Ruta de navegación

Menú de navegación

Blogs

Entries with label migration .

US agreements with the Northern Triangle may have had a deterrent effect before entering into force

In the first month following the extension of the Asylum Cooperation Agreements (ACA) to the three Northern Triangle countries, apprehensions at the US border have fallen below the levels of recent years. The actual reduction in migrant inflows that this evidences has to do with Mexico's increased control over its border with Guatemala, but may also be due to the deterrent effect of advertisement of the agreements, whose implementation has not yet fully begun and therefore has yet to demonstrate whether they will be directly effective.

![Honduran migrants held by Guatemalan border guards, October 2018 [Wikimedia Commons]. Honduran migrants held by Guatemalan border guards, October 2018 [Wikimedia Commons].](/documents/10174/16849987/tercer-pais-blog.jpg)

▲ Honduran migrants held by Guatemalan border guards, October 2018 [Wikimedia Commons].

article / María del Pilar Cazali

Attempts to entrance attempt to enter the United States through its border with Mexico have not only returned to the levels of the beginning of the year, before the number of migrants soared and each month set a new record high, reaching 144,116 apprehensions and inadmissions in May( USBorder Guard figures that provide an indirect assessment of migration trends), but have continued to fall to below several previous years.

In October (the first month of the US fiscal year 2020), there were 45,250 apprehensions and inadmissions at the US southern border, down from October 2018, 2015 and 2016 (but not 2017). This suggests that the total number of apprehensions and inadmissions in the new fiscal year will be well below the record of 977,509 recorded in 2019. This boom had to do with the caravans of migrants that began at the end of 2018 in the Central American Northern Triangle (Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala), following a migratory flow that, with different intensities, began in the 1980s due to political and economic instabilities in those countries.

This migration crisis led President Trump's US administration to implement tougher deportation policies, including changing conditions for expedited deportations. In addition, the White House pressured Mexico with the threat of tariffs on its products if it did not help reduce the flow of migrants crossing Mexican soil, prompting President López Obrador to deploy the newly created National Guard to the border with Guatemala. Trump combined these measures with the negotiation of Asylum Cooperation Agreements (ACAs) with the Northern Triangle countries, which were initially improperly referred to as "safe third countries", adding to the controversy they generated.

agreement with Guatemala

Due to US threats to impose tariffs on Guatemala if it failed to reduce the issue of migrants from or through Guatemala on their way to the US, the Guatemalan government accepted the terms of a attention announced by Trump on 26 July 2019. The agreement foresees that those who apply for asylum in the US but have previously passed through Guatemala will be brought back to the US so that they can remain there as asylum seekers if they qualify. The US sees this as a safe third country agreement .

A safe third countryagreement is an international mechanism that makes it possible to host in one country those seeking asylum in another. The agreement signed in July prevents asylum seekers from receiving US protection if they passed through Guatemala and did not first apply for asylum there. The US goal is intended to prevent migrants from Honduras and El Salvador from seeking asylum in the US. Responsibility for processing protection claims will fall to Washington in only three cases: unaccompanied minors, persons with a US-issued visa or document Admissions Office , or persons who are not required to obtain a visa. Those who do not comply with requirements will be sent to Guatemala to await the resolution of their case, which could take years. On the other hand, the agreement does not prevent Guatemalan and Mexican applicants from seeking asylum in the US.

Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales had previously announced that a similar agreement could become part of the migration negotiations with the US. In Guatemala, after advertisement of what had been agreed, multiple criticisms arose, because the security conditions in both countries are incomparable. This was compounded by rumours about the true content of the agreement that Morales had signed, as it was not immediately revealed to the public. Faced with this uncertainty, Interior Minister Enrique Degenhart declared that the agreement was only for Hondurans and Salvadorans, not for nationals of other Latin American countries, and that the text did not explicitly mention the term "safe third country".

In the week following the advertisement, three appeals for amparo against the agreement were lodged with Guatemala's Constitutional Court, arguing that the country is not in a position to provide the protection it supposedly offers and that the resulting expense would undermine the economic status of the population itself. However, Degenhart defended agreement by saying that the economic repercussions would have been worse if the pact with Washington had not been reached, because with the US tariffs, half of Guatemala's exports and the jobs that accompany these sectors would be at risk.

