Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Trials .

![Tourist town in Gjirokastër district, southern Albania [Pixabay]. Tourist town in Gjirokastër district, southern Albania [Pixabay].](/documents/10174/16849987/albania-ue-blog.jpg)

Tourist population in Gjirokastër district, southern Albania [Pixabay].

ESSAY / Jan Gallemí

On 24 November 2019, the French government of Enmanuel Macron led the veto, together with other states such as Denmark and the Netherlands, of the accession of the Balkan nations of Albania and North Macedonia to the European Union. According to the president of the French Fifth Republic, this is due to the fact that the largest issue of economic refugees entering France are from the Balkans, specifically from the aforementioned Albania. The latter country applied to join the European Union on 28 April 2009, and on 24 June 2014 it was unanimously agreed by the 28 EU countries to grant Albania the status of a country candidate for accession. The reasons for this rejection are mainly economic and financial.[1]. There is also a slight concern about the diversity that exists in the ethnographic structure of the country and the conflicts that this could cause in the future, not only within the country itself but also in its relationship with its neighbours, especially with the Kosovo issue and relations with Greece and North Macedonia.[2]. However, another aspect that has also been explored is the fact that Albania's accession would mean the EU membership of the first state in which the religion with the largest number of followers is Islamic, specifically the Sunni branch, issue . This essay will proceed to analyse the impact of this aspect and observe how, or to what extent, Albanian values, mainly because they are primarily Islamic in religion, may combine or diverge from those on which the common European project is based.

Evolution of Islam in Albania

One has to go back in history to consider the reasons why a European country like Albania has developed a social structure in which the religion most professed by part of the population is Sunni. Because of the geographical region in which it is located, it would theoretically be more common to think that Albania would have a higher percentage of Orthodox than Sunni population.[3]. The same is true for Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This region was originally largely Orthodox Christian in the south (like most Balkan states today) due to the fact that it was one of the many territories that made up the Byzantine Empire until the 13th century, when the nation gained its independence. However, the reason why Islam is so present in Albania, unlike its neighbouring states, is that it was more religiously influenced by the Ottoman Empire, the successor to the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire fell in 1453 and its territories were occupied by the Ottomans, a Turkish people established at that time on the Anatolian peninsula. According to historians such as Vickers, it was between the 17th and 18th centuries that a large part of the Albanian population converted to Islam.[4]The reason for this, as John L. Esposito points out, was that for the Albanian population, changing their religion meant getting rid of the higher taxes that Christians had to pay in the Ottoman Empire.[5].

Religion in Albania has since been shaped by events. As far as we know from programs of study such as those of Gawrych in the 19th century, Albanian society was then divided mainly into three groups: Catholics, Orthodox and Sunnis (the latter represented 70% of the population). The same century saw the birth of many of the well-known European nationalisms and the beginning of the so-called Eastern crisis in the Balkans. During this period many Balkan peoples revolted against the Ottomans, but the Albanians, identifying with the Ottomans through their religion, initially remained loyal to the Sultan.[6]. Because of this support, Muslim Albanians began to be pejoratively referred to as "Turks".[7]. This caused Albanian nationalism to distance itself from the emerging Ottoman pan-Islamism of Sultan Abdualhmid II. This gave rise, according to Endresen, to an Albanian national revival called Rilindja, which sought the support of Western European powers.[8].

The Balkan independence movements that emerged in the 19th century generally reinforced Christian as opposed to Muslim sentiment, but in Albania this was not the case; as Stoppel points out, both Albanian Christians and Muslims cooperated in a common national goal .[9]. This encouraged the coexistence of both beliefs (already present in earlier times) and allowed the differentiation of this movement from Hellenism.[10]. It is worth noting that at that time in Albania Muslims and Christians were peculiarly distributed territorially: in the north there were more Catholic Christians who were not so influenced by the Ottoman Empire, and in the south Orthodox also predominated because of the border with Greece. On 28 November 1912 the Albanians, led by Ismail Qemali, finally declared independence.

The international recognition of Albania by the Treaty of London meant the imposition of a Christian monarchy, which led to the outrage of Muslim Albanians, estimated at 80% of the population, and sparked the so-called Islamic revolt. The revolt was led by Essad Pasha Toptani, who declared himself the "saviour of Albania and Islam" and surrounded himself with disgruntled clerics. However, during the period of World War I, Albanian nationalists soon realised that religious differences could lead to the fracturing of the country itself and decided to break ties with the Muslim world in order to have "a common Albania", which led to Albania declaring itself a country without an official religion; this allowed for a government with representation from the four main religious faiths: Sunni, Bektashi, Catholic and Orthodox, training . Albanian secularist elites planned a reform of Islam that was more in line with Albania's traditions in order to further differentiate the country from Turkey, and religious institutions were nationalised. From 1923 onwards, the Albanian National congress eventually implemented the changes from a perspective very similar to that of Western liberalism. The most important reforms were the abolition of the hijab and the outlawing of polygamy, and a different form of prayer was implemented to replace the Salat ritual. But the biggest change was the replacement of Sharia law with Western-style laws.

During World War II Albania was occupied by fascist Italy and in 1944 a communist regime was imposed under the leadership of Enver Hoxha. This communist regime saw the various religious beliefs in the country as a danger to the security of the authoritarian government, and therefore declared Albania the first officially atheist state and proposed the persecution of various religious practices. Thus repressive laws were imposed that prevented people from professing the Catholic or Orthodox faiths, and forbade Muslims from reading or possessing the Koran. In 1967 the government demolished as many as 2,169 religious buildings and converted the rest into public buildings. Of 1,127 buildings that had any connection to Islam at the time, only about 50 remain today, and in very poor condition.[11]. It is believed that the impact of this persecution subject was reflected in the increase of non-believers within the Albanian population. Between 1991 and 1992 a series of protests brought the regime to an end. In this new democratic Albania, Islam was once again the predominant religion, but the preference was to maintain the non-denominational nature of the state in order to ensure harmony between different faiths.

Influences from the international arena

Taking into account this reality of Albania as a country with a majority Islamic population, we turn to the impact of its accession to the EU and the extent to which the values of the two contradict each other.

To begin with, if all this is analysed from a perspective based on the theory of "constructivism", such as that of Helen Bull's proposal , it can be seen how Albania from the beginning of its history has been a territory whose social structure has been strongly influenced by the interaction of different international actors. During the years when it was part of the Byzantine Empire, it largely absorbed Orthodox values; when it was occupied by the Ottomans, most of its population adopted the Islamic religion. Similarly, during the de-Ottomanisation of the Balkans, the country adopted currents of political thought such as liberalism due to the influence of Western European powers. This led to a desire to create a constitutionalist and parliamentary government whose vision of politics was not based on any religious morality.[12]. It can also be seen that the communist regime was imposed in a context common to that of the other Eastern European states. At the same time, it also returned to a democratic path after the collapse of the USSR, even though Albania had not maintained good relations with the Warsaw Pact since 1961.

Since Albania's EU candidacy, these liberal values have been strengthened again. In particular, Albania is striving to improve its infrastructure and to eradicate corruption and organised crime. So it can be seen that Albanian society is always adapting to being part of a supra-governmental organisation. This is an important aspect because it means that the country is most likely to actively participate in the proposals made by the European Commission, without being driven by domestic social values. However, this in turn gives a point in favour of those MEPs who argued that the veto decision was a historic mistake. For if it does not alienate the EU, Albania could alienate other international actors. According to MEPs themselves, these could be Russia or China.

