Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label chile .

Cyclical movements in the Latin American economy show close links to fluctuations in mineral pricing

The attention of public opinion on the price of commodities usually focuses on hydrocarbons, especially oil, because of the direct consequences on consumers. But although there are important oil producers in Latin America, minerals are a more transversal asset in the region's economy, especially in South America. This is shown by the largely parallel lines that follow the evolution of non-energy minerals and GDP growth, both in times of boom and of decline.

ARTICLE / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa [English version] [Spanish version].

Mining activity is a fundamental sector for most of the Latin American economies. The sector has a huge weight on exports and the attraction of foreign direct investment making it one of the most important sources of international currencies. Against the general perception of the non-energetic mining activities as a mature industry, the sector has demonstrated its capability to be attractive for investment and able to produce jobs and wealth. Latin American mining is the destiny of 30% of world investment in the sector, which is waiting for a rising in prices. The effect of these price fluctuations have direct consequences on the economies of the continent, some of them being deeply dependent on the exploitation and sell of its natural resources. The main goal of this analysis is to articulate a convincing explanation of the impact of price fluctuation on non-energetic minerals on national GDPs.

Firstly, it is important to explain the chronological evolution of prices in the most exploited minerals of Latin America. The general tendency of commodity prices during the last two decades has been marked by a great volatility. The so called super cycle of commodities [1] produced between 2003 and 2013, with recoil during 2008 and 2009, coincides with the golden decade of Latin America. This situation was produced thanks to an unprecedented rising of global demand, mainly of the emerging countries led by China. In fact, the rising of China has transformed the trade pattern in the region which is today the main trade partner of a large number of countries.

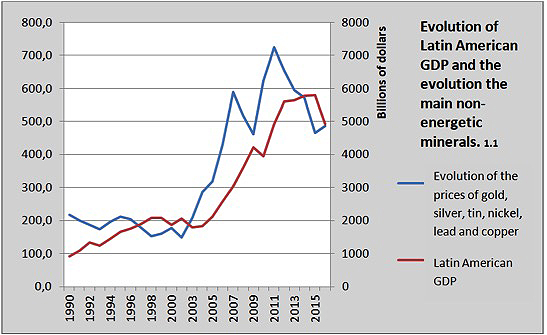

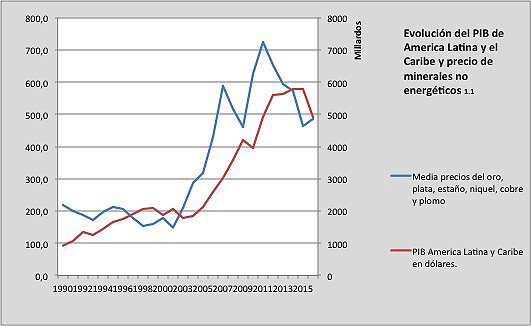

The mentioned evolution in commodity prices is similar to the one of the non-energetic minerals, which generally follows the tendencies of raw materials. As graph 1.1 shows, the region of Latin America and Caribbean has growth in correlation to the average evolution of the prices of gold, silver, tin, nickel, lead and copper. It is important to mention that this correlation in not an isolated one, and has to be analyzed in the context of a general rising in natural resource-based products such as hydrocarbons and agricultural goods.

|

[The graphics have been made from World Bank Data and national statistics of Peru and Chile]. |