These criticisms came not only from Guatemalan citizens, but also from public figures such as Guatemala's Human Rights Ombudsman, Jordán Rodas, citing a lack of transparency on the part of the government. Rodas insisted that Guatemala is not fit to be a safe third country because of its low indicators of production, Education, public health and security. Similar ideas have also been expressed by organisations such as Amnesty International, for whom Guatemala is not safe and cannot be considered a safe haven.

In its pronouncement, Guatemala's Constitutional Court affirmed that the Guatemalan government needs to submit the agreement to congress for it to become effective. This has been rejected by the government, which considers that international policy is skill directly the responsibility of the country's president and will therefore begin to implement what has been decided with Washington without further delay.

![Apprehensions and inadmissibilities by US Border Guard, broken down by month over the last fiscal years (FY) [Taken from CBP]. Apprehensions and inadmissibilities by US Border Guard, broken down by month over the last fiscal years (FY) [Taken from CBP].](/documents/10174/16849987/tercer-pais-grafico.png)

Apprehensions and inadmissibilities by US Border Guard, broken down by month over the last fiscal years (FY) [Taken from CBP].

Also with El Salvador and Honduras

Despite all the controversy generated since July as a result of the pact with Guatemala, the US developed similar efforts with El Salvador and Honduras. On 20 September 2019, El Salvador's president, Nayib Bukele, signed a agreement similar to the safe third country figure, although it was not explicitly called that either. It commits El Salvador to receive asylum seekers who cannot yet enter the US, similar to the agreement with Guatemala. El Salvador's agreement has the same three assumptions in which the US will have to make position of migrant protection.

The Salvadoran government has received similar criticism, including a lack of transparency in the negotiation and denial of the reality that the country is unsafe. Bukele justified signature by saying it would mean the extension of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for the more than 190,000 Salvadorans living in the US. In October 2019, the Salvadoran Foreign Ministry said that this agreement is not a safe third country because El Salvador is not in the serious migratory situations in which Guatemala and Honduras are in terms of the flow of people, so it is only a agreement of non-violation of rights to minimise the number of migrants.

On 21 September 2019 the Honduran government also made public the advertisement of a agreement very similar to the one accepted by its two neighbours. It states that the US will be able to deport to Honduras asylum seekers who have passed through Honduras. Like the other two countries, the Honduran government was criticised as not being a safe destination for migrants as it is one of the countries with fees highest homicide rates in the world.

Despite criticism of the three agreements, in late October 2019 the Trump administration announced that it was in final preparations to begin sending asylum seekers to Guatemala. However, by the end of November, no non-Guatemalan asylum seekers had yet been sent. The inauguration in early January of President-elect Alejandro Giammattei, who announced his desire to rescind certain terms of agreement, may introduce some variation, though perhaps his purpose will be to wring some more concessions from Trump, in addition to the agricultural visas that Morales negotiated for Guatemalan seasonal workers.

The avalanche of unaccompanied foreign minors suffered by the Obama Administration in 2014 has been overcome in 2019 with a new migratory peak

In the summer of 2014, the United States suffered a migration crisis due to an unexpected increase in the number of people in the country. issue of unaccompanied foreign minors, mostly Central Americans, who arrived at its border with Mexico. What has happened since then? Although oscillating, the volume of this subject Immigration prices fell, but in 2019 a new record has been recorded, hand in hand with the "caravan crisis", which has led to the rise again in total apprehensions at the border.

![U.S. border agents search unaccompanied minors at Texas-Mexico border in 2014 [Hector Silva, USCBP–Wikimedia Commons] U.S. border agents search unaccompanied minors at Texas-Mexico border in 2014 [Hector Silva, USCBP–Wikimedia Commons]](/documents/10174/16849987/migracion-blog.jpg)

▲ U.S. border agents search unaccompanied minors at Texas-Mexico border in 2014 [Hector Silva, USCBP–Wikimedia Commons]

article/ Marcelina Kropiwnicka

The United States hosts more immigrants than any other country in the world, with more than a million people arriving each year, either as legal permanent residents, asylum seekers and refugees, or in other immigration categories. While there is no exact figure for how many people cross the border illegally, U.S. Customs and Border Control (U.S. Customs and Border Control) measures changes in illegal immigration based on the number of apprehensions made at the border; Such arrests serve as an indicator of the issue total number of attempts to enter the country illegally. As for the data, it can be concluded that there have been notable changes in the demographics of illegal migration at the border with Mexico (southwest border, in official U.S. terms) in recent years.

