Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with Categories Global Affairs Global .

[Eduardo Olier, La guerra económica global. essay sobre guerra y Economics (Valencia: Tirant lo Blanc, 2018), 357 pgs].

review / Emili J. Blasco

War is to geopolitics what economic war is to geoeconomics. Eduardo Olier, the driving force behind another related field in Spain, economic intelligence, has devoted much of his research and professor to the latter two concepts, which are highly dependent on each other.

The book The Global Economic War ( 2018) is a sort of colophon of what could be considered a trilogy, whose previous volumes were Geoeconomics. Las claves de la Economics global (2011) and Los ejes del poder económico. Geopolitics of the global chessboard (2016). Thus, first there was a presentation of geoeconomics, as a specific field inseparable from geopolitics (the use of the Economics by the powers as a new instrument of force), and then a commitment to the concretisation of the different vectors in struggle, with a prolific use of graphs and statistics, unusual in intellectual production in Spanish for a work of knowledge dissemination. This third book is somewhat more philosophical: it has a certain broom-like quality, finishing off or rounding off ideas that had previously appeared in some cases less contextualised in their conceptual framework , and integrating all the reflections into a more compact edifice. With hardly any graphics, here the narrative flows with more attention to the argumentative process.

The global economic war, moreover, puts the focus on confrontation. "Economic warfare is the reverse of political warfare, just as military wars, always political in origin, end up being economic wars," Olier says. He shares the view that "any economic transaction has at its heart a danger of conflict", that "trade is never neutral and contains within it a principle of violence": at final, that "war is the result of a flawed economic exchange ". The author warns that as a country increases its welfare at the same time it boosts its military capacity to try to gain more power. This need not necessarily lead to war, but economic dependence, according to Olier, increases the chances of war. "The possibility of increasing economic benefits from a potential victory increases the likelihood of starting an armed conflict," he says.

Olier is indebted to the development of this discipline carried out in France, where the School of Economic Warfare was born in 1997 as an academic centre attached to the technical school Libre des Sciences Commerciales Appliquées. These programs of study place special emphasis on economic intelligence, which in France is closely linked to the actions of the state secret services in defence of the international position of large French companies, whose interests are closely linked to national imperatives when it comes to strategic sectors. Olier represents in Spain the high school Choiseul, a French think tank dedicated to these same issues.

Among the interesting contributions of The Global Economic War is the dating and interrelation of the successive versions of the internet, globalisation and NATO: the beginning of the Cold War, 1950 (globalisation 1.0 and NATO 1.0); the dissolution of the USSR, 1991 (globalisation 2.0); creation of the internet, 1992 (web 1.0); entrance of Poland in NATO (NATO 2.0); birth of social networks, 2003 (web 2.0); annexation of Crimea by Russia and consolidation of cyberspace in all activities, 2014 (globalisation 3.0, NATO 3.0 and web 3.0). In this schedule he adds at another point the currency war: currency war 1.0 (1921-1936), 2.0 (1967-1987), 3.0 (2010); this is not an outlandish addendum , but very much to purpose, as Olier argues that, if raw materials are one of the keys to economic warfare, currencies "are no less the subject commodity of the Economics, as they can mark who has and who does not have power".

All this reflection is set in the context of a chain of cycles and counter-cycles, where economic and political cycles are interconnected. reference letter Referring to Kondratiev's long cycles, which are renewed every half century, he recalls that the last cycle would have begun in 1993, so that "the expansionary period should last until 2020, before falling and fill in the 50-year cycle, more or less, towards 2040, when a new expansion would begin" (Olier writes this without foreseeing how the current pandemic would, for the time being, reinforce the prediction).

Just as in geopolitics there are a few imperatives, geoeconomics is also governed by some laws, such as those that move directly to the Economics: when there is economic growth, leave unemployment rises and inflation rises, and vice versa; the conflict for a country and its international environment is when Economics goes down, unemployment rises and so does inflation, giving rise to stagflation status .

Geoeconomics as discipline forces us to look squarely at present and future realities, without allowing ourselves to be fobbed off with wishful thinking about the world we would like, which is why the outlook on the European Union ends up being sombre. Olier believes that Europe will experience its instability without revolutions, but with a loss of global power. "The bureaucratisation of the Structures government in Brussels will only help to increase populism. Brexit (...) will be a new silent revolution that will diminish the power of the whole. This will be increased by the different visions and strategies" of the member states. "A circumstance that will give greater power to Russia in Europe, while the United States will look to the Pacific in its staff conflict with China".

In his opinion, only France and Britain, because of their military power, show signs of wanting to participate in the new world order. The other major European countries are left to one side: Germany sample that economic power is not enough, Italy has enough to try not to disintegrate politically... and Spain is "the weakest link in the chain", as was the case just over eighty years ago, when the new order that was taking shape in Europe first confronted the major powers in the Spanish Civil War before the outbreak of the Second World War. Olier warns that "the nirvana of affluent European societies" will be seriously threatened by three phenomena: the instability of internal politics, mass migrations from Africa and demographic ageing that will cause them to lose dynamism.

Javier Blas & Jack Farchy, The World For Sale. Money, Power and the Traders. Who Barter the Earth's Resources (London: Random House Business, 2021) 410 pp.

review / Ignacio Urbasos

In what is probably the first book dedicated exclusively to the world of commodities trading, Javier Blas and Jack Farchy attempt to delve into a highly complex industry characterised by the secrecy and opacity of its operations. With more than two decades of journalistic experience covering the world of natural resources, first for the Financial Times and later for Bloomberg, the authors use valuable testimonies from professionals in the sector to construct an honest account.

The book covers the history of the commodity trading world, beginning with the emergence of small intermediaries responding to the growing need after World War II to supply raw materials to Western economies in their reconstruction processes. The oil nationalisation of the 1960s offered an unprecedented opportunity for these intermediaries to enter a sector that had hitherto been restricted to the traditional oil majors. The new petro-states, now in control of their own oil production, needed someone to buy, store, transport and ultimately sell their oil abroad. This opportunity, coupled with the oil crises of 1973 and 1978, allowed these intermediaries to reap unprecedented spoils: a booming sector with enormous price volatility, which allowed for profits in the millions. With the fall of the Soviet Union and the socio-economic collapse of a large part of the socialist world, companies dedicated to the purchase and sale of raw materials found a new market, with enormous natural resources and without any subject experience in the capitalist market Economics . With the entrance of the 21st century and the so-called " CommoditySupercycle", trading companies enjoyed a period of exorbitant profits in a context of rapid global growth led by China. It is in these last two decades that Vitol, Trafigura, Glencore or Cargill increased their revenues exponentially, with a global presence and managing all commodities, both physically and financially, through subject .

Throughout the different chapters, the authors tackle the complexities of the world of trading without complexes. On many occasions, these companies have enabled countries in crisis to avoid economic collapse by offering financing and the possibility of finding a market for their resources, as in the paradoxical case of Cuba, which threw itself into the arms of Vitol to supply oil in exchange for sugar during the "Special Period". However, the dominant position of these companies vis-à-vis states in an enormously vulnerable status has ended up generating relationships in which the benefits are unequally shared. A paradigmatic case that is exhaustively covered in the book is that of Jamaica in the 1970s, which was heavily indebted and impoverished, when Marc Rich and Company became one of the country's main creditors in exchange for de facto control of the country's bauxite and aluminium mining production. These situations continue today, with Glencore as Chad's largest creditor and a key player in the country's fiscal austerity policies.