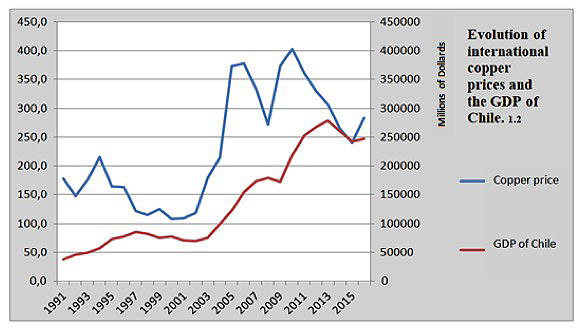

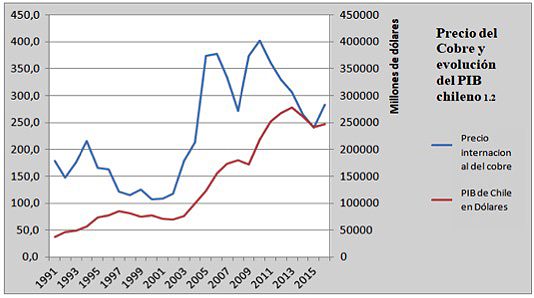

The Chilean case can be illustrative. The country has an economy particularly specialized on non-energetic minerals, outstanding copper as a core mineral for the country. Chile is the main producer of copper in the world and this mineral is around 50% of the national exports. The mining sector in Chile [2] represented 20% of the country's GDP during the 2000's, in 2017 it is only 9% of its economy. In graph 1.2 it is evident how the economic growth of Chile is directly linked with the different prices of copper. Even though it is one of the most complex and developed economies in the continent, with a tertiary sector [3] representing 74% of its GDP, Chilean economy is still dependent and affected by copper prices and the situation of the mining industry.

|

|

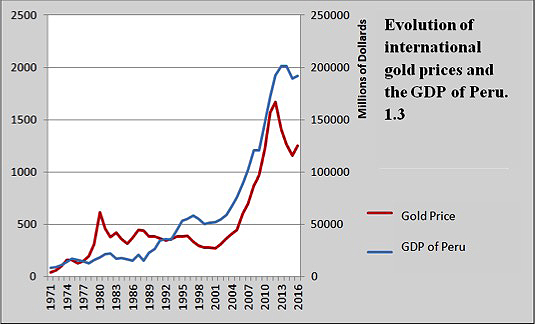

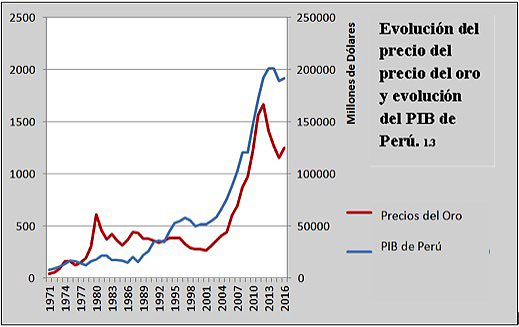

Another interesting case is the Peruvian one, a country whose exports are in a big proportion composed by non-energetic minerals. Gold is 18% and copper is 26% of all exports [4], reaching both more than 46% of them. Similar to the case of Chile, 15% of its national GDP comes from the mining activities. Again, the correlation of mineral prices and economic growth is evident in graph 1.3, showing the huge dependence of these economies to the international prices of their exports.

|

|

This relationship is logical and has its answer in different realities. On the one hand, the quantitative value of natural resources on the Latin American economies, whose exports are mainly composed by mineral, agricultural or energetic commodities. On the other hand, the qualitative importance of the mining sector, which creates huge amounts of employs (up to 9% of the total in Chile), is the activity of some of the main companies in the region (among the 20 biggest companies in the Latin America, 5 are related to the mining activities), it is the main source of currencies and support public budgets by its particular fiscal regime. Equally, a big amount of national public debts are covered by those particular taxes, creating a situation of possible default in case of great fluctuations of prices. This menace brings back the memories of the debt crisis in the 80's, something that it is now a reality in the case of Venezuela.

Must be taken into account that Latin American countries are not a unicity or a homogeneous reality, in general it is true that the region confronts a general challenge: be able of reduce the dependence of their economies to the exploitation and sell of its natural resources. An economic structure that is problematic because of its impact on the environment, a particularly complex issue because of the resistance of indigenous groups to suffer from it. The nature of the employs created by this activity is sometimes disappointing, with low wages and bad labor conditions. Anyway, the industrial development of the region is still far from being sufficient and there is a rising awareness about the lack of economic structural reforms during the golden decade of 2003-2013 that could have changed the situation [5]. The profits derived from the mining sector are used to promote political interest or short-term goals with electoral sights.

This inefficient use of the public resources increases the vulnerability of the general welfare to the mentioned continuous shifts in prices. Even though perspectives about prices are optimistic and expect an imminent rise [6], they will not reach the levels of 2008, when they were at their historical maximum. This new context will demand a new approach to Latin American economies, which will not have access to the huge amount of money that they had during the past decade. Its economic growth will not come from an external favorable context, but from internal efforts to modernize and renovate its economic capability.

The cycles of the Latin American Economics are closely linked to mineral prices: the graphs are astounding.