The peak of apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border was during 2000, when 1.64 million people were apprehended trying to enter the United States illegally. The numbers have declined, across the board, since then. In recent years, there have been more apprehensions of non-Mexicans than Mexicans at the border with the neighboring country, reflecting a decrease in issue of unauthorized Mexican immigrants who came to the U.S. in the last decade. The increase, in fact, was largely due to those fleeing violence, gang activity and poverty in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, a region known as Central America's Northern Triangle.

The nations included in the Northern Triangle are among the poorest in Latin America – a high percentage of the population still lives on less than $2 a day (the international poverty line is $1.90); There has been little progress in reducing poverty in recent years. Within Latin America and the Caribbean, Honduras has the second highest percentage of the population living below the poverty line (17%), after Haiti, according to the latest data of the World Bank.

Unaccompanied Alien Minors

While fewer unaccompanied adults have attempted to cross the border without authorization over the past decade, there has instead been a surge of unaccompanied alien minors (MENAs) trying to enter the United States from Mexico. The migration of minors without accompanying adults is not new; What is new now is its volume and the need to implement policies in response to this problem. The increase in apprehensions of MENAs in FY2014 caused alarm and prompted both intense media scrutiny and the implementation of policy responses; Attention was maintained even as the phenomenon declined. The numbers dropped again to just under 40,000 apprehensions of minors the following year.

The international community defines an unaccompanied migrant minor as a person, "who is under eighteen years of age" and who is "separated from both parents and is not being cared for by an adult who by law or custom has the responsibility to do so." Many of these unaccompanied minors report immediately to U.S. border security, while others enter the country unnoticed and undocumented. Not only this, but children have no parents or legal guardians available to provide care or physical custody, which quickly overwhelms the services of local border patrols.

In 2014, many of the unaccompanied children said they were under the false impression that the Obama administration was granting "permits" to children who had relatives in the U.S., as long as they arrived no later than June. These false convictions and hoaxes were even more potent this past year, especially as President Trump continues to reinforce the idea of restricting migrants' access to the United States. The cartels have continued to transport a issue increasing number of Central American migrants from their countries to the United States.