However, there are two limitations to this assertion. The first is that since 2012 Albania has been a member of NATO, so it is already partly alienated from the West in military terms. But a second aspect is more important, namely that Albania already tried during the Cold War to alienate itself from Russia and China, but found that this had negative effects as it made it a satellite state. On the other hand, and this is where Islamic values come into play, Albania today is a member of Islamic organisations such as the OIC (Organisation of Islamic Cooperation). Rejection by the EU could therefore mean Albania's realignment with other Islamic states, such as the Arabs or Turkey. Turkey's own government, currently led by Erdogan's party, has a neo-Ottomanist nature: it seeks to bring the states that formerly constituted the Ottoman Empire under its influence. Albania is being influenced by this neo-Ottomanism and a European rejection could bring it back into the fold of this conception.[13]. Moreover, by moving closer to Middle Eastern Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia, Albania would run the risk of assimilating the Islamic values of these territories.[14]These are incompatible with those of the EU because they do not comply with many of the articles signed up to in the 1952 Universal Declaration of Rights.

Islam and the European Union

Another aspect would be to ask in what respects do Islamic values contradict those of the EU? The EU generally claims to be against polygamy, homophobia or religious practices that oppose the dignity of the person. This has generated, among other things, a powerful internal discussion as to whether the hijab can be considered as a internship staff that should not be legally prevented. Many feminist groups are against this aspect as they relate it to family patriarchalism.[15]However, other EU groups claim that this is only a fully respectable individual internship staff and that its abolition would be a gesture of an Islamophobic nature. In any case, as mentioned above, Albania abolished both polygamy and the wearing of the hijab in 1923 as not reflecting the values of Islam in Albania.[16]. In this respect, it can be observed that although Albania is a country with an Islamic majority, this Islam is much more influenced by Europeanist currents than by Eastern ones: that is, an Islam adapted to European customs and whose values are currently more similar to those of the neighbouring Balkan states.

Some MEPs, usually from far-right groups such as Ressamblement National or Alternativ für Deutschland, claim that Islamic values will never be compatible with European values because they are expansionist and radical. Dutchman Geert Wilders claims that the Koran "is more anti-Semitic than Mein Kampf".[17]. In other words, they claim that those who profess Islam are incapable of maintaining good relations with other faiths because the Koran itself speaks of waging war against the infidel through Jihad. As an example, they cite the terrorist attacks that the Islamist group DAESH has provoked over the last decade, such as those perpetrated in Paris and Barcelona.[18]. But these groups should be reminded that a sacred text such as the Koran can be interpreted in many ways and that although some Muslim groups believe in this incompatibility of good relations with those who think differently, the majority of Muslims interpret the Koran in a very different way, just as they do the Bible, even if some very specific groups become irrational.

This is clearly the case in Albania, where since its democratisation in 1991 there has been a national project integrating all citizens, regardless of their different beliefs. Rather, throughout its history as an independent country there has been only one period of religious persecution in Albania, and that was due to the repression of communist authoritarianism. One limitation in this respect might be the Islamic revolution that took place in Albania in 1912. But it is worth noting that this revolution, despite its strong Islamic sentiment, served to overthrow a puppet government; no law was enforced after it to impose Islamic values on the rest. So it is worth noting that Albania's political model is very similar to that of Rawls in his book "Political Liberalism", because it configures a state with multiple values (although there is a predominant one), but its laws are not written on the basis of any of them, but on the basis of common values among all of them based on reason.[19]. This model proposed by Rawls is one of the founding instructions of the European Union and Albania would be a state that would exemplify these same values.[20]. This is what the Supreme Pontiff Francis I said at his visit in Tirana in 2014: "Albania demonstrates that peaceful coexistence between citizens belonging to different religions is a path that can be followed in a concrete way and that produces harmony and liberates the best forces and creativity of an entire people, transforming simple coexistence into true partnership and fraternity".[21].

Conclusions

It can be concluded that Albania's values as an Islamic-majority state do not appear to be divergent from those of Western Europe and thus the European Union. Albania is a non-denominational state that respects all religious beliefs and encourages all individuals, regardless of their faith, to participate in the political life of the country (which has much merit given the significant religious diversity that has distinguished Albania throughout its history). Moreover, Islam in Albania is very different from other regions due to the impact of European influence in the region. Not only that, but the country also seems very willing to collaborate on common projects. The only thing that, in terms of values, would make Albania unsuitable for EU membership would be if, just as it has been influenced by the actors that have interacted with it throughout its history, it were to be influenced again by Muslim states with values divergent from European ones. But this is more likely to be the case if the EU were to reject Albania, as it would seek the support of other allies in the international arena.

The implications of the accession of the first Muslim-majority state to the EU would certainly be advantageous, as it would encourage a variety of religious thought within the Union and this could lead to greater understanding between the different faiths within it. There would be the possibility of a greater presence of Sunni MEPs in the European Parliament and it would help to enhance coexistence within other EU states on the basis of what has been done in Albania, such as in France, where 10 per cent of the population is Muslim. It should also be said that Albania's exemplary multi-religious behaviour would seriously weaken Euroscepticism and also help to foster harmony within the Balkan region. As Donald Tusk has argued, the Balkans must be given a European perspective and it is in the EU's best interest that Albania becomes part of it.

[1] Lazaro, Ana; European Parliament adopts resolution against veto on North Macedonia and Albania; euronews. ; last update: 24/10/2019

[2] Sputnik World; The West's attitude to the spectre of 'Greater Albania' worries Moscow; Sputnik World, 22/02/2018. grade Sputnik World: Care should be taken when analysing this source as it is often used as a method of Russian propaganda.

[3] "Third Opinion on Albania adopted on 23 November 2011". Strasbourg. 4 June 2012.

[4] Vickers, Miranda (2011). The Albanians: a modern history. London: IB Tauris.

[5] Esposito, John; Yavuz, M. Hakan (2003). Turkish Islam and the secular state: The Gülen movement. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press

[6] Gawrych, George (2006). The crescent and the eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874-1913. London: IB Tauris.

[7] Karpat, Kemal (2001). The politicization of Islam: reconstructing identity, state, faith, and community in the late Ottoman state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[8] Endresen, Cecilie (2011). "Diverging images of the Ottoman legacy in Albania". Berlin: Lit Verlag. pp. 37-52.

[9] Stoppel, Wolfgang (2001). Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien). Cologne: Universität Köln.

[10] Gawrych, George (2006). The crescent and the eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874-1913. London: IB Tauris.

[11] Nurja, Ermal (2012). "The rise and destruction of Ottoman Architecture in Albania: A brief history focused on the mosques". Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

[12] Albanian Constituition of 1998.

[13] Return to Instability: How migration and great power politics threaten the Western Balkans. European Council on Foreign Relations. 2015.

[14] Bishku, Michael (2013). "Albania and the Middle East.

[15] García Aller, Marta; Feminists against the hijab: "Europe is falling into the Islamist trap with the veil".

[16] Jazexhi, Olsi (2014)."Albania." In Nielsen, Jørgen; Akgönül, Samim; Alibašić, Ahmet; Racius, Egdunas (eds.) Yearbook of Muslims in Europe: Volume 6. Leiden: Brill.

[17] EFE; The Dutch MP who compared the Koran to 'Mein Kampf' does not withdraw his words. La Vanguardia; 04/10/2010

[18] Khader, Bichara; Muslims in Europe, the construction of a "problem"; OpenMind BBVA

[19] Rawls, John; Political Liberalism; Columbia University Press, New York.

[20] Kristeva, Julia; Homo europaeus: is there a European culture; OpenMind BBVA.

[21] Vera, Jarlison; Albania: Pope highlights the partnership between Catholics, Orthodox and Muslims; Acaprensa

![Members of the Blue Helmets in their deployment in Mali [MINUSMA]. Members of the Blue Helmets in their deployment in Mali [MINUSMA].](/documents/10174/16849987/minusma-blog.jpg)

▲ Members of the Blue Helmets in their deployment in Mali [MINUSMA].