Nor do the authors hide the unscrupulousness of these companies in maximising their profits. Thus, they supplied apartheid South Africa with oil or clandestinely sold Iranian crude oil in the midst of the Hostage Crisis. Similarly, these big companies have never had problems dealing with autocrats or being active in major corruption schemes. Nor have environmental scandals been a rarity for these companies, which have been forced to pay millions in compensation for negligent management of toxic products, as in the case of Glencore and the sulphur spill in Akouedo, which resulted in 95,000 victims and the payment of 180 million to the government of Côte d'Ivoire. It is not surprising that many of the executives of these companies have ended up in prison or persecuted by the law, as in the case of Mark Rich, founder of Glencore, who had to live in Spain until he obtained a controversial pardon from Bill Clinton on the last day of his presidency.

There is no doubt that The World For Sale by Javier Blas and Jack Farchy provides a better understanding of a sector as opaque as the commodities trade. An industry dominated by companies with complex fiscal Structures transnational presence and whose activities often remain outside of public scrutiny. As an industry of growing economic and political importance, it is essential to read this book to gain a critical and realistic perspective on an essential part of our globalised Economics .

review / Emili J. Blasco

The discipline of "political risk" can be conceived in a restrictive way, as usual, referring to the prospective analysis of disruptions that, by states and governments, can affect political and social stability and the regulatory framework and, therefore, the interests of investors, companies and economic sectors. This conception, which globalisation also leads to call "geopolitical risk", is only a part - in fact, the minor part - of Nigel Gould-Davies' approach, who by putting the adjective "global" in the degree scroll of his book is referring to a conceptually more general political risk, merged with fields such as corporate reputation, public affairs and business diplomacy.

The author claims that the relationship with the environment is essential for a business and calls for a company's management to always have someone manager of engagement (which we could translate as involvement, commitment, participation or partnership): an engager who has the same level of authority as the engineer who knows how to manufacture the product and the salesperson who knows how to monetise it; someone specialised in "persuading" external actors - governments and civil society groups - of the company's goodness, creating "alignments" that are beneficial for business. Engagement at both the national and international level, if the activity or interests go beyond one's own borders, giving rise to "corporate diplomacy", as the current "increase in political risks means that a company needs a foreign policy".

Gould-Davies sees these more political issues not as an "impertinent intrusion" into markets, but as something endogenous to them. So the business, in addition to attending to production and marketing issues, must also pay equal attention to a third dimension: engagement with political and social actors to avoid or overcome risks that it faces in that external sphere. This is "a third activity and a third role to carry it out: a new political piece in the mechanism of value creation".

The author emphasises management on the present and the very short term future deadline, and downplays the importance of short and medium term prospective analysis deadline which has been the preserve of political risk analysts. He complains that the latter have paid "too much attention to prediction, with its frequent disappointments, and too little to engagement"; " engagement, on the other hand, requires relatively little prediction beyond the short deadline". "There is a lot of unbalanced political risk activity, producing a lot of analysis and prediction, but much less guidance on what to do".

Moreover, unlike the usual political risk analysis, which is more focused on the actions of states or governments, the concept the author uses extends very specifically to the pressures that can arise from civil society. "The new political risks emerge from non-state social forces: consumers, investors, public opinion, civil society, local communities and the media. They do not seek to challenge ownership or rights to use productive assets. They do not seek to destroy, take or block. Their focus is narrower: they usually seek to regulate the terms on which production and trade take place (...) Their motive is usually an ethical commitment to justice and equity. Their goal is to mitigate the wider adverse impacts of corporate activity on others; they are selfless rather than self-serving".

Gould-Davies notes that while previously the norm was government threats in development or emerging countries with less stable societies and unconsolidated rule of law, today pressures on business are increasing in developed nations. "The likelihood of major conflict and de-globalisation is increasing, but more importantly, its impact is shifting towards the developed world," he writes. Moreover, the fact that there is less and less social peace in Western countries is an increasingly disturbing element: "Sustained civil violence in a highly developed country is no longer a black swan, but a grey swan: improbable but conceivable; possible to define, but impossible to predict".

By focusing on management in the present and characterising the activity as engagement, which is in itself very communication-centred, Gould-Davis stretches the classical concept of political risk, which has been more oriented towards analysis and foresight, too far. In doing so, he treads on activities that are becoming widely known development for their own sake, such as corporate communication and reputation or influencing regulatory issues through lobbying or public affairs management functions.

[Marko Papic, Geopolitical Alpha. An Investment Framework for Predicting the Future (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2021), 286 pages].

review / Emili J. Blasco

"In the post-Trump and post-Brexit era, geopolitics is all that counts," says Marko Papic in Geopolitical Alpha, a book on political risk whose purpose aims to provide a method or framework from work for those involved in foresight analysis. consultant in investment funds, Papic condenses here his experience in a profession that has gained attention in recent years due to growing national and international political instability. development Whereas risk factors used to be concentrated in emerging countries, they are now also present in the advanced world.

With the book's degree scroll , Papic designates a process of analysis in which geopolitics proper, in its most geographically related sense, is only one part of the considerations to be taken into account, as the author argues that political and then economic (and financial) determinants matter first. For the whole of the analysis and the estimates it gives rise to, Papic uses the qualifier "alpha geopolitics" (or "alpha geopolitics"), as referring to a plus or reinforced geopolitics: one that takes into account political or macroeconomic constraints in addition to traditional geopolitical imperatives.

With the book's degree scroll , Papic designates a process of analysis in which geopolitics proper, in its most geographically related sense, is only one part of the considerations to be taken into account, as the author argues that political and then economic (and financial) determinants matter first. For the whole of the analysis and the estimates it gives rise to, Papic uses the qualifier "alpha geopolitics" (or "alpha geopolitics"), as referring to a plus or reinforced geopolitics: one that takes into account political or macroeconomic constraints in addition to traditional geopolitical imperatives.

At bottom it is a nominalist question, in a collateral battle in which the author unnecessarily entangles himself. It is arguably a settling of scores with his former employer, the George Friedman-led Stratfor, whom Papic praises in his pages, but who he seems to covertly criticise for basing much of his foresight on the geography of nations. To suggest that, however, is to make a caricature of Friedman's solid analysis. In any case, Papic has certainly reinforced his training with programs of study financials and makes useful and interesting use of them.

The central idea of the book, leaving aside this anecdotal rivalry, is that in order to determine what governments will do, one should look not at their stated intentions, but at what constrains them and compels them to act in certain ways. "Investors (and anyone interested in political forecasting) should focus on material constraints, not politicians' preferences," says Papic, adding a phrase that he repeats, in italics, in several chapters: "Preferences are optional and subject to constraints, while constraints are neither optional nor subject to preferences.

These material constraints, according to the order of importance established by Papic, are political conditioning factors (the majority available, the opinion of the average voter, the level of popularity of the government or the president, the time in power or the national and international context, among other factors), macroeconomic and financial constraints (budgetary room for manoeuvre, levels of deficit, inflation and debt, value of bonds and currency....) and geopolitical ones (the imperatives that, derived initially from geography - the particular place that countries occupy on the world stage - mark the foreign policy of nations). To that list, add constitutional and legal issues, but only to be taken into account if the aforementioned factors do not pose any constraint, for it is well known that politicians have little trouble circumnavigating the law.