Critical moments of 2014 and 2019

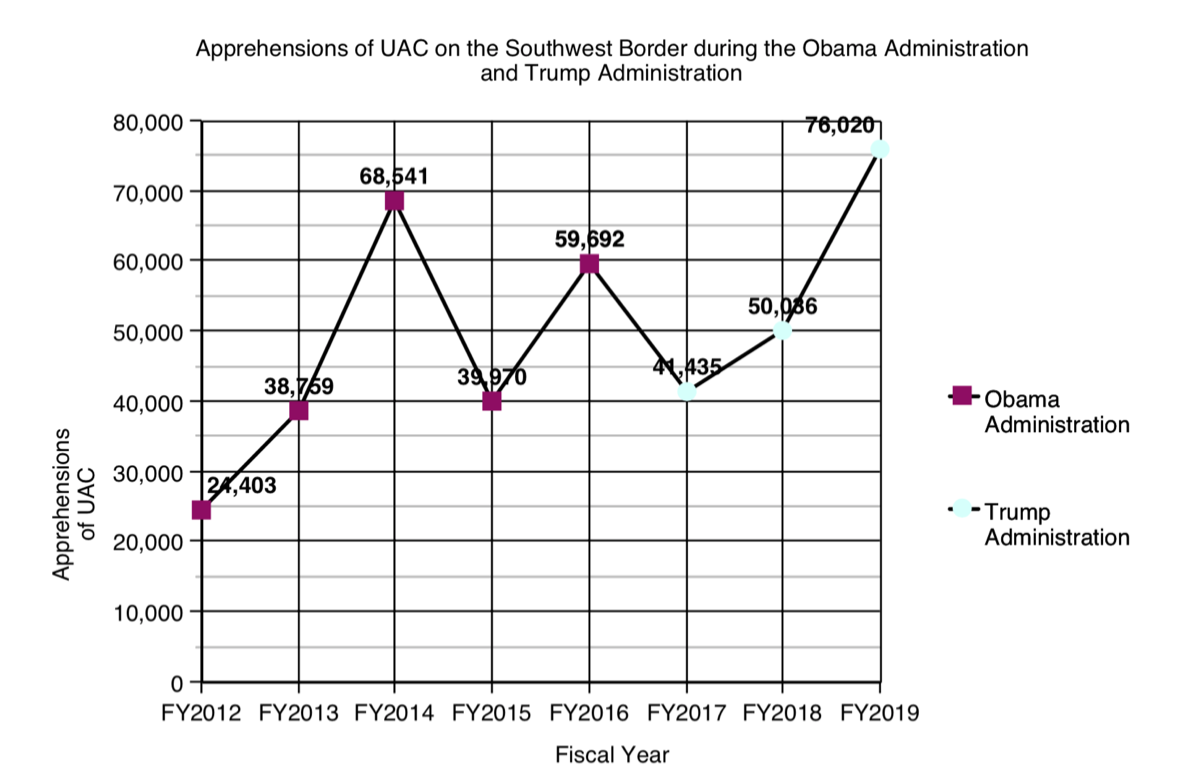

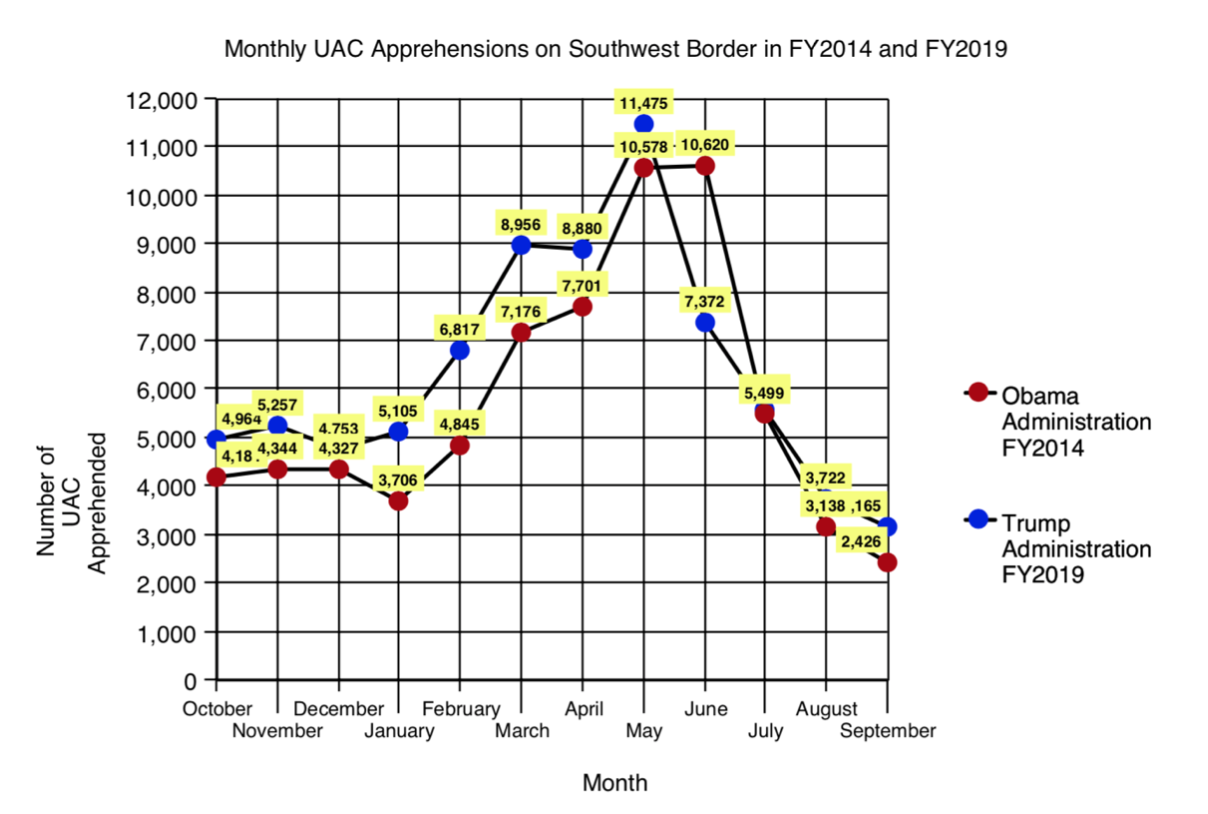

In 2014, during Obama's second term, total apprehensions along the border with Mexico reached 569,237 (this figure includes "inadmissible" people), a record only surpassed now. While the increase over the previous year was 13%, the increase was much more B regarding the arrests of MENAs; These rose from 38,759 in fiscal year 2013 to 68,541 in fiscal year 2014 (in the U.S. the fiscal year runs from October of one year to September of the next), an increase of almost 80%, more than four times those recorded in fiscal year 2011. In the case of minors from Honduras, the figure rose from 6,747 to 18,244 in one year; those of Guatemala rose from 8,068 to 17,057, and those of El Salvador, from 5,990 to 16,404 (those of Mexico, on the other hand, fell from 17,240 to 15,634). The Greatest issue The number of apprehensions occurred in May, a month in which MENA arrests accounted for 17% of total apprehensions.

Since 2014, apprehensions of unaccompanied minors, while fluctuating, have declined by issue. But in 2019 a new record has been recorded, reaching 76,020, with a maximum in the month of May. However, that month they accounted for only 9% of the total apprehensions, because this time it has not been a MENA crisis, but has been inserted into a B peak of total apprehensions. While overall apprehensions decreased significantly during the first six months of Trump's presidency, they then rose, reaching a total of 851,508 in 2019 (with the "inadmissible" the figure reached 977,509), which is more than double the number from 2018. The issue total apprehensions increased by 72% from 2014 to 2019 (in the case of MENAs the increase was 11%).

|

|

Apprehensions of unaccompanied alien minors at the U.S.-Mexico border, between 2012 and 2019 (Figure 1), and comparison of 2014 and 2019 by month (Figure 2). source: US Customs and Border Patrol.

Reaction