ESSAY / Ignacio Yárnoz

INTRODUCTION

It has been 72 years since the first United Nations peacekeeping operation was deployed in Israel/Palestine to supervise the ceasefire agreement between Israel and his Arab neighbours. Since then, more than 70 peacekeeping operations have been deployed by the UN all over the world, though with special attention to the Middle East and Africa. Over these more than 70 years, hundreds of thousands of military personnel from more than 120 countries have participated in UN peacekeeping operations. Nowadays, there are 13 UN peacekeeping operations deployed in the world, seven of which are located in African countries supported by a total of 83,436 thousand troops (around 80 percent of all UN peacekeepers deployed around the world) and thousands of civilians. The largest missions in terms of number of troops and ambitious objectives are those in the Democratic Republic of Congo (20,039 troops), South Sudan (19,360 troops), and Mali (15,162 troops)[1].

Peacekeepers in Africa, as in other regions, are given broad and ambitious mandates by the Security Council which include civilian protection, counterterrorism, and counterinsurgency operations or protection of humanitarian relief aid. However, these objectives must go hand by hand with the core UN peacekeepers principles, which are consent by the belligerent parties, impartiality (not neutrality) and the only use of force in case of self-defence[2].

Although peace operations can be important for maintaining stability and safeguarding democratic transitions, multilateral institutions such as UN face challenges related to country contributions, training, a very hostile environment and relations with host governments. It is often stated that these missions have failed largely because they were deployed in a context of ongoing wars where the belligerents themselves did not want to stop fighting or preying on civilians and yet have to manage to protect many civilians and reduce some of the worst consequences of civil war.

In addition, UN peacekeepers are believed to be deployed in the most recent missions to war zones where not all the main parties have consented. There is also mounting international pressure for peacekeepers to play a more robust role in protecting civilians. Despite the principle of impartiality, UN peacekeepers have been tasked with offensive operations against designated enemy combatants. Contemporary mandates have often blurred the lines separating peacekeeping, stabilization, counterinsurgency, counterterrorism, atrocity prevention, and state-building.

Such features have often been referred to the case of the peacekeeping operation in Mali (MINUSMA) as I will try to sum up in this essay. This mission, ongoing since 2013 is on its seventh year and tensions between the parties have still not ceased due to several reasons I will further explain in this essay. Through a summarized history of the ongoing conflict, an explanation of the current military/police deployment, the engagement of third parties and an assessment on the risks and opportunities of this mission as well as an analysis of its successes and failures I will try to give a complete analysis on what MINUSMA is and its challenges.

Brief history of the conflict in Mali

During the last 8 years, Mali has been immersed in a profound crisis of Governance, partner-economic instability, terrorism and human rights violations. The crisis mentioned stems from several factors I will try to develop in this first part of the analysis. The crisis derives from long-standing structural conditions that Mali has experienced, such as ineffective Governments due to weak State institutions; fragile social cohesion between the different ethnic and religious groups; deep-rooted independent feelings among communities in the north due to marginalization by the central Government and a weak civil society among others. These conditions were far exacerbated by more recent instability, a spread corruption, nepotism and abuse of power by the Government, instability from neighbouring countries and a decreased effective capacity of the national army.

It all began in mid-January 2012 when a Tuareg movement called Mouvement National pour la Libération de l'Azawad (MNLA) and some Islamic armed groups such as Ansar Dine, Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Mouvement pour l'Unicité et le Jihad en Afrique de l'Ouest (MUJAO) initiated a series of attacks against Government forces in the north of the country[3]. Their primary goals for these rebel groups though different could be summarized into declaring the Northern regions of Timbuktu, Kidal and Gao (the three together called Azawad) independent from the Central Government of Mali in Bamako and re-establishing the Islamic Law in these regions. The Tuareg led rebellion was reinforced by the presence of well-equipped and experienced combatants returning from Libya's revolution of 2011 in the wake of the fall of Gadhafi's regime[4].

By March 2012, the Malian Institutions had been overwhelmingly defeated by the rebel groups and the MNLA seemed to almost have de facto taken control of the North of Mali. As a consequence of the ineffectiveness to handle the crisis, on 22 March a series of disaffected soldiers from the units defeated by the armed groups in the north resulted in a military coup d'état led by mid-rank Capt Aamadou Sanogo. Having overthrown President Amadou Toumane Toure, the military board took power, suspended the Constitution and dissolved the Government institutions[5]. The coup accelerated the collapse of the State in the north, allowing MNLA to easily overrun Government forces in the regions of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu and proclaim an independent State of Azawad on 6 April. The Military board promised that the Malian army would defeat the rebels, but the ill-equipped and divided army was no match for the firepower of the rebels.

Immediately after the coup, the International Community condemned this act and lifted sanctions against Mali if the situation wasn't restored. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) appointed the President of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaoré, as the mediator on the crisis and compromised the ECOWAS would help Malian Government to restore order in the Northern region if democracy was brought back[6]. On 6 April, the military board and ECOWAS signed a framework agreement that led to the resignation of Capt Aamadou Sanogo and the appointment of the Speaker of the National Assembly, Dioncounda Traoré, as interim President of Mali on 12 April. On 17 April, Cheick Modibo Diarra was appointed interim Prime Minister and three days later, he announced the formation of a Government of national unity.

However, something happened during the rest of the year 2012 after the Malian government forces had been defeated. Those who were allies one day, became enemies of each other and former co-belligerents Ansar Dine, MOJWA, and the MNLA soon found themselves in a conflict.

Clashes began to escalate especially between the MNLA and the Islamists after a failure to reach a power-sharing treaty between the parties. As a consequence, the MNLA forces soon started to be driven out from the cities of Kidal, Timbuktu and Gao. The MNLA forces lacked as many resources as the Islamist militias and had experienced a loss of recruits who preferred the join the better paid Islamist militias. However, the MNLA stated that it continued to maintain forces and control some rural areas in the region. As of October 2012, the MNLA retained control of the city of Ménaka, with hundreds of people taking refuge in the city from the rule of the Islamists, and the city of Tinzawatene near the Algerian border. Whereas the MLNA only sought the Independence of Azawad, the Islamist militias goal was to impose the sharia law in their controlled cities, which drove opposition from the population.

Foreign intervention

Following the events of 2012, the Malian interim authorities requested United Nations assistance to build the capacities of the Malian transitional authorities regarding several key areas to the stabilization of Mali. Those areas were the reestablishment of democratic elections, political negotiations with the opposing northern militias, a security sector reform, increased governance on the entire country and humanitarian assistance.

The call for assistance came in the form of a UN deployment in mid-January 2013 authorised by Security Council resolution 2085 of 20 December 2012. This resolution gave the UN a mandate with two clear objectives: provide support to (i) the on-going political process and (ii) the security process, including support to the planning, deployment and operations of the African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA)[7].

The newly designated mission was planned to be an African led mission (Africa Union and ECOWAS) and funded through the UN trust fund and the European Union Africa Peace Facility. The mission was mandated several objectives: (i) contribute to the rebuilding of the capacity of the Malian Defence and Security Forces; (ii) support the Malian authorities in recovering the areas in the north; (iii) support the Malian authorities in maintaining security and consolidate State authority; (iv) provide protection to civilians and (iv) support the Malian authorities to create a secure environment for the civilian-led delivery of humanitarian assistance and the voluntary return of internally displaced persons and refugees.

However, the security situation in Mali further deteriorated in early January 2013, when the three main Islamist militias Ansar Dine, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa and Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, advanced southwards. After clashing with the Government forces north of the town of Konna, some 680 kilometres from Bamako, the Malian Army was forced to withdraw. This advance by the Islamist militias raised the alarms in the International arena as they were successfully taking control of key areas and strategic spots in the country and could soon advance to the capital if nothing was done.

The capture of Konna by extremist groups made the Malian transitional authorities to consider requesting once again the assistance of foreign countries, in especial to its ancient colonizer France, who accepted launching a military operation to support the Malian Army. It is also true that France was already keen on intervening as soon as possible due the importance of Sévaré military airport, located 60 km south of Konna, for further operations in the Sahel area.