The author, who presents all this as a method or framework of work, considers that the fact that there may be irrational politicians who entrance do not submit to objective material constraints does not derail the approach, since this status is eventually overcome because "there is no irrationality that can alter reality". However, he admits as a possible objection that, just as the opinion of the average voter conditions the actions of the politician, there may be a "hysterical society" that conditions the politician and is not itself affected in the short term deadline by objective constraints that make it bend to reality. "The time it takes for a whole society to return to sanity is an unknown and impossible prognosis," he acknowledges.

Papic proposes a reasonable process of analysis, broadly followed by other analysts, so there is no need for an initial, somewhat smug boast about his personal prospective skills, which are indispensable for investors. Nevertheless, the book has the merit of a systematised and rigorous exhibition .

The text is punctuated with specific cases, the analysis of which is not only well documented but also conveniently illustrated with tables of B interest. Among them is one that presents the evolution of pro-euro opinion in Germany and the growing Europhile position of the average German voter, without which Merkel would not have reached the previously unthinkable point of accepting the mutualisation of EU debt. Or those that note how England, France and Russia's trade with Germany increased before the First World War, or that of the United States with Japan before the Second World War, exemplifying that rivalry between nations does not normally affect their commercial transactions.

Other interesting aspects of the piece include his warning that "the class average will force China out of geopolitical excitement", because international instability and risk endangers Chinese economic progress, and "keeping its class average happy takes precedence over dominance over the world". "My constraint-based framework suggests that Beijing is much more constrained than US policymakers seem to think (...) If the US pushes too hard on trade and Economics, it will threaten the prime directive for China: escape the middle-income trap. And that is when Beijing would respond with aggression," says Papic.

Regarding the EU, the author sees no risks for European integration in the next decade. "The geopolitical imperative is clear: integrate or perish into irrelevance. Europe is not integrating because of some misplaced utopian fantasy. Its sovereign states are integrating out of weakness and fear. Unions out of weakness are often more sustainable in the long run deadline. After all, the thirteen original US colonies integrated out of fear that the UK might eventually invade again.

Another suggestive contribution is to label as the "Buenos Aires Consensus" the new economic policy that the world seems to be moving towards, away from the Washington Consensus that has governed international economic standards since the 1980s. Papic suggests that we are exchanging the era of "laissez faire" for one of a certain economic dirigisme.

The inclusion of private investment and the requirement of efficient credits differ from the overwhelming amount of loans from Chinese state banks.

The active role of China as lender to an increasing number of countries has forced the United States to try to compete in this area of "soft power". Until last decade the US was clearly ahead of China in official development assistance, but Beijing has used its state-controlled banks to pour loans into ambitious projects worldwide. In order to better compete with China, Washington has created the US International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC), combining the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and with USAID's Development Credit Authority (DCA).

▲ The US agency helped to provide clean, safe, and reliable sanitation for more than 100,000 people in Nairobi, at the end of 2020 [USIDFC].

ARTICLE / Alexandria Casarano

It is not easy to know the complete amount of the international loans given by China in recent years, which skyrocketed from the middle of last decade. Some estimates say that the Chinese state and its subsidiaries have lent about US$ 1.5 trillion in direct loans and trade credits to more than 150 countries around the globe, turning China into the world's largest official creditor.

The two main Chinese foreign investment banks, the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank, were both established in 1994. The banks have been criticised for their lack of transparency and for blurring the lines between official development assistance (ODA) and commercial financial arrangements. To address this issue, Beijing founded the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) in April of 2018. The CIDCA will oversee all Chinese ODA activity, and the Chinese Ministry of Commerce will oversee all commercial financial arrangements going forward.

An additional complaint about Chinese foreign investment concerns "debt-trap diplomacy." Since the PRC first announced its "One Belt One Road" initiative in 2013, the Chinese government has steadily increased its investment in the developing world even more dramatically than it had in the early 2000's (when Chinese foreign aid was increasing annually by approximately 14%). At the 2018 China-Africa Convention Forum, the PCR pledged to invest US$ 60 billion in Africa that year alone. The Wall Street Journal said of the PRC in 2018 that it was "expanding its investments at a pace some consider reckless." Ray Washburn, president of the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), called the Chinese One Belt One Road initiative a "loan-to-own" program. In 2018, this was certainly the case with the Chinese funded Sri Lankan port project, which led the Sri Lankan government to lease the port to Beijing for a 99-year period as a result of falling behind on payments.

OPIC, founded in 1971 under the Nixon administration, was recommended for elimination in the Trump administration's 2017 budget. However, following the beginning of the US-China trade war in 2018, Washington reversed course completely. President Trump's February 2018 budget recommended increasing OPIC's funding and combining it with other government programs. These recommendations manifested themselves in the Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development (BUILD) Act, which was passed by Congress on October 5, 2018. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) called the BUILD Act "the most important piece of U.S. soft power legislation in more than a decade."

The US International Development Finance Corporation

The principal achievement of the BUILD Act was the creation of the US International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC), which began operation as an independent agency on December 20, 2019. The BUILD Act combined OPIC with USAID's Development Credit Authority to form the USIDFC and established an annual budget of US$ 60 billion for the new organisation, which is more than double OPIC's 2018 budget of US$ 29 billion.

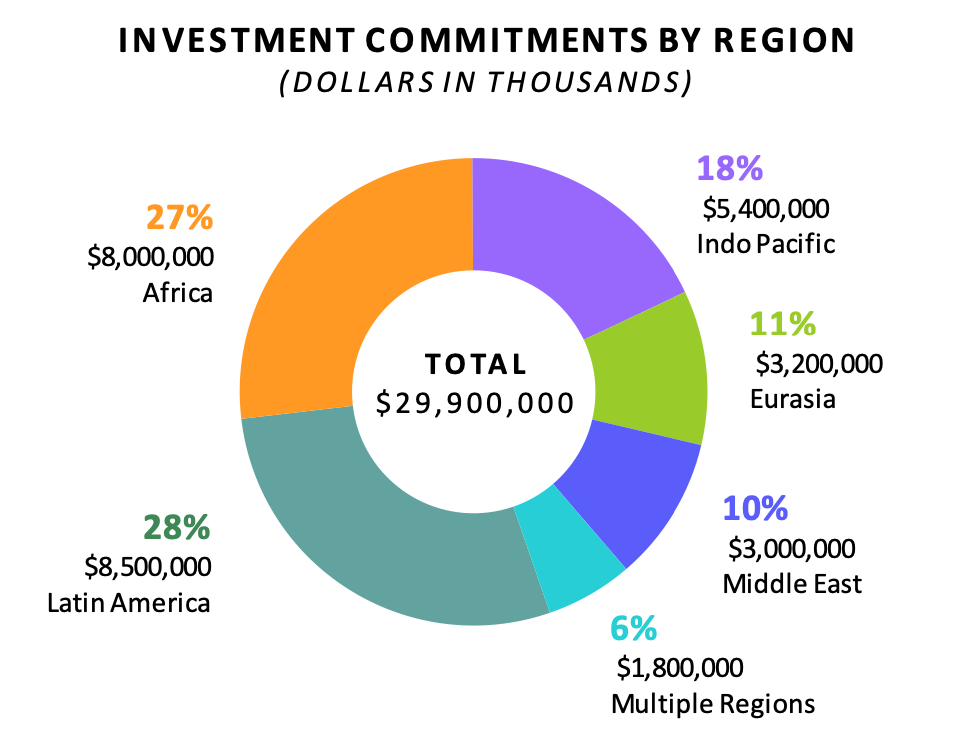

USIDFC's investment commitments by region for the FY 2020. The US$ 29.9 billion is only a fraction of the agency's budget [USIDFC].

