an Agreement for the Promotion and Reciprocal Protection of Investments, an Agreement to Avoid Income Tax Evasion and Double Taxation and other sectoral accords on economic cooperation. Both economies are competitive, yet complementary. They are both members of the G20, the OECD and other organisations. Moreover, both countries have high levels of industrialization and strong foreign trade, key of their economic activity. In terms of direct investment from South Korea in Mexico, between 1999 and June 2019, Mexico received USD 6.5 billion from Korea. There are more than 2,000 companies in Mexico with South Korean investment in their capital stock, among which Samsung, LG, KORES, KEPCO, KOGAS, Posco, Hyundai and KIA stand out. South Korea is the 12th source of investment for Mexico worldwide and the second in Asia, after Japan. Also, two Mexican multinationals operate in South Korea, group Promax and KidZania. Mexico's main exports to South Korea are petrol-based products, minerals, seafood and alcohol, while South Korea's main exports to Mexico are electronic equipment like cellphones and car parts.

Mercosur

Mercosur is South America's largest trading economic bloc, integrated by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. With a GDP exceeding USD 2 trillion, it is one of the major suppliers of raw materials and agricultural and livestock products. South Korea and Mercosur launched trade negotiations on May 2018, in Seoul. Actually, the Southern Common Market and the Republic of Korea have been willing to establish a free trade agreement (FTA) since 2005. These negotiations have taken a long time due to Mercosur's protectionism, so the Asian country has agreed on a phased manner agreement to reach a long-term economic cooperation with the bloc. The first round of negotiations finally took place in Montevideo, the Uruguayan capital, in September 2018. Early this year, they met again in Seoul to review the status of the negotiations for signing the Mercosur-Korea trade agreement. This agreement covers on the exchange of products and services and investments, providing South Korean firms faster access to the Latin American market. The Asian tiger main exports to South America are industrial goods like auto parts, mobile devices and chips, while its imports consist of mineral resources, agricultural products, and raw materials like iron ore.

Among Mercosur countries, South Korea has already strong ties with Brazil. Trade between both reached USD 1.70 billion in 2019. Also, South Korean direct investments totaled USD 3.69 billion that same year. With the conclusion of the trade agreement with the South American block, Korean products exported to Brazil would benefit from tariff eliminations, as would Korean position trucks, and other products going to Argentina. It would also be the first Asian country to have established a trade agreement with Mercosur.

Central America

South Korea is the first Asian-Pacific country to have signed a FTA with Central American countries (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama). According to Kim Yong-beom, South Korean Deputy Minister of Economy and Finance, bilateral cooperation will benefit both regions as state regulatory powers won't create unnecessary barriers to commercial exchange between both. "The FTA will help South Korean companies have a competitive edge in the Central American region and we can establish a bridgehead to go over to the North and South American countries through their FTA networks", said Kim Hak-do, Deputy Trade Minister, when the agreement was reached in November 2016. Also, both economic structures will be complimented by each other by encouraging the exchange between firms from both regions. They signed the FTA on February 21st, 2018, after eighth rounds of negotiations from June 2015 to November 2016 that took place in Seoul, San Salvador, Tegucigalpa and Managua. Costa Rica also signed a memorandum of understanding with South Korea to boost trade cooperation and investment. This partnership will create new opportunities for both regions. South Korean consumers will have access to high-quality Central American products like grown coffee, agricultural products, fruits like bananas, and watermelons, at better prices and free of tariffs and duties. Additionally, Central American countries will have access to goods like vehicle parts, medicines and high-tech with the same advantages. Besides unnecessary barriers to trade, the FTA will promote fair marketing, ease the exchange of goods and services, to encourage the exchange businesses to invest in Central America and vice versa. Moreover, having recently joined the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) as an extra-regional member, has reinforced the development of partner-economic projects around the region.

Opportunity

The Republic of Korea faces challenges related to the scarcity of natural resources, there are others, such as slower growth in recent decades, heavy dependence on exports, competitors like China, an aging population, large productivity disparities between the manufacturing and service sectors, and a widening income gap. Inasmuch, trade between Latin America and the Caribbean and the Republic of Korea, though still modest, has been growing stronger in recent years. Also, The Republic of Korea has become an important source of foreign direct investment for the region. The presence of Korean companies in a broad range of industries in the region offers innumerable opportunities to transfer knowledge and technology and to create links with local suppliers. FTAs definitely improve the conditions of access to the Korean market for the region's exports, especially in the most protected sectors, such as agriculture and agro-industry. The main challenge for the region in terms of its trade with North Korea remains export diversification. The region must simultaneously advance on several other fronts that are negatively affecting its global competitiveness. It is imperative to close the gaps in infrastructure, education and labor training.