Operation Serval, as coined by France, was initiated on 11 January with a deployment of a total of 3,000 troops[8] and air support from Mirage 2000 and Rafale squadrons. In addition, the deployment of AFISMA to support the French deployment was fostered. As a result, the French and African military operations alongside the Malian army successfully improved the security situation in northern areas of Mali. By the end of January, State control had been restored in most major northern towns, such as Diabaly, Douentza, Gao, Konna and Timbuktu. Most terrorist and associated forces withdrew northwards into the Adrar des Ifoghas mountains and many of their leaders such as Abdelhamid Abou Zeid were reported eliminated.

Despite taking control back to the government authorities and restoring the territorial integrity of the country, serious security challenges remained. Although the main cities had been taken back, terrorist attacks remained frequent, weapons proliferated in the rural and urban areas, drug smuggling was increasing and other criminal activities were also maintained active, which undermine governance and development in Mali. Therefore, the fight just transitioned from a territorial and conventional war to a guerrilla style warfare much more difficult to neutralise.

United Nations deployment

Following the gradual withdrawal of the French troops from Mali (Operation Serval evolved to Operation Barkhane in the Sahel region), AFISMA took responsibility to secure the stabilization and the implementation of a transitional roadmap which demanded more resources and engagement from more countries. As a consequence, AFISMA mission officially transitioned to be MINUSMA (United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali) by Security Council Resolution 2100 of April 25, 2013[9].

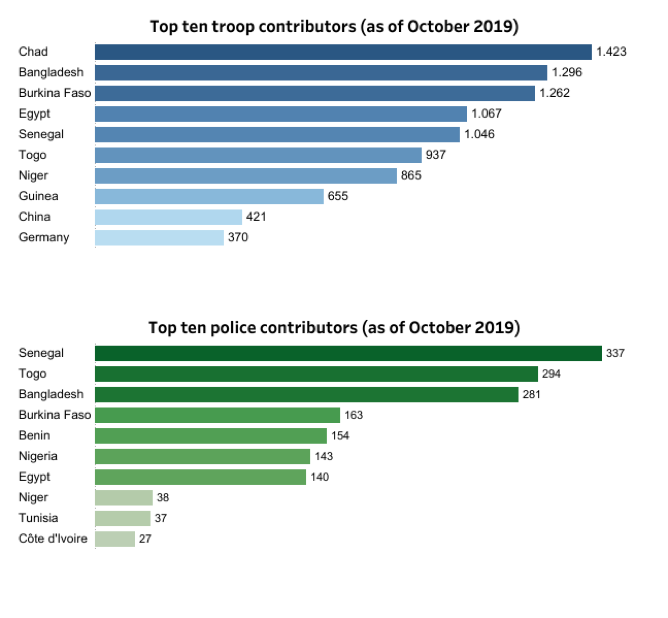

Seven years after, MINUSMA mission accounts with a deployment of 11,953 military personnel, 1,741 police personnel and 1,180 civilians (661 national - 585 international, including 155 United Nations Volunteers)[10] deployed in 4 different sectors: Sector North (Kidal, Tessalit, Aguelhoc) Sector South (Bamako) Sector East (Gao, Menaka, Ansongo) Sector West (Tombouctou, Ber, Diabaly, Douentza, Goundam, Mopti-Sevare). The $1 Billion budget mission (financed by UN regular budget on Peacekeeping operations) accounts with personnel from more than 50 different countries being Chad, Bangladesh or Burkina Faso the biggest contributors in terms of number of troops (Figure 1).

The command and control of the ground forces is headed by both commanders Lieutenant General Dennis Gyllensporre (military deployment) and MINUSMA Police Commissioner Issoufou Yacouba (police deployment). Regarding the political leadership of the mission, the Special Representative of the Secretary-general (SRSG) and Head of MINUSMA is Mr. Mahamat Saleh Annadif, an experienced diplomat on peace processes in Africa and former minister of Foreign Affairs of Chad.

Other international actors engaged

MINUSMA however is not the only international actor engaged in the security and political process of Mali. Institutions as the European Union are also on the ground helping specifically on the training of the Malian Army and helping develop their military capabilities.

The European Union Training Mission in Mali[11] (EUTM Mali) is composed of almost 600 soldiers from 25 European countries including 21 EU members and 4 non-member states (Albania, Georgia, Montenegro and Serbia). Since the beginning of the mission initially designed to end 15 months after the start in 2013 (First Mandate), there have been several extensions of the periods to end the mission by Council Decision (Second Mandate 2014-2016, Third Mandate 2016-2018) until today where we are on the Fourth Mandate (Extended until 2020 by Council Decision 2018/716/CFSP in May 2018). The strategic objectives of the 4th Mandate are:

-

1st to contribute to the improvement of the capabilities of the Malian Armed Forces under the control of the political authorities.

-

2nd to support G5 Sahel Joint Force, through the consolidation and improvement of the operational capabilities of its Joint Force, strengthening regional cooperation to address common security threats, especially terrorism and illegal trafficking, especially of human beings.

Regarding this last actor mentioned, the G5 Sahel Joint force (Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad) is an intergovernmental cooperation framework created on 16 February 2014 and seeks to fight insecurity and support development in the Sahel Region with the train and support of the European Union and external donors.

Its first operation, launched on July 2017, consisted in a Cross-Border Joint Force settled in Bamako to fight terrorism, cross-border organised crime and human trafficking in the G5 Sahel zone in the Sahel region. The United Nations Security Council welcomed the creation of this Joint Force in Resolution 2359 of 21 June 2017, which was sponsored by France[12]. At full operational capability, the Joint Force will have 5,000 soldiers (seven battalions spread across three zones: West, Centre and East). It is active in a 50 km strip on either side of the countries' shared borders. Later on, a counter-terrorism brigade is to be deployed to northern Mali.

Finally, as I explained before, France gradually withdrew from Mali and transformed Operation Serval to Operation Barkhane[13], a force, with approximately 4,500 soldiers, spread out between Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad to counter the terrorist threat on these territories. With a budget of nearly €600m per year, it is France's largest overseas operation and engages activities such as combat patrols, intelligence gathering and filling the Governance gap of the absent Government institutions.

Troop and Police contributors to MINUSMA [Source: UN].

Retrieved from MINUSMA Fact Sheet[25]

Assessment on the situation of MINUSMA

Since its establishment, MINUSMA has achieved some of its objectives in its early stages. From 2013 to 2016, the situation in Northern Mali improved, the numbers of civilians killed in the conflict decreased and large numbers of displaced persons could return home. In addition, MINUSMA supported the celebration of new elections in 2013 and assisted the peace process mainly between the Tuareg rebels and the Government. The peace process culminated in the 15 May 2015 with the Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali, commonly referred to as the Algiers Agreement[14][15].

The Algiers Agreement was an accord concluded between the Malian Government and two coalitions of armed groups that were fighting the government and against each other, being (i) the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA) and (ii) the Platform of armed groups (the Platform). Although imperfect, the peace agreement gave the basis to a continued dialogue and steps were made by the Government regarding the devolution of competences to regional institutions, laws of reconciliation and reintegration of combatants and resources devoted to infrastructure projects in the northern regions[16].

However, since 2016 the situation has deteriorated in several aspects. Violence has increased as jihadist groups have been attacking MINUSMA forces, the Forces Armées Maliennes (FAMA), and the Algiers Agreement signatories (CMA and the platform). As a consequence, MINUSMA has sustained an extraordinary number of fatalities compared to other recent UN peace operations.

Since the beginning of the Mission in 2013, 206 MINUSMA peacekeepers have died during service in Mali[17]. In the last report of Secretary General, it is noted that during the months of October, November and December 2019, there have been 68 attacks against MINUSMA troops in the regions of Mopti (46), Kidal (9), Ménaka (5), Timbuktu (4) and Gao (4) resulting in the deaths of two peacekeepers and eight contractors and in injury to five peacekeepers, one civilian and two contractors[18].

During this same period, the Malian Armed Forces have also experienced a loss of 193 soldiers and 126 injured. The deadliest attacks occurred in Boulikessi and Mondoro (Mopti Region) on 30 September; in Indelimane (Ménaka Region) on 1 November; and in Tabankort (Ménaka Region) on 18 November. MINUSMA provided support for medical evacuations for the national defence and security forces, as well as fuel and equipment to reinforce some camps.