The U.S. had a variety of domestic policies aimed at dealing with the massive increase in immigration. However, with the overwhelming peak of 2014, Obama called for funding for a program for "the repatriation and reintegration of migrants to the countries of Central America and to address the root causes of migration from these countries." Although funding for the program has been fairly consistent over the past few years, the budget for 2018 proposed by the President Trump reduced the financial aid to these countries by approximately 30%.

The Trump Administration has made progress in implementing its diary on immigration, from the beginning of the construction of the wall on the border with Mexico to the implementation of new programs, but the hard line already promised by Trump in his degree program The U.S. government has proven ineffective in preventing thousands of Central American families from crossing the southwest border into the United States. With extreme gang violence running rampant and technicalities in the U.S. immigration system, migrants' motivation to leave their countries will remain.

▲ U.S.-Mexico border at Anapra, outside Ciudad Juárez [Dicklyon].

ANALYSIS / Túlio Dias de Assis and Elena López-Doriga

With a vote of 152 countries in favor, five against and twelve abstentions (1), the United Nations General Assembly approved last December 19 the project resolution ratifying the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, agreement signed a few days earlier in the Moroccan city of Marrakech. This is the first international pact, under the auspices of the UN, aimed at addressing migration at the global level. While it is not a binding agreement , it is intended to reiterate important principles on the protection of the human rights of migrants in a universal and unified manner, as it is implemented by the UN General Assembly.

Despite the positive aspect of reaching a broad consensus, many countries abstained from voting or positioned themselves directly against the pact, generating uncertainty as to its effectiveness. Although the long-awaited signature was eventually carried out in Marrakech, in the end there were far fewer signatories than expected during the negotiations. Why this rejection by some countries? And the neutrality or indifference of others? Why the multiple debates that have taken place in various parliamentary chambers around the world in relation to the pact? These are some of the questions that will be addressed in this analysis.