According to the Wall Street Journal, OPIC "has been profitable every year for the last 40 years and has contributed US$ 8.5 billion to deficit reduction," a financial success which can primarily be attributed to project management fees. As of 2018, OPIC managed a portfolio valued at US$ 23 billion. OPIC's strong fiscal track record, combined with both the concept of government program streamlining and the larger context of geopolitical competition with China, generated bipartisan support for the BUILD Act and the USIDFC.

The USIDFC has several key new capacities which OPIC lacked. OPIC's business was limited to "loan guarantees, direct lending and political-risk insurance," and suffered under a "congressional cap on its portfolio size and a prohibition on owning equity stakes in projects". The USIDFC, however, is permitted under the BUILD Act to "acquire equity or financial interests in entities as a minority investor."

Both the USIDFC currently and OPIC before its incorporation are classified as Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). DFIs seek to "crowd-in" private investment, that is, attracting private investment that would not occur otherwise. This differs from the Chinese model of state-to-state lending and falls in line with traditional American political and economic philosophy. According to the CSIS, "The USIDFC offers [...] a private sector, market-based solution. Moreover, it fills a clear void that Chinese financing is not filling. China does not support lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and it rarely helps local companies in places like Africa or Afghanistan grow".

In the fiscal year of 2020, the most USIDFC's investments were made in Latin America (US$ 8.5 billion) and Sub-Saharan Africa (US$ 8 billion). Lesser but still significant investments were made in the Indo-Pacific region (US$ 5.4 billion), Eurasia (US$ 3.2 billion), and Middle East (US$ 3 billion). This falls in line with the USIDFC's goal to invest more in lower and lower-middle income countries, as opposed to upper middle countries. OPIC previously had fallen into the pattern of investing predominantly in upper-middle countries, and while the USIDFC is still legally authorised to invest in upper-middle income countries for national security or developmental motives.

These investments serve to further US national interests abroad. According to the USIDFC webpage, "by generating economic opportunities for citizens in developing countries, challenges such as refugees, drug-financed gangs, terrorist organisations, and human trafficking can all be addressed more effectively". Between 2002 and 2014, financial commitments in the DFI sector have increased sevenfold, from US$ 10 billion to US$ 70 billion. In our increasingly globalized world, international interests increasingly overlap with national interests, and public interests increasingly overlap with private interests.

Ongoing USIDFC initiatives

The USIDFC has five ongoing initiatives to further its national interests abroad: 2X Women's Initiative, Connect Africa, Portfolio for Impact and Innovation, Health and Prosperity, and Blue Dot Network. In 2020, the USIDFC "committed to catalyzing an additional US$ 6 billion of private sector investment in global women's economic empowerment" by joining the 2X Women's Initiative which seeks global female empowerment. About US$1 billion for this US$ 6 billion commitment has been specially pledged to Africa. Projects that fall under the 2X Women's Initiative include equity financing for a woman-owned feminine hygiene products online store in Rqanda, and "expanding women's access to affordable mortgages in India".

Continuing the USIDFC's special focus on Africa follows the Connect Africa initiative, under which the USIDFC has pledged US$ 1 billion to promote economic growth and connectivity in Africa. The Connect Africa initiative involves investment in telecommunications, internet access, and infrastructure.

Under the Portfolio for Impact and Innovation initiative, the USIDFC has dedicated US$ 10 million to supporting early-stage businesses. This includes sponsoring the Indian company Varthana, which offers affordable online learning for children whose schools have been shut down due to the Covid-19 crisis.

The Health and Prosperity initiative focuses on "bolstering health systems" and "expanding access to clean water, sanitation, and nutrition". Under the Health and Prosperity initiative, the USIDFC has dedicated US$ 2 billion to projects such as financing a 200+ mile drinking water pipeline in Jordan.

The Blue Dot Network initiative, like the Connect Africa initiative, also invests in infrastructure, but on a global scale. The Blue Dot Network initiative differs from the aforementioned initiatives in being a network. Launched in November 2019, the Blue Dot Network seeks to align the interests of government, private enterprise, and civil society to facilitate the successful development of infrastructure around the globe.

It is important to note that these five initiatives are not entirely separate. Many projects fall under several initiatives at once. The Rwandan feminine products e-store project, for example, falls under both the 2X Women's initiative and the Health and Prosperity initiative.

![A Challenger 2 tank on Castlemartin Ranges in Pembrokeshire, Wales, fires a 'Squash-Head' practice round [UK MoD]. A Challenger 2 tank on Castlemartin Ranges in Pembrokeshire, Wales, fires a 'Squash-Head' practice round [UK MoD].](/documents/16800098/0/tanque-blog.jpg/ad2d496a-0f7c-43ad-2221-8aa7f316a01a?t=1621877556817&imagePreview=1)

▲ A Challenger 2 tank on Castlemartin Ranges in Pembrokeshire, Wales, fires a 'Squash-Head' practice round [UK MoD].

COMMENTARY / Jairo Císcar Ruiz

At the end of last summer, two news pieces appeared in the forums and specialised magazines of the military field in the Anglo-Saxon world. The first of them was the forecast of the continuity (and worsening due to the current pandemic) of the spending cuts suffered in the UK Defence budget since 2010. The second, linked to the first, was the growing rumors of a possible withdrawal of the Challenger 2 tanks, which were already reduced to a quarter of their original strength. At a time of great economic instability, it seemed that the UK's strategic vision had decided to focus on its main assets to maintain its deterrent power and its projection of force: the very expensive nuclear arsenal and the maintenance and expansion of new naval groups in order to host the F-35B.

However, both pieces of news have been quickly overtaken by the announcement of the Boris Johnson executive to inject about 22 billion dollars over 4 years to take British power back to the levels of 30 years ago. Also, the decommissioning of battle tanks was dismissed by ministerial sources, who argued that it was simply a possibility raised in the "Integrated Review" that is being carried out by the British Ministry of Defence.

Although the waters have calmed down, the discussion that has arisen as a result of these controversies seems extremely interesting, as well as the role that armoured units will have on the battlefield of the future. This article aims to make a brief reflection, identifying possible scenarios and their implications.

The first of them It is a reality: the United Kingdom must improve its armoured forces, which run the risk of becoming obsolete, not only in the face of threats (Russia has had since 2015 the T-14 Armata, a 5th generation tank; and recently the modernized version of the mythical T-90, Proryv-3), but also in front of their allies, such as France or Germany, which are already starting the project to replace their respective armor with the future European Main Battle Tank. It is not only a matter of improving their operational capabilities, but also of evolving their survival on the battlefield.