Public attention on the price of commodities is often focused on hydrocarbons, preferably oil, because of the direct consequences on consumers. But although Latin America has major crude oil producers, minerals are a more cross-cutting asset on the region's Economics , especially in South America. This is demonstrated by the largely parallel lines that follow the evolution of non-energy minerals and GDP growth, both in times of boom and bust.

article / Ignacio Urbasos Arbeloa [English version].

Mining is a fundamental activity for many Latin American economies. The sector has an enormous weight in exports and foreign investment, making it one of the main sources of foreign exchange. In contrast to the general perception of non-energy mining as a mature industry, the sector continues to be attractive to investors and is capable of continuing to generate employment and wealth. Latin American mining receives 30% of the world's investment in the sector, which expects a recovery in prices. The impact of these fluctuations has direct consequences on the economies of the continent, some of which are highly dependent on the exploitation and sale of these resources. The goal of this analysis is to articulate a convincing explanation of the Degree in which these price variations affect national GDPs.

First of all, it is important to detail the chronological evolution of prices of the main minerals exploited in Latin America. The general trend in commodity prices over the last two decades has been marked by enormous volatility. The so-called commodity super cycle [1] given approximately between 2003 and 2013, with a setback between 2008 and 2009, occurs at the same time as the so-called golden decade in Latin America. This status was produced by an unprecedented rise in world demand, thanks to emerging countries led by China, which has transformed foreign trade in the region, displacing the USA as the first partner of most of these countries.

The evolution in prices has followed a very similar patron saint in non-energy mining, which by rule generally follows the price trends of the rest of the raw materials. As we can see in Figure 1.1, the Latin American and Caribbean region has had an economic growth very similar to the average evolution of gold, silver, tin, nickel, lead and copper prices. It is important to mention that the relationship between these two variables is not isolated, and should be analyzed in the above-mentioned context of a general rise in the prices of other raw materials of vital importance for the region, such as hydrocarbons or agricultural products.

|

[The graphs are based on World Bank Data and national statistics from Peru and Chile] [The graphs are based on World Bank Data and national statistics from Peru and Chile]. |

The case of Chile can be extremely useful. Chile has a Economics particularly specialized in non-energy mining, highlighting the exploitation of copper, an activity in which it is a world leader and which accounts for 50% of its exports. The mining sector in Chile [2] reached almost 20% of GDP in the mid-2000s; in 2017 it has accounted for around 9%. In Figure 1.2 we see how the price of copper sets the country's economic path, with the greatest periods of Chilean economic growth coinciding with the increase in copper prices. Despite being one of the most developed economies in the region [3], with a 74% weight of the services sector in GDP, the country is still conditioned by the situation of its primary sector and specifically mining.

|

|

Another interesting case is Peru, a country whose exports include a good share of non-energy minerals [4], reaching 46% of exports in the case of gold (18%) and copper (26%). Similarly to Chile, the share of mining in the Economics is 15% of GDP. Again, we can appreciate the correlation between the prices of certain strategic non-energy minerals and economic growth.

|

|

This relationship is logical and responds to several realities. On the one hand, the great quantitative value of raw materials in Latin American economies, which concentrate their exports in agricultural, mineral and energy products. On the other hand, its qualitative importance since the sector generates large amounts of employment (up to 9% in Chile), is the object of many of the main companies in the region (5 of the 20 largest in Latin America are dedicated to extraction), is the main source of foreign currency and leaves enormous benefits for the coffers of the States, since they are governed under a particular tax system more burdensome. Likewise, a good part of the payment of foreign debt is covered by these revenues, and price instability could bring back the ghosts of the debt crisis of the eighties, something that is already a reality in the case of Venezuela.

Although the countries of Latin America cannot be analyzed as a heterogeneous unit, in general terms the region does face a common challenge : to be able to reduce the dependence of its economies on the exploitation and export of raw materials. An activity that has problematic elements such as its impact on the environment, a particularly complex issue in the region due to the reticence of indigenous groups, or the quality and stability of the employment they generate. In any case, the region's industrial development is still deficient and there are more and more voices warning that the golden decade of 2003-2013 was not used to make the necessary structural changes to mitigate this status [5].

The existence of complex realities partner-politics in Latin America has often led to the use of the benefits derived from extraction in short term and electoral policies, a scourge that increases the exhibition of social welfare to the ups and downs of the mining and energy sector. Although commodity price predictions point to an imminent recovery [6], status is not expected to be similar to the one around 2008 when prices reached historic highs. This new situation will demand the maximum from Latin American economies, which will not be able to count on such a favorable status from the international Economics .