Before addressing the covenant itself, it is important to differentiate between the concepts of "migrant" and "refugee". A migrant is defined as a person who arrives in a country or region other than his or her place of origin to settle there temporarily or permanently, often for economic reasons and generally with the goal aim of improving his or her standard of living. While the concept of refugee makes reference letter to people fleeing armed conflict, violence or persecution and are therefore forced to leave their home country to ensure their own safety. The reasons for persecution can be of many different types: ethnic, religious, gender, sexual orientation, among others. In all of them, these causes have given rise to well-founded fears for their lives, which, after due process, make them "refugees" in the eyes of the international community.

It should be noted that this covenant deals only with the rights of migrants, since for refugees there is already the binding historical reference of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 amendmentprotocol , both signed and ratified by a large majority of UN member states. In addition, it should be mentioned that, simultaneously with the elaboration of the migration pact, a similar non-binding pact on refugee issues was also drawn up. This pact was supported by a large majority of States, with only two votes against (USA and Hungary) and three abstentions (Dominican Republic, Libya and Eritrea). Therefore, it could be concluded that at least in subject of refugees most countries do not seem to have any problem; as far as migrants are concerned, the opinion seems to change quite a lot.

The origins of the text date back to the 2016 New York Declaration on the Rights of Migrants and Refugees, which proposed the elaboration of both covenants - on the one hand the one concerning refugees, and on the other hand, the one on migration - as a further initiative of the implementation of the diary 2030. Since then, both documents were gradually elaborated until the text of the one that concerns us was finalized in July 2018.

The document, of a non-binding nature, consists of several parts. The first, commonly referred to as the "Chapeau", is simply a statement of shared values that all States in the international community are supposed to possess. It is followed by a list of 23 objectives, mainly at subject of international cooperation, largely through the International Organization for Migration (IOM), a subsidiary body of the United Nations. Finally, the text explains how the periodic review of the progress of the signatory States with regard to the 23 objectives is to be carried out.

The most controversial part throughout and after the negotiations is the Chapeau, especially for equating the rights of migrants and refugees. The document as a whole is also criticized for not clearly distinguishing the rights of regular migrants from those of irregular migrants. Finally, another highly controversial measure was the call for signatory countries to facilitate a greater issue of visas.

Other important points of the text attracted substantial support agreement, although they were not spared the criticism of the more conservative governments: among them the guarantee of good conditions and care for migrants in cases of deportation, the principle of non-refoulement applied to migrant deportations (the non-refoulement of migrants to conflict zones), the granting of social rights to migrants in the countries where they are, the creation of a better network of international cooperation in subject of migrants under the administration of the IOM, as well as the creation of measures to combat discrimination against migrants.

DIFFERENT POSITIONS

In America

During the negotiations only two countries explicitly showed an aversion to treaty-making. Sharing the position of Orbán's Hungary was Trump's USA, which did not even bother to participate in the negotiations. The then US ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, took a strong stand against the agreement. "The U.S. prides itself on its migratory origins, but it will be the Americans themselves who will decide how to control their borders and who can enter," Haley declared, emphasizing the U.S. interest in making its national sovereignty prevail. The US ended up not signing the document.

In addition to the reasons provided by the Trump Administration, the loss of IOM leadership by the US to Portugal's António Vitorino candidate - and thus the loss of control over the implementation of the pact - may also have played a role. Perhaps not so much in the primary decision not to participate in the negotiations of the pact, as in the final attitude of not signing it. Likewise, it is striking that several countries that at first seemed to support the pact ended up withdrawing, as in the case of Brazil after Jair Bolsonaro's inauguration, or not signing, such as Chile or the Dominican Republic, which had not initially opposed the proposal. This lack of adhesion would be justified, according to some of the negotiators, by the persuasion attempts of US diplomats, although this US effort does not seem to have been limited to the Latin American sphere. Similarly, it is worth mentioning that the decision of the Dominican delegation was also largely influenced by internal pressures from some groups in the legislature.

In Europe

"Hungary could never accept such a partisan, biased and pro-migration document. Migration is a dangerous phenomenon". So began the speech of Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjaártó during the celebration of the end of the pact negotiations on July 13. Hungary, together with the USA, was one of the few countries that opposed the proposal from the beginning, but the Magyar representation, in contrast to the US, did take part in the negotiations. The fact that the Magyar representation took such a different position from the outset compared to the other EU member states meant that the seat assigned to the European diplomatic corps was empty during the entire negotiations.