At a time when military technology is advancing by leaps and bounds (hypersonic projectiles; battlefield dominated by technology; extensive use of drones ...), it is necessary to rethink the traditional way of waging war. In the last Nagorno-Karabakh crisis, images and evidence of the effectiveness of the use of Israeli "suicide" drones could be seen against groups of infantry, but also against armoured vehicles and tanks. Despite Foreign Policy accusing poor training and the complex terrain as the main factors for these casualties, the question is still up in the air: does the "classic" tank as we know it still have a place on the battlefield?

Experience tells us yes[1]. The tank is vital in large military operations, although, as noted above, new threats must be countered with new defenses. To this day, the tank remains the best vehicle to provide direct fire quickly and efficiently, against other armor, infantry, and reinforced enemy positions. By itself it is an exceptional striking force, although it must always act in accordance with the rest of the deployed troops, especially with Intelligence, Logistics units and the Infantry. It should not be forgotten that in a battlefield characterized by hybrid warfare, it is necessary to consider the increasingly changing environment of threats.

Sensors and detection systems on the battlefield are persistently more innovative and revolutionary, capable of detecting armoured vehicles, even if they are camouflaged; when integrated with lethal precision firing systems, they make concealing and wearing heavy armor a challenge. There are technical responses to these threats, from countering electronic direction finding through spoofing and jamming, to mounting active protection systems on vehicle hulls.

Despite the above, obviously, the battle tank continues to be a great investment in terms of money that must be made, questionable in front of the taxpayer in an environment of economic crisis, although at the strategic level it may not be.

There are also those who broke a spear in favour of withdrawing the tanks from their inventories, and it seems that today they regret having made this decision. The United Kingdom has the example of the army of the Netherlands, which in 2011 withdrew and sold to Finland 100 of its 120 Leopard 2A6s as a means of saving money and changing military doctrine. However, with Russia's entry into Ukraine and its increasing threats to NATO's eastern flank, they soon began to miss the armoured forces' unique capabilities: penetrating power, high mobility that enables turning movements to engulf the enemy, maneuverability, speed, protection, and firepower. In the end, in 2015, they handed over their last 20 tanks (crews and mechanics included) to the German army, which since then has a contingent of a hundred Dutch, forming the Panzerbataillon 414. Knowing how important the concept of "lessons learned" is in military planning, perhaps the UK should pay attention to this case and consider its needs and the capabilities required to meet them.

A roadmap to the middle position would be to move towards an "army of specialization", abandoning its armoured units and specializing in other areas such as cyber or aviation; but this would only be possible within the framework of a defence organization more integrated than NATO. Although it is only a distant possibility, the hypothetical and much mentioned European Army -of which the United Kingdom would most likely be excluded after the Brexit- could lead to the creation of national armed forces that would be specialised in a specific weapon, relying on other countries to fulfil other tasks. However, this possibility belongs right now to the pure terrain of reverie and futurology, since it would require greater integration at all levels in Europe to be able to consider this possibility.

In the end we find the main problem when organising and maintaining an army, which is none other than money. On many occasions this aspect, which is undoubtedly vital, completely overshadows any other consideration. And in the case of a nation's armed forces, this is very dangerous. It would be counterproductive to ignore the tactical and strategic aspects to favour just the purely pecuniary ones. The reality is that Western armed forces, whether from the United Kingdom or any other NATO country, face not only IEDs and insurgent infantry in the mountainous regions of the Middle East, but also may have to confront peer rivals equipped with huge armoured forces. Russia itself has about 2,000 battle tanks (that is, not counting other armoured vehicles, whether they are capable of shooting rounds or not). China increases that figure up to 6,900 (more than half are completely out of date, although they are embarking on a total remodeling of the Chinese People's Army in all its forces). NATO does not forget the challenges, hence the mission "Enhanced Forward Presence" in Poland and the Baltic Republics, in which Spain contributes a Tactical Group that includes 6 Leopard 2A6 Main Battle Tanks, 14 Pizarro Infantry Fighting Vehicles, and other armored infantry transports.

Certainly, war is changing. We can't even imagine how technology will change the battlefield in the next decade. Sometimes, though, it is better not to get ahead of time. Taking all aspects into account, perhaps the best decision the UK Ministry of Defence could make would be to modernize its tank battalions to adapt them to the current environment, and thus maintain a balanced military with full operational capabilities. It is plausible to predict that the tank still has a journey in its great and long history on the battlefield, from the Somme, to the war of the future. Time (and money) will tell what ends up happening.

[1] Doubts have existed since the very "birth" of the battle tank during the First World War. In each great war scene of the twentieth century that has contributed significant technological innovations (World War I; Spanish Civil War; World War II; Cold War; Gulf ...) it seemed that the tank was going to disappear under new weapons and technologies (first reliability problems, then anti-tank weapons and mines, aviation, RPG's and IED's...) However, armies have learned how to evolve battle tanks in line with the times. Even more valuable, today's tanks are the product of more than 100 years of battles, with many lessons learned and incorporated into their development, not only on a purely material level, but also in tactics and training.

![A B-1B Lancer unleashes cluster munitions [USAF]. A B-1B Lancer unleashes cluster munitions [USAF].](/documents/16800098/0/cluster-bombs-blog.jpg/86c6e39e-4ca3-dac3-dfb3-cdba300bbac2?t=1621877460129&imagePreview=1)

▲ A B-1B Lancer unleashes cluster munitions [USAF].

ESSAY / Ana Salas

The aim of this paper is to study the international contracts on cluster bombs. Before going deeper into this issue, it is important to understand the concept of international contract and cluster bomb. "A contract is a voluntary, deliberate, legally binding, and enforceable agreement creating mutual obligations between two or more parties and a contract is international when it has certain links with more than one State."[1].

A cluster bomb is a free-fall or directed bomb that can be dropped from land, sea, or air. Cluster bombs contain a device that releases many small bombs when opened. These submunitions can cause different damages, they are used against various targets, including people, armored vehicles, and different types of material. It is an explosive charge designed to burst after that separation, in most cases when impacting the ground. But often large numbers of the submunitions fail to function as designed, and instead land on the ground without exploding, where they remain as very dangerous duds.

The main problem with these types of weapons is that they may cause serious collateral damage such as the death of thousands of civilians. Because of that, the legality of this type of weapon is controversial. Out of concern for the civilians affected by artifacts of this type, the Cluster Bomb Convention was held in Dublin, Ireland in 2008. There, a treaty was signed that prohibited the use of these weapons. Not all countries, though, signed the treaty; major arms producers, such as the United States, Russia and China, are not parties in the convention.

Among other things, the Convention proposed a total ban on cluster munitions, the promotion of the destruction of stocks in a period of 8 years, the cleaning of contaminated areas in 10 years, and assistance to the victims of these weapons.