In addition, during this last 3 months, there have been 269 incidents, in which 200 civilians were killed, 96 civilians were injured and 90 civilians were abducted. More than 85 per cent of deadly attacks against civilians took place in Mopti Region. Between 14 and 16 November, a series of attacks against Fulani villages in Ouankoro commune resulted in the killing of at least 37 persons.

As we can see from the data, Mopti region has further deteriorated regarding civilian protection and increased terrorist activity. What is more surprising is that this region in not located in the north but rather in the centre of the country. Mopti and Ségou regions in central Mali are where violence is increasingly spreading. Two closely intertwined drivers of violence can be distinguished: interethnic violence and jihadist violence against the state and its supporters.

The attacks directed primarily towards the Malian security forces and MINUSMA by jihadists have been committed by the jihadist group Katiba Macina, which is part of the GSIM (Le Groupe de Soutien à l'Islam et aux Musulmans), a merger organisation resulting from the fusion of Ansar Dine, forces from Al-Qaïda au Maghreb Islamique (AQMI), Katiba Macina and Katiba Al-Mourabitoune. This organisation formed in 2017 has triggered the retreat of an already relatively absent state in the central areas. The Katiba exerts violence against representatives of the state (administrators, teachers, village chiefs, etc.) in the Mopti region, provoking that only 30 to 40 per cent of the territorial administration personnel remains present. Additionally, only 1,300 security forces are stationed across the vast region (spanning 79,000 km²).

Between the Jihadist activities and the retaliation activities by government forces, there has been a collateral consequence as self-defence militias have proliferated. However, these militias have not only exerted self-defence but also criminal activities and competition over scarce local resources. To this problem we have to add the ethnic component where violence exerted by militias is associated with ethnic differences (mainly the Dogon and Fulani). Jihadists have instrumentalised this rivalry to gain sympathizers and recruits and turned the radicalisation problem and the interethnic rivalry into a vicious trap. The ethnicisation of the conflict reinforces the stigmatisation of the Fulani as "terrorists". Meanwhile, the state has tolerated and even cooperated with the Dogon militia to cope with the terrorist threat. However, these groups are supposedly responsible for human rights violations, which again fosters radicalisation among the Fulani population feeling they are left alone in this conflict. As a matter of fact, the Dogon Militia is alleged to be responsible of the 23 March assassination of 160 Fulani in the village of Ogossagou (Mopti Region)[19].

Northern Mali has not remained calm meanwhile, the Ménaka region has also experienced a violence raise. Recent counterterrorism efforts led by ethnically based militias resulted in a counterproductive effects leading to human rights violations and atrocities between Tuareg Daoussahaq and Fulani communities. Due to again the absence Malian security forces or MINUSMA blue helmets, civilians have had no choice but to rely on their own self-protection or on armed groups present in the area, escalating the vicious problem of violence as in the Mopti region.

Strategic dilemmas of MINUSMA

Given this situation, several dilemmas arise in the current situation in which the mission is. The original Mandate of MINUSMA for 5 years has already expired and now the mission is in a phase of renewal year by year, which makes it a suitable time to rethink the overall path where this mission should continue.

The fist dilemma arises given the split of the violent spots between the north and the centre of the country. MINUSMA was originally set up to stabilize the conflict in the north, but MINUSMA's 2019 Resolution 2480[20] has derived some attention and resources to the central regions and particularly on Protection of Civilians while maintaining its presence in the north too. However, the only problem is that this division on two has not come hand in hand with an increase in resources devoted to the mission, which means that attention paid to the central regions may be in spite of gains made in the north, making the MINUSMA mandate even more unrealistic.

This dilemma raises the problem of financing of the mission. As the years passes, financers of the mission (those that contribute to the General Budget on Peace Keeping Operations of UN) such as the US are getting impatient of not seeing results to a mission where $1 Billion is devoted out of the around $8 Billion of the General Budget. The problem is that for MINUSMA to accomplish its mission in Northern Mali, it has to make an enormous military and logistical effort. The ongoing violent situation calls for security precautions that tie up scarce resources which are no longer available for carrying out the mandate. To illustrate the problem, we can look at the expenditures of the mission and discover that around 80 per cent of its military resources are devoted to securing its own infrastructure and the convoys on which the mission depends to supply its instructions[21].

A final dilemma is related to the development of the terrorist threat. As we have analysed in this article, today's conflict in Mali is about terrorism and therefore requires counterterrorist strategies. However, there are people that state that MINUSMA should focus on the politics part of the conflict stressing its efforts on the peace agreement. Current counterterrorism efforts conducted by the Malian Army are highly problematic as they have fuelled local opposition due to its poor human rights commitment. It has been reported the use of ethnic proxy militias (Such as the Dogon militias in Mopti region) who are responsible for committing atrocities against the civilian population. This makes the Central Government to be an awkward and not very trustworthy partner for MINUSMA. At the same time, returning to political tasks alone may further destabilize the country and possibly the whole Sahel-West African region.

Conclusion

There is no doubt MINUSMA operates hostile environment where around half of all blue helmets killed worldwide through malign acts since 2013 have lost their lives. However, MINUSMA has been heavily criticised by public opinion in Mali and accused of passivity regarding protection of civilians whereas critics say, blue helmets have placed their own security above the rest. The has contributed to this public perception by using the mission's problems as a scapegoat for its own failures. However, the mission (with its successes and failures) brings more advantages than inconveniences to the overall process of stabilization of Mali[22].

As many diplomats in Bamako and other public officials stress, the mission and its chief, Mahamat Saleh Annadif, play an important role as mediators both in Bamako politics and with respect to the peace agreement. We cannot discredit the mission of its contribution to Mali's stabilisation. As a matter of fact, it is legitimate to claim that the situation would be much worse without MINUSMA. Yet, the mission has not stopped the spread of violence but rather slowed down the deterioration process of the situation.

While much presence is still needed in northern Mali, we should not forget that the core of the problem to Mali's instability is partly on the political arena and therefore needs mediation. Therefore, importance of continuing political and military support to the peace process should not be underestimated.

At the same time, we have seen the situation over protection of civilians has worsened in the central regions, which requires additional resources. Enhancing MINUSMA's outreach and representation might prevent the central regions from collapsing, though solutions need to be found to ensure stability in the long term through mediation as well. Further expanding the mission in the central regions without affecting the deployment in the north and, therefore, not risking the stability of those regions, would require that MINUSMA have additional resources. This would clearly be the best option for Mali.

Resources could for instance be devoted to improve the lack of mobility in the form of helicopters and armoured carriers to make it possible for the mission to expand its scope beyond the vicinity of its instructions. Staying in the instructions makes MINUSMA more of a target than a security provider and only provides security to its nearby zones where the base is physically present. In addition, the most dangerous missions are carried out by African peacekeepers despite lacking adequate means whereas European countries' peacekeepers are mostly based in MINUSMA's headquarters in Bamako, Gao, or Timbuktu. While European peacekeepers possess more sophisticated equipment such as surveillance drones and air support, African troops do not benefit from those and have to face the most challenging geographical and security environments escorting logistical convoys[23].

Additionally, by accelerating the re-integration of former rebels to the Malian security forces, encouraging Malian police training, and demonstrating increased presence through joint patrols in most instable areas to protect civilians are key to minimise the threat of further violence. Increased state visibility as we have analysed in this essay has driven to insecurity situations. Consequently, if it can be as much of the problem, it can also be the solution to re-establish some of its legitimacy alongside with the signatories of the Peace Accord to show good faith and engagement in the peace process[24].

In the end, any contribution MINUSMA can make will depend on the willingness of Malians to strive for an effective and inclusive government on the one hand and the commitment of the International community on the other. Supporting such a long-term process cannot be done on the cheap. Therefore, countries cannot continue to request to do more with the same or even less resources.