However, Hungary was not the only European country to take such a radical position on agreement. It is worth noting that, once the negotiations were over, along with Hungary there were four other countries in the General Assembly opposed to the pact: Poland, the USA, the Czech Republic and Israel. In addition, twelve more abstained, including several EU members, such as Austria, Bulgaria, Italy, Latvia and Romania, while Slovakia absented itself from the vote.

In several of these countries there was a bitter parliamentary discussion . In Belgium, which eventually accepted the text, Prime Minister Charles Michel lost his coalition government for having signed the pact, as the New Flemish Alliance, his main ally in the Executive, refused to ratify the document. In the Bundestag there was also some controversy caused by Alternative für Deutschland and some CDU members, although the adoption was finally approved after a vote in which a majority of 372 in favor, against 153 votes against and 141 abstentions, ended up approving the measure. In Latvia, the Riga parliament clearly rejected the agreement, as did the governments of Bulgaria, Austria, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Italy and Switzerland did not accept the pact at first, but the Executives of both states have referred the decision to their respective parliaments for final say. In the rest of Europe, the pact was accepted without major problems, despite the fact that in almost all national parliaments, far-right or right-wing conservative parliamentary groups raised objections.

China, Russia and others

The positions of other countries should also be highlighted. Australia was the first to withdraw its support for the pact after the negotiations; it justified its exit by stating that its current system of border protection is totally incompatible with some parts of the pact, a security invocation also used by Israel. China and Russia ended up signing the pact, but reiterated their refusal to comply with several of the objectives. Finally, practically all the countries of Africa and the Middle East supported the initiative, without raising any particular resistance, probably due to the fact that these are regions where the most significant migratory flows originate.

BAD FOR THE EU AND FOR THE UN

At final, the difficulty of a global migration pact lies in the concern with which many migrant-receiving countries view these movements of people. The reluctance of European countries is largely due to the migratory crisis in the Mediterranean, caused by the various conflicts in the Maghreb and the Middle East; in the case of the United States, it would be motivated by the migratory flows to its border with Mexico from Central and South America. In general, all the countries that resisted the adoption of agreement have in recent years been destination points for massive immigration, against which they have established strict border controls; in these societies the civil service examination to such an open-minded proposal as the one promoted by the United Nations, despite not being binding, has been seen as normal.

On the European scene, the different positions taken by the EU member states could be a bad sign for European integration, as once again the European External Action Service seems to have failed to create a common position for the EU. The fact that European representation was not present from the outset, due to Hungary's initial unwillingness to change its position, calls into question the common diplomatic service. Moreover, the initial common position that the other 27 EU states seemed to have, apart from the Magyar position, completely vanished at the end of the process, as several of them ended up dissociating themselves from agreement. This marked a clear division within the EU on migration, an issue on which there are already quite a few open debates in the European institutions.

In general, despite the large issue of signatory countries, taking into account all the civil service examination created and the political crises that occurred in some countries, the initiative on migration could be classified as of doubtful effectiveness, and in some aspects even as a failure on the part of the UN. It is evident that the United Nations seems to have lost some of its ability to promote its global diary , as it used to do until a decade ago. Probably ten years ago, the West would have unanimously accepted the migration proposals of University Secretary; today, however, there is a greater division among Western countries, as well as within their own societies, among which there is skepticism towards the organization itself.

After all, it is clear that among the countries that have opposed a global migration pact, a certain alignment against the idealistic approach is beginning to be noticed at International Office, while at the same time we see an enhancement of the attitude known as realist: just look at Trump's USA, Salvini's Italy, Orbán's Hungary, Bolsonaro's Brazil and Netanyahu's Israel, to cite the most emblematic cases.

In the future, the UN will probably have to adapt its projects to the new international political reality if it hopes to maintain its influence among its member states. Will the UN be able to adapt to this new wave of realist conservatism? Undoubtedly, interesting times await us for the next decade on the international scene...

(1) Against: Czech Republic, Hungary, Israel, Poland, Poland, United States. Abstaining: Algeria, Australia, Austria, Bulgaria, Chile, Chile, Italy, Latvia, Libya, Liechtenstein, Romania, Singapore and Switzerland.