Convention on Cluster Munitions: geopolitical background

The antecedents of this convention are in the recognition of the damage produced by the multiple attacks that have been carried out with cluster munitions. The International Handicap Organization has produced a report that offers concrete and documented data on the victims of cluster bombs around the world. In Laos[2], the attacks were designed to prevent enemy convoys make use of dense vegetation to camouflage among the trees. Furthermore, in this way it was not necessary to use ground troops. In Kosovo (1999), the targets were military posts, road vehicles, troop concentrations, armored units, and telecommunications centers. In Iraq cluster bombs have been used several times. During Operation "Desert Storm" in 1991, US forces dropped almost 50,000 bombs with more than 13 million submunitions on Iraq in air operations alone (not taking into account those dropped from the sea or by artillery). Estimates suggest that a third did not explode, and were found on roads, bridges and other civil infrastructure.

Pressure for an international ban on cluster bombs has recently intensified, following Israel's bombardments with these weapons in southern Lebanon in the summer of 2006. Also, in Afghanistan, in 2001 and 2002, during the US offensive, more than 1,200 cluster bombs with almost 250,000 submunitions were dropped against Taliban military instructions and positions. These targets were near towns and villages, whose civilian population was affected. UN demining teams estimate that around 40,000 munitions did not explode. These have been the main concern of NGOs. On the one hand, because of the large percentage of civilians who have been affected by the cluster bombs and on the other hand, due to the amount of submunitions that did not explode at the time and that are in the affected areas, being an even greater risk for the security of the civilian population or even for their agriculture in those lands.

Due to the great commotion over the death of thousands of civilians and after several attempts, a convention on such munitions was adopted in Dublin, where more than 100 countries had come together for an international agreement. The Convention on Cluster Munitions was adopted on May 30, 2008, in Dublin and signed on December 3-4, 2008 in Oslo, Norway. The Convention on Cluster Munitions entered into force on August 1, 2010.

One of the major problems addressed in the Convention was the threat posed by submunitions that do not explode as expected, and which remain in the area as a mortal danger, turning the affected area into a large minefield where the civilian population is the most vulnerable. A study indicates that 20-30% of these bombs do not explode either due to manufacturing defects, or to falls in soft areas or in trees, for example.

Articles 3 and 4 of the Convention are of great importance. Article 3 refers to the stockpile, storage, and destruction of cluster bombs. Here all Parties haves the obligation of making sure to destroy their stored cluster bombs no later than 8 years. Article 4, on the cleaning and destroying of cluster munition remnants and education on risk reduction, is intended to protect possible victims from the danger of bombs that have not exploded. Article 5 reinforces the obligation of the signatory parties to assist the victims of cluster bombs.

After the convention there is a double deal on cluster bombs. Since the destruction of the entire arsenal of these ammunitions and submunitions was approved, the affected companies and the countries involved will have a new challenge in hiring companies that carry out the extinction of these reserves.

Producers

The main manufacturers of cluster bombs are the United States, Russia, China, Israel, Pakistan, and India. Approximately 16 states are the largest producers of this ammunition and submunition worldwide, and none of these countries adhered to the convention on cluster munitions. Some of the countries involved are Greece, South Korea, North Korea, Egypt, Iran, Poland, Turkey, Brazil, Singapore, Romania, and Poland. The date on which the cluster munitions were produced is not clear because of the lack of transparency and the data available.

A total of 85 companies have produced, along history, cluster bombs or their essential parts. Many of these companies are headquartered in the United States or Europe, but others are state-owned industries located in developing countries. Cluster munition production involves the manufacturing and integration of a large number of parts, including metal parts, explosives, fuses, and packaging materials. All components are seldom produced by a single company in the same state. This makes it difficult to determine the true extent of the international trade in cluster munitions.

International trade on cluster bomb has slackened. As the cluster munition monitor of 2017 states, the US company Textron Systems Corporation, for example, has slowed production of the CBU-105[3] weapon due to "reduced orders, and claimed that the current political environment has made it difficult to obtain sales approvals from the executive branch".

Manufactures are also adapting their production to international regulations. Following a study by Pax[4] on "Worldwide Investments in cluster munitions," Avibras (Brazil), Bharat Dynamics Limited (India), China Aerospace Science and Industry (China) or Hanwha (South Korea) are some of the companies that develop or produce cluster bombs according to the definition given by the Dublin Convention in 2008.

It is important to warn about the existing sensitivity regarding the production of cluster bombs. Undoubtedly, they pose a serious problem from the point of view of civil protection, but many companies engaged in the production and the funders of this kind of weapons have a high interest in keeping them legal.

There are very controversial weapons. Many countries insist on that cluster munitions are legal weapons, that, although not essential, have great military use. Some states believe that submunitions can be accurately targeted to reduce damage to civilians, meaning that military purposes can be isolated in densely populated areas. On the other hand, others believe that the ability of cluster munitions to destroy targets just as effectively throughout the attack area can cause those using them to neglect the target, thus increasing the risk of civilian casualties.

The future of International contracting on cluster bombs

As Jorge Heine defines the "New Diplomacy", it requires the negotiation of a wide range of relationships with the state, NGOs and commercial actors. "As middle powers have demonstrated, through joining forces with NGOs, they have actually succeeded in augmenting their power to project their interests into the international arena."[5] Cluster munition is an example of this case.

Because of this, parties forming international contracts for the purchase and financing of cluster bombs are forced to change the object of the cluster bomb business. As mentioned earlier, the new business will be the destruction of these weapons, rather than their production. Especially munitions with high submunition failure rates. For this reason, countries such as Argentina, Canada, France, UK, Denmark, Norway, Spain and more have promoted a new business on the destruction of the storage of cluster bombs. As a result, cluster munitions move away from their useful life and have more chances of being destroyed than of being sold for profit.

By financing companies that produce cluster munitions, financial institutions (in many cases states themselves) help these companies to produce the weapon. But to achieve an effective elimination of cluster bombs, more than a convention is needed. The effort requires national legislation that reflects that purpose. Domestic governments must provide clear guidelines by introducing and enforcing legislation that prohibits investment in cluster munitions producers.

Conclusion

As a military tactic, the use of cluster bombs provides a high percentage of success. A good number of states and armies defend that they are effective weapons, sometimes even decisive ones, depending on the circumstances and the context. It is often argued that using another type of weapon to achieve the same objective would require more firepower and use more explosives, and that this would cause even greater collateral damage. At the same time, and to avoid the low reliability of these weapons, some armies have begun to modernize their arsenals and to replace older weapons with more modern and precise versions that incorporate, for example, guidance or self-destruct systems. Their main objective in developing cluster bombs is to compensate for precision failures with more munitions and, on the other hand, to allow a greater number of targets to be hit in less time.

Advances in technology can certainly reduce some of the humanitarian problems generated by the less advanced types of cluster bombs but a good number of military operations are currently peace operations, where the risk generated by these products also becomes a military concern, not just humanitarian. For example, to address the issue of unexploded ordnance, weapons are being developed that have self-destruction or, at least, self-neutralization mechanisms[6].

There is great uncertainty about how the norms of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) are interpreted and whether they are applied rigorously in the case of cluster munitions, given the lack of precision and reliability of these weapons. The Convention on Cluster Munitions gives hope, but we must consider the different current situations and how they can change. We also have to take into account that this agreement leaves open many possibilities of circumventing what has been signed. For example, guided or self-destructive cluster bombs do not fall under the umbrella of this pact.

Despite the provisions of International Humanitarian Law, existing cluster munitions have caused large numbers of civilian casualties in various conflicts. A better implementation of the IHL, including the Protocol on Explosive Remnants of War, will not be able to fully address the problems caused by these weapons. There is a need for specific rules on these munitions as outlined above.