NOTES

[1] United Nations Peacekeeping (n.d.). Where we operate. [online] Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

[2] Renwick, D. (2015). Peace Operations in Africa. [online] Council on Foreign Relations. Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

[3] Welsh, M. Y. (2013, January 17). Making sense of Mali's armed groups. Al Jazeera. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

[4] Timeline on Mali (n.d.). New York Times. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

[5] Oberlé, T. (2012, March 22). Mali : le président renversé par un coup d'État militaire. Le Figaró. Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

[6] MINUSMA (n.d.). History. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

[7] Unscr.com (2012). Security Council Resolution 2085 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 23 Dec. 2019].

[8] BBC News. (2013). France confirms Mali intervention. [online] Available at [Accessed 24 Dec. 2019].

[9] Security Council Resolution 2100 - UNSCR (2013). Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

[10] MINUSMA (n.d.). Personnel. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

[11] EUTM Mali (n.d.). DÉPLOIEMENT - EUTM Mali. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

[12] France Diplomatie: Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (n.d.). G5 Sahel Joint Force and the Sahel Alliance. [online] Available at [Accessed 27 Dec. 2019].

[13] Ecfr.eu (2019). Operation Barkhane - Mapping armed groups in Mali and the Sahel. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

[14] Un.org (2015). AGREEMENT FOR PEACE AND RECONCILIATION IN MALI RESULTING FROM THE ALGIERS PROCESS. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

[15] Jezequel, J. (2015). Mali's peace deal represents a welcome development, but will it work this time? Jean-Hervé Jezequel. Available at [Accessed 8 Jan. 2020].

[16] Nyirabikali, D. (2015). Mali Peace Accord: Actors, issues and their representation. Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

[17] MINUSMA. MINUSMA Fact Sheet. Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

[18] Digitallibrary.un.org (n.d.). "UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali" OR MINUSMA - United Nations Digital Library System. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

[19] McKenzie, D. (2019). Ogossagou massacre is latest sign that violence in Mali is out of control. Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2019].

[20] Unscr.com (2019). Security Council Resolution 2480 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 10 Jan. 2019].

[21] United Nations Digital Library System (2019). Budget for the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali for the period from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020. [online] Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2020].

[22] Van der Lijn, J. (2019). The UN Peace Operation in Mali: A Troubled Yet Needed Mission - Mali. [online] ReliefWeb. Available at [Accessed 30 Dec. 2019].

[23] Lyammouri, R. (2018). After Five Years, Challenges Facing MINUSMA Persist. Available at [Accessed 6 Jan. 2020].

[24] Tull, D. (2019). UN Peacekeeping in Mali. [online] Swp-berlin.org. Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

[25] MINUSMA. MINUSMA Fact Sheet. Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

REFERENCES

United Nations Peacekeeping (n.d.). Where we operate. [online] Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

Renwick, D. (2015). Peace Operations in Africa. [online] Council on Foreign Relations. Available at [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

Timeline on Mali (n.d.). New York Times. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

Welsh, M. Y. (2013, January 17). Making sense of Mali's armed groups. Al Jazeera. Available at [Accessed 22 Dec. 2019].

MINUSMA (n.d.). History. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

Oberlé, T. (2012, March 22). Mali : le président renversé par un coup d'État militaire. Le Figaró. Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

Unscr.com (2012). Security Council Resolution 2085 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 23 Dec. 2019].

BBC News. (2013). France confirms Mali intervention. [online] Available at [Accessed 24 Dec. 2019].

MINUSMA (n.d.). Personnel. [online] Available at [Accessed 26 Dec. 2019].

EUTM Mali (n.d.). DÉPLOIEMENT - EUTM Mali. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

France Diplomatie: Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (n.d.). G5 Sahel Joint Force and the Sahel Alliance. [online] Available at [Accessed 27 Dec. 2019].

Ecfr.eu (2019). Operation Barkhane - Mapping armed groups in Mali and the Sahel. [online] Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

Un.org (2015). AGREEMENT FOR PEACE AND RECONCILIATION IN MALI RESULTING FROM THE ALGIERS PROCESS. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

Digitallibrary.un.org (n.d.). "UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali" OR MINUSMA - United Nations Digital Library System. [online] Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

United Nations Digital Library System (2019). Budget for the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali for the period from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020. [online] Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2020].

Van der Lijn, J. (2019). The UN Peace Operation in Mali: A Troubled Yet Needed Mission - Mali. [online] ReliefWeb. Available at [Accessed 30 Dec. 2019].

Tull, D. (2019). UN Peacekeeping in Mali. [online] Swp-berlin.org. Available at [Accessed 25 Dec. 2019].

McKenzie, D. (2019). Ogossagou massacre is latest sign that violence in Mali is out of control. Available at [Accessed 4 Jan. 2019].

Unscr.com (2019). Security Council Resolution 2480 - UNSCR. [online] Available at [Accessed 10 Jan. 2019].

Security Council Resolution 2100 - UNSCR. (2013). Available at [Accessed 2 Jan. 2019].

Nyirabikali, D. (2015). Mali Peace Accord: Actors, issues and their representation | SIPRI. Available at [Accessed 3 Jan. 2020].

Lyammouri, R. (2018). After Five Years, Challenges Facing MINUSMA Persist. Available at [Accessed 6 Jan. 2020].

Jezequel, J. (2015). Mali's peace deal represents a welcome development, but will it work this time? Jean-Hervé Jezequel. Available at [Accessed 8 Jan. 2020].

▲ A picture of Vladimir Putin on Sputnik's website

ESSAY / Pablo Arbuniés

A new form of power

Russia's growing influence in African countries and public opinion has often been overlooked by western democracies, giving the Kremlin a lot of valuable time to extend its influence on the continent.

Until very recently, western democracies have looked at influence efforts from authoritarian countries as nothing more than an exercise of soft power. Joseph S. Nye defined soft power as a nation's power of attraction, in contrast to the hard power of coercion inherent in military or economic strength (Nye 1990). However, this influence does not fit the common definition of soft power as 'winning hearts and minds'. In the last years China and Russia have developed and perfected extremely sophisticated strategies of manipulation aimed towards the civilian population of target countries, and in the case of Russia the role of Russia Today should be taken as an example.

These strategies go beyond soft power and have already proved their effectiveness. They are what the academia has recently labelled as sharp power (Walker 2019). Sharp power aims to hijack public opinion through disinformation or distraction, being an international projection of how authoritarian countries manipulate their own population (Singh 2018).

Sharp power strategies are being severely underestimated by western policy makers and advisors, who tend to focus on more classical conceptions of the exercise of power. As an example, the "Framework document" issued by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies on Russia-Africa relations (Mora Tebas 2019). The document completely ignores sharp power, labelling Russian interest in communication markets as no more than regular soft power without taking into consideration the disinformative and manipulative nature of these actions.

A growing interest in Africa

Over the past 20 years, many international actors have shifted their interest towards the African continent, each in a different way.

China has made Africa a major geopolitical target in recent years, focusing on economic investments for infrastructure development. Such investments can be noticed in the Ethiopian dam projects such as the Gibe III, or in the Entebbe-Kampala Expressway in Uganda.

This could be considered as debt-trap diplomacy, as China uses infrastructure investments and development loans to gain leverage over African countries. However, there is also a key geopolitical interest, especially in those countries with access to the network Sea and the Indian Ocean, due to the One Belt One Road Initiative. This project requires a net of seaports, where Kenya, and specifically the port of Lamu, could play a key role in becoming a hub for trade in East Africa (Hurley, Morris and Portelance 2019).

Also, Chinese investments are attractive for African countries because they do not come with prerequisites of democratisation or transparent administration, unlike those from western countries.

Yet, even though both China and Russia use sharp power as part of their foreign policy strategies, China does barely use it in Africa, since its interests in the continent are more economic than political. This is based on the view that China is more keen to exploit Africa's natural resources (Mlambo, Kushamba and Simawu 2016) than anything else.