[1] Renzo Cavalieri and Vincenzo Salvatore, An introduction to international contract law, Torino: Giappichelli, 2018.

[2] During the years 1964 to 1973, Laos was bombed by the United States. The attacks were intended to cut off North Vietnamese supply lines and support Laotian government forces in their fight against communist rebels.

[3] CBU-105 is a free fall cluster bomb unit of the United States Air Force.

[4] Pax is a peace organisation with the aim of "bringing peace, reconciliation and justice in the world".

[5] Matthew Bolton and Thomas Nash, 'The Role of Middle Powe-NGO Coalitions in Global Policy: The Case of the Cluster Munitions Ban', Global Policy, Vol. 1, No. 2 (May 2010), pp 172-184.

[6] Some essential component for the operation of the bomb is deactivated.

COMMENT / Sebastián Bruzzone

"We have failed... We should have acted earlier in the face of the pandemic". These are not the words of a political scientist, scientist or journalist, but of Chancellor Angela Merkel herself addressing the 27 other leaders of the European Union on 29 October 2020.

Anyone who has followed the news from March to today can easily realise that no government in the world has been able to control the spread of the coronavirus, except in one country: New Zealand. Its prime minister, the young Jacinda Ardern, closed the borders on 20 March and imposed a 14-day quarantine on New Zealanders returning from overseas. Her "go hard, go early" strategy has yielded positive results compared to the rest of the world: fewer than 2,000 infected and 25 deaths since the start of the health crisis. And the question is: how have they done it? The answer is relatively simple: their unilateral behaviour.

The most sceptical to this idea may think that "New Zealand is an island and has been easier to control". However, it is necessary to know that Japan is also an island and has more than 102,000 confirmed cases, that Australia has had more than 27,000 infected, or that the United Kingdom, which is even smaller than New Zealand, has more than one million infected. The percentage of cases out of the total population of New Zealand is tiny, only 0.04% of its population has been infected.

As the world's states waited for the World Health Organisation (WHO) to establish guidelines for a common response to the global crisis, New Zealand walked away from the body, ignoring its wildly contradictory recommendations, which US President Donald J. Trump called "deadly mistakes" while suspending America's contribution to the organisation. Japanese Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aro went so far as to say that the WHO should be renamed the "Chinese Health Organisation".

The New Zealand case is an example of the weakening of today's multilateralism. Long gone is the concept of multilateral cooperation that gave birth to the United Nations (UN) after the Second World War, whose purpose was to maintain peace and security in the world. The foundations of global governance were designed by and for the West. The powers of the 20th century are no longer the powers of the 21st century: emerging countries such as China, India or Brazil are demanding more power in the UN Security committee and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The lack of common values and objectives between developed and emerging countries is undermining the legitimacy and relevance of last century's multilateral organisations. In fact, China already proposed in 2014 the creation of the Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) as an alternative to the IMF or the World Bank.

The European Union is not spared from the multilateral disaster either because it has been attributed the shared skill in common security matters in subject of public health (TFEU: art. 4.k)). On 17 March, the European committee took the incoherent decision to close external borders with third states when the virus was already inside instead of temporarily and imperatively fail the Schengen Treaty. On the economic front, inequality and suspicion between the debt-prone countries of the North and the South have increased. The refusal of the Netherlands, Finland, Austria and other frugals to the unconditional financial aid required by a country like Spain, which has more official and political cars than the rest of Europe and the United States combined, called into question one of the fundamental principles on which the European Union was built: solidarity.

Europe has been the perfect storm in a sea of uncertainty and Spain, the eye of the hurricane. The European economic recovery fund is a term that overshadows what it really is: a financial bailout. A total of 750 billion euros divided mainly between Italy, Portugal, France, Greece and Spain, which will receive 140 billion euros and will be paid back by our grandchildren's children. It seems fanciful that the first health aid Italy received came from third states and not from its EU partners, but it became a reality when the first planes from China and Russia landed at Fiumicino airport on 13 March. The pandemic is proving to be an examination of conscience and credibility for the EU, a sinking ship with 28 crew members trying to bail out the water that is slowly sinking it.

Leading scholars and politicians confirm that states need multilateralism to respond jointly and effectively to the great risks and threats that have crossed borders and to maintain global peace. However, this idea collapses when it is realised that today's leading figure in bilateralism, Donald J. Trump, is the only US president since 1980 not to have started a war in his first term, to have brought North Korea closer, and to have secured recognition of Israel by Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates.

It is time to shift geopolitics towards updated and consensus-based solutions based on cooperative governance rather than global governance led by obsolete and truly powerful institutions. Globalist multilateralism that seeks to unify the actions of countries with very disparate cultural and historical roots under a single supranational entity to which they cede sovereignty can cause major clashes within the entente, provoke the departure of some of the disgruntled members, the subsequent extinction of the intended organisation and even enmity or a rupture of diplomatic relations.

However, if states with similar values, laws, customary norms or interests decide to come together under a treaty or create a regulatory institution, even while ceding just and necessary sovereignty, the understanding will be much more productive. Thus, a network of bilateral agreements between regional organisations or between states has the potential to create more precise and specific objectives, as opposed to signing a globalist treaty where long letters and lists of articles and members can become smoke and mere declarations of intent as has been the case with the Paris Climate Change Convention in 2015.

This last idea is the true and optimal future of International Office: regional bilateralism. A world grouped in regional organisations made up of countries with similar characteristics and objectives that negotiate and reach agreements with other groups of regions through dialogue, peaceful understanding, the art of diplomacy and binding pacts without the need to cede the soul of a state: sovereignty.

[Peter Zeihan, Desunited Nations. The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World (New York: Harper Collins, 2020) 453 pgs]

review / Emili J. Blasco

The world seems to be heading towards what Peter Zeihan calls "the great disorder". His is not a doomsday vision of the international order for the mere pleasure of wallowing in pessimism, but a fully reasoned one. The retreat of the United States is leaving the world without the ubiquitous presence that secured the global structure we have known since the Second World War, forcing other countries into more insecure intercontinental trade and to seek their livelihoods in an environment of "disunited nations".

The world seems to be heading towards what Peter Zeihan calls "the great disorder". His is not a doomsday vision of the international order for the mere pleasure of wallowing in pessimism, but a fully reasoned one. The retreat of the United States is leaving the world without the ubiquitous presence that secured the global structure we have known since the Second World War, forcing other countries into more insecure intercontinental trade and to seek their livelihoods in an environment of "disunited nations".

Zeihan has long been drawing consequences from his seminal idea, set out in his first book, The Accidental Superpower (2014): the success of fracking has given the US energy independence, so it no longer needs Middle Eastern oil and will progressively withdraw from much of the world. In his next book, The Absent Superpower (2016), he detailed how US withdrawal will leave other countries unable to secure important maritime trade routes and reduce the proliferation of developed contacts in this era of globalisation. The latter has now been accelerated by the Covid pandemic, which came as a third volume, Desunited Nations (2020), was about to be published. Zeihan did not have time to include a reference letter to the ravages of the virus, but there was no need because his text went in the same direction in any case.