On the other hand, Russia has both economic and military interests in the region. This is exemplified by the case of Sudan, where in addition to the economic interest in natural resources, there is also a military interest in accessing the network Sea. In order to achieve these goals, the first step is to grant stability in the country, and it can be achieved through ensuring that public opinion supports the government and accepts Russian presence.

The idea of a Russian world-Russkiy spanish medical residency program-has grown under Putin and is key to understanding the country's soft and sharp power strategies. It consists on the expansion of power and culture using any means possible in order to regain the lost superpower status.

However, this approach must not be seen only as a nostalgic push to regain status, but also from a purely pragmatic point of view, since economic and practical factors have "pushed aside ideology" in the competition against the West (Warsaw Institute 2019).

The recent Russia-Africa Summit (23-24 October 2019), that took place in Sochi, Russia, proves how Russia has pivoted towards Africa in recent years, offering infrastructure, energy and other investments as well as arms deals and different advisors. The outcome of this pivoting is being quite beneficial for Moscow in strategic terms.

The Kremlin's interest in Africa was not remarkable until the post Crimea invasion. The economic sanctions imposed after the occupation of Crimea forced Russia to look further abroad for allies and business opportunities. For instance, as part of this policy there was a more robust involvement of Russia in Syria.

The Russian strategy for the African continent involves benefiting favourable politicians through political and military advisors and offering control on average influence (Warsaw Institute 2019). In exchange, Russia looks for military and energy supply contracts, mining concessions and infrastructure building deals. Moreover, on a bigger picture, Russia-as well as China-aims to reduce the influence of the US and former colonial powers France and the UK.

Leaked documents published by The Guardian (Harding and Buerke 2019), show this effort to gain influence on the continent, as well as the strategies followed and the degree of cooperation with the different powers-from governments to opposition groups or social movements.

However, the growth of Russia's influence in Africa cannot be understood without the figure of Yevgeny Prigozhin, an extremely powerful oligarch which, according to US special counsel Robert Mueller, was critical to the social average campaign for the election of Donald Trump in 2016. He is also linked to the foundation of the Wagner group, a private military contractor present among other conflicts in the Syrian war.

Prigozhin, through a network of enterprises known as 'The Company' has been for long the head of Putin's plans for the African continent, being responsible of the growing number of Russian military experts involved with different governments along the continent, and now suspected to lead the push to infiltrate in the communication markets.

Between 100 and 200 spin doctors have already been sent to the continent, reaching at least 10 different countries (Warsaw Institute 2019). Their focus is on political marketing and especially on social average, with the hope that it can be as influential as in the Arab Springs.

Main targets

Influence in the average is one of the key aspects of Russia's influence in Africa, and the main targets in this aspect are the Central African Republic, Madagascar, South Africa and Sudan. Each of these countries has a potential for Russian interests, and is targeted on different levels of cooperation, from weapons deals to spin doctors (Warsaw Institute 2019), but all of them are targets for sharp power strategies.

However, it is hard for a foreign government to directly enter the communication markets of another country without making people suspicious of its activities, and that is where The Company plays its role. Through it, pro-Russian publishing house lines are fed to the population of the target states by acquiring already existing average platforms-such as newspapers or television and radio stations-or creating new ones directly under the supervision of officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, this ensures that the dominant frames fit Russia's interests and that of its allies.

Also, the presence of Russian international average is key to its sharp power. Russia Today and Sputnik have expanded their reach by associating with local entities in Eritrea, Ivory Coast, etc. Russian radio services have been expanded to Africa as well as a key factor in both soft and sharp power.

Finally, social average are a great way of distributing disinformation, given its global reach and the insufficient amount of fact-checkers devoted to this area. There, not only Russian average can participate but also bots and individual accounts are at the service of the Kremlin's interests.

Madagascar

Although Madagascar is viewed by the Kremlin as a high cooperation partner, it doesn't seem to have much to offer in geopolitical terms other than tan mining concessions for Russian companies. Therefore, Russian presence in Madagascar was widely unexpected.

During the May 2019 election, Russia backed six different candidates, but none of them won. In the final stages of the campaign, the Kremlin changed its strategy and backed the expected and eventual winner, Andry Rajoelina (Allison 2019). This could be considered a fiasco and ignored because of the disastrous result, but there is a key aspect that shows how Russia is trying to shape public opinion across the continent.

Although political advisors and spin doctors were only one part of the plan, Russia managed to produce and distribute the biggest mass-selling newspaper along the country with more than two million copies every month (Harding and Buerke 2019). Though it did not seem to have any major impact on the short term, it could be an important asset for shaping public opinion on the long run.

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is of major geopolitical relevance in the whole of the African continent. Due to its location as well as its cultural and ethnic features, it is viewed by the Kremlin as the gate to the whole continent. It is the zone of transition between the Muslim north of the continent and the Christian south (Harding and Buerke 2019).

Given the complicated situation and the context of the ongoing civil war, it can be considered as an easy target for foreign powers. This is mainly due to the power structures being weakened by the war. Russia is part of the UN peacekeeping mission in the CAR, in a combination of soft and hard power. Also, a Russian training centre is operative in the country, and both Moscow and Bangui are open to the inauguration of a Russian military base.

Russia played a key role in the peace deal of February 2019, and since 2017 Valery Zakharov, a former Russian intelligence official, has been an adviser to CAR's president. All of this, if the peacekeeping operations are successful, would lead to an immense political debt in favour of the Kremlin.

The mineral richness of the CAR is another asset to consider due to the reserves of gold and high-quality diamonds. Also, there is a big business opportunity in rebuilding a broken country, and Russian oligarchs and businessmen would certainly be interested in any public contracts regarding this matter.

In the CAR, Russia exerts sharp power not only through social average, but also through two print publications and a radio station, which still have limited influence (Harding and Buerke 2019). Through such means, Russia is consistently feeding its frames narratives to a disoriented population, which given the unstable context, would be an easy target to manipulate. Moreover, the possibility to create a favourable dominant post conflict narrative would render public opinion more likely to accept Russian presence in the future.

Sudan

Sudan is of major geostrategic importance for Russia among many other actors. For long time both countries have had economic, political and military relations, leading to Sudan being considered by the Kremlin as a level 5 co-operator, the highest possible (Harding and Buerke 2019). This relation is enforced by Sudan's constant claims of aggressive acts by the United States, for which it demands Russia's military assistance.

Also, Sudan is rich in uranium, bearing the third biggest reserves in the world. Uranium is a key raw material to build a major power nowadays, and Russia is always keen on new sources of uranium to bolster its nuclear industry.

Moreover, Sudan is key in regional and global geopolitics because it offers Russia a possibility to have a military base with access to the network Sea. Given the amount of trade routes that go through its waters, the Kremlin would be very keen to have said access. Many other powers have shown interest in this area, such as the Gulf States, or China with its base in Djibouti being operational since 2017.

For all these reasons. Sudan is a very special element in Russia's plans, and thus its level of commitment is greater than in other countries. The election to take place on April 2020 could be considered as one of the most important challenges for democracy in the short term. Russia is closely monitoring the situation in order to draw an efficient plan of action.

Before the end of Omar al-Bashir's presidency, Russia and Sudan enjoyed good relations. Russian specialists had prepared reforms in economic and political matters in order to ensure the continuity in power of Bashir, and his fall was a blow to these plans.

However, Russia will devote many resources to amend the situation in the Sudan parliamentary and presidential election, that will take place in April 2020. In a ploy to maintain power, Al Bashir mirrored the measures employed against opposition protesters in Russia. These tactics consist of using disinformation and manipulated videos in order to portray any opposition movement as anti-Islamic, pro-Israeli or pro-LGBT. Given the fact the core of Sudan's public opinion is mostly conservative and religious, Russia's plan consists on manipulating it towards its desired candidate or candidates (Harding and Buerke 2019).