Zeihan, a geopolitical analyst who worked with George Friedman at Stratfor and now has his own signature, looks this time at how the different powers will adapt to the 'great disorder' and which of them have the best prospects. The book is "about what happens when the global order is not only crumbling, but when many leaders feel that their countries will be better off tearing it down". And it's not just about the Trump administration: "the push for American retreat did not start with Trump, nor will it end with him," says Zeihan.

The author believes that, in the new outline, the United States will remain a superpower, China will not achieve a hegemonic position and Russia will continue its decline. Among other minor powers, France will lead the new Europe (not Germany; while the British are "doomed to a multi-year depression"), Saudi Arabia will give more concern to the world than Iran and Argentina will have a better future than Brazil.

To focus on the US-China rivalry, it would be good to pick up on some of Zeihan's arguments for his scepticism about the consolidation of China's rise.

To be an effective superpower, China needs greater control of the seas. The problem is not to build a large, outward-facing navy, but, since it is already difficult to sustain such a huge effort over time, it must also simultaneously have "a huge defensive navy and a huge air force and a huge internal security force and a huge army and a huge intelligence system and a huge special forces system and a global deployment capability".

For Zeihan, the question is not whether China will be the next hegemon, which "it cannot be", but "whether China can even hold together as a country". The impossibility of feeding its entire population on its own, the lack of sufficient energy sources of its own, strong territorial imbalances and demographic constraints, such as the fact that there are 41 million Chinese men under the age of 40 who will never be able to marry, are all factors that work against China's ability to remain united.

It is not uncommon for American authors to predict a future collapse of China. However, episodes such as the coronavirus, initially seen as a serious stumbling block for Beijing, have never really cut short the forward march of the Asian colossus, even though China's economic growth figures have naturally been moderating over the years. This is why many people's bad omens can sometimes be interpreted more as wishful thinking than realistic analysis. Zeihan certainly writes in a somewhat "loose" manner, with blunt assertions that seek to shake the reader, but his geopolitical axioms seem to be generally endorsed: if you boil down what he says in his three books, you have a clear notice of where the world is supposed to be going; and that is where it is indeed going.

[Richard Haas, The World. A Brief Introduction (New York, NY: Penguin Press, 2020), 378 p].

review / Salvador Sánchez Tapia

During a fishing workshop on Nantucket with a friend and his son, then a computer engineering student at the prestigious Stanford University, Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, engaged the young man in conversation about his programs of study, and asked him what subjects he had taken, apart from the strictly technical ones. To his surprise, Haass realised how limited issue of these he had taken were. No Economics, no history, no politics.

During a fishing workshop on Nantucket with a friend and his son, then a computer engineering student at the prestigious Stanford University, Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, engaged the young man in conversation about his programs of study, and asked him what subjects he had taken, apart from the strictly technical ones. To his surprise, Haass realised how limited issue of these he had taken were. No Economics, no history, no politics.

Richard Haass uses this anecdote, which he refers to in the introduction to The World. Education A Brief Introduction , to illustrate the general state of higher education in the United States - which is, we might add, not very different from that of other countries - and which can be summed up in this reality: many students in the country that has the best universities in the world, and which is also the most powerful and influential on the planet, which means that its interests are global, can finish their university-level training without a minimal knowledge - let alone understanding - of the world around them, and of its dynamics and workings.

The World. A Brief Introduction is a direct consequence of the author's concern about the seriousness of this important gap for a nation like the United States, and in today's world, where what he calls the "Las Vegas rule" - what happens in the country stays in the country - does not work, given the interconnectedness that results from an omnipresent globalisation that cannot be ignored.

The book is conceived as a basic guide intended to educate readers - hopefully including at least some of the plethora of uneducated students - of different backgrounds and levels of knowledge, on the basic issues and concepts commonly used in the field of International Office.

By the very nature of the work, informed readers should not expect to find in this book any great discoveries, revolutionary theories or novel approaches to contemplate the international order from a new perspective. Instead, what it offers is a systematic presentation of the essential concepts of this field of knowledge that straddles history, political science, sociology, law and geography.

The book avoids any theoretical approach. On the contrary, its goal is eminently practical, and its aim is none other than to present in an orderly and systematic way the information that the average reader needs to know about the world in order to form a criterion of how it works and how it is articulated. It is, in final, to make him or her more "globally educated".

From his vantage point as president of one of the world's leading global think-tanks, and with the experience gained from his years of service as part of the security establishment of the two Bush presidents, Richard Haass has made numerous important contributions to the field of International Office. In the case of the present book, the author's merit lies in the effort he has made to simplify the complexity inherent in International Office. In a simple and attractive prose, accessible to readers of all subject, Richard Haass, demonstrating a great understanding of each of the subjects he deals with, has managed to distil their essence and capture it in the twenty-six chapters of this brief compendium, each of which would justify, on its own, an enormous literary production.

Although each chapter can be read independently, the book is divided into four parts in which the author approaches status the current world and relations between states from different angles. In the first part, Haass introduces the minimum historical framework necessary to understand the configuration of the current international system, focusing in particular on the milestones of the Peace of Westphalia, the two World Wars, the Cold War, and the post-Cold War world.

The second part of the book devotes chapters to different regions of the world, which are briefly analysed from a geopolitical point of view. For each region, the book describes its status, and analyses the main challenges it faces, concluding with a look at its future. The chapter is comprehensive, although the regional division it employs for the analysis is somewhat questionable, and although it inexplicably omits any reference letter to the Arctic as a region with its own geopolitical identity and set to play a growing role in the globalised world to which the book constantly alludes.

The third part of the book is devoted to globalisation as a defining and inescapable phenomenon of the current era with an enormous impact on the stability of the international order. In several chapters, it reviews the multiple manifestations of globalisation - terrorism, nuclear proliferation, climate change, migration, cyberspace, health, international trade, monetary issues, and development- describing in each case its causes and consequences, as well as the options available at all levels to deal with them in a way that is favourable to the stability of the world order.

Finally, the last section deals with world order - the most basic concept in International Office- which it considers indispensable given that its absence translates into loss of life and resources, and threats to freedom and prosperity at the global level. Building on the idea that, at any historical moment, and at any level, forces that promote stable order operate alongside forces that tend towards chaos, the chapter looks at the main sources of stability, analysing their contribution to international order - or disorder - and concluding with what this means for the international era we live in. Aspects such as sovereignty, the balance of power, alliances and war are dealt with in the different chapters that comprise this fourth and final part.

Of particular interest to those who wish to delve deeper into these matters is the coda of the book, entitled Where to Go for More. This final chapter offers the reader a well-balanced and authoritative compendium of journalistic, digital and literary references whose frequent use, highly recommended, will undoubtedly contribute to the educational goal proposed by the author.

It is an informative book, written to improve the training of the American and, beyond that, the global public on issues related to the world order. This didactic nature does not, however, prevent Haass, at times, and despite his promise to provide independent, non-partisan criteria that will make the reader less manipulable, from tinginging these issues with his staff vision of the world order and how it should be, or from criticising - somewhat veiled, it must be said - the current occupant of the White House's international policy, which is not very globalist. Nevertheless, The World. A Brief Introduction offers a simple and complete introduction to the world of International Office, and is almost obligatory reading for anyone who wants to get started in the knowledge of the world order and the mechanisms that regulate it.