In order to ensure that the Russian framing was dominant, social average pages like Radio Africa's Facebook page or Sudan Daily were presented like news pages, while being in fact part of a Russian-backed influence network in central and northern Africa (Alba and Frenkel 2019). The information shown has been supportive of whatever government is in power, and critical of the protesters (Stanford Internet Observatory 2019), which shows that Russia's prioritary interest is a stable government and weak protesters.

Another key part of the strategy has been pressuring the government to increase the cost of newsprint to limit the possibilities of countering the disinformation distributed with the help of Russian advisors (Harding and Buerke 2019). The de-democratization of information can prove to be very effective, even more taking into account the fact that social average is not as powerful in Sudan as it is in western countries, so owning the most popular means of communication allows to create a dominant frame and impose it to the population without them even noticing.

South Africa

The economic context of South Africa, with a large economy, a rising middle class and a good market overall, is quite interesting for business and could be one of the reasons why Russia has such an interest in the country. Also, South Africa can be seen as an economic gateway to the southern part of the African continent.

South Africa is a key country for the global interest of Russia. Not only for its mineral richness and business opportunities, but mainly for its presence in BRICS. Russia attempts to use BRICS as a global counterbalance in a US dominated international landscape.

Russia is interested in selling nuclear technology to its allies, and South Africa is no exception. The presence of South Africa in BRICS is key to understand why such a deal would be so interesting for Russia. BRICS may not offer the possibility to create a perfect counter-balance for western powers, mainly due to the unsurpassable discrepancies among the involved countries, but its ability to cooperate comprehensively on limited shared projects and objectives can be of critical relevance (Salzman 2019).

The presence in the country of Afrique Panorama and AFRIC (Association for Free Research and International Cooperation), shows how Russia attempts to exert its influence. Both pages are linked to Prigozhin, but they are disguised as independent. AFRIC was involved in the elections of Zimbabwe, South Africa, Madagascar and DRC (Grossman, Bush and Diresta 2019).

In fact, if public opinion could be shaped in order to make Russia's interests like nuclear cooperation acceptable by South Africa, the main obstacle would be surpassed, and a comprehensive plan of cooperation would be in play sooner than later.

The elections of May 2019 were one of the main priorities for Russia. The election saw Cyril Ramaphosa elected, as successor of Jacob Zouma. Ramaphosa is known to have openly congratulated Nicolás Maduro for his second inauguration and holds good relations with Vietnam. This are indicators of a willingness to have good relations even with anti-western powers, which is of big interest for the Kremlin. Furthermore, he has a vast business experience, being the architect of the most powerful trade union in the country among other achievements and initiatives, which would see him open to strike deals with Russian oligarchs in the mineral or energetic fields.

All this considered, South Africa is of extreme relevance for Russia, and thus its efforts to be able to shape public opinion. This could be used to favour the implementation of nuclear facilities as well as electing favourable politicians, creating a political debt to be exploited someday. For now, any activity has been limited to tracking and getting to understand public opinion. However, the creation of new average under some form of control by the Kremlin is one of the priorities for the coming years (Harding and Buerke 2019), and could prove a very valuable asset if it's successfully achieved. Also, despite what was said in the case of Sudan, the importance of social average is not to be forgotten or underestimated, especially given the advantage of English being an official language in the country.

The bigger picture

From a more theorical point of view, that of the Flow and Contra-flow paradigm, Russia attempts to set the political diary through mass average control, as well as impose its own frames or those that benefit its allies. Also, given the proportions of the project, we could talk about an attempt to go back to the cultural imperialism doctrines, where Russia attempts to pose its narrative as a counterflow of the western narratives. This was mainly seen during the cold war, when global powers attempted to widely spread their own narratives through controlling said information flows, arguably as a form of cultural imperialism.

This can be seen as an attempt to counterbalance the power of the US and western powers by attempting to shift African countries towards non-western actors. And African countries may be interested in this idea, since being the centre of the competition could mean better deals and business opportunities or investments being offered to them.

It would be a mistake to think that Russia's sharp power in Africa is just a tool to help political allies get to power or maintain it. Beyond that, Russia monitors social conflicts and attempts to intensify them in order to destabilise target countries or external powers (Alba and Frenkel 2019). Such is the case in Comoros, where Prigozhin employees were tasked to explore the possibilities of intensifying the conflict between the local government and the French administration (Harding and Buerke 2019). Again on a broader picture of things, the attempt to develop an African self-identity through the use of sharp power looks to reduce the approval of influence of western democracies on the continent, thus creating an ideal context for bolstering dependence on the Russian administration either through supply contracts or political debt.

In conclusion, the recent growth of Russia's soft and above all sharp power in Africa could potentially be one of the political keys in the years to follow, and it is not to be overlooked by western democracies. Global average, supranational entities and public administrations should put their efforts on providing civil society with the tools to avoid falling for Russia's manipulative tactics and serve as guarantors of democracy. The most immediate focus should be on the US 2020 election, since the worst-case scenario is that the latest exercises of Russia's sharp power in Africa are a practice towards a new attempt at influencing the US presidential election in 2020.

REFERENCES

Alba, Davey, and Sheera Frenkel. 2019. "Russia Tests New Disinformation Tactics in Africa to Expand Influence." The New York Times, 30 October.

Allison, Simon. 2019. "Le retour contrarié de la Russie en Afrique." Courrier international, 5 August.

Ashraf, Nadia, and Jeske van Seters. 2020. "Africa and EU-Africa partnership insights: input for estonia's new africa strategy." ECDPM.

Grossman, Shelby, Daniel Bush, and Renée Diresta. 2019. "Evidence of Russia-Linked Influence Operations in Africa."

Harding, Luke, and Jason Buerke. 2019. "Leaked documents reveal Russian effort to exert influence in Africa." The Guardian, 11 June. Accessed November 25, 2019.

Hurley, John, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance. 2019. "Examining the debt implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a policy perspective." Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development (EnPress Publisher) 3 (1): 139.

Madowo, Larry. 2018. Should Africa be wary of chinese debt.

Mlambo, Courage, Audrey Kushamba, and More Blessing Simawu. 2016. "China-Africa Relations: What Lies Beneath?" Chinese Economy (Routledge) 49 (4): 257-276.

Mora Tebas, Juan A. 10/2019. http://www.ieee.es/. 2019. ""Rusiáfrica": Russia's return to the African "big game"." Paper. framework IEEE. Last accessed 30 Nov. 2019. http://www.ieee.es/.

Nye, Joseph. 1990. Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. London: Basic Books.

Salzman, Rachel S. 2019. Russia, BRICS, and the disruption of global order. Georgetown University Press.

Singh, Mandip. 2018. "From Smart Power to Sharp Power: How China Promotes her National Interests ." Journal of Defence Studies.

Standish, Reid. 2019. Putin Has a Dream of Africa. Foreign Policy.

Stanford Internet Observatory. 2019. "Evidence of Russia-Linked Influence Operations in Africa."

Walker, C. and Ludwig, J. 2019. "The Meaning of Sharp Power." Foreign Affairs.

Warsaw Institute. 2019. "Russia in Africa: weapons, mercenaries, spin doctors." Strategic report, Warsaw.

![Farewell of Espérance Nyirasafari (left) as minister of Gender and Family Promotion, in Rwanda's capital in 2018 [Rwanda's Gov.] Farewell of Espérance Nyirasafari (left) as minister of Gender and Family Promotion, in Rwanda's capital in 2018 [Rwanda's Gov.]](/documents/10174/16849987/rwanda-blog.jpg)

▲ Farewell of Espérance Nyirasafari (left) as minister of Gender and Family Promotion, in Rwanda's capital in 2018 [Rwanda's Gov.]

ESSAY / María Rodríguez Reyero

South Africa is ranked 17th in the World Economic Forum's 2020 Global Gender Gap Index[1] (a two place increase from 2019), while Rwanda is ranked 9th (a three place decline from the previous year). Interestingly, Spain is ranked 8th (a major gain of 11 places in one year). Since 2018, Spain has made a gain of 21 places, which is only rivaled by countries like Madagascar (22), Mexico and Georgia (25) and Ethiopia (35).